A class that is declared within another type declaration is called a nested class. Similarly, an interface or an enum type that is declared within another type declaration is called a nested interface or a nested enum type, respectively. A top-level class, enum type, or interface is one that is not nested. By a nested type we mean either a nested class, a nested enum, or a nested interface.

In addition to the top-level types, there are four categories of nested classes, one of nested enum types, and one of nested interfaces, defined by the context these nested types are declared in:

• static member classes, enums, and interfaces

• non-static member classes

• local classes

• anonymous classes

The last three categories are collectively known as inner classes. They differ from non-inner classes in one important aspect: that an instance of an inner class may be associated with an instance of the enclosing class. The instance of the enclosing class is called the immediately enclosing instance. An instance of an inner class can access the members of its immediately enclosing instance by their simple names.

A static member class, enum, or interface can be declared either at the top-level, or in a nested static type. A static class can be instantiated like any ordinary top-level class, using its full name. No enclosing instance is required to instantiate a static member class. An enum or an interface cannot be instantiated with the new operator. Note that there are no non-static member, local, or anonymous interfaces. This is also true for enum types.

Non-static member classes are defined as instance members of other classes, just as fields and instance methods are defined in a class. An instance of a non-static member class always has an enclosing instance associated with it.

Local classes can be defined in the context of a block as in a method body or a local block, just as local variables can be defined in a method body or a local block.

Anonymous classes can be defined as expressions and instantiated on the fly. An instance of a local (or an anonymous) class has an enclosing instance associated with it, if the local (or anonymous) class is declared in a non-static context.

A nested type cannot have the same name as any of its enclosing types.

Locks on nested classes are discussed in Section 13.5, p. 629.

Generic nested classes and interfaces are discussed in Section 14.13, p. 731. It is not possible to declare a generic enum type (Section 14.13, p. 733).

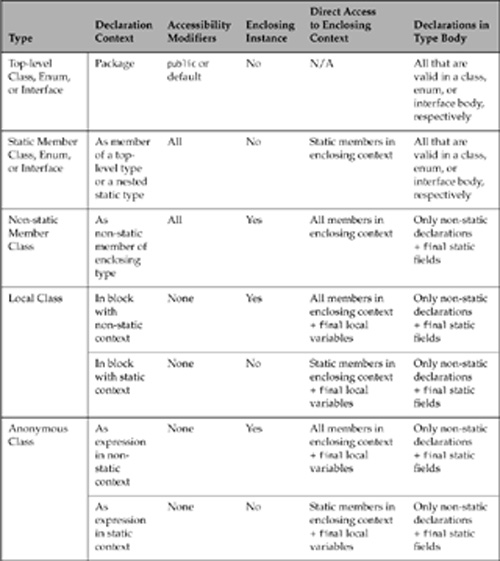

Skeletal code for nested types is shown in Example 8.1. Table 8.1 presents a summary of various aspects relating to nested types. The Type column lists the different kinds of types that can be declared. The Declaration Context column lists the lexical context in which a type can be declared. The Accessibility Modifiers column indicates what accessibility can be specified for the type. The Enclosing Instance column specifies whether an enclosing instance is associated with an instance of the type. The Direct Access to Enclosing Context column lists what is directly accessible in the enclosing context from within the type. The Declarations in Type Body column refers to what can be declared in the body of the type. Subsequent sections on each nested type elaborate on the summary presented in Table 8.1. (N/A in the table means “not applicable”.)

Example 8.1 Overview of Type Declarations

class TLC { // (1) Top level class

static class SMC {/*...*/} // (2) Static member class

interface SMI {/*...*/} // (3) Static member interface

class NSMC {/*...*/} // (4) Non-static member (inner) class

void nsm() {

class NSLC {/*...*/} // (5) Local (inner) class in non-static context

}

static void sm() {

class SLC {/*...*/} // (6) Local (inner) class in static context

}

SMC nsf = new SMC() { // (7) Anonymous (inner) class in non-static context

/*...*/

};

static SMI sf = new SMI() { // (8) Anonymous (inner) class in static context

/*...*/

};

enum SME {/*...*/} // (9) Static member enum

}

Nested types can be regarded as a form of encapsulation, enforcing relationships between types by greater proximity. They allow structuring of types and a special binding relationship between a nested object and its enclosing instance. Used judiciously, they can be beneficial, but unrestrained use of nested types can easily result in unreadable code.

A static member class, enum type, or interface comprises the same declarations as those allowed in an ordinary top-level class, enum type, or interface, respectively. A static member class must be declared explicitly with the keyword static, as a static member of an enclosing type. Nested interfaces are considered implicitly static, the keyword static can, therefore, be omitted. Nested enum types are treated analogously to nested interface in this regard: they are static members.

The accessibility modifiers allowed for members in an enclosing type declaration can naturally be used for nested types. Static member classes, enum types and interfaces can only be declared in top-level type declarations, or within other nested static members.

As regards nesting of types, any further discussion on nested classes and interfaces is also applicable to nested enum types.

In Example 8.2, the top-level class ListPool at (1) contains a static member class MyLinkedList at (2), which in turn defines a static member interface ILink at (3) and a static member class BiNode at (4). The static member class BiNode at (4) implements the static member interface IBiLink at (5). Note that each static member class is defined as static, just like static variables and methods in a top-level class.

Example 8.2 Static Member Types

//Filename: ListPool.java

package smc;

public class ListPool { // (1) Top-level class

public static class MyLinkedList { // (2) Static member class

private interface ILink { } // (3) Static member interface

public static class BiNode

implements IBiLink { } // (4) Static member class

}

interface IBiLink

extends MyLinkedList.ILink { } // (5) Static member interface

}

//Filename: MyBiLinkedList.java

package smc;

public class MyBiLinkedList implements ListPool.IBiLink { // (6)

ListPool.MyLinkedList.BiNode objRef1

= new ListPool.MyLinkedList.BiNode(); // (7)

//ListPool.MyLinkedList.ILink ref; // (8) Compile-time error!

}

The full name of a (static or non-static) member class or interface includes the names of the classes and interfaces it is lexically nested in. For example, the full name of the member class BiNode at (4) is ListPool.MyLinkedList.BiNode. The full name of the member interface IBiLink at (5) is ListPool.IBiLink. Each member class or interface is uniquely identified by this naming syntax, which is a generalization of the naming scheme for packages. The full name can be used in exactly the same way as any other top-level class or interface name, as shown at (6) and (7). Such a member’s fully qualified name is its full name prefixed by the name of its package. For example, the fully qualified name of the member class at (4) is smc.ListPool.MyLinkedList.BiNode. Note that a nested member type cannot have the same name as an enclosing type.

For all intents and purposes, a static member class or interface is very much like any other top-level class or interface. Static variables and methods belong to a class, and not to instances of the class. The same is true for static member classes and interfaces.

Within the scope of its top-level class or interface, a member class or interface can be referenced regardless of its accessibility modifier and lexical nesting, as shown at (5) in Example 8.2. Its accessibility modifier (and that of the types making up its full name) come into play when it is referenced by an external client. The declaration at (8) in Example 8.2 will not compile because the member interface ListPool.MyLinkedList.ILink has private accessibility.

A static member class can be instantiated without any reference to any instance of the enclosing context, as is the case for instantiating top-level classes. An example of creating an instance of a static member class is shown at (7) in Example 8.2 using the new operator.

If the file ListPool.java containing the declarations in Example 8.2 is compiled, it will result in the generation of the following class files in the package smc, where each file corresponds to either a class or an interface declaration:

ListPool$MyLinkedList$BiNode.class

ListPool$MyLinkedList$ILink.class

ListPool$MyLinkedList.class

ListPool$IBiLink.class

ListPool.class

Note how the full class name corresponds to the class file name (minus the extension), with the dollar sign ($) replaced by the dot sign (.).

There is seldom any reason to import nested types from packages. It would undermine the encapsulation achieved by such types. However, a compilation unit can use the import facility to provide a shortcut for the names of member classes and interfaces. Note that type import and static import of nested static types is equivalent: in both cases, a type name is imported. Some variations on usage of the (static) import declaration for static member classes are shown in Example 8.3.

Example 8.3 Importing Static Member Types

//Filename: Client1.java

import smc.ListPool.MyLinkedList; // (1) Type import

public class Client1 {

MyLinkedList.BiNode objRef1 = new MyLinkedList.BiNode();// (2)

}

//Filename: Client2.java

import static smc.ListPool.MyLinkedList.BiNode; // (3) Static import

public class Client2 {

BiNode objRef2 = new BiNode(); // (4)

}

class BiListPool implements smc.ListPool.IBiLink { } // (5) Not accessible!

In the file Client1.java, the import statement at (1) allows the static member class BiNode to be referenced as MyLinkedList.BiNode in (2), whereas in the file Client2.java, the static import at (3) will allow the same class to be referenced using its simple name, as at (4). At (5), the fully qualified name of the static member interface is used in an implements clause. However, the interface smc.ListPool.IBiLink is declared with package accessibility in its enclosing class ListPool in the package smc, and therefore not visible in other packages, including the default package.

Static code does not have a this reference and can, therefore, only directly access other members that are declared static within the same class. Since static member classes are static, they do not have any notion of an enclosing instance. This means that any code in a static member class can only directly access static members, but not instance members, in its enclosing context.

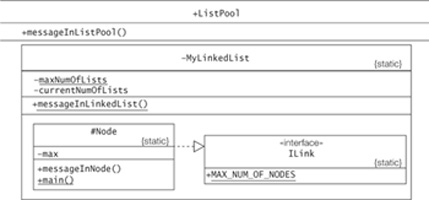

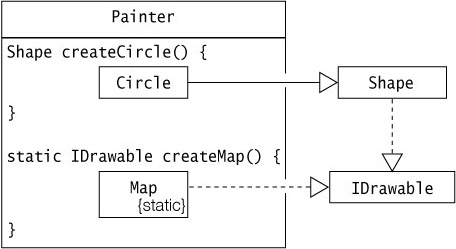

Figure 8.1 is a class diagram that illustrates static member classes and interfaces. These are shown as members of the enclosing context, with the {static} tag to indicate that they are static, i.e., they can be instantiated without regard to any object of the enclosing context. Since they are members of a class or an interface, their accessibility can be specified exactly like that of any other member of a class or interface. The classes from the diagram are implemented in Example 8.4.

Example 8.4 Accessing Members in Enclosing Context (Static Member Classes)

//Filename: ListPool.java

public class ListPool { // Top-level class

public void messageInListPool() { // Instance method

System.out.println("This is a ListPool object.");

}

private static class MyLinkedList { // (1) Static class

private static int maxNumOfLists = 100; // Static variable

private int currentNumOfLists; // Instance variable

public static void messageInLinkedList() { // Static method

System.out.println("This is MyLinkedList class.");

}

interface ILink { int MAX_NUM_OF_NODES = 2000; } // (2) Static interface

protected static class Node implements ILink { // (3) Static class

private int max = MAX_NUM_OF_NODES; // (4) Instance variable

public void messageInNode() { // Instance method

// int currentLists = currentNumOfLists; // (5) Not OK.

int maxLists = maxNumOfLists;

int maxNodes = max;

// messageInListPool(); // (6) Not OK.

messageInLinkedList(); // (7) Call static method

}

public static void main (String[] args) {

int maxLists = maxNumOfLists; // (8)

// int maxNodes = max; // (9) Not OK.

messageInLinkedList(); // (10) Call static method

}

} // Node

} // MyLinkedList

} // ListPool

Compling the program:

>javac ListPool.java

Running the program:

>java ListPool$MyLinkedList$Node

This is MyLinkedList class.

Example 8.4 demonstrates accessing members directly in the enclosing context of class Node defined at (3). The initialization of the field max at (4) is valid, since the field MAX_NUM_OF_NODES, defined in the outer interface ILink at (2), is implicitly static. The compiler will flag an error at (5) and (6) in the method messageInNode() because direct access to non-static members in the enclosing class is not permitted by any method in a static member class. It will also flag an error at (9) in the method main() because a static method cannot access directly other non-static fields in its own class. The statements at (8) and (10) access static members only in the enclosing context. The references in these statements can also be specified using full names.

int maxLists = ListPool.MyLinkedList.maxNumOfLists; // (8')

ListPool.MyLinkedList.messageInLinkedList(); // (10')

Note that a static member class can define both static and instance members, like any other top-level class. However, its code can only directly access static members in its enclosing context.

A static member class, being a member of the enclosing class or interface, can have any accessibility (public, protected, package/default, private), like any other member of a class. The class MyLinkedList at (1) has private accessibility, whereas its nested class Node at (3) has protected accessibility. The class Node defines the method main() which can be executed by the command

>java ListPool$MyLinkedList$Node

Note that the class Node is specified using the full name of the class file minus the extension.

Non-static member classes are inner classes that are defined without the keyword static as members of an enclosing class or interface. Non-static member classes are on par with other non-static members defined in a class. The following aspects about non-static member classes should be noted:

• An instance of a non-static member class can only exist with an instance of its enclosing class. This means that an instance of a non-static member class must be created in the context of an instance of the enclosing class. This also means that a non-static member class cannot have static members. In other words, the non-static member class does not provide any services, only instances of the class do. However, final static variables are allowed, as these are constants.

• Code in a non-static member class can directly refer to any member (including nested) of any enclosing class or interface, including private members. No fully qualified reference is required.

• Since a non-static member class is a member of an enclosing class, it can have any accessibility: public, package/default, protected, or private.

A typical application of non-static member classes is implementing data structures. For example, a class for linked lists could define the nodes in the list with the help of a non-static member class which could be declared private so that it was not accessible outside of the top-level class. Nesting promotes encapsulation, and the close proximity allows classes to exploit each other’s capabilities.

In Example 8.5, the class MyLinkedList at (1) defines a non-static member class Node at (5). The example is in no way a complete implementation for linked lists. Its main purpose is to illustrate nesting and use of non-static member classes.

Example 8.5 Defining and Instantiating Non-static Member Classes

class MyLinkedList { // (1)

private String message = "Shine the light"; // (2)

public Node makeInstance(String info, Node next) // (3)

return new Node(info, next); // (4)

}

public class Node { // (5) NSMC

// static int maxNumOfNodes = 100; // (6) Not OK.

final static int maxNumOfNodes = 100; // (7) OK.

private String nodeInfo; // (8)

private Node next;

public Node(String nodeInfo, Node next) { // (9)

this.nodeInfo = nodeInfo;

this.next = next;

}

public String toString() {

return message + " in " + nodeInfo + " (" + maxNumOfNodes + ")"; // (10)

}

}

}

public class ListClient { // (11)

public static void main(String[] args) { // (12)

MyLinkedList list = new MyLinkedList(); // (13)

MyLinkedList.Node node1 = list.makeInstance("node1", null); // (14)

System.out.println(node1); // (15)

// MyLinkedList.Node nodeX

// = new MyLinkedList.Node("nodeX", node1); // (16) Not OK.

MyLinkedList.Node node2 = list.new Node("node2", node1); // (17)

System.out.println(node2); // (18)

}

}

Output from the program:

Shine the light in node1 (100)

Shine the light in node2 (100)

First, note that in Example 8.5, the declaration of a static variable at (6) in class Node is flagged as a compile-time error, but defining a final static variable at (7) is allowed.

A special form of the new operator is used to instantiate a non-static member class:

<enclosing object reference>.new <non-static member class constructor call>

The <enclosing object reference> in the object creation expression evaluates to an instance of the enclosing class in which the designated non-static member class is defined. A new instance of the non-static member class is created and associated with the indicated instance of the enclosing class. Note that the expression returns a reference value that denotes a new instance of the non-static member class. It is illegal to specify the full name of the non-static member class in the constructor call, as the enclosing context is already given by the <enclosing object reference>.

The non-static method makeInstance() at (3) in the class MyLinkedList creates an instance of the Node using the new operator, as shown at (4):

return new Node(info, next); // (4)

This creates an instance of a non-static member class in the context of the instance of the enclosing class on which the makeInstance() method is invoked. The new operator in the statement at (4) has an implicit this reference as the <enclosing object reference>, since the non-static member class is directly defined in the context of the object denoted by the this reference:

return this.new Node(info, next); // (4')

The makeInstance() method is called at (14). This method call associates an inner object of the Node class with the object denoted by the reference list. This inner object is denoted by the reference node1. This reference can then be used in the normal way to access members of the inner object. An example of such a use is shown at (15) in the print statement where this reference is used to call the toString() method implicitly on the inner object.

An attempt to create an instance of the non-static member class without an outer instance, using the new operator with the full name of the inner class, as shown at (16), results in a compile-time error.

The special form of the new operator is also used in the object creation expression at (17).

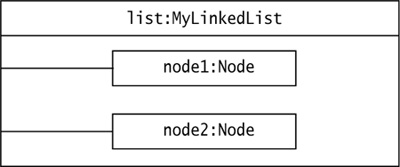

MyLinkedList.Node node2 = list.new Node("node2", node1); // (17)

The reference list denotes an object of the class MyLinkedList. After the execution of the statement at (17), the MyLinkedList object has two instances of the non-static member class Node associated with it. This is depicted in Figure 8.2, where the outer object (denoted by list) of class MyLinkedList is shown with its two associated inner objects (denoted by the references node1 and node2, respectively) right after the execution of the statement at (17). In other words, multiple objects of the non-static member classes can be associated with an object of an enclosing class at runtime.

An implicit reference to the enclosing object is always available in every method and constructor of a non-static member class. A method can explicitly use this reference with a special form of the this construct, as explained in the next example.

From within a non-static member class, it is possible to refer to all members in the enclosing class directly. An example is shown at (10) in Example 8.5, where the field message from the enclosing class is accessed in the non-static member class. It is also possible to explicitly refer to members in the enclosing class, but this requires special usage of the this reference. One might be tempted to write the statement at (10) as follows:

return this.message + " in " + this.nodeInfo +

" (" + this.maxNumOfNodes + ")"; // (10a)

The reference this.nodeInfo is correct, because the field nodeInfo certainly belongs to the current object (denoted by this) of the Node class, but this.message can not possibly work, as the current object (indicated by this) of the Node class has no field named message. The correct syntax is the following:

return MyLinkedList.this.message + " in " + this.nodeInfo +

" (" + this.maxNumOfNodes + ")"; // (10b)

<enclosing class name>.this

evaluates to a reference that denotes the enclosing object (of the class <enclosing class name>) of the current instance of a non-static member class.

Fields and methods in the enclosing context can be hidden by fields and methods with the same names in the non-static member class. The special form of the this syntax can be used to access members in the enclosing context, somewhat analogous to using the keyword super in subclasses to access hidden superclass members.

Example 8.6 Special Form of this and new Constructs in Non-static Member Classes

//Filename: Client2.java

class TLClass { // (1) TLC

private String id = "TLClass "; // (2)

public TLClass(String objId) { id = id + objId; } // (3)

public void printId() { // (4)

System.out.println(id);

}

class InnerB { // (5) NSMC

private String id = "InnerB "; // (6)

public InnerB(String objId) { id = id + objId; } // (7)

public void printId() { // (8)

System.out.print(TLClass.this.id + " : "); // (9) Refers to (2)

System.out.println(id); // (10) Refers to (6)

}

class InnerC { // (11) NSMC

private String id = "InnerC "; // (12)

public InnerC(String objId) { id = id + objId; } // (13)

public void printId() { // (14)

System.out.print(TLClass.this.id + " : "); // (15) Refers to (2)

System.out.print(InnerB.this.id + " : "); // (16) Refers to (6)

System.out.println(id); // (17) Refers to (12)

}

public void printIndividualIds() { // (18)

TLClass.this.printId(); // (19) Calls (4)

InnerB.this.printId(); // (20) Calls (8)

printId(); // (21) Calls (14)

}

} // InnerC

} // InnerB

} // TLClass

//_______________________________________________________

public class OuterInstances { // (22)

public static void main(String[] args) { // (23)

TLClass a = new TLClass("a"); // (24)

TLClass.InnerB b = a.new InnerB("b"); // (25)

TLClass.InnerB.InnerC c1 = b.new InnerC("c1"); // (26)

TLClass.InnerB.InnerC c2 = b.new InnerC("c2"); // (27)

b.printId(); // (28)

c1.printId(); // (29)

c2.printId(); // (30)

TLClass.InnerB bb = new TLClass("aa").new InnerB("bb"); // (31)

TLClass.InnerB.InnerC cc = bb.new InnerC("cc"); // (32)

bb.printId(); // (33)

cc.printId(); // (34)

TLClass.InnerB.InnerC ccc =

new TLClass("aaa").new InnerB("bbb").new InnerC("ccc");// (35)

ccc.printId(); // (36)

System.out.println("------------");

ccc.printIndividualIds(); // (37)

}

}

Output from the program:

TLClass a : InnerB b

TLClass a : InnerB b : InnerC c1

TLClass a : InnerB b : InnerC c2

TLClass aa : InnerB bb

TLClass aa : InnerB bb : InnerC cc

TLClass aaa : InnerB bbb : InnerC ccc

------------

TLClass aaa

TLClass aaa : InnerB bbb

TLClass aaa : InnerB bbb : InnerC ccc

Example 8.6 illustrates the special form of the this construct employed to access members in the enclosing context, and also demonstrates the special form of the new construct employed to create instances of non-static member classes. The example shows the non-static member class InnerC at (11), which is nested in the nonstatic member class InnerB at (5), which in turn is nested in the top-level class TLClass at (1). All three classes have a private non-static String field named id and a non-static method named printId. The member name in the nested class hides the name in the enclosing context. These members are not overridden in the nested classes because no inheritance is involved. In order to refer to the hidden members, the nested class can use the special this construct, as shown at (9), (15), (16), (19), and (20). Within the nested class InnerC, the three forms used in the following statements to access its field id are equivalent:

System.out.println(id); // (17)

System.out.println(this.id); // (17a)

System.out.println(InnerC.this.id); // (17b)

The main() method at (23) uses the special syntax of the new operator to create objects of non-static member classes and associate them with enclosing objects. An instance of class InnerC (denoted by c) is created at (26) in the context of an instance of class InnerB (denoted by b), which was created at (25) in the context of an instance of class TLClass (denoted by a), which in turn was created at (24). The reference c1 is used at (29) to invoke the method printId() declared at (14) in the nested class InnerC. This method prints the field id from all the objects associated with an instance of the nested class InnerC.

When the intervening references to an instance of a non-static member class are of no interest (i.e., if the reference values need not be stored in variables), the new operator can be chained as shown at (31) and (35).

Note that the (outer) objects associated with the instances denoted by the references c1, cc, and ccc are distinct, as evident from the program output. However, the instances denoted by references c1 and c2 have the same outer objects associated with them.

Inner classes can extend other classes, and vice versa. An inherited field (or method) in an inner subclass can hide a field (or method) with the same name in the enclosing context. Using the simple name to access this member will access the inherited member, not the one in the enclosing context.

Example 8.7 illustrates the situation outlined earlier. The standard form of the this reference is used to access the inherited member, as shown at (4). The keyword super would be another alternative. To access the member from the enclosing context, the special form of the this reference together with the enclosing class name is used, as shown at (5).

Example 8.7 Inheritance Hierarchy and Enclosing Context

class Superclass {

protected double x = 3.0e+8;

}

//_______________________________________________________

class TopLevelClass { // (1) Top-level Class

private double x = 3.14;

class Inner extends Superclass { // (2) Non-static member Class

public void printHidden() { // (3)

// (4) x from superclass:

System.out.println("this.x: " + this.x);

// (5) x from enclosing context:

System.out.println("TopLevelClass.this.x: " + TopLevelClass.this.x);

}

} // Inner

} // TopLevelClass

//_______________________________________________________

public class HiddenAndInheritedAccess {

public static void main(String[] args) {

TopLevelClass.Inner ref = new TopLevelClass().new Inner();

ref.printHidden();

}

}

Output from the program:

this.x: 3.0E8

TopLevelClass.this.x: 3.14

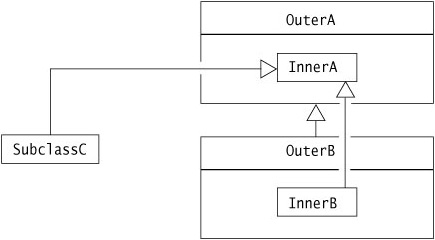

Some caution should be exercised when extending an inner class. Some of the subtleties involved are illustrated by Example 8.8. The nesting and the inheritance hierarchy of the classes involved is shown in Figure 8.3. The question that arises is how do we provide an outer instance when creating a subclass instance of a non-static member class, e.g., when creating objects of the classes SubclassC and OuterB in Figure 8.3.

The non-static member class InnerA, declared at (2) in the class OuterA, is extended by SubclassC at (3). Note that SubclassC and the class OuterA are not related in any way, and that the subclass OuterB inherits the class InnerA from its superclass OuterA. An instance of SubclassC is created at (8). An instance of the class OuterA is explicitly passed as argument in the constructor call to SubclassC. The constructor at (4) for SubclassC has a special super() call in its body at (5). This call ensures that the constructor of the superclass InnerA has an outer object (denoted by the reference outerRef) to bind to. Using the standard super() call in the subclass constructor is not adequate, because it does not provide an outer instance for the superclass constructor to bind to. The non-default constructor at (4) and the outerRef.super() expression at (5) are mandatory to set up the proper relationships between the objects involved.

The outer object problem mentioned above does not arise if the subclass that extends an inner class is also declared within an outer class that extends the outer class of the superclass. This situation is illustrated at (6) and (7): the classes InnerB and OuterB extend the classes InnerA and OuterA, respectively. The type InnerA is inherited by the class OuterB from its superclass OuterA. Thus, an object of class OuterB can act as an outer object for an instance of class InnerA. The object creation expression at (9)

new OuterB().new InnerB();

creates an OuterB object and implicitly passes its reference to the default constructor of class InnerB. The default constructor of class InnerB invokes the default constructor of its superclass InnerA by calling super() and passing it the reference of the OuterB object, which the superclass constructor can readily bind to.

Example 8.8 Extending Inner Classes

class OuterA { // (1)

class InnerA { } // (2)

}

//_______________________________________________________

class SubclassC extends OuterA.InnerA { // (3) Extends NSMC at (2)

// (4) Mandatory non-default constructor:

SubclassC(OuterA outerRef) {

outerRef.super(); // (5) Explicit super() call

}

}

//_______________________________________________________

class OuterB extends OuterA { // (6) Extends class at (1)

class InnerB extends OuterB.InnerA { } // (7) Extends NSMC at (2)

}

//_______________________________________________________

public class Extending {

public static void main(String[] args) {

// (8) Outer instance passed explicitly in constructor call:

new SubclassC(new OuterA());

// (9) No outer instance passed explicitly in constructor call to InnerB:

new OuterB().new InnerB();

}

}

Review Questions

![]()

8.1 What will be the result of compiling and running the following program?

public class MyClass {

public static void main(String[] args) {

Outer objRef = new Outer();

System.out.println(objRef.createInner().getSecret());

}

}

class Outer {

private int secret;

Outer() { secret = 123; }

class Inner {

int getSecret() { return secret; }

}

Inner createInner() { return new Inner(); }

}

Select the one correct answer.

(a) The program will fail to compile because the class Inner cannot be declared within the class Outer.

(b) The program will fail to compile because the method createInner() cannot be allowed to pass objects of the class Inner to methods outside of the class Outer.

(c) The program will fail to compile because the field secret is not accessible from the method getSecret().

(d) The program will fail to compile because the method getSecret() is not visible from the main() method in the class MyClass.

(e) The code will compile and print 123, when run.

8.2 Which statements about nested classes are true?

Select the two correct answers.

(a) An instance of a static member class has an inherent outer instance.

(b) A static member class can contain non-static fields.

(c) A static member interface can contain non-static fields.

(d) A static member interface has an inherent outer instance.

(e) An instance of the outer class can be associated with many instances of a nonstatic member class.

8.3 What will be the result of compiling and running the following program?

public class MyClass {

public static void main(String[] args) {

State st = new State();

System.out.println(st.getValue());

State.Memento mem = st.memento();

st.alterValue();

System.out.println(st.getValue());

mem.restore();

System.out.println(st.getValue());

}

public static class State {

protected int val = 11;

int getValue() { return val; }

void alterValue() { val = (val + 7) % 31; }

Memento memento() { return new Memento(); }

class Memento {

int val;

Memento() { this.val = State.this.val; }

void restore() { ((State) this).val = this.val; }

}

}

}

Select the one correct answer.

(a) The program will fail to compile because the static main() method attempts to create a new instance of the static member class State.

(b) The program will fail to compile because the class State.Memento is not accessible from the main() method.

(c) The program will fail to compile because the non-static member class Memento declares a field with the same name as a field in the outer class State.

(d) The program will fail to compile because the State.this.val expression in the Memento constructor is invalid.

(e) The program will fail to compile because the ((State) this).val expression in the method restore() of the class Memento is invalid.

(f) The program will compile and print 11, 18, and 11, when run.

8.4 What will be the result of compiling and running the following program?

public class Nesting {

public static void main(String[] args) {

B.C obj = new B().new C();

}

}

class A {

int val;

A(int v) { val = v; }

}

class B extends A {

int val = 1;

B() { super(2); }

class C extends A {

int val = 3;

C() {

super(4);

System.out.println(B.this.val);

System.out.println(C.this.val);

System.out.println(super.val);

}

}

}

Select the one correct answer.

(a) The program will fail to compile.

(b) The program will compile and print 2, 3, and 4, in that order, when run.

(c) The program will compile and print 1, 4, and 2, in that order, when run.

(d) The program will compile and print 1, 3, and 4, in that order, when run.

(e) The program will compile and print 3, 2, and 1, in that order, when run.

8.5 Which statements about the following program are true?

public class Outer {

public void doIt() {

}

public class Inner {

public void doIt() {

}

}

public static void main(String[] args) {

new Outer().new Inner().doIt();

}

}

Select the two correct answers.

(a) The doIt() method in the Inner class overrides the doIt() method in the Outer class.

(b) The doIt() method in the Inner class overloads the doIt() method in the Outer class.

(c) The doIt() method in the Inner class hides the doIt() method in the Outer class.

(d) The full name of the Inner class is Outer.Inner.

(e) The program will fail to compile.

8.6 What will be the result of compiling and running the following program?

public class Outer {

private int innerCounter;

class Inner {

Inner() {innerCounter++;}

public String toString() {

return String.valueOf(innerCounter);

}

}

private void multiply() {

Inner inner = new Inner();

this.new Inner();

System.out.print(inner);

inner = new Outer().new Inner();

System.out.println(inner);

}

public static void main(String[] args) {

new Outer().multiply();

}

}

Select the one correct answer.

(a) The program will fail to compile.

(b) The program will compile but throw an exception when run.

(c) The program will compile and print 22, when run.

(d) The program will compile and print 11, when run.

(e) The program will compile and print 12, when run

(f) The program will compile and print 21, when run.

A local class is an inner class that is defined in a block. This could be a method body, a constructor body, a local block, a static initializer, or an instance initializer.

Blocks in a non-static context have a this reference available, which refers to an instance of the class containing the block. An instance of a local class, which is declared in such a non-static block, has an instance of the enclosing class associated with it. This gives such a non-static local class much of the same capability as a non-static member class.

However, if the block containing a local class declaration is defined in a static context (that is, a static method or a static initializer), the local class is implicitly static in the sense that its instantiation does not require any outer object. This aspect of local classes is reminiscent of static member classes. However, note that a local class cannot be specified with the keyword static.

Some restrictions that apply to local classes are

• Local classes cannot have static members, as they cannot provide class-specific services. However, final static fields are allowed, as these are constants. This is illustrated in Example 8.9 at (1) and (2) in the NonStaticLocal class, and also by the StaticLocal class at (11) and (12).

• Local classes cannot have any accessibility modifier. The declaration of the class is only accessible in the context of the block in which it is defined, subject to the same scope rules as for local variable declarations.

Example 8.9 Access in Enclosing Context (Local Classes)

class Base {

protected int nsf1;

}

class TLCWithLocalClasses { // Top level Class

private double nsf1; // Non-static field

private int nsf2; // Non-static field

private static int sf; // Static field

void nonStaticMethod(final int fp) { // Non-static Method

final int flv = 10; // final local variable

final int hlv = 30; // final (hidden) local variable

int nflv = 20; // non-final local variable

class NonStaticLocal extends Base { // Non-static local class

//static int f1; // (1) Not OK. Static members not allowed.

final static int f2 = 10;// (2) final static members allowed.

int f3 = fp; // (3) final param from enclosing method.

int f4 = flv; // (4) final local var from enclosing method.

//double f5 = nflv; // (5) Not OK. Only finals from enclosing method.

double f6 = nsf1; // (6) Inherited from superclass.

double f6a = this.nsf1; // (6a) Inherited from superclass.

double f6b = super.nsf1; // (6b) Inherited from superclass.

double f7 = TLCWithLocalClasses.this.nsf1;// (7) In enclosing object.

int f8 = nsf2; // (8) In enclosing object.

int f9 = sf; // (9) static from enclosing class.

int hlv; // (10) Hides local variable.

}

}

static void staticMethod(final int fp) { // Static Method

final int flv = 10; // final local variable

final int hlv = 30; // final (hidden) local variable

int nflv = 20; // non-final local variable

class StaticLocal extends Base { // Static local class

//static int f1; // (11) Not OK. Static members not allowed.

final static int f2 = 10;// (12) final static members allowed.

int f3 = fp; // (13) final param from enclosing method.

int f4 = flv; // (14) final local var from enclosing method.

//double f5 = nflv; // (15) Not OK. Only finals from enclosing method.

double f6 = nsf1; // (16) Inherited from superclass.

double f6a = this.nsf1; // (16a) Inherited from superclass.

double f6b = super.nsf1; // (16b) Inherited from superclass.

//double f7 = TLCWithLocalClasses.this.nsf1; //(17) No enclosing object.

//int f8 = nsf2; // (18) No enclosing object.

int f9 = sf; // (19) static from enclosing class.

int hlv; // (20) Hides local variable.

}

}

}

Example 8.9 illustrates how a local class can access declarations in its enclosing context. Declaring a local class in a static or a non-static block influences what the class can access in the enclosing context.

A local class can access final local variables, final method parameters, and final catch-block parameters in the scope of the local context. Such final variables are also read-only in the local class. This situation is shown at (3) and (4), where the final parameter fp and the final local variable flv of the method nonStaticMethod() in the NonStaticLocal class are accessed. This also applies to static local classes, as shown at (13) and (14) in the StaticLocal class.

Access to non-final local variables is not permitted from local classes, as shown at (5) and (15).

Declarations in the enclosing block of a local class can be hidden by declarations in the local class. At (10) and (20), the field hlv hides the local variable by the same name in the enclosing method. There is no way for the local class to refer to such hidden declarations.

A local class can access members inherited from its superclass in the usual way. The field nsf1 in the superclass Base is inherited by the local subclass NonStaticLocal. This inherited field is accessed in the NonStaticLocal class, as shown at (6), (6a), and (6b), by using the field’s simple name, the standard this reference, and the super keyword, respectively. This also applies for static local classes, as shown at (16), (16a), and (16b).

Fields and methods in the enclosing class can be hidden by member declarations in the local class. The non-static field nsf1, inherited by the local classes, hides the field by the same name in the class TLCWithLocalClasses. The special form of the this construct can be used in non-static local classes for explicit referencing of members in the enclosing class, regardless of whether these members are hidden or not.

double f7 = TLCWithLocalClasses.this.nsf1; // (7)

However, the special form of the this construct cannot be used in a static local class, as shown at (17), since it does not have any notion of an outer object. The static local class cannot refer to such hidden declarations.

A non-static local class can access both static and non-static members defined in the enclosing class. The non-static field nsf2 and static field sf are defined in the enclosing class TLCWithLocalClasses. They are accessed in the NonStaticLocal class at (8) and (9), respectively. The special form of the this construct can also be used in non-static local classes, as previously mentioned.

However, a static local class can only directly access members defined in the enclosing class that are static. The static field sf in the class TLCWithLocalClasses is accessed in the StaticLocal class at (19), but the non-static field nsf1 cannot be accessed, as shown at (17).

Clients outside the scope of a local class cannot instantiate the class directly because such classes are, after all, local. A local class can be instantiated in the block in which it is defined. Like a local variable, a local class must be declared before being used in the block.

A method can return instances of any local class it declares. The local class type must then be assignable to the return type of the method. The return type cannot be the same as the local class type, since this type is not accessible outside of the method. A supertype of the local class must be specified as the return type. This also means that, in order for the objects of the local class to be useful outside the method, a local class should implement an interface or override the behavior of its supertypes.

Example 8.10 illustrates how clients can instantiate local classes. The nesting and the inheritance hierarchy of the classes involved is shown in Figure 8.4. The nonstatic local class Circle at (5) is defined in the non-static method createCircle() at (4), which has the return type Shape. The static local class Map at (8) is defined in the static method createMap() at (7), which has the return type IDrawable. The main() method creates a polymorphic array drawables of type IDrawable[] at (10), which is initialized at lines (10) through (13) with instances of the local classes.

Example 8.10 Instantiating Local Classes

interface IDrawable { // (1)

void draw();

}

//_______________________________________________________

class Shape implements IDrawable { // (2)

public void draw() { System.out.println("Drawing a Shape."); }

}

//_______________________________________________________

class Painter { // (3) Top-level Class

public Shape createCircle(final double radius) { // (4) Non-static Method

class Circle extends Shape { // (5) Non-static local class

public void draw() {

System.out.println("Drawing a Circle of radius: " + radius);

}

}

return new Circle(); // (6) Object of non-static local class

}

public static IDrawable createMap() { // (7) Static Method

class Map implements IDrawable { // (8) Static local class

public void draw() { System.out.println("Drawing a Map."); }

}

return new Map(); // (9) Object of static local class

}

}

//_______________________________________________________

public class LocalClassClient {

public static void main(String[] args) {

IDrawable[] drawables = { // (10)

new Painter().createCircle(5), // (11) Object of non-static local class

Painter.createMap(), // (12) Object of static local class

new Painter().createMap() // (13) Object of static local class

};

for (int i = 0; i < drawables.length; i++) // (14)

drawables[i].draw();

System.out.println("Local Class Names:");

System.out.println(drawables[0].getClass()); // (15)

System.out.println(drawables[1].getClass()); // (16)

}

}

Output from the program:

Drawing a Circle of radius: 5.0

Drawing a Map.

Drawing a Map.

Local Class Names:

class Painter$1$Circle

class Painter$1$Map

Creating an instance of a non-static local class requires an instance of the enclosing class. In Example 8.10, the non-static method createCircle() is invoked on the instance of the enclosing class to create an instance of the non-static local class, as shown at (11). In the non-static method, the reference to the instance of the enclosing context is passed implicitly in the constructor call of the non-static local class at (6).

A static method can be invoked either through the class name or through a reference of the class type. An instance of a static local class can be created either way by calling the createMap() method, as shown at (12) and (13). As might be expected, no outer object is involved.

As references to a local class cannot be declared outside of the local context, the functionality of the class is only available through supertype references. The method draw() is invoked on objects in the array at (14). The program output indicates which objects were created. In particular, note that the final parameter radius of the method createCircle() at (4) is accessed by the draw() method of the local class Circle at (5). An instance of the local class Circle is created at (11) by a call to the method createCircle(). The draw() method is invoked on this instance of the local class Circle in the loop at (14). The value of the final parameter radius is still accessible to the draw() method invoked on this instance, although the call to the method createCircle(), which created the instance in the first place, has completed. Values of final local variables continue to be available to instances of local classes whenever these values are needed.

The output in Example 8.10 also shows the actual names of the local classes. In fact, the local class names are reflected in the class file names.

Another use of local classes is shown in Example 8.11. The code shows how local classes can be used, together with assertions, to implement certain kinds of postconditions (see Section 6.10, p. 275). The basic idea is that a computation wants to save or cache some data that is later required when checking a postconditon. For example, a deposit is made into an account, and we want to check that the transaction is valid after it is done. The computation can save the old balance before the transaction, so that the new balance can be correlated with the old balance after the transaction.

The local class Auditor at (2) acts as a repository for data that needs to be retrieved later to check the postcondition. Note that it accesses the final parameter, but declarations that follow its declaration would not be accessible. The assertion in the method check() at (4) ensures that the postcondition is checked, utilizing the data that was saved when the Auditor object was constructed at (5).

Example 8.11 Objects of Local Classes as Caches

class Account {

int balance;

/** (1) Method makes a deposit into an account. */

void deposit(final int amount) {

/** (2) Local class to save the necessary data and to check

that the transaction was valid. */

class Auditor {

/** (3) Stores the old balance. */

private int balanceAtStartOfTransaction = balance;

/** (4) Checks the postcondition. */

void check() {

assert balance - balanceAtStartOfTransaction == amount;

}

}

Auditor auditor = new Auditor(); // (5) Save the data.

balance += amount; // (6) Do the transaction.

auditor.check(); // (7) Check the postcondition.

}

public static void main(String[] args) {

Account ac = new Account();

ac.deposit(250);

}

}

Classes are usually first defined and then instantiated using the new operator. Anonymous classes combine the process of definition and instantiation into a single step. Anonymous classes are defined at the location they are instantiated, using additional syntax with the new operator. As these classes do not have a name, an instance of the class can only be created together with the definition.

An anonymous class can be defined and instantiated in contexts where a reference value can be used (i.e., as expressions that evaluate to a reference value denoting an object). Anonymous classes are typically used for creating objects on the fly in contexts such as the value in a return statement, an argument in a method call, or in initialization of variables. Typical uses of anonymous classes are to implement event listeners in GUI-based applications, threads for simple tasks (see examples in Chapter 13, p. 613), and comparators for providing a total ordering of objects (see Example 15.11, p. 774).

Like local classes, anonymous classes can be defined in static or non-static context. The keyword static is never used.

The following syntax can be used for defining and instantiating an anonymous class that extends an existing class specified by <superclass name>:

new <superclass name> (<optional argument list>) { <member declarations> }

Optional arguments can be specified, which are passed to the superclass constructor. Thus, the superclass must provide a constructor corresponding to the arguments passed. No extends clause is used in the construct. Since an anonymous class cannot define constructors (as it does not have a name), an instance initializer can be used to achieve the same effect as a constructor. Only non-static members and final static fields can be declared in the class body.

Example 8.12 Defining Anonymous Classes

interface IDrawable { // (1)

void draw();

}

//_______________________________________________________

class Shape implements IDrawable { // (2)

public void draw() { System.out.println("Drawing a Shape."); }

}

//_______________________________________________________

class Painter { // (3) Top-level Class

public Shape createShape() { // (4) Non-static Method

return new Shape(){ // (5) Extends superclass at (2)

public void draw() { System.out.println("Drawing a new Shape."); }

};

}

public static IDrawable createIDrawable() { // (7) Static Method

return new IDrawable(){ // (8) Implements interface at (1)

public void draw() {

System.out.println("Drawing a new IDrawable.");

}

};

}

}

//_______________________________________________________

public class AnonClassClient {

public static void main(String[] args) { // (9)

IDrawable[] drawables = { // (10)

new Painter().createShape(), // (11) non-static anonymous class

Painter.createIDrawable(), // (12) static anonymous class

new Painter().createIDrawable() // (13) static anonymous class

};

for (int i = 0; i < drawables.length; i++) // (14)

drawables[i].draw();

System.out.println("Anonymous Class Names:");

System.out.println(drawables[0].getClass());// (15)

System.out.println(drawables[1].getClass());// (16)

}

}

Output from the program:

Drawing a new Shape.

Drawing a new IDrawable.

Drawing a new IDrawable.

Anonymous Class Names:

class Painter$1

class Painter$2

Class declarations from Example 8.10 are adapted to use anonymous classes in Example 8.12. The non-static method createShape() at (4) defines a non-static anonymous class at (5), which extends the superclass Shape. The anonymous class overrides the inherited method draw().

// ...

class Shape implements IDrawable { // (2)

public void draw() { System.out.println("Drawing a Shape."); }

}

class Painter { // (3) Top-level Class

public Shape createShape() { // (4) Non-static Method

return new Shape() { // (5) Extends superclass at (2)

public void draw() { System.out.println("Drawing a new Shape."); }

};

}

// ...

}

// ...

As we cannot declare references of an anonymous class, the functionality of the class is only available through superclass references. Usually it makes sense to override methods from the superclass. Any other members declared in an anonymous class cannot be accessed directly by an external client.

The following syntax can be used for defining and instantiating an anonymous class that implements an interface specified by <interface name>:

new <interface name>() { <member declarations> }

An anonymous class provides a single interface implementation, and no arguments are passed. The anonymous class implicitly extends the Object class. Note that no implements clause is used in the construct. The class body has the same restrictions as previously noted for anonymous classes extending an existing class.

An anonymous class implementing an interface is shown below. Details can be found in Example 8.12. The static method createIDrawable() at (7) defines a static anonymous class at (8), which implements the interface IDrawable, by providing an implementation of the method draw(). The functionality of objects of an anonymous class that implements an interface is available through references of the interface type and the Object type (i.e., the supertypes).

interface IDrawable { // (1) Interface

void draw();

}

// ...

class Painter { // (3) Top-level Class

// ...

public static IDrawable createIDrawable() { // (7) Static Method

return new IDrawable(){ // (8) Implements interface at (1)

public void draw() {

System.out.println("Drawing a new IDrawable.");

}

};

}

}

// ...

The following code is an example of a typical use of anonymous classes in building GUI-applications. The anonymous class at (1) implements the ActionListener interface that has the method actionPerformed(). When the addActionListener() method is called on the GUI-button denoted by the reference quitButton, the anonymous class is instantiated and the reference value of the object is passed as a parameter to the method. The method addActionListener() of the GUI-button can use the reference value to invoke the method actionPerformed() in the ActionListener object.

quitButton.addActionListener(

new ActionListener() { // (1) Anonymous class implements an interface.

// Invoked when the user clicks the quit button.

public void actionPerformed(ActionEvent evt) {

System.exit(0); // (2) Terminates the program.

}

}

);

The discussion on instantiating local classes (see Example 8.10) is also valid for instantiating anonymous classes. The class AnonClassClient in Example 8.12 creates one instance at (11) of the non-static anonymous class defined at (5), and two instances at (12) and (13) of the static anonymous class defined at (8). The program output shows the polymorphic behavior and the runtime types of the objects. Similar to a non-static local class, an instance of a non-static anonymous class has an instance of its enclosing class at (11). An enclosing instance is not mandatory for creating objects of a static anonymous class, as shown at (12).

The names of the anonymous classes at runtime are also shown in the program output in Example 8.12. They are also the names used to designate their respective class files. Anonymous classes are not so anonymous after all.

Access rules for local classes (see Section 8.4, p. 372) also apply to anonymous classes. Example 8.13 is an adaptation of Example 8.9 and illustrates the access rules for anonymous classes. The local classes in Example 8.9 have been adapted to anonymous classes in Example 8.13. The TLCWithAnonClasses class has two methods, one non-static and the other static, which return an instance of a nonstatic and a static anonymous class, respectively. Both anonymous classes extend the Base class.

Anonymous classes can access final variables only in the enclosing context. Inside the definition of a non-static anonymous class, members of the enclosing context can be referenced using the <enclosing class name>.this construct. Non-static anonymous classes can also access any non-hidden members in the enclosing context by their simple names, whereas static anonymous classes can only access nonhidden static members.

Example 8.13 Accessing Declarations in Enclosing Context (Anonymous Classes)

class Base {

protected int nsf1;

}

//_______________________________________________________

class TLCWithAnonClasses { // Top level Class

private double nsf1; // Non-static field

private int nsf2; // Non-static field

private static int sf; // Static field

Base nonStaticMethod(final int fp) { // Non-static Method

final int flv = 10; // final local variable

final int hlv = 30; // final (hidden) local variable

int nflv = 20; // non-final local variable

return new Base() { // Non-static anonymous class

//static int f1; // (1) Not OK. Static members not allowed.

final static int f2 = 10; // (2) final static members allowed.

int f3 = fp; // (3) final param from enclosing method.

int f4 = flv; // (4) final local var from enclosing method.

//double f5 = nflv; // (5) Not OK. Only finals from enclosing method.

double f6 = nsf1; // (6) Inherited from superclass.

double f6a = this.nsf1; // (6a) Inherited from superclass.

double f6b = super.nsf1; // (6b) Inherited from superclass.

double f7 = TLCWithAnonClasses.this.nsf1; // (7) In enclosing object.

int f8 = nsf2; // (8) In enclosing object.

int f9 = sf; // (9) static from enclosing class.

int hlv; // (10) Hides local variable.

};

}

static Base staticMethod(final int fp) { // Static Method

final int flv = 10; // final local variable

final int hlv = 30; // final (hidden) local variable

int nflv = 20; // non-final local variable

return new Base() { // Static anonymous class

//static int f1; // (11) Not OK. Static members not allowed.

final static int f2 = 10; // (12) final static members allowed.

int f3 = fp; // (13) final param from enclosing method.

int f4 = flv; // (14) final local var from enclosing method.

//double f5 = nflv; // (15) Not OK. Only finals from enclosing method.

double f6 = nsf1; // (16 ) Inherited from superclass.

double f6a = this.nsf1; // (16a) Inherited from superclass.

double f6b = super.nsf1; // (16b) Inherited from superclass.

//double f7 = TLCWithAnonClasses.this.nsf1; //(17) No enclosing object.

//int f8 = nsf2; // (18) No enclosing object.

int f9 = sf; // (19) static from enclosing class.

int hlv; // (20) Hides local variable.

};

}

}

8.7 Which statement is true?

Select the one correct answer.

(a) Non-static member classes must have either default or public accessibility.

(b) All nested classes can declare static member classes.

(c) Methods in all nested classes can be declared static.

(d) All nested classes can be declared static.

(e) Static member classes can contain non-static methods.

8.8 Given the declaration

interface IntHolder { int getInt(); }

which of the following methods are valid?

//----(1)----

IntHolder makeIntHolder(int i) {

return new IntHolder() {

public int getInt() { return i; }

};

}

//----(2)----

IntHolder makeIntHolder(final int i) {

return new IntHolder {

public int getInt() { return i; }

};

}

//----(3)----

IntHolder makeIntHolder(int i) {

class MyIH implements IntHolder {

public int getInt() { return i; }

}

return new MyIH();

}

//----(4)----

IntHolder makeIntHolder(final int i) {

class MyIH implements IntHolder {

public int getInt() { return i; }

}

return new MyIH();

}

//----(5)----

IntHolder makeIntHolder(int i) {

return new MyIH(i);

}

static class MyIH implements IntHolder {

final int j;

MyIH(int i) { j = i; }

public int getInt() { return j; }

}

Select the two correct answers.

(a) The method labeled (1).

(b) The method labeled (2).

(c) The method labeled (3).

(d) The method labeled (4).

(e) The method labeled (5).

8.9 Which statements are true?

Select the two correct answers.

(a) No other static members, except final static fields, can be declared within a non-static member class.

(b) If a non-static member class is nested within a class named Outer, methods within the non-static member class must use the prefix Outer.this to access the members of the class Outer.

(c) All fields in any nested class must be declared final.

(d) Anonymous classes cannot have constructors.

(e) If objRef is an instance of any nested class within the class Outer, the expression (objRef instanceof Outer) will evaluate to true.

8.10 What will be the result of compiling and running the following program?

import java.util.Iterator;

class ReverseArrayIterator<T> implements Iterable<T>{

private T[] array;

public ReverseArrayIterator(T[] array) { this.array = array; }

public Iterator<T> iterator() {

return new Iterator<T>() {

private int next = array.length - 1;

public boolean hasNext() { return (next >= 0); }

public T next() {

T element = array[next];

next--;

return element;

}

public void remove() { throw new UnsupportedOperationException(); }

};

}

public static void main(String[] args) {

String[] array = { "Hi", "Howdy", "Hello" };

ReverseArrayIterator<String> ra = new ReverseArrayIterator<String>(array);

for (String str : ra) {

System.out.print("|" + str + "|");

}

}

}

Select the one correct answer.

(a) The program will fail to compile.

(b) The program will compile but throw an exception when run.

(c) The program will compile and print |Hi||Howdy||Hello|, when run.

(d) The program will compile and print |Hello||Howdy||Hi|, when run.

(e) The program will compile and print the strings in an unpredictable order, when run.

8.11 Which statement is true?

Select the one correct answer.

(a) Top-level classes can be declared static.

(b) Classes declared as members of top-level classes can be declared static.

(c) Local classes can be declared static.

(d) Anonymous classes can be declared static.

(e) No classes can be declared static.

8.12 Which expression can be inserted at (1) so that compiling and running the program will print LocalVar.str1?

public class Access {

final String str1 = "Access.str1";

public static void main(final String args[]) {

final String str1 = "LocalVar.str1";

class Helper { String getStr1() { return str1; } }

class Inner {

String str1 = "Inner.str1";

Inner() {

System.out.println( /* (1) INSERT EXPRESSION HERE */ );

}

}

Inner inner = new Inner();

}

}

Select the one correct answer.

(a) str1

(b) this.str1

(c) Access.this.str1

(d) new Helper().getStr1()

(e) this.new Helper().getStr1()

(f) Access.new Helper().getStr1()

(g) new Access.Helper().getStr1()

(h) new Access().new Helper().getStr1()

8.13 What will be the result of compiling and running the following program?

public class TipTop {

static final Integer i1 = 1;

final Integer i2 = 2;

Integer i3 = 3;

public static void main(String[] args) {

final Integer i4 = 4;

Integer i5 = 5;

class Inner {

final Integer i6 = 6;

Integer i7 = 7;

Inner () {

System.out.print(i6 + i7);

}

}

}

}

Select the one correct answer.

(a) The program will fail to compile.

(b) The program will compile but throw an exception when run.

(c) The program will compile and print 67, when run.

(d) The program will compile and print 13, when run.

(e) The program will compile but will not print anything, when run.

8.14 Which expressions, when inserted at (1), will result in compile-time errors?

public class TopLevel {

static final Integer i1 = 1;

final Integer i2 = 2;

Integer i3 = 3;

public static void main(String[] args) {

final Integer i4 = 4;

Integer i5 = 5;

class Inner {

final Integer i6 = 6;

Integer i7 = 7;

Inner (final Integer i8, Integer i9) {

System.out.println(/* (1) INSERT EXPRESSION HERE */);

}

}

new Inner(8, 9);

}

}

Select the three correct answers.

(a) i1

(b) i2

(c) i3

(d) i4

(e) i5

(f) i6

(g) i7

(h) i8

(i) i9

The following information was included in this chapter:

• categories of nested classes: static member classes and interfaces, non-static member classes, local classes, anonymous classes

• discussion of salient aspects of nested classes and interfaces:

• the context in which they can be defined

• which accessibility modifiers are valid for such classes and interfaces

• whether an instance of the enclosing context is associated with an instance of the nested class

• which entities a nested class or interface can access in its enclosing contexts

• whether both static and non-static members can be defined in a nested class

• importing and using nested classes and interfaces

• instantiating non-static member classes using <enclosing object reference>.new syntax

• accessing members in the enclosing context of inner classes using <enclosing class name>.this syntax

• accessing members both in the inheritance hierarchy and the enclosing context of nested classes

• implementing anonymous classes by extending an existing class or by implementing an interface

8.1 Create a new program with a nested class named PrintFunc that extends class Print from Exercise 7.2, p. 350. In addition to just printing the value, class PrintFunc should first apply a Function object on the value. The class PrintFunc should have a constructor that takes an instance of Function type as a parameter. The evaluate() method of the class PrintFunc should use the Function object on its argument. The evaluate() method should print and return the result. The evaluate() method in superclass Print should be used to print the value.

The program should behave like the one in Exercise 7.2, p. 350, but this time use the nested class PrintFunc instead of class Print.