Informal External Institutions in the Italian Economy

Sociocultural Norms

International taxonomies of corporate governance list Italy, along with other continental European countries (e.g., France and Germany), within the insider-dominated or relationship-based corporate governance systems, in contrast to the outsider market-based systems that characterize the Anglo-American countries (La Porta, Lopez-de-Silanes, and Shleifer 1999 and Clarke 2007). Within relationship-based corporate systems Italy belongs to the Latin subgroup (together with France, Spain, etc.), in contrast with the Germanic subgroup (Germany, Switzerland, etc.), although it has its own individual features and does not fit completely into the international standard models (Melis 2000).

Trust, social relations and family are key sociocultural issues that characterize the Italian society as well as its corporate model. In Italy, most companies, including the largest nonfinancial listed ones, are heavily networked family firms. Networks, trust, and norms of reciprocity work to foment and build up relationships and alliances of companies and their controlling shareholders. Decision making is often done behind the scenes, among the in-group. Business meetings—including the meetings of the board of directors—are then used to ratify the decisions taken elsewhere and to communicate them to members who were not involved in the decision-making process. This was common even among listed companies, although regulation and the increased attention on transparency and corporate governance best practices are making these habits less frequent.

It is a naıve assumption that corporate objectives are culture-free. Senior executives in different countries have been found to have considerably different notions of the reasons for the existence of the firm and pursue different kinds of goals for their firms. On the one hand, U.S. executives strongly subscribe to shareholder value thinking, with the other stakeholders being secondary and representing means toward the end of producing shareholder value. On the other hand, German and Japanese executives do recognize that shareholders are important stakeholders, but are not in favor of a strong focus on them. They emphasize the importance of serving society and balancing the interests of shareholders, employees, and other stakeholders (Witt and Redding 2012).

In Italy, the concept of the firm lies somewhere between the instrumental Anglo-American view and the institutional German–Japanese view, but is altogether closer to the latter (Weimer and Pape 1999). Rather than being considered a “nexus of contracts,” in Italy the firm is usually conceived as an institution operating with a long-term horizon. Differently from the German–Japanese model, the influence of banks and employees is less institutionalized and relevant.

Regarding banks, Italy is the country among the G7 countries in which nonfinancial listed companies tend to use a higher proportion of total debt versus equity (McClure, Clayton, and Hofler 1999). However, while banks are important providers of both long-term and short-term debt capitals, they are not actively involved in the governance of non-financial listed firms and do not elect representatives on the board of directors (see Chapter 6 for the composition of the board of directors of Italian listed companies). As pointed out in Melis (2000), as long as a firm is able to refund its debts, the bank is neither involved in the corporate strategy’s formulation and implementation, nor considered as a partner for corporate strategy by the senior management. Employees and trade-unions are not usually actively involved in corporate governance and their negotiations with the top management tend to focus on working conditions and compensation. Even when they are able to exert some influence on corporate strategy, this happens often through an antagonistic behavior, rather than an actual involvement in corporate governance. This is a striking difference with the German model.

To sum it up, in Italy even firms going public tend to remain “private,” that is they are still under the control of a dominant blockholder (see Chapter 5 for the ownership and control structure among Italian nonfinancial listed companies). Although Italian senior managers usually claim to pursue shareholder value, this expression does not represent the same concept in Italy as in the Anglo-American corporate model. As a matter of fact, Italian senior managers seek to maximize the value for the dominant blockholder (Melis 2000).

In view of the reciprocal shareholdings, shareholders’ agreement, family ownership, and the overall stability of ownership structure over time (see Chapter 5), one can argue that long-term relationships are encouraged, rather than disfavored, by the prevailing sociocultural norms in the country (Weimer and Pape 1999).

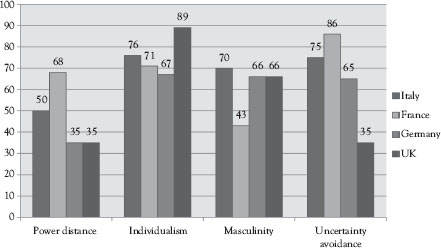

If we examine the Italian culture through the lens of the four dimensions of the Hofstede model, we can get a brief overview of the deep drivers of Italian culture relative to other main European countries: France, Germany, and the United Kingdom (see Figure 4.1).

Figure 4.1 A comparison of Italian, French, German, and British cultural values

Source: Our elaboration on Hofstede Centre data, available at http://geert-hofstede.com. Each scale runs from 0 to 100, with 50 as a mid-level value. If a score is under (over) 50 the culture scores relatively low (high) on that scale. For example, in the case of individualism—the low side (i.e., under 50) is considered “Collectivist” and above 50 considered “Individualist.” A country with a score of 43 would be collectivist but less collectivist than someone with 28 who is moving down toward the 0 mark.

Italian business culture is characterized by a relatively high power distance, when compared with Germany and the United Kingdom. Italians do expect differences in power between people, yet they are often cynical about persons in positions of authority. Offices in Italy are ruled by formality. Subordinates are rarely allowed to call their superiors by their first names. In the boardroom this is reflected in the great power given to the controlling shareholder who sits as CEO (and/or Chairman) despite owning sometimes only a relatively small fraction of equity (see Chapter 5). In other words, there is a generally accepted notion that some shareholders are more equal than others. “Shares are weighted, not counted” stated Enrico Cuccia, long-time head of the most important merchant bank in Italy, Mediobanca, implying that the shares owned by the in-group weighted more than those of the outsiders.

The more collective nature of Italy—when compared to the Anglo-American countries—can be interpreted in many ways. Italian businesses are primarily owned by families. Stock market capitalism, with its “buy and sell” approach to shareholding, is historically rooted in individualism.1 Such ownership traits have been found to be significantly correlated with the Hofstede’s Individualism Index. In this perceptive, the relatively moderate level of Individualism that characterizes Italian culture is reflected in a lack of dispersed ownership, and a consequent more stable ownership, even among the largest listed nonfinancial companies (Hofstede 2013). It is also reflected in the fact that business is preferably done with people with whom one is familiar. This preference finds its roots in what Banfield (1958) defined as “amoral familism,” that is the self-interested, family centric, society that is unable to act together for their common good, but acts for the sake of nepotism and the immediate family, and provides a conceptual key to understanding Italian cultural differences from the Calvinist’s culture that usually characterizes IN tHE ItALIAN ECoNoMY 59 Anglo-Saxon and Northern European countries. As for instance, Gabbioneta et al. (2013) argued that the close relationships and lack of social distance between Parmalat and its circle of gatekeepers seem to be illustrative, to a greater or lesser extent, of a national pattern of behavior. Another example is provided by the use of cross-shareholdings, in which there is an implicit agreement between close members that such shareholdings are not used to launch unwelcomed takeovers (Weimer and Pape 1999) (see also Chapter 5).

Italy is characterized by a high score in masculinity. This indicates that it is a highly success-oriented and driven society, with success being defined by the winner. This value system starts at school and continues throughout the professional experience within organizations. This seems to be reflected in the dominant role of the controlling shareholders, who may exercise their power even at the expenses of the interests of minority shareholders and other stakeholders (see Chapter 5). Italy is a paternalistic country with the father taking the authoritative role in family matters. This cultural trait has an influence even in family-controlled companies that are listed. An illustrative example of the role of family and culture is given by female representation on the board of directors. Female representation was traditionally very limited, even in listed companies (see Chapter 6). In addition, as reported by an empirical study by Bianco et al. (2015), the majority of female directors had a family connection (being his wife, daughter, sister, or close relative) with the controlling shareholder. This frequency of kinship is significantly lower among male directors, although differences are decreasing over time.

Italian culture is characterized by a high score on uncertainty avoidance, especially when compared to Anglo-American cultures. This cultural dimension reflects the way in which a society deals with the fact that the future is unknown. Rules and procedures are more necessary to have the perception to reduce uncertainty. Formality in Italian society is important and the Italian law (both penal and civil code) is complicated with clauses, codicils, and so on. However, there is an apparent contradiction between all the existing norms and procedures and the overall lack of compliance. This contradiction is only apparent as, in a highly bureaucratic country such as Italy, individuals—and firms—learn which rules are important and which are not, in order to survive the “red tape.” Within organizations, high uncertainty avoidance, and the consequent desire to minimize the level of performance risk that is present in compensation plans, results in less frequent adoption of variable, performance-related, compensation schemes for executives and employees (Tosi and Greckhamer 2004). Especially for the latter, a great weight is given to seniority-based compensation, in contrast with performance-based pay (see Chapter 7 on executive and director compensation).

News Media

Media can potentially play a key role in disciplining corporate decisions. The press can help to shape corporate governance in terms of board independence and investor protection (Dyck, Volchkova, and Zingales 2008; Joe, Louis, and Robinson 2009; Kuhnen and Niessen 2012), as media can affect directors’ reputation in many ways.

Negative media coverage can affect not only the reputation of directors vis-à-vis the shareholders, but also their reputation vis-à-vis their future employers and society at large. As pointed out by Dyck and Zingales (2002), such a threat can be highly effective, as “no insurance policy can protect a director from reputational penalties.” Directors prefer, in fact, to avoid criticism from the social or professional groups they belong to, even if such criticism does not involve any monetary losses for them (Bebchuk and Fried 2004).

The role and effectiveness of the media depends upon the characteristics of the institutional environment. According to a study by Dyck, Volchkova, and Zingales (2008), the impact of the media is likely to be more visible, although not necessarily more important, in institutional environments where executives and directors underestimate ex ante the degree of intervention and influence of the media, enforcement of investor protection is generally low, and corporate governance best practices are not generally well-established. This seems to be the case of Italy.

Italy is an outlier in European Union with its Partly Free status given by the Freedom House.2 Although freedom of the press in Italy IN tHE ItALIAN ECoNoMY 61 is constitutionally guaranteed and generally respected in practice, major concerns have been expressed regarding concentration of media ownership as well as Government attempts to interfere with editorial policy at state-run broadcast outlets.

Italy suffers from an unusually high concentration of media ownership by European standards. The 2004 so-named Gasparri Law on broadcasting has been heavily criticized for provisions that had enabled Prime Minister Berlusconi to maintain control of the private media market, largely through his ownership of the Mediaset Group. He is the main shareholder of Mediaset Group, which owns several national television channels, Mondadori, Italy’s largest magazine publisher, and Publitalia, the largest advertising company. In addition, his political position had permitted him to exert a strong influence on the State media (in particular the State broadcaster, RAI), including the appointment of directors and leading journalists. This was possible as the Parliament has direct control over the appointment of most directors and a number of key journalists in the national and state-owned broadcasting television. With the 2006 election of Romano Prodi as prime minister, overt Government interference in media content started to decrease. However, Berlusconi’s return to power in 2008 gave him an enormous influence over up to 90 percent of Italy’s broadcast media through the state-owned outlets and his own private media holdings. Berlusconi’s resignation from the premiership in 2011 limited, again, his influence over State media. This helped to reduce the concentration in the media industry de facto. However, also after this change, Berlusconi continues to have a high influence on the media industry as he still controls Mediaset and, thanks to its leadership in Forza Italia political party, can affect decisions in the national broadcasting.

The high concentration in the broadcast sector represents a concern for media freedom, as most Italians receive news and information through these media. The press industry has different ownership structures. There are many newspapers and news magazines, most of them with regional bases. National newspapers are primarily run by political parties or owned by large media groups, and they continue to provide a range of political opinions, including those that are critical of the Government. There is also an important economic influence over press content, as the more diffused and credible newspapers have relevant ownership links with the business sector: Il Sole 24 Ore, the most important Italian financial newspaper, is owned by the association of Italian entrepreneurs (Confindustria), Il Corriere della Sera—for a long time controlled by a coalition of shareholders including large industrial and financial groups—has been recently acquired by Cairo Communications (a family-owned group controlled by Urbano Cairo), la Repubblica controlled by l’Espresso (De Benedetti group), and la Stampa controlled by the Agnelli family have been recently merged, il Messaggero is controlled by Caltagirone, il Giornale by Berlusconi family, and so on.

Anecdotal evidence has been reported on how the lack of media independence has favored expropriations by trying to influence investors’ behavior (see Box 4.1).

Following the arguments of Dyck, Volchkova, and Zingales (2008), when compared to the United Kingdom or the United States, Italian top managers and directors work in an institutional environment where the media are used to report mostly what the business establishment wants. For this reason, they are less likely to factor into their decisions the reputational cost the media could inflict. Therefore, in a relationship-based corporate system, such as the Italian one, media could affect firms’ (and top managers’) reputation and compromise their relational capital. A study, conducted on a sample of Italian nonfinancial listed firms by Melis, Gaia, and Carta (2015), provides empirical evidence that media coverage on corporate governance issues may provide an incentive and influence firms’ strategic decisions. In particular, the study found that, during the global financial crisis, the extent of voluntary disclosure on directors’ compensation in firms’ annual reports was positively associated with the level of related media coverage on this issue.

Box 4.1 The Role of Media in Corporate Governance. The Case of Pirelli Restructuring

In November 2007 Pirelli’s board of directors proposed an operation that would have favored voting shareholders and harmed nonvoting shareholders by reducing their dividend privileges. The transaction needed the approval of the nonvoting shareholders’ meeting with a percentage of favorable votes equal to at least 20 percent of the non-voting shares.

The plan was approved also because some of the most important Italian media misled investors by reporting that operation was favorable to both classes of shares.

This episode questions the independence of newspapers from powerful business groups. Il Sole 24 Ore, the most important Italian financial daily, is owned by Confindustria, whose one of the most important members is Pirelli, while Il Corriere della Sera, the major Italian newspaper, was owned by a listed media company (RCS S.p.A.), which was controlled by a coalition of shareholders including Pirelli (with an approximately 5 percent of the votes) and five of the nine financial groups participating in the Pirelli shareholder agreement (i.e., Mediobanca, Fondiaria, Intesa Sanpaolo, Generali, and Sinpar).

Source: Bigelli and Mengoli (2011).

Corporate Governance Best Practices

Since 1999 a set of corporate governance practices, deemed as “best practices,” has been recommended for listed companies. What has been considered as “best practice” has been evolving over time and this led to several updates to the set of recommendations contained in different editions of the Italian Corporate Governance Code (1999, 2002, 2006, 2011, 2014, and 2015).

The adoption of these practices is voluntary under a “comply or explain” regime. Compliance to a specific recommendation is fully voluntary, while companies must explain the reasons why they do not comply with some recommendations. This is the capstone of the “comply-or-explain” system, which was “imported” from the U.K. corporate governance best practices.

The decision not to comply with some Code’s recommendations should necessarily not involve a negative evaluation, as it may be reasonable and contingent on several factors. First, the company may not have reached the structure that allows the full implementation of all recommendations (e.g., in case of a newly or small listed company). Second, the company may evaluate that some recommendations are less useful with its corporate governance model and/or may decide to implement alternative governance solutions, that is practices that differ from the noncomplied recommendation, if they can enable the company to reach its underlying objectives (Italian Corporate Governance Code 2015).

It is worth noting that there are no regulations about the content of those explanations, leaving current and potential shareholders to judge their appropriateness. This is in line with the E.U. Directive 2006/46/EC, which requires companies to publish a corporate governance report where they state whether they adopted a corporate governance code and provide information on its implementation. In other words, a company, which adheres to a corporate governance code and departs from some of its recommendations, must give detailed, specific, and concrete reasons for the deviation from the best practices. More specifically, for each case of noncompliance the Italian Corporate Governance Code (2015) recommends that firms should: (a) explain in what manner the company has departed from a recommendation; (b) describe the reasons for the departure, avoiding vague and formalistic expressions; (c) describe how the decision to depart from the recommendation was taken; (d) where the departure is limited in time and when the company envisages complying with a particular recommendation; (e) describe the measure taken as an alternative to the relevant noncomplied recommendation and explain how such alternative measure achieves the underlying objective of the recommendation or clarify how it contributes to good corporate governance. The latest version of the Italian Corporate Governance Code, issued in 2015, contains recommended best practices on the role of the board of directors and its composition and structure (including the recommended committees), the recommended best practices for the compensation design of executive and nonexecutive directors as well as other best practices concerning internal control (including statutory auditors’ role), risk management, and investors’ relations.

Best Practices on the Role of the Board of Directors

The Italian Corporate Governance Code includes recommendations on the role of the board of directors. The key principle is that directors should act and make decisions with full knowledge of the facts and autonomously pursuing shareholders’ value over a medium-long-term period (Principle 1.2). The emphasis placed on shareholder value seems to reflect internationally prevalent approach and is in conformity with Italian law, which considers the interest of the shareholders the point of reference for company’s directors.

The board of directors has the primary responsibility of formulating and pursuing the strategic objectives of the company (and the overall corporate group). In particular, in order to be effective and pursue long-term shareholders’ value, the board of directors is recommended by Italian Corporate Governance Code (2015: para 1.C.1) to:

(a) examine and approve the strategic, operational, and financial plans of the company and the whole corporate group, and monitor periodically its implementation;

(b) define the risk profile, both as to nature and level of risks, so that it is consistent with the company’s strategy;

(c) evaluate the adequacy of the organizational, administrative, and accounting structure of the company as well as of its strategically significant subsidiaries, in particular with regard to the internal control system and risk management;

(d) specify the frequency (in any case no less than once every three months), with which the delegated bodies (e.g., the CEO) must report to the board of directors on their activities;

(e) evaluate company’s performance, with a particular attention to the transactions to be carried out by the company (or its controlled subsidiaries) having a significant impact on the corporate strategy, profitability, assets and liabilities, or financial position; (f) perform, at least annually, an evaluation of the performance of the board of directors and its committees (including their size and composition), by taking into account the professional competence, experience, gender, and tenure of its members;

(g) taking into account the outcome of the board evaluation, report its view to shareholders on the professional profiles deemed appropriate for the composition of the board of directors;

(h) provide information in the corporate governance report on: (1) its composition, indicating for each member the qualification (executive, nonexecutive, independent), the relevant role held within the board, the main professional characteristics as well as time in office; (2) the number and average duration of board meetings (as well as of the meetings of the executive committee), and the related percentage of attendance of each director;

(i) adopt procedures for the internal handling and disclosure to third parties of information concerning the company, having special regard to price-sensitive information.

The Italian Corporate Governance Code also emphasizes the central role of the board and wants to avoid the risk that the CEO or the executive committee perform autonomously—for example, thanks to their inside knowledge or the link with the major shareholder—some of its functions. For this reason, it recommends that the appointment of one (or more) executive directors (or of an executive committee) should not relieve the board of directors of the above-mentioned tasks entrusted to it. In addition, the code clarifies that directors should take their role seriously and its effective performance requires an adequate time and commitment. So, directors are recommended to accept their position only when they deem that they can devote the necessary time to the diligent performance of their duties. This self-evaluation should take into account the commitment due to their own professional activity, the number of offices held as director (or statutory auditor) in other companies. On a yearly basis, the offices of director (or statutory auditor) held by the directors in other companies should be disclosed in the Annual Corporate Governance Report (para 1.C.2). Finally, the board of directors is recommended to issue guidelines regarding the maximum number of offices (as director or statutory auditor in other companies) that may be considered as compatible with an effective performance of a director’s duties. According to the Italian Corporate Governance Code (2015: para 1.C.3), this should be done by taking into account the commitment entailed by each role (executive, nonexecutive, or independent director), as well as the nature and size of the companies in which the offices are performed.

The chairperson plays an important role as s/he should favor the effective functioning of the board. In particular, the chairperson should ensure that adequate documentation is made available to directors (and statutory auditors) in a timely manner prior to the board meeting (Italian Corporate Governance Code 2015: para 1.C.5). Furthermore, s/he may invite the senior managers to attend a meeting of the board and to provide appropriate additional information on any items on the board meeting agenda (para 1.C.6).

Best Practices on the Composition of the Board of Directors

The composition of the board of directors represents a key issue in determining the effectiveness of the board. The Italian Corporate Governance Code (2015: para 2.P.1), in line with international best practices, recommends that boards should comprise both executive and nonexecutive directors, who should be adequately competent and professional. Nonexecutive directors are expected to bring their specific expertise to board discussions and to contribute to the adoption of fully informed decisions, paying particular care to the potential areas of conflicts of interest (Principle 2.1). The code does not establish a minimum number (or proportion) of nonexecutive directors on the board, but states a key principle according to which their number, competence, authority, and time availability should ensure that their judgment may have a significant impact on the board decision-making (Principle 2.3).

A key question in corporate governance practice (and theory) is whether the positions of chairperson and CEO should be separated or combined in one person. On the one hand, the argument is that separation, providing duality at the top of the company, enables a check and balance mechanism, limits the potentials for abuse, and provides the CEO to focus on managing the company, while the chairperson handles the running of the board of directors. This separation empowers the board of directors vis-à-vis the CEO, improving its monitoring role. The board has a clear leader—the chairperson—for whom its functioning is a priority (Tricker 2009). The two jobs also call for a different mix of abilities (Cadbury 2002).

On the other hand, the arguments in favor of combined roles are that a company needs just one leader, that spreading leadership duties between two people leads to conflict, weakens the CEO leadership, as well as it makes the line of accountability less defined (Lorsch and Zelleke 2005). Sir Adrian Cadbury himself, a strong supporter of the separation of the two roles, argued that the relationship between the chairperson and the CEO, where it fails to be productive, it can lead to major corporate problems (Cadbury 2002). As Lorsch and Zelleke (2005) summarize, “no compelling argument exists for splitting the chairman and CEO jobs,” despite most of the corporate governance codes in Europe do recommend it as a best practice.

On this point, the Italian Corporate Governance Code shares the U.K. best practices encouraging the separation of the two roles since the Cadbury report in 1992. As such, the Italian code supports the generally accepted key principle that “it is appropriate to avoid the concentration of corporate offices in one single person” (Principle 2.4). It shares the view that the roles of CEO and chairperson are different and that splitting the two positions may strengthen the impartiality that should characterize the role of the chairperson. However, the Italian Corporate Governance Code also remarks that a dual CEO may be valuable, in particular in small firms, for organizational needs. Therefore, where the board of directors has decided to delegate executive powers to the chairperson, it is not considered as a case of noncompliance. Hence, no explanation in the corporate governance report is required. However, in such a case, the Italian Corporate Governance Code (2015: para 2.P.5) recommends that companies disclose adequate information on the powers given to the chairperson.

When the roles of CEO and chairperson are concentrated in the same person, the board of directors should nominate an independent director as lead independent director.3 The lead independent director should enhance board independence in all the situations when it is potentially at risk (i.e., when there is a high concentration of power). It is a position with essential, but deliberately limited responsibilities. In particular, the lead independent director is expected to cooperate with the chairperson to guarantee that directors receive timely and complete information and should represent a reference for the requests (and contributions) of nonexecutive directors and, in particular, of those who are independent (Italian Corporate Governance Code 2015, para 2.C.4).

Best Practices on Independent Directors

The Italian Corporate Governance Code recommends companies to appoint an “adequate number” of nonexecutive directors who are independent. This recommendation is stricter for larger companies. In FTSEMIB index companies, at least one-third of the directors should be independent, in all other companies independent directors should be no less than two (see Italian Corporate Governance Code 2015, para 3.C.3).

While in widely held companies it is important to nominate directors that are independent from the executive directors (especially the CEO), when the ownership and control structure is concentrated, as in the large majority of Italian listed companies, the most important aspect is the independence from the controlling shareholder(s). Therefore, according to the Italian Corporate Governance Code (2015), a director may be defined as independent when s/he does not entertain, directly, indirectly, or on behalf of third parties, nor has s/he recently entertained, any business relationships, able to influence her/his autonomous judgment, with the company, its subsidiaries, the executive directors, or the controlling shareholder(s) (Principle 3.1).

In addition to this general definition, the Corporate Governance Code provides several examples of situations that are likely to affect director independence, such as:

s/he owns, either directly or indirectly or on behalf of third parties, an amount of shares enabling him/her to control the company, or is (or has been in the previous three financial years) able to exercise a dominant influence over the company, or participates in a shareholders’ agreement through which one or more persons can exercise a control or dominant influence over the company;

s/he receives, or has received in the previous three years, from either the company, one of its subsidiaries or the holding company, an amount of additional remuneration that is significant when compared to the fixed remuneration of other nonexecutive directors in the company;

s/he has been a director of the company for more than 9 years in the last 12 years;

s/he is an executive director in another company in which at least one of company’s executive directors holds a directorship (i.e., interlocking directorships);

s/he has close family ties with the company’s executive directors or with a person who is in the above-mentioned situations.

The above-mentioned examples are not nonexhaustive or binding. Directors’ independence is to be assessed by the board of directors after their appointment and, subsequently, on a yearly basis (Principle 3.2). The board of statutory auditors should evaluate the correct application of the assessment criteria and procedures adopted by the board of directors for evaluating the independence of its members (Italian Corporate Governance Code 2015, para 3.C.5).

In evaluating the independence of their directors, boards can adopt additional or different criteria to assess nonexecutive director independence. For example, boards can qualify a director as independent even though s/he is in one of the above-mentioned situations; on the other hand, they can assess that a director is not independent by considering additional, more-restrictive, criteria. In accord with the best practices recommended by the Italian Corporate Governance Code, the results of the assessments of the board should be disclosed in the corporate governance report (Principle 3.2).

Best Practices on Board Committees

The Italian Corporate Governance Code, in line with international best practice, recommends companies to appoint subcommittees (hereafter committees) that may perform some activities delegated by the board. The committees should regularly report the results of their activities to the board, as the board of directors as a whole remains responsible for the areas covered by the committees.

When appointed, committees should comprise at least three directors.4 Their activities, defined by the resolution of the board of directors, should be coordinated by a committee chairperson. In the performance of their duties, the committees should be given access to the necessary company’s information and functions, according to the procedures established by the board of directors, as well as they can avail themselves of external advisers. Adequate financial resources for the performance of their duties, within the limits of the budget approved by the board, should be provided. In the corporate governance report, as recommended by Italian Corporate Governance Code (2015, para 4.C.1), the firms should disclose adequate information on the establishment and composition of committees, their expected tasks, as well as the activity actually performed during the year, the number of meetings held, their average duration, and the relevant percentage of participation of each member.

The Italian Corporate Governance Code recommends the appointment of the following committees:

The nomination committee;

The compensation committee;

The control and risk committee (also called audit committee in the United Kingdom).

Best Practices on the Appointment of Directors

The board of directors should set up a nomination committee. As a best practice, the Italian Corporate Governance Code (2015) recommends that this committee should be composed of a majority of independent directors (Principle 5.1) and that its key tasks should be (para 5.C.1):

to express recommendations on the size and composition of the board of directors, also in terms of the professional skills necessary within the board as well as on the maximum number of offices held by a director;

to submit proposals for candidates for director’s positions in case of co-optation, should the replacement of independent directors be necessary.

The Corporate Governance Code pointed out that even in companies characterized by a high level of ownership concentration, as most Italian nonfinancial listed companies are (see Chapter 5), a nomination committee may perform a useful advisory role in the identification of the “best” composition of the board, identifying the professional figures whose presence may contribute to board effectiveness.

Best Practices on Executive Compensation

The board of directors should set up a compensation committee. In order to enhance the independence of the procedure that leads to the directors’ compensation, this committee should entirely be composed of independent directors. Moreover, to guarantee the presence of specific competencies, at least one member of the committee should have an adequate knowledge and experience in finance and/or compensation policies.5

To avoid conflicts of interest in determining executive compensation, no director should participate in meetings of the compensation committee in which proposals about his/her compensation are formulated to the board of directors (Italian Corporate Governance Code (2015, para 6.C.6). In addition, the Italian Corporate Governance Code (2015, 6.C.7) recommends compensation committees that, when an external compensation consultant is hired to obtain information on market standards for compensation policies, the committee should previously verify that the consultant is not in a position that might compromise its independence (e.g., the consultant provides services to the human resources department or senior management).

To perform its duties effectively, the Italian Corporate Governance Code (2015, 6.C.5) recommends that compensation committees should:

periodically evaluate the adequacy, overall consistency, and actual application of the compensation policy of directors and senior management and make proposals to the board of directors;

submit proposals to the board of directors for the compensation of executive directors as well as for the identification of performance objectives related to the variable component;

monitor the implementation of decisions adopted by the board of directors and verify, in particular, the actual achievement of performance objectives.

As a general principle, the Italian Corporate Governance Code (Principle 6.1) recommends that the compensation of directors (and senior managers) should be established in a sufficient amount to attract, retain, and motivate people with the professional skills necessary to successfully manage the company. In particular, the amount and design of the compensation of executive directors and senior managers should incentivize them to pursue long-term shareholder value. To this purpose, a significant part of their compensation should be linked to achieving specific performance objectives, possibly including also nonfinancial targets, defined in advance and consistent with the company’s compensation policy (Principle 6.2).

The board of directors should, upon proposal of the compensation committee, establish a policy for the compensation of directors and senior managers (Principle 6.4). As an aftermath of the global financial crisis and the international (and national) outrage over executive compensation, the Corporate Governance Code (2015, 6.C.1) has issued stricter recommendations about the compensation policy, which should be consistent with the criteria detailed as follows:

(a) The variable and the nonvariable components of executive compensation are properly balanced according to the company’s strategic objectives and risk management policy, taking into account the industry in which it operates and the nature of the business carried out;

(b) Upper limits for variable components should be established;

(c) The nonvariable component shall be sufficient to reward the director when the variable component was not delivered because of the failure to achieve the performance objectives predetermined by the board of directors;

(d) The performance objectives—that is, the financial performance and any other specific objectives to which the payment of variable components is linked to—should be predetermined, measurable, and linked to the long-term shareholder value;

(e) The payment of a significant portion of the variable component of the executive compensation should be deferred for an appropriate period of time. The amount of that portion and the length of that deferral should be consistent with the characteristics of the company’s business and associated risk profile;

(f) Contractual arrangements (e.g., claw-back provisions) should be provided to allow the company to reclaim, in whole or in part, the variable components of compensation paid (or due), as defined on the basis of data, which subsequently proved to be manifestly misstated;

(g) Termination payments should not exceed a fixed amount or fixed number of years of annual compensation and should not be paid if the termination is due to inadequate performance.

The Corporate Governance Code (2015: para 6.C.2) has also issued a specific recommendation on share-based compensation plans. In particular, it recommends that:

shares, options, and other rights granted to directors to buy shares or to be compensated on the basis of share price should have an average vesting period of at least three years;

the vesting period should be subject to predetermined and measurable performance criteria;

directors should retain a certain number of shares granted or purchased through the exercise of the option rights, until the end of their mandate.

Best Practices on Nonexecutive Directors’ Compensation

The compensation of nonexecutive directors, in particular those who are deemed as independent, is a controversial issue worldwide, regarding both the amount and the design of their compensation. Some scholars and practitioners—especially from the American perspective—argue that the pay-for-performance principles for rewarding executive directors are applicable to independent directors as well, so that their interests would be better aligned with those of shareholders (e.g., Brown 2007; Hambrick and Jackson 2000; Poster and Ullman 2006; Magnan, St-Onge, and Gélinas 2010) other scholars underline that a strong association between nonexecutive directors compensation and firm’s share value may affect their independent monitoring (e.g., Dalton and Daily 2001; Zattoni and Cuomo 2010; Mallin, Melis, and Gaia 2015).

Among these two contrasting views, the Italian Corporate Governance Code has chosen the second one. This decision is based on the idea that executive and independent directors are expected to perform different roles. On the one hand, top managers perform a “decision management” function, that is, they initiate strategic proposals and execute the decisions ratified by the board; on the other hand, independent directors perform a “decision control” function, which includes ratification of proposals formulated by managers and monitoring of their implementation by executives. From this perspective, a strong relationship between independent directors’ compensation and firm’s share price (e.g., via a share-based compensation plan) may create the perverse incentive for independent directors to compromise their monitoring task, for example colluding with executives in the financial reporting process (e.g., Ronen, Tzur, and Yaari 2006; Cullinan, Du, Jiang 2010).

In sum, the Italian Corporate Governance Code recommends companies that the compensation of their nonexecutive directors should not be—other than for a nonsignificant portion—linked to the company’s financial performance. Nonexecutive directors should not be beneficiaries of share-based compensation plans, unless it is so decided by the annual shareholders’ meeting, which shall also provide the relevant reasons (Italian Corporate Governance Code 2015, para 6.C.4). Their compensation should be, instead, based on the commitment required from each of them, also taking into account their possible participation in one or more board committees (Principle 6.2).

Best Practices on Internal Control and Risk Management System

The Corporate Governance Code recommends companies to adopt an internal control and risk management system consisting of “policies, procedures and organizational structures aimed at identifying, measuring, managing and monitoring the main risks” (Principle 7.P.1). The internal control and risk system should be integrated with the organizational and corporate governance framework adopted by the company and should take into account the best practices both at national and international level. Moreover, it should contribute to the management of the company, by promoting an informed decision-making process, and to ensuring the safeguarding of corporate assets, the efficiency and effectiveness of management procedures, the reliability of financial information and the compliance with laws and regulations, including company’s bylaws and internal procedures (Principle, 7.2).

An effective internal control and risk management system should involve several corporate bodies. First of all, the board of directors should provide strategic guidance and evaluation on the overall adequacy of the system, and should identify one or more directors in charge of the internal control and risk management system and set up a control and risk committee. In order to enhance the independence of the internal control and risk management system, the committee should entirely be composed of independent directors.6 At least one member of the committee is required to have an adequate experience in the area of accounting and finance (or risk management), to be assessed by the board of directors (Principle 7.4).

In accord with the Italian Corporate Governance Code (2015, para 7.C.1), the control and risk committee should give advice and make proposals to the board of directors in the following areas:

Definition of the guidelines of the internal control and risk management system;

Assessment of the adequacy of the internal control and risk management system;

Monitoring the work of the internal auditing staff;

Liaison with the external auditing firm.

The director who is in charge of the supervision of the internal control system should perform the following duties: (a) to identify the main business risks and submit them periodically to the review of the board of directors; (b) to monitor the adequacy, effectiveness, and efficiency of the internal control and risk system; (c) ask internal audit function to carry out specific reviews in some operational areas; and (d) to report to the control and risk committee or to the board of directors on major issues resulting from his/her activity (Italian Corporate Governance Code 2015, para 7.C.4).

The participation of the chairperson of the board of the statutory auditors at the control and risk committee’s meetings is recommended, and that one of other statutory auditors is allowed, in order to foster their cooperation and avoid potential conflicts due to their overlapping duties (para 7.C.3).

The Corporate Governance Code (2015, para 7.C.5) recommends that the person in charge of internal audit should:

check the adequacy and effective functioning of the internal control and risk management system, through an audit plan, to be approved by the board of directors;

not be responsible for any operational area and be subordinated to the board of directors, to prevent any potential interference with their independence of judgment;

have direct access to all useful information for the performance of its duties;

draft periodic reports containing adequate information on its own activity, on the company’s risk management process, and on the compliance with the management plans defined for risk mitigation;

prepare timely reports on particularly significant events;

submit the above reports and be accountable to the chairperson of the board of statutory auditors, the control and risk committee, and the board of directors, as well as to the director in charge of the internal control and risk management system.

Best Practices on Statutory Auditors

The board of statutory auditors is a typical Italian governance body elected by the shareholders. Its main tasks are to monitor the directors’ performance in the discharge of their duties, in terms of compliance of their acts and decisions with the law and the corporate bylaws and their observance of the so-called “principles of good administration.” The board of statutory auditors is also responsible for reviewing the adequacy of the company’s organizational structure for matters such as the internal control system, the administrative and accounting system, as well as the reliability of the latter in correctly representing any company’s transactions (Melis 2004).

According to the Corporate Governance Code, the statutory auditors should be qualified as independent and shall act with autonomy and independence also vis-à-vis the shareholders, which elected them (Principle 8.1). The independence of each statutory auditor should be evaluated by the board of statutory auditors on a yearly basis. As a best practice (Italian Corporate Governance Code 2015, para 8.C.1), the result of this process should be communicated to the board of directors and the public, via a press release as well as in the annual corporate governance report. Like directors, statutory auditors should accept the appointment only when they believe that can devote the necessary time to the diligent performance of their duties (para 8.C.2).

The Corporate Governance Code devotes attention also to avoid potential conflict of interests on the statutory auditors. For example, it tHE ItALIAN ECoNoMY 79 states that their compensation should be proportional to their commitment and role, and on the size and nature of business of the firm (para 8.C.3). In addition, statutory auditors who have an interest, either directly or on behalf of third parties, in a certain transaction of the company, should, timely and exhaustively, inform the other statutory auditors about the nature, the terms, origin, and extent of his/her interest (para 8.C.4).

The board of statutory auditors is only one of the governance bodies in charge of control activities. To guarantee an effective control, it should collaborate with other parties involved in control and risk management. In particular, in the performance of their activities, the statutory auditors may ask the internal audit function to make assessments on specific operating areas (or transactions) of the company (para 8.C.5). In addition, the board of statutory auditors and the control and risk committee should exchange material information on a timely basis for the performance of their respective duties (para 8.C.6).

Best Practices on Relations with Shareholders

The Italian Corporate Governance Code recognizes the importance of shareholders’ meetings and recommends companies to take initiatives aimed at promoting the broadest participation possible of the shareholders in the assembly meetings and making easier the exercise of the shareholders’ rights (Principle 9.1). In addition, all directors should attend assembly meetings, as they offer the opportunity to provide shareholders with information about the company’s past, present, and future activities and performance (para 9.C.2). To improve assembly effectiveness, the board of directors should propose to the approval of the shareholders’ meeting rules ensuring that the meeting is conducted in an orderly manner and effectively and, at the same time, guaranteeing that each shareholder may speak on matters on the agenda (para 9.C.3).

The board of directors should develop a continuing dialogue with the shareholders (including institutional investors) based on the recognition of their reciprocal roles (Principle 9.2). To this purpose, the board should designate a person—or create a corporate structure like an investor relations department—that would be responsible for managing the relationship with shareholders (para 9.C.1).

Social and family relations are key sociocultural issues that characterize the Italian society as well as its corporate model. Trust and norms of reciprocity strengthen business relationships and alliances of companies and controlling shareholders. Decision making is often done behind the scenes, and formal business meetings are used to ratify the decisions taken elsewhere.

Based on Hofstede’s model, Italian business culture is characterized by (i) a relatively high power distance, when compared with Germany and the United Kingdom as Italians do expect differences in power between people; (ii) a more collective nature—when compared to the Anglo-American countries—due to probably the large diffusion of family-owned companies; (iii) a high score in masculinity indicating a highly success-oriented and driven society; and (iv) a high score on uncertainty avoidance, especially when compared to Anglo-American cultures, producing complex rules and procedures.

Media can potentially play a key role in disciplining corporate decisions as they can affect directors’, top managers’, and controlling shareholders’ reputation. While freedom of the press in Italy is constitutionally guaranteed and generally respected in practice, major concerns regard the concentration of media ownership as well as Government attempts to interfere with editorial policy at state-run broadcast outlets.

Since 1999, a set of corporate governance best practices has been recommended for listed companies. The recommendations have been updated several times in alignment with international best practices. Following the U.K. experience, the adoption of corporate governance practices is based on a “comply or explain” regime.

The latest version of the Italian Corporate Governance Code, issued in 2015, contains recommended best practices on several governance mechanisms including: (i) the role, composition and structure (including committees) of the board of directors, (ii) the compensation design of executive and nonexecutive directors, (iii) internal control (including statutory auditors’ role), risk management and investors’ relations.

1 Hofstede (2004) argued that in the highly individualistic cultures, the relationship between the individual and the organization is “calculative.” This occurs both for the employees and for the shareholders. A “hire and fire” approach for the employees, but also a “buy and sell” approach for the shareholders is widely accepted. By contrast, it is often considered as either “immoral” or “indecent” in less individualistic cultures.

2 Italy has been consistently classified as Partly Free in the last decade, with a range that went from 31 to 34 in the period 2010–2014. See Freedom House (2014) Press Freedom Survey 2014; Available on: www.freedomhouse.org.

3 A lead independent director should be designated also in the event that the Chairperson position is held by the shareholder who controls the company. The boards of directors of the largest listed companies (i.e., FTSE-Mib index) are recommended to designate a lead independent director also when requested by the majority of independent directors. In case of noncompliance, an explanation is required to be reported in the corporate governance report. See Italian Corporate Governance Code (2015, para 2.C.3).

4 When the board of directors comprises less than eight members, committees may be made up of two directors only, provided that they are both independent. See Italian Corporate Governance Code (2015, para 4.C.1).

5 Alternatively, the Corporate Governance Code recommends that the compensation committee should be entirely composed of nonexecutive directors, the majority of whom independent; but the committee chairperson should be an independent director. See Italian Corporate Governance Code (2015, para 6.P.3).

6 Alternatively, the Corporate Governance Code recommends that the committee should be entirely composed of nonexecutive directors, the majority of whom independent; but the committee chairperson should be an independent director. However, if the company is controlled by another listed company, the committee should be made up exclusively of independent directors. See Italian Corporate Governance Code (2015), para 7.P.4.