Chapter 2

Framework of Financial Accounting Concepts and Standards: A Historical Perspective

2.1 Financial Accounting and Reporting

(b) Management Accounting and Tax Accounting

2.2 Why We Have a Conceptual Framework

(a) Special Committee on Cooperation with Stock Exchanges

(i) “Accepted Principles of Accounting.”

(b) Committee on Accounting Procedure, 1938–1959

(i) No Comprehensive Statement of Principles by the Institute

(ii) Accounting Research Bulletins

(iii) Failure to Reduce the Number of Alternative Accounting Methods

(c) Accounting Principles Board—1959–1973

(ii) The Accounting Principles Board, the Investment Credit, and the Seidman Committee

(iii) End of the Accounting Principles Board

(d) Financial Accounting Standards Board Faces Defining Assets and Liabilities

(i) Were They Assets? Liabilities?

(ii) Nondistortion, Matching, and What-You-May-Call-Its

(iii) An Overdose of Matching, Nondistortion, and What-You-May-Call-Its

(iv) Initiation of the Conceptual Framework

2.3 Financial Accounting Standards Board's Conceptual Framework

(a) Framework as a Body of Concepts

(i) Information Useful in Making Investment, Credit, and Similar Decisions

(ii) Representations of Things and Events in the Real-World Environment

(iii) Assets (and Liabilities)—Fundamental Element(s) of Financial Statements

(iv) Functions of the Conceptual Framework

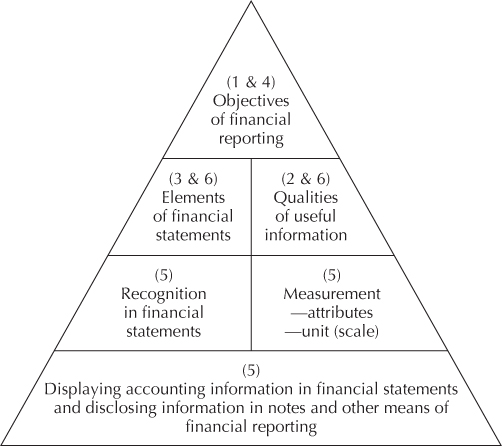

(b) Financial Accounting Standards Board Concepts Statements

(i) Objectives of Financial Reporting

(ii) Qualitative Characteristics of Accounting Information

(iii) Elements of Financial Statements

(iv) Recognition and Measurement

(v) Using Cash Flow Information and Present Value in Accounting Determinations

2.5 Sources and Suggested References

2.1 Financial Accounting and Reporting

The principal role of financial accounting and reporting is to serve the public interest by providing information that is useful in making business and economic decisions. That information facilitates the efficient functioning of capital and other markets, thereby promoting the efficient and equitable allocation of scarce resources in the economy. To undertake and fulfill that role, financial accounting in the twentieth century has evolved from a profession relying almost exclusively on the experience of a handful of illustrious practitioners into one replete with a set of financial accounting standards and an underlying conceptual foundation.

An underlying structure of accounting concepts was deemed necessary to provide to the institutions entrusted with setting accounting principles or standards the requisite tools for resolving accounting problems. Financial accounting now has a foundation of fundamental concepts and objectives in the Financial Accounting Standards Board's (FASB) Conceptual Framework for Financial Accounting and Reporting, which is intended to provide a basis for developing the financial accounting standards that are promulgated to guide accounting practice.

The FASB's conceptual framework and its antecedents constitute the major subject matter of this chapter. Some significant terms, organizations, and authoritative pronouncements need to be identified or briefly introduced. They already may be familiar to most readers or will become so in due course.

(a) Financial Accounting Standards Board and General Purpose External Financial Accounting and Reporting

Financial accounting and reporting is the familiar name of the branch of accounting whose precise but somewhat imposing full proper name is general-purpose external financial accounting and reporting. It is the branch of accounting concerned with general-purpose financial statements of business enterprises and not-for-profit organizations. General-purpose financial statements are possible because several groups, such as investors, creditors, and other resource providers, have common interests and common information needs. General-purpose financial reporting provides information to users who are outside a business enterprise or not-for-profit organization and lack the power to require the entity to supply the accounting information they need for decision making; therefore, they must rely on information provided to them by the entity's management. Other groups, such as taxing authorities and rate regulators, have specialized information needs but also the authority to require entities to provide the information they specify.

General-purpose external financial reporting is the sphere of authority of the FASB, the private-sector organization that since 1973 has established generally accepted accounting principles in the United States. General-purpose external financial accounting and reporting provides information that is based on generally accepted accounting principles and is audited by independent certified public accountants (CPAs). Generally accepted accounting principles result and have resulted primarily from the authoritative pronouncements of the FASB and its predecessors.

The FASB's standards pronouncements—Statements of Financial Accounting Standards (often abbreviated FASB Statement, SFAS, or FAS) and FASB Interpretations (often abbreviated FIN)—are recognized as authoritative by both the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) and the American Institute of Certified Public Accountants (AICPA).

The FASB succeeded the Accounting Principles Board (APB), whose authoritative pronouncements were the APB Opinions. In 1959 the APB had succeeded the Committee on Accounting Procedure, whose authoritative pronouncements were the Accounting Research Bulletins (often abbreviated ARB), some of which were designated as Accounting Terminology Bulletins (often abbreviated ATB).

With respect to the long name general-purpose external financial reporting, this chapter does what the standards-setting bodies also have done: For convenience, it uses the shortcut term financial reporting.

(b) Management Accounting and Tax Accounting

Financial accounting and reporting is only part of the broad field of accounting. Other significant kinds of accounting include management accounting and tax accounting.

Management accounting is internal accounting designed to meet the information needs of managers. Although the same accounting system usually accumulates, processes, and disseminates both management and financial accounting information, managers' responsibilities for making decisions and planning and controlling operations at various administrative levels of a business enterprise or not-for-profit organization require more detailed information than is considered necessary or appropriate for external financial reporting. Management accounting includes information that is normally not provided outside an organization and is usually tailored to meet specific management information needs.

Tax accounting is concerned with providing appropriate information needed by individuals, corporations, and others for preparing the various returns and reports required to comply with tax laws and regulations, especially the Internal Revenue Code. It is significant in the administration of domestic tax laws, which are to a large extent self-assessing. Tax accounting is based generally on the same procedures that apply to financial reporting. There are some significant differences, however, and taxing authorities have the statutory power to prescribe the specific information they want taxpayers to submit as a basis for assessing the amount of income tax owed and do not need to rely on information provided to other groups.

2.2 Why We Have a Conceptual Framework

“Accounting principles” has proven to be an extraordinarily elusive term. To the nonaccountant (as well as to many accountants) it connotes things basic and fundamental, of a sort which can be expressed in few words, relatively timeless in nature, and in no way dependent upon changing fashions in business or the evolving needs of the investment community.

The Wheat Report

Principle. A general law or rule adopted or professed as a guide to action; a settled ground or basis of conduct or practice.

Accounting Research Bulletin No. 7

A recurring theme in financial accounting in the United States in the twentieth century has been the call for a comprehensive, authoritative statement of basic accounting principles. It has reflected a widespread perception that something more fundamental than rules or descriptions of methods or procedures was needed to form a basis for, explain, or govern financial accounting and reporting practice. A number of organizations, committees, and individuals in the profession have developed or attempted to develop their own variations of what they have diversely called principles, standards, conventions, rules, postulates, or concepts. Those efforts met with varying degrees of success, but by the 1970s none of the codifications or statements had come to be accepted or relied on in practice as the definitive statement of accounting's basic principles.

The pursuit of a statement of accounting principles has reflected two distinct schools of thought: that accounting principles are generalized or drawn from practice without reference to a systematic theoretical foundation or that accounting principles are based on a few fundamental premises that together with the principles provide a framework for solving specific problems encountered in practice. Early efforts to codify or develop accounting principles were dominated by the belief that principles are essentially a “distillation of experience,” a description generally attributed to George O. May, one of the most influential accountants of his time, who used it in the title of a book, Financial Accounting: A Distillation of Experience.1 However, as accounting has matured and its role in society has increased, momentum in developing accounting principles has shifted to those accountants who have come to understand what has been learned in many other fields: that reliance on experience alone leads only so far because environments and problems change; that until knowledge gained through experience is given purpose, direction, and internal consistency by a conceptual foundation, fundamentals will be endlessly reargued and practice blown in various directions by the winds of changing perceptions and proliferating accounting methods; and that only by studying and understanding the foundations of practices can the path of progress be discovered and the hope of improving practice be realized.

The conceptual framework project of the FASB represents the most comprehensive effort thus far to establish a structure of objectives and fundamentals to underlie financial accounting and reporting practice. To understand what it is, how it came about, and why it took the form and included the concepts that it did requires some knowledge of its antecedents, which extend back more than 60 years.

(a) Special Committee on Cooperation with Stock Exchanges

The origin of the use of principle in financial accounting and reporting can be traced to a special committee of the American Institute of Accountants (American Institute of Certified Public Accountants since 1957). The Special Committee on Cooperation with Stock Exchanges, chaired by George O. May, gave the word special significance in the attest function of accountants. That significance is still evident in audit reports signed by members of the Institute and most other CPAs attesting that the financial statements of their clients present fairly, or do not present fairly, the client's financial position, results of operations, and cash flows “in conformity with generally accepted accounting principles.” The committee laid the foundation that has been the basis of both subsequent progress in identifying or developing and enunciating accounting principles and many of the problems that have accompanied the resulting principles.

In 1930 the Institute undertook a cooperative effort with the New York Stock Exchange aimed at improving financial disclosure by publicly held enterprises. It was widely believed that inferior accounting and reporting practices had contributed to the stock market decline and depression that began in 1929. The Exchange was concerned that its listed companies were using too many different accounting and reporting methods to reflect similar transactions and that some of those methods were questionable. The Institute wanted to make financial statements more informative and authoritative, to clarify the authority and responsibility of auditors, and to educate the public about the conventional nature of accounting and the limitations of accounting reports.

The Exchange's Committee on Stock List and the Institute's Special Committee on Cooperation with Stock Exchanges exchanged correspondence between 1932 and 1934. The special committee's report, comprising a series of letters that passed between the two committees, was issued to Institute members in 1934 under the title Audits of Corporate Accounts (reprinted in 1963). The key part was a letter dated September 22, 1932, from the Institute committee.

(i) “Accepted Principles of Accounting.”

The special committee recommended that an authoritative statement of the broad accounting principles on which “there is a fairly general agreement” be formulated in consultation with a small group of qualified persons, including accountants, lawyers, and corporate officials. Within that framework of “accepted principles of accounting,” each company would be free to choose the methods and procedures most appropriate for its financial statements, subject to requirements to disclose the methods it was using and to apply them consistently. Audit certificates (reports) for listed companies would state that their financial statements were prepared in accordance with “accepted principles of accounting.” The special committee anticipated that its program would improve financial reporting because disclosure would create pressure from public opinion to eliminate less-desirable practices.

The special committee did not define “principles of accounting,” but it illustrated what it had in mind. It gave two explicit examples of accepted broad principles of accounting:

It is a generally accepted principle that plant value should be charged against gross profits over the useful life of the plant….

Again, the most commonly accepted method of stating inventories is at cost or market, whichever is lower.2

It also listed five principles that it presumed would be included in the contemplated statement of “broad principles of accounting which have won fairly general acceptance”:

1. Unrealized profit should not be credited to income account of the corporation either directly or indirectly, through the medium of charging against such unrealized profits amounts, which would ordinarily fall to be charged against income account. Profit is deemed to be realized when a sale in the ordinary course of business is affected, unless the circumstances are such that the collection of the sale price is not reasonably assured. An exception to the general rule may be made [for industries in which trade custom is to take inventories at net selling prices, which may exceed cost].

2. Capital surplus [other paid-in capital], however created, should not be used to relieve the income account of the current or future years of charges, which would otherwise fall to be made there against. This rule might be subject to the exception that [permits use of quasi-reorganization].

3. Earned surplus [retained earnings] of a subsidiary company created prior to acquisition does not form a part of the consolidated earned surplus of the parent company and subsidiaries; nor can any dividend declared out of such surplus properly be credited to the income account of the parent company.

4. While it is perhaps in some circumstances permissible to show stock of a corporation held in its own treasury as an asset, if adequately disclosed, the dividends on stock so held should not be treated as a credit to the income account of the company.

5. Notes or accounts receivable due from officers, employees, or affiliated companies must be shown separately and not included under a general heading such as Notes Receivable or Accounts Receivable.3

The Institute submitted the committee's five principles for acceptance by its members in 1934, and they are now in ARB No. 43, Restatement and Revision of Accounting Research Bulletins (issued 1953), Chapter .1A, “Rules Adopted by Membership” [paragraphs 1–5].

The special committee's use of the word principle set the stage not only for the Institute's efforts to identify “accepted principles of accounting” but also for future confusion and controversy over what accountants mean when they use the word principle.

But Were They “Principles”?.

The special committee's examples of broad principles of accounting were much less fundamental, timeless, and comprehensive than what most people perceive to be principles. They had little or nothing in them that made them more basic or less concrete than conventions or rules. Moreover, the special committee itself referred to them as rules in describing exceptions to them, the Institute characterized them as rules in submitting them for approval by its members, and the chairman of the special committee later conceded that they were nothing more than rules:

When the committee…undertook to lay down some of the basic principles of modern accounting, it found itself unable to suggest more than half a dozen which could be regarded as generally acceptable, and even those were rules rather than principles, and were, moreover, admittedly subject to exception.4

Not surprisingly, the special committee's use of the word principles was soon challenged. In a contest sponsored by the Institute for its fiftieth anniversary celebration in 1937, Gilbert R. Byrne's essay entitled “To What Extent Can the Practice of Accounting Be Reduced to Rules and Standards?” won first prize for the best answer to the question posed in the title. He complained about accountants' propensity to downgrade principle by equating it with terms such as rule, convention, and procedure.

[R]ecent discussions have used the term “accounting principles” to cover a conglomeration of accounting practices, procedures, conventions, etc.; many, if not most, so-called principles may merely have to do with methods of presenting items on financial statements or technique of auditing, rather than matters of fundamental accounting principle.5

Stephen Gilman made the same point in his careful analysis of terms in five chapters of his book, Accounting Concepts of Profit.

With sublime disregard of lexicography, accountants speak of “principles,” “tenets,” “doctrines,” “rules,” and “conventions” as if they were synonymous.6

Gilman also quoted an excerpt from the Century Dictionary that he thought pertinent “because of the confusion noted in some accounting writings [about] the distinction between ‘principle’ and ‘rule’ ”:

There are no two words in the English language used so confusedly one for the other as the words rule and principle. You can make a rule; you cannot make a principle; you can lay down a rule; you cannot, properly speaking, lay down a principle. It is laid down for you. You can establish a rule; you cannot, properly speaking, establish a principle. You can only declare it. Rules are within your power, principles are not. A principle lies back of both rules and precepts; it is a general truth, needing interpretation and application to particular cases.7

Byrne, Gilman, and others pointed out that the form of accountant's report recommended by the special committee made accountants look foolish by requiring them to express opinions based on the existence of principles they actually could not specify. In that form of report, an accountant expressed the opinion that a client's financial statement is “fairly present, in accordance with accepted principles of accounting consistently maintained by the company during the year under review, its position…and the results of its operations.” According to Byrne, that opinion presumed that accepted principles of accounting actually existed and accountants in general knew and agreed on what they were. In fact, “While there have been several attempts to enumerate [those principles], to date there has been no statement upon which there has been general agreement.”8

That diagnosis was confirmed by Gilman as well as by Howard C. Greer:

…the entire body of precedent [the “accepted principles of accounting”] has been taken for granted.

It is as though each accountant felt that while he himself had never taken the time or the trouble to make an actual list of accounting principles, he was comfortably certain that someone else had done so….

[T]he accountants are in the unenviable position of having committed themselves in their certificates [reports] as to the existence of generally accepted accounting principles while between themselves they are quarreling as to whether there are any accounting principles and if there are how many of them should be recognized and accepted.9

There is something incongruous about the outpouring of thousands of accountants' certificates [reports] which refer to accepted accounting principles, and a situation in which no one can discover or state what those accepted accounting principles are. The layman cannot understand.10

Byrne argued that lack of agreement on what constituted accepted accounting principles resulted “in large part because there is no clear distinction, in the minds of many, between that body of fundamental truths underlying the philosophy of accounts which are properly thought of as principles, and the larger body of accounting rules, practices, and conventions which derive from principles, but which of themselves are not principles.”11 His prescription for accountants was to use principle in its most commonly understood sense of being more fundamental and enduring than rules and conventions.

If accounting, as an organized body of knowledge, has validity, it must rest upon a body of principles, in the sense defined in Webster's New International Dictionary:

“A fundamental truth; a comprehensive law or doctrine, from which others are derived, or on which others are founded; a general truth; an elementary proposition or fundamental assumption; a maxim; an axiom; a postulate.” …

Accounting principles, then, are the fundamental concepts on which accounting, as an organized body of knowledge, rests…. [T]hey are the foundation upon which the superstructure of accounting rules, practices and conventions is built.12

Gilman, in contrast, could find no principles that fit Byrne's definition. He concluded that most, if not all, of the propositions that had been put forth as principles of accounting should be relabeled “as doctrines, conventions, rules, or mere statements of opinion.”13 He called on accountants to admit that there were no accounting principles in the fundamental sense and to waste no more time and effort on attempts to identify and state them.

May's Attempts to Rectify “Considerable Misunderstanding.”.

In several articles and a book, George O. May responded to those and other criticisms of “accounting principles” and explained what the special committee, as well as several other Institute committees of which he was chairman, had done and why. He detected, in the criticisms and elsewhere, what he described as “considerable misunderstanding” of both the nature of financial accounting and the committees' work on accounting principles and thought it necessary to get the matter back on the right track.

Although he acknowledged that “in the correspondence the [special] Committee had used the words ‘rules,’ ‘methods,’ ‘conventions,’ and ‘principles’ interchangeably,”14 May considered questions such as whether the propositions should be called rules or principles not to be matters “of any real importance.” As Byrne had pointed out, if there were any principles that fit his definition, “they must be few in number and extremely general in character (such as ‘consistency’ and ‘conservatism’).”15 Thus, they would afford less precise guidance than the more concrete principles illustrated by the special committee. Those who scolded the special committee for misusing “principles” had apparently forgotten that “accounting rules and principles are founded not on abstract theories or logic, but on utility.”16

May urged the profession and others to focus efforts to improve financial accounting, as had the special committee, on the questions “of real importance”—the consequences of the necessarily conventional nature of accounting and the limitations of accounting reports. He explained the philosophy underlying the recommendation of the special committee and summarized that philosophy in the introductory pages of his book:

In 1926,…I decided to relinquish my administrative duties and devote a large part of my time to consideration of the broader aspects of accounting. As a result of that study I became convinced that a sound accounting structure could not be built until misconceptions had been cleared away, and the nature of the accounting process and the limitations on the significance of the financial statements which it produced were more frankly recognized.

It became clear to me that general acceptance of the fact that accounting was utilitarian and based on conventions (some of which were necessarily of doubtful correspondence with fact) was an indispensable preliminary to real progress….

Many accountants were reluctant to admit that accounting was based on nothing of a higher order of sanctity than conventions. However, it is apparent that this is necessarily true of accounting as it is, for instance, of business law. In these fields there are no principles, in the fundamental sense of that word, on which we can build; and the distinctions between laws, rules, standards, and conventions lie not in their nature but in the kind of sanctions by which they are enforced. Accounting procedures have in the main been the result of common agreement between accountants.17

He also reiterated and amplified a number of points the special committee had emphasized in Audits of Corporate Accounts concerning what the investing public already knew or should understand about financial accounting and reporting, such as, that because the value of a business depended mainly on its earning capacity, the income statement was more important than the balance sheet and should indicate to the fullest extent possible the earning capacity of the business during the period on which it reported; that because the balance sheet of a large modern corporation was to a large extent historical and conventional, largely comprising the residual amounts of expenditures or receipts after first determining a proper charge or credit to the income account for the year, it did not, and should not be expected to, represent an attempt to show the present values of the assets and liabilities of the corporation; and that because financial accounting and reporting was necessarily conventional, some variety in accounting methods was inevitable.

Special Committee's Definition of Principle.

May not only identified the definition of principle the special committee had used but also explained why it had chosen that particular meaning. In his comment on Byrne's essay, he recalled the committee's discussion and searching of dictionaries before choosing the “perhaps rather magniloquent word ‘principle’…in preference to the humbler ‘rule.’ ” The definition of “principle” in the Oxford English Dictionary that came closest to defining the sense in which the special committee used the word was the seventh definition:

A general law or rule adopted or professed as a guide to action; a settled ground or basis of conduct or practice.

The time and effort spent in searching dictionaries was fruitful—the committee found exactly the definition for which it was looking:

[The]…sense of the word “principle” above quoted seemed…to fit the case perfectly. Examination of the report as a whole will make clear what the committee contemplated; namely, that each corporation should have a code of “laws or rules, adopted or professed, as a guide to action,” and that the accountants should report, first, whether this code conformed to accepted usages, and secondly, whether it had been consistently maintained and applied.18

Thus, the special committee opted for the lofty principle rather than the more precise rule or convention because the definition that best fit the committee's needs was a definition of principle, albeit an obscure one, not a definition of rule or convention. Moreover, rule and convention carried unfortunate baggage:

[The] word “rules” implied the existence of a ruling body which did not exist; the word “convention” was regarded as not appropriate for popular use and in the opinion of some would not convey an adequate impression of the authority of the precepts by which the accounts were judged.19

Principle, however, conveyed desirable implications:

It used to be not uncommon for the accountant who had been unable to persuade his client to adopt the accounting treatment that he favored, to urge as a last resort that it was called for by “accounting principles.” Often he would have had difficulty in defining the “principle” and saying how, why, and when it became one. But the method was effective, especially in dealing with those (of whom there were many) who regarded accounting as an esoteric but well established body of learning and chose to bow to its authority rather than display their ignorance of its rules. Obviously, the word “principle” was an essential part of the technique; “convention” would have been quite ineffective.20

Rules were elevated into principles because the committee thought it necessary to use a word with the force or power of principle to prevent the auditor's authority from being lost on the client.

(ii) The Best-Laid Schemes

The special committee's program focused on what individual listed companies and their auditors would do. Each corporation would choose from “accepted principles of accounting” its own code of “laws or rules, adopted or professed, as a guide to action” and within that framework would be free to choose the methods and procedures most appropriate for its financial statements but would disclose the methods it was using and would apply them consistently. An auditor's report would include an opinion on whether or not each corporation's code consisted of accepted principles of accounting and was applied consistently. The Stock Exchange would enforce the program by requiring each listed corporation to comply in order to keep its listing.

The Institute was to sponsor or lead an effort in which accountants, lawyers, corporate officials, and other “qualified persons” would formulate a statement of “accepted principles of accounting” to guide listed companies and auditors, but it was not to get into the business of specifying those principles. The special committee had explicitly considered and rejected “the selection by competent authority out of the body of acceptable methods in vogue today [the] detailed sets of rules which would become binding on all corporations of a given class.” The special committee also had avoided using rule because the word implied a rule-setting body that did not exist, and it had no intention of imposing on anyone what it considered to be an unnecessary and impossible burden. “Within quite wide limits, it is relatively unimportant to the investor what precise rules or conventions are adopted by a corporation in reporting its earnings if he knows what method is being followed and is assured that it is followed consistently from year to year.”21 Moreover, the committee felt that no single body could adequately assess and allow for the varying characteristics of individual corporations, and the choice of which detailed methods best fit a corporation's circumstances thus was best left to each corporation and its auditors. Because financial accounting was essentially conventional and required estimates and allocations of costs and revenues to periods, the utility of the resulting financial statements inevitably depended significantly on the competence, judgment, and integrity of corporate management and independent auditors. Although there had been a few instances of breach of trust or abuse of investors, the committee had confidence in the trustworthiness of the great majority of those responsible for financial accounting and reporting.

In the end, the special committee's recommendations were never fully implemented. Nonaccountants were not invited to participate in developing a statement of accepted accounting principles. In fact, although the Institute submitted the special committee's five principles for acceptance by its members, it attempted no formulation of a statement of broad principles, even by accountants. Nor did the Exchange require its listed companies to disclose their accounting methods.

Special Committee's Heritage.

The only recommendation to survive was that each company should be permitted to choose its own accounting methods within a framework of “accepted principles of accounting.” The committee's definition of principle also survived, and “accepted principles of accounting” became “generally accepted.”

The special committee's definition of principle—“A general law or rule adopted or professed as a guide to action; a settled ground or basis of conduct or practice”—was incorporated verbatim in Accounting Research Bulletin No. 7, Report of the Committee on Terminology (George O. May, chairman), in 1940, but it was attributed to the New English Dictionary rather than to the Oxford English Dictionary. When ARB 1–42 were restated and revised in 1953, the same definition of “principle,” by then attributed only to “Dictionaries,” was carried over to Accounting Terminology Bulletin No. 1, Review and Résumé.

“Generally” was added to the special committee's “accepted principles of accounting” in Examination of Financial Statements by Independent Public Accountants, published by the Institute in 1936 as a revision of an auditing publication, Verification of Financial Statements (1929). According to its chairman, Samuel J. Broad, the revision committee inserted “generally” to answer questions such as “…accepted by whom? business? professional accountants? the SEC? I heard of one accountant who claimed that if a principle was accepted by him and a few others it was ‘accepted.’ ”22

In retrospect, the legacy of institutionalizing that definition of principle has been that the terms principle, rule, convention, procedure, and method have been used interchangeably, and imprecise and inconsistent usage has hampered the development and acceptance of subsequent efforts to establish accounting principles. Moreover, within the context of so broad a definition of principle, the combination of the latitude given management in choosing accounting methods, the failure to incorporate into financial accounting and reporting the discipline that would have been imposed by the profession's adopting a few, broad, accepted accounting principles, and the failure to enforce the requirement that companies disclose their accounting methods gave refuge to the continuing use of many different methods and procedures, all justified as “generally accepted principles of accounting,” and encouraged the proliferation of even more “generally accepted” accounting methods.

Finally, despite the reluctance of the Institute to become involved in setting principles or rules, it eventually assumed that responsibility after the U.S. SEC was created.

(iii) Securities Acts and the Securities and Exchange Commission—“Substantial Authoritative Support.”

The Securities Exchange Act of 1934 established the SEC and gave it authority to prescribe accounting and auditing practices to be used by companies in the financial reports required of them under that Act and the Securities Act of 1933. The SEC, like the Stock Exchange before it, became increasingly concerned about the variety of accounting practices approved by auditors. Carman G. Blough, first Chief Accountant of the SEC, told a round-table session at the Institute's fiftieth anniversary celebration in 1937 that unless the profession took steps to develop a set of accounting principles and reduce the areas of difference in accounting practice, “the determination of accounting principles and methods used in reports to the Commission would devolve on the Commission itself. The message to the profession was clear and unambiguous.”23

In April 1938, the Chief Accountant issued Accounting Series Release (ASR) No. 4, Administrative Policy on Financial Statements, requiring registrants to use only accounting principles having “substantial authoritative support.” That made official and reinforced Blough's earlier message: If the profession wanted to retain the ability to determine accounting principles and methods, the Institute would have to issue statements of principles that could be deemed to have “substantial authoritative support.” Through ASR 4, the Commission reserved the right to say what had “substantial authoritative support” but also opened the way to give that recognition to recommendations on principles issued by the Institute.

(b) Committee on Accounting Procedure, 1938–1959

The Institute expanded significantly its Committee on Accounting Procedure (not principles) and gave it responsibility for accounting principles and authority to speak on them for the Institute—to issue pronouncements on accounting principles without the need for approval of the Institute's membership or governing Council. The committee was intended to be the principal source of the “substantial authoritative support” for accounting principles sought by the SEC.

The president of the Institute was the nominal chairman of the Committee on Accounting Procedure. Its vice chairman and guiding spirit was George O. May.

(i) No Comprehensive Statement of Principles by the Institute

The course the committee would follow for the next 20 years was set at its initial meeting in January 1939. Carman G. Blough, who had left the Commission and become a partner of Arthur Andersen & Co. and who was a member of the committee, recounted in a paper at a symposium at the University of California at Berkeley in 1967 how the committee chose its course:

At first it was thought that a comprehensive statement of accounting principles should be developed which would serve as a guide to the solution of the practical problems of day to day practice….

After extended discussion it was agreed that the preparation of such a statement might take as long as five years. In view of the need to begin to reduce the areas of differences in accounting procedures before the SEC lost patience and began to make its own rules on such matters, it was concluded that the committee could not possibly wait for the development of such a broad statement of principles.24

The committee thus decided that the need to deal with particular problems was too pressing to permit it to spend time and effort on a comprehensive statement of principles.

Statements of Accounting Principles by Others.

Although the Institute attempted no formulation of a statement of broad accounting principles, two other organizations did. Both statements were written by professors, and each was an early representative of one of the two schools of thought about the nature and derivation of accounting principles.

American Accounting Association's Theoretical Basis for Accounting Rules And Procedures

“A Tentative Statement of Accounting Principles Underlying Corporate Financial Statements,” by the Executive Committee of the American Accounting Association (AAA) in 1936, was based on the assumption “that a corporation's periodic financial statements should be continuously in accord with a single coordinated body of accounting theory.”25 The phrase Accounting Principles Underlying Corporate Financial Statements emphasized that improvement in accounting practice could best be achieved by strengthening the theoretical framework that supported practice. The “Tentative Statement” was almost completely ignored by the Institute, and its effect on accounting practice at the time was minimal. However, two of its principles (one a corollary of the other) and a monograph by W. A. Paton and A. C. Littleton based on it proved to have long-lasting influence and are described shortly.

Sanders, Hatfield, and Moore's Codification of Accounting Practices

In contrast to the AAA's attempt to derive a coordinated body of accounting theory, A Statement of Accounting Principles, by Thomas Henry Sanders, Henry Rand Hatfield, and Underhill Moore, two professors of accounting and a professor of law, respectively, was a compilation through interviews, discussions, and surveys of “the current practices of accountants” and reflected no systematic theoretical foundation. It was prepared under sponsorship of the Haskins & Sells Foundation and was published in 1938 by the Institute, which distributed it to all Institute members as “a highly valuable contribution to the discussion of accounting principles.”

The report was excoriated for its virtually exclusive reliance on experience and current practice as the basis for principles, its reluctance to criticize even the most dubious practices, and its implication that accountants had no greater duty than to ratify whatever management wanted to do with its accounting as long as what it did was legal and properly disclosed. Many, perhaps most, of the characteristics criticized were inherent in what the authors were asked to do—formulate a code of accounting principles based on practice and the weight of opinion and authority. Even so, the report tended to strike a dubious balance between auditors' independence and duty to exercise professional judgment on the one hand and their deference to management on the other.

It was, nevertheless, “the first relatively complete statement of accounting principles and the only complete statement reflecting the school of thought that accounting principles are found in what accountants do.” It was a successful attempt to codify the methods and procedures that accountants used in everyday practice and “was in fact a ‘distillation of practice.’ ”26 Moreover, since the Committee on Accounting Procedure adopted and pursued the same view of principles and incorporated existing practice and the weight of opinion and authority in its pronouncements, A Statement of Accounting Principles probably was a good approximation of what the committee would have produced had it attempted to codify existing “accepted principles of accounting.”

Sets of Principles by Individuals

Three less ambitious efforts in 1937 and 1938—eight principles in Gilbert R. Byrne's prize-winning essay,27 nine accounting principles and conventions in D. L. Trouant's book Financial Audits,28 and six accounting principles in A. C. Littleton's “Tests for Principles”29—provided examples, rather than complete statements, of principles. Each described what principles meant and gave some propositions to illustrate the nature of principles or to show how propositions could be judged to be accepted principles. The resulting principles were substantially similar to those of the special committee. For example, all three authors included the conventions that revenue usually should be realized (recognized) at the time of sale and that cost of plant should be depreciated over its useful life. An interesting exception was Trouant's first principle—“Everything having a value has a claimant”—and the accompanying explanation: “In this axiom lies the basis of double-entry bookkeeping and from it arises the equivalence of the balance-sheet totals for assets and liabilities.”30 That proposition not only was more fundamental than most principles of the time but also was distinctive in referring to the world in which accounting takes place rather than to the accounting process.

Principles from Resolving Specific Problems.

None of those five efforts to state principles of accounting seems to have had much effect on practice, although Sanders, Hatfield, and Moore's A Statement of Accounting Principles may indirectly have affected the decision of the Committee on Accounting Procedure to tackle specific accounting problems first: “[A]nyone who read it could not fail to be impressed with the wide variety of procedures that were being followed in accounting for similar transactions and in that way undoubtedly it helped to point up the need for doing something to standardize practices.”31

In any event, the Committee on Accounting Procedure decided that to formulate a statement of broad accounting principles would take too long and elected instead to use a problem-by-problem approach in which the committee would recommend one or more alternative procedures as preferable to other alternatives for resolving a particular financial accounting or reporting problem. The decision to resolve pressing and controversial matters that way was described by members of the committee as “a decision to put out the brush fires before they created a conflagration.”32

(ii) Accounting Research Bulletins

The committee's means of extinguishing the threatening fires were the ARB. From September 1939 through August 1959 it issued 51 ARBs on a variety of subjects. Among the most important or most controversial (or both) were No. 2, Unamortized Discount and Redemption Premium on Bonds Refunded (1939); No. 23, Accounting for Income Taxes (1944); No. 24, Accounting for Intangible Assets (1944); No. 29, Inventory Pricing (1947); No. 32, Income and Earned Surplus [Retained Earnings] (1947); No. 33, Depreciation and High Costs (1947); No. 37, Accounting for Compensation in the Form of Stock Options (1948); No. 40 and No. 48, Business Combinations (1950 and 1957); No. 47, Accounting for Costs of Pension Plans (1956); and No. 51, Consolidated Financial Statements (1959).

Each ARB described one or more accounting or reporting problems that had been brought to the committee's attention and identified accepted principles (conventions, rules, methods, or procedures) to account for the item(s) or otherwise to solve the problem(s) involved, sometimes describing one or more principles as preferable. Because each Bulletin dealt with a specific practice problem or a set of related problems, the committee developed or approved accounting principles (to use the most common descriptions) case by case, ad hoc, or piecemeal.

Piecemeal Principles Based on Practice, Experience, and General Acceptance.

As a result of the way the committee operated and the bases on which it decided issues before it, the ARB became classic examples of George O. May's dictum that “the rules of accounting, even more than those of law, are the product of experience rather than of logic.”33 Despite having “research” in the name, the ARBs, rather than being the product of research or theory, were much more the product of existing practice, the collective experience of the members of the Committee on Accounting Procedure, and the need to be generally accepted.

Since the committee had not attempted to codify a comprehensive statement of accounting principles, it had no body of theory against which to evaluate the conventions, rules, and procedures that it considered. Although individual ARBs sometimes reflected one or more theories apparently suggested or applied by individual members or agreed on by the committee, as a group they reflected no broad, internally consistent, underlying theory. On the contrary, they often were criticized for being inconsistent with each other. The committee used the word “consistency” to mean that a convention, rule, or procedure, once chosen, should continue to be used in subsequent financial statements, not to mean that a conclusion in one Bulletin did not contradict or conflict with conclusions in others.

The most influential unifying factor in the ARBs as a group was the philosophy that underlay Audits of Corporate Accounts, a group of propositions that May and the Special Committee on Cooperation with Stock Exchanges had described as pragmatic and realistic—not theoretical and logical. For example, the Bulletins clearly were based on the propositions that the income statement was far more important than the balance sheet; that financial accounting was primarily a process of allocating historical costs and revenues to periods rather than of valuing assets and liabilities; that the particular rules or conventions used were less significant than consistent use of whichever ones were chosen; and that some variety in accounting conventions and rules, especially in the methods and procedures for applying them to particular situations, was inevitable and desirable.

Most of the work of the Committee on Accounting Procedure, like that of most Institute committees, was done by its members and their partners or associates, and the ARBs reflected their experience. The experience of Carman G. Blough also left its mark on the Bulletins after he became the Institute's first full-time director of research in 1944. The Institute had established a small research department with a part-time director in 1939, which did some research for the committee but primarily performed the tasks of a technical staff, such as providing background and technical memoranda as bases for the Bulletins and drafting parts of proposed Bulletins. Committee members and their associates did even more of the committee's work as the research department also began to provide staff assistance to the Committee on Auditing Procedure in 1942 and then increasingly became occupied with providing staff assistance to a growing number (44 at one time) of other technical committees of the Institute.

The accounting conventions, rules, and procedures considered by the Committee on Accounting Procedure and given its stamp of approval as principles in an ARB were already used in practice, not only because the committee had decided to look for principles in what accountants did but also because only principles that were already used were likely to qualify as “generally accepted.” General acceptance was conferred by use, not by vote of the committee. Each Bulletin, beginning with ARB 4 in December 1939, carried this note about its authority: “Except in cases in which formal adoption by the Institute membership has been asked and secured, the authority of the bulletins rests upon the general acceptability of opinions…reached.”

The committee was authorized by the Institute to issue statements on accounting principles, which the Institute expected the SEC to recognize as providing “substantial authoritative support,” but the committee had no authority to require compliance with the Bulletins. It could only add a warning to each Bulletin “that the burden of justifying departure from accepted procedures must be assumed by those who adopt other treatment.”

The committee's reliance on general acceptability of principles developed or approved case by case, ad hoc, or piecemeal invited challenges to its authority whenever it tried either to introduce new accounting practices or to proscribe existing practices. Moreover, although the SEC also dealt with accounting principles case by case, ad hoc, or piecemeal, its power to say which accounting principles had substantial authoritative support—its own version of general acceptability—limited what the committee could do without the Commission's concurrence.

Challenges to the Committee's Authority

The Committee on Accounting Procedure introduced interperiod income tax allocation in ARB No. 23, Accounting for Income Taxes (December 1944). The reason it gave for changing practice was that “income taxes are an expense that should be allocated, when necessary and practicable, to income and other accounts, as other expenses are allocated. What the income statement should reflect…is the [income tax] expense properly allocable to the income included in the income statement for the year” (page 186 [fourth page of ARB 23], carried over with some changes to ARB No. 43, Restatement and Revision of Accounting Research Bulletins (June 1953), Chapter 10B, “Income Taxes,” paragraph 4).

A committee of the New Jersey Society of Certified Public Accountants reviewed ARB 23 soon after its issue and questioned whether the new procedures it recommended were “accepted procedures” at the date of its issue. General acceptability, the committee contended, depended on the extent to which procedures were applied in practice, which only time would tell. The committee proposed that the Institute submit a new Bulletin to a formal vote a year after issue because approval of a Bulletin by more than 90 percent of its members would demonstrate its general acceptability and authority.34

The Institute ignored the proposal, but the New Jersey committee had in effect challenged the authority of the Committee on Accounting Procedure to change accounting practice, raising an issue that would not go away. The Institute's Executive Committee or its governing council found it necessary to reaffirm the committee's authority a number of times in the following years,35 and in the committee's final year its authority to change practice was challenged in court, again on a matter involving income tax allocation. Three public utilities, subsidiaries of American Electric Power, Inc., sought to enjoin the Committee on Accounting Procedure from issuing a letter dated April 15, 1959, interpreting a term in ARB No. 44 (revised), Declining-Balance Depreciation (July 1958).

The object of the letter was to express the Committee's view that the “deferred credit” used in tax-allocation entries was a liability and not part of stockholders' equity. The three plaintiff corporations alleged that classification of the account as a liability would cause them “irreparable injury, loss and damage.” They also claimed that the letter was being issued without the Committee's customary exposure, thus not allowing interested parties to comment. The Federal District Court ruled against the plaintiffs. An appeal to the Second Circuit Court of Appeals was lost, the Court saying inter alia, “We think the courts may not dictate or control the procedures by which a private organization expresses its honestly held views.” Certiorari was denied by the U.S. Supreme Court, and the committee's letter was issued shortly thereafter [July 9, 1959].36

Neither the Institute's repeated reconfirmations of the committee's status nor its success in court corrected the weaknesses inherent in accounting principles whose authority rested on their general acceptability. The Institute did not finally face up to the problem until almost two decades later when the authority of the APB was challenged on another income tax matter—accounting for the investment credit.

Influence of the Securities and Exchange Commission

Because accounting principles in the ARBs would be acceptable in SEC filings only if the Commission deemed them to have “substantial authoritative support,” two committees of the Institute carefully cultivated a working relationship with the Commission to try to ensure that the Bulletins met that condition. The Committee on Cooperation with the SEC met regularly with the SEC's accounting staff and occasionally with the Commissioners. The Committee on Accounting Procedure and the director of research met with representatives of the SEC as needed and took great pains to keep the Chief Accountant informed about the committee's work, not only sending him copies of drafts of proposed Bulletins but also seeking his comments and criticisms and, if possible, his concurrence. Efforts to secure his agreement usually were successful.37

Some differences of opinion between the Committee on Accounting Procedure and the Commission were inevitable, of course, but they were the exception rather than the rule. Most disagreements were settled amicably, as was the long-running disagreement over the current operating performance and all-inclusive or clean surplus theories of income. The committee and the Commission sometimes were able to work out a compromise solution. The committee often adopted the Commission's view, at least once withdrawing a proposed Accounting Research Bulletin because of the Commission's opposition and at other times apparently being discouraged from issuing Bulletins by the Commission. The Commission occasionally adopted the committee's view or at least delayed issue of its own accounting releases pending issue of a Bulletin by the Institute.

The Commission affected accounting practice indirectly through its influence on the ARB. It also directly exercised its power to say whether or not a set of financial statements filed with it met the statutory requirements by means of rulings and orders, some published but most private.

The Commission published some formal rules, mostly on matters of disclosure rather than accounting principles. For example, the first regulations promulgated by the newly formed SEC required income statements to disclose sales and cost of goods sold, information that many managements had long considered to be confidential. Over 600 companies, about a quarter of those required to file registration statements in mid-1935, risked delisting of their securities by refusing to disclose publicly the required information. The Commission granted hearings to a significant number of them and also heard arguments of security analysts, investment bankers, and other users of financial statements that the information was necessary. The Commission then “notified all of the companies affected that the information was necessary for a fair presentation and that this need overcame any arguments that had been advanced against it.”38

The companies had little choice but to comply, and the effect of the rule was to put reporting of sales and cost of sales in the United States decades ahead of most of the rest of the world. The controversy surrounding initial application of the rule subsided, and reporting sales and cost of goods sold has been common practice for so long that few people now know of its once controversial nature or of the Commission's part in promulgating it.

The Commission largely exercised its power behind the scenes through informal rulings and orders in “deficiency letters” on registrants' financial statements. The recipient of a deficiency letter could decide either to amend the financial statements to comply with the SEC's ruling or go to Washington to try to convince the staff, and anyone else at the Commission who would listen, of the merits of the accounting that the staff had challenged. If that informal conference process failed to produce agreement, a registrant could do little except comply or withdraw the registration and forgo issuing the securities. The only appeal to the Commission of a staff ruling on an accounting issue was in the form of a hearing to determine whether a stop order should be issued to prevent the registration from becoming effective because it contained misrepresentations—in effect “a hearing to determine whether or not [the registrant was] about to commit a fraud…. [Since b]usinessmen who have any reputation do not put themselves in the position of putative swindlers merely to determine matters of accounting,”39 those private administrative rulings effectively settled most accounting questions.

The SEC's far-reaching rule that assets must never be accounted for at more than their cost was promulgated in that way. “[N]either the Securities and Exchange Commission nor the accounting profession issued rules or guidelines directly proscribing write-ups [of assets] or supplemental disclosures of current values. The change was brought about by the intervention of the SEC's staff, who ‘discouraged’ both practices through informal administrative procedures.”40 “[T]he SEC took a stand from the very beginning…. establish[ing] its position so early [that] we often overlook the fact that in [the basis for accounting for assets] the Commission never gave the profession a chance to even consider the matter insofar as registrants are concerned.”41

In the sense that the commission's role has long been forgotten or unknown, experience with the cost rule was similar to that of the rule requiring disclosure of sales and cost of sales. But the similarity ended there. The cost rule involved accounting principle rather than disclosure. And, instead of subsiding as did resistance to the disclosure rule, controversy surrounding the cost rule intensified and in the years following the Second World War led to a major and long-lasting division within the Institute.

Because of widespread concern about the effects on financial statements of the high rate of inflation during the war and the greatly increased prices of replacing assets after the war, the Institute had created the Study Group on Business Income, financed jointly with the Rockefeller Foundation. Its report concluded that financial statements could be meaningful only if expressed in units of equal purchasing power. It advocated accounting that reflected the effects of changes in the general level of prices on the cost of assets already owned and the resulting costs and expenses from their use,42 a change in accounting considered necessary by many Institute leaders and members.

While the Study Group was still at work, the Committee on Accounting Procedure, supported by many other Institute leaders and members and by the SEC, issued ARB No. 33, Depreciation and High Costs (December 1947), which rejected “price-level depreciation” and suggested instead that management annually appropriate net income or retained earnings in contemplation of replacing productive facilities at higher price levels. The Bulletin effectively blocked use of depreciation in excess of that based on cost in measuring net income that had been contemplated or adopted by a few large companies but also provoked an active opposition to the committee's action.

Prominent among those who criticized the committee for in effect applying the SEC's cost rule instead of facing up to the accounting problems caused by the effects of changes in the general price level was George O. May,43 who had been instrumental in creating the Study Group on Business Income. He served as consultant to and then as a member of the group and later would be a joint author of its report. He criticized the committee's action for prejudging and undermining the Study Group's efforts, thereby foreclosing any real discussion of “the relation between changes in the price level and the concept of business income.”44 He considered ARB 33 to be, however, only one of a number of missteps over the following decade that showed that the committee had lost its way. He also criticized the committee, among other things, for failing to cast aside outmoded conventions in favor of others more consonant with the changed conditions in the economy and for adopting public utility accounting procedures such as the Federal Power Commission's “original (or predecessor) cost”—cost to the corporate or natural person first devoting the property to the public service rather than cost to the present owner—that the committee itself earlier had held to be contrary to generally accepted accounting principles.45

Despite the criticisms, the committee held its course, though not without some wavering. It twice considered issuing a Bulletin approving upward revaluations of assets but each time dropped the attempt in the face of the unequivocal opposition of the SEC. Although the number of dissents to the cost rule increased each time the committee revisited the question of changing price levels, the committee “was unable to marshal a two-thirds majority in favor of a new policy”46 and in 1958 dropped the subject from its agenda.

Whether it was influencing accounting practice directly through publishing rules or establishing them in informal rulings and private conferences with registrant companies or indirectly through the Committee on Accounting Procedure, the SEC generally seems to have had its way.

Decision to Issue Principles Piecemeal Reaffirmed.

The Committee on Accounting Procedure had to deal ad hoc with the SEC's comments on and objections to its Bulletins, issued or proposed, because it had no comprehensive statement of principles on which to base responses to the Commission's own ad hoc comments and rulings. Although the committee had decided early not to take the time required to develop a statement of broad principles on which to base solutions to practice problems (p. 2–12), the need for a comprehensive statement or codification of accounting principles continued to be raised occasionally, and the committee periodically revisited the question. Each time it decided against a project of that kind.

One of those occasions was in 1949, when the committee reconsidered its earlier decision and began work on a comprehensive statement of accounting principles. Ultimately, however, it again abandoned the project as not feasible and instead in 1953 issued ARB 43, Restatement and Revision of Accounting Research Bulletins. ARB 43 superseded the first 42 ARBs, except for three that were withdrawn as no longer applicable and eight that were reports of the Committee on Terminology and were reviewed and published separately in Accounting Terminology Bulletin No. 1, Review and Résumé. Although ARB 43 brought together the earlier Bulletins and grouped them by subject matter, “this collection retained the original flavor of the bulletins, i.e., a group of separate opinions on different subjects.”47

Thus, the decision of the Committee on Accounting Procedure at its first meeting to put out brush fires as they flared up rather than to codify accepted accounting principles to provide a basis for solving financial accounting and reporting problems set the course that the committee pursued for its entire 21-year history. All 51 ARBs reflected that decision.

Influence of the American Accounting Association.

During the 21 years that the Committee on Accounting Procedure was issuing the ARBs, the AAA revised its 1936 “Tentative Statement of Accounting Principles Underlying Corporate Financial Statements” in 1941, 1948, and 1957, including eight Supplementary Statements to the 1948 Revision. In the “Tentative Statement,” as already noted, the executive committee of the AAA emphasized that improvement in accounting practice could best be achieved by strengthening the theoretical framework that supported practice and attempted to formulate a comprehensive set of concepts and standards from which to derive and by which to evaluate rules and procedures. Principles were not merely descriptions of procedures but standards against which procedures might be judged.

The executive committee of the Association, like the committees of the Institute concerned with accounting principles, regarded the principles as being derived from accounting practice, although the means of derivation differed—distillation or compilation according to the Institute and theoretical analysis according to the Association. Thus, the “Tentative Statement” set forth 20 principles, each a proposition embodying “a corollary of this fundamental axiom”:

Accounting is…not essentially a process of valuation, but the allocation of historical costs and revenues to the current and succeeding fiscal periods. [p. 188]

Although the AAA's intent was to emphasize accounting's conceptual underpinnings, the “Tentative Statement” was substantially less conceptual and more practice oriented than might appear, not only because its principles were derived from practice but also because its “fundamental axiom” was essentially a description of existing practice. The same description of accounting was inherent in the report of the Special Committee on Cooperation with Stock Exchanges, was voiced by George O. May at the annual meeting of the Institute in October 193548 and was evident in most of the ARBs.

That the principles in the Statements of the AAA were significantly like those in the ARBs should come as no surprise. “Inasmuch as both the Institute and the Association subscribed to the same basic philosophy regarding the nature of income determination, it was more or less inevitable that they should reach similar conclusions, even though they followed different paths.”49

The AAA's 1941 and 1948 revisions generally continued in the direction set by the 1936 “Tentative Statement.” Some changes began to appear in some of the Supplementary Statements to the 1948 Revision and in the 1957 Revision. They probably were too late, however, to have had much effect on the ARBs, even if the Committee on Accounting Procedure had paid much attention.

Long-lasting influence on accounting practice of the “Tentative Statement,” as noted earlier, came some time after it was issued and mostly indirectly through two of its principles on “all-inclusive income” (one a corollary of the other) and a monograph by W. A. Paton and A. C. Littleton.

“All-Inclusive Income” versus “Avoiding Distortion of Periodic Income.”

“A Tentative Statement of Accounting Principles Underlying Corporate Financial Statements” strongly supported what was later called the all-inclusive income or clean surplus theory. The principle (No. 8, p. 189), which gave the theory one of its names, was that an income statement for a period should include all revenues, expenses, gains, and losses properly recognized during the period “regardless of whether or not they are the results of operations in that period.” The corollary (No. 18, p. 191), which gave the theory its other name, was that no revenues, expenses, gains, or losses should be recognized directly in earned surplus (retained earnings or undistributed profits).

The SEC later strongly supported that accounting, and it became a bone of contention between the SEC and the Committee on Accounting Procedure. The committee generally favored the “current operating performance” theory of income, which excluded from net income extraordinary and nonrecurring gains and losses “to avoid distorting the net income for the period.” The disagreement broke into the open with the issue of ARB No. 32, Income and Earned Surplus [Retained Earnings] (December 1947), whose publication in the January 1948 issue of The Journal of Accountancy was accompanied by a letter from SEC Chief Accountant Earle C. King saying that the “Commission has authorized the staff to take exception to financial statements which appear to be misleading, even though they reflect the application of Accounting Research Bulletin No. 32 (p. 25).” Two more Bulletins, ARB No. 35, Presentation of Income and Earned Surplus (October 1948), and ARB No. 41, Presentation of Income and Earned Surplus (Supplement to Bulletin No. 35) (July 1951), followed as the committee and the SEC tried to work out a number of compromises. Each effort proved unsatisfactory to one or both parties.

Years later the APB would adopt an all-inclusive income statement in APB Opinion No. 9, Reporting the Results of Operations (December 1966). That accounting and reporting has since been modified by admitting some significant exceptions, primarily by FASB Statement No. 12, Accounting for Certain Marketable Securities (December 1975),50 and FASB Statement No. 52, Foreign Currency Translation (December 1981). Thus, net income reported under current generally accepted accounting principles cannot accurately be described as all-inclusive income, but the idea of all-inclusive income is still generally highly regarded, and many still see it as a desirable goal to which to return.

“Matching of Costs and Revenues” and “Assets Are Costs.”

Two members of the AAA executive committee that issued “A Tentative Statement of Accounting Principles Underlying Corporate Financial Statements” in 1936 undertook to write a monograph to explain its concepts. The result, An Introduction to Corporate Accounting Standards, by W. A. Paton and A. C. Littleton (1940), easily qualifies as the academic writing that has been most influential in accounting practice. Although the monograph rejected certain existing practices—such as last in, first out (LIFO) and cost or market, whichever is lower—it generally rationalized existing practice, providing it with what many saw as a theoretical basis that previously had been lacking.

The monograph accepted two of the premises that underlay the ARBs: (1) that periodic income determination was the central function of financial accounting—“the business enterprise is viewed as an organization designed to produce income”51—and (2) that (in the words of the “fundamental axiom” of the AAA's 1936 “Tentative Statement”) accounting was “not essentially a process of valuation, but the allocation of historical costs and revenues to the current and succeeding fiscal periods.”

The fundamental problem of accounting, therefore, is the division of the stream of costs incurred between the present and the future in the process of measuring periodic income. The technical instruments used in reporting this division are the income statement and the balance sheet…. The income statement reports the assignment [of costs] to the current period; the balance sheet exhibits the costs incurred which are reasonably applicable to the years to come.52

The monograph described the periodic income determination process as the “matching of costs and revenues,” giving it not only a catchy name but also strong intuitive appeal—a process of relating the enterprise's efforts and accomplishments. The corollary was that most assets were “deferred charges to revenue,” costs waiting to be “matched” against future revenues:

The factors acquired for production which have not yet reached the point in the business process where they may be appropriately treated as “cost of sales” or “expense” are called “assets,” and are presented as such in the balance sheet. It should not be overlooked, however, that these “assets” are in fact “revenue charges in suspense” awaiting some future matching with revenue as costs or expenses.

The common tendency to draw a distinction between cost and expense is not a happy one, since expenses are also costs in a very important sense, just as assets are costs. “Costs” are the fundamental data of accounting….

The balance sheet thus serves as a means of carrying forward unamortized acquisition prices, the not-yet-deducted costs; it stands as a connecting link joining successive income statements into a composite picture of the income stream.53

Not surprisingly, those who had supported the accounting principles developed in the ARBs but were uncomfortable with those principles' apparent lack of theoretical support found highly attractive the theory that “matching costs and revenues” not only determined periodic net income but also justified the practice of accounting for most assets at their historical costs or an unamortized portion thereof.

However, just as the institutionalizing of a broad definition of accounting principles had caused problems for the Committee on Accounting Procedure itself and later for the APB, the institutionalizing of “matching costs with revenues,” “costs are assets,” and “avoiding distortion of periodic income” also caused problems for the FASB in developing a conceptual framework for financial accounting and reporting. The FASB found those expressions not only to be ingrained in accountants' vocabularies and widely used as reasons for or against particular accounting or reporting procedures but also to be generally vague, highly subjective, and emotion laden. They have proven to be of minimal help in actually resolving difficult accounting issues.

(iii) Failure to Reduce the Number of Alternative Accounting Methods

The Institute's effort aimed at improving accounting by reducing the number of acceptable alternatives probably did improve accounting by culling out some “bad” practices.

There are those who seem to believe that very little progress has been made towards the development of accounting principles and the narrowing of areas of differences in the principles followed in practice.

It is difficult for me to see how anyone who has knowledge of accounting as it was practiced during the first quarter of this century and how it is practiced today can fail to recognize the tremendous advances that have taken place in the art.54

A number of the practices for whose acceptance Sanders, Hatfield, and Moore's Statement of Accounting Principles had been lambasted55 had disappeared by about 1950. It is uncertain, however, how much of that improvement was due to the ARBs and how much to other factors, such as the good professional judgment of corporate officials or auditors or the SEC's rejection of some egregious procedures.

Ironically, the end result was an overabundance of “good” practices that had survived the process. That plethora of sanctioned alternatives for accounting for similar transactions continued to thrive despite the committee's charge to reduce the number of alternative procedures because, just as Will Rogers never met a man he didn't like, the committee rarely met an accounting principle it didn't find acceptable.

Two factors contributed to the increase in the number of accepted alternatives: (1) the committee on accounting procedure failed to make firm choices among alternative procedures, and (2) the committee was clearly reluctant to condemn widely used methods even though they were in conflict with its recommendations. For example, in its very first pronouncement on a specific problem—unamortized discount and redemption premium on refunded bonds [ARB 2]—the committee considered three possible procedures, of which it rejected one and accepted two.

The committee had a clear preference—it praised the method of amortization of cost over the remaining life of the old bonds as consistent with good accounting thinking regarding the relative importance of the income statement and the balance sheet. It condemned immediate writeoff as a holdover of balance-sheet conservatism which was of “dubious value if attained at the expense of a lack of conservatism in the income account, which is far more significant” [ARB 2, p. 13]. Nevertheless, the latter method had “too much support in accounting theory and practice and in the decisions of courts and commissions for the committee to recommend that it should be regarded as unacceptable or inferior.” [ARB 2, p. 20]