Regulations of the Oil Industry

Regulation of the petroleum industry is complicated. Within the United States, numerous environmental agencies have regulations that affect exploration, development, and production both onshore and offshore. However, in international locations, each country has developed its own guidelines, which often are not as stable as the industry would like. There are unique locations such as Antarctica that have special international treaties. Oil and gas industry companies have to learn about various regulations that affect the work they do, from initial exploration through development and production, and reporting of the reserves. Many oil and gas companies hire outside environmental experts to ensure compliance with both current and proposed regulations. These regulations may be in the form of protocols, treaties, or contract agreements.

5.1 United States Regulations

5.2 Operating Outside the United States

5.3 Agreements

5.4 Special Regulatory Areas

5.5 Reserves Reporting

5.1 United States Regulations

The United States has a well-developed regulatory environment at both federal and state levels. The states regulate the assignment of drilling permits within their borders and define the allowed distance between wells. For example, in the state of West Virginia, the Office of Oil and Gas is responsible for monitoring and regulating all actions related to the exploration, drilling, storage, and production of oil and natural gas in the state. It maintains records on over 55,000 active and 12,000 inactive oil and gas wells. It manages the Abandoned Well Plugging and Reclamation Program. It ensures that surface/groundwater is protected from oil and gas activities.1

The Bureau of Land Management (BLM)2 within the Department of the Interior (DOI)3 regulates drilling permits/leases on federal or Native American lands. The BLM has authority over oil/gas development and production on these lands, and along with state governments, it offers the leases at auctions.

The DOI also manages offshore federal leases. It is responsible for overseeing the safe and environmentally responsible development of energy and mineral resources on the Outer Continental Shelf.

At the federal level, the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA)4 regulates many aspects of the oil and gasoline industry. The EPA regulates drilling and production operations such as the development of secure storage and the control of emissions from storage tanks, refineries, and natural gas plants.

Safety regulations have become a vital part of oil companies’ core values. Dangerous working conditions can cost lives, money, and do irreparable damage to a company’s image. Offshore drilling platforms are under extreme scrutiny due to the increased operational/environmental risks associated with them. Refineries likewise face strict regulations related to nitrous oxide and other emissions. There are safety standards built into product manufacturing and selling of those products. States may regulate the type of gasoline a refinery may produce and when they can produce it.

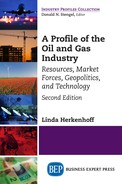

The U.S. Department of Transportation Pipeline and Hazardous Materials Safety Administration (PHMSA)5 is the regulatory body that inspects pipelines to ensure that they comply with safety regulations. Since pipelines are the safest way to move oil, interstate pipelines have federally mandated inspections every five years, and many are inspected more often than that.

Some of the key inspection metrics are associated with pipeline pressure, corrosion, leaks, water crossings (Exhibit 5.1), wildlife, and other environmental factors. It is typical for companies that operate pipelines to hire employees to perform safety and reliability tests to ensure that their pipelines are in compliance with the associated regulations.

Exhibit 5.1 Pipeline water crossing

Source: Steve Hillebrand, www.images.fws.gov.

State and federal regulations (enforced by the EPA) also apply to gas station owners. Florida recently implemented new regulations requiring many station owners to replace existing underground storage tanks with double-walled tanks that can hold gasoline containing up to 10% ethanol.

Gas station owners who cannot afford to update their storage tanks may be forced to close. California implemented a similar law in the 1990s.

Congress created the Commodity Futures Trading Commission (CFTC)6 in 1974 as an independent agency. The CFTC regulates commodity futures and options markets in the United States and has the authority to develop and enforce the regulatory framework that governs the trading of all commodity futures, including crude oil.

When oil trading started on the New York Mercantile Exchange (NYMEX), the U.S. federal authorities phased out price contracts and other regulations. The Dodd-Frank Wall Street Reform and Consumer Protection Act7 (“Dodd Frank”) authorizes the CFTC to comprehensively regulate energy-trading activities. Dodd Frank, which came into effect in early 2013, is intended to increase transparency and reduce the risk of default. The way oil and gas companies manage their trading operations and business risk has been impacted greatly by Dodd Frank.

The Federal Trade Commission (FTC)8 is the lead enforcing body of antitrust laws in the petroleum industry. The Commission’s mission is to ensure the welfare of consumers, while preserving competition in the oil industry. The Commission monitors wholesale and retail gasoline prices, and reviews any instances of illegal mergers or anticompetitive conduct.

The U.S. Energy Independence and Security Act of 2007 (EISA) set a goal for ethanol and biodiesel production that requires fuel producers to produce at least 36 billion gallons of biofuel by 2022. Section 142 requires federal agencies “to achieve at least a 20% reduction in annual petroleum consumption and a 10% increase in annual alternative fuel consumption by 2015 from a 2005 baseline.”9 Fuel producers must report annually on Fuel producers must report annually on their progress.

The Interstate Commerce Commission (ICC) regulated rates and access to oil/gas until 1977, at which point the Federal Energy Resource Commission (FERC)10 became the regulatory body. These particular regulations are in place to assure equal access for shippers at cost-based rates. For example, a refiner may not be able to process at full capacity because of limited access to a pipeline. FERC regulates interstate crude oil and product pipelines as common carriers, which provide open access to any would-be shipper.

In the United States, the Maritime Transportation Security Act of 2002 (MTSA)11 covers certain petroleum facilities that operate within a maritime framework, relative to their security plans. The U.S. Coast Guard supports these regulations that require certain vessels and port facilities that could be involved in a transportation security incident to prepare a vessel or facility plan or both.

The U.S. Clean Air Act (CAA)12 of 1963 was designed to help reduce air pollution at a national level. The Clean Air Act Amendments of 1990 are concerned with toxic combustion by-products. A typical source of air toxins at oil refineries is emissions from petrochemical process heaters.

The U.S. EPA founded in 1970 is responsible for creating and enforcing the National Ambient Air Quality Standards (NAAQS)13 that regulate the minimum-acceptable pollutant levels in the atmosphere. The state of California is the only state allowed to set its own air quality standards and emission controls as these standards are more restrictive than those of the EPA. The California Air Resources Board (CARB)14 is the regulatory agency for those standards. In the 1960s, California introduced gasoline and distillate fuel content regulations. It was not until the 1970s that other states implemented similar regulations. CARB sets vehicle emission standards as well.

In terms of ownership regulation, the United States is one of the few countries along with Canada in which private industry and organizations can own mineral rights (oil/gas/minerals) on privately held land. The U.S. government only owns the rights to minerals on U.S. federal lands. Approximately one-third of mineral rights in the United States is owned by the government. In most other countries, the government owns 100% of the mineral rights both on and offshore. Offshore, the U.S. states own mineral rights out to three nautical miles from the shore, except Florida and Texas, which have a nine nautical mile regulation. The U.S. federal government owns sea-bottom mineral rights beyond state waters out to 200 nautical miles.

The access to private mineral rights in the United States has meant that early development risks in fracking for shale oil/gas were assumed by the small-time entrepreneurs who were rapidly drilling many dry holes on their private land. Without this aspect of private mineral rights, Europe has faced delayed exploration and production of shale fields waiting for government approval. Larger commercial producers in the United States are now attracted to these fields after viewing the important geologic information gathered by smaller private developers. Shale oil and gas will be discussed in more detail in Chapter 6.

The Obama administration tightened regulations on the oil and gas industry in April 2012, requiring drillers to capture emissions of certain air pollutants from new wells. Because the industry had concerns that the rules were being enacted too quickly, the EPA said that companies can burn the pollutants at the wellhead until the start of 2015, when enough equipment is expected to be available to capture the pollution.

The administration said that the regulations are part of President Obama’s promise to develop the nation’s oil and gas resources in a manner that protects the environment and public health.

But what about removing regulations once they are in place? A classic example here in the United States was the deregulation of the oil industry. Phased decontrol of oil prices in the United States began in 1979 under the Carter administration in fulfillment of the terms of the Energy Policy and Conservation Act of 1975.15 Eight months before full decontrol would have taken place, President Reagan ended the program, and prices were fully decontrolled. Deregulation, as in this case, was motivated by the desire for an increase in domestic oil production, which in fact did not materialize. However, the decontrol allowed for increased imports of gasoline and other fuels, which in turn caused a decrease in gasoline prices domestically. Without a doubt, the addition or removal of regulations has a cascading effect throughout this industry.

5.2 Operating Outside the United States

No matter where we are in the world, conflict can occur between regulatory bodies. This section begins with a recent overseas example of the Frade oil spill in late 2011 offshore Brazil, in which less than 3,000 barrels of oil escaped from the sea floor and never reached the shore. In August 2012, a panel of three Brazilian Federal judges voted 3 to 0 to reject arguments from Agência Nacional do Petróleo, Gás Natural e Biocombustíveis (ANP), the Brazilian oil regulatory agency that has statutory rights to decide who operates in the Brazilian oil sector. Typically, ANP’s power has prevailed over the courts. In this case, the judges believed that ANP’s lack of due diligence contributed to the oil spill. The resulting judgment came from the judges, not ANP, resulting in the ban of two international companies, Chevron and Transocean, from operating in Brazil. The ban was lifted after about one year.

International regulations and standards are developed to reduce the costs associated with the procurement of oil and gas industry materials, equipment, and structures, and to enhance efficiency in the use of resources that would otherwise be required to develop and maintain local standards. Regulations are also important in the area of standardization of oil and gas finished products. Standardization facilitates a stable and reliable supply of petroleum products. Standardization allows for travel over longer distances as drivers know that a fuel of the same quality will be available along the route. It allows regulators to set common rules and environmental controls for each type of fuel.

The regulations and standards developed by international groups fall within three broad groups:

- Protect health and property from the by-products of burning oil.

- Ensure safe and secure storage/transport to prevent toxic spills and explosions.

- Establish greenhouse gas (GHG) regulations to reduce environmentally dangerous gases in the atmosphere with a special focus on carbon dioxide.

These regulations are created by recognized international Standards Development Organizations (SDOs) such as the American Society of Testing and Materials (ASTM)16 and the International Standards Organization (ISO).17 Some of the standards developed by regional or national SDOs, or by industry organizations, are also used internationally. Examples are standards developed by the British Standards Institution (BSI)18 and the American Petroleum Institute (API).19 Global standards are national or regional standards with widespread international use. International standards give state-of-the-art specifications for products, services, and best practices, attempting to make the industry more efficient and effective. They often reduce international trade barriers as they are developed through global consensus.

ISO founded in 1947, is the world’s largest developer of voluntary international standards. ISO is an independent, nongovernmental organization made up of members from the national standards bodies of 164 countries, with a Central Secretariat in Geneva, Switzerland, that coordinates the system. This organization has published more than 19,500 international standards, which include many specifically pertaining to the oil and gas industry.

ASTM International was organized in 1898, and is one of the largest voluntary standards-developing organizations in the world. ASTM’s members include producers, users, consumers, governments, and academia from over 100 countries. ASTM develops technical documents that are a basis for manufacturing, management, procurement, codes, and regulations.

The Organization of International Oil and Gas Producers (OIGP)20 compiles input received from members of the OIGP Standards Committee, who are asked to identify international standards used in their organizations. This information is then summarized in a standards report. Recent well accidents motivated the OIGP in July 2010 to establish the Global Industry Response Group (GIRG)21 to identify, learn from, and apply the lessons of Macondo (Gulf of Mexico 2010), Montara (Timor Sea 2009), and similar well accidents. The GIRG’s Oil Spill Response Subgroup was formed in August 2010 to deal with the global aspects of the response to the Macondo incident in the Gulf of Mexico (Exhibit 5.2). The Macondo blowout killed 11 workers and released 3.2 billion barrels of oil into the Gulf of Mexico over a period of three months. The estimated final cost to BP is approximately $61.6 billion.

Exhibit 5.2 Deepwater Horizon Platform in Macondo Field, Gulf of Mexico

From: U.S. Coast Guard, Wikimedia Commons.

In 2011, GIRG published their recommendations for improving well incident prevention, intervention, and response capability. Their key recommendation was to form three new entities to manage and implement the delivery of those GIRG recommendations.

The first is OIGP’s Wells Expert Committee (WEC), which is working to analyze well incident report data, advocate harmonized standards, communicate good practice, and promote continued research and development.

The second is a consortium of nine major oil companies, known as the Sub-sea Well Response Project (SWRP). SWRP is working to design a capping toolbox with a range of equipment to allow wells to be shut in, to design additional hardware for the subsea injection of dispersant, and to further assess the need for and feasibility of global containment solutions. The final body is a joint industry group to manage the recommendations on oil spill response. This body is developing new recommended practices, improving understanding of oil spill response tools and methodologies, and enhancing coordination between key stakeholders internationally.

Individual countries such as the United States and Canada have added other pollution control regulations as well. U.S. regulations and standards tend to be followed in the Americas, excluding Brazil, whereas the European regulations are followed by the Asian countries, Australia, and Brazil. Japan has its own regulations, and Singapore follows the regulations from all of the regions.

5.3 Agreements

There are many forms of agreements that can include protocols, conventions, treaties, and various forms of contractual documents. A protocol is a formal agreement between nation states. The Kyoto Protocol is one of the most important for the oil and gas industry, but it is also one of the most controversial. A convention is a legally binding agreement concluded under international law. The Oslo and Paris Convention (OSPAR)22 is the current regulatory instrument of international cooperation on environmental protection in the North-East Atlantic. The major distinction between a protocol and a convention is that whereas the convention encourages nation countries to follow the terms of the agreement, a protocol commits them to do so. The protocol places a heavier burden on signing nations under the principle of “common but differentiated responsibilities.” International treaties can, over time, obtain the status of customary international law.

Kyoto Protocol

The Kyoto Protocol23 is an international agreement linked to the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCC)24 adopted in Kyoto, Japan, in December 1997. The associated guidelines and standards came into effect in February 2005. The major feature of the Kyoto Protocol is that it sets binding targets for 37 industrialized countries and for the European community, for the reduction of GHG emissions. These countries have collectively agreed to reduce their greenhouse gas emissions by 5.2% on an average for the period 2008 to 2012. This reduction is relative to their annual emissions in a base year, usually chosen as 1990.

As of September 2012, 190 states have signed and ratified the protocol as well as one supranational union (European Union); this includes 188 United Nations (UN) member states as well as Cook Islands and Nive. The only remaining signatory not to have ratified the protocol is the United States. Other UN member states that did not ratify the protocol are Afghanistan, Andorra, and South Sudan. In December 2011, Canada renounced the protocol. Canada has become the first original Kyoto Protocol signatory to withdraw from the agreement. The reason cited is that this will save Canada an estimated $14 billion in penalties25 as it would not be able to meet the environmental thresholds due by the target dates. Countries are working toward a legal obligation by 2020, but the agreement is to be finalized by 2015.

Marine Conventions

At present, over 70 international conventions and agreements are directly concerned with protecting the marine environment. Many of them focus on dealing with marine oil pollution incidents nationally and in cooperation with other countries. However, none of them is specifically devoted to regulating offshore oil and gas development. In practice, these problems are usually solved either at the national level or within the framework of the existing international conventions.

Contractual Agreements

Nationally owned oil companies (NOCs) have their own regulations that vary by country. Regulations and contractual obligations between host countries and international oil companies (IOCs) can fall into several different categories such as concession agreement, product-sharing agreement (PSA), joint-operating agreement (JOA), and service/production contract agreement (SCA and PCA).

Concession Agreement

In the concession agreement, the IOC is granted an exclusion concession. An agreement in which a government, especially a local government, gives preferential treatment to a private-sector company is considered as a concession agreement. Usually a concession agreement involves special tax considerations and is designed to encourage a company to begin operations and then remain in the area. The idea is to provide incentives that encourage a longer-term relationship between the two parties. Governments may make concession agreements to help promote job growth and stability. The entire cost and risk of exploration/development is absorbed by the company. The company typically is expected to pay bonuses, taxes, and/or royalties on production to the host government. If the production is lower than expected, there is always the risk that the government may change the terms of the concession, even with a signed agreement.

Production-Sharing Agreement (PSA)

PSAs have been around for some time, with some of the first being recorded in Bolivia in the early 1950s. PSAs allow the company to complete exploration and production of potential fields in the host country. The oil company takes on all risk associated with the operations. Profit from any produced oil can be used against the initial capital and operational expenditures; this is known as “cost oil.” The remaining money is known as “profit oil” and is split between the government and the company. The going rate varies, but typically it is about 80% for the government and 20% for the company. Volatility in oil prices or production rate can affect the company’s share of production, PSA can be beneficial to countries that lack the expertise or capital or both to develop their resources.

Joint-Operating Agreement (JOA)

JOAs are contracts between cotenants or separate owners of oil and gas properties that are being jointly operated. One of the parties is designated as the operator and takes on the associated roles and responsibilities. However, all parties share in the expenses of the operations and in any profits resulting from the development of the field. The operator receives a small fee, typically only a small percentage of expenditures, for the extra responsibility of operating the field.

Service/Production Contract Agreement (SCA/PCA)

In the SCA, the operating company is paid a fee for specific services. In the PCA, the operating company is paid a portion of increased production. Leases are set up by governments typically through competitive auction. Governments usually define a finite window of time in which a certain number of wells must be drilled. Upfront bonuses may be provided after discovery, and royalty fees typically range from 13 to 15% as part of the lease arrangement.

5.4 Special Regulatory Areas

Certain geographic areas around the world require the coordination and collaboration of several international governments. Three of the most important areas are included in this section: the North-East Atlantic, the Arctic, and the Antarctic.

The North-East Atlantic

The OSPAR is the current regulatory instrument of international cooperation on environmental protection in the North-East Atlantic. It combines and updates the 1972 Oslo Convention on dumping waste in the sea and the 1974 Paris Convention on land-based sources of marine pollution. Work carried out under the convention is managed by the OSPAR Commission, which is made up of representatives of the governments of the 15 signatory nations and representatives of the European Commission. At the regional level, OIGP is the industry representative to the European Commission and Parliament and the OSPAR Commission. Equally important is OIGP’s role in promoting best practices in the areas of health, safety, the environment, and social responsibility for the North-East Atlantic.

The Continental Shelf Convention was agreed upon in 1958 but not ratified by enough of the North Sea countries until 1964.26 The convention laid out the actual boundaries for division of the mineral rights among the countries that border the North Sea: Norway, United Kingdom, Germany, Denmark, Belgium, France, and the Netherlands.

The Arctic

The Arctic standards ensure the use of best practices that address the risks associated with this specific area of exploration. Regulations are in place to protect the environment. One example is the ISO standard for the safe and reliable design of offshore structures on ice. The Arctic Council (AC)27 has recently revised their Arctic offshore oil- and gas-operating guidelines for the pan-Arctic area. They have also developed regulatory controls for Arctic operations, including, but not limited to, offshore structures.

Under international law, no country currently owns the North Pole or the region of the Arctic Ocean surrounding it. The five surrounding Arctic countries, Russia, the United States (via Alaska), Canada, Norway, and Denmark (via Greenland), are limited to an exclusive economic zone (EEZ) of 200 nautical miles (370 km; 230 mi) adjacent to their coasts.

Upon ratification of the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS),28 a country has a 10-year period to make claims to an extended continental shelf that, if validated, gives it exclusive rights to resources on or below the seabed of that extended shelf area. Norway ratified the convention in 1996, Russia ratified in 1997, Canada ratified in 2003, and Denmark ratified in 2004.The United States has signed, but not yet ratified the UNCLOS.

The handling of the Arctic region remains highly controversial. Canada, Denmark, Norway, Russia, and the United States consider territorial waters out to 12 nautical miles from their respective coastlines to be categorized as their own “national waters.” Not everyone agrees with that for a variety of security and financial reasons. The Russians are laying claim to the underwater Lomonosov Ridge. This ridge covers about half of the Arctic area. Water passages that are deemed to be “international seaways” such as the Northwest Passage and the Northern Sea Route are also under discussion. This includes defining international guidelines for operating in these waters. Foreign ministers and other officials representing Canada, Denmark, Norway, Russia, and the United States met in Ilulissat, Greenland in May 2008, at the Arctic Ocean Conference and announced the Ilulissat Declaration.29 The declaration states that any demarcation issues in the Arctic should be resolved on a bilateral basis between contesting parties.

Fishing rights are an important issue, including defining the responsibilities in managing the Arctic fish stocks.

With the advent of global warming and the accompanying melting of Arctic ice, access to minerals and oil/gas fields is opening up. The responsibilities of oil spill cleanups and other environmental pollution needs to still be clearly addressed, especially under the extreme conditions of the Arctic. Exhibit 5.3 shows typical ice conditions facing vessels working in the Arctic seas.

Exhibit 5.3 Arctic sea ice

Source: www.climate.gov.

Antarctica

The Convention on the Regulation of Antarctic Mineral Resource Activities (CRAMRA)30 was completed in 1988 after six years of negotiation. The Convention was developed to address the legal issues involved with any future Antarctica oil and mineral development. It is widely recognized that CRAMRA is one of the longest and most complicated of all of the Antarctic treaties, but it deals with a very complex and controversial topic. The treaty establishes a legal framework for future exploration and development of minerals and oil/gas in Antarctica. To date, it has been impossible to get any of the governments with claims to territorial sovereignty to ratify the treaty. If ratified, the Convention will become part of the Antarctic Treaty system alongside the Antarctic Treaty.

CRAMRA was effectively replaced by the 1991 Protocol on Environmental Protection to the Antarctic Treaty (Madrid Protocol). Currently, all mineral resource activities, except scientific research, are prohibited under Article 7 of the Protocol on Environmental Protection31 to the Antarctic Treaty.

Under the Convention, no Antarctic mineral resource activity can take place until it has been deemed safe for Antarctica’s environment, and has no impact on global weather patterns.

For the last eight years, countries have abided by an informal development moratorium because the Antarctic Treaty does not specifically address the issue of mineral exploration and development. The Convention opens up most of Antarctica, except certain protected areas, to regulated oil and mineral resources development. But the economics are challenging, and interest by the oil and mining companies has been minimal. Until the Convention is ratified and an oversight commission is established, mining and oil/gas exploration will remain stalled.

5.5 Reserves Reporting

In general, reserves reporting around the world are not standardized nor are there any external regulations. However, in the United States, the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) sets standards for publicly traded energy corporations for reporting production and reserves. These standards are important as they can prevent overestimated reserves from driving up stock prices. Some argue that regulations in this area are critically needed to help mitigate the political reasons some countries have to deliberately underestimate or overestimate their reserves.

Reserves estimation is not simple and therefore is difficult to standardize, beginning with the definition of what should be included in the estimation figures. Proven reserves are commonly defined only as “discovered resources producible under current technological and economic conditions.” Reserves are not an estimate of the total amount of oil and gas likely to be removed. Some entities include unconventional oil resources in the total. The major oil companies do not publish oil reserve estimates in their annual reports but do report barrels of oil equivalent (BOE), which does include unconventional resources and natural gas.