Ownership and Control in the Italian Listed Companies

Ownership Concentration and the Role of Dominant Shareholders

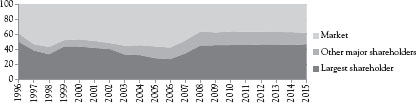

Despite the evolution of corporate law and corporate governance, and the consequent increase in the protection of minority shareholders’ rights (see Chapter 2), the ownership structure of Italian listed firms is still highly concentrated, in line with that of other major continental European firms (Zattoni and Mosca 2012). At the end of 2015, the first shareholder owns approximately 47 percent of the ordinary share capital with voting rights of all the companies listed at the Italian Stock Exchange, and this figure is substantially in line with those recorded in the previous five years (see Figure 5.1). Other relevant shareholders hold approximately 15 percent of the ordinary share capital with voting rights. This represents a relatively stable value compared to the previous recent years, but an increase compared to late 1990s. The market—that is, shareholders who individually own less than the 2 percent disclosure threshold—owns the remaining 38 percent of the capital. This figure has remained constant over the last five years, but has slightly decreased since late 1990s (see Figure 5.1).

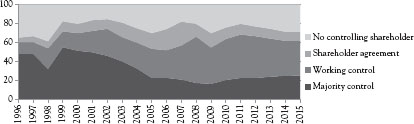

At the end of 2015, the control of Italian listed firms is still in the hands of wealthy entrepreneurial families, who are the “ultimate” controlling shareholders of more than the 60 percent of the market value of the ordinary share capital of all firms listed at the Italian Stock Exchange. State and local authorities control only 8 percent of the listed firms; however, among those there are some of the largest ones (e.g., ENI, ENEL, and Leonardo) as they represent almost one-third of the total market capitalization. Overall, over 85 percent of the share capital of listed firms is under the control of a single shareholder (or a group of shareholders via a shareholders’ agreement), either de jure (i.e., holding more than half of the ordinary shares) or de facto (i.e., owning less than 50 percent of the ordinary shares) (see Figure 5.2). Firms with a concentrated control structure comprise over 70 percent of the total capitalization of the market and represent almost the entire population of Italian nonfinancial listed firms. Ownership structure of financial listed firms is more dispersed, and half of them do not have a controlling shareholder.

Figure 5.1 The evolution of the ownership structure of Italian listed firms

Source: Elaborated from CoNSoB ownership database. data updated at december 31, 2015. 100 80 60 40 20

Figure 5.2 The evolution of the control structure of Italian listed firms

Source: Elaborated from CoNSoB ownership database. data updated at december 31, 2015.

At the end of 2015, CONSOB (2016) reports a steady and increasing presence of institutional investors in the ownership of Italian listed companies, being “significant” shareholders (i.e., holding a financial stake of at least 2 percent). This overall trend combines two different trends related, respectively, to Italian and foreign institutional investors, with the former slightly decreasing in presence while the latter marking an opposite trend. The role of institutional investors is, however, by no means comparable to the Anglo-American experience, as in Italy their shareholdings are still very limited at the firm level and their influence at the annual shareholders meeting is still low. Contrary to this tradition of passive shareholders, institutional investors are becoming more and more active in the most recent years. They collectively represented 20 percent of the share capital at the 2015 Annual General Meetings (AGMs), an important increase if compared to 13 percent in 2012 (see CONSOB 2015).

To sum it up, ownership structure in nonfinancial listed firms is relatively concentrated and their control structure is usually characterized by the dominance of a main shareholder, named “azionista di riferimento.” This blockholder—often a family or a coalition of families—is not a passive investor, but an active owner, that in most of the cases is able to monitor effectively and to influence executives in accord to its own interests. Executive directors and senior managers are usually accountable to this blockholder. In some cases, large blockholders appoint themselves as executive directors in the board (see Chapter 7).

Since Berle and Means (1932) pioneering study, we know that Anglo-American listed firms have a dispersed ownership and that in these circumstances there is a separation between ownership and control that may lead to an agency problem between shareholders and senior managers. In such widely held firms, the key corporate governance concern is how to make top managers accountable to shareholders.

The presence of a large blockholder reduces (or, sometimes, eliminates) the agency problem that arises between executive directors and shareholders. However, at the same time, it gives rise to another agency problem, the one between the controlling shareholder(s) and the minority shareholders.1 This second agency problem is likely to happen when the large blockholder is an individual or a family, as it is often the case in Italy.2 “Weak managers, strong blockholders and unprotected minority shareholders” have historically summarized the key corporate governance issues in Italian nonfinancial listed firms (Melis 2000). Although in the last 15 years corporate governance reforms have strengthened the level of protection for minority shareholders, large blockholders still tend to wield their power over Italian listed firms.

Control Enhancement Mechanisms

Control-enhancing mechanisms (CEMs) are corporate governance devices, widely used in continental Europe, including Italy. They allow controlling shareholders to increase their power over the company without incurring their “fair” share of the investment.

A report financed by the European Commission pointed out that approximately 44 percent (out of a sample of 464) European firms have one or more CEMs (Institutional Shareholder Services 2007). CONSOB (2016) reports that approximately 20 percent of Italian listed firms, whose market value accounts for 30 percent of the overall capitalization, adopt CEMs. Both studies also indicate that these mechanisms are more frequently adopted by large firms.

One basic principle of corporate governance is the proportionality between economic risk and control. In other words, the share capital that has an unlimited right to participate in the profits (and losses) of a firm (or in the residue on liquidation) should be able to exercise control over a firm in proportion to the risk carried. A pure application of this principle leads to a situation where any shareholder owns the same fraction of cash flow rights and control rights.

CEMs enable a shareholder’s controlling stake to exceed its ownership (and risk-bearing) stake by allowing a deviation from proportionality between ownership (i.e., residual income) rights and control (i.e., voting) rights. These deviations from the proportionality principle come in different guises and affect the dynamics of control allocation as well as the agency problems between shareholders and those entrusted with managing the firm (Burkart and Lee 2008).

There are many types of CEMs, and, in one form or another, they exist in all corporate governance systems around the world. These mechanisms can be classified into three main categories (Institutional Shareholder Services 2007; Bennedsen, and Nielsen 2010):

– Mechanisms allowing a blockholder to enhance control over the firm by leveraging voting power, (e.g., shares with multiple voting rights, preference shares, and pyramidal structures);

– Mechanisms used by a blockholder to lock-in control of a firm (e.g., voting right ceilings, share transfer restrictions, and supermajority provisions);

– Other mechanisms not included in the previous two classes (e.g., partnerships limited by shares, golden shares, cross-shareholdings, and shareholders’ agreements).

Hereafter we will provide a brief description of the characteristics of the CEMs that are more widely used among Italian listed firms: pyramidal groups, (nonvoting) preference shares, shareholders’ agreements, voting right ceilings, and priority golden share. It is worth noting that each CEM should not be analyzed in isolation, as CEMs are often strictly connected to one another, that is they constitute “a system whose aim is to allow the main shareholder of the holding company to maintain the control of a large amount of assets” (Zattoni 1999).

(i) Pyramidal groups. They are groups of companies where a holding company (usually controlled by either a family or a group of shareholders) controls a subholding that in turn holds a controlling stake in another subholding, and so on, until the final levels represented by the operating companies. This process can be repeated a number of times and may involve also listed firms. This CEM allows a shareholder (or a group of shareholders) to control one or more companies with a limited capital investment. The ratio between the amount of resources controlled and the own capital invested to maintain the control is maximized by creating several vertical levels. The higher the number of companies vertically controlling each other along the pyramid, the higher will be the degree of deviation from the proportionality between ownership and control.

To understand this mechanism, imagine that a holding company A owns 51 percent of company B, which in turn owns 51 percent of company C. The shareholder (or group of shareholders) that controls firm A is also able to maintain control over firm C even though its direct stake in C is nil. This three-tier pyramid enables the controlling shareholder of the holding company to control the company at the bottom with merely 12.5 percent of its cash flow rights. To reach this purpose, the controlling shareholder should hold a majority stake in the holding company that owns a majority stake in the subholding, which, in turn, owns a majority stake in the company at the bottom. By chaining more firms, the separation between cash flow rights and voting rights can be substantially increased without losing control over the whole group of firms in the pyramid. The number of levels and the ratio of shares owned by the holding company in the companies belonging to the pyramid group usually depend on the amount of funds made available by the controlling shareholder on the one hand, and, on the other, on the funds needed to pursue the development and the competitive advantage of the firms belonging to the group (Zattoni 1999).

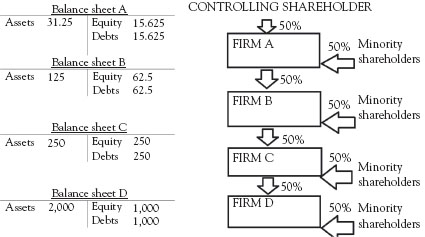

Zattoni and Cuomo (2016) reported that the proportion of Italian nonfinancial listed firms controlled via a pyramidal group has decreased over time, even though this CEM is still widely used in Italy. At the end of 2015, approximately 25 percent of Italian listed firms, representing over two-thirds of total market capitalization, belonged to pyramidal groups (CONSOB 2016). Figure 5.3 shows an exemplary, yet simplified, case of a pyramidal group in Italy.

To amplify the separation between ownership and control, the controlling shareholder can decide to list several companies of the group to collect additional funds for its development without losing the control, as the selling of the shares to other investors does not usually involve those that are necessary to control the firm. During the past decades large Italian corporate groups listed many subsidiaries, especially during the peaks of the stock market. In the last decade this mechanism is much less widely used as the evolution of the Agnelli group in the period 1985 to 2005 shows (see Box 5.1).

Another tool that amplifies the separation between voting and cash flow rights within pyramidal groups is the use of debts for financing the investments. A high debt-to-equity ratio is not a CEM. However, as noted by Zattoni (1999), the financial debt can amplify the effects of CEMs when it is used instead of issuing new shares. By increasing the debt, controlling shareholders are able to finance all the required investments of the firm and, at the same time, to maintain the control of the firm, as creditor (usually banks) do not intervene in the control of the firm as long as the firm is able to pay-back its debt. Figure 5.4 shows an example of a controlling shareholder who is able to control corporate assets worth €2,000,000 with an investment only €7,813 by combining a pyramidal group with the use of debt.

Figure 5.3 Simplified pyramidal structure of the Benetton group in 2009

Note: Listed firms are in bold.

Box 5.1 The Evolution of the Agnelli Group in the Period 1985 to 2005

The Agnelli family is one the wealthiest families in Italy and its group has been historically the most important private group in the country.

In 1985 the Agnelli family controlled Fiat S.p.A. through two listed holding companies, IFI and IFIL. These holding companies were controlled by the Giovanni Agnelli and C. S.A.p.A., a limited partnership formed by descendants of the founder. The Agnelli group controlled a total of 19 listed firms on the Italian Stock Exchange. The family controlled such a large and diversified amount of assets, thanks to the use of CEMs, and particularly of pyramids and saving shares.

Ten years later, in 1995, the Agnelli group became more complex and diversified. The Agnelli family controlled a total of 22 companies listed on the Italian Stock Exchange. Then, between 1995 and 2000, the Agnelli group started to simplify its structure and accelerated the process of simplification since 1998, when the Draghi law was enacted. As a result of this process, in 2000, Agnelli family controlled six listed companies.

In the following years, the process of simplification of the group structure continued. In 2005, the Agnelli group had a simpler structure than in 2000 and controlled only four listed companies.

Source: Cuomo, Zattoni, and Valentini (2012).

(ii) Preference shares. They are shares with limited (or even no) voting rights issued with special cash-flow rights to compensate for the lack of (full) voting rights. Italian listed companies have used traditionally two limited voting shares, the preferred shares (azioni privilegiate), that allow shareholders to vote in extraordinary meetings, and the saving shares (azioni di risparmio) that do not give voting rights to their holders These shares have limited (or no) voting rights, except at general meetings whose agenda directly affects their interests as shareholders (e.g., to approve mergers, the conversion of savings shares into ordinary shares), but receive a higher dividend. Additionally, these preference shares have priority over ordinary shares in case of liquidation of the firm. In order to avoid increasing too much the separation between ownership and control, Italian law states that limited or nonvoting shares may not represent more than 50 percent of the share capital. These types of shares were introduced in the mid 1970s and remained a relatively common CEM in Italy until the 1990s. However, their use has significantly decreased over time: Consob (2016) reported that approximately 10 percent of Italian listed firms use this CEM at the end of 2015. This figure is in sharp contrast with the 32 percent in 1998 and the 37 percent in 1992. As reported by different empirical studies (e.g., Bianchi and Bianco 2006; Mengoli, Pazzaglia, and Sapienza 2009; Bigelli, Mehrotra, and Rau 2011), the decline of their use appears to be related to the Draghi Law, which discouraged their use, as well as to the lack of appreciation by international institutional investors. For example, in 1998, five years before the accounting scandal emerged, Parmalat had to cancel a US$ 600 million nonvoting shares issue targeting US investors due to an adverse market reaction.3 Notwithstanding the dividend priority and protection, nonvoting shares in Italy have traditionally traded at large discounts to voting shares. An empirical study conducted on a sample of Italian nonfinancial listed firms found that ordinary shares were traded with a large premium (82 percent), when compared to nonvoting shares (see Zingales 1994).

Figure 5.4 The combination of a pyramidal group and the use of debt as control-enhancing mechanisms

Note: Legend: Amounts in thousands.

(iii) Shareholders agreements. They are explicit agreements among shareholders used by the largest shareholders when their individual financial stake does not allow them to control a firm. Shareholders agreements are so organized, especially at the holding company level, to stabilize the controlling position of the majority shareholder. Shareholders agreements may involve the use of the voting rights or the sale of the shares. Agreements involving votes have a mandatory consultation prior to each shareholder’s general meeting to decide on votes orientation; the final effect is that members of the syndicate vote together and so exercise a control over the firm. Blocking agreements imply, instead, that members of the pact cannot sell their syndicated shares to subjects that do not belong to the pact. In contrast to U.K. voting trusts, Italian shareholders’ agreements do not require the transfer of shares (or voting certificates) to a trustee for a determined period, but usually bind their members to some actions related to the vote in the assembly meeting or the sale of the shares (Gianfrate 2007). The diffusion of shareholders’ agreements among Italian listed firms has broadly held steady over the last decade (see Chapter 2). The case illustrated in Box 5.2 shows how shareholders’ agreements in Italy find their rationale on power and networking.

(iv) Voting right ceilings. These ceilings prohibit shareholders from voting above a certain threshold irrespective of the number of shares they hold. They are expressed as a percentage of the number of shares (or votes) during the shareholders meeting. They are meant to prevent the larger shareholder from controlling the decision-making process as a result of absenteeism at the annual general meeting. For example, Snam Rete Gas and Terna—firms in which the Italian State is the main shareholder—set a fixed voting ceiling of 15 percent (Snam Rete Gas) and 5 percent (Terna) of all outstanding votes, respectively.

Box 5.2 The Case of the Seat Pagine Gialle Shareholders’ Agreement

During the decade 2003 to 2012, Seat Pagine Gialle S.p.A. has been controlled via a shareholders’ agreement, which involved 49.56 percent of the voting capital. The following parties were involved in the agreement: (a) Alfieri Associated Investors Servicos de Consultoria S.A. (which owned 7.01 percent via AI Sub Silver S.A and PG Sub Silver B S.A.); (b) CVC Silver Nominee Limited (which owned 29.41 percent via Sterling Sub Holdings S.A. and PG Sub Silver A S.A.); and (c) the Permira investors (who owned 13.14 percent via Subcart S.A. and Subtarc S.A.).

This agreement regulated the appointment of directors, the functioning of the board of directors and the voting during shareholders’ meetings.

The participants agreed about the number (11) of directors in the board. Each participant to the agreement had the right to appoint two directors and to propose one candidate for the positions of CEO and chairperson, respectively. The candidate who received the support of at least two of the three participants was to be appointed as CEO (or chairperson). Two seats were reserved for the candidates designated by minority shareholders. At least two participants jointly appointed the remaining director (three, if minority shareholders did not propose any candidate), who was (were) to be chosen among the candidates that meet the independence criteria.

Board of directors’ resolutions on strategic topics (such as nomination/revocation of directors/managers; their compensation; corporate restructuring, etc.) needed the approval of at least four out of the six directors appointed individually by each participant.

Participants made a commitment that specific shareholders’ meeting resolutions (e.g., appointment/revocation of statutory/external auditors; modification of the company bylaws) should not be passed without the favorable vote of at least two out of the three participants.

All participants had the same voting rights within the agreement, regardless of the amount of shares each of them owned.

Source: Company’s proxy statements.

(v) Priority (“Golden”) shares. These shares grant their holders (typically the Government) specific powers of decision or veto rights in a firm, irrespective of the proportion of their equity stake. The Italian Privatization Law (see Chapter 1) allowed the Government to include some special rights in the articles of the corporate bylaws of “strategic” privatized firms. These rights can only be used in order to protect the “vital interests of the State.” In the largest Italian privatized firms, for example ENEL (Utilities), ENI (Oil and Gas), Finmeccanica (Industrials), and Telecom Italia (Telecommunications), the Italian Government maintains special rights, such as the vetoing of decisions to dissolve the firm, to split it up, to transfer its registered office, and to modify these special rights in the corporate bylaws. In ENEL, ENI, and Finmeccanica, the Ministry of Finance also has the right to appoint one board member without consulting the shareholders. However, until now, the Ministry has never exercised this special right.

(vi) Cross-shareholdings. A cross-shareholding, or reciprocal shareholding, is a situation where firm A holds a financial stake in firm B which, in turn, holds a financial stake in firm A. Cross-shareholdings may also be circular. For example, firm A has shares in firm B, firm B in firm C, and firm C in firm A. In Italy, these CEMs are less used as the law suspends the voting rights when a 2 (up to a 5, in specific circumstances) percent threshold is crossed. More specifically, when a listed firm holds more than 2 percent of another listed firm’s voting shares, the latter may not exercise the voting rights attached to shares exceeding 2 percent of the voting rights in the former and must sell such shares. After the 1998 Draghi reform, the limit on cross-holdings between listed firms has been raised to 5 percent upon the condition that the shareholders’ general meetings of the two firms give their consent.

The list of CEMs described previously is not comprehensive. Less widely used CEMs, at least among Italian listed firms, include, for example, the recently introduced “loyalty” shares that give the holder additional voting right after a certain holding period (see Chapter 3).

Overall, investors globally perceive CEMs as something negative (Institutional Shareholder Services 2007). For this reason, two empirical studies in Italy found that the increase in the protection of investors’ rights due to corporate governance reforms is associated with a decrease in the use of CEMs and in the separation between control and cash flow rights. However, their impact on ownership structure is less important and “control remains in the hands of the ultimate owner even post-reforms” (Mengoli, Pazzaglia, and Sapienza, 2009; Cuomo, Zattoni, and Valentini 2012).

Policymakers could address the concerns raised by the use of CEMs by either banning them or by providing increased disclosure. As the first option may have some detrimental effects on innovative potential of fast-growing listed firms,4 making disclosure requirements for CEMs is the preferred option in Italy and elsewhere (see Chapter 2).

Minority Shareholders’ Protection and Activism

Shareholders of Italian listed firms have traditionally held much greater collective power than their U.S. counterparts. Shareholders’ general meetings have always decided on a broad set of matters, including dividend policy, total compensation of the board of directors, and issues of shares. Insulation from shareholders has always been hard to achieve for executives, whom shareholders could (and still can) remove at will at the general meeting. However, due to the highly concentrated ownership such greater power has long been de facto useful only to controlling blockholders, allowing them to effectively align or monitor senior management.

Legal scholars (e.g., Belcredi and Enriques 2015) have pointed out that the legal environment can affect shareholder activism along three main dimensions:

– It may (or may not) empower investors by granting them broad (or narrow) governance rights and by making their exercise easy (or difficult) and inexpensive (or costly);

– It may (or may not) favor profitable stake-building, by allowing investors to do so in a stealthy way or by imposing disclosure of their stake early on;

– It may (or may not) grant investors bargaining leverage vis-à-vis corporate insiders (e.g., controlling blockholders), mainly by making it more (or less) easy to organize campaigns aimed at forcing change.

Italy has historically had all the traits of an unfavorable institutional environment for shareholder activism: concentrated ownership, inadequate legal protection for minority shareholders, and a noticeable disregard for their interests by controlling shareholders. However, corporate governance reforms enacted between 1992 and 2012 made this picture partially outdated. Although ownership structure is still highly concentrated and controlling blockholders still tend to consider minority shareholders’ interests as a constrain, investor protection has increased remarkably. As illustrated in Chapter 2, during the last two decades Italy’s corporate law has given minority shareholders a number of “voice” powers in order to protect their interests and counterbalance the power of the controlling shareholders and their “loyal” executives. As a consequence, minority shareholders (more specifically institutional investors) have, in several instances, become active at the institutional level, by lobbying Italian policymakers to improve corporate governance, as well as at the firm level, by influencing corporate decisions to avoid expropriation by the controlling shareholder (Belcredi and Enriques 2015).

More specifically, in 1994, the association of Italian asset managers (Assogestioni) set up a committee composed of executives of its main associates to act as a “watchdog of ethical behavior in the market” and “to monitor transparency and fairness of corporate transactions.” This committee pushed Italian policymakers and listed firms to improve disclosure on issues such as (i) the timing (and quality) of interim financial statements and (ii) tapping the market for increases in equity. In the following years, Assogestioni became a main actor in the corporate governance debate in Italy (Assogestioni 1996) and its lobbying activity was rather effective. Proposals such as mandatory slate voting for corporate elections have become law provisions. Assogestioni has also participated to the Corporate Governance Committee that prepared the Italian Corporate Governance Code (see Chapter 4). In 2004, Assogestioni decided to exercise its pressure directly at firm level by buying a few shares in each Italian top listed firm so that its representatives could intervene directly at the annual shareholders’ meetings. In each of these meetings Assogestioni’s representatives urged boards of directors to take investor-friendly measures concerning slate voting (which became compulsory for all listed firms in 2007) and requested further explanations about corporate governance.

A recent study by Belcredi and Enriques (2015) reported a “non-negligible” volume of activism from institutional investors at firm level. This included pressure on senior management, usually on corporate governance and/or strategic issues, possibly accompanied by “voice” at shareholders’ meetings as well as the presentation of slates and the consequent appointment of “minority” directors on the boards of Italian listed firms. Active institutional investors may alternatively seek to collude with the controlling shareholder to share in private benefits extraction or take an adversarial stance, aimed at monitoring the controlling shareholder, especially where the latter does not hold a majority stake. The case illustrated in Box 5.3 provides an excellent, yet rare, case in point of shareholder activism.

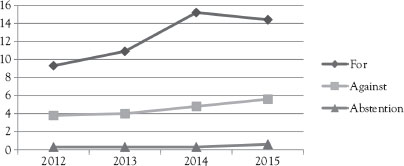

Belcredi and Enriques (2015) report anecdotal evidence, which shows that institutional investors often adopt different strategies depending on the circumstances. For example, they are more active in dissenting on the executive compensation. Shareholder dissent on the compensation policy is generally small in Italy, yet increasing the most recent years. Overall, it is still comparable with that found in the United Kingdom and the United States, where ownership is much more dispersed and, consequently, chances that dissent will successfully drive change are much higher (see Figure 5.5).

Box 5.3 The Case of Shareholder Activism against the Reorganization of Olivetti in 1999

In 1999, Mr. Colaninno, CEO and the controlling shareholder of Olivetti, announced a plan for the transfer of a 60 percent control stake in TIM from Telecom Italia to Tecnost, a debt-laden subsidiary of Olivetti.

The plan was viewed as an attempt to increase the cash flows available to repair Tecnost’s debt as the group would no longer have to distribute part of the dividends paid by the highly profitable TIM to Telecom Italia’s minority shareholders.

In exchange, Telecom Italia’s minority shareholders would have been “compensated” for the loss of their indirect TIM stake with Tecnost’s new shares. Since issuing new Tecnost shares would dilute Olivetti’s existing stake and Colaninno did not want to weaken his control over the whole group, a key issue was the number of new Tecnost shares paid in compensation for each Telecom Italia share held by the minority shareholders. Olivetti offered to pay between 1.5 and 1.65 Tecnost shares for each Telecom Italia share.

Several institutional investors, including the Canadian activist TIAA-CREF, publicly protested and threatened lawsuits. The Economist defined the plan as “downright insulting.”

Following the criticism, Olivetti commissioned an independent analysis. As analysts recommended an exchange rate equals to 2.2–2.5 Tecnost shares for each Telecom Italia share, Olivetti decided to cancel the plan.

Sources: The Economist (1999); Kruse (2007); Mengoli, Pazzaglia, and Sapienza (2009).

Dissent has been found to be significantly higher when the level of disclosure, especially on the variable components of CEO pay, is low and where CEO overall compensation is high, while it is only weakly related with firm performance. In particular, minority shareholders favor the disclosure of much detailed information and are more likely to vote against if the compensation report does not provide such information, especially for what concerns variable compensation. However, while low disclosure is likely to attract some negative votes, cases of high dissent are mostly related to the amount paid to executives. Overall, high level of dissent is rare. Only in 7.5 percent of Italian nonfinancial listed firms dissent was higher than 20 percent of votes cast. This frequency is lower than in the United States (14.6 percent) and in the United Kingdom (26.5 percent), but is similar to that one reported for Germany, where dissent exceeded 25 percent of the votes cast in only 6.7 percent of the firms (Belcredi et al. 2014).

Figure 5.5 Shareholders’ say-on-pay at the AGMs of Italian listed companies in the FTSE-MIB and Mid Cap indexes

Source: CoNSoB (2016).

Note: Percentage of ordinary shares on ordinary total capital (including the capital not represented at the AGM).

From a comparative perspective, the most peculiar form of shareholders’ activism involves submitting and voting “minority slates” (i.e., slates from minority shareholders) at corporate elections. A recent study that analyzed board elections in Italy found that institutional investors are more likely to be active in large and/or politically relevant firms (e.g., State-controlled firms) and when they have a large interest at stake (Belcredi, Bozzi, Di Noia 2013). This evidence is in line with the role of Assogestioni, whose committee has so far played a coordination role in selecting board candidates and submitting slates. Candidates are drawn from a list of names prepared by a primary executive search consultant. Nominating high-profile directors, such as former business leaders and academics, in highly visible and often politically sensitive firms is a way to exercise power at the institutional level (Belcredi and Enriques 2015).

Belcredi and Enriques (2015) report that the level and type of activism varies depending on the characteristics of the institutional investor. U.S.-style active pension funds are substantially absent in the Italian context. The only remarkable case of a pension fund actively targeting Italian companies has been Hermes Focus. Although Hermes Focus tends to prefer private negotiations (Becht et al. 2009), it publicly took a confrontational position in some cases, including the well-known Parmalat scandal, where Hermes Focus complained about insufficient disclosure and related-parties transactions (Melis 2005).

Mutual funds have increasingly become a significant minority shareholder in many Italian listed firms. Consistently with other countries’ experience (Armour and Cheffins 2012), mutual fund activism has usually been “low-cost” (e.g., shareholder proposals and voting)5 and focused on corporate governance issues, such as lack of disclosure and related-parties transactions that could imply minority shareholders’ expropriation. This is not surprising as mutual funds tend to hold small stakes, their investment horizon is usually short-term and activism may negatively affect their portfolio liquidity.6

However, since a relatively small number of listed firms account for a large stake of market capitalization in Italy, mutual funds wishing to invest in Italy have no real alternative to buying those shares. Hence, a substantial part of their investment is, in fact, long-term (Belcredi, Bozzi, Di Noia 2013). In addition, Italian mutual funds are often managed by subsidiaries of banks and insurance firms. This could affect their incentives for being active against the controlling shareholders as they can be current or potential future clients (Bellini 2009). For this reason the association of Italian asset managers, Assogestioni, has adopted a number of provisions (including the separation between the selection of candidates, advanced by a committee based at the association, and submitting and voting of individual slates, performed by individual asset managers) to tackle this potential conflict of interest. However, Belcredi and Enriques (2015) report anecdotal evidence, which seems to support the view that Italian mutual funds are less prone to be active in financial listed firms.

Activist hedge funds operating in Italy have been rather cautious or, at least, discreet. They either failed to exercise their voting rights or, in some cases, supported with their votes the controlling shareholder(s) (Erede 2013). However, in some remarkable exceptions, they targeted listed firms engaging in controversial transactions (Bellini 2009; Belcredi and Enriques 2015). For example, in 2011 Amber Capital sent a petition to the board of statutory auditors of Fondiaria-Sai, an important insurance listed firm, inviting the statutory auditors to investigate on a number of related-parties transactions with family members of the controlling block-holder. In response, the board of statutory auditors issued a report, which was included in the documents for the 2012 shareholders’ general meeting. When the senior top management of the firm underwent criminal investigations for securities fraud in 2013, public prosecutors extensively drew from this report (Belcredi and Enriques 2015).

Hedge funds have also sometimes voiced their discontent openly at the shareholders’ general meeting. However, these interventions are unlikely to be successful given the prevailing concentrated ownership and control structure of Italian listed firms. With a strategy that is rather common around the world (Mallin 2012), open dissent is most likely to be the last stage of unsuccessful engagement with senior management through quiet negotiations (Belcredi and Enriques 2015). For example, the Financial Times (2009) reported a case of a U.S. activist investor, Knight Vinke Asset Management, which has been calling for ENI, the State-controlled Italian oil and gas group, to break itself up as it argued that ENI was overgeared for an exploration and production firm, while Snam Rete Gas, a regulated utility controlled by ENI, was undergeared. Erede (2013) reports three attempts by hedge funds to change a firm’s dividend policy; however, only Amber Capital successfully challenged the dividend policy of Iride, a public utilities firm jointly controlled by the municipalities of Turin and Genoa in Northern Italy. A more systematic study on a sample of 276 Italian nonfinancial listed firms found that firms with a higher risk of expropriation of minority shareholders are more likely to use larger dividend ratios in total payout than counterparts where this risk is lower. These firms distribute dividends to shareholders to mitigate agency conflicts between controlling and minority shareholders (De Cesari 2012).

Despite the evolution of corporate law and corporate governance led to an increase in the protection of minority shareholders’ rights, the ownership structure of Italian nonfinancial listed firms is still highly concentrated, in line with that of other major continental European firms. The controlling shareholder is usually represented by wealthy entrepreneurial families, while the State and some public administrations still held a controlling stake on few large companies.

CEMs (governance devices widely used in continental Europe) allow controlling shareholders to increase their power over the company in excess of their investment. The CEMs that are more widely used by Italian listed firms are: pyramidal groups, (nonvoting) preference shares, shareholders agreements, voting right ceilings, and priority golden share.

During the last two decades, Italy’s corporate law has increased minority shareholders’ powers in order to protect their interests and counterbalance the power of the controlling shareholders. As a consequence, institutional investors have become active and started to both lobbying Italian policymakers to improve corporate governance and influencing firm-level corporate decisions to avoid expropriation by the controlling shareholder. The most typical form of shareholders’ activism in Italy involves submitting and voting “minority slates” (i.e., slates from minority shareholders).

1 In the academic literature this agency problem is often named “principal– principal” agency problem, or agency II type of problem, to differentiate it from the “principal-agent” agency problem, that is, the agency I type of problem that arises between senior managers and shareholders.

2 If the large blockholder is an institution (e.g., a bank, an investment fund, or a widely held firm), the private benefits of control are diluted among several independent owners. Therefore, the large blockholder’s incentives for expropriating minority shareholders are small, but so are its incentives for monitoring executives, so we revert to the “classical” agency problem for those firms. See, for example, Amit and Villalonga (2006).

3 An article of the Financial Times (1998: 16) effectively summarized the “feeling” of the international investors as follows “The best thing for Italy would be if Mr Tanzi’s efforts failed.”

4 The case of the well-known U.S. firm Google provides an exemplary case of this argument. Google decided to issue multiple voting rights shares. Its founders and CEO owned approximately 90 percent of the outstanding class B shares, which gave them over 65 percent of the firm’s total voting rights, while their economic interest was only approx. 20 percent. The use of this CEM did not seem to detract investors from buying their class A shares. The fact that Google ranked high on the Financial Times Global 500 largest companies in 2014 seems to indicate that CEMs do not necessarily have a detrimental effect on firm value, although institutional investors expressed concerns about Google’s choice.

5 These shareholder activism devices share an appealing feature: their cost is modest and they do not require a significant equity stake in the firm. See Ferri (2012).

6 Any contact with appointed directors exposes any investor to the risk of violations (or limitations to trading) under the market abuse legislation. This risk is higher for asset managers as they actively trade in the stock. See Belcredi, Bozzi, and Di Noia (2013).