Chapter 20

Partnerships and Joint Ventures

The editors wish to acknowledge the previous contribution to this chapter by George N. Dietz, CPA, American Institute of Certified Public Accountants; Gerard L. Yarnall, CPA, Deloitte & Touche; and Ronald J. Patten, PhD, CPA, DePaul University.

20.1 Nature and Organization of The Partnership Entity

(b) Advantages and Disadvantages of a Partnership

(d) Importance of the Partnership

(e) Formation of a Partnership

20.2 Accounting for Partnership Operations

(a) Peculiarities of Partnership Accounting

(b) Methods of Dividing Profits and Losses

(c) Example Using Average Capital Ratio

(d) Treatment of Transactions Between Partner and Firm

(i) Interest on Invested Capital

(iv) Debtor–Creditor Relationship

(v) Landlord–Tenant Relationship

(e) Closing Operating Accounts

(i) Division of Profits Illustrated

(ii) Statement of Partners' Capitals Illustrated

20.3 Accounting for Changes in Firm Membership

(a) Effect of Change in Partners

(b) New Partner Purchasing an Interest

(ii) Purchase at More than Book Value

(iii) Purchase at Less than Book Value

(c) New Partner's Investment to Acquire an Interest

(ii) Investment at More than Book Value

(iii) Investment at Less Than Book Value

(d) Settling with Withdrawing Partner Through Outside Funds

(ii) Sale at More Than Book Value

(iii) Sale at Less Than Book Value

(e) Settlement Through Firm Funds

(i) Premium Paid to Retiring Partner

(ii) Discount Given by Retiring Partner

(f) Adjustment of Capital Ratios

20.4 Incorporation of a Partnership

20.5 Partnership Realization and Liquidation

(b) Liquidation by Single Cash Distribution

(c) Liquidation by Installments

(d) Capital Credits Only—No Capital Deficiency

(i) Capital Credits Only—Capital Deficiency of One Partner

(ii) Installment Distribution Plan

(b) Differences Between Limited Partnerships and General Partnerships

(c) Formation of Limited Partnerships

(d) Accounting and Financial Considerations

(i) Financial Statement Reporting Issues

(ii) Financial Statement Disclosure Issues

20.7 Nonpublic Investment Partnerships

(b) Accounting by Joint Ventures

(c) Accounting for Investments in Joint Ventures

20.9 Sources and Suggested References

20.1 Nature and Organization of The Partnership Entity

(a) Definition of Partnership

The Uniform Partnership Act (UPA), which has been adopted by most of the U.S. states, defines a partnership as an association of two or more persons who contribute money, property, or services to carry on as co-owners a business for profit.

A partnership may be general or limited. In the general partnership, each partner may be held personally responsible for all the firm's debts, whereas in the limited partnership, the liability of certain partners is limited to their respective contributions to the capital of the firm. The limited partnership is composed of a general partner and limited partners with the latter playing no role in the management of the business. Limited partnerships are discussed in Section 20.6.

While partnerships remain popular as a form of business organization, they are not as common as they once were. The Tax Reform Act of 1986 has served to dampen the attractiveness of limited partnerships as tax shelters. Similarly, new accounting standards that require consolidation of investees have made the use of partnerships and joint venture for purposes such as research and development less advantageous. At the same time, many law firms and public accounting firms that were organized as general partnerships are tending to organize themselves as professional corporations as a result of the favorable tax status that can flow from that structure as well as the easing of state laws forbidding professional firms to incorporate.

(b) Advantages and Disadvantages of a Partnership

Jules I. Bogen states:

The partnership form of organization is superior to the proprietorship because it permits several persons to combine their resources and abilities to conduct a business. It is easier to form than a corporation, and retains a personal character making it more suitable in professional fields.1

A distinct advantage of a partnership over a corporation is the close relationship between ownership and management. This provides more flexible administration as well as more management talent with a personal interest in the problems and success of the business.

Historically, the three outstanding disadvantages of the partnership form of organization, as compared with corporate form, were recognized as (1) unlimited liability of the partners for business debts, (2) mutual agency power of each partner as it pertains to business actions, and (3) limited life of the partnerships. However, the existence of a number of large partnerships, particularly in the fields of law, accountancy, and investment banking, indicates that to a great degree many of these disadvantages may be more apparent than real. In addition, partnerships have devised a number of ways to overcome some of the drawbacks. For example, since the partnership is subject to dissolution upon the death, bankruptcy, insanity, or retirement of a partner—events that do not affect the continuity of a corporation—long-term commitments for the business unit are difficult to obtain. Many partnership agreements overcome this drawback by providing for automatic continuation by the remaining partners subject to liquidation of the former partner's interest. In a sense, these partnerships have an unlimited life.

Still, the unlimited liability condition, which creates the possibility of loss of personal assets on the part of each partner, is a retardant to many. This risk of loss is especially important when one considers that each party is assumed to be an agent for all partnership activities, with the power to bind other partners as a result of his or her actions. Again, however, some partnerships have managed to overcome these difficulties, at least partially, by adopting variations of the partnership form of organizations. Such variants include:

- Limited liability companies. Limited liability companies (LLCs) are a relatively new form of business entity in the United States and have characteristics of both corporations and partnerships. LLCs shield their owners (or members) from personal liability for certain of the entity's debts and obligations, in much the same manner as a corporation. At the same time, a properly organized LLC can be treated as a partnership for federal income tax purposes, enabling it to enjoy the tax item pass-through and other benefits of the standard partnership form.

- Registered limited liability partnerships. Registered limited liability partnerships (LLPs), a distant relative of the LLC, are a type of general partnership that protects the partners' personal assets if another of their partners is sued for malpractice. However, the assets of the partnership itself remain at risk, as do the personal assets of the accused partner, and all partners still retain the standard joint-and-several liabilities of the partnership (e.g., lease obligations and bank loans).

- Limited partnerships. The limited partnership form has proliferated in recent years as a vehicle for raising capital for a particular project or undertaking. Limited partnerships are particularly common in the leasing and oil and gas industries. Prior to the Tax Reform Act of 1986, the limited partnership form also served as the organizational structure for a number of tax shelters. Limited partners risk losing their limited liability the more they participate in the management or control of the partnership's activities, thus reducing the attractiveness of the limited partnership structure for some potential partners. See Section 20.6 for further discussion of limited partnerships.

- Joint ventures. The formation and operation of joint ventures often includes partnerships. In a typical corporate joint venture, two or more entities form a partnership to undertake a specific business project, often for a specific, agreed-upon period. Each party's contributions to the venture may vary widely from case to case. For example, one corporation may provide technology, personnel, or facilities while the other contributes only the cash or other operating capital required for the undertaking. Alternatively, the venturers may jointly provide some or all of these elements. In any event, the entities form an enterprise that will function as a partnership, even if that partnership has the legal status of a corporation. See Section 20.8 for further discussion of joint ventures.

(c) Tax Considerations

Even though a partnership is not considered a separate taxable entity for purposes of paying and determining federal income taxes, it is treated as such for purposes of making various elections and for selecting its accounting methods, taxable year, and method of depreciation.

Under Section 761(a) of Subchapter K of the Internal Revenue Code (IRC) of 1954, certain unincorporated organizations may be excluded, completely or partially, from treatment as partnerships for federal income tax purposes. This exclusion applies only to those organizations used (1) for investment purposes rather than as the active conduct of a business, or (2) for the joint extraction, production, or use of property, but not for the purpose of selling the products or services extracted or produced.

The use of limited partnerships because of favorable tax considerations has been significantly reduced as a result of the Tax Reform Act of 1986. Prior to passage of that Act, limited partnerships as a form of tax-sheltered investment had been used in real estate, motion picture production, oil drilling, cable television, cattle feeding, and research and development. The limited partnership gave investors the tax advantages of the partnership such as the pass-through of losses while at the same time limiting their liability to the original investment. The Tax Reform Act of 1986 changed the situation considerably, however.

IRC Section 465 generally limits a partner's loss to the amount that the partner has “at risk” and could actually lose from an activity. These rules, which apply to individuals and certain closely held corporations, are designed to prevent taxpayers from offsetting trade, business, or professional income with losses from investments in activities that are, for the most part, financed by nonrecourse loans for which they are not personally liable. If it is determined that the loss is deductible under these “at-risk” rules, the taxpayer is subjected to “passive activity” loss rules. Generally, losses from passive trade or business activities, such as in a partnership where the partner is not active, may not be deducted from other types of income such as wages, interest, or dividends according to IRC Section 469.

Some substantial tax benefits can still be enjoyed by investing in a triple net lease limited partnership. These partnerships buy buildings that are used by fast-food, auto parts, and other chains and franchises that do not want mortgage debt on their balance sheet. The partnerships collect rent and pass it along to the partners net of three costs—insurance, upkeep, and property taxes—paid by the tenants.

(d) Importance of the Partnership

In the United States, the single proprietorship is the most common form of business organization in terms of number of establishments, and the corporate form does by far the greatest volume of business. Nevertheless, the partnership form of organization holds an important place in both respects and fills a significant need. It is widely employed among the smaller business units and in professional fields such as medicine, law, dentistry, and accountancy, activities in which the partners are closely identified with the operation of the business or profession. Partnerships are also found in financial lines, such as investment banks. Occasionally a substantial trading or other business is conducted as a partnership.

(e) Formation of a Partnership

The agreement among the copartners that brings the partnership into existence may be oral or written. The latter is much to be preferred. According to Bedford, Perry, and Wyatt:

Since a partnership is based on a contract between two or more persons, it is important, although not necessarily a legal requirement, that special attention be given to the drawing up of the partnership agreement. This agreement is generally referred to as the “Articles of Copartnership.” In order to avoid unnecessary and perhaps costly litigation at some later date, the Articles should contain all of the terms of the agreement relating to the formation, operation, and dissolution of the partnership.2

Each partner should sign the articles and retain a copy of the agreement. It is desirable that a copy of the agreement be filed with the recorder, clerk, or other official designated to receive such documents in the county in which the partnership has its principal place of business. In the case of a limited partnership, such filing is imperative. There may also be a requirement that the agreement be published in newspapers.

According to Bogen, the articles of copartnership should cover these 12 matters:

In the event that contributions of assets other than cash are being made to the new firm, the articles should also cover the matter of income tax treatment upon the subsequent disposal of such assets. In general, such assets retain the tax basis of the previous owner so that the taxable gain or loss when ultimately disposed of may be greater or less than the gain or loss to the partnership.

Many partnerships have been plagued, if not entirely destroyed, by disagreements that could have been avoided, or greatly minimized, by the exercising of more care and skill in the drafting of the original agreement.

(f) Initial Balance Sheet

Section 8 of the UPA states that:

- All property originally brought into the partnership or subsequently acquired, by purchase or otherwise, on account of the partnership is partnership property.

- Unless the contrary intention appears, property acquired with partnership funds is partnership property.

It follows that the initial balance sheet should explicitly identify the assets contributed by partners as belonging to the partnership and assign values to these assets that are agreeable to all partners. Debts assumed by the partnership will receive comparable treatment. The initial balance sheet should also show the total initial proprietorship and the partners' shares therein. According to Moonitz and Jordan:

The most direct manner of accomplishing this result is to include the initial balance sheet in the partnership agreement itself. If it is not expedient to include it as an integral part of the agreement, reference to the initial balance sheet should be made in the agreement, and the balance sheet, as a separate document, should be signed by each partner.4

Unambiguous identification of assets and obligations at the inception of the partnership is important for at least two reasons:

20.2 Accounting for Partnership Operations

(a) Peculiarities of Partnership Accounting

In many respects, the accounting problems of the partnership are the same as those of other forms of business organization. The underlying pattern of the accounting for the various assets and current goods and service costs, including departmental classification and assignment, is not modified by the type of ownership and method of raising capital employed. The same is true of the recording of revenues and the treatment of liabilities. The special features of partnership accounting relate primarily to the recording and tracing of capital, the treatment of personal services furnished by the partners, the division of profits, and the adjustments of equities required upon the occasion of reorganization or liquidation of the firm.

(b) Methods of Dividing Profits and Losses

As stated in Section 18 of the UPA, partnership income is shared equally unless otherwise provided for in the partnership agreement. In some cases, the agreement may specify division of profits in an arbitrary ratio (which of course includes the equal ratio already mentioned), referred to elsewhere in this discussion as the income ratio. Such a specified ratio (e.g., 60–40, 2/3 – 1/3) may or may not be related to the original capital contributions of the respective partners. It is reiterated that the essential point is agreement among the partners as to how they wish profits to be divided.

Another example of profit division by a single set of relationships is afforded by division in proportion to capital balances. Since this phrase is ambiguous, the agreement should specify which of these bases are intended:

(c) Example Using Average Capital Ratio

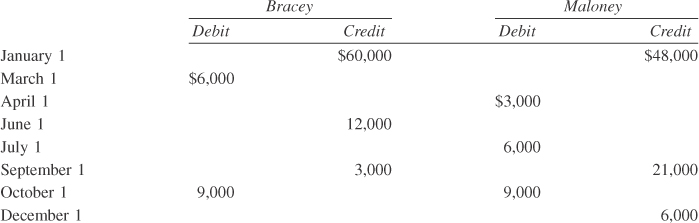

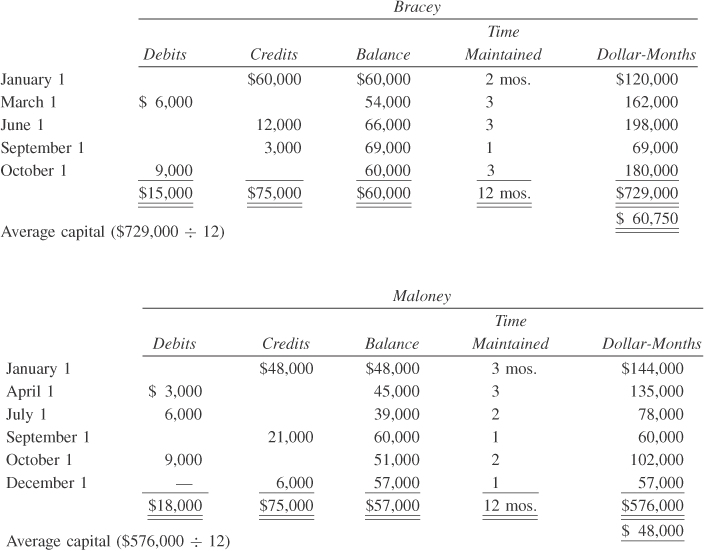

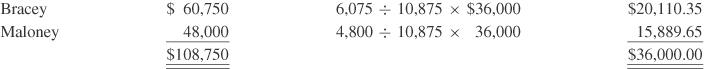

The next example shows the division of profits and losses on the basis of average capital ratios.

The Articles of Co-partnership of Bracey and Maloney provide for the division of profits on the basis of the average capital balances as shown for the year by the books of the partnership. Effect is to be given to all contributions and withdrawals during the year. The capital accounts for the year appear as follows:

Computation of average capital is as follows:

If net profit for the year is $36,000, it is distributed as follows:

This method assumes each month to be of equal significance. If the contributions and withdrawals are dated irregularly, it might be desirable to use days rather than months as the time unit.

(d) Treatment of Transactions Between Partner and Firm

It has often been pointed out that no single profit-sharing ratio can yield equitable results under all circumstances in view of the various contributions of the partners to the firm activities. Accordingly, the articles may well include provisions regarding allowances for (1) interest on invested capital, (2) salaries for services rendered, and (3) bonuses. The ratio for dividing the profit or loss remaining after applying such provisions must, of course, also be specified.

(i) Interest on Invested Capital

The partnership agreement should cover at least four points in the matter of allowing interest on invested capital:

The rate of interest may be stated specifically or it may be determined by reference to the call money market, the yield of certain governmental obligations, the charge made by local banks for commercial loans, or some other available measure.

If the articles provide for a regular interest allowance, there should be included a statement of how to deal with the cases in which the firm operates at a loss or has a net profit of less than the interest. Two ways of dealing with these contingencies are: (1) the interest allowance may be dropped or reduced (when there is some profit) for the period in question; (2) the full interest may be allowed and the resulting net debit in the income account apportioned in the income (profit-sharing) ratio. The second procedure is customary for cases in which the articles do not cover the point precisely.

(ii) Partners' Salaries

Each working partner should be entitled to a stated salary as compensation for his or her services, just as each investing partner should receive interest on his or her capital investment. (The general rule, from a legal standpoint, is that a partner is not entitled to compensation for services in carrying on the business, other than his or her share in the profits, unless such compensation is specifically authorized in the partnership agreement.) It is always desirable that the articles of partnership specify the amounts of salaries or wages to be paid to partners or indicate clearly how the amounts are to be determined. The agreement regarding salaries should also cover the contingencies of inadequate income and net losses in particular periods.

Charges for salaries designed to represent reasonable allowances for personal services rendered by the partners are often viewed as operating expenses, and this interpretation may be included in the agreement. Under this interpretation, there would seem to be good reason for concluding that regular salaries should be allowed, whether or not the business is operated at a profit. As is the case with interest allowances on capital investments, there is strong presumption that if salaries are authorized in the agreement, they must be allowed, regardless of the level of earnings, in all cases in which a contrary treatment is not prescribed.

Treatment of salary allowances as business expenses is convenient from the standpoint of accounting procedure, particularly in that this treatment facilitates appropriate departmentalization of such charges. However, it must not be forgotten that partners' salaries, like interest allowances, are essentially devices intended to provide equitable treatment of partners who are supplying unlike amounts of capital and services to the firm; the purpose, in other words, is to secure an equitable apportionment of earnings.

According to Bedford, a distinct rule, “derived from custom and from law,” that applies in accounting for partnership owners' equities is that “the income of a partnership is the income before deducting partners' salaries; partners' salaries are treated as a means of dividing partnership income.”5

Dixon, Hepworth, and Paton, however, indicate that the interpretation of partners' salaries should vary with the circumstances:

Where there are a substantial number of partners, and salaries are allowed to only one or two members who are active in administration, there is practical justification for treating such salaries as operating charges closely akin to the cost of services furnished by outsiders. This is especially defensible where the salaries are subject to negotiation from period to period and are in no way dependent upon the presence of net earnings. Where there are only two partners, and both capital investments and contributions of services are substantially equal, there is less need for salary adjustments; if “salaries” are allowed in such a situation it would seem to be reasonable to interpret them as preliminary distributions of net income—an income derived from a coordination of capital and personal efforts in a business venture. Between these two extremes there lies a range of less clear-cut cases.6

(iii) Bonuses

Where a particular partner furnishes especially important services, the device of a bonus—usually expressed as a percentage of net income—may be employed as a means of providing additional compensation. The principal question that arises in such cases is the interpretation of the bonus in relation to the final net amount to be distributed according to the regular income ratio, as illustrated in the next example.

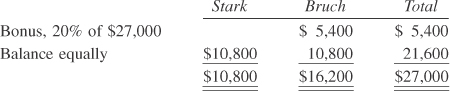

Stark and Bruch share profits equally. Per the partnership agreement, Bruch is to receive a bonus of 20 percent of the net income of the firm, before allowing the bonus, for special services to the firm. If in a particular year the credit balance of the expense and revenue account is $27,000 before allowing the bonus, profits are divided as follows:

If the bonus is to be treated as an expense item in the computation of the final net income, the $27,000 credit balance of the expense and revenue account represents both the bonus and the final net income. Hence the $27,000 is 120 percent of the net income, and the net income is 100 percent, or $22,500. Under this method, the profits are divided as follows:

(iv) Debtor–Creditor Relationship

At times, when a partnership is formed, a partner may not be interested in investing more than a certain amount of assets on a permanent basis. That partner, therefore, may make an advance to the partnership that is viewed as a loan rather than an increase in his or her capital account. The firm may thus obtain the initial financing it needs without having to negotiate with an outside source on less favorable terms. The loan may be interest bearing and may be repayable in installments. Interest charges on such loans should be treated as an expense of the partnership, and the loan itself should be disclosed clearly as a liability of the firm.

Occasionally, a partner may withdraw a sum from the partnership. This type of transaction should be treated in the manner dictated by the circumstances. If the loan is material relative to the partner's net personal assets, if no repayment terms are stipulated, and if the loan has been long outstanding, the loan is, in effect, a withdrawal and should be viewed as a contraction of the firm's capital. If, however, the partner has every intention of repaying the sum, the loan may be regarded as a valid receivable.

(v) Landlord–Tenant Relationship

In some cases, a partner may rent property from or to the partnership. Transactions of this type should be handled exactly as rental agreements with others are handled. The only possible difference in recording this type of event would find the rent receivable from a partner being debited to his or her drawing or capital account instead of to a “rent receivable” account. If the rent was owed to the partner, the payable could be recorded as a credit to either the partner's drawing or capital account. To minimize the possibility of confusion, it is preferable to record rental transactions with partners in the same manner as other rental agreements.

(vi) Statement Presentation

Receivables and payables arising out of transactions between a partner and the firm of which he or she is a partner should be classified in the balance sheet in the same manner as are receivables and payables arising out of transactions with nonpartners. However, any such receivables and payables included in the balance sheet should be set forth separately; they should not be combined with other receivables and payables. Accounting Standards Codification (ASC) Statement of Financial Accounting Standards (SFAS) No. 57 indicates that receivables or payables involving partners stem from a related party transaction and, as such, if material, should be disclosed in such a way as to include these four items:

(e) Closing Operating Accounts

The operating accounts are closed to the expense and revenue account in the usual manner. That account is then closed by crediting each partner's capital account with his or her share of the net income or debiting it with his or her share of the net loss. The drawing account of each partner is then closed to the respective capital account.

(i) Division of Profits Illustrated

The articles of co-partnership of the fictitious firm of Ahern and Ciecka include these provisions as to distribution of profits:

Partners' loans. Loans made by partners to the firm shall draw interest at the rate of 6% per annum. Such interest shall be computed only on December 31 of each year regardless of the period in which the loan was in effect.

Partners' salaries. On December 31 of each year, salaries shall be allowed by a charge to the expense and revenue account and credits to the respective drawing accounts of the partners at the following amounts per annum: Ahern $14,400; Ciecka, $12,000. Partners' salaries are to be allowed whether or not earned.

Interest on partners' invested capital. Each partner is to receive interest at the rate of 6% per annum on the balance of his capital account at the beginning of the year. Such interest is to be allowed whether or not earned.

Remainder of profit or loss. The balance of net income after provision for salaries, interest on loans, and interest on invested capital is to be divided equally. Any loss resulting after provision for the above items is to be divided equally.

On December 31, the books of the partnership show these balances before recognition of interest and salary adjustments:

| Sundry assets | $309,000 | |

| Sundry liabilities | $66,000 | |

| Ahern, capital | 120,000 | |

| Ahern, drawings | 15,000 | |

| Ciecka, capital | 60,000 | |

| Ciecka, drawings | 9,000 | |

| Ciecka, loan | 30,000 | |

| Expense and revenue | – | 57,000 |

| $333,000 | $333,000 |

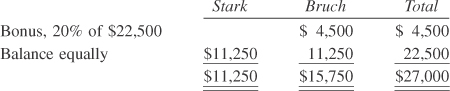

Balances of the capital accounts on January 1 were: Ahern $105,000; Ciecka $48,000. The loan from Ciecka was made on April 1. Division of profits is as shown in Exhibit 20.1.

Exhibit 20.1 Division of Profits

(ii) Statement of Partners' Capitals Illustrated

Formal presentation of the activity of the partners' capital accounts is often made through the statement of partners' capitals (Exhibit 20.2).

Exhibit 20.2 Sample Statement of Partners' Capitals

(f) Income Taxes

According to William H. Hoffman, Jr.:

Unlike corporations, estates, and trusts, partnerships are not considered separate taxable entities. Instead, each member of a partnership is subject to income tax on their distributive share of the partnership's income, even if an actual distribution is not made. (Section 701 of Subchapter K of the 1954 Code contains the statutory rule that the partners are liable for income tax in their separate or individual capacities. The partnership itself cannot be subject to the income tax on its earnings.) Thus, the tax return (Form 1065) required of a partnership serves only to provide information necessary in determining the character and amount of each partner's distributive share of the partnership's income and expense.7

Some states, however, impose an unincorporated business tax on a partnership that for all practical purposes is an income tax.

20.3 Accounting for Changes in Firm Membership

(a) Effect of Change in Partners

From a legal point of view, the withdrawal of one or more partners or the admission of one or more new members has the effect of dissolving the original partnership and bringing into being a new firm. This means that the terms of the original agreement as such are not binding on the successor partnership. As far as the continuity of the business enterprise is concerned, however, a change in firm membership may be of only nominal importance; with respect to character of the business, operating policies, relations with customers, and so on, there may be no substantial difference between the new firm and its predecessor.

To determine the value of the equity of a retiring partner or the amount to be paid for a specified share by an incoming partner, a complete inventory and valuation of firm resources may be required. Estimation of interim profits and unrealized profits on long-term contracts may be involved. In any event, there should be a careful adjustment of partners' equities in accordance with the new relationships established.

A withdrawing partner may continue to be liable for the firm's obligation incurred prior to his or her withdrawal unless the settlement includes specific release therefrom by the continuing partners and by the creditors.

A person admitted as a partner into an existing partnership is liable for all the obligations of the partnership arising before his or her admission as if he or she had been a partner when such obligations were incurred, except that this liability shall be satisfied only out of partnership property.

(b) New Partner Purchasing an Interest

It is possible for a party to acquire the interest of a partner without becoming a partner. A member of a partnership may sell or assign his or her interest, but unless this has received the unanimous approval of the other partners, the purchaser does not become a partner; one partner cannot force copartners into partnership with an outsider. Under the UPA, the buyer in such a case acquires only the seller's interest in the profits and losses of the firm and, upon dissolution, the interest to which the original partner would have been entitled. The buyer has no voice in management, nor may he or she obtain an accounting except in case of dissolution of the business; ordinarily the buyer can make no withdrawal of capital without the consent of the partners.

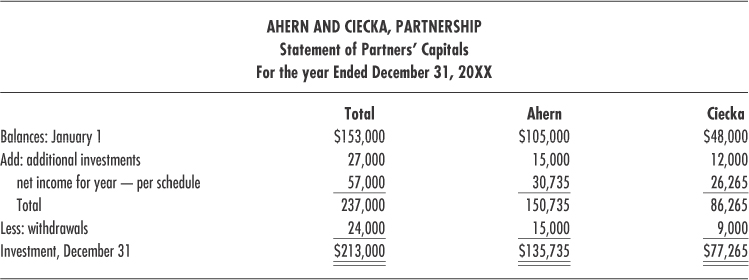

To illustrate some of the possibilities in connection with purchase of an interest, assume that the firm of Hirt, Thompson, and Pitts negotiates with Davis for the purchase of a capital interest. Data are as follows:

| Capital Accounts | Income Ratio | |

| Hirt | $20,000 | 50% |

| Thompson | 12,000 | 40 |

| Pitts | 8,000 | 10 |

| $40,000 | 100% |

(i) Purchase at Book Value

If Davis purchases a one-fourth interest for $10,000, it is clear that she is paying exactly book value, and the entry would be:

| Hirt, capital | $5,000 | |

| Thompson, capital | 3,000 | |

| Pitts, capital | 2,000 | |

| Davis, capital | $10,000 |

The cash payment would be divided in the same manner (i.e., Hirt $5,000, Thompson $3,000, and Pitts $2,000) and would pass directly from Davis to them without going through the firm's cash account.

(ii) Purchase at More than Book Value

Assume now that Davis agrees to pay $12,000 for a one-fourth interest; this is more than book value. In general, two solutions are possible.

Bonus Method.

Under this method, the extra $2,000 paid by Davis is considered to be a bonus to Hirt, Thompson, and Pitts and is shared by them in the income ratio. The entry is:

| Hirt, capital | $5,000 | |

| Thompson, capital | 3,000 | |

| Pitts, capital | 2,000 | |

| Davis, capital | $10,000 |

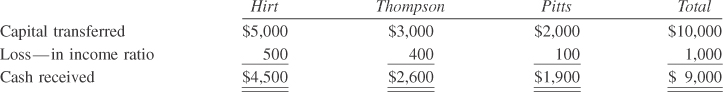

The cash payment of $12,000 is divided as shown:

Goodwill Method.

That Davis is willing to pay $12,000 for a one-fourth interest indicates that the business is worth $48,000. Existing assets are therefore undervalued by $8,000. Under the goodwill or revaluation of assets method, if specific assets can be revalued, this should be done. If not, or if the agreed revaluation is less than $8,000, the difference may be assumed to be goodwill. Dividing the gain in the income ratio results in this entry:

| Sundry, assets and/or goodwill | $8,000 | |

| Hirt, capital | $4,000 | |

| Thompson, capital | 3,200 | |

| Pitts, capital | 4,800 |

The entry to record Davis's admission would then be:

| Hirt, capital | $6,000 | |

| Thompson, capital | $3,800 | |

| Pitts, capital | 2,200 | |

| Davis, capital | 12,000 |

The cash payment will be received in amounts equal to the transfer from the capital accounts.

(iii) Purchase at Less than Book Value

Assume next that Davis agrees to pay only $9,000 for a one-fourth interest—that is, less than book value. Again two solutions are possible.

Bonus Method.

Under this method, the same transfers are made from the three partners to Davis's capital account as if she had paid book value, but the difference of $1,000 is apportioned to determine the cash settlement, as follows:

Revaluation of Assets Method.

This approach reasons that a price of $9,000 for a one-fourth interest indicates that the business is worth $36,000 and that assets should be revalued downward by $4,000. Where a portion of the write-down can be identified with specific tangible assets, the appropriate accounts should be adjusted. Otherwise, existing goodwill should be included in the write-down. The entries would be:

| (1) | ||

| Hirt, capital | $2,000 | |

| Thompson, capital | 1,600 | |

| Pitts, capital | 2,400 | |

| Sundry, assets and/or goodwill | $4,000 | |

| (2) | ||

| Hirt, capital | $4,500 | |

| Thompson, capital | 2,600 | |

| Pitts, capital | 1,900 | |

| Davis, capital | $9,000 |

(c) New Partner's Investment to Acquire an Interest

The admission of a new partner when he or she makes an investment in the firm to acquire a capital interest is illustrated by the following cases.

Assume that the capital account balances of the partnership of Andrews and Bell prior to the admission of Cohen are:

| Capital Accounts | Income Ratio | |

| Andrews | $18,000 | 60% |

| Bell | 12,000 | 40 |

| $30,000 | 100% |

(i) Investment at Book Value

If Cohen invests $10,000 in the firm for a one-fourth interest, the entry is:

| Cash (or other assets) | $10,000 | |

| Cohen, capital | $10,000 |

(ii) Investment at More than Book Value

If Cohen is willing to invest $14,000 for a one-fourth interest, the total capital will be $44,000.

Bonus Method.

Under this method, Cohen's share is one-fourth or $11,000, and the $3,000 premium is treated as a bonus to the old partners by the entry:

| Cash (or other assets) | $14,000 | |

| Andrews, capital | $1,800 | |

| Bell, capital | 1,200 | |

| Cohen, capital | 11,000 |

Goodwill Method.

If Cohen invests $14,000 for a one-fourth interest, it would seem that the total worth of the firm should be $56,000. Since total capital is $44,000, under the goodwill or revaluation of assets method, there is justification in assuming that existing assets are undervalued to the extent of $12,000. Circumstances may indicate that the $12,000 undervaluation is in the form of goodwill. If it is to be recognized, the entries are:

| (1) | ||

| Goodwill | $12,000 | |

| Andrews, capital | $7,200 | |

| Bell, capital | 4,800 | |

| (2) | ||

| Cash | $14,000 | |

| Cohen, capital | $14,000 |

If the understatement of the capital of the old partners was attributable to excessive depreciation allowances, land appreciation, an increase in inventory value, or some combination of such factors, an appropriate adjustment of the asset or assets involved would be substituted for the charge to “goodwill.”

(iii) Investment at Less Than Book Value

Bonus Method.

If Cohen invests $8,000 for a one-fourth interest, it may indicate the willingness of the old partners to give Cohen a bonus to enter the firm.

Since the total capital is now $38,000, a one-fourth interest is $9,500 and the entry is:

| Cash | $8,000 | |

| Andrews, capital | 900 | |

| Bell, capital | 600 | |

| Cohen, capital | $9,500 |

Revaluation of Assets Method.

Under this method, the investment by Cohen of only $8,000 for a one-fourth interest may be taken to mean that the existing net assets are worth only $24,000. The overvaluation of $6,000 could be corrected by crediting the overvalued assets and charging Andrews and Bell in the income ratio. The entries would be:

| (1) | ||

| Andrews, capital | $3,600 | |

| Bell, capital | 2,400 | |

| Sundry assets | $6,000 | |

| (2) | ||

| Cash | $8,000 | |

| Cohen, capital | $8,000 |

(iv) Goodwill Method

A third method sometimes offered to handle this situation is the goodwill method, which assumes that the new partner contributes goodwill (of $2,000 in this case) in addition to the cash and is credited for the amount of his interest at book value ($10,000 in this case). This seems illogical, however, since it contradicts the original fact that Cohen's investment was to be $8,000.

(d) Settling with Withdrawing Partner Through Outside Funds

The withdrawal of a partner where settlement is effected by payments made from personal funds of the remaining partners directly to the retiring partner is illustrated by the firm of Adams, Bates, & Caldwell:

| Capital Balances | Income Ratio | |

| Adams | $30,000 | 50% |

| Bates | 24,000 | 30% |

| Caldwell | 16,000 | 20% |

| $70,000 | 100% |

(i) Sale at Book Value

If Caldwell retires, selling her interest at book value to the other partners in their income ratio and receiving payment from outside funds of Adams and Bates, the entry is:

| Caldwell, capital | $16,000 | |

| Adams, capital | $10,000 | |

| Bates, capital | 6,000 |

The total payment to Caldwell is $16,000, and payments by Adams and Bates are $10,000 and $6,000, respectively.

(ii) Sale at More Than Book Value

If payment to Caldwell exceeds book value, either the bonus or the goodwill method may be used.

Bonus Method.

If total payment to Caldwell is $18,000, the premium of $2,000 may be treated as a bonus to Caldwell. The entry to record the withdrawal of Caldwell is the same as above, and payment would be:

Goodwill Method.

In the following situation, Adams and Bates are willing to pay a total of $2,000 more than book value for Caldwell's interest. Since the latter receives 20 percent of the profits, this implies that assets are undervalued by $10,000. Under the goodwill or revaluation of assets method, all or part of this amount may be goodwill. The entries to record this situation are:

| (1) | ||

| Goodwill or sundry assets | $10,000 | |

| Adams, capital | $5,000 | |

| Bates, capital | 3,000 | |

| Caldwell, capital | 2,000 | |

| (2) | ||

| Caldwell, capital | $18,000 | |

| Adams, capital | $11,250 | |

| Bates, capital | 6,750 |

(iii) Sale at Less Than Book Value

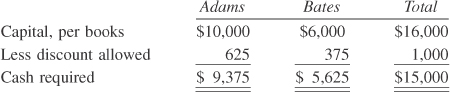

If Caldwell should agree to accept $15,000 for her interest, this is $1,000 less than book value.

Bonus Method.

The $1,000 may be considered to be a bonus to Adams and Bates. The entry would be the same as in the first example, but the cash payments would be calculated as follows:

Revaluation of Assets Method.

In this example, it can be argued under the revaluation of assets approach that the discount of $1,000 for a 20 percent share in firm profits implies an overstatement of book values of assets by $5,000. If this correction is to be made, the entries to adjust the books and record the subsequent withdrawal of Caldwell are:

| (1) | ||

| Adams, capital | $2,500 | |

| Bates, capital | 1,500 | |

| Caldwell, capital | 1,000 | |

| Sundry assets | $5,000 | |

| (2) | ||

| Caldwell, capital | $15,000 | |

| Adams, capital | $9,375 | |

| Bates, capital | 5,625 |

In preceding examples, the so-called bonus method and revaluation of assets method have been presented as alternatives. Although each method results in different capital account balances in the new firm that comes into being, it should be observed that the partners in the new firm are treated relatively the same under either method. This is subject to the basic qualification that the old partners who remain in the new firm must continue to share profits and losses as between themselves in the same ratio as before.

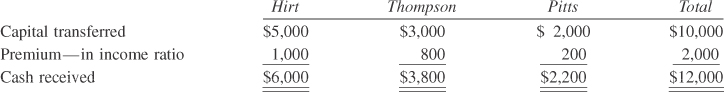

(e) Settlement Through Firm Funds

The withdrawal of a partner where settlement is to be made from funds of the business is illustrated by the firm of Arnold, Brown & Cline.

| Capital Balances | Income Ratio | |

| Arnold | $40,000 | 30% |

| Brown | 50,000 | 30 |

| Cline | 60,000 | 40 |

| $150,000 | 100% |

(i) Premium Paid to Retiring Partner

Payment is to be made to Cline from the assets of the partnership. Payment is $64,000, to be made one-half in cash and the balance in notes payable. Under one treatment, the premium of $4,000 is viewed as chargeable to the remaining partners in their income ratio. The entry is:

| Arnold, capital | $2,000 | |

| Brown, capital | 2,000 | |

| Cline, capital | 60,000 | |

| Cash | $32,000 | |

| Notes payable | 32,000 |

A second method treats the $4,000 premium as payment for Cline's share of the unrecognized goodwill of the firm. The following entry would be made:

| Goodwill | $4,000 | |

| Cline, capital | 60,000 | |

| Cash | $32,000 | |

| Notes payable | 32,000 |

A third possibility for recording the retirement of Cline is to recognize a total goodwill or asset revaluation implied by the premium paid for the retiring partner's share. Since a $4,000 premium was paid for a 40 percent share, total implied goodwill or asset revaluation is $10,000, and the entries are:

| (1) | ||

| Goodwill or sundry assets | $10,000 | |

| Arnold, capital | $3,000 | |

| Brown, capital | 3,000 | |

| Cline, capital | 4,000 | |

| (2) | ||

| Cline, capital | $64,000 | |

| Cash | $32,000 | |

| Notes payable | 32,000 |

Many accountants are inclined to approve of the first treatment on the grounds that it is “conservative.” Meigs, Johnson, and Keller state that it is “consistent with the current trend toward viewing a partnership as a continuing business entity, with asset valuations and accounting policies remaining undisturbed by the retirement of a partner.”8 The second treatment is supported by reference to the rule that it is proper to set up goodwill only when it has been purchased. The third interpretation relies on the idea that it is inconsistent to recognize the existence of an intangible asset and then to record it at only a fraction of the proper amount.

The accountant may distinguish between a payment for goodwill and one that represents a partner's share of the increase in value of one or more of the firm's assets. In the latter case, it is generally not reasonable to record only the increase attaching to the retiring partner's equity. Suppose, for example, that an inventory of merchandise has a market value on the date of settlement substantially above book value. Clearly, the most appropriate treatment here is that under which the inventory is adjusted to market value—the value at which it is in effect acquired by the new firm; to add to book value only the withdrawing partner's share of the increase would result in figures unsatisfactory from the standpoint both of financial accounting and operating procedure.

(ii) Discount Given by Retiring Partner

Assuming that Cline receives $57,000 for his interest in the firm and payment is made by equal amounts of cash and notes payable, two possible accounting treatments are available.

First, the discount of $3,000 may be credited to the remaining partners in their income ratio:

| Cline, capital | $60,000 | |

| Cash | $28,500 | |

| Notes payable | 28,500 | |

| Arnold, capital | 21,500 | |

| Brown, capital | 21,500 |

In the second method, the implied overvaluation of assets is recognized. Since Cline's share (40 percent) was purchased at a discount of $3,000, the total overvaluation of firm assets may be considered as $7,500. The following entries are made:

| (1) | ||

| Arnold, capital | $2,250 | |

| Brown, capital | 2,250 | |

| Cline, capital | 3,000 | |

| Sundry assets | $7,500 | |

| (2) | ||

| Cline, capital | $57,000 | |

| Cash | $28,500 | |

| Notes payable | 28,500 |

(f) Adjustment of Capital Ratios

Circumstances may arise in partnership affairs when it becomes desirable to adjust partners' capital account balances to certain ratios—most often the income ratio. This may happen in connection with the admission of a new partner, the withdrawal of a partner, or at some time when no change in personnel has occurred. Only a simple case involving a continuing firm is illustrated here.

Assume the following data for the firm of Emmett, Frye, and Gable:

| Capital Balances | Income Ratio | |

| Emmett | $50,000 | 50% |

| Frye | 25,000 | 30 |

| Gable | 15,000 | 20 |

| $90,000 | 100% |

If the partners wish to adjust their capital balances to the income ratio without changing total capital, it is obvious that Frye should pay $2,000 and Gable $3,000 directly to Emmett and that the entry should be:

| Emmet, capital | $5,000 | |

| Frye, capital | $2,000 | |

| Gable, capital | 3,000 |

Adjustment of the capital balances to the income ratio by the minimum additional investment into the firm (as distinguished from the preceding personal settlement) could, of course, be effected by the additional investment of $5,000 each by Frye and Gable.

20.4 Incorporation of a Partnership

According to Meigs, Johnson, and Keller:

Most successful partnerships give consideration at times to the possible advantages to be gained by incorporating. Among the advantages are limited liability, ease of attracting outside capital without loss of control, and possible tax savings.

A new corporation formed to take over the assets and liabilities of a partnership will usually sell stock to outsiders for cash either at the time of incorporation or at a later date. To assure that the former partners receive an equitable portion of the total capital stock, the assets of the partnership will need to be adjusted to fair market value before being transferred to the corporation. Any goodwill developed by the partnership should be recognized as part of the assets transferred.

The accounting records of a partnership may be modified and continued in use when the firm changes to the corporate form. As an alternative, the partnership books may be closed and a new set of accounting records established for the corporation.9

20.5 Partnership Realization and Liquidation

(a) Basic Considerations

A partnership may be disposed of either by selling the business as a unit or by the sale (realization) of the specific assets followed by the liquidation of the liabilities and final distribution of the remaining assets (usually cash) to the partners. A basic principle to be observed carefully in all such cases is that losses (or gains) in realization or sale must first be apportioned among the partners in the income ratio, following which, if outside creditors have been paid in full or cash reserved for that purpose, payments may be made according to the remaining capital balances of the partners.

Discussions of partnership liquidations usually point out that the proper order of cash distribution is: (1) payment of creditors in full, (2) payment of partners' loan accounts, and (3) payment of partners' capital accounts. Actually, the stated priority of the partners' loans appears to be a legal fiction. An established legal doctrine called the right of offset requires that any credit balance standing in a partner's name be set off against an actual or potential debit balance in his capital account. Application of this right of offset always produces the same final result as if the loan or undrawn salary account were a part of the capital balance at the beginning of the process. For this reason, no separate examples are given that include loan accounts. If they are encountered, they may be added to the capital account balance at the top of the liquidation statement. (The existence of partners' loan accounts might have an effect on profit sharing, however, in the sense that interest on partners' loans is usually provided for and profits might be shared in the average capital ratio; loans presumably would be excluded from the computation.)

Realization of all assets and liquidation of liabilities may be completed before any cash is distributed to partners. Or, if the realization process stretches over a considerable period of time, so-called installment liquidation may be employed.

(b) Liquidation by Single Cash Distribution

The next illustration demonstrates the realization of assets, payment of creditors, and final single cash distribution to the partners. Losses are first allocated to the partners in the income ratio, followed by cash payment to creditors and then to partners.

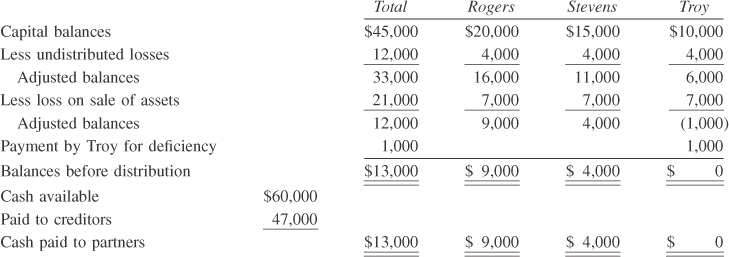

Rogers, Stevens, and Troy are partners with capital balances of $20,000, $15,000, and $10,000, respectively. Profits and losses are shared equally. On a particular date they find that the firm has assets of $80,000, liabilities of $47,000, and undistributed losses of $12,000. At this point the assets are sold for $59,000 cash. The proper distribution of the cash is as follows:

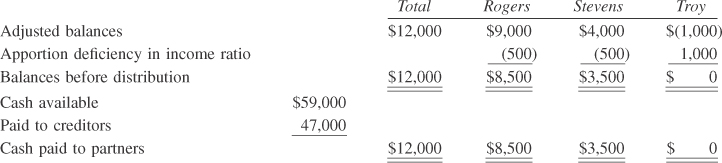

In this example, it was assumed that Troy was financially able to make up the $1,000 deficiency that appeared in his capital account. Only by making this payment does he bear his agreed share of the losses. If Troy had been personally insolvent and therefore unable to make the $1,000 payment, the statement from that point on would have taken this form:

Troy is now personally indebted to Rogers and Stevens in the amount of $500 each. Just how this debt would rank in the settlement of Troy's personal affairs depends on the state having jurisdiction. Under the UPA, his personal creditors (not including Rogers and Stevens) have prior claim to his personal assets; because he was said to have been personally insolvent, the presumption is that Rogers and Stevens would collect nothing. In a common-law state, a deficiency of this sort is considered to be a personal debt and would generally rank along with the other personal creditors. In this event, Rogers and Stevens would presumably make a partial recovery of the $500 due each of them.

(c) Liquidation by Installments

It is sometimes necessary to liquidate on an installment basis. Two of the many possible cases are illustrated—in the first there is no capital deficiency to any partner when the first cash distribution is made; in the second there is a possible deficiency of one partner at the time of the first cash distribution. The situation involving a final deficiency of a partner was discussed earlier in the partnership of Rogers, Stevens, and Troy. If this situation should appear in the winding up of an installment liquidation, its treatment would be the same as described there.

The role of the liquidator is especially important in the case of installment liquidation. In addition to the liquidator's obvious responsibility to see that outside creditors are paid and to convert the various assets into cash with a maximum gain or a minimum loss, he or she must protect the interests of the partners in their relationship to each other. Other than for reimbursement of liquidation expenses, no cash payment can be made to a partner, even on loan accounts or undrawn profits, except as the total standing to his or her credit exceeds his or her share of total possible losses on assets not yet realized. Improper payment by the liquidator might result in personal liability. Therefore, recovery could not be made from the partner who was overpaid.

(d) Capital Credits Only—No Capital Deficiency

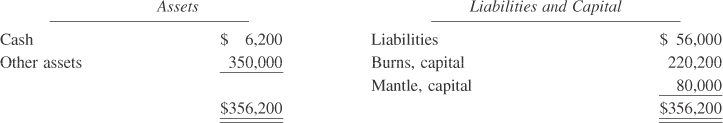

The balance sheet of Burns & Mantle as of April 30, when installment liquidation of the firm began, is presented next. The partners share profits and losses equally.

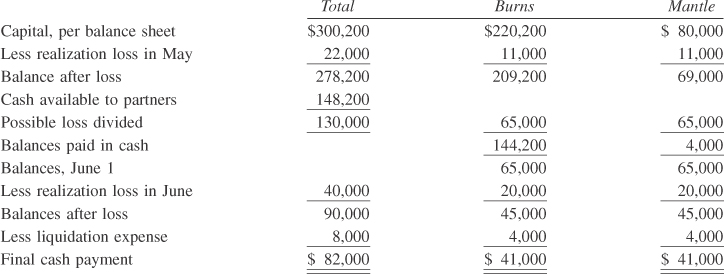

During May, assets having a book value of $220,000 are sold for cash of $198,000, and $39,000 is paid to creditors. During June, the remaining assets are sold for $90,000, the balance due creditors is paid, and liquidation expenses of $8,000 are paid. Distribution of cash to the partners should be made as follows:

Cash available to partners at May 31 is calculated as follows

In this example, the first payment of $148,200 reduces the capital claims to the profit and loss ratios, and all subsequent charges or credits to the partners' capital accounts are made accordingly.

(i) Capital Credits Only—Capital Deficiency of One Partner

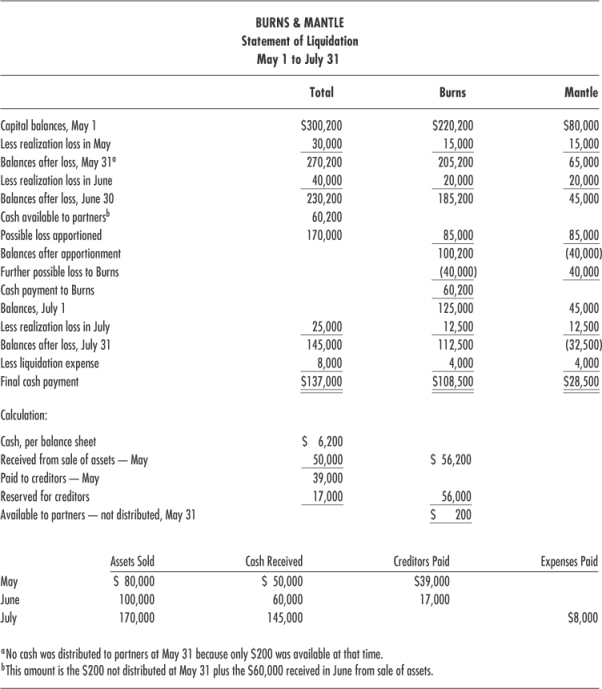

This situation is illustrated in Exhibit 20.3 using the previous balance sheet but assuming the next liquidation data:

Exhibit 20.3 Sample Statement of Liquidation

In Exhibit 20.3, each partner received in total the balance of his or her capital account per the balance sheet minus his or her share (50 percent) of realization losses and expenses, the same as if one final cash payment had been made on July 31. Note that if Mantle had had a loan account of, say, $20,000 and a capital balance of $60,000, the first cash distribution of $60,200 would still have gone entirely to Burns. At this point, after exercising the right of offset, Mantle would still have had a future possible deficiency of $40,000.

(ii) Installment Distribution Plan

A somewhat different approach to the problem of installment liquidation is illustrated below.

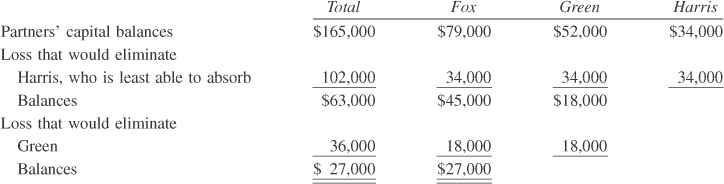

Fox, Green, and Harris are partners sharing profits equally. Shown next is the partnership balance sheet as of December 31, at which time it is decided to liquidate the firm by installments.

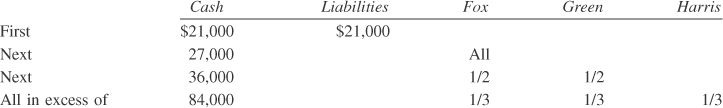

Using this balance sheet, computation of correct cash distribution is as follows:

The amount of the loss that will extinguish each partner's capital account is determined by dividing his or her capital account by his or her percentage of income and loss sharing. Hence, for Harris, this amount is $34,000 ÷ 33 1/3 percent, or $102,000.

From the computations, it is possible to prepare a schedule for the distribution of cash as follows:

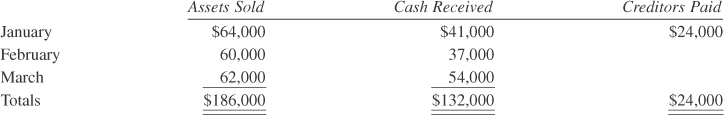

It is assumed that the $3,000 cash on hand on December 31 is used in payment of liabilities. The following liquidation data are given:

Based on these data, the application of the computations already made results in the following payments to creditors and partners:

20.6 Limited Partnerships

(a) Definition

Limited partnerships are business partnership structures that permit partners to invest capital with the proviso that there will be limited control over business operations and, accordingly, assumption of liability limited to the extent of capital contributions.

In general partnerships, the potential liability that can accrue to individual partners is unlimited. That unlimited liability has always been a major drawback of the partnership structure. Limited partnerships evolved to a great extent in order to overcome that disadvantage.

The legal provisions governing limited partnerships are provided by the Uniform Limited Partnership Act and the Revised Uniform Limited Partnership Act, which have been adopted in some form by each state government.

(b) Differences Between Limited Partnerships and General Partnerships

In addition to limitations on the liability of partners, limited partnerships differ from general partnerships in these ways:

- Limited partners have no participation in the management of the limited partnership.

- Limited partners may invest only cash or other assets in a limited partnership; they may not provide services as their investment.

- The surname of a limited partner may not appear in the name of the partnership.

(c) Formation of Limited Partnerships

The formation of limited partnerships is generally evidenced by a certificate filed with the county recorder of the principal place of business of the limited partnership rather than a partnership agreement such as that described in Section 20.1(e). Such certificates include many of the items present in the typical partnership contract of a general partnership. In addition, certificates must include:

- Name and residence of each general partner and limited partner

- Amount of cash and other assets invested by each limited partner

- Provision for return of a limited partner's investment

- Any priority of one or more limited partners over other limited partners

- Any right of limited partners to vote for election or removal of general partners, termination of the partnership, amendment of the certificate, or disposal of all partnership assets

Interests in limited partnerships are offered to prospective limited partners in units subject to the Securities Act of 1933. Thus, unless provisions of that act exempt a limited partnership, it must file a registration statement for the offered units with the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) and undertake to file periodic reports with the SEC. Large limited partnerships that engage in ventures such as oil and gas exploration and real estate development and issue units registered with the SEC are called master limited partnerships. The SEC has provided guidance for such registration and reporting in Industry Guide 5, Preparation of Registration Statements Relating to Interests in Real Estate Limited Partnerships.

(d) Accounting and Financial Considerations

As a general rule, the accounting records of limited partnerships are kept on a cash basis. However, the SEC requires that limited partnerships registrants prepare and file basic financial statements in conformity with generally accepted accounting principles (GAAP). For example, paragraph 10-S99-5 of ASC Topic 505-10, Equity, requires, for a public reporting company, the equity section of the limited partnership's balance sheet to distinguish between general partner and limited partner equity, with a separate statement of changes in partnership equity for each type of participation provided for each period for which a limited partnership income statement is presented.

The SEC staff also believes it is appropriate for a limited partnership registrant to include financial data on a tax basis of accounting, with an appropriate reconciliation of differences in major disclosure areas between tax and financial accounting. Whether GAAP-basis financial statements (along with the data necessary for income tax return preparation) should be distributed to the participants of SEC-reporting limited partnerships is a matter covered by the proxy rules.

ASC Topic 272, Limited Liability Entities, provides reporting guidance along with guidance on certain accounting issues regarding the application of existing authoritative literature for limited liability companies and limited liability partnerships (jointly referred to herein as LLCs).

(i) Financial Statement Reporting Issues

According to ASC Topic 272, a complete set of LLC financial statements should include:

- Statement of financial position as of the end of the reporting period

- Statement of operations for the period

- Statement of cash flows for the period

- Accompanying notes to financial statements

LLCs should also present information related to changes in members' equity for the period, either in a separate statement combined with the statement of operations or in the notes to the financial statements. The headings of an LLC's financial statements should identify clearly the financial statements as those of a limited liability company.

ASC Topic 272 stipulates that the financial statements of an LLC should be similar in presentation to those of a partnership. Since the owners of an LLC are referred to as members, the equity section in the statement of financial position should be titled members' equity. If more than one class of members exists, each having varying rights, preferences, and privileges, the LLC is encouraged to report the equity of each class separately within the equity section. If the LLC does not report the amount of each class separately within the equity section, it should disclose those amounts in the notes to the financial statements.

Even though a member's liability may be limited, if the total balance of the member's equity account or accounts described in the preceding paragraph is less than zero, a deficit should be reported in the statement of financial position.

If the LLC maintains separate accounts for components of members' equity (e.g., undistributed earnings, earnings available for withdrawal, or unallocated capital), ASC Topic 272 permits disclosure of those components, either on the face of the statement of financial position or in the notes to the financial statements.

If the LLC records amounts due from members for capital contributions, such amounts should be presented as deductions from members' equity. ASC Topic 272 notes that presenting such amounts as assets is inappropriate except in very limited circumstances when there is substantial evidence of ability and intent to pay within a reasonably short period of time.

Presentation of comparative financial statements is encouraged, but not required, by ASC Subtopic 205-10-45, Other Presentation Matters. If comparative financial statements are presented, amounts shown for comparative purposes must in fact be comparable with those shown for the most recent period, or any exceptions to comparability must be disclosed in the notes to the financial statements. Situations may exist in which financial statements of the same reporting entity for periods prior to the period of conversion are not comparable with those for the most recent period presented—for example, if transactions such as spin-offs or other distributions of assets occurred prior to or as part of the LLC's formation. In such situations, sufficient disclosure should be made so the comparative financial statements are not misleading. If the formation of the LLC results in a new reporting entity, a company should follow the guidance in paragraph 45-21 of ASC Topic 250, Accounting Changes and Error Corrections, and apply the change retrospectively to the financial statements of all prior periods presented to show financial information for the new reporting entity for those periods.

(ii) Financial Statement Disclosure Issues

ASC Topic 272 requires that these disclosures be made in the financial statements of a limited liability company:

- Any limitation of its members' liability should be described.

- The different classes of members' interests and the respective rights, preferences, and privileges of each class. If the LLC does not report separately the amount of each class in the equity section of the statement of financial position, those amounts should be disclosed.

- LLCs subject to income tax should make the disclosures required by ASC Topic 740, Income Taxes.

- If the LLC has a finite life, the date the LLC will cease to exist should be disclosed.

- For LLCs formed by combining entities under common control or by conversion from another type of entity, the notes to the financial statements for the year of formation should disclose that the assets and liabilities previously were held by a predecessor entity or entities. LLCs formed by combining entities under common control are encouraged to make the relevant disclosures in paragraphs 50-50-1 through 50-50-4 of ASC Topic 805, Business Combinations.

(iii) Accounting Issues

ASC Topic 272 requires that an LLC formed by combining entities under common control or by conversion from another type of entity initially should state its assets and liabilities at amounts at which they were stated in the financial statements of the predecessor entity or entities in a manner similar to a pooling of interests.

LLCs generally are classified as partnerships for federal income tax purposes. An LLC that is subject to federal (U.S.), foreign, state, or local (including franchise) taxes based on income should account for such taxes in accordance with ASC Topic 740.

ASC Topic 272 points out that in accordance with ASC Topic 740, an entity whose tax status in a jurisdiction changes from taxable to nontaxable should eliminate any deferred tax assets or liabilities related to that jurisdiction as of the date the entity ceases to be a taxable entity. ASC Topic 740 requires disclosure of significant components of income tax expense attributable to continuing operations including “adjustments of a deferred tax liability or asset for…a change in the tax status of the enterprise.”

20.7 Nonpublic Investment Partnerships

ASC Topic 946, Financial Services—Investment Companies, provides financial reporting guidance for investment partnerships that are exempt from SEC registration pursuant to the Investment Company Act of 1940 and defined as an investment company, except for:

- Investment partnerships that are brokers and dealers in securities subject to regulation under the Securities Exchange Act of 1934 (registered broker-dealers) and that manage funds only for those who are officers, directors, or employees of the general partner

- Investment partnerships that are commodity pools subject to regulation under the Commodity Exchange Act of 1974

ASC Topic 946 provides that the financial statements of an investment partnership, when prepared in conformity with GAAP, should, at a minimum, include a condensed schedule of investments in securities owned by the partnership at the close of the most recent period. Such a schedule should categorize investments by:

- Type (such as common stocks, preferred stocks, convertible securities, fixed-income securities, government securities, options purchased, options written, warrants, futures, loan participations, short sales, other investment companies, etc.)

- Country or geographic region

- Industry

The schedule should report the percentage of net assets that each such category represents and the total value and cost for each type of investment and country or geographic region. The schedule should also disclose the name, shares or principal amount, value, and type of:

- Each investment (including short sales) constituting more than 5 percent of net assets

- All investments in any one issuer aggregating more than 5 percent of net assets

In applying the 5 percent test, total long and total short positions in any one issuer should be considered separately.

Other investments (those that are individually 5 percent or less of net assets) should be aggregated without specifically identifying the issuers of such investments and be categorized by type, country or region, and industry. Also note that the foregoing information is required when the partnership's proportional share of any security owned by an individual investee exceeds 5 percent of the reporting partnership's net assets. Disclosure of the required information for such securities may be made either on the schedule itself or in a note thereto.

ASC Topic 946 also requires that investment partnerships present, among other things, separate disclosure of dividend income and interest income and realized and unrealized gains (losses) on securities for the period.

Investment companies organized as limited partnerships typically receive advisory services from the general partner. For such services, a number of partnerships pay fees chargeable as expenses to the partnership, whereas others allocate net income from the limited partners' capital accounts to the general partner's capital account, and still others employ a combination of the two methods. ASC Topic 946 states that the amounts of any such payments or allocations should be presented in either the statement of operations or the statement of changes in partners' capital, and the method of computing such payments or allocations should be described in the notes to the financial statements.

20.8 Joint Ventures

Forming a joint venture is a common way to create alliances and gain entry to or expand business operations in various domestic and foreign markets. As an alternative to a complete sale of a business, a company may form a joint venture if it is the company's desire to exit a business only partially while still maintaining an interest the rest of the business.

A company needs to use significant judgment and careful analysis regarding the accounting for joint ventures. Generally, the investors' accounting for the formation of a joint venture, including the receipt of noncash assets by the venture, provide for complex issues to sort through. Also adding to the complexities, a joint venture investor must evaluate its joint venture interests under the Variable Interest Entities Subtopics of ASC Topic 810, Consolidations, first to determine if the joint venture is a variable interest entity and whether one investor, or another enterprise with a variable interest in the entity, is the primary beneficiary and may be required to consolidate the joint venture.

Chapter 9 of this Handbook discusses the requirements to consolidate a variable interest entity.

(a) Definition

Joint ventures are partnerships formed when two or more parties pool resources for the purpose of undertaking a specific project, such as the development or marketing of a product. Joint ventures are owned, operated, and jointly controlled by a small group of owners or investors as separate business projects operated for the mutual benefit of the ownership group. Joint ventures may take the legal form of partnerships or they may be separately incorporated entities.

The owners or investors (venturers) in a joint venture may or may not have equal ownership interests in the venture. A venturer's share may range from as low as 5 percent or 10 percent to over 50 percent, but no less. All venturers usually participate in the overall management of the venture. Significant decisions generally require the consent of all venturers regardless of the percentage of ownership so that no individual venturer has unilateral control. It should be noted that an entity that is controlled by another entity is by definition not a joint venture. In addition, joint control, by itself, is not necessarily sufficient to use joint venture accounting.

ASC Topic 323, Investments—Equity Method and Joint Ventures, defines a corporate joint venture as follows:

A corporation owned and operated by a small group of entities (the joint venturers) as a separate and specific business or project for the mutual benefit of the members of the group. A government may also be a member of the group. The purpose of a corporate joint venture frequently is to share risks and rewards in developing a new market, product or technology; to combine complementary technological knowledge; or to pool resources in developing production or other facilities. A corporate joint venture also usually provides an arrangement under which each joint venturer may participate, directly or indirectly, in the overall management of the joint venture. Joint venturers thus have an interest or relationship other than as passive investors. An entity that is a subsidiary of one of the joint venturers is not a corporate joint venture. The ownership of a corporate joint venture seldom changes, and its stock is usually not traded publicly. A noncontrolling interest held by public ownership, however, does not preclude a corporation from being a corporate joint venture.

(b) Accounting by Joint Ventures

Regardless of their legal form of organization, joint ventures must maintain accounting records and prepare financial statements just like any other enterprise. The primary users of the joint ventures financial statements are the venturers, who need to record their share of the profit or loss of the venture and to value their investment in it. Most of the accounting principles and procedures used by joint ventures are the same as those used by other business enterprises.

The most significant accounting issue for most joint ventures is the recording of initial capital contributions, particularly noncash contributions. Such contributions should be recorded on the books of the venture at the fair value of the assets contributed on the date of contribution, unless the fair value of the assets is not readily or reliably determinable or the recoverability of that value is in doubt. This general rule does not apply, however, to assets contributed by a venturer who controls a venture. In those circumstances, the assets should be recorded on the books of the venture at the same amount at which they were carried on the venturer's books because there has been no effective change in control over the assets.

(c) Accounting for Investments in Joint Ventures

Since joint venturers have rights and obligations that may differ from their ownership percentages assuring them of significant influence even at ownership percentages of less than 20 percent, the application of customary equity or consolidation accounting is not always appropriate. Interests in incorporated joint ventures are accounted for in accordance with ASC Topic 323, which mandates use of the equity method. Accounting for interests in joint ventures that are organized as partnerships or undivided interests is discussed in ASC Subtopic 323-30, Partnerships, Joint Ventures, and Limited Liability Entities.

Chapter 9 in this Handbook discusses the requirements of the equity method of accounting.

1 J. I. Bogen, “Advantages and Disadvantages of Partnership,” in J. I. Bogen, ed., Financial Handbook, 4th ed., p. 5 (New York: Ronald Press, 1968).

2 N. M. Bedford, K. W. Perry, and A. H. Wyatt, Advanced Accounting—An Organization Approach (New York: John Wiley & Sons, 1979).

3 Bogen, “Advantages and Disadvantages of Partnership.”

4 M. Moonitz and L. H. Jordan, Accounting—An Analysis of Its Problems, 2 vols., rev. ed. (New York: Holt, Rinehart and Winston, 1963).

5 N. M. Bedford, Introduction to Modern Accounting (New York: Ronald Press, 1962).

6 R. L. Dixon, S. R. Hepworth, and W. A. Paton, Jr., Essentials of Accounting (New York: Macmillan, 1966).

7 W. H. Hoffman, Jr., ed., West's Federal Taxation: Corporations, Partnerships, Estates and Trusts (St. Paul, MN: West, 1978).

8 W. B. Meigs, C. E. Johnson, and T. F. Keller, Advanced Accounting I (New York: McGraw-Hill, 1966).

9 Ibid.

20.9 Sources and Suggested References

American Institute of Certified Public Accountants. Statement of Auditing Standards No. 45, Related Party Transactions. New York: Author, 1983.

Anderson, R. J. External Audit. Toronto: Pitman Publishing, 1977.

Bedford, N. M. Introduction to Modern Accounting. New York: Ronald Press, 1962.

Bedford, N. M., K. W. Perry, and A. H. Wyatt. Advanced Accounting—An Organization Approach. New York: John Wiley & Sons, 1979.

Blein, D. M., M. L. Fischer, and T. D. Skekel. Advanced Accounting. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons, 2004.

Bogen, J. I. “Advantages and Disadvantages of Partnership.” In Jules I. Bogen, ed., Financial Handbook, 4th ed. New York: Ronald Press, 1968.

Defliese, P. L., K. P. Johnson, and R. K. Macleod. Montgomery's Auditing, 9th ed. New York: Ronald Press, 1975.

Dixon, R. L., S. R. Hepworth, and W. A. Paton, Jr. Essentials of Accounting. New York: Macmillan, 1966.

Financial Accounting Standards Board. Statement of Financial Accounting Standards No. 57, Related Party Disclosures. Stamford, CT: Author, 1982.

Hoffman, W. H., Jr., ed. West's Federal Taxation: Corporations, Partnerships, Estates and Trusts. St. Paul, MN: West, 1978.

Jeter, D. C., and P. K. Chaney. Advanced Accounting. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons, 2010.

Meigs, W. B., C. E. Johnson, and T. F. Keller. Advanced Accounting. New York: McGraw-Hill, 1966.

Moonitz, M., and L. H. Jordan. Accounting—An Analysis of Its Problems, 2 vols., rev. ed. New York: Holt, Rinehart and Winston, 1963.