Boards in the Italian Listed Companies

Corporate Governance Models

Since 2004, the Italian corporate law has allowed listed companies to choose between three different corporate governance models:

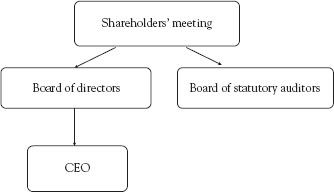

(a) The Italian “traditional” board structure, which had been the compulsory board structure for listed companies since 1882, a sort of “half-way house” between the American unitary board and the German two-tier board structure. It is composed of a board of directors (named Consiglio di Amministrazione) and a board of statutory auditors (named either Collegio sindacale or Collegio dei sindaci). Both boards are appointed at the shareholders’ general meeting and their term is usually three years (see Chapter 7 for an in-depth description of the nomination process). See Figure 6.1.

(b) A unitary board structure (named Consiglio di Amministrazione), with a compulsory audit committee (Comitato per il controllo interno) entirely composed of independent nonexecutive directors. This board model comes from the Anglo-American corporate practice and is expected to work similarly. The board of directors is appointed at the shareholders’ general meeting. Its term is usually three years.

(c) A German type of two-tier board structure, with a management committee (Consiglio di gestione) and a supervisory council (Consiglio di sorveglianza). The former is in charge with the daily management activities, the latter is involved in the most strategic transactions and the long-term industrial and financial plans of the company. This board model differs from the German structure as (i) there is no employee representation, and (ii) members of the management committee are not necessarily executives. The supervisory council is appointed by the shareholders’ general meeting, while the management committee is elected by the supervisory council, usually for a three-year period.

Despite the potential innovation in regulation, corporate practice has not changed much. Basically very few nonfinancial listed companies have changed their board structures since 2004. Empirical evidence shows that, at the end of 2015, all but a handful of Italian nonfinancial listed companies have adopted the “traditional” board structure (Assonime 2016). Therefore, in the remainder of the book, we will focus on companies with the “traditional” board model. As noted in Melis and Gaia (2011), the choice to maintain the “traditional” board structure is not necessarily due to the better fit of this board model compared to the two alternative models, but may be the result of path-dependence. Most of the firms might have chosen to maintain the traditional board structure with the board of statutory auditors not because it is more efficient than the two alternatives, but because it is the one they have always had and was in place at the time of the new law.

On the one hand, the board of directors is assigned strategic and governance tasks that are similar to those usually assigned to boards in Anglo-American firms (see Chapter 4); on the other hand, the traditional Italian board structure is unique in the oversight role it assigns to the board of statutory auditors. The board of statutory auditors is a unique Italian governance institution. Its main task is to monitor the directors’ performance in the discharge of their duties, with a task somehow similar to the Anglo-American independent nonexecutive directors. More specifically, the board of statutory auditors has the responsibility to check (a) the compliance of acts and decisions of the board of directors with the law and the corporate bylaws, and (b) the observance of the so-called “principles of business administration” by the executive directors and the board of directors. The board of statutory auditors has the duty (and the power) to report to the court any decision made by the board of directors that is against corporate interest, bylaws, and “principles of business administration.” Apart from the most serious irregularities (i.e., illegal decisions or in breach of corporate bylaws), the board of the statutory auditors is expected to monitor the board decision-making process rather than the decision itself. Statutory auditors should neither express their opinion about strategic corporate choices nor examine different options, draft proposals, and make recommendations for possible solutions. The board of statutory auditors is also responsible for reviewing the adequacy of the company’s organizational structure for matters such as the internal audit system, the administrative and accounting system, as well as the reliability of the latter in correctly representing any company’s transactions (see Melis 2004, for more information on the board of statutory auditors).

Figure 6.1 The prevailing boards structure in Italy

Board of Directors’ Composition

The board of directors is appointed by the shareholders’ general meeting, generally for a three-year term, and its composition is not “staggered” as all directors are usually appointed at the same Election Day.

The search for the “optimal” size of the board of directors has been the subject of much debate worldwide without a final answer. On the one hand, small boards tend to be easier to convene, require less effort to lead, and have a more relaxed, informal culture that leads to quicker decisions. On the other hand, larger boards may have the required range of expertise to govern a more complex organization. In Italian listed companies, the average board consists of 9 to 11 directors, a size that is considered balanced. As expected, board size increases with firm size: Assonime (2016) reported that top 40 FTSE companies have a larger board than other listed companies.

About board composition, boards include, on average, two to three executives, three to four nonexecutive and not independent directors, and four independent nonexecutive directors. In the last decade there has been a slight, but steady, increase in the presence of independent directors, who increased from 3.6 (35.4 percent of the board) in 2010 to 4 (40.5 percent of the board) in 2015 (Assonime 2014; 2016). In addition, in almost 40 percent of the boards of directors there is one (or, rarely, two) director(s) appointed by minority shareholders (Assonime 2016).

Board diversity has become a topic of active policymaking in many countries. Diversity can have both benefits and costs. Regardless of its effects, much of the work on boardroom diversity, both among policymakers and in the academia, has focused on gender diversity.1 However, it is not just gender that brings diversity into the boardroom. As noted by Ferreira (2010), board diversity comprises a variety of kinds of diversity, including task-related diversity (e.g., educational or functional background) and nontask-related diversity (e.g., gender, age, race, or nationality), as well as structural diversity (e.g., board independence). Board member diversity can have positive and negative effects on board performance. On the one hand, it brings unique perspectives that can enhance a board’s independence of thought so that the board can better perform its monitoring function as well as its advisory role. On the other hand, it may cause higher decision-making costs in boards and increase the likelihood of conflicts in teams (Ferreira 2010).

The annual survey of Assonime (2016) reports that the average age of directors in Italian listed firms is about 58 years. Executive directors are generally slightly younger (approximately 58 years old) when compared to independent directors (59 years). Their average time in office is almost five years. Tenure as a board member is usually longer for executive directors (seven years) than for nonexecutive directors (four years) and for independent directors (below four years).

The majority of directors are men (over 70 percent), although almost every board does comprise at least one woman as director. Gender diversity in Italian listed boards has been steadily increasing since the 2011 law mandated gender quotas (CONSOB 2015). According to the law, the members of the underrepresented gender should account for at least one-third of the board (one-fifth for the first term) (see Chapter 2). As a result, at the end of June 2015, women representation in Italian corporate boards reached 28 percent. While before this law, the great majority of the few female directors had a family connection with the controlling shareholder (Bianco, Ciavarella, and Signoretti 2015), now women are also included among independent directors.

Nonexecutive directors have usually a business background: the majority of them are senior managers or entrepreneurs in other companies, while academics and professionals (e.g., certified public accountants and lawyers) comprise approximately one-third of nonexecutive directors (Spencer Stuart 2016a).

The degree of board diversity varies according to the identity of the controlling shareholder (CONSOB 2015). Firms controlled by financial institutions generally have a younger and more educated board of directors, with a higher presence of foreigner directors. By contrast, boards in family-controlled firms are usually characterized by a lower presence of female and foreigner directors and have, on average, older members, with a lower educational background. Family directors have, on average, a weaker educational background than nonfamily board members.

Director interlocks has always been a common feature in Italy and evidence of “enlarged collusion,” that is collusion established through shareholdings and board interlocks among companies that do not necessarily operate in the same industry (Drago, Manestra, Santella 2011). A high percentage of Italian large listed companies are connected with each other mainly through a small number of directors. Such group of interlocking directors shows a remarkable stability over time with few entrants and few exits (mainly related to the passing away of the director). For this reason they have been defined as “the Lords of the Italian stock market” (Santella et al. 2010). However, in the most recent years the Assonime annual survey reports that director interlocks are becoming less common, at least in listed firms. The typical (i.e., median) director sits on one board, only 14 percent of directors hold multiple seats and the top 1 percent “most connected” directors hold between 4 and 6 directorships. However, listed firms with at least one interlocked director in their board still comprise over 60 percent of the total market capitalization (Assonime 2016; CONSOB 2015).

Board of Directors’ Structure

As illustrated in Chapter 4, the Italian Corporate Governance Code recommends companies to avoid the concentration of corporate offices in one single individual. In addition, companies should appoint a lead independent director when the chairperson of the board is either also the CEO of the company or a controlling shareholder. The underlying logic is the CEO should run the company, while a different person—the chairperson—should run the board to facilitate board effectiveness. In 2015, about one-third of the listed companies did not separate the positions of CEO and chairperson.2 In approximately 20 percent of the nonfinancial companies the controlling shareholder is also chairing the board. The full concentration of powers, that is having a controlling shareholder who is also the CEO and the chair of the board, is rare (i.e., it regards less than 10 percent of the listed companies) and decreasing over time (Assonime 2014; 2016). These situations are more common in smaller listed companies and extremely rare in the largest ones. In most of these situations, companies tend to appoint a lead independent director, as recommended by the Italian Corporate Governance Code (Assonime 2016).

However, the appointment of a lead independent director is not explicitly recommended when the chairperson is a member of the controlling family and companies may creatively comply with this recommendation in formal terms (see Box 6.1).

Box 6.1 Creative Compliance in the Choice of a Lead Independent Director. The Case of Davide Campari S.p.A

In 2008, Mr. Luca Garavoglia, the son of the controlling shareholder, Mrs Rosa Anna Magno Garavogliaw, was the chairperson of the company. He was also an important executive director, but was not qualified as CEO.

Hence, the company decided not to appoint a lead independent director “since the Chairman does not directly and personally control the Company” (Davide Campari S.p.A 2008, p. 12).

Source: Company proxy statements.

The average board of directors of a nonfinancial company meets 10 times a year for over two hours per meeting. Larger companies tend to meet more frequently and have longer meetings. Directors attend on average 90 percent of board meetings (Assonime 2016; CONSOB 2015).

In line with the recommendations of the Italian Corporate Governance Code and, more generally, with international best practices, the typical board of directors usually decides to set up committees. A greater use of committees stands out as one of the key changes in board structure since the issue of the corporate governance code. As illustrated in Chapter 4, the Italian Corporate governance Code recommends listed companies to set up three committees: an audit committee (usually named control and risk management committee to emphasize its risk management role after the global financial crisis), a compensation committee and, since 2011, a nomination committee. The members of such committees, when established, are appointed by the board of directors within its own directors.

A control and risk management committee has been established by the great majority of nonfinancial listed companies (over 90 percent) and this number is relatively stable over the last 10 years (Assonime 2015). With few exceptions, typically related to smaller listed companies, this committee is composed of three nonexecutive directors, among whom the majority is allegedly independent. In over 50 percent of the companies, this committee is entirely composed of independent directors and this practice is steadily becoming more widespread. In companies where minority shareholders appointed a director, this director sits on the control and risk committee in almost 80 percent of the cases. At least one member of the committee has financial and accounting knowledge (i.e., s/he is a financial expert) in approximately 90 percent of the cases. This practice has rapidly increased over time (from 65 percent in 2009 to 90 percent in 2013). On the other hand, in only about 10 percent of the companies that established a control and risk management committee a director appointed by minority shareholders sits on this committee. The average number of meetings is 6 to 7 per year in nonfinancial companies and each meeting’s length is, on average, almost two hours (Assonime 2016).

A compensation committee has been established in a wide majority of listed companies (Assonime 2016). The number of firms with this committee is slowly, but steadily growing (from approximately 80 percent in 2008 to almost 90 percent in 2015). It is usually composed of three nonexecutive directors; two of them are allegedly independent. Only in approximately 49 percent of the cases the compensation committee is entirely composed of independent directors; although this percentage is still relatively small, there is a growing pressure to converge to such a composition. In companies where minority shareholders appointed a director, this director sits on the compensation committee in over half of the cases. From an investor perspective, it is worth noting that the presence of an independent director appointed by minority shareholders has been found to have a positive influence on the design of executive stock-based compensation, while its absence often allows stock-options designs that lead to rent-extraction purposes (Melis, Carta, Gaia 2012). On average, the compensation committee meets three times a year in nonfinancial companies and each meeting lasts about an hour (Assonime 2016).

In 2015, approximately 46 percent of nonfinancial listed companies had a nomination committee. Although it is not as widespread as the control and risk management and compensation committees, this number represents a sharp increase when compared to the 15 percent of 2012 (Assonime 2016). Its increasing adoption has been stimulated by the 2011 revision of the Italian Corporate Governance Code that strongly encouraged listed companies to set up a nomination committee. Before this year, as the establishment of the nomination committee was not explicitly recommended, companies preferred to avoid setting up this committee claiming that it was not useful given the high level of concentration of the ownership and control structure (Melis, Gaia 2011). The average nomination committee is composed of either three (in nonfinancial firms) or four (in financial firms) nonexecutive directors; a majority of them is allegedly independent. In 2015, the average nomination committee held either two or three meetings in nonfinancial companies and each meeting’s length was, on average, approximately one hour (Assonime 2016).

Another key committee that is sometimes (approximately 11 percent) established by Italian boards, although not explicitly recommended by the Italian Corporate Governance Code, is the executive committee (Assonime 2016). Less common and, to some extent, less important than in the past,3 when established, the executive committee is usually entirely composed of executive directors and may have different functions, ranging from a direct involvement in business decisions to more limited roles. On average, it holds a monthly meeting that lasts about two hours.

Board of Statutory Auditors’ Composition

The board of statutory auditors is appointed by the shareholders’ general meeting. The Draghi reform (1998, Art. 148) required statutory auditors to comply with the “honor” and “professional” requirements set forth by the Italian Ministry of Justice, in agreement with the Ministry of Treasury and CONSOB (the Italian SEC). Candidates need to prove that their civil rights are not constrained (e.g., because of past fraudulent behavior) and should come from a pool of certified public accountants who have been involved in audit activities for at least three years (a minimum of one of the statutory auditors should comply with this condition), experienced senior managers, and academics in company-related subjects as specified in corporate bylaws. In addition, candidates should meet independence criteria. For example, those with close family ties with corporate directors as well as persons who work either in a self-employed capacity or as employees of the company cannot be elected as statutory auditors.

Since 1998 the composition of this board is not entirely up to the shareholders’ will. The Draghi reform (1998, Art. 148) has required listed companies to provide, in their corporate bylaws, the number of statutory auditors (not less than three), the number of alternates (not less than two), the criteria and procedures for appointing the chairman of the board of statutory auditors, and, last but not least, limits on the accumulation of positions. Ever more important, corporate bylaws shall ensure that minority shareholders are given the right—but not the duty—to present a slate and appoint one of the statutory auditors or, when the board of statutory auditors is composed by more than three members, two statutory auditors.

Over 90 percent of boards of statutory auditors are composed by three members, which is the minimum legal requirement. The great majority of statutory auditors are men, with women representing approximately 20 percent of the positions (see Assonime 2011), although women representation has been increasing over time, also thanks to the introduction of gender quotas in 2011 (see Chapter 2). Only few companies—mainly large nonfinancial corporations and banks—have a board of statutory auditors with a number that exceeds the legal requirement. In these cases, the board of statutory auditors is composed of five members (see Consob database at www.consob.it).

The 2015 Assonime annual survey reports that approximately 43 percent of listed companies have at least one member of the board of statutory auditors appointed from a slate presented by minority shareholders. This presence has been relatively stable over time and is significantly higher in larger companies. Over 80 percent of top 40 Italy’s FTSE companies have one statutory auditor appointed by minority shareholders.

The average statutory auditor in a nonfinancial listed company is 57 years old, with a tenure of 4.4 years (Assonime 2016). Although the average tenure is not particularly long, there are some cases (approximately 15 percent) in which the statutory auditor has been holding the office from more than nine years. This situation is considered “at risk” as it might impair the statutory auditor’s de facto independence.

The board of statutory auditors meets, on average, 10 times a year for over two-and-a-half hours per meeting (Assonime 2016). In addition, in respect to the law (see Art. 2045 of the Italian Civil Code) statutory auditors are mandated to take part to the meetings of the board of directors.

Boards’ Behaviors

The presence of a controlling shareholder, a common trait of Italian non-financial listed firms, is likely to be a curb to exercising boards’ activities (including those of the board of statutory auditors) effectively as this shareholder has a relevant stake in the company and tends to believe that s/he should be allowed to manage the company without too many constraints.

In Italy, the board of directors has traditionally had the role of “rubber stamping” decisions that were taken outside the board, either in the executive committee or within controlling shareholders’ private meetings (Melis 1999). The several law reforms and the corporate governance code have radically transformed board composition. Nowadays boards of Italian listed companies have a more balanced composition in terms of number of directors, presence of independent nonexecutive directors and diversity in terms of demographic and professional backgrounds.

In line with international best practices and a new concept of the role of the board of directors (see Chapter 4), board evaluation practices are becoming more widespread. The 2015 Assonime annual survey reported that almost 80 percent of the firms disclosed that they performed board evaluation activities. This happens more frequently in larger firms, preferably with the use of questionnaires, rather than interviews. Board evaluation usually takes into account size, composition, and functioning of boards and their committees. The appointment of external facilitators is not frequent and basically limited to larger firms. Only less than two-thirds of the companies that appointed an external consultant disclosed whether this consultant provided other services to the company, services that might impair its independence of judgment (Assonime 2016).

While the empirical evidence seems to highlight a transformation and an empowerment of the boards of directors, some commentators pointed out that there are still some important issues to overcome (Assonime 2014; Zattoni 2015). Some of the potential “red flags” in relation to international best practices are:

(a) The low presence of nomination committees, underlining the will of the controlling shareholder to decide who will sit in the board so to influence its decision-making;

(b) The standardization of annual corporate governance reports, suggesting a formal, rather than a substantial, respect of the recommendations of the corporate governance code, with a consequent potential minimal impact on board internal processes;

(c) The limited number of hours devoted to board activities,4 indicating the risk that boards still “rubber stamp” senior managers’ or controlling shareholders’ proposals, rather than carefully examine the issues before taking a decision;

(d) The possibility that independent directors respect formal requisites of independence, but are not able to express a powerful independent opinion in board discussions, which suggests that alleged independent directors are either not de facto independent or, at least, not active members of the board decision-making process;

(e) Board evaluation results are rarely disclosed to the market and, when this happens, it is in a synthetic, almost “boiler plate” form, suggesting that this practice may be adopted for legitimization, rather than efficiency, purposes.

Similar concerns are expressed regarding the effectiveness of the board of statutory auditors as a monitoring body. In the presence of a controlling shareholder, as noted by Melis (2004), the easier alternative for a statutory auditor seems to choose not to “rock the boat,” until necessary; and the board of statutory auditors seems to provide a legitimating device rather than a substantive monitoring mechanism.

Box 6.2 The Role of the Board of Statutory Auditors in the Parmalat Fraud

Often labeled as “European Enron,” Parmalat provides an excellent case of a deliberate massive accounting fraud (over €14 billion involved).

The board of statutory auditors was clearly unable to detect and report the fraud at Parmalat.

In his testimony in front of the Italian Parliament, Cardia (2004), the chairman of CONSOB at the time of the fraud, noted that the board of statutory auditors neither warned shareholders about what was happening at Parmalat, nor reported anything either to the court or to the Italian Securities and Exchange Commission.

Even when an institutional investor (Hermes Focus Asset Management Europe Ltd) formally asked the board of statutory auditors to investigate on some accounting issues, the board of statutory auditors responded by denying that any irregularity (“atypical and/or unusual related party or inter-company transaction”), either de facto or de jure, was happening.

Source: Melis (2005).

Statutory auditors are often more concerned with complying with formal requirements (in order to avoid any formal sanction), rather than on giving substantial information to shareholders. The majority of their reports contains set formulae and summary attestations. In cases of unusual or atypical transactions, there seems to be a lack of independent evaluation on the transaction’s economic reasons and consequences. In its report to shareholders, the board of statutory auditors often refers to information already provided by the management report. A case in point is provided by the Parmalat fraud (see Box 6.2).

More in general, the inefficiency of the board of statutory auditors as a monitor has been attributed to (Melis 2004):

(a) its lack of access to information related to shareholders’ activities. This kind of information would be very useful in monitoring the relationship between executive directors and the controlling shareholder. Anecdotal evidence shows that, instead of cooperating with the statutory auditors, CONSOB relies on their activity to monitor transactions that potentially involve conflicts of interest and eventually penalize them in case of “inadequate performance”;

(b) its lack of independence from the controlling shareholder. Their interest in being reappointed may be a deterrent to carrying out their duties in monitoring executive directors (who act as agents of the controlling shareholders) effectively, especially in the case of statutory auditors appointed from the slate presented by the controlling shareholder.

It is worth noting that there seems to be a lack of public evidence of higher efficiency in the monitoring done by statutory auditors appointed by the slates presented by minority shareholders.

Key Points to Remember

Despite the law allows three board models (including a unitary Anglo-American board structure and a German-like two-tier board structure, with a management committee and a supervisory council) almost all listed companies adopt the Italian traditional model composed of a board of directors (Consiglio di Amministrazione) and a board of statutory auditors (Collegio sindacale).

A typical Italian board of a listed company is made of 9 to 11 members: 2 to 3 executives, 3 to 4 nonexecutive and not independent directors, and 4 independent nonexecutive directors. The average age of directors is about 58 years. The tenure as board member is about seven years for executive directors and four years for nonexecutive directors. After the 2011 law mandated gender quotas, women representation in Italian corporate boards increased reaching 28 percent. About two-thirds of nonexecutive directors are senior managers or entrepreneurs in other companies, while the remaining are academics and professionals. The typical director sits on one board, only few directors hold multiple seats and the top 1 percent “most connected” directors hold between 4 and 6 directorships.

The concentration of powers of CEO and chairman of the board is rare and, in most of these cases, companies tend to appoint a lead independent director. Over 90 percent of nonfinancial listed companies have a control and risk management committee, usually composed by three nonexecutive directors, two of whom are independent and at least one has financial and accounting knowledge. Almost 90 percent of listed companies have a compensation committee, usually composed by three nonexecutive directors, two of them are independent. Almost half of the listed companies have a nomination committee, usually composed by three or four nonexecutive directors, a majority is independent.

The average board of directors of a nonfinancial company meets 10 times a year for over two hours per meeting. Almost 80 percent of listed firms perform a board evaluation, preferably with the use of questionnaires rather than interviews. However, the appointment of external facilitators is not frequent and basically limited to larger firms.

Over 90 percent of boards of statutory auditors are composed by three members, few of them have five members. About half of the listed companies have at least one member of the board of statutory auditors appointed from a slate presented by minority shareholders. The average statutory auditor is 57 years old and has a tenure of 4.4 years. The board of statutory auditors meets, on average, 10 times a year for over two-and-a-half hours per meeting.

While the empirical evidence seems to highlight a transformation and an empowerment of the boards of directors, there are still some important issues to overcome, for example, the low presence of nomination committees, the standardization of corporate governance reports, the limited time devoted to board activities, the prevalence of the form over the substance (e.g., directors’ independence, board evaluation).

1 Ferreira (2015: 110) concluded that “current research does not really support a business case for board gender quotas. But it does not provide a case against quotas either. … I do not think that the lack of evidence that female board representation improves profitability is a problem. The business case is a bad idea anyway. When discussing policies that promote women in business, it is better to focus on potential benefits to society that go far beyond narrow measures of firm profitability.”

2 When examining this issue from an investor perspective, it should be taken into account that the chairperson and CEO positions are often separated; in the majority of these cases some executive powers are delegated to the former.

3 Empirical studies in the 1990s (e.g., Molteni 1997; Melis 1999) reported that boards of directors often established an executive committee that tended to absorb most of the key functions of the board of directors, leaving the board to “rubberstamp” pre-agreed decisions.

4 For example, an empirical study reported that independent directors on Italian nonfinancial firms usually exert less effort than their counterparts in similar (in terms of size and industry) U.K. firms. See Mallin, Melis, Gaia (2015).