For a variety of motivational and tax purposes, firms do not rely exclusively on cash payments to compensate employees for services rendered. The three primary types of “deferred benefits” that firms give to employees are pension payments, health care benefits, and stock options. These are essentially delayed compensation.

Let us begin with pension and health care costs. Today, most pension and health care costs are defined contribution plans. This means the firm agrees to make a set contribution. For pension costs, firms pay a fixed amount usually based on the employee’s salary (the fixed contribution made by the firm can come with or without a cap or maximum and is often matched to contributions made by the employee). The pension becomes the property (“vests”) of the employee immediately.1 The amount the employee will receive at retirement is based on the actual contributions to and returns of the plan, and the firm has no additional liability once it makes its contractual payments. Similarly, most health care plans today are also defined contributions, with firms making a set payment toward an annual health care plan (and with the employee often sharing the costs and perhaps paying set amounts each time they see a health care professional or obtain medicine). The accounting for the firms’ defined contribution plans is straightforward: The required annual contribution is the annual expense, with any unpaid amount at the end of the year recorded as a liability.

By contrast, defined benefit plans stipulate future benefits, often for the life of the employee (and sometimes the lives of the employee’s dependents as well). Defined benefit plans were once ubiquitous in large corporations but today are primarily found in firms with unions, governmental organizations, or remain as a legacy in firms that once had them but shifted to defined contribution plans. For example, General Motors Company has a defined benefit plan for those employees who were hired before January 2001.2 Defined benefit plans are perhaps the most opaque part of financial statements because they include, by necessity, a myriad of future estimates, which, by definition, are likely to be wildly inaccurate and susceptible to manipulation by management.

What Amounts are on the Balance Sheet, and How are they Computed?

A defined benefit is a contractual agreement setting out the amount the employee will get in cash or benefits in the future, usually after retiring from the firm. For pensions, the amount is usually based on a percentage of the employee’s salary during his or her last year working for the firm, or based on an average of the last few years. For example, a plan may stipulate that any employee who works for the firm for 25 years or more will receive 70 percent of their last year’s salary upon retirement until death.3 Furthermore, the amount paid is often increased for inflation, with inflation usually calculated based on some government index like the consumer price index. Health care plans usually stipulate what part of health expenses will be covered (e.g., 100 percent, 90 percent, with certain copayments). Firms are expected to make annual payments into a separate outside fund that will then be used in the future to pay the employees’ pensions and health care costs. Thus, the firm has both an asset for the defined benefit (e.g., the pension fund) and a liability for the defined benefit obligation.

The firm must estimate the future cash benefits that will be paid to employees and then discount them to compute the net present value (NPV) of the liability. This is then compared to the value of the plan assets (funds paid in the past plus investment income less amounts paid). Although the net amount can be an asset or liability (or close to zero if the firm accurately sets aside the amount required to pay out), for most firms it is a liability because most firms do not set aside more than they believe they will have to pay. The good news is that an actuary does all the estimates and calculations.4 The bad news is there are numerous estimates and assumptions that make the estimated amount highly suspect.

What is Disclosed?

Corporate accounting rules for defined benefit pensions and other postretirement plans now mandate that public companies must recognize the net position (overfunded or underfunded) in their balance sheets.5 This is a major improvement over the prior limited footnote disclosure, which was itself a huge improvement from the prior pay-as-you-go system where only the actual current year payment was recorded as an expense. One could (and some do) argue that firms should present both the pension fund asset and liability separately and not as one net amount. However, this is only a minor issue because users of financial statements can easily adjust the Balance Sheet using the information in the Notes (e.g., remove the net amount and set up a long-term asset and long-term liability as per the amounts listed in the footnote).

What is included in the asset (pension fund) and pension benefit obligation (PBO)? The asset includes the opening balance plus contributions made during the year plus any gains or losses on the investments in the plan less the benefits paid during the year (plus or minus some additional adjustments). The PBO is essentially the NPV of estimated vested and nonvested (amounts that belong or do not yet belong to the employee) benefits based on the expected salary levels at retirement. This means that if the plan provides for an employee to be paid 70 percent of their last year’s salary, the estimate must be based on what the employee is expected to be making at the time of retirement. In addition, the PBO liability includes an estimate for all employees, not just those who have already reached the required years of service (e.g., 25 years).6

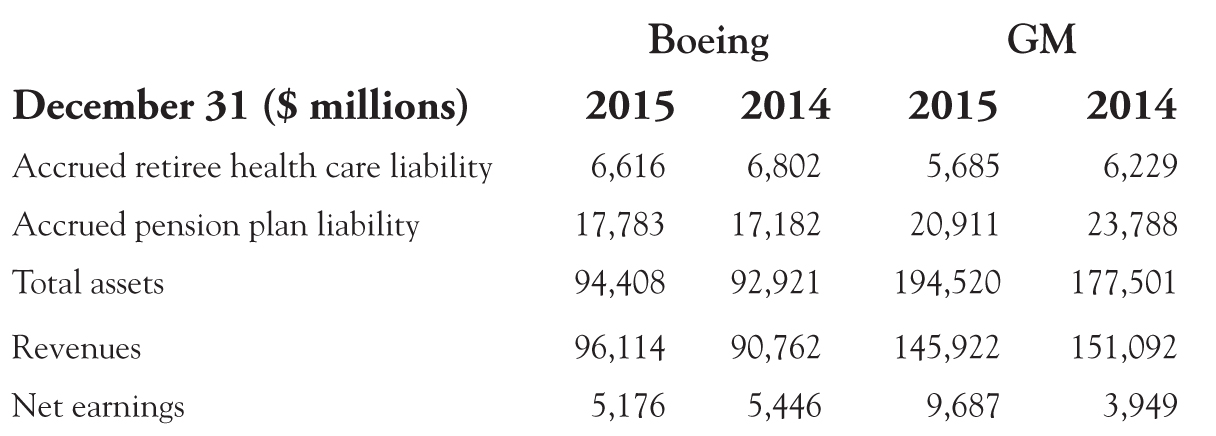

In their 2015 year-end financial statements, Boeing Corporation (Boeing) and General Motors Corporation (GM) showed the following (the first two items are deferred benefits, while the last three are presented for comparison purposes):

To illustrate the complexity of the accounting for pensions, the section of the Notes to the Financial Statements discussing pensions (excluding any management discussion prior to the financial statements) is nine pages long for Boeing (Note 14, pages 87 to 95) and seven pages for GM (Note 13, pages 77 to 83).

What Is Required to Compute Deferred Benefits’ Net Value?

First, the amount of future payments must be estimated. For this computation, the actuary begins with the number of employees who have retired and those who have reached the required years of service level. For those employees who have already retired, the actuary will compute their expected life. This is done using life tables similar to life insurance calculations. It is based on the employee’s age, gender, health habits (e.g., smoker versus nonsmoker), and so on. For those employees who have not yet retired, the actuary must first estimate when they are likely to retire and then their expected life after retirement. This provides the actuary with the number and timing of future payments. As noted above, this is almost certainly a low estimate because, for those employees not yet retired, the calculation uses their current salary to compute the annual payment rather than what the firm is actually likely to pay. These estimated future payments are then discounted at a “reasonable” discount rate.

What is a reasonable rate? It is the rate on a “high quality,” fixed income security (which would mean a low-risk security rated BBB or better7). Boeing used 4.20 percent in 2015, while GM used 4.06 percent. As a comparison, the rate for the 30-year U.S. Treasury Bond was 3.01 percent on December 31, 2015. Thus, Boeing and GM are using rates slightly higher than what is considered a long-term, risk-free rate. All seem “reasonable” to your author, and certainly all represent the rate of high quality, fixed income securities at the end of 2015. However, remember that the higher the rate, the lower the present value of the future liability. Thus, by using a higher estimated rate, a firm will lower the estimated liability.

The steps above provide the NPV of the future liability (i.e., the PBO). However, the firm will also have made, and be expected to continue making, periodic payments to a plan to fund the future cash outflows. These payments will be invested in various securities, so estimates of expected returns on those investments are also required. These expected returns will reduce the annual expense as explained below.

How much should the firm pay into the fund each year? In theory, it should be enough to offset the future liability. However, firms are only required to fund the amount based on the employees working in the current year (e.g., the service cost, as discussed below).

How much will the fund earn on its investment each year? This depends on how the fund is managed. Unless the firms invest solely in government bonds, it is reasonable to expect these payments to earn more than the long-term, risk-free rate (i.e., the rate offered by the U.S. government); however, there is also a risk the firm could lose money. How much do firms estimate they will earn? At the end of 2015, Boeing estimated its pension plan would earn 7.0 percent per year, GM estimated its plan would earn 6.38 percent.

Thus Boeing uses a higher estimate of what its pension plan will earn (creating a lower expense) and a higher discount rate for its obligation (creating a lower liability) than GM. If GM’s estimates are “reasonable,” then Boeing appears optimistic (and given current market yields one could argue even GM’s 6.38 percent estimated plan earnings seem optimistic). Note that the employer usually owns the assets in the plan and bears the risk (or reward) of the plan not having enough (or having any excess) to make the future cash payments.8

The Annual Deferred Benefit Expense

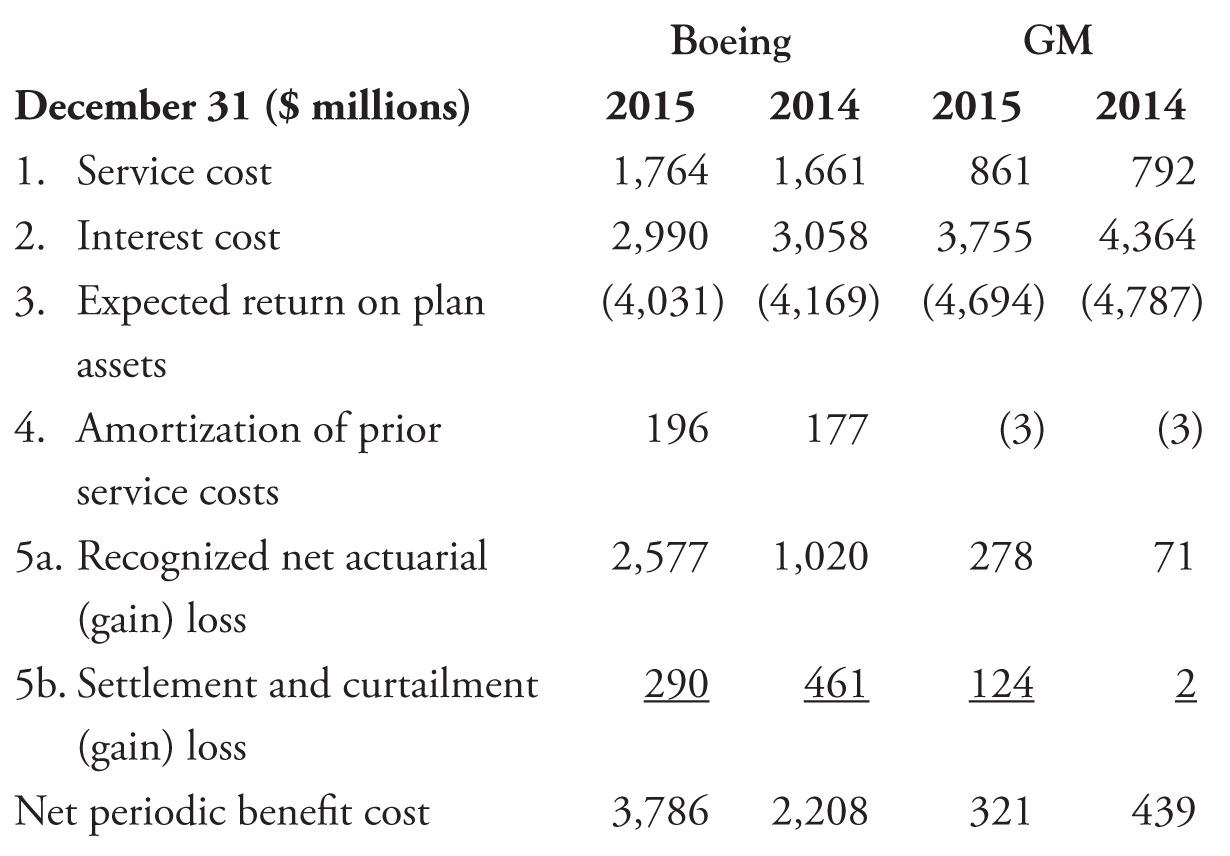

The amount a firm can deduct on its tax return for deferred benefits is the actual contribution. The firm’s accounting expense for deferred benefits, the reduction to profit on the income statement, is not the actual contribution.9 The pension expense is the net of five factors:

1. + Service cost

2. + Interest on the projected benefit obligation

3. – Expected return on pension plan (fund) assets

4. + Amortization of prior service cost

5. +/– Effects of gains or losses

Each of these five components will be discussed below and are disclosed with details in the Notes to the Financial Statements.

1. The service cost is the NPV of the actuarial estimate of the cost of future benefits which will be provided to employees arising from work done by employees during the current year. This amount is also the government-imposed minimum required contribution by the firm.

2. The interest on the projected benefit obligation is the increase in the obligation (e.g., the PBO) due to the passage of time. It can be thought of as the opening balance of the obligation at the start of the year times an interest rate.

3. The expected return on the pension fund is the asset value at the start of the year times the expected long-term rate of return. Note that this is not the actual return but rather an average expected in the long run that is based on the firm’s estimated long-term rate of return (as mentioned above, the expected return on the pension fund is 7.0 percent for Boeing, and 6.38 percent for GM).

4. Prior service costs arise from the increase in the pension plan obligation due to the adoption of a plan or amendments to it (the entire cost increases the pension benefit obligation with an offsetting decrease in other comprehensive income10). These costs are amortized over the expected service lives of the employees (by increasing the pension expense and decreasing the accumulated other comprehensive income).

5. Gains and losses are the difference between the expected and actual returns (fair market values). The gains and losses are not fully recognized in the Income Statement in the year they occur. Rather, they are included “in a rational and systematic method over five years or less.”

The amounts for Boing and GM are as follows:

Another way to think about defined benefit plans is as follows:

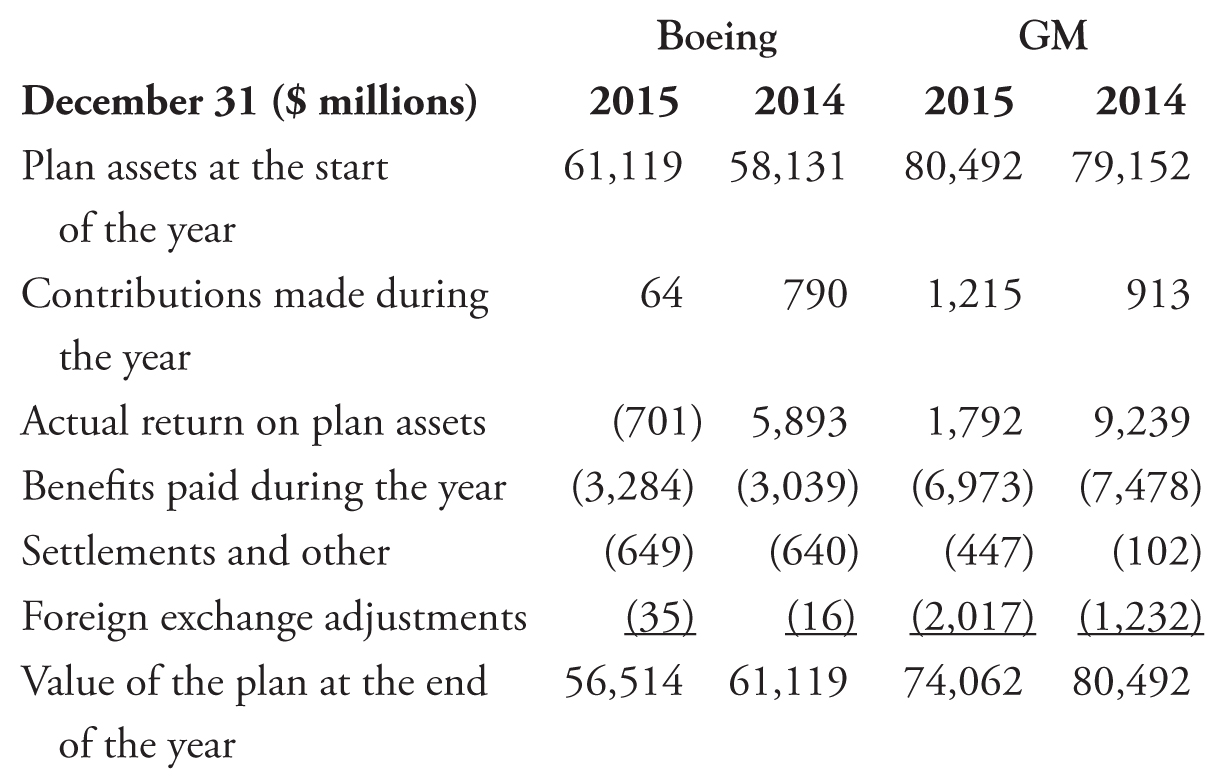

The asset side (i.e., the value of the plan) is the pension plan’s value at the start of the year and is increased by payments into the plan plus (or minus) any gains (or losses) from investments minus benefits paid. There are also additional adjustments for changes in the plan and foreign currency.

To illustrate, the assets for Boeing and GM are as follows:

The liability side starts with the prior year-end obligation and is increased by the service cost (the NPV of the current year’s obligation) and an interest charge (reflecting the increase in the obligation over time). Next, the obligation is reduced by the actual benefits paid during the year. The complicated calculation is the actuarial gains or losses, which reflect changes in the plan and in previous actuarial estimates.

To illustrate, the liabilities for Boeing and GM are as follows:

If the plan assets are greater than the PBO, then the firm shows a net asset. Otherwise, as is more common, if the plan assets are less than the PBO then the firm shows a net liability.

Both Boeing and GM have net liabilities as follows:

Reconciliation of Balance Sheet and Income Statement

As can be seen from the numbers above, the change in net liability is not simply the opening balance plus the increase from the current year’s benefits less the benefits paid during the year. First, while the expense is a calculation trying to match this year’s cost (i.e., the benefits accrued during the current year) to this year’s revenues, it has additional complications. Second, the change in net liability reflects other adjustments as well, including all unrecorded past service costs (of which the expense includes only a portion to limit the impact or, smooth, earnings).

There is also an additional amount for the actuarial change (i.e., the change due to changes in actuarial estimates), of which only a portion is amortized into the annual expense (as noted above, each year’s adjustment is included in expenses over five years). Where is the rest of the actuarial change? In the owners’ equity account called accumulated other comprehensive income that bypasses the Income Statement (i.e., 1/5th of the adjustment goes into the current year’s expense and 4/5th goes into owners’ equity and is then slowly included into future year’s expenses).

Why not include all the gain or loss in the current year’s expense and Income Statement? It is similar to the treatment of short-term, marketable securities classified as “available for sale” where gains and losses are recorded in owners’ equity as accumulated other comprehensive income and do not impact the Income Statement until realized. In a related fashion, the potentially large swings in the actuarial revaluations as well as the gains and losses on investments are also recorded in owners’ equity under the title accumulated other comprehensive income. Then, each year a portion of the total is amortized into the current year’s expenses and thereby flows through the Income Statement.

Essentially, rather than record the full impact of the amount in one year, and have a potentially material impact on net income, the impact is smoothed over time. Why? Basically because management wants to smooth earnings.

For example, imagine a new plan is started at the end of 2016. The plan provides benefits after 25 years of service, but not from the date the plan started, rather from the date the employees started work. This means the firm will have two types of expenses in the current year: The first is the discounted present value of future pension payments resulting from all employees under the plan due to the current additional year (of service). The second (the actuarial adjustment) is the discounted future liability based on the employees’ service from the adoption of the plan (for prior years of service) or amendments to it. The former (the service cost) is fully included in the current year’s expense. The latter (the actuarial adjustment) is initially set up as an obligation (liability—the pension benefit obligation) and in owners’ equity (the accumulated other comprehensive income). The amount in owners’ equity (accumulated other comprehensive income) related to the adoption of the plan (the prior service costs) is amortized based on years of service using a straight-line or accelerated method. Amortization on any actuarial gains and losses (on the pension assets or obligation) is only required if the amount exceeds the greater of 10 percent of the value of the plan assets at the start of the year or 10 percent of the PBO at the start of the year. The process for amortization can be quite complex.

What should an outside analyst trying to understand the impact of deferred benefits look for? He or she should look at the estimated returns to the plans and discount rates and see how they compare to reality and other firms. In addition, how much of the plan’s prior gains and losses has been amortized (included) should be examined. The analyst may also decide to set up the asset and liability separately instead of having the single net amount shown by the firm. Finally, the analyst may decide to include the full amount shown in the Notes to the Financial Statements (including nonvested) or even to hire an actuary and try to estimate for himself the actual total owed using estimated future salary levels.

Stock Options

Another way to reward employees, particularly executives, is to grant them stock options. A stock option gives the employee the right to buy the firm’s stock at some point in the future for a set price. For example, in addition to an annual salary, assume a firm gives an employee the option to purchase 1,000 shares of the firm’s stock in one year’s time for $70 per share. The employee will exercise her right to buy the 1,000 shares directly from the firm for $70,000 if the shares are trading for more than $70. The employee is rewarded by the difference between the exercise price of the option (i.e., the contractual purchase price, in this case $70) and the market price of the share. The employee, if she chooses, can then turn around and sell the shares for the market price above $70, which leaves her with gains on each share sold.

Employee stock options are usually issued with some restrictions. Common restrictions are that the employee:

• Loses the options if they leave the firm,

• Is not allowed to sell the options to others,

• Cannot hedge the options (i.e., engage in any transaction to lock in a future price to sell the shares), and

• Cannot sell the shares until a specified date.

Why would a firm issue stock options to employees? One reason has to do with trying to better align employee incentives with those of the owners. Paying a bonus based on accounting profits was thought to provide an incentive for employees to engage in efforts to increase short-term profits (through both economic and accounting choices). In contrast, stock options were thought to provide an incentive to increase the stock price, hopefully through economic actions to improve a firm’s cash flows.

Another reason was the accounting treatment of stock options. Prior to 1994, stock options given to employees were not accounted for as compensation. From 1994 through 2004, firms were encouraged to include stock options as compensation but only required to do so if the options were “in-the-money.”11 Prior to 2005, firms could issue stock options without an Income Statement impact, other than potentially diluting earnings per share (earnings per share are discussed in the next chapter). Thus, there was only an accounting event when the stock option was exercised, and then it was purely a Balance Sheet event. Using the example above, assume the employee exercised her option to purchase 1,000 shares at $70 per share when the stock was trading at $90 per share. The accounting entry would increase cash and common stock by $70,000.

The employee received a $20,000 benefit (1,000 × $90 – 1,000 × $70), which caused a dilution in value to owners but was not recorded in the financial statements.12 In contrast, if the employee was paid a cash bonus of $20,000, the entry would increase wage expense (which would ultimately reduce retained earnings) and reduce cash by $20,000.

Note that in the first case, the firm records the stock issue at $70,000 and ignores the fact that it could have sold the stock in the open market for $90,000 and effectively gave the employee compensation of $20,000. The entry would have no Income Statement effect. In the second case, the firm pays out $20,000 in cash which reduced profits and retained earnings.

In 2005 and beyond, the value of the stock option at the date it was given has to be included as compensation.13 This means that a firm has to value the stock options (as opposed to the value of the underlying stock) when first given to employees. Assuming the above stock options were worth $15,000 when issued, the entry would (there are some additional possible complications) increase wage expense (and ultimately reduce retained earnings) and increase an owner’s equity account called stock options by $15,000.

U.S. accounting rules do not specify a particular valuation method to determine fair value. The choice is based on the terms, or “substantive characteristics,” of the options being valued and established principles of financial economic theory. Essentially, if similar options are traded in the market, then the market price can be used. Otherwise, some formula like the Black–Scholes–Merton formula is used.14 Also, the expense has to be tied to the terms of the option. As with the actuarial valuation for pensions, the “fair value” of options using a finance formula is less than objective and of uncertain merit.

An exception, where fair values are not determined and there is no wage expense, to the above example is if an employee stock purchase plan is deemed not to have a compensation effect. This occurs if the plan has all of the following characteristics:

• The terms of the plan are not more favorable than an offer to shareholders,

• The price discount between the market price of a share and the price the employee can purchase the share at is 5 percent or less, and

• The offer must be made to most employees with equivalent participation.

Furthermore, the option features are limited to:

• A short time period of less than 31 days after price set to enroll,

• The price is based solely on the market price at the date of purchase, and

• The employee cannot opt out and get a refund of amounts already paid.

The Debate over Expensing Stock Options

It may seem intuitive to the reader that stock options represent compensation and should therefore be included as wage expense when given. However, the accounting treatment of stock options was, in fact, highly contentious, and the rules were only enacted when the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) forced them on the profession (and, as noted, this occurred only in 2005).

The arguments against expensing stock options include:

1. Employee options dilute existing stockholders’ equity, and therefore they are not an expense,

2. Models to measure options are inaccurate, unreliable, and therefore misleading,

3. Giving companies a choice of which model and assumptions to use will result in a range of values and, therefore, earnings charges, and

4. Expensing stock options distorts performance because it is a noncash charge.

Or perhaps, as one article argued:

“Mandating the expensing of employee stock options is one of the most radical changes in accounting rules in history, and we believe the Financial Accounting Standards Board (FASB) and the SEC have made a mistake.”15

The counter arguments are:

1. Providing options to employees is a form of compensation and therefore an expense,

2. The Notes to the Financial Statements can provide information, as with actuarial valuations for pensions, on the accuracy and reliability of the models,

3. There are numerous choices in models and assumptions throughout accounting resulting in a range of values and, therefore, earnings charges, and

4. Not expensing stock options distorts performances because it fails to properly match the treatment of stock options to cash compensation.

Or, as one article noted:

“Despite the pronouncements of a few renegades in our disciplines, we believe that there is near unanimity of opinion among scholars in the field of accounting and finance that the value of employee stock options should be expensed on a firm’s income statement at the time they are granted.”16

The impact of expensing the value of stock options can be substantial. Imagine you have two firms. The first pays an employee $100,000. The second pays an employee $85,000 and gives the employee stock options worth $25,000. The net compensation to the employee in the second firm is higher than the first, yet all else equal without recording the stock option, the second firm will show higher profits than the first.

Standard & Poor’s estimated the new accounting rules would have reduced reported 2004 earnings among the S&P 500 by 7.4 percent. In an August 2, 2004, press release, Intel reported that its second-quarter 2004 profit would have decreased 17 percent if it had expensed its stock options.

Have the new accounting rules requiring firms to include stock options as compensation changed the number of firms giving employees stock options? Initially surveys indicated firms were planning to scale back. “Of the companies responding to the survey, 31 percent indicated that stock options will remain their primary, long-term incentive vehicle after their decision to expense stock options, while 56 percent replied that stock options will no longer be their primary long-term incentive vehicle; 13 percent were undecided.”17 However, more recent research is less clear. Firms may have scaled back a bit, but stock options are still prevalent as a form of compensation.

The Bottom Line

Although the accounting for a firm’s defined contribution plans is straightforward, the accounting for defined benefit plans (which are less common today) requires a myriad of future estimates, which, by definition, are likely to be wildly inaccurate and susceptible to manipulation by management. In addition, the accounting for stock options today corrects for many of its prior deficiencies but still needs to be evaluated by the analyst.

The next chapter provides a brief exploration of a few more advanced topics (i.e., earnings per share, foreign currency, comprehensive income, fair value accounting, and how to adjust from first-in-first-out [FIFO] to last-in-first-out [LIFO]).

_________________

1There are numerous variants of these plans, and some firms only start the plans after an employee has worked for the firm for a number of months or years. Most plans are driven by a formula which takes the following general form: Annual Retirement Benefit = projected salary at retirement × years of service × percentage multiplier (the years of service × percentage multiplier provide the percentage of the projected salary which will be paid out).

2GM’s defined benefit plan is even more complicated as it was “frozen” as of September 2012 due to GM’s bankruptcy. This means even for those employees who were hired before January 2001 and are still working at GM, only their work through September 2012 counts toward their defined benefit plans. However, the GM example shows how major firms, even with strong unions, have been phasing out their defined benefit plans. Today, the only major group of employees able to get defined benefit plans are those working for the government—and the liability for these future payments is a major issue both as a ticking budgetary time bomb and as an accounting problem.

3Often there is a sliding scale whereby the longer the employee works, the higher the retirement payoffs (e.g., 70 percent after 30 years, 75 percent after 35 years, and 80 percent after 40 years or more).

4An actuary is a mathematician trained in risk and life expectancy calculations.

5In the United States, this became effective on December 2006.

6One can see that firms with these plans have an incentive to fire employees shortly before they reach the required service level to avoid having to pay future benefits—a topic beyond the scope of this book.

7Bond ratings are meant to measure the risk associated with investing in a particular bond. There are three major rating agencies: Standard and Poor’s, Moody’s, and Fitch. Each has a slightly different rating mechanism, but for all three the safest rating is AAA, followed by AA+ through D, with D meaning the firm is in default or not currently paying its interest and principal as per its debt contract(s). BBB and above is considered an investment-grade rating meaning the firm is thought to have adequate funds to meet its bond repayment requirements. BB and below is considered high-yield or junk status indicating an increased risk of non-payment.

8Corporate raiders, those “nefarious” individuals who buy up all the shares of a firm at a premium and then engage in various activities to enhance the firm’s cash flows, have often used the acquired firm’s pension plan to help pay for the acquisition.

9The actual contribution can often be found in the cash flow statement, otherwise it can be found in the Notes to the Financial Statements.

10A more detailed discussion of comprehensive income is provided in the next chapter.

11A stock option is out-of-the-money if the exercise price is above the current market price at the time the stock is issued (e.g., building upon the example above, the stock price when the options were granted would have to be below $70). By contrast, if the stock option is in-the-money at the time of issue (e.g., in the same example above, the stock price when the options were granted would have to be above $70), then the difference between the stock price and exercise price must be recorded. Most employee stock options are issued at-the-money, where the exercise price equals the current market price on the date the options are granted (e.g., in the example above, the stock price when the options were granted would be $70). In this latter example, the employee benefits if the stock price rises between the date the options are granted and the date they can be exercised.

12Imagine a firm could be sold for $90 million cash and has 1 million shares issued and outstanding, with each share being valued at $90 per share ($90 million/1 million). All else equal, if the firm then issues 1,000 shares for $70,000, the firm is now worth $90,070,000 and has 1,001,000 shares issued and outstanding, with each share now worth $89.98. This is a dilution of $0.02 cents per share due to the new share issue. Footnote disclosure is required of any stock options.

13Year-end June 15, 2005 for public firms and December 15 for nonpublic firms. However, many firms started to voluntarily include stock options as compensation in 2001 after the Enron scandal due to increased investor scrutiny.

14A discussion of the Black–Scholes–Merton model is beyond the scope of this text. It is available in most introductory finance textbooks.

15The comment was made by Kip Hagopian, a veteran venture capitalist and principal author of the position paper, “Expensing Employee Stock Options is Improper Accounting,” California Management Review, Summer 2006.

16See: Zvi Bodie, Robert Kaplan, and Robert Merton (August 12, 2002). “Stock Options: To Expense or Not to Expense,” Wall Street Journal. While your author does completely agree with the argument that stock options should be expensed, he also notes the quote is based on a belief not substantiated by empirical evidence.

17See: J. Gregory Kunkel and Richard T. Lau (January, 2005). “Early Adopters Plan for Changes,” CPA Journal.