Italian Economy and Governance Model from a Global Perspective

A Historical Overview of the Italian Economy

Before the 20th century, the Italian economic system was mainly rural and the industrialization process was limited to the North of the country and to some industries (above all the mechanical and the textile). At the beginning of the 20th century, Italian economy joins the second industrial revolution, thanks to the important role played by the State that controls a number of companies operating in key industries such as public utilities, steel, insurance, and banking. In the first decades of the 20th century, two subjects, that is state-owned companies and large universal banks (e.g., Banca Commerciale Italiana, Credito Italiano, and Banco di Roma), dominate the national economic system as they finance the investment and the growth of companies operating in the capital-intensive industries such as public utilities (energy, telecommunication, etc.), steel, and mining.

The roots of Italian capitalism as it is nowadays are to be found in the Italian State’s reaction to the Great Crisis of 1929. The negative economic consequences affect first the industrial companies, and then the large universal banks that control them. The three main Italian universal banks collapsed due to the financial distress of their controlled companies. It emerged that an important part of nonfinancial firms was run by “mere executives using money provided almost entirely by the depositors of the commercial banks” (Saraceno 1955: 198). Since the banks’ losses were eventually covered by the State, such a situation created moral hazard.

In 1933, to avoid potential terrible consequences for the entire national economy, the Italian Government creates a holding company (called IRI or Istituto per la Ricostruzione Industriale), which buys universal banks’ shareholdings in industrial companies. IRI’s board of directors was fully under the control of the Italian Government (Saraceno 1955). At the end of this massive reallocation of shares, the IRI group becomes the controlling shareholder of a large number of Italian companies and banks.

A second effect of the Great Crisis, following the evolution of the U.S. legislation (in particular, the 1933 Glass–Steagall Act), was the issue of a new banking law in 1936. This law prohibited “universal” banks. Banks were not allowed to hold equity stakes in nonfinancial firms in order to avoid the possibility that the instability of industrial companies could have serious economic consequences on the financial industry (Amatori and Colli 2001). Since then, banks have generally preferred an arm’s-length relationship with their customers rather than relational financing. This picture of bank behavior has one notable exception, Mediobanca (see Box 1.1).

The State intervention in the economy through the IRI group, originally intended as temporary, becomes permanent in 1937, characterizing the Italian capitalism as a “mixed economy” (Barca and Trento 1997b). Since then, the State dominates the national economy through some large industrial business groups such as IRI, controlling a number of large companies operating in different industries and the largest banks in the country, ENI (Ente Nazionale Idrocarburi), controlling companies in the oil industry, EFIM (Ente Partecipazioni e Finanziamento Industrie Manifatturiere), controlling companies in the mechanical sector, and ENEL (Ente Nazionale per l’Energia Elettrica) producing and distributing electricity in the country.

Besides the State, also some large private groups controlled by wealthy entrepreneurial families promoted the growth of the national economic system. Some business groups are relatively old and have been founded between the end of the 19th and the beginning of the 20th century. They are Fiat group (Agnelli family), Pirelli group (Pirelli family), Italcementi group (Pesenti family), SMI (Società Metallurgica Italiana) group (Orlando family), and Acciaierie e Ferriere Lombarde Falck group (Falck family). These long-lasting groups are typically localized in the north of the country and are controlled by wealthy families of entrepreneurs who are strictly connected by personal relationships, mutual shareholdings, and syndicate pacts. For their characteristics, they have been called the galaxy of the North (galassia del nord) of the Italian capitalism. In the long period of growth of the national economy that follows the Second World War, also known as the Italian economic miracle (miracolo economico), new families entered into the scene. They founded and developed important business groups such as Ferrero, Benetton, De Benedetti, and Fininvest of Silvio Berlusconi.

Box 1.1 The History of Mediobanca: The “Hub” of Italian Capitalism

Founded in 1946 under the initiative of Raffaele Mattioli, the chairman of the Banca Commerciale Italiana, and Enrico Cuccia, Mediobanca offered a wide set of activities to its industrial and financial customers, including the placement of their bonds and shares and the advice on strategic and financial issues.

Mediobanca was formally controlled by some of the largest banks in Italy (Banca commerciale, Credito Italiano, and Banco di Roma), but de facto independent and under the strong leadership of its chief executive officer (CEO), Mr. Enrico Cuccia, who exercised his power until his death in 2000.

Not only did Mediobanca act as a merchant bank, but also played an important role in corporate governance, being able to influence CEO turnover of nonfinancial listed firms. This role was not justified by the relatively small proportion of shares directly held by Mediobanca in Italian nonfinancial listed firms, but by the fact that Mediobanca was the “hub” of the main cross-shareholding network (including shareholders’ agreements) among the most important industrial groups in Italy.

Sources: Barca and Trento (1997a); Aganin and Volpin (2005); Colli (2009); Zattoni and Cuomo (2016).

After the Second World War, small and medium enterprises (SMEs) have significantly increased their importance within the national 6 A PrIMEr oN CorPorAtE GoVErNANCE economy. These companies are usually controlled by an entrepreneur or a family and operate in small industries or niches of large industries. The most competitive Italian SMEs are usually diffused within limited geographical areas (the so-called industrial districts) where there is a high density of companies operating in a strictly related cluster of industries (Porter 1990). So, for example in Sassuolo, where there is the district of the ceramic tile production, it is possible to find not only the most competitive producers of ceramic tiles, but also the most sophisticated suppliers of goods and service related to the production of ceramic tiles.

Finally, the Italian economic system is also characterized by a large number of cooperatives—that is, worker cooperatives, consumer cooperatives, social cooperatives, or consortiums—operating in several businesses (e.g., services, agriculture, retail, manufacturing, construction, and banking). The large number of cooperatives—there are something less than 80,000 cooperatives employing about 1.3 million workers in Italy—has been favored by both cultural and political values and the presence of tax incentives (Zattoni 2015). While some cooperatives are small and play a limited role in their industry, other cooperatives are large and play a leading role at national or international level. Think, for example, of Coop Italia in the domestic retail business, Sacmi in the global production of machineries for ceramic tiles, or CMC in the national and international construction business.

In sum, various actors played a leading role and promoted the national economic development along the time (see Table 1.1). Between 1900 and 1930, during the first phase of the industrialization process, the State and some large universal banks dominated national economy, with a minor role of wealthy entrepreneurial families and cooperatives. In the second phase, when the financial crisis of the 1930s pushed the Italian Government to dismantle universal banks and to buy their shares in industrial companies, the state became the most important shareholder and the driver of the national economic development, flanked by an increasing role of entrepreneurial families and cooperatives after the Second World War. In the current phase, that is, after the large privatizations and the new banking law of the 1990s, entrepreneurial families are the key drivers of the national economy together with the state.

Table 1.1 The role of main actors within major periods of national economy

|

1900–1930 |

1930–1992 |

1992–current |

Major events in the period |

Take off of industrialization |

Economic crisis followed by the economic miracle New banking law separating commercial and industrial banks Large nationalization |

Stagnation of economic development New banking law allowing commercial banks to own shares in industrial companies Large privatization |

State |

Highly involved as entrepreneur in capital-intensive industries |

Highly involved as entrepreneur in a number of industries |

Focused on key strategic industries |

Entrepreneurial families |

Involved as entrepreneurs of large companies |

Highly involved as entrepreneurs of small and large companies |

Highly involved as entrepreneurs of small and large companies |

Banks |

Universal banks as controlling shareholder of large companies |

Commercial banks providing loans and investment banks owning shares in industrial companies |

Commercial banks can buy shares in industrial companies (especially to solve financial crisis) |

Cooperative |

First development of cooperatives |

Stagnation during fascism regime and development after the Second World War |

Significant presence in several industries and regions |

The Main Characteristics of the Italian Economy

The Italian economy experienced an intense economic growth during the first decades after the Second World War with an average annual increase of gross domestic product (GDP) over 5 percent. In the following decades, the annual increase of GDP was aligned with major European countries, with 3.3 percent in the 1970s and 2.4 percent in the 1980s. Since then, the national economy became stagnating, with an average annual increase of GDP moderately positive or close to zero. Despite this slow growth, Italy is still the 8th national economy in the world and its GDP equals to €1,608 billion ($1,815 billion) in 2015 (World Bank).

The structural characteristics of the national economy include the huge national debt, few structural dualisms (e.g., North and South, small and large firms, traditional and hightech industries), the specialization in manufacturing, and the high level of state intervention.

(a) The huge national debt. The national debt is something less than €2,249 billion ($2,539 billion) at the end of June 2016, with a percentage on GDP over 130. This is one of the highest percentages among European countries—during the financial crisis Greece overcame Italy—and one of the highest among the national world economies, lead by Japan whose national debt on GDP is over 220 percent. The huge national debt is a real economic issue as it generates high interests and a risk of a speculative attack by financial markets (as experienced in the summer of 2011). However, according to some commentators, the risk should not be too much emphasized as both Italian families are great savers owning a large amount of the national debt and a recent study considering both the explicit and the implicit national debt (i.e., the debt due to agreements to cover future welfare expenses) shows that Italy has the lowest ratio (i.e., 57 percent) within the EU (Fortis 2016).

(b) Some structural dualisms. Italian economy is characterized by some dualisms referring to a structural divide between North and South, small and large firms, and traditional and high-tech industries. First, more than 50 percent of companies are localized in the North area of the country. The Center and, above all, the South have a significantly minor number of companies and, consequently, also of employees (Istat 2013). Despite the large investments made by Italian Governments to contribute to its economic development, the South is still relatively underdeveloped and has a higher (overall and youth) unemployment rate respect to the North. Still today how to fill the gap between the North and the South of the country is an open issue.

Second, while large State- and family-owned groups played a significant role within the national economy, the Italian economic system is above all characterized by a very large number of small and medium companies (SMEs). More than 95 percent of the 4,425,950 firms operating in Italy have, in fact, less than 10 employees (Istat 2013). Moreover, Italian economy is characterized by a relatively large number of self-employed workers, which are 5,119,968 compared to 11,304,118 employees. In sum, as the national economic system is dominated by SMEs, Italian companies may lack the necessary resources to play a leading role in scale- and research-intensive industries or in global markets.

Third, most of the Italian firms operate in traditional industries, such as food, wine, textile, fashion, jewels, ceramic tiles, machinery, and construction. Very few companies compete with success in high-tech industries on a continental or global scale. Think, for example, of some SMEs in biotechnology, or large companies such as Yoox-Net a Porter in the fashion e-commerce, STMicroelectronics in microchips and semiconductors, and Leonardo (previously called Finmeccanica) in the defense industry. In sum, the national economy is focused on traditional economies and lacks a significant number of innovative companies able to gain a leading position in high-tech industries.

(c) A significant weight of manufacturing. In terms of sectoral distribution, the 16,424,086 employees of Italian companies are working above all in manufacturing and construction (33 percent), followed by services to the firms (29 percent), and trade, hotel, and catering (28 percent). Sectors with minor importance are other services, health care, education, and agriculture (Istat 2013). The large weight of manufacturing is both a weakness and a strength: on the one hand, in the last decades the globalization promoted the offshoring of several low-cost productions to emerging economies (e.g., white goods, electronics); on the other hand, Italy is still the second largest manufacturing economy in Europe (after Germany) and has specialized skills and knowledge in some industries (e.g., fashion, leather, mechanics, wine).

(d) The high level of state intervention. The state has been always very active in the national economy. Especially after the financial crisis of the 1930s, the State had a large and sometimes dominant role in the national economy, thanks to the direct control on some large conglomerates (e.g., IRI, ENI, and EFIM). Its influence was so large that the Italian Government decided to create in 1956 a Ministry of the state-owned companies (Ministero delle Partecipazioni Statali). After 1992, instead, the State decided to privatize a large number of companies in order to: (i) redesign the structure of the national economy, (ii) improve the profitability of several industries, (iii) decrease the national debt, and (iv) increase the liquidity and relevance of the stock exchange (Zattoni 1995). Thanks to this massive privatization process (still in progress), the state collected more than €120 billion and reduced its entrepreneurial role to few large companies operating in key strategic industries.

A Brief Overview of the Italian Corporate Governance Model

The Italian corporate governance model belongs to the so-called Latin model together with France, Spain, Belgium, Portugal, and Greece. This governance model is characterized by large shareholders and a limited role of the financial markets. As such it differs from the Anglo-American market model and may be considered a variant of the German–Japanese network model.

Large Shareholders

The most recent ranking of the 10 largest Italian companies and groups by revenues shows that only two groups—one state-owned group listed on the stock exchange (ENI) and one family-owned group with a focus on the auto and truck business (EXOR)—have more than €100 billion of revenues in 2014 and only three, the two mentioned before plus ENEL, overcomes €50 billion of revenues in 2014 (Table 1.2). The data shows that the first three groups have a much bigger size than the remaining ones.

The table also shows that none of the first 10 companies is widely owned. Three out of 10 are unlisted and controlled by the State (GSE), a family (Edizione) or a foreign multinational company (Esso). The seven large companies that are listed on the stock exchange are not widely held, but controlled by the state (ENI, ENEL, and Leonardo), a family (EXOR and Saras), or a foreign multinational firm (Telecom Italia and Edison).

Table 1.2 The largest Italian companies in 2014 (data in million euro)

Ranking |

Frim/Group |

Listed |

Main shareholder |

Revenues |

Financial debt |

Employee |

1 |

EXOR |

Yes |

Family |

122,246 |

60,189 |

318,562 |

2 |

ENI |

Yes |

State |

109,847 |

25,891 |

84,405 |

3 |

ENEL |

Yes |

State |

74,251 |

57,032 |

68,961 |

4 |

GSE—Gestore servizi energetici |

No |

State |

32,076 |

227 |

1,224 |

5 |

Telecom Italia |

Yes |

Forigen |

21,124 |

34,597 |

59,285 |

6 |

Leonardo |

Yes |

State |

14,663 |

5,770 |

54,380 |

7 |

Edison |

Yes |

Forigen |

11,932 |

2,371 |

3,140 |

8 |

Esso italiana |

No |

Forigen |

11,450 |

376 |

1,265 |

9 |

Edizione |

No |

Family |

10,900 |

16,190 |

63,474 |

10 |

Saras |

Yes |

Family |

10,103 |

654 |

1,935 |

Source: Mediobanca (2015).

A focus of the last census allows us to mature a deeper knowledge on the ownership structure of all Italian companies (Istat 2013). Data shows that more than 90 percent of Italian companies are directly controlled by a person, less than 8 percent are controlled by another firm, a bank or a holding company, and less than 1 percent by the State or the public administration in general. These percentages tend to be higher among smaller companies where the ownership structure is more concentrated in the hand of one person. The opposite is true for companies with more than 250 employees, as about 69 percent of these companies is controlled by another company, a bank or a holding company, and only 25 percent of them is controlled by a person.

In sum, Italian companies (listed or unlisted, large or small) are, in almost all cases, under the dominant influence of a large shareholder that is usually a family. Despite the large privatization process and the liquidation of the state-owned IRI group in 2002, the Italian State and the local public administrations continue to hold relevant shareholdings in some large listed and unlisted companies (Zattoni 2009). Finally, a number of large Italian companies are subsidiaries of large foreign multinational companies.

The Stock Exchange

The capital market has a limited role in providing financial funds to companies. The national financial system has always been bank-oriented as companies prefer to rely on the financial debt (bank loans and bonds) and on retained earnings than on the equity market to finance their future investments. Consistently, after some decades where Initial Public Offerings (IPOs) overcome delistings and the number of listed companies slightly increase, there are about 300 listed companies on the National Stock Exchange (Table 1.3).

The Italian Stock Exchange tried to encourage the listing of new companies creating different market segments targeted to different companies. The main markets (MTA, Mercato Telematico Azionario and Expandi) of Borsa Italiana are regulated markets under the definition given by the Mifid Directive, while the “junior” markets (Alternative Investment Market [AIM Italy] and Mercato Alternativo del Capitale [MAC]) are multilateral trading facilities designed for small and medium companies. This distinction is of particular importance since the EU financial legislation only applies to companies whose securities are listed in a regulated market (Zattoni and Mosca 2012).

Table 1.3 The number of companies and shares listed on the Milan Stock Exchange (1960–2016)

|

Regulated markets |

Multilateral trading facilities |

Total |

|||

Main Mkt/MTA & Others |

MAC & AIM |

|||||

Year |

Companies |

Shares |

Companies |

Shares |

Companies |

Shares |

1960 |

140 |

145 |

— |

— |

140 |

145 |

1970 |

132 |

144 |

— |

— |

132 |

144 |

1980 |

169 |

199 |

— |

— |

169 |

199 |

1990 |

266 |

378 |

— |

— |

266 |

378 |

2000 |

297 |

361 |

— |

— |

297 |

361 |

2010 |

278 |

310 |

18 |

18 |

296 |

328 |

2016 |

244 |

261 |

80 |

80 |

324 |

341 |

Source: Borsa Italiana

Among the many Italian companies that are still privately owned, there are also large multinational groups such as Barilla, with revenues about €3.3 billion in 2015, and Ferrero, with revenues about €9.5 billion. Several reasons contribute to explain the low attitude of Italian companies to go public: the tax advantage of financial debt versus equity as financial interests can be partially deduct from taxable income; the unwillingness of controlling shareholders to share or to disclose the most important decisions with minority shareholders in the shareholders’ meeting or with independent directors in the boardroom; the regulation and the cost of going public that in the controlling shareholders’ view may reduce the flexibility and the profitability of the company.

Owing to these (real or perceived) obstacles to go public, in July 2016 there are 324 companies listed in the National Stock Exchange: 244 companies listed on MTA market and 80 listed on AIM-MAC. The total market capitalization is €469,473 million (something less than 30 percent of the GDP): €466,813 million for the MTA and €2,659 for AIM-MAC (Borsaitaliana). The market capitalization of the Financial Times Stock Exchange Milano (FTSE MIB) index—which includes the largest 40 companies—is €372,036 million, almost 80 percent of the total market capitalization.

The Privatizations: A Missed Opportunity to Create Widely Held Listed Companies

The privatization of a number of state-owned companies represented a unique opportunity to change Italian capitalism. One of the most debated issues by the Italian Government was how to make evolve the ownership structure of the privatized firms. The Government was divided between two options, that is to favor the creation of either the Anglo-American dispersed ownership model, where the shareholdings are diffused among a large number of small investors (families and institutional investors), or the French noyaux durs (core group) model, where the shareholdings are concentrated in the hands of a stable group of large investors (large companies and banks).

Both solutions imply advantages and disadvantages. The Anglo-American model has the advantage to emphasize the importance of the stock exchange and the financial market culture in the national economy, but at the expense to leave privatized groups without a stable national controlling shareholder. The French model favors the creation of a selected and stable group of shareholders that can guarantee an adequate financial and strategic support to the long-term development of the firms; on the other hand, it moves these groups in the hands of some financial and private groups that can extract personal benefits at the expense of minority shareholders and inhibits the effective functioning of an active market for corporate control. As at the end both options present pros and cons, the Government decided that there was not a preferred model of ex post ownership structure, and that it would have decided case by case based on the characteristics of each privatized company.

In order to keep control rights in the privatized companies, the State created the possibility to issue a golden share. These shares confer special power to the State and their purpose is to safeguard the national interests in companies that operate in strategic industries such as, for ItALIAN ECoNoMY ANd GoVErNANCE ModEL 15 example, the public utilities (i.e., energy, transportation, and broadcasting). The golden shares give the Government some special rights such as to oppose the acquisition of blockholdings by hostile raiders or to veto decisions about relevant changes of core characteristics of the firm (e.g., liquidation, merge, relocation of headquarters abroad, and radical change of the business or of the bylaw).

The Italian privatization process confirms how difficult it is to design ex ante the ownership structure of state-owned companies after the privatization. The sale of small blocks of companies’ shares to a large number of investors does not lead automatically to the creation of a widely held company. On the contrary, this decision can favor the acquisition of the control by few coordinated shareholders owning a relatively small fraction of the voting rights. As the facts following the massive privatization process shows, the dispersed ownership model cannot be created through an edict of the Government, but it is the result of an efficient and liquid capital market where mature and informed investors (families and firms) and financial intermediaries (banks, insurance companies, and above all institutional investors) operate supported by strong investors’ rights. If these crucial conditions are absent, the decision to create a widely held company can fail and the control rights can be transferred from the State to a number of coordinated shareholders.

Despite the privatization failed to create widely held listed companies, they changed, in some cases, the structure of some important industries of the national economy. For example, Nuovo Pignone is today an important part of General Electric group, Banca Commerciale, and Credito Italiano have become—after several mergers and acquisitions—the two largest national banks (now called, respectively, IntesaSanPaolo and Unicredit), the food company Pavesi is part of the Barilla group, the steel company Dalmine belongs to the Tenaris group, and so on. Also after this long trend of privatizations, the State or the public administration still play an important role in the national economy, even if much smaller than in the past. Currently, the State owns, directly or through the Cassa Depositi e Prestiti (CDP), the control of some of the largest groups operating in strategic industries, for example ENI (oil and gas), ENEL (electricity production and distribution), Terna (transmission of electricity), Snam Rete Gas (distribution of gas), and Leonardo (defense). Moreover, some municipalities control large public utilities groups listed on the stock exchange such as A2A, ACEA, Hera, Iren.

An Introduction to the Corporate Governance of Italian Companies

As a consequence of the high ownership concentration and the dominance of large shareholders, the key governance problem of Italian companies is not the potential conflict between principal and agent (i.e., shareholders and top managers) characterizing Anglo-American companies, but that one between principal and principal (i.e., controlling and minority shareholders) (Melis 2000; Zattoni 2009). This conflict happens because the controlling and the minority shareholders both have different levels of information and power, and may pursue different interests.

First, the two classes of shareholders have different influence on shareholders’ and boards’ decisions. On the one hand, large shareholders own enough shares to influence assembly’s decisions, to elect either themselves or their fiduciaries as board members, and to control top managers. On the other hand, small shareholders have no (or limited) influence on both shareholders’ assembly meetings and, consequently, also on board decision making. It follows that while large investors are actively engaged in influencing firms’ key decisions, small investors are generally passive, that is they do not attend shareholders’ meetings and do not exercise control on assembly’s or board’s key decisions.

Second, large and small investors have also different interests around the company. Large investors want to take or to influence key decisions about the governance or the strategy of the firm, and have enough information and power to control top managers’ actions. Boards and top managers usually take decisions in the interests of all shareholders, but they can also pursue the interests of the controlling shareholders at the expense of the minorities. For example, they can distribute excessive remuneration or sell with a discount (buy with a premium) company’s assets to related parties transactions (see Chapter 2). Small investors are, instead, usually interested in the cash flow coming from their investment (i.e., the capital gain and the dividends distributed). As small investors may not attend assembly meetings or may not even bother to vote, when dissatisfied they penalize the board and the top managers by selling their shares on the market (i.e., they vote by feet).

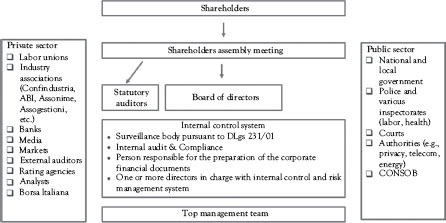

In order to minimize the risk of misappropriation of minority investors, the Italian corporate governance model of a joint stock company comprises a number of governance bodies and actors inside and outside the firm (see Figure 1.1). Internal governance bodies include the board of directors, the board of statutory auditors (in the traditional governance model) and the internal control system. In addition, several external actors from the private sector play a governance role to protect their interests or to analyze and evaluate the quality of firm’s processes and outcomes. Finally, also a number of actors from the public sector play a governance role by defining laws and regulations, monitoring firm behavior and results, imposing sanctions in case of misbehaviors.

More in depth for what concerns internal governance bodies, and with specific regard to the traditional governance model, the shareholders’ meeting nominates not only board members but also a board of statutory auditors with specific control tasks (see Chapter 6) and, in companies that are listed or sell bonds to the public, also an external auditor checking the accuracy of the financial reports (see Chapter 3). Still within the company, there is a surveillance body (so-called 231 committee) aimed at checking the compliance with legislative decree 231/01 that imposes on companies an administrative liability for crimes committed by directors or employees in the interest of the company itself. Finally, companies may also establish an internal audit and compliance unit with the task to audit internal processes and provide suggestions on how to prevent risks. In listed companies, there are also two additional roles, the person responsible for the preparation of the corporate financial documents and one or more directors in charge of establishing and maintaining the internal control and risk management system.

Figure 1.1 The Italian corporate governance model

The actors performing a governance role outside the firm can be divided in two groups: the private actors and the actors belonging to the state or the public administration. Among the private ones, several actors play a governance role typically to protect specific interests. The labor unions are interested in protecting the employment, the remuneration, and the working conditions of employees. At the national level, labor unions are divided into three major groups with different political orientation (Confederazione Generale Italiana del Lavoro [CGIL], Confederazione Italiana Sindacati Lavoratori [CISL], and Unione Italiana del Lavoro [UIL]). Especially when they share the same view on the debated issue, they may have a significant influence on the negotiation.

The industry associations tend to protect the interests of their members in the negotiation with other parties, for example the Government, the labor unions, and so on. The most important ones are Confindustria, the association of Italian entrepreneurs; ABI, the association of Italian banks; Assonime, the association of joint stock companies; and Assogestioni, the association of institutional investors. The major objective of these associations is to promote the interests of their members in relation to the Government, the legislator, and other major stakeholders (e.g., labor unions, regulators, authorities).

After the banking law issued in 1936 in order to separate commercial and investment banks, Italian banks do not play a significant role either as major shareholders of industrial companies, or (with few exceptions) as providers of advisory services. As such they have a lower influence than German house banks. However, after the most recent banking law issued in 1992 and aimed at lessening the separation between commercial and investment banks, they may play a significant governance role in some specific situations, for example when companies face a financial distress and need further capital from the banking system.

The media can potentially play a relevant governance role as they may disseminate relevant and independent information on companies, so increasing transparency and the efficiency of external monitoring. However, as we will see later (Chapter 4), they are either controlled by the state (and so are under the influence of political parties) or by wealthy entrepreneurs owning also large industrial groups.

External auditors, credit rating agencies, and analysts provide relevant information influencing investors’ buying and selling decisions, and so affecting the overall efficiency of financial markets. The key issue is their independence from corporate actors as, for example, auditors and rating agencies are hired and paid by the same firms they audit or rate. A potential conflict of interests affects also corporate analysts if the legal or Chinese walls between the bank business units do not clearly separate the analysts’ recommendations from the investments’ decisions. The recent evolution of the legislation tried to address the potential conflict of interests affecting these external actors to improve their ability to effectively perform their important roles. Future events will say if the current legislation may prevent all conflicts of interests or should be further strengthened.

Borsa Italiana S.p.A. has been created in 1997 to privatize market exchanges and is effective since January 1998. After the merger of October 2007, Borsa Italiana is now part of the London Stock Exchange Group and its main goal is to increase the efficiency, the transparency, and the liquidity of its financial markets. To reach this purpose, Borsa Italiana both defines rules and procedures for issuing companies and financial intermediaries, and supervises transaction activities and listed companies’ disclosure.

The most important actor of the public sector performing a governance role is obviously the national Government and, in some cases, also the local one. The national Government is a key actor as it establishes laws and rules for the business. As we will see (Chapter 2), corporate law has been modified several times in the last decades in order to prevent or minimize the consequences of corporate scandals, and to align the core norms to international standards.

Police and inspectorates play a control role on several aspects of corporate life. For example, Guardia di finanza is a military police with competence on economic and financial matters (e.g., financial crimes, smuggling, or drug trade); NAS (Nucleo Antisofisticazione e Sanità) is a peculiar police structure aimed at preventing crimes related to food that may cause serious issue to human health; and so on.

The courts play a relevant governance role as several stakeholders can appeal to its judgment if their rights are infringed. Courts are usually a remedy of last resort, that is, stakeholders appeal to the court when all other preemptive or subsequent remedies have been ineffective to solve the controversy. Unfortunately, this remedy is not particularly effective in Italy as the judicial system is considered slow and inefficient. Civil court cases may, in fact, take several years before to reach a definitive decision.

In the last decades, several authorities have been created to perform specific governance tasks. The oldest one is the CONSOB (Commissione Nazionale per la Società e la Borsa) established in 1974 to protect investors and to ensure the efficiency and the transparency of the financial markets. Other important authorities established in the following years include IVASS (Istituto per la Vigilanza sulle Assicurazioni Private e di interesse collettivo) to monitor insurance companies (1982); Antitrust (Autorità garante della concorrenza e del mercato) to prevent dominant positions that may undermine fair market competition (1990); the Authority for energy and gas (1995) to establish quality service levels, protect customers’ rights, and monitor service providers; the Authority for communication to promote fair competition and assure good quality services in telecommunication and media industries (1997).

Key Points to Remember

The Italian economy started the industrial revolution at the beginning of the 20th century. In the first phase the state and universal banks dominated the national economy. After the 1930s, the state and wealthy entrepreneurial families promoted the national economic development. More recently, families controlling small and large companies—together with cooperatives and the state in some key industries—are the most important players of the national economy.

The structural characteristics of the national economy are a huge national debt, some dualisms (i.e., North vs. South, large vs. small firms, traditional vs. innovative industries), the large weight of manufacturing, and the important role of the state.

Italian companies of any size are generally controlled by an entrepreneurial family. Large companies are under the influence of a controlling shareholder, which is usually a family, the state, or a foreign multinational company.

The stock exchange and the financial markets play a limited role in the national economy. A number of large Italian companies prefer to remain private and to rely on retained earnings and banks loans to finance their growth plans.

The large massive privatization process started at the beginning of the 1990s could change the Italian capitalism, favoring the diffusion of widely held companies. However, lacking some preconditions, privatized companies are today under the influence of one or a coalition of controlling shareholders.

The Italian governance model of a joint-stock company includes several governance bodies. In addition to internal bodies, a number of actors (both from the private and the public sectors) play a governance role, by protecting private or public interests or increasing the efficiency of markets.

In Italy, senior management generally manages the company in the interest of the controlling shareholder, at the expense of those of the minority shareholders, when their interests diverge.