Human Resource Management in Nonprofit Organizations

Overview

This chapter outlines theories and practice of staff management that are relevant to nonprofit organizations. It examines the use of management skills, including teamwork and coaching, recruitment, motivating and supporting directors, staff, volunteers to build a cohesive approach and progress as a nonprofit organization.

If you go into any newsagents, you will see an endless supply of management books, recommending different solutions or styles. This illustrates the constantly changing fashions in management, in the same way Human Resources (HR) is sometimes now called Talent Management and previously was called Personnel Management. I will stick with HR and try to pick out the wheat from the chaff to produce something of value.

Charles Handy (Handy 1993) suggests there are over 60 different variables which influence good staff management, including staff skills, motivation, relationships, and structures. He suggests that “selective focusing…or… ‘Reductionism’…will not do for the manager who has to put the lot together and make it work: beware the manager who hawks one patent cure.”

Managing in the nonprofit sector is very different from managing in the private sector. As Peter Drucker (Drucker 1990) wrote that “CVOs (Community and Voluntary Organizations) have to deal with a greater variety of stakeholders and constituencies than the average business.” He noted that one of the basic differences between for-profit and nonprofit sectors is that “CVOs (Community and Voluntary Organizations) always have a multitude of constituencies…There have always been a multitude of groups, each with a veto power.”

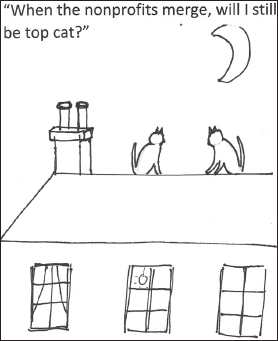

The primary task of a nonprofit organization is not just about breaking even financially, but meeting social objectives, which then overlay and affect any financial objectives. Many nonprofit organizations cannot move forward far or fast enough together in the same direction, because not all staff and directors agree on the same objectives. In addition mergers between organizations can lead to problems, let alone any resulting changes in staff conditions of service. These can affect staff motivation in major ways, as can fear about losing jobs.

Many nonprofit organizations struggle continually to generate sufficient funds and income, which can require changes in service delivery and staffing, sometimes at short notice. In turn this places pressures on managers, who must understand teamwork and other HR and management skills, such as change management (see Chapter 8).

People management is not an exact science, research into how people behave can produce inexact results, “entrepreneurship is a young…research field” (Landström 2007). Numerous different management theories are propagated by self-help gurus, which can just confuse the average manager. In this role, you are dealing with peoples’ livelihoods and aspirations, working with their personalities and your own, trying to harness a team composed of people from diverse backgrounds to work well together, toward the organization’s own objectives. All these make management demanding.

Societal Changes

Several changes in particular have taken place over the last 20 years that have had a profound effect on staff management; first we have become a much more litigious society (Furedi 2012): as a result there are increasing obligations and responsibilities (both legal and nonlegal) on recruitment and treating staff fairly; this has been reinforced by increased litigation through employment tribunals and resulting publicity; second it is now accepted that the “command and control style of management are not going to work anymore” (Clarke 2013) and staff, particularly those from younger generations, expect and “like consensus and collaboration.”

Nonprofit organization managers may also become caught in a values trap. Their commitment to better employment rights and conditions for workers means that they have tended to avoid some of the tougher HR practices of their commercial counterparts, such as competence testing, zero hours contracts, and performance-related pay. In some cases this commitment leaves them vulnerable to being exploited by those few staff who in reality lack the competences to do their jobs. Managers need to be objective about their staff’s (and their own) performance and act accordingly in the best interests of the organization.

Another change is that all companies are now held to account by the public and media for any bad or antisocial avoidance behavior; an example being the way that Starbucks sales have gone down since being accused of tax avoidance, while Google’s brand has been damaged by its tax according to newspaper reports (Daily Telegraph 2013), and charity behavior has also been under close scrutiny particularly with regard to issues such as fundraising and the pay of senior staff.1 Another factor is the growth in the importance of diversity and equality issues, as the UK’s population has become more multicultural and people require greater gender equality. A further change has been the growth of service user involvement in nonprofit organizations, including at Board level. Some, such as St Mungos, also have a policy of recruiting more former service users as staff, initially as apprentices (St Mungos 2015). In addition most nonprofits have significant service user involvement, at many different levels, including board level.

Staffing is invariably both your biggest cost and your greatest headache, unfortunately with no easy solutions. Large organizations will have HR departments that carry out most of the work required and should provide a degree of objectivity. Small organizations invariably do not have a specialist HR department, which means that managers have to carry out some or even all the HR work. However it is absolutely essential that organizations follow both good practice and the law, even though the amount of employment-related legislation and regulation has increased substantially over the last two decades.

Some desk-based research carried out a few years ago found that even small UK community organizations may be subject to over 1,500 separate pieces of legislation and regulation, around half of which was employment related (Community Matters 2009) and since then pensions have been expanded. However HR information, polices, and forms can all be easily bought online from private companies and a very useful U.S. resource is Guidestar2 while in the UK the NCVO specializes in support for nonprofits.3 One big advantage of these online resources is that they are invariably free, their information is written by HR professionals and they are updated regularly to take account of any new legal requirements.

There are also private online HR companies, supplying up-to-date information and polices, customized to your organization for a fee. These may be the best solution to ease the work load on managers of small organizations.

One of the keys to successful management in all sectors is getting the right team to work with you in the organization. Jim Collins has elaborated on this aspect in his books on companies and the Voluntary and Community Sector (Collins 2006); he writes “Those who build great organizations make sure they have the right people on the bus, the wrong people off the bus and the right people in the key seats before they figure out where to drive the bus.” In other words the best managers select the right team, then involve the team in planning the project; the overall concept and direction may already have been decided but getting the team involved in the planning ensures a greater span of ideas, empowers the individual team members and gains their commitment to the project.

The Recruitment Process

Before staff are recruited, the manager must prepare a range of papers and processes. Organizations must be aware they have a legal responsibility to ensure no unlawful discrimination occurs in recruitment and selection on the grounds of sex, race, disability, age, sexual orientation and religion or belief, pregnancy, maternity, marriage and civil partnership, and gender reassignment. If the process is unfair then this can be grounds for legal action, so you must get it right; staff selection is subject to government regulation and legislation, eleven acts or regulations in the UK.

The recruitment process should cover:

• Defining the service you need, analyzing the job, the salary, and the necessary skills and experience required.

• Preparing a job description and person specification.

• Advertising vacancies.

• Interviewing, selecting and hiring staff.

• Inducting the new staff into their role and supervising their probationary periods.

A business start-up service (Shell Livewire Business Library4) states:

Recruitment and selection can be seen as a two-stage process: Recruitment attracts the optimum number of suitably qualified candidates to apply for the post; and, selection filters this potentially large group through a variety of criteria in order to determine their suitability to match the needs of the job and the business. Recruitment and selection must be considered as two separate processes, otherwise one or both may fail. If you filter wrongly at recruitment, you may end up with a pool of poor candidates. If you attract wrongly at selection, you may end up with a poor fit between the job and the job-holder.

Job Descriptions and Person Specifications

It is essential to think through exactly what the staff role will entail; job design should produce an appropriate description of the skills and competences, knowledge and experience required for different posts. The job description outlines the tasks and responsibilities required for the role. The person specification, which should cover the tasks and responsibilities in the job description, should be an objective document, outlining the competences, knowledge, attitudes, and experience required for the role. These are normally separated out into essential and desirable attributes, which can then be used for scoring on each attribute but it can also be useful as a document to enable potential candidates to consider their own suitability and to make their application relevant to what is required.

Advertising will be important though most jobs in the economy are filled by word of mouth and internal promotion. Often there are candidates within the organization who are ready to take the next step. Networking and putting jobs onto bulletin boards and LinkedIn can spread the recruitment net wider.

Selection

Selecting and recruiting the right team needs to be rigorous and thorough, but in reality it is still a very difficult process; one experienced manager once said that the chances of selecting the right candidate at formal interviews was like sticking a pin in list of names; so probationary periods are essential (see the following). Some managers believe in offering short-term contracts to assess the standard of candidates more thoroughly. It becomes more difficult when selection boards disagree among themselves; even if they are meant to be applying objective criteria, subjectivity invariably creeps in.

The selection process should use a variety of methods, including tests, interviews, mock exercises, and meeting clients or service users. No post should be offered before taking up references and some managers always try to talk to referees over the phone to get nuances about people’ performance. One useful maxim is “if in doubt do not appoint.”

Recruiting Volunteers

With volunteers the process must be similar but different; job descriptions and specifications should be drawn up but clearly there is more risk of volunteers staying only a short time and the effort of recruitment being wasted. Advice and guidance is available from national nonprofit support organizations in the U.S.5 and UK,6 while regional and local networks often provide useful resources or help recruit and support in the UK7 or U.S.8 There is also a UK Quality Mark specifically for employing volunteers.9

Probation and Induction

In addition the process of “getting the right people on the bus” will need to include stringent use of probationary periods to test out whether staff are suitable for their roles, normally over the first 6 months. Another way is offering short-term contracts to test out suitability, or going through agencies for temporary to permanent contracts.

Induction is also important, particularly if you are recruiting young inexperienced staff. One manager always used to state it was better to recruit inexperienced people with great potential and then train them up to the right methods and standards for their organization.

Staff Handbook

At an early stage it is essential to write up a staff handbook for the organization, outlining staff hours, conditions of service, pension, collective bargaining, employment contracts, disciplinary procedures, employee involvement, equal opportunity and diversity, flexible working, grievance procedures, health and safety, holidays and time off, job sharing, pay, pensions, grading, and notice periods. There are templates which can be adapted.10,11 This can be changed as conditions and organizations change, so it is sensible to print any hard copies as loose leaf binders so updates can be inserted.

If your organization is involved in construction or maintenance work, or risky work, you will need a comprehensive health and safety manual, with additional training for staff and trainees. Likewise this is needed if your organization provides services that place staff or service users at risk in any way such as hostels or outreach work, or where you are working with risky clients.

Staff Participation

Charles Handy (Handy 2006), a perceptive writer on organizational management, believed “It is only common sense that people are more likely to be committed to a cause if they have had a hand in shaping it” and that “Groups are likely to produce better result than the same individuals working on their own, though teams of all-stars are not always or even often the best teams. The egos get in the way of the sharing.”

In fact engagement, empowerment, or participation must also include engagement with consumers and service users, (dealt with in Equal Opportunities chapter). The nonprofit sector has a great deal of experience in this whole area. However sometimes never-ending consultations seem to stymie any real action leading to unsatisfactory compromise, but this is often a sign of opposition to change from vested interests within an organization. This may be because the right steps have not been followed.

Staff Motivation

Motivating staff is absolutely key but there are no simple, sure fire solutions, but managers should always be working on this as it is clear that motivated staff produce better performance. Managers talk about different ways to motivate different staff; one way is getting to know individual staff and then applying “different strokes for different folks” or utilizing situational leadership (see Managing Resources chapter), allowing experienced and independent staff more scope than newer less experienced staff. Another tactic is the “feedback sandwich,” that is when you need to correct or be critical of someone’s behavior or performance, you also find something to praise about their work.

It is essential to set up a culture where staff are encouraged to contribute ideas, as they often have the best perspective about where the organization should be going and how best to improve results. Team meetings are a good strategy (see Managing Resources chapter).

Motivation

One big motivating factor can be the competitiveness of staff; according to Professor Ian Larkin (Larkin 2012), staff’s natural tendency is to measure their own performance against the performance of others. This is both within a team and against competing organizations.

Organizations should pay the going rate to recruit good staff and then to retain them as they become more experienced. Pay rates must be fair and transparent, so the structure and rationale can be explained if challenged. But as I say in the Business Planning chapter, the staff pay structure should also be closely linked to performance, both of individual staff and of the company as a whole, rather than just recruiting staff on salaries with automatic increments.

Most staff in nonprofit organizations are altruistic, wanting to help society in some way or other. Research on public service (Ashraf, Bandiera and Jack 2014) found that

First, non-financial rewards are more effective at eliciting effort than either financial rewards or the volunteer contract, and are also the most cost-effective...... Second, non-financial rewards leverage intrinsic motivation and, contrary to existing laboratory evidence, financial incentives do not appear to crowd it out.….. Overall, the findings demonstrate the power of non-financial rewards to motivate agents in settings where there are limits to the use of financial incentives.

Staff Learning

Peter Drucker (Drucker 1990) argues that “CVOs (Community and Voluntary Organizations) need to be learning organizations… to be information based…structured around information that flows up from the individuals doing the work to the people at the top and on around information flowing down too.” The flow of information is essential because a CVO has to be a learning organization. People throughout the CVO need to ask: “What do I have to learn?” “What does this CVO have to learn?”

Ian Williams (Williams 2007), in a comprehensive summary of UK nonprofit operations, writes “Without learning at different levels in a CVO there is no innovation, change and growth in impact, influence, scale, and scope of operation. Questioning and improving how a CVO learns needs to be continually advanced and specifically included in the organization’s strategy.”

Training should be high standard and targeted at staff facing similar issues and needing similar training: training is at its best when you are with people of similar ability; like tennis playing with more experienced people is not invigorating, nor is playing people who are much worse.

Training should not just be “sheep-dipping,” processing large numbers staff quickly through courses; there is a danger that a great deal of training now seems to be about ticking boxes and ensuring compliance with tendering requirements. There is sometimes too little consideration in design and delivery of courses of how different are everyone’s capabilities and requirements. This has worsened with the introduction of some poor online training; staff tell each other the shortcuts to complete these courses quickly because they are too rigid and unsophisticated, lacking application to real situations.

Staff training and continuous professional development need to be structured into annual appraisals to assess progress and suggest appropriate courses. If retraining was not considered for someone who underperforms, this can be grounds for suing for constructive dismissal.

Staff Performance

Peter Drucker (Drucker 1990) states that CVOs need to give priority to performance and results as he felt that in general they tend not to give enough emphasis to this (He was writing before output related contracts were brought in). He believed that performance and results are far more important—and far more difficult to measure and control—in CVOs than in a business. Performance is the ultimate test of an organization, as very CVO exists for the sake of performing well in changing people and society. “The ultimate question which I think everyone in the CVO should ask again and again and again, both of themselves and the organization is: “what should I hold myself accountable for by way of contribution and results?”” And then of the CVO: “What should this organization hold itself accountable for by way of contribution and results?”

The aim of managing performance is to manage in such a way that you improve the performance of both staff and that of the organization continuously. It involves making sure that the performance of employees contributes to the goals of their teams and the business as a whole.

You as the manager must generate an atmosphere of high standard performance in the team; some of this will be team work, some will be motivating individual staff, some will be developing a structure in which the manager gives regular feedback on performance in appraisals, some will be in the pay structure (see Business Plans), some will be that staff feel they themselves are contributing ideas to the organization; there is some evidence that pioneering projects produce better results, presumably because of better staff motivation.

Performance Management

To manage staff performance effectively, it is essential that managers set an example themselves. The Macleod Report12 recommends that managers should:

• Behave in a consistent way.

• Ensure work is designed efficiently and effectively and provide clarity about what is required from people.

• Provide regular performance feedback and coaching.

• Facilitate and empower rather than control and restrict.

• Understand their people as people and know what makes them tick.

• Treat people fairly, with respect and appreciation.

• Are committed to developing and rewarding their people.

• Get the best out individuals and the team.

• Work at being inspirational role models for their people.

Strategy to Engage Staff

Although there is no master model for successful staff engagement, the Macleod Report suggested that there were four common themes from their research. The key elements to support successful employee engagement were:

• Strategic narrative; visible, empowering leadership providing a strong strategic narrative about the organization, where it’s come from and where it’s going.

• Engaging managers who focus their people and give them scope, treat their people as individuals and coach and stretch their people.

• Employee voice throughout the organizations, for reinforcing and challenging views, between functions and externally. Employees are seen not as the problem, rather as central to the solution, to be involved, listened to, and invited to contribute their experience, expertise and ideas.

• Organizational integrity—the values on the wall are reflected in day to day behaviors. There is no “say–do” gap. Promises made and promises kept, or an explanation given as to why not.

Managing Teams Remotely

Some teams are dispersed around several locations, with some staff working from home sometimes. In these cases new media becomes useful for communication and support; a midwives social enterprise uses WhatsApp to share information and good practice. However in some cases it is essential to set up face-to-face team meetings; a recruitment company found that performance improved after this was introduced.13

Assessing Poor Performance and Inappropriate Behavior

Occasionally an individual staff member is not performing their job unsatisfactorily over time. Or someone may be displaying inappropriate behavior at work. Both these can have a very detrimental effect on other staff, particularly if this is not taken up by management.

First make absolutely sure there is a real issue about someone’s poor performance. Record events and timescales in great detail in contemporaneous notes, otherwise you will lose out legally. Also you must follow your organization’s disciplinary code and employees’ contracts.

To make sure you are dealing with a real problem, make sure you can answer these questions:

1. Do you know exactly what the behavior is and how it is below standard? Can you define exactly is causing concern? Could you describe it to a third party? Feelings are not enough; any specific examples with evidence rather than generalized assertions?

2. Is this behavior causing a problem? Is the behavior just irritating or is it having a definite impact on the service? Is time and money being wasted in a quantifiable way? Are other staff clearly and justifiably being upset?

3. Would other managers see this behavior in the same way? Are you interpreting this the right way? Would another manager accept your concerns as reasonable?

4. Are you being overdemanding or taking something personally? An example could be one’s personal dislike of untidy desks, which doesn’t always mean that the person is disorganized. You could be putting too much emphasis on too little evidence and personal idiosyncrasies.

Only when you have satisfied yourself in all four areas is it time for action. You must demonstrate this behavior is detrimental to the organization and be sure that you are dealing with a real problem which others would see objectively in the same light.

Reasons for Poor Performance

There can be a range of reasons for poor performance which you will need to properly consider. These include:

• Personal ability: Has the individual the right skills? Is there a skills gap needing training?

• Manager ability: Have you given enough direction, and made sufficient support and resources available?

• Process gap: Have the goalposts moved to make a task unattainable? Have there been regular enough reviews and sufficient training on offer?

• Organizational forces: Has the organization created red tape overkill, cultural restrictions, or hidden agendas which make the task impossible?

• Personal circumstances: Has something at home affected performance at work?

• Motivation: Is the person demotivated or suffering from stress or lack of challenge?

Managing Poor Performance

When you are satisfied you are being objective about poor performance, the steps the manager needs to take are as follows:

• Discuss the issue with the staff member concerned, providing feedback.

• Try to get to the root of the issue.

• Explore the options and alternatives available.

• Agree the next steps and clear objectives to improve, with regular meetings to check progress.

• Provide additional training and coaching if appropriate.

• Monitor and document progress.

• Help them or help them out; don’t ignore the problem.

Discipline

If staff disciplinary action is required, this can be a tricky area unless you follow your organization’s disciplinary code to the letter, as well as employers’ contracts, and current legal requirements. Wherever possible ask for HR support at an early stage where it exists in the organization and if not there are specialist lawyers available. Union reps may need to be involved in any meetings (A performance monitoring and management system in the nonprofit sector is included as an appendix to this chapter.).

Managing Volunteers

Volunteer input and commitment is an enormous part of the nonprofit sector, arguably both its greatest strength and resource. The American Red Cross has 500,000 volunteers along with 30,000 staff, while the UK Samaritans has over 21,000 volunteers in 200 branches. Thus, managing their recruitment, deployment, work and support is an essential but specialist skill in nonprofit sector organizations.

Any organization working with vulnerable adults or children should also have proper vetting and criminal record checking procedures in place for volunteers (and staff of course), along with a relevant program of induction and training. Another issue is retention, as the turnover for younger volunteers can be very high as they enter full-time employment, while consulting volunteers on policy matters can also become important.

Possibly the most significant group of volunteers are of course nonprofit trustees, whose recruitment and roles are vital; this subject is covered in the Governance chapter.

Some nonprofit organizations appoint specialist volunteer coordinators to recruit and support volunteers; while others develop structures with designated “lead” senior volunteers, to train new volunteers and set an example; one such organization is the British Red Cross. Certain nonprofits contract out their volunteer recruitment to specialist nonprofits, such as Volunteer Match.14 While volunteers will not have the same employment rights or financial benefits, such as pensions, it is important to make sure that they are treated properly and with respect. Any expenses need to be sorted out in a rational and transparent system. As already stated advice is available from national nonprofit support organizations in the U.S.15 and UK.16

Conclusion

Managers need to set up in their organizations the appropriate HR structures to run effectively and to develop; luckily there is great deal of free assistance for this available through networks as well as those that charge for their services. This must be a priority even in small organizations otherwise staff will not flourish or remain.

References and Further Reading

ACEVO. 2006. “Doing Good and Doing Well - Defining and Measuring Success in the Third Sector.”

Ashraf, N., O. Bandiera, and B.K. Jack. 2014. “No Margin, No Mission? A Field Experiment on Incentives for Public Service Delivery.”

Clarke, Nita; 2013. Interview co-author “Engage for Success”; Great Workplace Special Report, Guardian.

Collins, J. C., and Collins, J. C. 2005. Good to great and the social sectors: why business thinking is not the answer: a monograph to accompany. Boulder, CO: J. Collins.

Community Matters. 2009. A Vision for Neighbourhoods, Report accessed in 2015; Communities Matters has now closed down.

Daily Telegraph. 2013. http://www.telegraph.co.uk/finance/newsbysector/retailandconsumer/10146737/Google-brand-damaged-by-tax-row.html

Drucker, P. 1990. Managing the Non-Profit Organization; Practices and Principles. New York: Harper Collins.

Furedi, F., and Bristow, J. 2012. The Social Cost of Litigation. London, England: London Centre for Policy Studies.

Handy, C.B. 2006. Myself and other more important matters. London: William Heinemann.

Landström, H. 2005. Pioneers in Entrepreneurship and Small Business Research. New York: Springer Science+Business Media,

Larkin J. 2012. “The Most Powerful Workplace Motivator.” http://studymode.com/essays/The-Most-Powerful-Workplace-Motivator-1097447.html

St Mungos 2015 http://www.mungosbroadway.org.uk/apprenticeship_scheme

Williams, I. 2007. “The Nature of Highly Effective Community and Voluntary Organizations” http://www.dochas.ie/sites/default/files/Williams_on_Effective_CVOs.pdf

Performance Monitoring System

“Doing Good and Doing Well—Defining and Measuring Success in the Third Sector” (ACEVO 2006). In this report, 10 recommendations were made for developing a sound performance monitoring and management system:

1 https://www.theguardian.com/voluntary-sector-network/2013/aug/06/charity-fat-cats-paid-too-much

2 http://www.guidestar.org/Home.aspx

3 https://knowhownonprofit.org/tools-resources/hr-policies

4 https://www.shell-livewire.org/listing/business-library

6 https://www.ncvo.org.uk/practical-support/information/volunteer-management

7 https://www.ncvo.org.uk/ncvo-volunteering/find-a-volunteer-centre

8 http://www.pointsoflight.org/handsonnetwork

9 https://iiv.investinginvolunteers.org.uk/

10 https://www.nonprofithr.com/portfolio/essential-nonprofit-employee-handbook-template/

11 https://knowhownonprofit.org/people/employment-law-and-hr/policies-andtemplates/handbook

12 http://engageforsuccess.org/engaging-for-success

13 http://timewise.co.uk/knowledge/research/

14 https://www.volunteermatch.org/

16 https://www.ncvo.org.uk/practical-support/information/volunteer-management