Chapter 16

Property, Plant, Equipment, and Depreciation

16.1 Nature of Property, Plant, and Equipment

(ii) Acquisition by Issuing Debt

(iii) Acquisition by Issuing Stock

(iv) Mixed Acquisition for Lump Sum

(b) Overhead on Self-Constructed Assets

(e) Cost of Assets Held for Research and Development Activities

(a) Authoritative Pronouncements

(b) Assets to Be Held and Used

16.4 Expenditures During Ownership

(a) Distinguishing Capital Expenditures from Operating Expenditures

(c) Replacements, Improvements, and Additions

(e) Rearrangement and Reinstallation

(f) Asbestos Removal or Containment

(g) Costs to Treat Environmental Contamination

(a) Retirements, Sales, and Trade-ins

16.6 Asset Retirement Obligations

(a) Initial Recognition and Measurement

(b) Subsequent Recognition and Measurement

(b) Basic Factors in the Computation of Depreciation

(a) Service Life as Distinguished from Physical Life

(b) Factors Affecting Service Life

(d) Statistical Methods of Estimating Service Lives

(e) Service Lives of Leasehold Improvements

(f) Revisions of Estimated Service Lives

(b) Property Under Construction

(c) Idle and Auxiliary Equipment

(ii) Fixed-Percentage-of-Declining-Balance Method

(iii) Double-Declining-Balance Method

(e) Depreciation for Partial Periods

(f) Change in Depreciation Method

(a) Sources of Depreciation Rates

(c) Effects of Replacements, Improvements, and Additions

16.12 Depreciation for Tax Purposes

(b) Modified Accelerated Cost Recovery System

(c) Additional First-Year Depreciation

16.13 Financial Statement Presentation and Disclosure

(c) Gain or Loss on Retirement

(d) Fully Depreciated and Idle Assets

(ii) Disclosures for Assets to Be Held and Used

(iii) Disclosures for Assets to Be Disposed Of

16.14 Sources and Suggested References

16.1 Nature of Property, Plant, and Equipment

(a) Definition

Property, plant, and equipment (PP&E) are presented as noncurrent assets in a classified balance sheet. The category includes such items as land, buildings, equipment, furniture, fixtures, tools, machinery, and leasehold improvements. It excludes intangibles and investments in affiliated companies.

(b) Characteristics

PP&E have several important characteristics:

- A relatively long life

- The production of income or services over their life

- Tangibility—having physical substance

(c) Authoritative Literature

Generally accepted accounting principles (GAAP) for PP&E have evolved without the promulgation of any Level A or B GAAP rule making on a comprehensive basis. Because of this lack of authoritative literature, many believe that diversity in practice has developed with respect to both the type of costs capitalized and the amounts.

In 2001, the Accounting Standards Executive Committee (AcSEC) of the American Institute of Certified Public Accountants (AICPA) issued an Exposure Draft (ED) of a Statement of Position (SOP) titled Accounting for Certain Costs and Activities Related to Property, Plant and Equipment. The proposal was not adopted, since the Financial Accounting Standards Board (FASB) indicated that it addressed significant issues that should be addressed by the FASB. Nevertheless, in the absence of subsequent action by the FASB, this document reflects the “best thinking” of the AcSEC at the time.

The proposal addresses accounting for costs related to initial acquisition, construction, improvements, betterments, additions, repairs and maintenance, planned major maintenance, turnaround, overhauls, and other similar costs related to PP&E, outlined as follows:

- Accrual of a liability before incurring the costs for a planned major maintenance activity

- Deferral and amortization of the cost of a planned major maintenance activity

- Current recognition of additional depreciation to cover future costs of a planned major maintenance activity

- The capitalization criteria would have prohibited capitalization of indirect costs, overhead, and general and administrative costs, which many entities currently capitalize as a part of their PP&E cost.

- Many entities currently use the methods prohibited under the section titled “Planned Major Maintenance Activities” to account for plant turnarounds and other major maintenance activities.

- Requirements to use component accounting would have effectively prohibited entities from using group and composite methods of accounting for depreciation.

Since the withdrawal of this ED, the FASB has not taken action in providing guidance on these issues.

16.2 Cost

PP&E usually are recorded at cost, defined as the amount of consideration paid or incurred to acquire or construct an asset. Cost consists of several elements. Welsch and Zlatkovich explain:

The capitalizable costs include the invoice price (less discounts), plus other costs such as sales tax, insurance during transit, freight, duties, ownership searching, ownership registration, installation, and break-in costs.1

(a) Determining Cost

Generally, three principles are followed for determining the cost of an asset:

(i) Acquisition by Exchange

PP&E may be acquired by exchange as well as by purchase. In that case, the applicable accounting requirements are set forth in paragraph 3c of Accounting Principles Board (APB) Opinion No. 29, Accounting for Nonmonetary Transactions, (FASB Accounting Standard Codification [ASC] 845-10) which defines an exchange as “a reciprocal transfer between an enterprise and another entity that results in the enterprise's acquiring assets or services or satisfying liabilities by surrendering other assets or services or incurring other obligations.”

After defining nonmonetary assets (par. 3b) to include PP&E, Opinion No. 29 (par. 18) (FASB Accounting Standard Codification [ASC] 845-10)2 further provides the general rule:

Accounting for nonmonetary transactions should be based on the fair values of the assets (or services) involved… . Thus, the cost of a nonmonetary asset acquired in exchange for another nonmonetary asset is the fair value of the asset surrendered to obtain it, and a gain or loss should be recognized on the exchange. The fair value of the asset received should be used to measure the cost if it is more clearly evident than the fair value of the asset surrendered.

However, paragraph 21 of Opinion No. 29 (FASB ASC 845-10) recognizes an exception to its general rule if an exchange of nonmonetary assets “is not essentially the culmination of an earning process.” In that case, the accounting “should be based on the recorded amount (after reduction, if appropriate, for an indicated impairment of value) of the nonmonetary asset relinquished.”

Among the exchanges of nonmonetary assets that do not culminate the earning process, paragraph 21b of Opinion No. 29 (FASB ASC 845-10) includes “an exchange of a productive asset [defined to include property, plant, and equipment] not held for sale in the ordinary course of business for a similar productive asset or an equivalent interest in the same or similar productive asset.”

However, the rule about basing exchanges of productive (nonmonetary) assets on recorded amounts has its own exception if the exchange includes monetary consideration. In that case, paragraph 22 of Opinion No. 29 (FASB ASC 845-10) states:

The Board believes that the recipient of the monetary consideration has realized gain on the exchange to the extent that the amount of the monetary receipt exceeds a proportionate share of the recorded amount of the asset surrendered. The portion of the cost applicable to the realized amount should be based on the ratio of the monetary consideration to the total consideration received (monetary consideration plus the estimated fair value of the nonmonetary asset received) or, if more clearly evident, the fair value of the nonmonetary asset transferred. The Board further believes that the entity paying the monetary consideration should not recognize any gain on [an exchange not culminating the earning process] but should record the asset received at the amount of the monetary consideration paid plus the recorded amount of the nonmonetary asset surrendered. If a loss is indicated by the terms of [an exchange not culminating the earning process], the entire indicated loss on the exchange should be recognized.

FASB's Emerging Issues Task Force (EITF) later reached a consensus (EITF Issue No. 86-29; FASB ASC 845-10) that an exchange of nonmonetary assets should be considered a monetary (rather than nonmonetary) transaction if monetary consideration is significant, and agreed that “significant” should be defined as at least 25 percent of the fair value of the exchange.

(ii) Acquisition by Issuing Debt

If PP&E are acquired in exchange for payables or other contractual obligations to pay money (referred to collectively as notes), paragraph 12 of Accounting Principles Board (APB) Opinion No. 21, Interest on Receivables and Payables (FASB ASC 310-10) states:

There should be a general presumption that the rate of interest stipulated by the parties to the transaction represents fair and adequate compensation to the supplier for the use of the related funds.

However, the Opinion continues:

That presumption … must not permit the form of the transaction to prevail over its economic substance and thus would not apply if (1) interest is not stated, or (2) the stated interest rate is unreasonable … or (3) the stated face amount of the note is materially different from the current cash sales price for the same or similar items or from the market value of the note at the date of the transaction.

In any of these circumstances, both the assets acquired and the note should be recorded at the fair value of the assets or at the market value of the note, whichever can be more clearly determined. If the amount recorded is not the same as the face value of the note, the difference is a discount or premium, which should be accounted for as interest over the life of the note. If there is no established price for the assets acquired and no evidence of the market value of the note, the amount recorded should be determined by discounting all future payments on the note using an imputed rate of interest.

In selecting the imputed rate of interest to be used, paragraph 14 of APB Opinion No. 21 (FASB ASC 835-30) states that consideration should be given to:

(a) An approximation of the prevailing market rates for the source of credit that would provide a market for sale or assignment of the note; (b) the prime or higher rate for notes which are discounted with banks, giving due weight to the credit standing of the maker; (c) published market rates for similar quality bonds; (d) current rates for debentures with substantially identical terms and risks that are traded in open markets; and (e) the current rate charged by investors for first or second mortgage loans on similar property.

(iii) Acquisition by Issuing Stock

Assets acquired by issuing shares of stock should be recorded at either the fair value of the shares issued or the fair value of the property acquired, whichever is more clearly evident.

Smith and Skousen further explain:

When securities do not have an established market value, appraisal of the acquired assets by an independent authority may be required to arrive at an objective determination of their fair market value. If satisfactory market values cannot be obtained for either securities issued or the assets acquired, values may have to be established by the board of directors for accounting purposes. The source of the valuation should be disclosed on the balance sheet.3

(iv) Mixed Acquisition for Lump Sum

Several assets may be acquired for a lump-sum payment. This type of acquisition is often called a basket purchase. It is essential to allocate the joint cost carefully, because the assets may include both depreciable and nondepreciable assets, or the depreciable assets may be depreciated at different rates.

Welsch and Zlatkovich discuss the methods of allocating joint costs:

The allocation of the purchase price should be based on some realistic indicator of the relative values of the several assets involved, such as current appraised values, tax assessment, cost savings, or the present value of estimated future earnings.4

(v) Donated Assets

PP&E may be donated to an entity. The accounting for such donations is addressed by Statement of Financial Accounting Standards (SFAS) No. 116, Accounting for Contributions Received and Contributions Made. Paragraph 8 (FASB ASC 958-605) concludes that donated PP&Eshould be measured at fair value.

Paragraph 19 (FASB ASC 958-605) provides guidance for determining the fair value of donated assets and indicates that quoted market prices, if available, are the best evidence of the fair value. It further indicates that if quoted market prices are not available, fair value may be estimated based on quoted market prices for similar assets, independent appraisals, or valuation techniques, such as the present value of estimated cash flows.

(b) Overhead on Self-Constructed Assets

Companies often construct their own buildings and equipment. Materials and labor directly identifiable with the construction are part of its cost.

As to whether overhead should be included in the cost of construction, Lamden, Gerboth, and McRae suggest:

In the absence of compelling evidence to the contrary, overhead costs considered to have “discernible future benefits” for the purpose of determining the cost of inventory should be presumed to have “discernible future benefits” for the purpose of determining the cost of a self-constructed depreciable asset.5

Mosich and Larsen agree and go on to discuss two alternative views as to what overhead should be included:

Allocate Only Incremental Overhead Costs to the Self-Constructed Asset. This approach may be defended on the grounds that incremental overhead costs represent the relevant cost that management considered in making the decision to construct the asset. Fixed overhead costs, it is argued, are period costs. Because they would have been incurred in any case, there is no relationship between the fixed overhead costs and the self-constructed project. This approach has been widely used in practice because it does not distort the cost of normal operations.

Allocate a Portion of All Overhead Costs to the Self-Constructed Asset. The argument for this approach is that the proper function of cost allocation is to relate all costs incurred in an accounting period to the output of that period. If an enterprise is able to construct an asset and still carry on its regular activities, it has benefited by putting to use some of its idle capacity, and this fact should be reflected in larger income. To charge the entire overhead to only a portion of the productive activity is to disregard facts and to understate the cost of the self-constructed asset. This line of reasoning has considerable merit.6

(c) Interest Capitalization

Paragraph 6 of SFAS No. 34, Capitalization of Interest Cost (FASB ASC 835-20) states:

The historical cost of acquiring an asset includes the costs necessarily incurred to bring it to the condition and location necessary for its intended use. If an asset requires a period of time in which to carry out the activities necessary to bring it to that condition and location, the interest cost incurred during that period as a result of expenditures for the asset is a part of the historical cost of acquiring the asset.

Paragraph 9 (FASB ASC 835-20) describes the assets that qualify for interest capitalization:

- Assets that are constructed or otherwise produced for an enterprise's own use (including assets constructed or produced for the enterprise by others for which deposits or progress payments have been made)

- Assets intended for sale or lease that are constructed or otherwise produced as discrete projects (e.g., ships or real estate developments)

The amount of interest capitalized is computed by applying an interest rate to the average amount of accumulated expenditures for the asset during the period. To the extent that specific borrowings are associated with the asset, the interest rate on those borrowings may be used. Otherwise, the interest rate should be the weighted average rate applicable to other borrowings outstanding during the period. In no event should the total interest capitalized exceed total interest costs incurred for the period. Imputing interest costs on equity is not permitted.

Descriptions of capitalized interest are often seen in footnotes, such as the next example from 1989 financial statements:

Delta Air Lines, Inc.

Notes to Consolidated Financial Statements

Note 1. Summary of Significant Accounting Policies

Interest Capitalized—Interest attributable to funds used to finance the acquisition of new aircraft and construction of major ground facilities is capitalized as an additional cost of the related asset. Interest is capitalized at the Company's average interest rate on long-term debt or, where applicable, the interest rate related to specific borrowings. Capitalization of interest ceases when the property or equipment is placed in service.

(d) Cost of Land

Determining the cost of land presents particular problems, as described by Pyle and Larson:

When land is purchased for a building site, its cost includes the amount paid for the land plus real estate commissions. It also includes escrow and legal fees, fees for examining and insuring the title, and any accrued property taxes paid by the purchaser, as well as expenditures for surveying, clearing, grading, draining, and landscaping. All are part of the cost of the land. Furthermore, any assessments incurred at the time of purchase or later for such things as the installation of streets, sewers, and sidewalks should be debited to the Land account because they add a more or less permanent value to the land.7

Excavation of land for building purposes, however, is chargeable to buildings rather than to land.

See Chapter 31 for a discussion of the accounting for land acquired as part of a real estate operation.

(i) Purchase Options

If a company acquires an option to purchase land and later exercises that option, the cost of the option generally becomes part of the cost of the land. Even if an option lapses without being exercised, its cost can be capitalized if the option is one of a series of options acquired as part of an integrated plan to acquire a site. In that case, if any one of the options is exercised, the cost of all may be capitalized as part of the cost of the site.

(ii) Interest

Paragraph 11 of SFAS No. 34 (FASB ASC 835-20) describes the proper accounting for interest cost related to land:

Land that is not undergoing activities necessary to get it ready for its intended use is not [an asset qualifying for interest capitalization]. If activities are undertaken for the purpose of developing land for a particular use, the expenditures to acquire the land qualify for interest capitalization while those activities are in progress. The interest cost capitalized on those expenditures is a cost of acquiring the asset that results from those activities. If the resulting asset is a structure, such as a plant or a shopping center, interest capitalized on the land expenditures is part of the acquisition cost of the structure. If the resulting asset is developed land, such as land that is to be sold as developed lots, interest capitalized on the land expenditures is part of the acquisition cost of the developed land.

(iii) Other Carrying Charges

Paragraph 6 of SFAS No. 67, Accounting for Costs and Initial Rental Operations of Real Estate Projects (FASB ASC 970-340) states:

Costs incurred on real estate for property taxes and insurance shall be capitalized as property cost only during periods in which activities necessary to get the property ready for its intended use are in progress. Costs incurred for such items after the property is substantially complete and ready for its intended use shall be charged to expense as incurred.

Even though the scope of the Statement excludes “real estate developed by an enterprise for use in its own operations, other than for sale or rental,” this guidance is followed in capitalizing carrying charges generally.

(e) Cost of Assets Held for Research and Development Activities

Although paragraph 12 of SFAS No. 2, Accounting for Research and Development Costs (FASB ASC 730-10) generally requires that research and development costs be charged to expense when incurred, it makes an exception (par. 11a; FASB ASC 730-10) for “the costs of materials (whether from the enterprise's normal inventory or acquired specially for research and development activities) and equipment or facilities that are acquired or constructed for research and development activities and that have alternate future uses (in research and development projects or otherwise).” These costs, the Statement says, “shall be capitalized as tangible assets when acquired or constructed.”

16.3 Impairment of Value

(a) Authoritative Pronouncements

SFAS No. 144, Accounting for the Impairment or Disposal of Long-Lived Assets (FASB ASC 360-10), prescribes the accounting for the impairment of long-lived assets, including PP&E. The SFAS applies to PP&E that is “held and used” and to PP&E that is held for disposal (referred to in the Statement as assets to be disposed of).

(b) Assets to Be Held and Used

SFAS No. 144 (FASB ASC 360-10) requires this three-step approach for recognizing and measuring the impairment of assets to be held and used:

(i) Recognition

SFAS No. 144 (FASB ASC 360-10) requires that PP&E that are used in operations be reviewed for impairment whenever events or changes in circumstances indicate that the carrying amount of the assets might not be recoverable—that is, information indicates that an impairment might exist. Accordingly, companies do not need to perform a periodic assessment of assets for impairment in the absence of such information. Instead, companies would assess the need for an impairment write-down only if an indicator of impairment is present. The SFAS lists these examples of events or changes in circumstances that may indicate to management that an impairment exists:

- A significant decrease in the market price of a long-lived asset (asset group)

- A significant adverse change in the extent or manner in which an asset (asset group) is used or in its physical condition

A significant adverse change in legal factors or in the business climate that could affect the value of a long-lived asset (asset group), including an adverse action or assessment by a regulator An accumulation of costs significantly in excess of the amount originally expected for the acquisition or construction of a long-lived asset (asset group) A current-period operating or cash flow loss combined with a history of operating or cash flow losses or a projection or forecast that demonstrates continuing losses associated with the use of a long-lived asset (asset group) A current expectation that, more likely than not, a long-lived asset (asset group) will be sold or otherwise disposed of significantly before the end of its previously estimated useful life. The term more likely than not refers to a level of likelihood that is more than 50 percent. The preceding list is not all-inclusive, and there may be other events or changes in circumstances, including circumstances that are peculiar to a company's business or industry, indicating that the carrying amount of a group of assets might not be recoverable and thus impaired. If indicators of impairment are present, companies must then disaggregate the assets by grouping them at the lowest level for which there are identifiable cash flows that are largely independent of the cash flows of other groups of assets. Then future cash flows expected to be generated from the use of those assets and their eventual disposal must be estimated. That estimate is comprised of the future cash inflows expected to be generated by the assets less the future cash outflows expected to be necessary to obtain those inflows. If the estimated undiscounted cash flows are less than the carrying amount of the assets, an impairment exists, and an impairment loss must be calculated and recognized.

The FASB recognized that certain long-lived assets could not be readily identified with specific cash flows (e.g., a corporate headquarters building and certain property and equipment of not-for-profit organizations). In those situations, the assets should be evaluated for impairment at an entity-wide level. If management estimates that the entity as a whole will generate cash flows sufficient to recover the carrying amount of all assets used in its operations, including its corporate headquarters building, no impairment loss would be recognized.

SFAS No. 144 (FASB ASC 360-10) provides little guidance for estimating future cash flows, even though the accounting consequences of small changes in those estimates could be significant. Accordingly, estimating future undiscounted cash flows requires a great deal of judgment. Companies must make their best estimate based on reasonable and supportable assumptions and projections that are applied on a consistent basis. The Statement indicates that all available evidence should be considered in developing the cash flow estimates, and the weight given that evidence should be commensurate with the extent to which the evidence can be verified objectively.

(ii) Measurement

Once it is determined that an impairment exists, an impairment loss is calculated based on the excess of the carrying amount of the asset over the asset's fair value.

In September 2006, the FASB issued SFAS Statement No. 157, Fair Value Measurements (FASB ASC 820-10). It defines fair value, establishes a framework for measuring fair value in GAAP, and expands disclosure about fair value measurements. The effective date of SFAS No. 157 is for financial statements of fiscal years beginning after November 15, 2007. SFAS No. 157 (FASB ASC 820-10) defines fair value as “the price that would be received to sell an asset or paid to transfer a liability in an orderly transaction between market participants at the measurement date.” FAS 157 (FASB ASC 820-10) discusses changes to current practice related to the definition of fair value and the methods used to measure fair value and expands disclosures about fair value measurements.

FAS 157 (FASB ASC 820-10) clarifies that the exchange price is the price in an orderly transaction between market participants to sell the asset or transfer the liability in the market in which the reporting entity would transact for the asset or liability (i.e., the principal or most advantageous market for the asset or liability). The transaction to sell the asset or transfer the liability is a hypothetical transaction at the measurement date, considered from the perspective of a market participant that holds the asset or owes the liability. Therefore, the definition focuses on the price that would be received to sell the asset or paid to transfer the liability (an exit price), not the price that would be paid to acquire the asset or received to assume the liability (an entry price).

Once management determines that an asset (or a group of assets) is impaired and the asset is written down to fair value, the reduced carrying amount represents the new cost basis of the asset. As a result, subsequent depreciation of the asset is based on the revised carrying amount, and companies are prohibited from reversing the impairment loss should facts and circumstances change or conditions improve in the future.

(c) Assets to Be Disposed Of

SFAS No. 144 (FASB ASC 360-10) indicates that assets to be disposed of other than by sale (e.g., abandonment, exchange for another long-lived asset) should continue to be classified as held and used until they are disposed of. An asset or asset group to be disposed of by sale should be classified as held for sale during the period in which all of these criteria are met:

- Management commits to a plan of disposal.

- The asset is available for immediate sale.

- An active program to locate a buyer has been initiated.

- Sale of the asset within one year is probable.

- The asset is being actively marketed for sale at a reasonable price.

- Actions required to complete the plan indicate that it is unlikely the plan will be significantly modified or withdrawn.

If at any time while an asset is classified as held for sale any of these criteria are no longer met or the entity's plans change, the asset should be reclassified to the held and used category. The asset should be reclassified at the lower of the original carrying amount immediately before it is transferred to held for sale (adjusted for any depreciation expense that would have been recognized had the asset been continuously classified as held and used) or fair value at the date of the change in status. An asset classified as held for sale should be measured at the lower of its carrying amount or fair value less incremental direct costs of sale. An asset classified as held for sale should not be depreciated. SFAS No. 144 (FASB ASC 360-10) requires subsequent revisions to the carrying amount of assets classified as held for sale if the estimate of fair value less cost to sale changes during the holding period. After an initial write-down of an asset to fair value less cost to sell, the carrying amount can be increased or decreased depending on changes in the fair value less cost to sell of the asset. However, an increase in carrying value cannot exceed the carrying amount of the asset immediately before its classification into the held for sale category.

SFAS No. 144 (FASB ASC 360-10) also supersedes APB Opinion No. 30 (FASB ASC 225-20) with respect to discontinued operations. The Statement indicates that the results of operations relating to assets to be disposed of comprising a component of an entity should be classified as discontinued operations if both of the next conditions are met:

A component of an entity is defined as operations and cash flows that can be clearly distinguished from the rest of the entity both operationally and for financial reporting purposes. The definition of component of an entity under SFAS No. 144 (FASB ASC 360-10) is much broader than the APB Opinion No. 30 (FASB ASC 225-20) definition of a segment of a business. Accordingly, many more discontinued operations will be reported under SFAS No. 144 (FASB ASC 360-10) than previously. For example, if a real estate entity disposes of an individual property, that property would likely qualify as a component of an entity under SFAS No. 144 (FASB ASC 360-10) but generally would not have qualified as a disposal of a segment of a business under APB Opinion No. 30 (FASB ASC 225-20).

16.4 Expenditures During Ownership

(a) Distinguishing Capital Expenditures from Operating Expenditures

After PP&E have been acquired, additional expenditures are incurred to keep the assets in satisfactory operating condition. Certain of these expenditures—capital expenditures—are added to the asset's cost. The remainder—operating expenditures (sometimes called revenue expenditures)—are charged to expense.

Kohler defines a capital expenditure in two ways:

1. An expenditure intended to benefit future periods, in contrast to a revenue expenditure, which benefits a current period; an addition to a capital asset. The term is generally restricted to expenditures that add fixed-asset units or that have the effect of increasing the capacity, efficiency, life span, or economy of operation of an existing fixed asset.

2. Hence, any expenditure benefiting a future period.8

Although the distinction is important, immaterial capital expenditures can be charged to expense.

Expenditures during ownership fall into four categories:

(b) Maintenance and Repairs

The terms maintenance and repairs generally are used interchangeably. However, Kohler defines them separately, and his definitions are useful in identifying expenditures that should be accounted for as maintenance and repairs. He defines maintenance as:

The keeping of property in operable condition; also, the expense involved. Maintenance costs include outlays for (a) labor and supplies; (b) the replacement of any part that constitutes less than a retirement unit; and (c) major overhauls the items of which may involve elements of the first two classes. Items falling under (a) and (b) are always regarded as operating costs, chargeable to current expense directly or through the medium of a maintenance reserve…. Costs under (c) are similarly treated unless they include the replacement of a retirement unit the outlay for which is normally capitalized. [p. 315]

He defines repairs as:

The restoration of a capital asset to its full productive capacity, or a contribution thereto, after damage, accident, or prolonged use, without increase in the asset's previously estimated service life or productive capacity. The term includes maintenance primarily “preventive” in character, and capitalizable extraordinary repairs. [p. 428]

(i) Accounting Alternatives

As Kohler states, except for extraordinary repairs (or major overhauls), discussed in the next subsection, maintenance and repairs expenditures are accounted for in two ways:

1. Charge to expense when the cost is incurred

2. Charge to a maintenance allowance account

Charge to Expense When the Cost Is Incurred. Since ordinary maintenance and repairs expenditures are regarded as operating costs, they are usually charged directly to expense when incurred.

Charge to a Maintenance Allowance Account. The charge to expense may be accomplished through an allowance account. In some cases, the purpose of an allowance account is to equalize monthly repair costs within a year. Total repair costs are estimated at the beginning of the year, and the total is spread evenly throughout the year. The difference between the estimated and actual amounts at the end of the year is usually spread retroactively over all months of the year rather than being absorbed entirely by the last month. In the balance sheet, this allowance account may be treated as a reduction of the related asset account.9

This latter approach is supported by paragraph 16a of APB Opinion No. 28, Interim Financial Reporting (FASB ASC 270-10):

When a cost that is expensed for annual reporting purposes clearly benefits two or more interim periods (e.g., annual major repairs), each interim period should be charged for an appropriate portion of the annual cost by the use of accruals or deferrals.

In other cases, the purpose of a maintenance allowance account is to charge the costs of major repairs over the entire period benefited, which may be longer than one year. When airlines acquire new aircraft, for example, they begin immediately to accrue the cost of the first engine overhaul, which usually is scheduled for more than one year hence. As illustrated by the next example from 1987 financial statements, the accrual charges are credited to a maintenance allowance account, which is then charged for cost of the overhaul.

Stateswest Airlines, Inc. and Subsidiaries

Notes to Consolidated Financial Statements

Summary of Significant Accounting Policies

Engine Overhaul Reserve. For all the leased aircraft, the Company accrues maintenance expense, on the basis of hours flown, for the estimated cost of engine overhauls.

(ii) Extraordinary Repairs

Welsch, Anthony, and Short define extraordinary repairs as repairs that

… occur infrequently, involve relatively large amounts of money, and tend to increase the economic usefulness of the asset in the future because of either greater efficiency or longer life, or both. They are represented by major overhauls, complete reconditioning, and major replacements and betterments.10

Because expenditures for extraordinary repairs increase the future economic usefulness of an asset, they benefit future periods and are therefore capital expenditures. Ordinarily, they are added to the related asset account, as illustrated in the next example from 1987 financial statements.

Air Midwest, Inc. and Subsidiaries

Notes to Consolidated Financial Statements

Note 1. Summary of Significant Accounting Policies

d. Maintenance and Repairs

Major renewals and betterments are capitalized and depreciated over the remaining useful life of the asset.

Some authorities recommend that the expenditures for extraordinary repairs be charged against the accumulated depreciation account. The rationale for charging accumulated depreciation is provided by Smith and Skousen:

Often it is not possible to identify the cost related to a specific part of an asset. In these instances, by debiting accumulated depreciation, the undepreciated book value is increased without creating a build-up of the gross asset values.11

Other authorities argue against debiting accumulated depreciation for extraordinary repairs because the accumulated depreciation on the asset may be less than the cost of the repairs and because the practice allows the original cost of any parts replaced to remain in the asset account.

(c) Replacements, Improvements, and Additions

Replacements, improvements, and additions are related concepts. Kohler defines a replacement as “the substitution of one fixed asset for another, particularly of a new asset for an old, or of a new part for an old part.” He defines an improvement (which he calls a “betterment”) as “an expenditure having the effect of extending the useful life of an existing fixed asset, increasing its normal rate of output, lowering its operating cost, increasing rather than merely maintaining efficiency or otherwise adding to the worth of benefits it can yield.”12 Improvements ordinarily do not increase the physical size of the productive facility. Such an increase is an addition.

The distinctions among replacement, improvement, and addition notwithstanding, the accounting for all three is substantially the same. Expenditures for them are capital expenditures, that is, additions to PP&E. (In practice, immaterial amounts are often charged to expense.) The cost of existing assets that are replaced, together with their related accumulated depreciation accounts, is eliminated from the accounts.

(d) Rehabilitation

Expenditures to rehabilitate buildings or equipment purchased in a rundown condition with the intention of rehabilitating them should be capitalized. Normally the acquisition price of a rundown asset is less than that of a comparable new asset, and the rehabilitation expenditures benefit future periods. Capitalization of the expenditures is therefore appropriate. However, the total capitalized cost of the asset should not exceed the amount recoverable through operations.

When rehabilitation takes place over an extended period, care should be taken to distinguish between the cost of rehabilitation and the cost of maintenance.

(e) Rearrangement and Reinstallation

Kieso and Weygandt describe rearrangement and reinstallation costs and the accounting for them:

Rearrangement and reinstallation costs, which are expenditures intended to benefit future periods, are different from additions, replacements and improvements. An example is the rearrangement and reinstallation of a group of machines to facilitate future production. If the original installation cost and the accumulated depreciation taken to date can be determined or estimated, the rearrangement and reinstallation cost can be handled as a replacement. If not, which is generally the case, the new costs if material in amount should be capitalized as an asset to be amortized over those future periods expected to benefit. If these costs are not material, if they cannot be separated from other operating expenses, or if their future benefit is questionable, they instead should be expensed in the period in which they are incurred.13

(f) Asbestos Removal or Containment

Removal or containment of asbestos is regulated and required by various federal, state, and local laws. The diversity of practice in capitalizing or expensing the cost of asbestos removal or containment resulted in asbestos removal being considered by the EITF. Issue No. 89-13 (FASB ASC 410-20) asked “whether the costs incurred to treat asbestos when a property with a known asbestos problem is acquired should be capitalized or charged to expense” and “whether the costs incurred to treat asbestos in an existing property should be capitalized or charged to expense.”

The EITF concluded that the costs incurred to treat asbestos within a reasonable time period after a property with a known asbestos problem is acquired should be capitalized as part of the cost of the acquired property subject to an impairment test for that property. The consensus on existing property was not as conclusive and stated that the costs “may be capitalized as a betterment subject to an impairment test for that property.”

The EITF also reached a consensus that when costs are incurred in anticipation of a sale of property, they should be deferred and recognized in the period of the sale to the extent that those costs can be recovered from the estimated sales price.

The SEC observer at the EITF meeting noted that regardless of whether asbestos treatment costs are capitalized or charged to expense, Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) registrants should disclose significant exposure for asbestos treatment costs in “Management's Discussion and Analysis.”

The EITF in Issue No. 90-8 (FASB ASC 410-30) affirmed the Issue No. 89-13 (FASB ASC 410-30) consensus but did not provide further guidance on capitalizing or charging to expense the costs incurred on existing properties. In practice, there continues to be wide diversity of the types of costs capitalized, if any, and the accrual of costs to remove or contain asbestos in existing properties.

(g) Costs to Treat Environmental Contamination

Costs to remove, contain, neutralize, or prevent existing or future environmental contamination may be incurred voluntarily or as required by federal, state, and local laws. In Issue No. 90-8 (FASB ASC 410-30), the EITF considered whether environmental contamination treatment costs should be capitalized or charged to expense.

The EITF reached a consensus that, in general, environmental contamination treatment costs should be charged to expense unless the costs are recoverable and meet one of three criteria:

1. The costs extend the life, increase the capacity, or improve the safety or efficiency of property owned by the company. For purposes of this criterion, the condition of that property after the costs are incurred must be improved as compared with the condition of that property when originally constructed or acquired, if later.

2. The costs mitigate or prevent environmental contamination that has yet to occur and that otherwise may result from future operations or activities. In addition, the costs improve the property compared with its condition when constructed or acquired, if later.

3. The costs are incurred in preparing for sale property currently held for sale.

Costs to remediate environmental contamination that do not meet one of these criteria should be expensed under the provisions of the AICPA's SOP No. 96-1, Environmental Remediation Liabilities (FASB ASC 410-30), which provides authoritative guidance on the recognition, measurement, display, and disclosure of environmental remediation liabilities. The AICPA issued SOP No. 96-1 (FASB ASC 410-30) to improve and narrow the manner in which existing authoritative accounting literature, principally SFAS No. 5, Accounting for Contingencies (FASB ASC 450-10), is applied in recognizing, measuring, and disclosing environmental liabilities.

SFAS No. 5 (FASB ASC 450-10) generally requires loss contingencies to be accrued when they are both probable and estimable. According to SOP No. 96-1 (FASB ASC 410-30), the probability criterion of SFAS No. 5 is met for environmental liabilities if both of the next conditions have occurred on or before the date the financial statements are issued:

- Litigation, a claim, or an assessment has been asserted, or is probable of being asserted.

- It is probable that the outcome of such litigation, claim, or assessment will be unfavorable.

The AICPA concluded that there is a presumption that the outcome will be unfavorable if litigation, a claim, or an assessment has been asserted, or is probable of assertion and if the entity is associated with the site. Assuming that both of the preceding conditions are met, a company would need to accrue at least the minimum amount that can reasonably be estimated as an environmental remediation liability.

Once a company has determined that it is probable that a liability has been incurred, the entity should estimate the remediation liability based on available information. In estimating its allocable share of costs, a company should include incremental direct costs of the remediation effort and postremediation monitoring costs that are expected to be incurred after the remediation is complete. An entity also should include in its estimate costs of compensation and related benefit costs for employees who are expected to devote a significant amount of their time directly to the remediation effort. The accrual of expected legal defense costs related to remediation is not required.

In cases in which joint and several liability exists and the company is one of several parties responsible for remediation, which often is the case, the entity is required to estimate the percentage of the liability that it will be allocated. The entity also must assess the likelihood that each of the other parties will pay its allocable share of the remediation liability. An entity would accrue its estimated share of amounts related to the site that will not be paid by other parties or the government.

SOP No. 96-1 (FASB ASC 410-30) provides that discounting environmental liabilities is permitted, but not required, only if the aggregate amount of the obligation and the amount and timing of the cash payments are fixed or reliably determinable. Because of the nature of the remediation process and the inherent subjectivity involved in estimating remediation liabilities, most companies will find it difficult to meet the criteria for discounting.

An asset relating to recoveries can be recognized only when realization of the claim for recovery is deemed probable. If a claim for recovery is the subject of litigation, a rebuttable presumption exists that realization of the claim is not probable. An environmental liability should be evaluated independently from any potential claim for recovery. SOP No. 96-1(FASB ASC 410-30) requires that probable recoveries be recorded at fair value. However, discounting a recovery claim is not required in determining the value of the recovery when the related liability is not discounted and the timing of the recovery is dependent on the timing of the payment of the liability.

The EITF provided examples of applying the consensus in Issue No. 90-8 (FASB ASC 410-30).

16.5 Disposals

Asset disposals may be voluntary, through retirement, sale, or trade-in, or involuntary, from fire, storm, flood, or other casualty. In general, these terms have the same meaning for accounting purposes as they do in ordinary discourse. The one exception is retirement, which for accounting purposes means the removal of an asset from service, whether the asset is removed physically or not. This is clear from Kohler's definition of retirement as “the removal of a fixed asset from service, following its sale or the end of its productive life, accompanied by the necessary adjustment of fixed asset and depreciation-reserve accounts.”

(a) Retirements, Sales, and Trade-ins

Davidson, Stickney, and Weil describe the accounting for retirements, which applies also to assets that are sold or traded in:

When an asset is retired from service, the cost of the asset and the related amount of accumulated depreciation must be removed from the books. As part of this entry, the amount received from the sale or trade-in and any difference between that amount and book value must be recorded. The difference between the proceeds received on retirement and book value is a gain (if positive) or a loss (if negative).14

As discussed next, when composite or group rate depreciation is used, no gain or loss on disposal is recognized.

When an asset is traded in, the amount that should in theory be recorded as received from the trade-in is the asset's fair market value (which is not necessarily the amount by which the cash purchase price of the replacement asset is reduced). However, in practice, a reliable market value for the old asset may not be available. In that case, the usual practice is to recognize no gain or loss on the exchange but to record as the acquisition cost of the replacement asset the net book value of the old asset plus the cash or other consideration paid.

(b) Casualties

Casualties, the accidental loss or destruction of assets, can give rise to gain or loss, even when the assets are replaced. Paragraph 2 of FASB Interpretation No. (FIN) No. 30, Accounting for Involuntary Conversions of Nonmonetary Assets to Monetary Assets (FASB ASC 605-40) makes this clear:

Involuntary conversions of nonmonetary assets to monetary assets are monetary transactions for which gain or loss shall be recognized even though an enterprise reinvests or is obligated to reinvest the monetary assets in replacement nonmonetary assets.

16.6 Asset Retirement Obligations

SFAS No. 143, Accounting for Asset Retirement Obligations (FASB ASC 410-20) was issued in June 2001. This project was undertaken by the FASB because diversity in practice had developed in accounting for the obligations associated with the retirement of long-lived assets. Some entities were accruing the obligations over the life of the related asset either as a liability or a reduction of the carrying amount of the asset while others did not recognize the liability until the asset was retired. The Statement requires that a liability be recorded for legal obligations resulting from the acquisition, construction, or development and normal operations of a long-lived asset.

(a) Initial Recognition and Measurement

If a reasonable estimate of an asset retirement obligation can be made, an entity should recognize the fair value of the liability in the period in which it is incurred. In accordance with FAS 143 par 8 (FASB ASC 410-20):

An expected present value technique will usually be the only appropriate technique with which to estimate the fair value of a liability for an asset retirement obligation. An entity, when using that technique, shall discount the expected cash flows using a credit-adjusted risk-free rate. Thus, the effect of an entity's credit standing is reflected in the discount rate rather than in the expected cash flows. Proper application of a discount rate adjustment technique entails analysis of at least two liabilities—the liability that exists in the marketplace and has an observable interest rate and the liability being measured. The appropriate rate of interest for the cash flows being measured shall be inferred from the observable rate of interest of some other liability, and to draw that inference the characteristics of the cash flows shall be similar to those of the liability being measured.

When an asset retirement obligation is initially recognized, the entity should capitalize an asset retirement cost by increasing the carrying amount of the related long-lived asset by the same amount. This cost should be charged to expense over the estimated useful life of the asset. When the asset is tested for impairment under SFAS No. 144 (FASB ASC 360-10), the asset retirement cost should be included in the carrying value tested for impairment.

(b) Subsequent Recognition and Measurement

Subsequent to initial recognition, an entity should recognize period-to-period changes in the asset retirement liability for the passage of time and revisions to either the timing or amount of the original estimate of undiscounted cash flows. Adjustments for the passage of time should use an interest method based on the credit-adjusted risk-free rate at the time of initial recognition of the liability. The adjustment should increase the amount of the liability and be charged to accretion expense. Adjustments relating to revisions in the timing or amounts of cash flows will increase or decrease the asset retirement liability and the related asset.

16.7 Depreciation

PP&E used by a business in the production of goods and services is a depreciable asset. That is, its cost is systematically amortized by charges to goods produced or to operations over the asset's estimated useful service life. That meaning is captured by International Accounting Standards (IAS) Statement No. 4, Depreciation Accounting, which defines depreciable assets as

assets that (a) are expected to be used during more than one accounting period, and (b) have a limited useful life, and (c) are held by an enterprise for use in the production or supply of goods and services, for rental to others, or for administrative purposes.

(a) Depreciation Defined

Despite its widespread use, depreciation has no single, universal definition. Economists, engineers, the courts, accountants, and others have definitions that meet their particular needs. Seldom are the definitions identical.

The generally accepted accounting definition is set forth in Accounting Terminology Bulletin No. 1 (AICPA, 1961):

Depreciation accounting is a system of accounting which aims to distribute the cost or other basic value of tangible capital assets, less salvage (if any), over the estimated useful life of the unit (which may be a group of assets) in a systematic and rational manner. It is a process of allocation, not of valuation. Depreciation for the year is the portion of the total charge under such a system that is allocated to the year.

As the definition says, depreciation accounting is “a process of allocation, not of valuation.” That is, its purpose is to allocate the net cost (cost less salvage) of an asset over time, not to state the asset at its current or long-term value.

Depreciation, as accountants use the term, applies only to buildings, machinery, and equipment. It is thus distinguished first from depletion, which is a process of allocating the cost of wasting resources, such as mineral deposits, and second from amortization, which is a process of allocating the cost of intangible assets.

(b) Basic Factors in the Computation of Depreciation

Three basic factors enter in the computation of depreciation:

16.8 Service Life

(a) Service Life as Distinguished from Physical Life

Depreciation allocates the net cost of an asset over its service life, not its physical life. The service life of an asset represents the period of usefulness to its present owner. The physical life of an asset represents its total period of usefulness, perhaps to more than one owner. For any given asset, and any given owner, physical and service life may be identical, or service life may be shorter. For example, a company that supplies automobiles to its sales force may replace its automobiles every 50,000 miles. An automobile's physical life is usually longer than 50,000 miles. But to this particular company, the service life of an automobile in its fleet is 50,000 miles, and the company's depreciation policies would allocate the net cost of its automobiles over 50,000 miles.

(b) Factors Affecting Service Life

Service life may be affected by two factors physical or functional as follows:

(i) Physical Factors

Mosich and Larsen discuss physical factors:

Physical deterioration results largely from wear and tear from use and the forces of nature. These physical forces terminate the usefulness of plant assets by rendering them incapable of performing the services for which they were intended and thus set the maximum limit on economic life.15

Wear and tear and deterioration and decay act gradually and are reasonably predictable. They are ordinarily taken into consideration in estimating service life. Damage or destruction, however, usually occurs suddenly, irregularly, infrequently, and unpredictably. Either one is ordinarily not taken into consideration in estimating service life. Its effects are therefore usually not recognized in the depreciation charge but as a charge to expense when the damage or destruction occurs.

(ii) Functional Factors

Asset inadequacy may result from business growth, requiring the company to replace existing assets with larger or more efficient assets. Or assets may become inadequate because of changes in the market, in plant location, in the nature or variety of products manufactured, or in the ownership of the business. For example, a warehouse may be in good structural condition, but if more space is needed and cannot be economically provided by adding a wing or a separate building, the warehouse has become inadequate, and its remaining service life to its present owner is ended.

Obsolescence usually arises from events that are more clearly external, such as progress, invention, technological advances, and improvements. For example, the Boeing 707 and the Douglas DC-8 jet aircraft made many propeller-driven airplanes obsolete, at least as to major airlines, because propeller-driven planes were no longer economical in long-range service, compared to more modern and efficient jets.

A distinction should be made between ordinary obsolescence and extraordinary obsolescence. Ordinary obsolescence is due to normal, reasonably predictable technical progress; extraordinary obsolescence arises from unforeseen events that result in an asset being abandoned earlier than expected. For example, computers and related software generally have a short service life span in anticipation of more advanced computers and software releases in the market within a few years.

According to the American Accounting Association (AAA) publication, A Statement of Basic Accounting Theory: “Obsolescence, to the extent it can be quantified by equipment replacement studies or similar means, should be recognized explicitly and regularly.” Thus ordinary obsolescence, like wear and tear, should be considered in estimating useful life so that it can be recognized in the annual depreciation charge. But extraordinary obsolescence, like damage or destruction, is recognized outside depreciation accounting as a charge when it occurs.

(c) Effect of Maintenance

As Welsch and Zlatkovich note, “The useful life of operational assets also is influenced by the repair and maintenance policies of the company.”16 The expected effect of a company's maintenance policy is therefore considered in estimating service lives.

(d) Statistical Methods of Estimating Service Lives

In several industries, notably utilities, estimates of service lives have been based on historical analyses of retirement rates for specific groups of assets, such as telephone or electric wire poles. These analyses have resulted in the development of statistical techniques for predicting retirement rates and service lives. Utilities have used such techniques in defending depreciation practices, replacement needs and policies, and investment valuations for rate-making purposes. Statistical techniques are appropriate for any group of homogeneous assets where estimating individual service lives is not possible or practical (e.g., mattresses and linens in a hotel, overhead and underground cables of telephone companies, and rails and ties for railroads).

Grant and Norton mention two other statistical approaches to determining service lives:

1. Actuarial methods, which aim at determining survivor curves and frequency curves for annual retirements, as well as giving estimates of average life. These methods are generally similar to the methods developed by life insurance actuaries for the study of human mortality. They require plant records in sufficient detail so that the age of each unit of plant is known at all times.

2. Turnover methods, which aim only at estimating average life. Since turnover methods require only information about additions and retirements, they require less detail in the plant records than do actuarial methods.17

(e) Service Lives of Leasehold Improvements

Leasehold improvements are depreciated over the shorter of the remaining term of the lease or the expected life of the asset. Lease renewal terms are usually not considered unless renewal is probable.

In February 2005, almost concurrent with the filing of the first wave of Sarbanes-Oxley Section 404 filings, the SEC clarified that certain accounting principles for leasehold improvements, rent holidays and landlord/tenant incentives should be followed, despite “industry practice” that had arisen where these principles were not always being adhered to. This clarification forced a spate of restatements and material weakness determinations by some larger retail establishments. The timing of this announcement made it difficult for some companies to remediate the control deficiency in time to avoid reporting a material weakness in internal controls. The letter from the SEC Chief Accountant Don Nicolaison can be found at: www.sec.gov/info/accountants/staffletters/cpcaf020705.htm.

(f) Revisions of Estimated Service Lives

Service life estimates should be reviewed periodically and revised as appropriate. The National Association of Accountants (NAA) Statement on Management Accounting Practices No. 7, Fixed Asset Accounting: The Allocation of Costs, suggests that reviews of estimates involve operations, management, engineering, and accounting personnel.

A change in the estimated useful lives of depreciable assets should be accounted for as a change in an accounting estimate. As prescribed by SFAS No. 154, Accounting Changes and Error Corrections (FASB ASC 250-10), a change in accounting estimate should be accounted for in the period of change if the change affects that period only or in the period of change and future periods if the change affects both. A change in accounting estimate should not be accounted for by restating or retrospectively adjusting amounts reported in financial statements of prior periods or by reporting pro forma amounts for prior periods.

If future periods are affected, the Opinion also requires disclosure of the effect on income from continuing operations, net income (or other appropriate captions of changes in the applicable net assets or performance indicator), and any related per-share amounts of the current period. An example of this disclosure from 2007 financial statements follows.

Change in Accounting Estimate

16.9 Depreciation Base

The cost to be depreciated, otherwise known as the depreciation base, is the total cost of an asset less its estimated net salvage value. When immaterial, net salvage value is commonly ignored.

(a) Net Salvage Value

Kohler's Dictionary for Accountants defines salvage as: “Value remaining from a fire, wreck, or other accident or from the retirement or scrapping of an asset.”18 Salvage value may be determined by reference to quoted market prices for similar items or to estimated reproduction costs, reduced by an allowance for usage. Salvage value reduced by the cost to remove the asset is net salvage value.

Net salvage value can be taken into account in either of two ways: directly, by reducing the depreciation base, or, indirectly, by adjusting the depreciation rate.

To illustrate the latter, assume an asset with a total cost of $1,000, a service life of 10 years, and an estimated net salvage value of $250. A 7.5 percent rate applied to the cost will yield the same annual depreciation charge as a 10 percent rate applied to cost less estimated net salvage value. This point should be borne in mind in interpreting stated rates of depreciation; the rates may be applied to the asset cost or to cost less net salvage value.

(b) Property Under Construction

Assets are generally not depreciated during construction, which includes any necessary pilot testing or breaking in. Such assets are not yet placed in service, and the purpose of depreciation accounting is to allocate the cost of an asset over its service life.

An exception to the general rule arises when an asset under construction is partially used in an income-producing activity. In that case, the part in use should be depreciated. An example is a building that is partially rented while still under construction.

(c) Idle and Auxiliary Equipment

NAA Statement on Management Accounting Practices No. 7 recommends that depreciation be continued on idle, reserve, or standby assets. When the period of idleness is expected to be long, the assets should be separately disclosed in the balance sheet; however, depreciation should continue.

(d) Assets to Be Disposed Of

SFAS No. 144 (FASB ASC 360-10) prohibits depreciation from being recorded during the period in which the asset is being held for disposal, even if the asset is still generating revenue.

(e) Used Assets

The depreciation base of a used asset is the same as for a new asset, that is, cost less net salvage value. The carrying value of a used asset in the accounts of the previous owner should not be carried over to the accounts of the new owner. See, however, Chapter 8 for the accounting for assets acquired in a business combination.

16.10 Depreciation Methods

Assets are depreciated by a variety of methods, including these five:

(a) Straight-Line Method

This method recognizes equal periodic depreciation charges over the service life of an asset, thereby making depreciation a function solely of time without regard to asset productivity, efficiency, or usage. The periodic depreciation charge is computed by dividing the cost of the asset, less net salvage value, by the service life expressed in months or years:

![]()

Assuming an asset cost $15,000 and has an estimated net salvage value of $750 (5 percent of cost) and a service life of 10 years, the annual depreciation charge would be $1,425, calculated as:

![]()

When the use or productivity of an asset differs significantly over its life, the straight-line method produces what some believe is a distorted allocation of costs. For example, if an asset is more productive during its early life than later, some view an equal amount of depreciation in each year as distorted. Nevertheless, the method is widely used because of its simplicity.

A survey reported by Lamden, Gerboth, and McRae showed that the straight-line method is most frequently used for financial statement purposes by companies with these five characteristics:

1. Relatively large investments in depreciable assets

2. Relatively high depreciation charges

3. Stock traded on one of the major stock exchanges or in the over-the-counter market

4. Managements with a high level of concern for (a) matching costs with revenues and (b) maintaining comparability with other firms in the industry

5. Managements with a low level of concern for conforming depreciation for financial statement to depreciation for tax purposes19

(b) Usage Methods

Two other methods, the service-hours method and the productive-output method, vary the periodic depreciation charge to recognize differences in asset use or productivity.

(i) Service-Hours Method

This method assumes that if an asset is used twice as much in period 1 as in period 2, the depreciation charge should differ accordingly. The depreciation rate is calculated as it is for the straight-line method, except that service life is expressed in terms of hours of use:

![]()

If an asset cost $15,000 and had an estimated net salvage value of $750 and an estimated service life of 38,000 hours, the calculation would be:

![]()

If the asset is used 4,000 hours in the first year, the annual depreciation charge would be $1,500 (4,000 hours × $0.375 per hour).

Welsch and Zlatkovich state, “The service hours method usually is appropriate when obsolescence is not a primary factor in depreciation and the economic service potential of the asset is used up primarily by running time.”20

(ii) Productive-Output Method

This method is essentially the same as the service-hours method, except that service life is expressed in terms of units of production rather than hours of use. If the asset just described had a service life of 95,000 units of production rather than 38,000 hours of use, the depreciation rate would be calculated as:

![]()

Depreciation by the productive-output method is illustrated by the next example from 1987 financial statements:

McDermott International, Inc.

Notes to Consolidated Financial Statements

Note 3. Change in Depreciation Method

Effective April 1, 1986, McDermott International changed the method of depreciation for major marine vessels from the straight-line method to a units-of-production method based on the utilization of each vessel. Depreciation expense calculated under the units-of-production method may be less than, equal to, or greater than depreciation expense calculated under the straight-line method in any period. McDermott International employs utilization factors as a key element in the management of marine construction operations and believes the units-of-production method, which recognizes both time and utilization factors, accomplishes a better matching of costs and revenues than the straight-line method. The cumulative effect of the change on prior years at March 31, 1986, of $25,711,000, net of income taxes of $17,362,000 ($0.70 per share), is included in the accompanying Consolidated Statement of Income (Loss) and Retained Earnings for the fiscal year ended March 31, 1987. The effect of the change on the fiscal year ended March 31, 1987, was to increase Income from Continuing Operations before Extraordinary Items and Cumulative Effect of Accounting Change and decrease Net Loss $6,556,000 ($0.18 per share). Pro forma amounts showing the effect of applying the units-of-production method of depreciation retroactively, net of related income taxes, are presented in the Consolidated Statement of Income (Loss) and Retained Earnings.

The productive-output method is sometimes used to adjust depreciation calculated by the straight-line method, when asset usage varies from normal. The adjustment may be limited to a specified range, as illustrated in this example drawn from 1986 financial statements:

Wheeling-Pittsburgh Steel Corporation

Notes to Financial Statements

Note G. Property, Plant, and Equipment

The Corporation utilizes the modified units-of-production method of depreciation which recognizes that the depreciation of steelmaking machinery is related to the physical wear of the equipment as well as a time factor. The modified units-of-production method provides for straight-line depreciation charges modified (adjusted) by the level of production activity. On an annual basis, adjustments may not exceed a range of 60% (minimum) to 110% (maximum) of related straight-line depreciation. The adjustments are based on the ratio of actual production to a predetermined norm. Eighty-five percent of capacity is considered the norm for the Corporation's primary steelmaking facilities; 80% of capacity is considered the norm for finishing facilities. No adjustment is made when the production level is equal to norm. In 1986 depreciation under the modified units of production method exceeded straight-line depreciation by $1.5 million or 3.2%. For 1985 and 1984 aggregate straight-line depreciation exceeded that recorded under the modified units-of-production method by $10.1 million or 18.3%, $7.0 million or 12.6%, respectively.

The productive-output method recognizes that not all hours of use are equally productive. Therefore, the theory underlying the preference for a usage method would point to the productive-output method as the better of the two.

(c) Decreasing-Charge Methods

Decreasing-charge methods allocate a higher depreciation charge to the early years of an asset's service life. These methods are justified on the next grounds:

- Most equipment is more efficient (hence more productive) in its early life. Therefore, the early years of service life should bear more of the asset's cost.

- Repairs and maintenance charges generally increase as an asset gets older. Therefore, depreciation charges should decrease as the asset gets older so as to produce a more stable total charge (repairs and maintenance plus depreciation) for the use of the asset during its service life.

(i) Sum-of-Digits Method

This method applies a decreasing rate to a constant depreciation base (cost less net salvage value). The rate is a fraction. The denominator is the sum of the digits representing periods (years or months) of asset life. The numerator, which changes each period, is the digit assigned to the particular period. Digits are assigned in reverse order. For example, if an asset has an estimated service life of five years, the denominator would be 15, calculated as:

![]()

In the first year the rate fraction would be 5/15, in the second year 4/15, in the third year 3/15, and so on. The denominator may be calculated by means of the next formula, where n is the service life in years or months:

![]()

For example, if the service life is estimated to be 25 years:

![]()

(ii) Fixed-Percentage-of-Declining-Balance Method

This method produces results similar to the sum-of-digits method. However, whereas the sum-of-digits method multiplies a declining rate times a fixed balance, the fixed-percentage-of-declining-balance method multiplies a fixed rate times a declining balance. The rate is calculated by means of the next formula, where n equals the service life in years:

![]()

The rate thus determined is then applied to the cost of the asset, without regard to salvage value, reduced by depreciation previously recognized. The result is to reduce the cost of the asset to its estimated net salvage value at the end of the asset's service life. (Some salvage value must be assigned to the asset, since it is not possible to reduce an amount to zero by applying a constant rate to a successively smaller remainder. In the absence of an expected salvage value, a nominal value of $1 can be assumed.)

To illustrate, assume an asset with a cost of $10,000, an estimated salvage value of $1,296, and an estimated service life of four years:

The first year's depreciation will be $4,000 ($10,000 × 40%), the second year's $2,400 [($10,000 – $4,000) × 40%], and so on, leaving at the end of the fourth year a net asset of $1,296.

(iii) Double-Declining-Balance Method

The double-declining-balance method was introduced into the income tax laws in 1954. Since then, it has gained increased acceptability for financial reporting as well. This method differs from the fixed-percentage-of-declining-balance method by specifying that the fixed rate should be twice the straight-line rate. Otherwise the two methods are identical: The fixed rate is applied to the undepreciated book value of the asset—a declining balance.

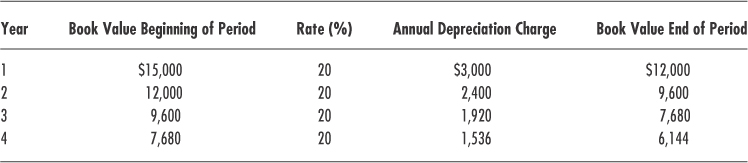

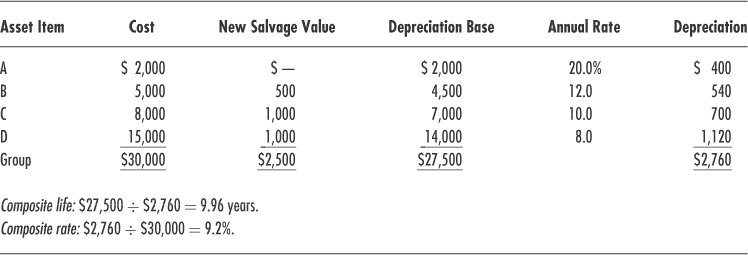

To illustrate, assume an asset with a cost of $15,000, an estimated net salvage value of $750, and an estimated service life of 10 years. Twice the straight-line rate would be 20 percent. Exhibit 16.1 shows the calculation for the first four years.

Exhibit 16.1 Depreciation Using the Double-Declining-Balance Method

Note that, as with the fixed-percentage-of-declining-balance method, the rate is applied to the cost of the asset without regard to net salvage value. This means that by the end of the asset's estimated service life, some amount of undepreciated book value will be left in the asset account. But since the depreciation rate is determined without regard to estimated net salvage value, the undepreciated amount left in the account will likely differ from net salvage value. For example, at the end of the 10-year service life of the asset illustrated in Exhibit 16.2, the asset's book value would be $1,611, which is $861 greater than estimated net salvage value. To avoid such differences, companies usually switch from the double-declining-balance method to the straight-line method sometime during an asset's service life.

Exhibit 16.2 Comparison of Annual Depreciation Charges: Straight-Line, Sum-of-Digits, and Declining-Balance with Switch to Straight Line

To calculate the straight-line depreciation charge at the time of the switch, the net book value (cost less accumulated depreciation), less estimated net salvage value, is divided by the estimated remaining service life. For example, if an asset has a remaining depreciation base (cost less estimated net salvage value) of $4,620 and seven years of remaining service life, a straight-line charge of $660 for the next seven years will depreciate the asset to its net salvage value.

The optimal time to make a switch is when the year's depreciation computed using the straight-line method exceeds depreciation computed using the double-declining-balance method. That is usually sometime after the midpoint of the asset's life.

Exhibit 16.2 compares the annual depreciation charges computed by the straight-line method, the sum-of-digits method, and the double-declining-balance method with switch to straight-line.

Note that although all three methods charge the same total amount to expense over the same service life, the amounts charged at the midpoint of the asset's service life differ:

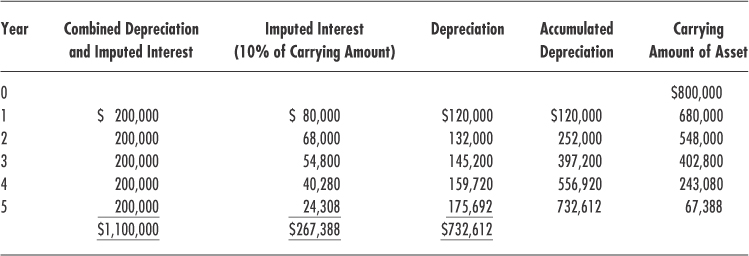

(d) Interest Methods

Two methods, the annuity method and the sinking-fund method, compute depreciation using compound interest factors. Both methods produce an increasing annual depreciation charge. Neither method is used much in practice.

(i) Annuity Method