Long-Term Investments and Consolidated Statements

This chapter examines what is perhaps the most interesting, and for many the most difficult, element of accounting; the long-term intercorporate investments made by one firm in another for strategic, long-term purposes, and in particular, consolidations. It will explain what the accounting terms “goodwill” and “noncontrolling interest” (also called “minority interest”) actually mean and how they are computed. Consolidation is an advanced accounting topic. It is often covered in the third course offered to those going into the accounting profession and may encompass more than half the course. The presentation here is a simplified version of what is actually done.

Long-Term Intercorporate Investments1

Why would a firm buy another firm’s shares? The objective is, as with any investment, to obtain returns above its cost of capital. If the expected cash flows discounted at the appropriate discount rate provide a positive net present value2 (NPV), then an investment provides more than competitive returns. If the investment is for long-term strategic purposes, with no intention of selling it in the coming year, it is classified as a long-term asset.

If a firm does buy another for long-term strategic purposes, why buy shares? Why not simply buy the business itself (the assets and liabilities)? There are many reasons. First, buying shares may limit liability. Normally, the most a shareholder of a firm (whether that shareholder is an individual or another firm) can lose is the amount invested. Imagine you buy shares of a pharmaceutical firm that sells a medication that turns out to have a harmful side effect, is sued, and is ordered to pay more than the value of its assets. The pharmaceutical firm will go bankrupt, and the shareholders will lose their investment. Normally, the shareholders are not liable for damages beyond the value of the firm itself. The court does not pierce the “corporate veil” to demand that the assets of the individual investors be used to complete the payment required by the lawsuit. This is a key benefit of the corporate form: owners can shield their personal assets. By contrast, in most partnerships, the partners (or at least certain key partners) have unlimited liability, which means their personal assets are at risk.3 Many people argue that the seeds of the financial crisis of 2008 were set when investment banks stopped being partnerships and became corporations. As partnerships, the investment banks’ senior managers were partners and were much more cautious about the investments they made. As corporations, the investment bank managers were more willing to bet the firm. If the bet won, the managers would each receive a portion of a potentially enormous gain. If the bet lost, the managers simply had to find another job.

Another advantage of purchasing shares in an intercorporate investment is the ease of selling and buying. Transferring all the assets of one firm to another may be more difficult for several reasons. First, assets often cannot be sold without agreement of lenders. Second, it may be difficult to transfer the business itself (e.g., the organizational form, the human capital, the distribution networks). Imagine an individual has an employment contract with Firm A, which sells all its assets to Firm B. Can Firm A sell the employment contract when it sells its assets to Firm B? The answer, other than for certain sports franchises, is normally no. By contrast, when a firm’s shares are purchased, the sale includes all the assets and liabilities of the business, including the corporate structure, employment contracts, and so on. Finally, the details of the sale—what is included in the sale and what is not—are much simpler when purchasing shares than when detailing specific assets and liabilities.

There are also corporate tax reasons which make purchasing shares a preferred method for intercorporate investments. Many multinational firms today have multiple operating firms (sometimes more than one in each country where they have operations). These multinational firms often set up a subsidiary, which owns and controls the multinational firm’s intellectual capital (e.g., patents and copyrights), in a country with low income taxes (e.g., Ireland).4 All the operating firms pay a royalty fee to the intellectual capital subsidiary, thereby lowering the taxable profits in high-tax countries and creating profits in the low-tax country.

In addition, certain countries limit foreign ownership, forcing firms to create local subsidiaries in these countries where the parent firm’s ownership is below the legally set percentage (e.g., 50 percent).

Creating a new separate entity may also be an easier way for a firm to expand and diversify with few of its own investment funds, as once created it can then sell additional shares of the new entity to others. For example, Disney set up Disneyland Paris without investing very much of its own funds by selling shares of Disneyland Paris to others. Disney’s profit from the venture came primarily from licensing fees. Likewise, when the Coca-Cola Company was establishing itself across the United States and then the world, it created separate bottlers to package and sell its product. Coca-Cola may have kept a percentage of the ownership in each bottler, but it was able to expand much more rapidly by allowing others to buy a majority stake and run these enterprises.5

Clearly, there are many reasons for intercorporate investments.

Accounting for Long-Term Intercorporate Investments

The accounting for long-term intercorporate investments is based upon the investing firm’s ability to extract profits from the subsidiary. The ability to extract profits is broken into three categories: minority passive, minority active, and majority. Depending on the category, the parent firm will use the cost method or equity method in accounting for its investment in the subsidiary firm and present the investment as a line item or “consolidate” all the subsidiaries’ accounts with the parent companies’ accounts. Let us examine each of the three types of situations and then the related accounting treatment.

Minority passive occurs when the investing firm owns less than 50 percent of the voting shares of the subsidiary (i.e., is a minority owner) and has no influence (i.e., is passive) regarding if or when the subsidiary pays dividends. In the case of minority passive, accounting for the investment is done using the cost method. One situation in which this minority passive status occurs is when another firm (or a group of investors acting together) owns a majority stake in the subsidiary. This means that the investing firm necessarily has no influence on dividends because the majority group has control (with more than 50 percent of the votes). However, if no other firm or group has a majority stake, the question regarding whether or not the investing firm has a minority passive situation becomes one of influence: Does the investing firm own sufficient shares to effectively select enough board members to influence dividend policy? In the absence of any other information, a cutoff of 20 percent is often used: if the investing firm owns less than 20 percent, it is deemed to be minority passive. However, this is an arbitrary cutoff, and what really matters is influence on dividend policy. There are situations where, even though the investing firm owns more than 20 percent of the voting shares, it is unable to select any board members.

Minority active occurs when the investing firm owns less than 50 percent of the voting shares of the subsidiary but has the ability to influence (i.e., is active) if or when the subsidiary pays dividends. In the minority active case, accounting for the investment is done using the equity method. Note that, by definition, minority active can only occur when no other firm or cohesive group of investors has a majority stake in the subsidiary. As above, in the absence of any other information, a cutoff of 20 percent is often used (i.e., if the investing firm owns 20 percent or more, it is deemed to be minority active). However, this is once again an arbitrary cutoff, and what really matters is whether or not the investing firm has influence on dividend policy. There are situations where, with much less than 20 percent of the voting shares, a firm is able to choose a majority of board members and thereby control the amount and timing of the subsidiary’s dividends.

Majority occurs when the investing firm has more than 50 percent of the voting shares of the subsidiary. Here, the investing or “parent” firm has control because it can elect a majority of the board members, thereby choosing management and dictating the amount and timing of any dividend payments. In this case, the parent company’s accounting for the investment (for the shares owned in the subsidiary) is done using the equity method; however, the financial statements are presented on a “consolidated” basis.6 This means the investment will not be presented as a single-line item, but rather will be “consolidated” with the parent companies accounts as explained below.

The Cost Method of Accounting for Intercorporate Investments

The cost method is used, as noted above, when a firm has a minority passive investment in another firm. Under the cost method, as the name implies, the long-term intercorporate investment is recorded and presented at cost on the Balance Sheet (at the time the investment is made, an investment account is increased and cash is reduced) and recognizes any dividends paid to the investing firm as earnings on the date of record.7 That is, earnings from the investment are recognized when the investing firm is entitled to receive them. This contrasts with the parent firm picking up its share of profits (or losses) as earned by the subsidiary, which does not occur in the case of minority passive investors. Being a minority passive investor means the investing firm has no influence on the timing of dividend payments, and so revenue is included only when the parent is entitled to receive it.

There is one caveat to the above (not something about which the reader normally has to be aware but included here for completeness and to show the rational of the method): the dividends are considered earnings only if they are paid from postacquisition (i.e., after the date of the share purchase) retained earnings. If the dividend reduces the subsidiary’s retained earnings below what they were at the date the shares were acquired, the investing firm accounts for the dividend upon receiving it by reducing the investment account (cash up, investment down). This may sound complex, but illustrating the process with the following examples may help break it down.

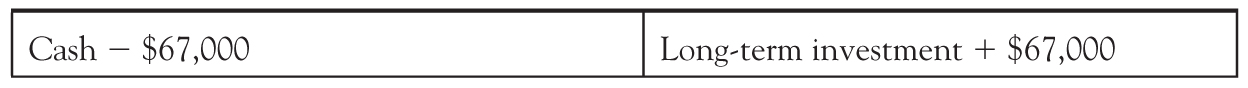

Assume a firm called Parent Co. buys 10 percent of the outstanding equity of Subsidiary Co. on January 1, 2017, for $67,000. At the time the shares are purchased, Subsidiary Co.’s Balance Sheet shows the following:

Subsidiary Co. Balance Sheet as at January 1, 2017

Parent Co., records its purchase of Subsidiary Co. shares on January 1, 2017, by increasing a long-term investment account and reducing cash in the amount of $67,000.

Parent Co. entry on January 1, 2017

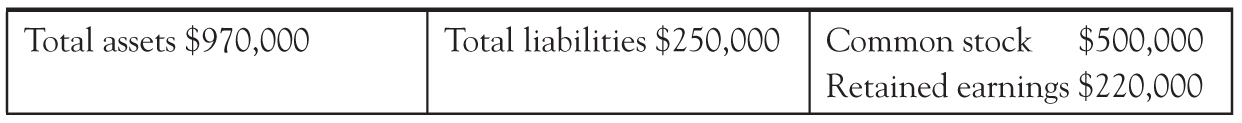

In example 1, assume Subsidiary Co. earns $50,000, pays no dividends during 2017, and has the following year-end Balance Sheet (note that retained earnings increase by $50,000 from $170,000 to $220,000):

Subsidiary Co. Balance Sheet as at December 31, 2017, for example 1

In this case, Parent Co. makes no entry for any of Subsidiary Co.’s earnings because no dividends were declared.

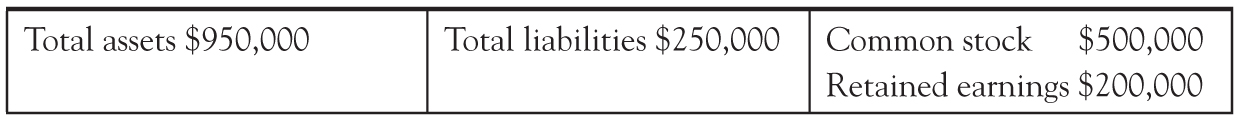

In example 2, assume Subsidiary Co. still earns $50,000 but now declares and pays a $20,000 dividend during 2017. This makes its assets and retained earnings $20,000 lower than in example 1. Subsidiary Co.’s year-end Balance Sheet would be the following:

Subsidiary Co. Balance Sheet as at December 31, 2017, for example 2

In this case, Parent Co. receives its 10 percent share of the $20,000 dividend, or $2,000. Parent Co. would record the $2,000 it received as an increase in cash on the Balance Sheet and an increase in dividend revenue on the Income Statement (which is closed at year end to retained earnings). Remember, in this example Parent Co. and Subsidiary Co. are two separate firms and each has its own set of accounting records.

Parent Co. entry on receipt of dividends during 2017

In example 3, assume Subsidiary Co. still earns $50,000 but now declares and pays a dividend of $120,000 during 2017. This makes its assets and retained earnings $120,000 lower than in example 1. Its year-end Balance Sheet would be the following:

Subsidiary Co. Balance Sheet as at December 31, 2017, for example 3

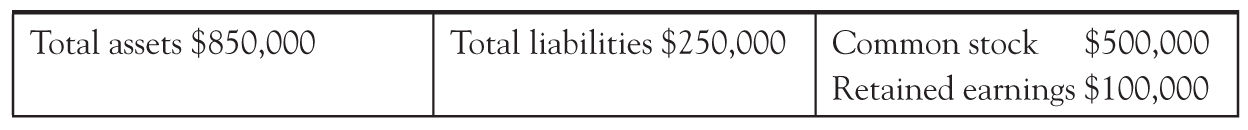

In this case, Parent Co. receives its 10 percent share of the $120,000 dividend, or $12,000 in cash. The first part of the accounting entry is simple: cash goes up $12,000 on the Balance Sheet. What about the second part, the entry for the Income Statement? Does it make sense for Parent Co. to record the full $12,000 as dividend revenue? Absolutely not. Notice that when Parent Co. purchased Subsidiary Co., the latter had retained earnings of $170,000. When it bought 10 percent of Subsidiary Co.’s shares, Parent Co. essentially purchased 10 percent of these retained earnings. After Parent Co.’s share purchase on January 1, 2017, Subsidiary Co. earned a total of $50,000 and paid dividends totaling $120,000. This means Subsidiary Co.’s retained earnings decrease by the $70,000 difference ($120,000 − $50,000). Parent Co. gets 10 percent of this decrease ($7,000). This $7,000 decrease is a return of Parent Co.’s initial investment and is not revenue.

In example 3, when the dividends are received in 2017, Parent Co. would record an increase in cash of $12,000, a decrease in its Investment in Subsidiary Co. of $7,000 (from $67,000 down to $60,000), and dividend revenue of $5,000.

Parent Co. entry on receipt of dividends during 2017

The rational is as follows: Only those dividends paid from the earnings that Subsidiary Co. makes after Parent Co.’s purchase of shares can be treated as revenue by Parent Co. Any dividends paid from retained earnings (which were purchased by Parent Co. as part of its 10-percent equity stake) are a return of the initial investment and treated as a reduction in Parent Co.’s investment in Subsidiary Co. account. Imagine an extreme case where Subsidiary Co. paid a $170,000 dividend on January 2, 2017 (the day after the Parent Co. purchase). Would any of the $17,000 (10 percent) in dividends that Parent Co. would receive be recorded as revenue? No, because Subsidiary Co. has not yet had earnings after the share purchase and the full $17,000 would be a return of the acquisition price paid by Parent Co.

Going forward in example 3, Parent Co. will use Subsidiary Co.’s adjusted retained earnings amount of $100,000 to determine if future dividends are revenue or a reduction in the investment account (i.e., if future dividends paid by Subsidiary Co. reduce its retained earnings below, then a reduction in Parent Co.’s investment account will occur). Only dividends paid from Subsidiary Co.’s future earnings (without having to dip into the $100,000 adjusted retained earnings amount) will be recorded as revenue by Parent Co. Also, it is important to note that once it is written down (reduced), the investment account is not written back up (increased), even if Subsidiary Co.’s retained earnings increase.8

A final point: Under the cost method of accounting for intercorporate investments, the investment account is not written down (reduced) when Subsidiary Co. incurs losses. The investment would be written down if, as noted above, Subsidiary Co. pays dividends that lower or further lower retained earnings below what they were when Parent Co. purchased shares. Of course, as with any asset, if Parent Co. at any point believes that its investment in Subsidiary Co. has sustained a permanent decline in its value to below the accounting value, then Parent Co. must make an adjustment in its accounting books to take that value decline into account.

The Equity Method of Accounting for Intercorporate Investments

The equity method is used, as noted above, when a firm has a minority active investment or a majority stake in another firm.9 Under the equity method, the long-term intercorporate investment is initially recorded at cost on the Balance Sheet (investment up, cash down). The method then picks up the investing firm’s share of the subsidiary’s earnings or losses (investment up or down and an Income Statement item up or down) and recognizes any dividends received from the subsidiary as a reduction of the investment (cash up, investment down).10 That is, the investing firm recognizes earnings or losses from the investment in the same period as they are recognized by the subsidiary. This happens because being a minority active investor (or a majority owner) means the investing firm is able to influence the timing of the subsidiary’s dividend payments. This means the investing firm has at least some control over when it receives the dividends and could take them in the period they are earned by the subsidiary. It would make no sense to allow the investing firm’s management to manipulate earnings by choosing when it pays itself dividends.

For example, assume a firm called Parent Co. buys 30 percent of the outstanding equity of Subsidiary Co. on January 1, 2017, for $201,000. At the time of purchase, Subsidiary Co.’s Balance Sheet shows the following:

Subsidiary Co. Balance Sheet as at January 1, 2017

Parent Co. records its purchase of Subsidiary Co. shares on January 1, 2017, by increasing a long-term investment account and reducing cash.

Parent Co. entry on January 1, 2017

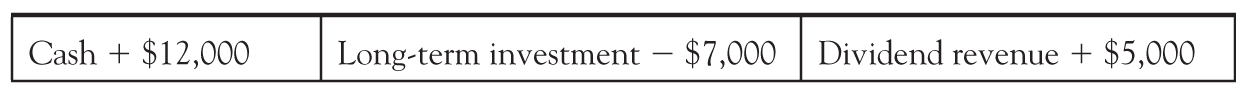

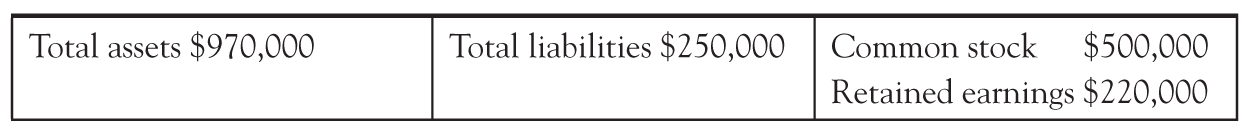

In example 1, assume Subsidiary Co. earns $50,000, pays no dividends during 2017, and shows the following year-end Balance Sheet:

Subsidiary Co. Balance Sheet as at December 31, 2017, for example 1

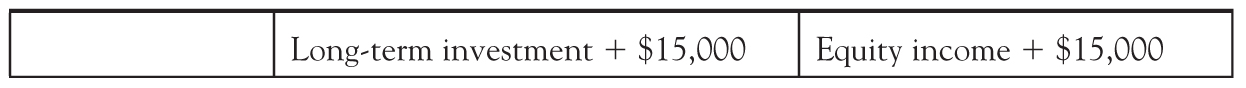

In this case, Parent Co. increases its investment account by $15,000 (its 30 percent share of Subsidiary Co.’s profit) and records an Income Statement line item called “income from equity investment in Subsidiary Co.” (or more simply, “equity income”) of $15,000. Thus, Parent Co. picks up its share of the profits or losses of Subsidiary Co.

Parent Co. entry on receipt of dividends during 2017

In example 2, assume Subsidiary Co. earns $50,000 and pays a $20,000 dividend during 2017. This reduces its assets and retained earnings by $20,000 (when compared to example 1). Subsidiary Co.’s year-end Balance Sheet would be the following:

Subsidiary Co. Balance Sheet as at December 31, 2017, for example 2

In this case, Parent Co. receives its 30 percent share of the $20,000 dividend, or $6,000. As in example 1, Parent Co. records its share of Subsidiary Co.’s $50,000 profit with an increase in the investment account of $15,000 (Parent Co.’s 30 percent share of Subsidiary Co.’s profit) and a line item in the Income Statement of $15,000. Then Parent Co. records the $6,000 dividend received as an increase in cash and a decrease in its investment account of $6,000. Thus, Parent Co.’s “investment in Subsidiary Co.” account goes up a net of $9,000 (the $15,000 increase for its share of the profits less the $6,000 for its share of the dividends).

Parent Co. entry on receipt of dividends during 2017

There is no need to provide a third example for how the equity method would handle a higher dividend because the only difference would be the larger increase in cash and reduction in the investment account due to the increased dividend.

Is that it? Not even close. The equity method is in fact much more complex. The equity method has additional adjustments for unrealized intercompany profits and for any differences between what Parent Co. paid for Subsidiary Co.’s assets and liabilities and what its book (accounting) values were. In effect, using the equity method results in the same net income as when a firm consolidates a subsidiary. Consolidation is described next.

Summary of the accounting for the cost versus equity methods:

Consolidations

The financial statements of public firms normally do not reflect the accounting records of the firm being examined. The statements are rather an accounting fiction of what the firm and all its subsidiaries would look like if they comprised a single legal entity. Consider the following chart, where a holding company called Parent Co. fully owns three operating firms called Subsidiary 1, Subsidiary 2, and Subsidiary 3:

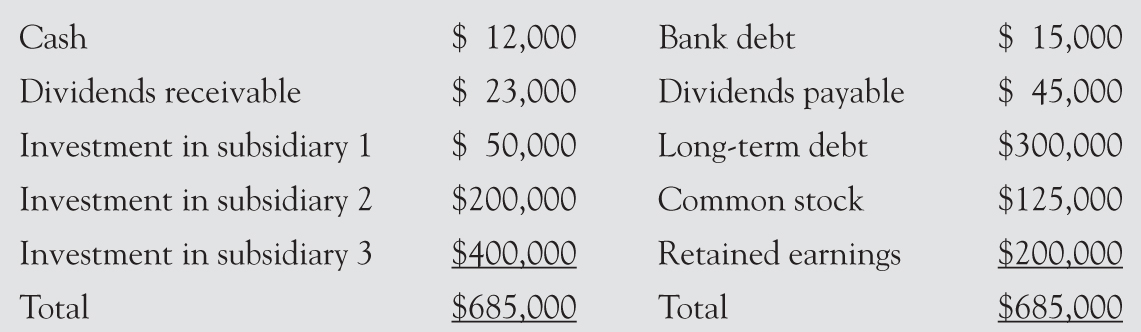

The nonconsolidated Income Statement and Balance Sheet of the Parent Co., as shown in Exhibit 1.1, are completely uninformative. What are the assets of Parent Co.? Some cash, dividends receivable from the operating firms, and its investments in the three subsidiaries. What are the liabilities of Parent Co.? It has some debt and owes some dividends to its owners. But Exhibit 1.1 says nothing about the sales or costs of the combined organization, nor does it provide any sense of the breakdown of various assets or liabilities. There is no financial analysis that can be done to understand the nature of the firm’s business. Although legally accurate, these statements are not useful to an outsider trying to understand Parent Co. or predict its future cash flows.

In contrast, consolidated financial statements present a fictional picture of what the firm would look like if it were a single legal entity (if the parent firm and its subsidiaries were combined). This is needed to understand the nature of the firm’s business and predict future cash flows. In other words, the legal reality of separate firms, where one owns the others, must be undone. The legal reality is replaced with a combination of each subsidiary’s assets, liabilities, revenues, and expenses rather than a line on the Balance Sheet for investment in subsidiary and a line on the Income Statement for dividend revenue or equity income.

Exhibit 1.1: An Unconsolidated Income Statement and Balance Sheet

Parent Co. Income Statement for the year ended December 31, 2017

Dividend revenue |

$52,000 |

Interest expense |

$20,000 |

Profit before tax |

$32,000 |

Income tax |

$10,000 |

Net income |

$22,000 |

Parent Co. Balance Sheet as at December 31, 2017

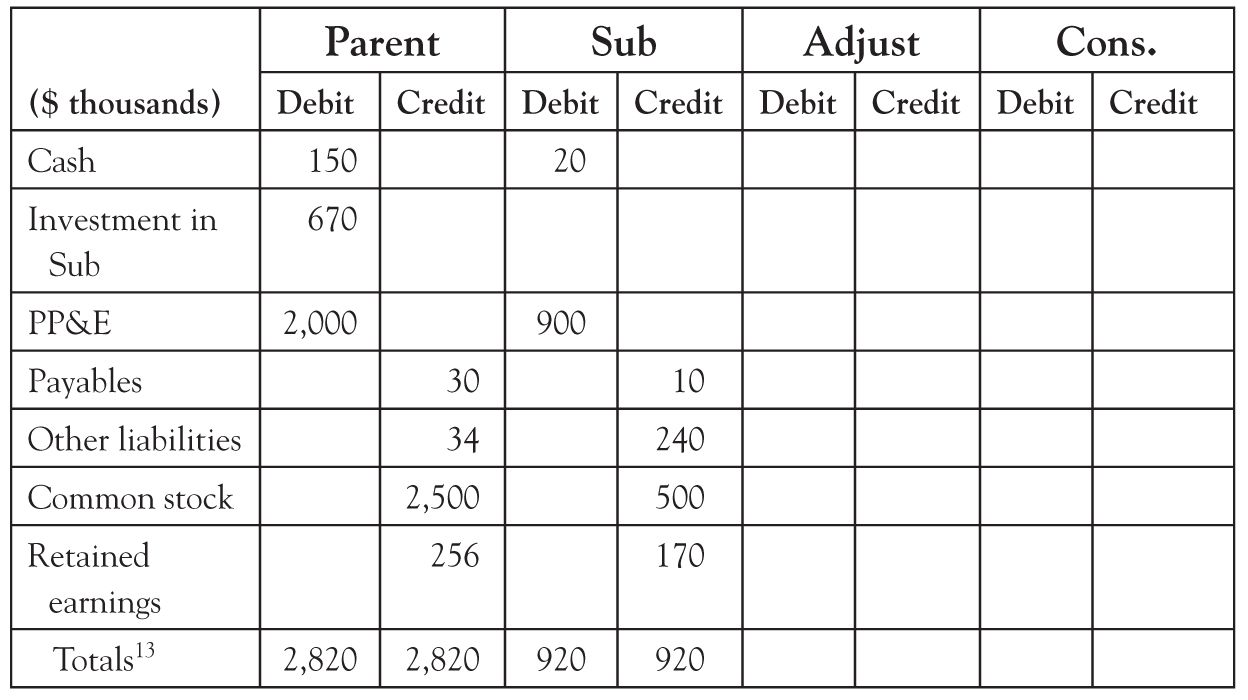

Consolidated financial statements are prepared from a worksheet. When consolidating the statements of a parent and a single subsidiary, the Parent Co. accounts are listed in the first two columns (debits and credits) and are followed by the Subsidiary Co. accounts (debits and credits).11 Thus, the two firms’ actual accounts are listed in the first four columns of the worksheet.12 The next two columns are the adjustments, which is the consolidation process discussed below. Finally, each line is totaled horizontally, and the last two columns are the consolidated financial statements.

The Consolidated Balance Sheet

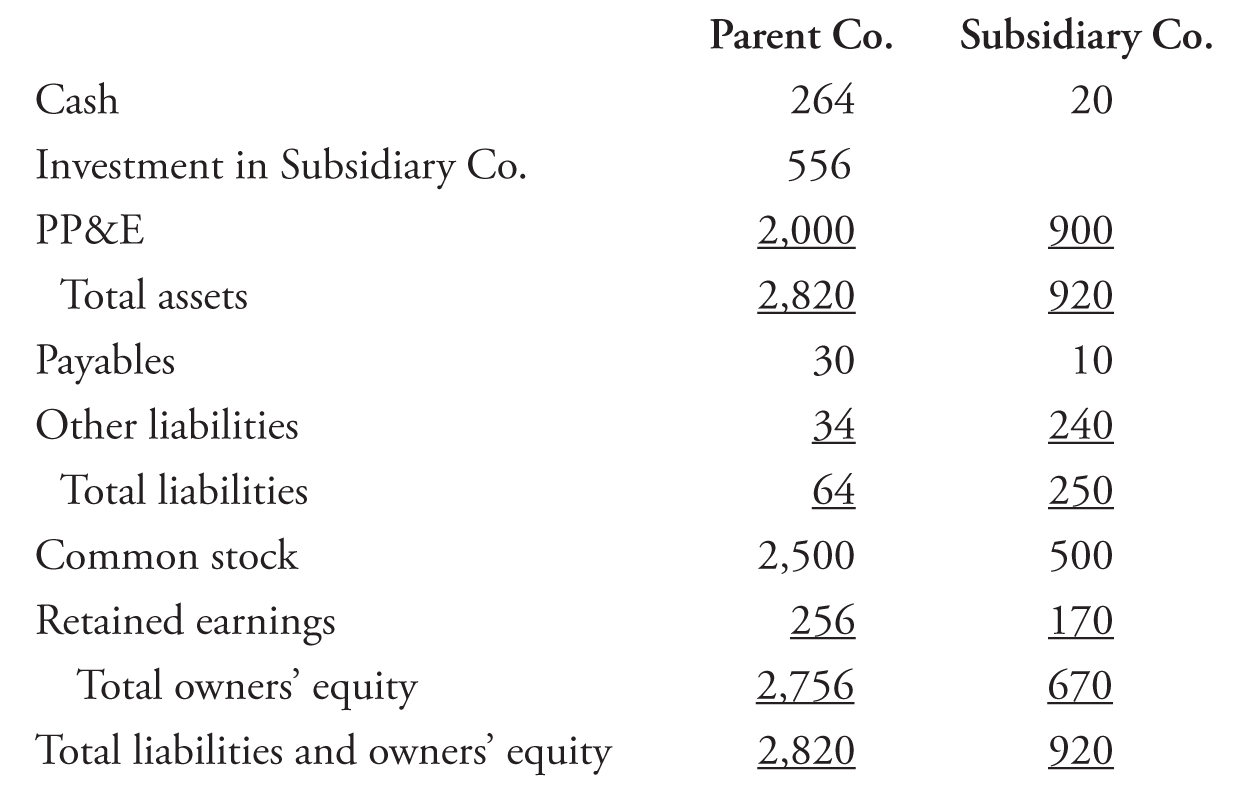

Let us start with a very simple example. The date is January 2, 2017, and Parent Co. has just purchased 100 percent of the outstanding common stock of Subsidiary Co. for $670,000. On the date of the acquisition the Balance Sheets of each company are as follows:

Balance Sheet as at January 2, 2017 ($ thousands)

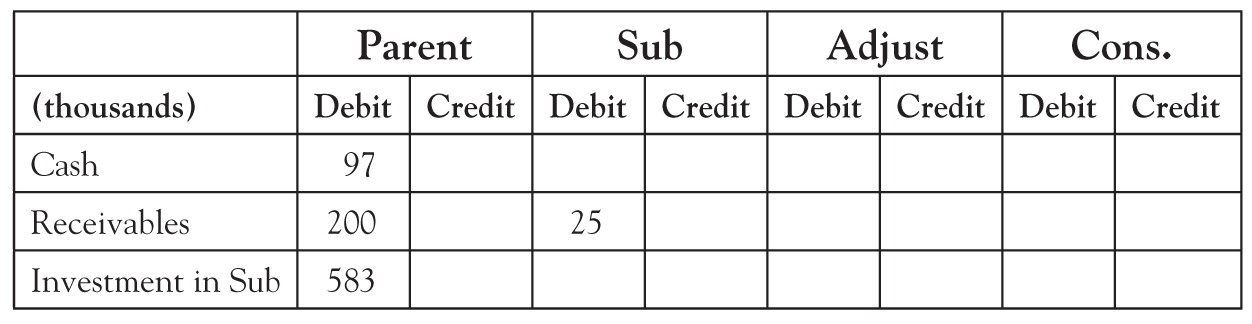

These two Balance Sheets can be placed into a worksheet as follows:

Note that, in the example above, Parent Co.’s 100 percent ownership investment in Subsidiary Co., at $670,000, is exactly the net book value (assets less liabilities) of Subsidiary Co. ($920,000 less $250,000). This is an extreme simplification. In reality, an acquirer (Parent Co. in this example) would almost always pay above book value (i.e., above accounting value) for a firm. Why do acquirers typically pay more for their acquisition target than the target’s accounting value? Because the accounting value does not include human capital, distribution rights, the value of the organizational form, and firm-created intangibles (copyrights, trade-names, and patents). In addition, accounting values do not reflect economic reality. The economic values of assets are likely to be more than the accounting values, the economic value of the current liabilities are likely to be close to accounting values, and the economic value of the long-term liabilities could be more or less than the accounting values. How the differences between economic and accounting values are treated will be discussed below. For now, assume a miracle has occurred and that the economic and accounting values of Subsidiary Co. are exactly the same, which is what Parent Co. paid.

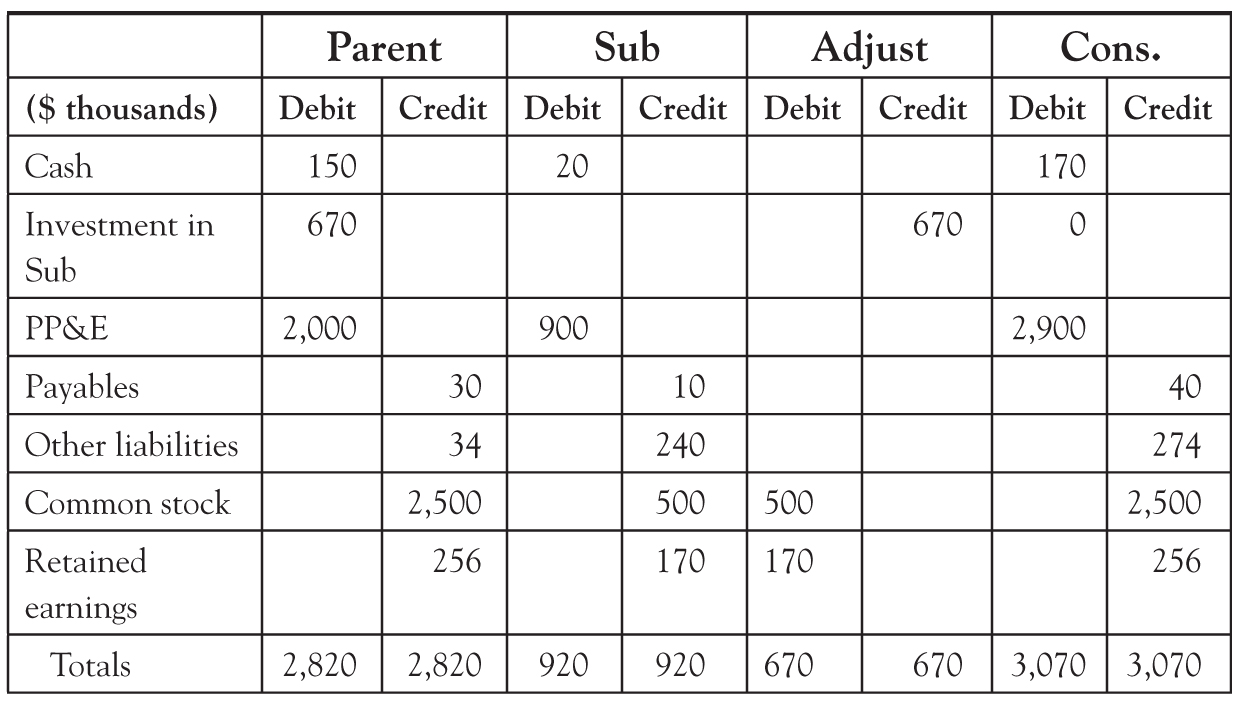

To create a consolidated Balance Sheet for this example on the acquisition date, two adjustments are required. First, Parent Co.’s investment in Subsidiary Co. must be removed from Parent Co.’s consolidated Balance Sheet and replaced with Subsidiary Co.’s assets and liabilities as though these assets and liabilities were part of a single entity. This is done by reducing the investment in Subsidiary Co. account to zero with a credit of $670,000 (and adding across the columns will now show all the assets and liabilities of the two firms). Second, the equity of Subsidiary Co. must be removed, with a debit of $500,000 to common stock and $170,000 to retained earnings, from the combined firm. When the two firms are combined and presented as one firm, called Parent Co. consolidated, the only owners are those of Parent Co. (who own 100 percent of Subsidiary Co. through their ownership of Parent Co.). The Balance Sheet of Parent Co. consolidated will show 100 percent of the assets and liabilities of Subsidiary Co. and Parent Co.’s common stock and retained earnings ($2,500,000 and $256,000, respectively). Including the investment in Subsidiary Co. account or the owner’s equity of Subsidiary Co. would double-count these amounts. In other words, what is being added to the Parent Co.’s accounts are the assets and liabilities of Subsidiary Co. Thus, the investment in Subsidiary Co. and the owners’ equity of Subsidiary Co. must be removed (reduce, credit, investment in Subsidiary Co. $670,000; reduce, debit, common stock $500,000; and reduce, debit, retained earnings $170,000).

With these two adjustments, the spreadsheet now looks as follows when we add the rows across and put the totals in the consolidated debit and consolidated credit columns:

The last two columns of the spreadsheet provide the consolidated Balance Sheet as follows:

Parent Co. consolidated Balance Sheet as at January 2, 2017 ($ thousands)

This is the start of the consolidation process: a consolidated Balance Sheet at the date of acquisition. The single line of the investment account has been replaced by the assets and liabilities of the subsidiary. Also, remember that the consolidated Balance Sheet conveys a fiction that exists only in the accounting world (it is an accounting fiction). In fact, these are two separate firms, and in the legal records of Parent Co., its investment in Subsidiary Co. is listed at $670,000.

A More Realistic Example

Let us now make the above example more realistic in two ways: First, Parent Co. no longer buys 100 percent of Subsidiary Co. Second, Parent Co. pays more than the accounting value for Subsidiary Co.’s assets less liabilities. The date is still January 2, 2017, and Parent Co. has just purchased 80 percent (not 100 percent as above) of the outstanding common stock of Subsidiary Co. for $556,000.

The Balance Sheet of Subsidiary Co. is unchanged from the first example. The Balance Sheet of Parent Co. has two changes: cash is up $114,000 (from $150,000 to $264,000) and investment in Subsidiary Co. is down $114,000 (from $670,000 to $556,000). These changes occur because Parent Co. only purchased 80 percent of Subsidiary Co. (instead of 100 percent) and paid $556,000 (instead of $670,000), leaving Parent Co. with $114,000 in additional cash.

On the date of acquisition, the Balance Sheets of each company are as follows:

Balance Sheet as at January 2, 2017 ($ thousands)

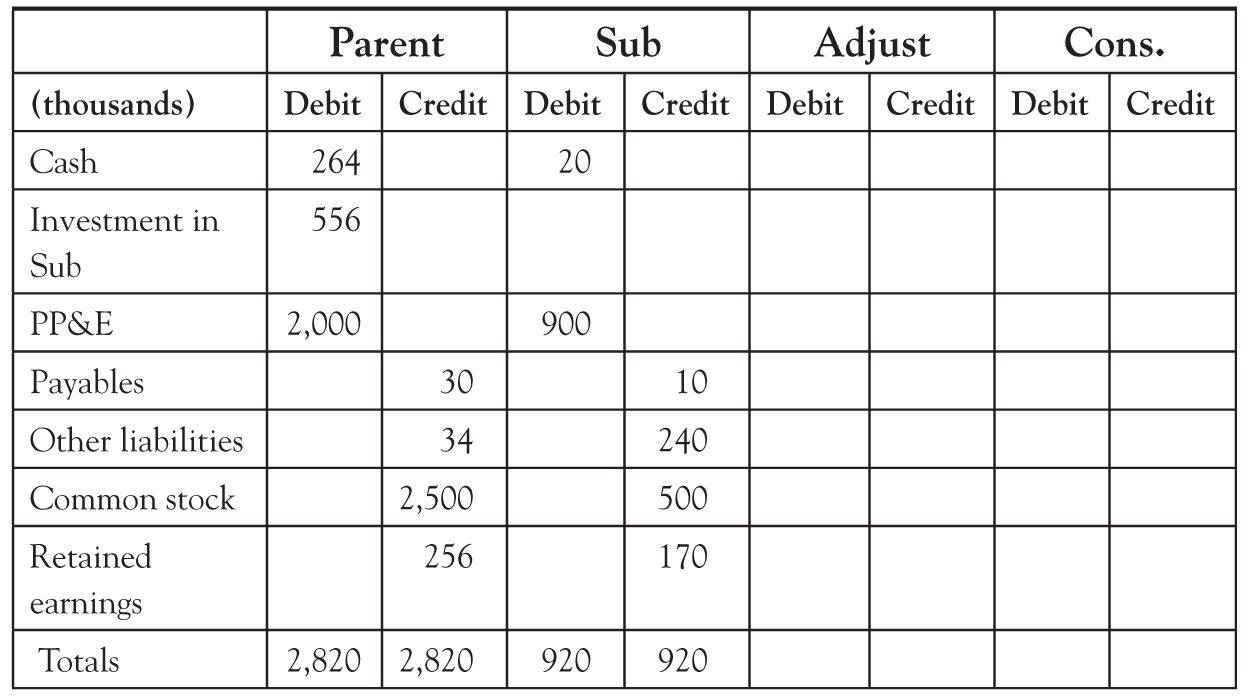

These two Balance Sheets can be placed into a worksheet as follows ($ thousands):

As above, the consolidation process begins by reducing Parent Co.’s account for its investment in Subsidiary Co. to zero (with an adjusting credit to investment in Subsidiary Co. of $556,000) and then eliminating the equity of Subsidiary Co. (with adjusting debits of $500,000 to common stock and $170,000 to retained earnings). However, now the adjustments do not balance (the debits are still $670,000, but the credit is only $556,000). What happened? Two things: First, Parent Co. does not own 100 percent of Subsidiary Co. as it did above. Second, Parent Co. paid more than Subsidiary Co.’s accounting value when it purchased 80 percent of Subsidiary Co.’s shares. Let us deal with each of these in turn.

First, let us deal with the fact that Parent Co. does not own 100 percent of Subsidiary Co. The adjustment still removes 100 percent of the Subsidiary Co.’s equity in the consolidated totals. This is correct, as the consolidated entity should only show Parent Co.’s equity. However, when added across, the consolidation will show 100 percent of Subsidiary Co.’s assets and liabilities, whereas Parent Co. only owns 80 percent. What about the other 20 percent? Someone else owns it. It does not matter who owns it: the only thing that matters to our present exercise is that it is not Parent Co.

There are two possible ways to handle the 20 percent difference: One rarely used alternative is called “proportional” or “partial” consolidation.14 This method records (adds) only the percentage Parent Co. owns of Subsidiary Co.’s assets and liabilities (in this case 80 percent). This means adjustments reducing the subsidiary’s assets and liabilities (in this case 20%) would have to be made. The second method, what is normally done, is called “full consolidation” (or just “consolidation”). In this method, Parent Co. records 100 percentage of Subsidiary Co.’s assets and liabilities and then sets up a new account for the percentage it does not own (in this case 20 percent). The new account is called noncontrolling or minority interest. The account is listed as part of the consolidated Balance Sheets owners’ equity account.15 The amount in the account is calculated as the percentage not owned by the parent times the net book value (assets minus liabilities or owners’ equity) of the subsidiary. In this case, the amount is $134,000 (20 percent × $670,000).

So, we now have four adjusting entries: one to eliminate the investment account (a credit of $556,000); one to eliminate the common stock or equity of the subsidiary (a debit of $500,000); one to eliminate the retained earnings of the subsidiary (a debit of $170,000); and a new entry creating an account called noncontrolling interest (a credit of $134,000). Alas, the debits ($500,000 + $170,000 = $670,000) still do not equal the credits ($556,000 + 134,000 = $690,000), taking us to our final adjustment.

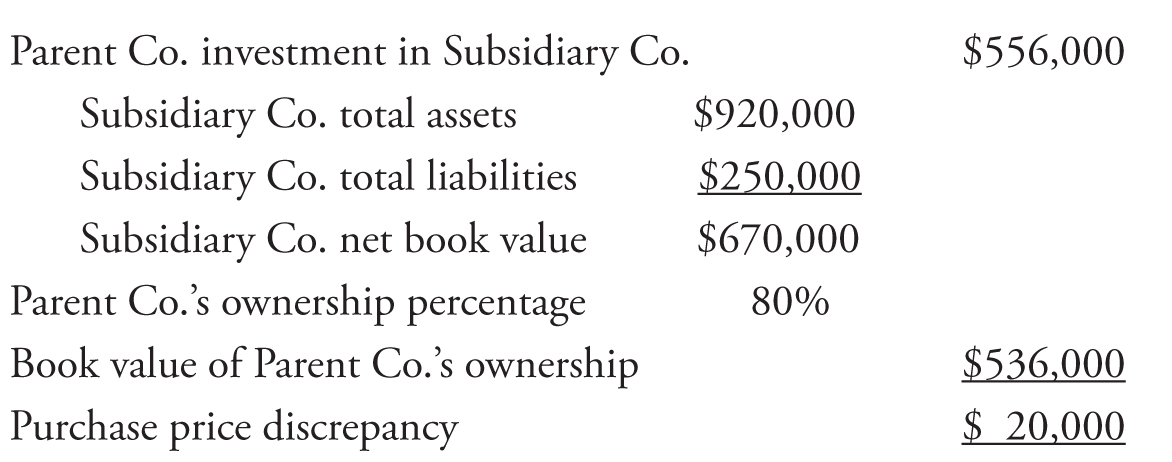

Now let us deal with the fact that Parent Co. paid more than accounting value for Subsidiary Co. As can be seen from the calculation below, Parent Co. paid $20,000 more than the underlying book value of the Subsidiary Co.’s assets and liabilities. Accountants call this a purchase price discrepancy.

Why did Parent Co. pay more for its ownership in Subsidiary Co. than the ownership percentage times the accounting values? As noted above, the “fair” or economic values of the underlying assets and liabilities may be worth more or less than their accounting values. In addition, Subsidiary Co. may have human capital, distribution rights, the value of the organizational form, and firm-created intangibles (copyrights, trade-names, and patents) not included in the accounts.

How is the purchase price discrepancy accounted for? This can become somewhat complex. In effect, each of Subsidiary Co.’s assets and liabilities will be separately valued (estimated). This includes computing values for any intangible assets (even those with no accounting value). Then an adjustment will be made for the differences between these “fair” values and the accounting values. Is the adjustment for 100 percent of this difference even when Parent Co. purchased less than 100 percent of the subsidiary? No. The adjustment is for the difference times Parent Co.’s ownership percentage.

For example, assume the economic and accounting values in our example above are the same for all assets and liabilities except PP&E.16 Further, assume the economic value of PP&E is $915,000. Because the accounting value is $900,000, this is a difference of $15,000. The adjustment to PP&E is an increase or debit of $12,000 (calculated from $15,000 × 80 percent).

However, the purchase price discrepancy and the amount by which the consolidated Balance Sheet does not balance is $20,000. The adjustment to PP&E is only $12,000. Where is the final $8,000 required to balance all the adjustments? This is what accountants call “goodwill.” To an accountant, goodwill is the portion of the purchase price discrepancy that the accountant cannot attribute to differences between the purchase price and the fair market value of the firm’s assets and liabilities. This last line should be reread several times. It is important that readers understand what goodwill on the Balance Sheet means. It does not represent goodwill that Parent Co. created over time by providing quality products and services on time in a friendly, helpful manner. Rather, it represents what the Parent Co. paid above the identifiable market value of the subsidiary’s assets and liabilities (in other words, the $8,000 required to balance all the adjustments). Goodwill can only exist after an acquisition.

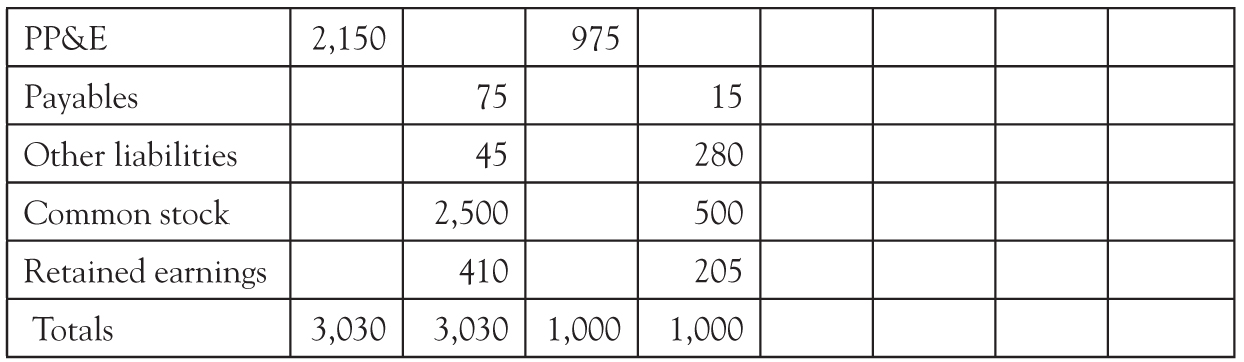

The following spreadsheet can now be prepared for our more realistic example ($ thousands):

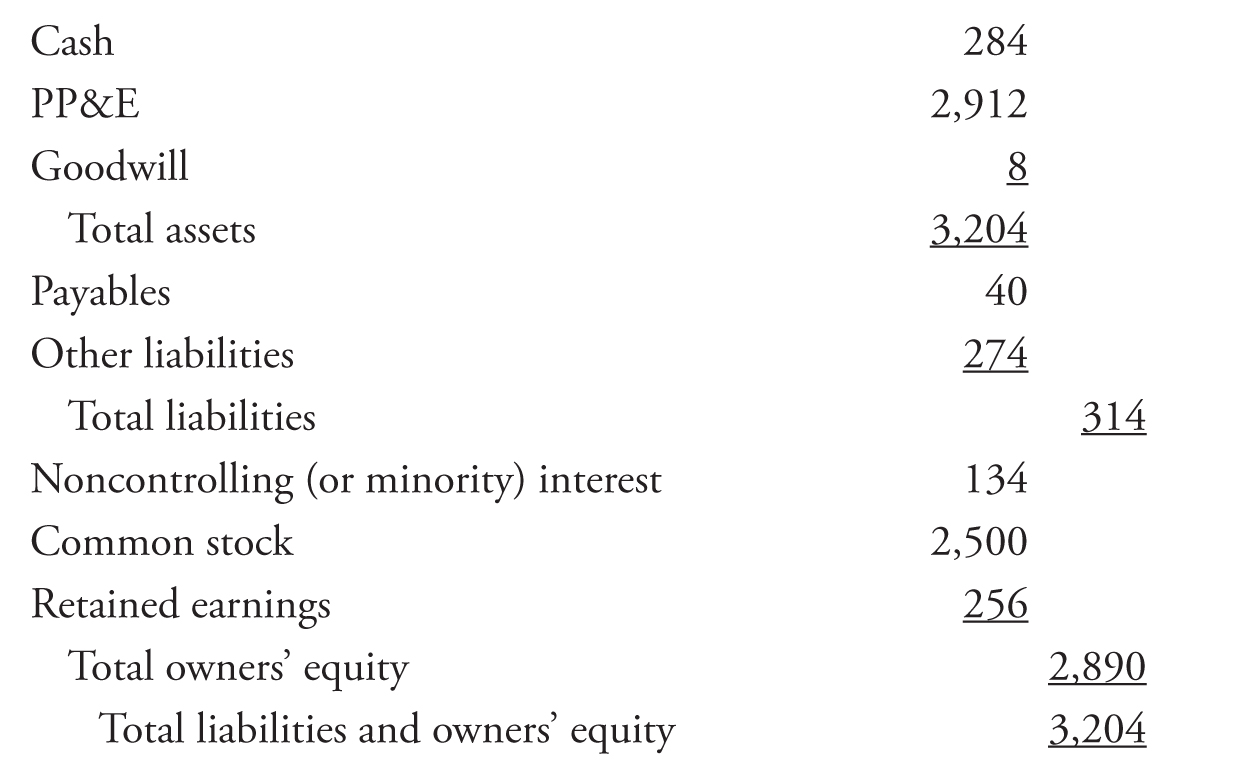

And from the spreadsheet, we can now create a consolidated Balance Sheet:

Parent Co. consolidated Balance Sheet as at January 2, 2017 ($ thousands)

The Consolidated Income Statement

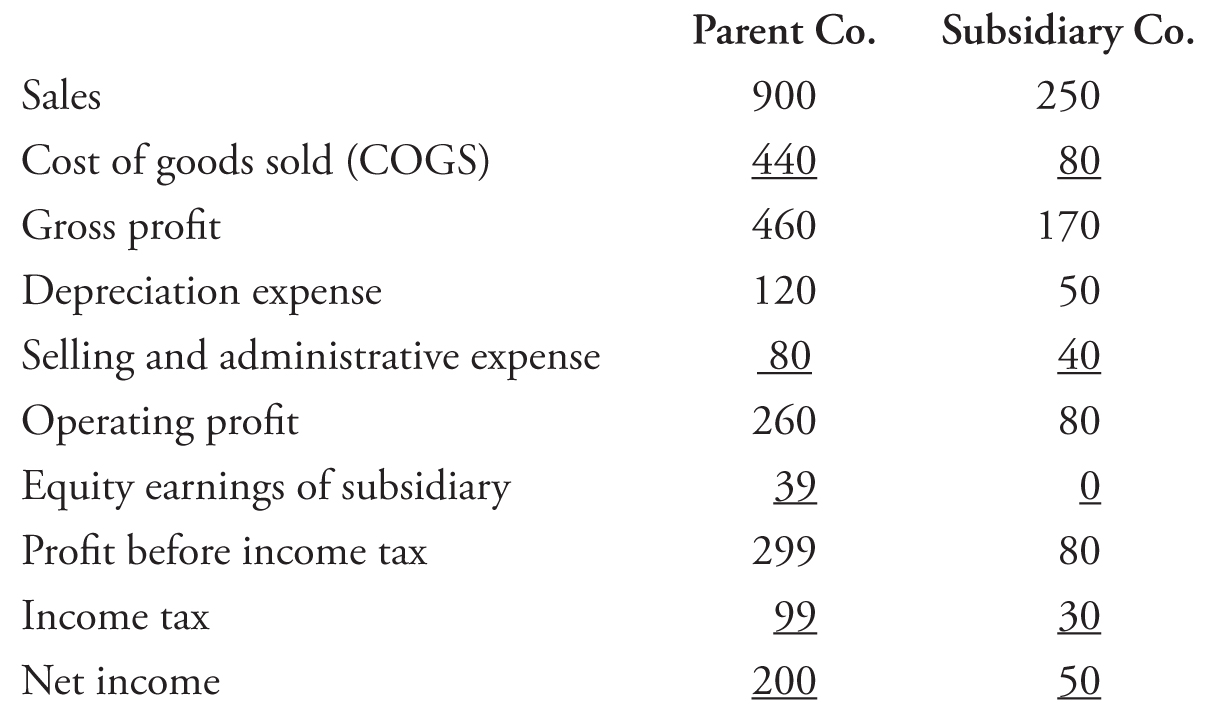

Let us now continue the example above (Parent Co. purchases 80 percent of Subsidiary Co. for $556,000) to the end of the year. We start with the year-end consolidated Income Statement, and then turn to the consolidated Balance Sheet. The date is now December 31, 2017, and Parent Co. and Subsidiary Co. have the following individual Income Statements for the year:

We also have some additional information: Parent Co. purchased $40,000 of product from Subsidiary Co. during the year, paying $28,000 to Subsidiary Co. by year end and leaving $12,000 unpaid. Parent Co. resold all of this product to its customers for $45,000. Also, Parent Co. declared and paid a dividend of $46,000, while Subsidiary Co. declared and paid a dividend of $15,000.

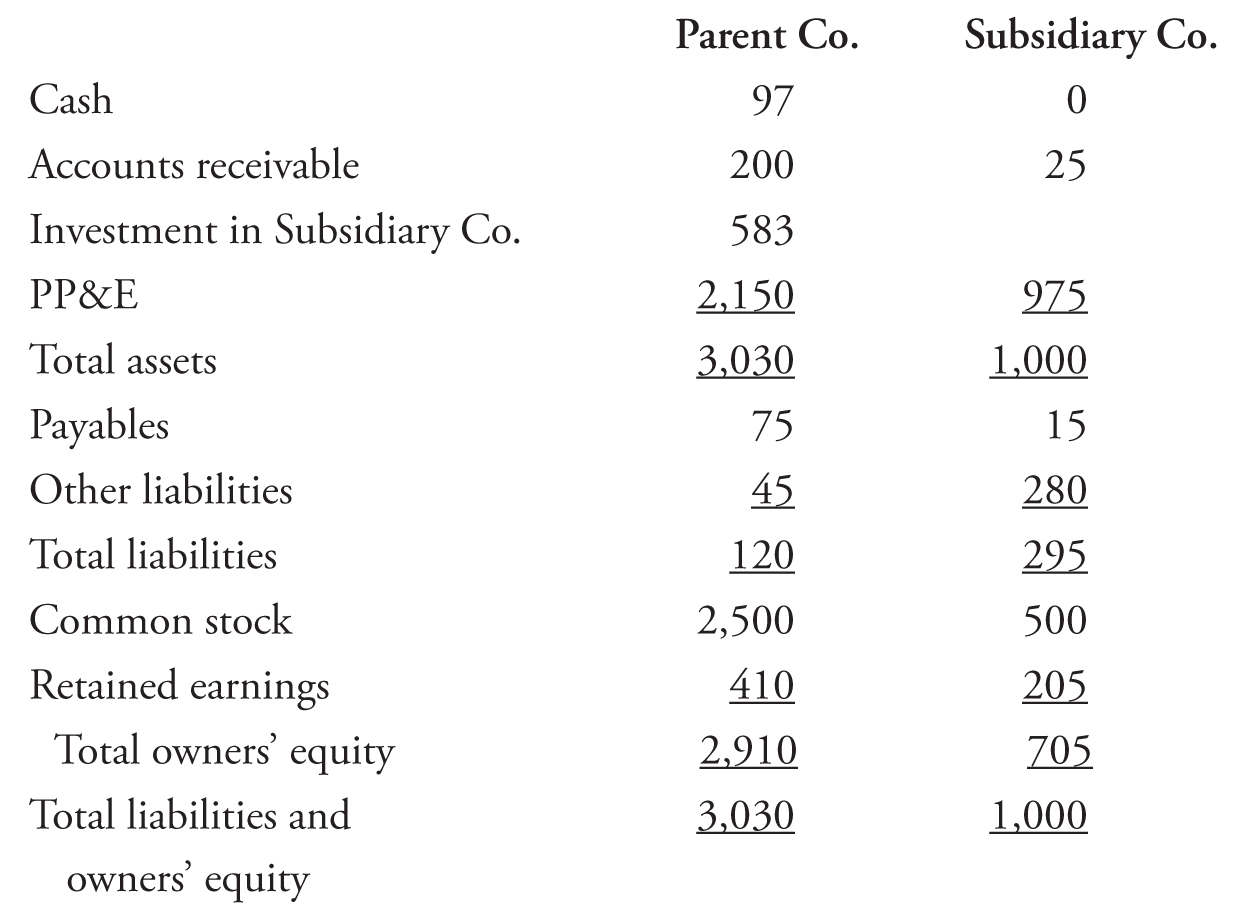

As with the Balance Sheet, creating a consolidated Income Statement is done on a worksheet. Note that the difference in the total debits and total credits of each company is its profit (or loss).

Income Statements for the year ended December 31, 2017 ($ thousands)

The initial spreadsheet looks as follows ($ thousands):

The first adjustment is for any intercompany transactions that arise when a firm sells its products (or provides services) to a related firm. Assume that all of a subsidiary’s sales are to its parent company and that none of this product is resold at year end. Has the combined firm made any profit on these sales? The subsidiary shows a profit, but what happened was simply a transfer from one related entity to another. In effect, a firm cannot recognize sales, costs, profits, or losses by selling products (or providing services) to itself. A profit (or loss) can only be made when there are sales to unrelated parties.

In our example, Subsidiary Co. sold $40,000 worth of product to Parent Co. Because Parent Co. owns Subsidiary Co. (even if only 80 percent of it), this is an intercompany sale on which Subsidiary Co. realized a gross profit of $27,200. How is that computed? Subsidiary Co. has gross profit of $170,000 on $250,000 sales. This is a gross profit percentage of 68 percent ($170,000/$250,000). Subsidiary Co.’s gross profit on $40,000 of sales is therefore $27,200 ($40,000 × 68 percent). Separately, Parent Co. resold all of this product for $45,000, realizing a gross profit of $5,000 (its sale price of $45,000 less the cost of $40,000 that Parent Co. paid to Subsidiary Co.). Combining the profits of both parent and subsidiary gives us $32,200 ($27,200 + $5,000).17

However, for consolidation purposes, the intercompany sale itself requires an adjustment to avoid double counting. In this case, the Subsidiary Co.’s $40,000 sale must be removed (with a debit) and the Parent Co.’s $40,000 cost must be removed (with a credit). Note, if Parent Co. and Subsidiary Co. were one legal entity (remember, the two firms being one is the consolidation fiction), then the revenue from the sale to the unrelated customer would be the $45,000 Parent Co. sold the product for, and the cost from an unrelated suppler would be the $12,800 Subsidiary Co. purchased the product for from the unrelated supplier. The difference is the $32,200 profit noted above. The removal of the intercompany sale and cost does not affect profits, but it does affect the total amounts for sales and COGS and the gross margin (gross profit/sales).

Next, notice Parent Co. has “equity earnings” in the amount of $39,000. Remember, as noted above, the equity method is used in cases of majority ownership, and it requires the Parent Co. to pick up its share of the subsidiary’s earnings for the year. However, the reader may note that the $39,000 amount is less than 80 percent of Subsidiary Co.’s profit of $50,000, which would have been $40,000. Why is Parent Co.’s equity earnings account $39,000 and not $40,000? Remember the closing comment from the end of the explanation of the equity method above: the equity method has additional adjustments for (1) unrealized intercompany profits and (2) differences between what the parent paid for the subsidiary’s assets and liabilities, on the one hand, and the book (accounting) values, on the other. We handled the first by eliminating intercompany sales and costs and assuming there were no unrealized profits left at year end. Now let us consider the second.

Above, on the start-of-the-year consolidated Balance Sheet, the PP&E is increased by $12,000 at the date of acquisition (January 2, 2017). This increased amount must now be depreciated over the assets remaining life, which in this example is assumed to be done straight-line with no salvage value over 12 years, or $1,000 per year. This means that the consolidated Income Statement must show $1,000 of additional depreciation expense above what is shown on the combined accounts of Parent Co. and Subsidiary Co. An increase of $1,000 in the consolidated depreciation expense reduces the consolidated profit by $1,000. Because, as noted above, the equity method results in the same net profit as consolidations, this mean an adjustment of $1,000 is required to Parent Co.’s equity income. Parent Co.’s share of Subsidiary Co.’s profit is $40,000 before adjustments (Subsidiary Co.’s profits of $50,000 × Parent Co.’s share of 80 percent). A reduction of $1,000 for the additional consolidated depreciation reduces equity income to the $39,000 ($40,000 − $1,000) amount recorded by Parent Co. above. Thus, the equity income is $39,000 (the $40,000 of Parent Co.’s share of Subsidiary Co.’s profit less the extra $1,000 depreciation).

The next adjustment to the year-end consolidated Income Statement is to replace the single line item of equity earnings on Parent Co.’s Income Statement with the sales and expenses of Subsidiary Co. This is done with a debit in the adjustment column of $39,000 to equity earnings (thereby reducing them to zero) followed by a $1,000 increase to the consolidated depreciation (with a debit of $1,000). These two adjustments reflect Parent Co.’s ownership percentage times the net profit of the subsidiary (80 percent × $50,000 = $40,000) adjusted for the required increased depreciation.

With no other adjustments, adding across columns would include 100 percent of Subsidiary Co.’s revenues and expenses. However, Parent Co. only owns 80 percent of Subsidiary Co. The final adjustment in this example is for Parent Co.’s ownership being less than 100 percent. As with the consolidated Balance Sheet, Parent Co.’s consolidated Income Statement will record all of Subsidiary Co.’s sales and expenses (adjusted for any inter-company sales) and then set up a new expense to recognize the percentage it does not own (in this case 20 percent) and so is not entitled to.18 The new expense is called noncontrolling or minority interest expense. This can be slightly confusing, as there are now two accounts with a similar name, one called noncontrolling interest under owner’s equity on the Balance Sheet, the other noncontrolling interest after operating profits on the Income Statement. In our example, the adjustment for noncontrolling (or minority interest) expense is a debit (which reduces profit) of $10,000 (Subsidiary Co.’s net profit of $50,000 × the 20 percent outside ownership).

What about Goodwill? If the increased consolidated PP&E ($12,000 at the start of the year) has to be reduced over time, is the same not true of Goodwill ($8,000 at the start of the year)? Goodwill used to be amortized on a straight-line basis over a period not to exceed 40 years. Today the goodwill computation is much more complex: each year, goodwill must be evaluated. If management believes the reported value has, more likely than not, materially declined, then a quantitative revaluation is done. Essentially, the subsidiary’s future cash flows are estimated and discounted to create a value for the subsidiary. This value is then used to estimate the current value of goodwill. If the quantitative value has fallen during the year (accountants call this being “impaired”), it must be written down (never to be written back up). Otherwise, it is left alone (neither increased nor decreased). In this example, for simplicity, we assume there is no impairment.

The reader should appreciate how detailed the consolidation process can become. Each difference has to be adjusted over time. For example, differences in accounts receivable would be adjusted when collected, differences in inventory when sold, differences in debt when repaid, and so on. And this would be done for each account.

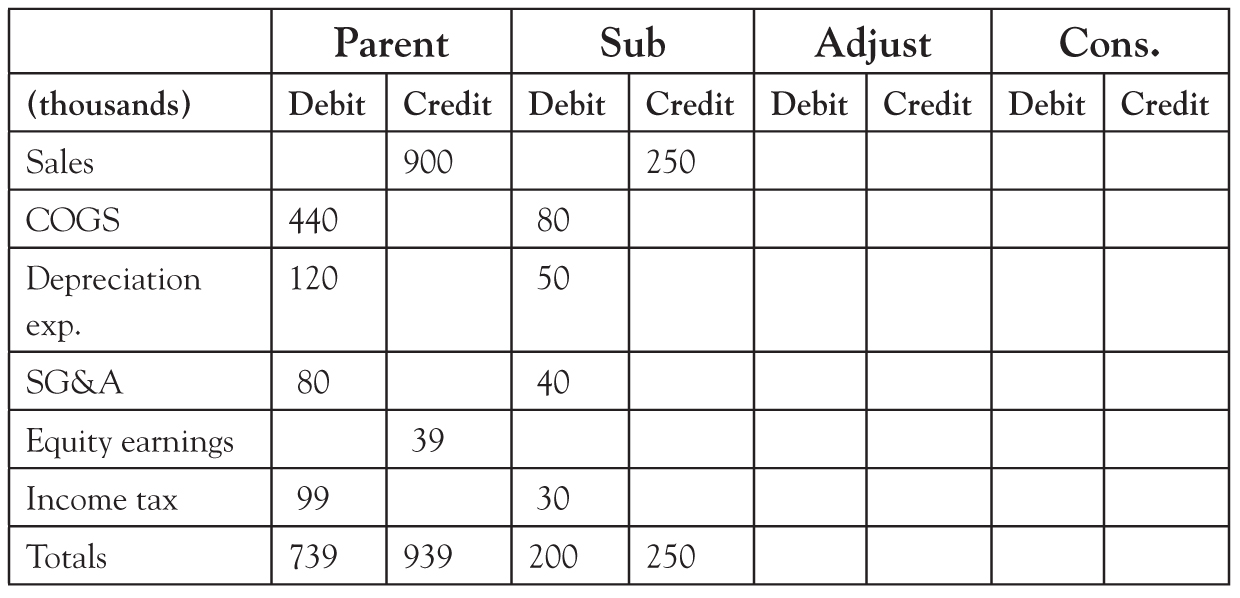

The adjustments are recorded onto the spreadsheet, cross totals are computed, and a consolidated Income Statement is prepared as follows ($ thousands):

Note that the Parent Co.’s unconsolidated net income (which included equity income of $39,000) matches Parent Co.’s consolidated net income. Why? It is by definition: as noted above, the equity method requires adjustments (in this case, the $1,000 reduction for the additional consolidated depreciation) so that a firm’s profit or loss using the equity method (the net of all the adjustments, in this case $40,000 − $1,000) must be the same as if a firm consolidates the subsidiary.

Parent Co. consolidated Income Statement for the year ended December 31, 2017 ($ thousands)

The Consolidated Year-End Balance Sheet

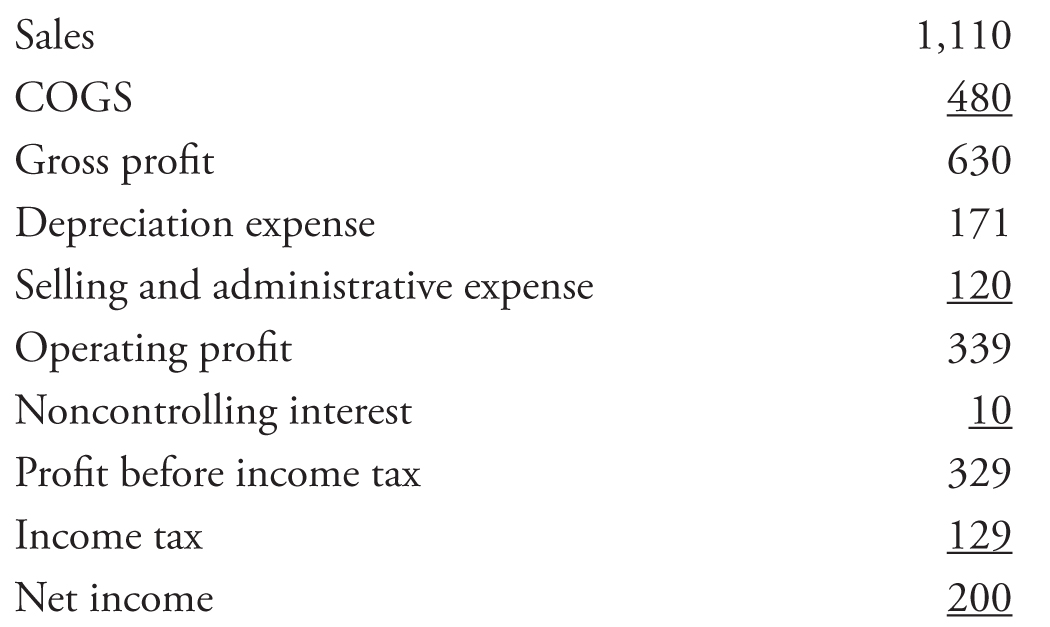

Now we turn to the year-end consolidated Balance Sheet. Naturally, at year end there would be numerous differences based on both firms’ various transactions. However, let us start with a few specific differences. Parent Co.’s investment in Subsidiary Co. has grown from $556,000 to $583,000. This $27,000 increase reflects Parent Co.’s $39,000 share of Subsidiary Co.’s earnings (described above) less the dividend received of $12,000 (80 percent of the $15,000 dividend paid by Subsidiary Co.). Parent Co.’s retained earnings increased from $256,000 to $410,000. This $154,000 increase reflects Parent Co.’s $200,000 profit less the $46,000 dividend it paid to its owners.

Subsidiary Co.’s retained earnings increased from $170,000 to $205,000. This $35,000 increase reflects Subsidiary Co.’s $50,000 profit less the $15,000 dividend it paid to its owners (of which $12,000 was paid to Parent Co.).

Balance Sheet as at January 2, 2017 ($ thousands)

These two Balance Sheets can be placed into a worksheet as follows ($ thousands):

The adjustment process begins as it did at the start of the year. First, Parent Co.’s investment account of $583,000 and then the Subsidiary Co.’s common stock of $500,000 and retained earnings of $205,000 are eliminated. Next, noncontrolling (the Balance Sheet account, not the Income Statement one) is set up at $141,000: this is the subsidiary’s year-end net book value ($1,000,000 – $295,000 = $705,000) times the percentage not owned by Parent Co. (20 percent).

Next, the purchase price discrepancies are set up. PP&E is increased by $12,000, and goodwill is increased by $8,000. PP&E is further adjusted for the increase in accumulated depreciation of $1,000, resulting in a net year-end increase in PP&E of $11,000.

Finally, Parent Co. purchased $40,000 worth of goods from Subsidiary Co. but only paid $28,000 by year end. Thus Parent Co. has a $12,000 payable to Subsidiary Co., which has a $12,000 receivable from Parent Co. Because a firm cannot owe itself anything, all intercompany receivables and payables must be eliminated, so the receivable and payable are reduced by $12,000.

Other Complications

As noted at the start, in reality consolidations is a very detailed process. For example, firms rarely purchase publicly traded firms at one time with one payment. Usually, numerous small purchases are made until the parent owns 5 percent, at which time it must publicly announce its intention to buy more. Even then, it may make many small additional purchases before gaining a majority ownership. For consolidations, each of these small purchases must be tracked and a separate purchase price discrepancy calculated. This is not difficult, but it is detailed. The sheer number of pieces to this puzzle is what makes consolidation an advanced topic for accountants.

The worksheet is now adjusted to look as follows ($ thousands):

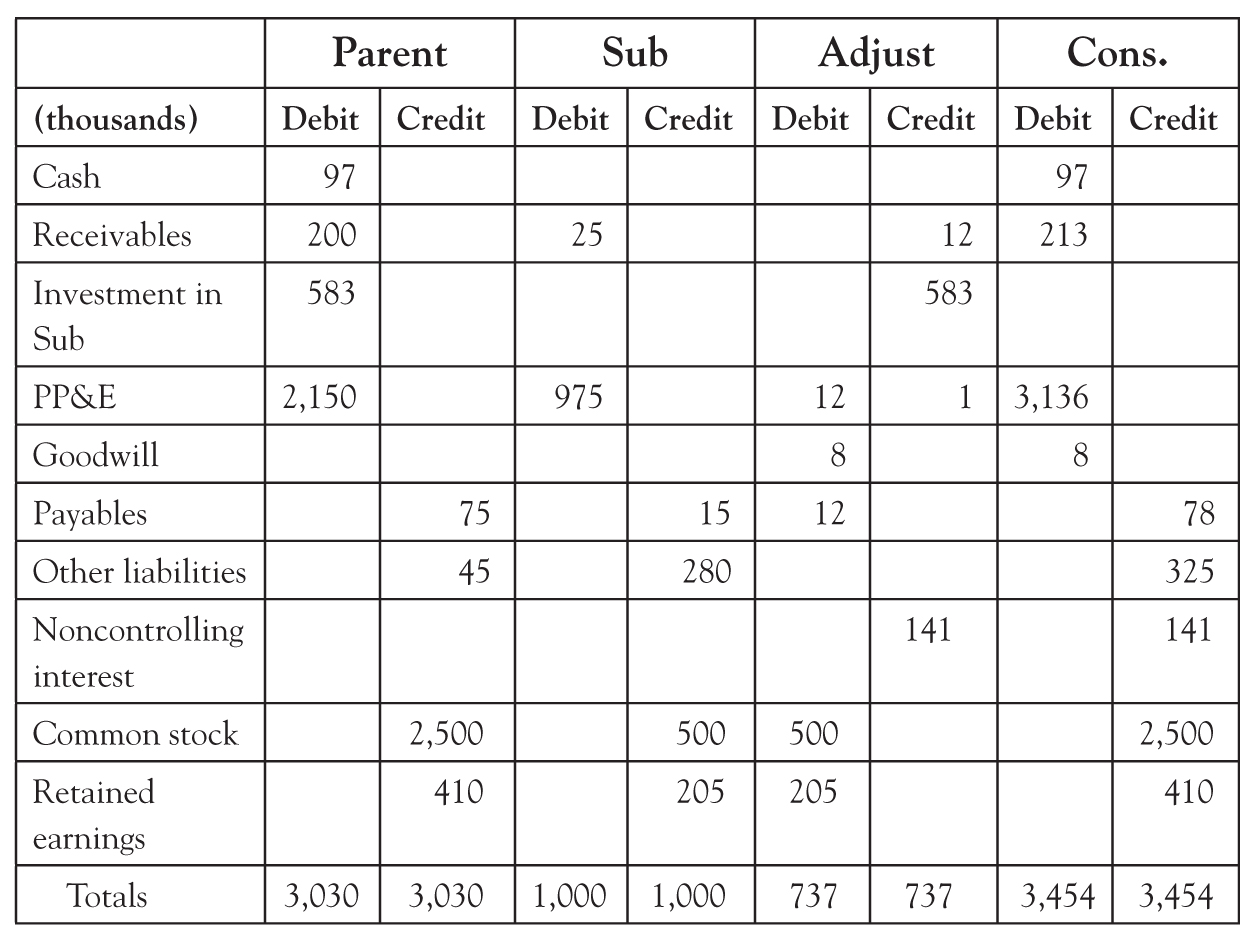

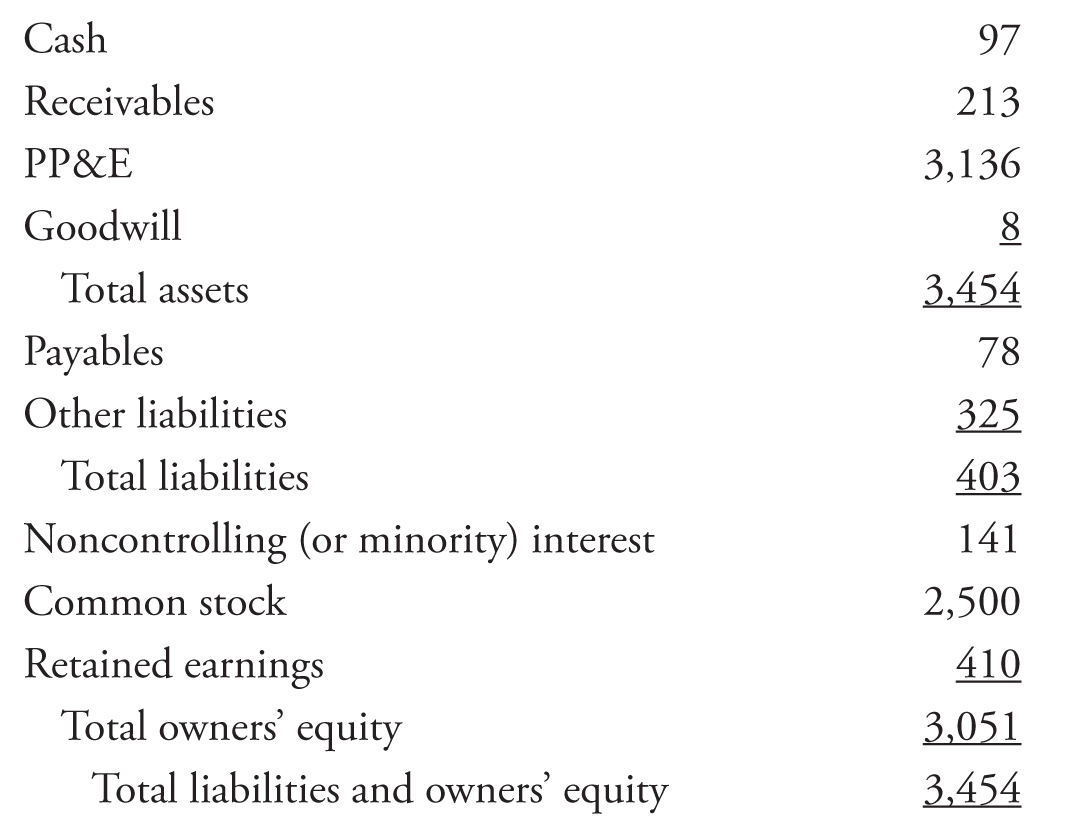

The consolidated year-end Balance Sheet can now be produced:

Parent Co. consolidated Balance Sheet as at January 2, 2017 ($ thousands)

There are several key points the reader should take away from this chapter:

If an investing firm has no control over the dividends paid by the firm in which it is investing, then an investment account is used to record the investment at cost, the investment account is kept at cost, and revenue is only recognized when dividends accrue to the investing firm.

If a firm has some control over dividends and owns less than 50 percent of the voting shares, revenue is recognized, and the investment account is increased (decreased) with the investing company’s share of the subsidiary’s earnings (losses) and reduced by any dividends received from the subsidiary. There are additional adjustments and the final income (or loss) recognized using the equity method will match the one that would be computed if consolidating financial statements were prepared.

Consolidation is a fiction: it represents what two (or more) firms might look like if they were one legal entity. Instead of an investment account, all of the subsidiary’s assets and liabilities, revenues and expenses are included in the parent’s consolidated financial statement after numerous adjustments.

Noncontrolling or minority interest on the Balance Sheet is what the parent does not own in the subsidiary. It is computed as the outside ownership percentage times the subsidiary’s net book (accounting) value of assets less liabilities.

Noncontrolling or minority interest expense on the Income Statement is the outside ownership’s share of the subsidiary’s profits or loss. It is computed as the outside ownership percentage times the subsidiary’s profit (or loss).

A purchase price discrepancy is the difference between what the Parent Co. pays for its ownership in a subsidiary and the subsidiary’s net book value times the ownership percentage.

Goodwill is the portion of the purchase price discrepancy that cannot be attributed to fair market value differences (economic values versus accounting values). Goodwill is reduced if it is determined to have declined in value during the year.

The next chapter examines the time value of money and how it is used in valuation.

_________________

1 A long-term intercorporate investment occurs when one firm buys shares of another.

2 The time value of money and how to compute a net present value is discussed in Chapter 2. Investments are evaluated based on whether or not they provide at least a competitive return, in addition to legal, ethical, and environmental concerns.

3 There is a form of partnership today, which most auditing firms have embraced, called a “limited liability partnership” (LLP). An LLP limits the liabilities of the partners (i.e., the liability of one partner for the negligence of another is limited).

4 A subsidiary is a firm that is owned by another firm. The firm that owns the shares is called the “parent” firm or “holding” firm. Most public firms (and many private firms) are holding companies owning multiple operating firms.

5 More recently, Coca-Cola has purchased a majority and even sole ownership of its bottlers.

6 If only consolidated statements are presented, then the Parent Co.’s statements can use either the cost or equity method. Whether they decide to use one method or the other will not matter because, as shown below, the investment account is eliminated upon consolidation.

7 Dividends never have to be paid until a board of directors declares them and become payable to the shareholders of record on a specific date. If the parent firm owns the shares on the date of record, they are entitled to receive them, which is why this is the date they are recognized.

8 This is similar to the write-down of any long-term asset. The write-down is like a reset and then treated as if it was the original cost.

9 For majority stakes it will not matter whether the cost or equity method is used since, as will be shown in the section on consolidations, the investment under either method is removed from the final presentation.

10 If the dividends were unpaid at year end, then the investing firm would show dividends receivable and reduce the investment account.

11 The word “debit” means to the left (the first column) and the word “credit” means to the right (the second column). Assets are increased with debits whereas liabilities and equity are increased with credits (revenue is increased with credits because it increases equity while expenses are increased with debits). A Balance Sheet not only will have total assets equal to total liabilities plus equity, but the total debits will equal the total credits.

12 For simplicity, the case of just one subsidiary is shown. Two additional columns would be added for each additional subsidiary.

13 As a reminder, assets are increased with debits; liabilities and owners’ equity are increased with credits.

14 One situation where proportional consolidation may be used if a firm owns exactly 50 percent of the voting shares.

15 At one time it was listed after liabilities but before owners’ equity, but accounting norms have changed.

16 Again, in reality there would be numerous adjustments to virtually all assets and liabilities.

17 For simplicity, there is no unrealized intercompany profit, so only the intercompany sales and costs have to be removed. It is sufficient at this point for the reader to simply know that an adjustment is required.

18 The rarely used proportional method would adjust down the 20 percent of Subsidiary Co.’s sales and costs that Parent Co. does not own.