CHAPTER 10

Becoming an Effective Board

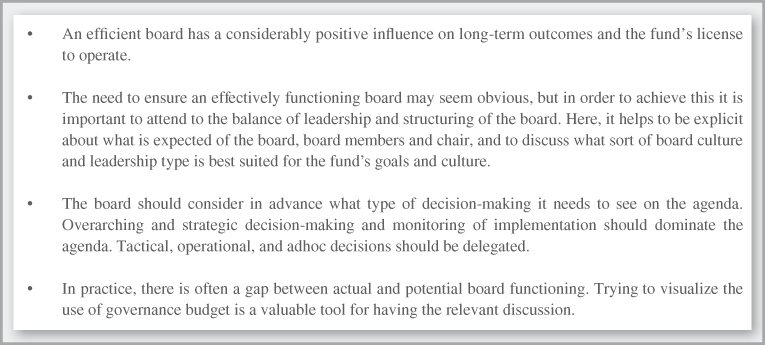

Key Take Aways

This chapter focuses on the board. We start by addressing the tasks of the board and then move on to board composition. We expand on a key concept, the so called “governance budget,” the combination of time, expertise and organizational effectiveness of the decision makers. To a large extent this “budget” determines whether or not your fund will be able to be excel. Following this, we pinpoint the ingredients of an effectively functioning board, which can help identify the strengths and weaknesses of a board. Here we delve into an already-mentioned key concept of this book, which should help in striking the right balance as a board member: “the right altitude—the right distance—the right horizon.” We conclude the chapter by presenting ways to improve the board over time.

RESPONSIBILITIES OF THE BOARD

There are several definitions of a board, but a useful one could be that the board of a pension fund is the instrument to deliver value for its participants1 by providing the best possible financial outcome for the agreed-upon pension deal. The board's responsibilities are described as fiduciary duties. These responsibilities include policy formulation and foresight, strategic thinking, shaping the governance, supervision of management, and accountability.

Board task 1: Policy formulation and foresight has a long-term, external perspective. It answers the question of why the pension fund exists and what it wants to be. It can take the perspective of the stakeholders. It defines long-term objectives and success. In addition, it monitors the (large) external forces of change and how they may affect the fund.

The framework is the formulation of the mission, goals and objectives, beliefs, and the way they take shape both in the present and in the future. The board should actively own these topics. A mission tends to be timeless and universal: the Dutch health care pension fund PFZW's goal is “to provide a good and affordable pension to all the workers in the health care sector” while the Norway Fund aims “to build and safeguard financial wealth for future generations.”2

Policy formulation looks many years ahead, with a horizon of 10 years not being unusual given the cycles in the capital markets. This leads to different long-term scenarios. By recognizing the role of uncertainty and exploring the sources of turbulence and uncertainty, the goal is to iteratively and interactively generate new knowledge and insights to help the pension fund assess its circumstances and enable adjustments in strategy.

Board task 2: Strategic thinking shifts the focus of the board from an external to an internal perspective. If the fund knows what success means given its mission and objectives and current and expected future context, how does it become fit for purpose to achieve that success? This translates into a set of strategic questions:

- How will it organize its investment process?

- Which competencies does it need?

- How does it regard its strengths and weaknesses from this perspective and what should it do about them?

- What can it outsource and to whom?

- Is the board itself equipped to take on future challenges?

This exercise looks two to four years ahead and leads to measurable goals. It should be about concrete outcomes (e.g. does passive investing make sense in the current environment) as well as about soft outcome factors (e.g. if there is no learning culture in the investment management organization [IMO] or pension fund, it will never be able to adapt to fast-changing geopolitical developments).

So here, the key question is how to translate the mission and purpose into strategy in an effective and efficient way. This often demands a shared understanding of roles and responsibilities: the board should direct, while the executive should manage. At the same time, it requires a subtle interplay between the board and the IMO: the board needs all the relevant information to be able to make the right strategic choices, while the IMO needs clear guidance from the board in order to translate strategic choices into implementable actions. So, the board should concentrate on the “what” and the executive on the “how.”

Board task 3: Shaping the governance. Mission, purpose, and strategy differ from one pension fund to another, making a “one-size-fits all” governance structure challenging for a board of trustees. A key issue for the board is therefore to determine how it will apply strategic principles. Sound corporate governance policies and practices towards staff, investment organization, and other stakeholders should foster shared understanding and a common purpose consisting of achieving the fund's goals.

The investment governance framework should clearly set out the roles and responsibilities of both the board and other fiduciaries such as the investment managers and consultants. It should be explicit about the choices and assumptions made in the investment framework, including key performance indicators (KPIs) for the investment choices so that they can be evaluated, challenged and, where necessary, adapted.

The framework should also identify governance issues that need to be elevated from the subsidiary to the board, or which require the approval of the board. Effective two-way communication between the board and the stakeholders is also important; therefore, the framework should set out how and when issues should be communicated. Finally, the board should periodically revisit its investment governance structures to ensure that they remain appropriate. Changes in operating and regulatory conditions may also necessitate changes.

Board task 4: Supervision of management is the board's monitoring of the total fund and organizational performance—keeping the organization under prudent control. Here lies the essence of the board's supervision of the investment management that is delegated to an IMO. Has it delivered investment outcomes that are good enough, given the circumstances? Is it fit for purpose moving forward? Monitoring involves the use of feedback to manage ongoing exposure to investment opportunities so that the pension fund's objectives and constraints continue to be satisfied and remain achievable looking ahead. Various aspects are monitored by the board:

- Is there an implicit or explicit change in the pension fund's risk profile and objectives?

- Do the assumptions with regard to economic and market input factors still hold?

- Is the current portfolio within the rebalancing guidelines?

- Are the managers chosen to reflect investment styles consistent with the expected return/risk profile, investment beliefs outlined in the strategic plan, and other key factors?

The board has to decide whom to delegate these monitoring questions to, for example to the IMO, executive staff, or investment committee. It also needs to be clear about how the monitoring process should evolve: which choices should the board make, and what elements are best left to the other bodies of the pension fund? Boards clarify these fiduciary responsibilities by developing detailed reviews of their decision rights framework, with a focus on investment and risk management decisions. A formal approach, such as the RACI framework (Recommend, Approve, Consult and Inform) shown in Exhibit 10.1, is extremely helpful not only in clarifying the different roles and responsibilities, but also in allowing for a debate and review of these decision rights.3

EXHIBIT 10.1 Example of a decision right framework for the supervision of investment management.

Another important reason to clarify investment and risk management decisions as part of the investment management framework is that it helps in developing the right reporting, which is key to effective supervision of policy, and monitoring of investment management. Reporting provides the board with the right key objectives in monitoring and aids them in making the right decision. Every report should be factual and based on verified information. The board should not have to question or doubt the quality of the data, and the report should be free from errors and duplication.

An increasingly important part of reporting is the responsibility that the board has to monitor environmental, social and governance (ESG) decisions integrally in the investment management process. Their purview includes topics such as the development and maintenance of proxy voting guidelines. In addition, as ESG integration becomes an increasingly common practice in asset management and pension funds are more often combining activities to address climate change and other environmental and social issues (Climate Action 100+ initiative, Access to Medicine), boards include the monitoring of these activities in their reporting and communication with the beneficiaries.

Board task 5: Accountability. The board has to be accountable to the most important stakeholders and to society at large about everything it does and the results of its actions. The board is accountable to the pension plan members and beneficiaries, its supervisory body (where relevant), and the competent authorities. Accountability to plan members and beneficiaries can be promoted by appointing members of the governing body who are pension plan members, beneficiaries, or members of their representative organizations.

The breadth of accountability varies between the different legal systems and cultures around the world. Accountability will develop over time, and individual institutions can choose between levels of accountability.

Because many different individuals and parties in and around a pension fund contribute in many ways to decisions and policies, it could be difficult to identify who should be accountable for the results. This is known as the problem of many hands.4 It creates a dilemma over accountability within the pension fund organization. If individuals are held accountable, those who had no role to play in the outcomes of a decision are either unfairly punished, or they “take responsibility” in a symbolic ritual without actually suffering any consequences. For pension funds, the accountability ultimately rests with the board, which has to accept its consequences.

In other words, a board should never undertake any action for which it cannot be accountable. This seems obvious, but it is not necessarily. For example, what if a board agrees to the administration of a pension plan that can only be realized via relatively high investment returns? The board then unwittingly assumes accountability for results caused by factors that are not under their control.

BOARD COMPOSITION

Boards of pension fund plans direct and control implementation, but do not manage it. Boards have the task of defining the purpose of the pension fund and agreeing on a strategy for achieving that purpose. They are responsible for appointing executives to turn strategic plans into action, for supporting and counselling them and, if necessary, for replacing them. Above all, boards are there to provide leadership, and it is in that context that the composition of the board should be considered.5

However, the distinction between direction and control (i.e. strategy), and implementation is not always clear, nor is it, for smaller pension funds, a practical one to make. For example, board members can be involved in several steps of the selection process of managers, preparing mandate searches in consultation with an advisor, or deciding on the criteria, for example. Is this strategy, or implementation? At the very minimum, trustees set strategic goals and objectives for the selection process and leave the other steps to the advisor and pension staff.

A single board at the head of a pension fund is the most common board structure. Unitary boards of this type are made up of executive and non-executive board members. Contrastingly, two-tier boards separate these two roles. A pension fund board can have anywhere between 5 and 15 members. A generally accepted view is that boards should not be excessively large; 7 or 8 is often considered to be the ideal number of board members. A pension fund has to strike the right balance. If the number is too low, the board will not have sufficient competency to perform its tasks, nor be considered sufficiently representative by the participants if representation is an important part of the board profile. On the other hand, overly large boards will influence performance negatively, for example by creating inertia when decisive action is needed moments of urgency, such as during financial crises.

A board comprises board members, and individuals supporting the board. Board members are a chairman, and executive and non-executive board members. Their roles can be defined as follows:

- Chairman. Their role is to manage the meeting, aiming to distinguish between debate and decision-making, and ensuring that decisions that are consistent and executable are made. The chair can have different styles for fulfilling this role, each with its own influence on decision-making.

- Executive board members (also called executive director). Members of the board of the pension fund who also have specific management responsibilities, managing a part or the whole staffed office or IMO.

- Non-executive board members (also called non-executive director). Board members without responsibilities for the daily management or operations of the pension fund. The legal duties, responsibilities, and liabilities are the same for both executive and non-executive board members. Both have a fiduciary duty to the pension fund and must act in the best interests of the company. Pension funds can select independent non-executive board members, or non-executive board members who are employed by the sponsor or affiliated to the sponsor companies. Funds make their own choice herein, whereby the background and company culture of the affiliated companies or the sponsor play a role more important than would seem to be the case at first glance. The presence of expert board members from the company or sector is a good, transparent manner of ensuring the company culture is visible. These board members are not only considered to know “what is going on” but can also be addressed directly in the company on the consequences of the decisions and they are aware of this when making decisions. On the other hand, independent (non-expert) non-executive board members bring in outside experience and best practices from other pension funds or industries. Independent non-executive board members, especially if this is their full-time occupation, will be more mindful of reputational risk as this might affect their careers more directly than other board members, focusing on managing risks and creating more stability in outcomes where possible.6 These different expectations and added values from the non-executive board members should be reflected in the job specification for the selection process.

Roles That Support the Board

- Secretary. The secretary supports the chair in setting the agenda and provides documents and materials beforehand to assist the decision-making process. Ensures that complete, timely, relevant, accurate, honest, and accessible information is placed before the board to enable directors to reach an informed decision. Decides with the chair what should be delegated to the staff or executive board members, and checks whether a document supports the right step in the decision-making process. The secretary's task is this to identify the decision needed, generate solutions and alternatives, decide on an alternative, and implement and evaluate the chosen solution). Minutes support the board meeting, providing a consistent record of how decisions have been made, why the board made them, and what arguments supported the decisions.

- Board advisors. They do not have a formal role in decision-making but can certainly influence the discussions. With smaller funds, the actuary is one of the regular attendees, as they are able to cover the pension deal as well as provide expertise in asset liability management. Alternatively, the investment consultant could attend, as they possess knowledge about the investment plan, process, and implementation.

WHAT IS EXPECTED FROM BOARD MEMBERS?

The importance of the competences and knowledge that a board member must have is widely accepted, but what competences and knowledge are actually expected? Huse,7 a governance researcher, lists seven different elements:

- Pension fund specific knowledge about the functions, organization, regulation, and pension product. Often, this knowledge has been acquired through board memberships at other pension funds, or previous roles close to the pension fund (staff, consultant). The board member is aware of the strengths and weaknesses of the fund, its strategic challenges, and its bargaining power in the market.

- A board member may bring in function-oriented competence, such as finance, accounting, strategy, or general management experience. This type of knowledge is particularly important for the advisory tasks of the board. Sought-after skills in pension board members include knowledge of, and experience in, risk management, institutional investments or actual portfolio management, especially if this mirrors the differentiating choices in the pension fund's investment strategy. For example, this might be experience with illiquid assets if the fund has a large allocation to infrastructure, or derivatives if the fund runs an extensive hedging program.

- Process-oriented competences include knowledge about how a good board functions and how it should be run. Due to the professionalization of boards, there are a growing number of people seeking to make their living from board memberships. These board members have specialized knowledge about the tasks of boards and the way they work.

- Relational competences shift the focus to the stakeholders of the fund; this kind of competence is related to building relationships with and acquiring influence on important stakeholders outside the pension funds, for example, influence with regulators, political groups, or financial institutions. Communication with internal actors is also very important here.

- The fifth competence is related to the personalities and personal traits of the pension fund board members. This includes the ability to think creatively, think analytically, think critically, have the courage to address any elephant in the room, and also the ability to generate cohesion.

- Board members need negotiation skills, as they represent the fund and have to manage and monitor the stakeholders involved in executing the pension plan. Board members need to influence or shape the decision-making in such a way that it meets the interests of their participants. Negotiation skills therefore have a link with integrity—board members need to be aware of why they are in that position, namely to take care of the interests of the participants. This could lead to a member taking an independent standpoint and not being overly involved and aligned with either the board or the investment organization.

- Finally, “ownership,” or taking personal responsibility for the task, is considered to be the ultimate qualification competence for being a pension fund board member. Board members who ensure that strategy is developed executed and monitored, also ensuring transparency to other stakeholders and embedding the proper checks to make sure that the pension fund develops in a sound way.

What Is Expected of the Chair?

The chair is crucial to the board. The most visible role played by the chair is to govern the workings of the board, including directing its meetings, making sure that decisions are made, and acting as conciliator when elements of the board differ—although the chair is obliged to play this role with moderation and not to bias the outcome of the meetings towards any special agenda.

The core functions of the chair are to provide effective board leadership, be a team leader, and ensure that the characteristics of an effective team are present. These core functions include setting the agenda, presiding at the meeting, and developing the board and board culture, which provides the context for the board functions.8,9 Better than anyone else, the chair is the person who can and should make sure that the board maintains the right altitude, distance and horizon in relation to the investments.

In most cases, the board will delegate tasks or advisory functions to a number of board committees, one of which will be the investment committee. The chair has an important role in overseeing and, when necessary, improving the functioning of these committees. The core functions of the chair can be broken down as follows:

Setting the Agenda, Presiding Over Meetings

- Setting the ethical tone for the board and the pension fund. The chair embodies and strongly promotes the values that the board aims to develop (see Chapter 3).

- Providing overall leadership for the board.

- Formulating (with the chief executive officer [CEO] of the staff, the investment organization, and the secretary) the yearly work plan for the board based on agreed objectives and playing an active part in setting the agenda for board meetings.

- Upholding rigorous standards of preparation for meetings, ensuring that complete, timely, relevant, accurate, honest, and accessible information is placed before the board to enable members to reach an informed decision.

- Presiding over board meetings and ensuring that time in meetings is used productively.

- Ensuring that decisions made by the board are executed.

Developing the Board and Board Culture

- Participating in the selection of board members (via a nomination committee), and overseeing a formal succession plan for the board, the staff and other senior management appointments within the pension fund.

- Acting as the link between the board and staff, and between the board and the CEO of the IMO.

- Ensuring that good relations are maintained with the fund's major shareholdings (such as the IMO) and its strategic stakeholders (notably the sponsor).

- Making sure that all board members are aware of their responsibilities through a tailored introduction program, and by ensuring that a formal program of continuing professional education is adopted at board level.

- Managing conflicts of interest, making sure that these are made transparent in roles and decision-making, and creating a culture where conflicts of interests can be discussed openly.

- Monitoring how the board works together and how individual board members perform and interact at meetings. Ensuring that members play a full and constructive role in the affairs of the company. The chair also takes a leading role in the process of removing non-performing or unsuitable directors from the board.

It is obvious from this list of tasks that the personality of the chair will play an important role. The board chair not only sets the tone for board meetings, but also for how engaged board members are and how they view the added value or effectiveness of their role. When choosing a chair, the selection committee should be aware of the personality types among board chairs. Many persons embody a combination of types and can easily switch depending on the context, but many do have preferred styles.10

Things to keep in mind when choosing a chair are: (i) that one should not expect the chair to be a superhero and (ii) it is worthwhile to carefully describe the traits expected from a chair and select people who come as close to the ideal as possible: the consequences of not selecting the right chair can be very costly and can have long-term implications for the fund.

APPOINTING NEW BOARD MEMBERS11

The market for board members is opaque; there is no clear supply and demand. Despite whatever policies are in place, new board members have traditionally been selected from the existing board's professional networks. For pension funds, this means that people regularly switch posts throughout their professional careers, generally from pension fund staff or IMO to the board. For non-executive board members, the network is somewhat wider. Usually, there are limited considerations regarding the qualifications required, and selections often take place without an assessment of the present and future needs of the boards. This is especially true in countries where the remuneration of board members is relatively low given the (legal) liabilities that the board is exposed to compared to similar board roles in other sectors. Therefore, boards are often content with finding a candidate who is actually willing to join. Changes in boards are often incremental, and the selection of a new board member usually takes place after an existing board member withdraws for some reason.

However, more objective and rational selection processes are increasingly taking place. These processes include an assessment of the needs of the pension fund, how these translate to a desired profile for the board member, and an extensive search to consider a larger set of candidates than just in the existing professional network. Creating nomination committees is an increasingly common selection mechanism.

An average pension fund with a board of six to eight members will select one or two new members each year. Given increasing expectations placed upon boards, new board members must be prepared to contribute rapidly. The questions, points of attention, and concerns they have about whether becoming part of the board is a good plan for them fall into different areas:12

- Can I commit myself? Given the demands of board term—20–30 days a year for up to nine or more years—it pays to carefully weigh the advantages and disadvantages of a board appointment carefully. The key question is whether joining the board it is mutually beneficial—on the one hand that the prospective trustee finds it engaging and useful as a growth opportunity, and on the other hand that they can also add a valuable perspective to the pension fund board. It is, therefore, important to obtain a good view of the board calendar and activities—not just what the next board meeting will be about, but the key processes of the board over the course of 12 months of board meetings.

- Does it strengthen my network, and can I deploy my own network for the fund? Other considerations may be who else is on the board—in particular, a point of interest is whether the position offers the opportunity to work with a good chair and gain exposure to experienced executives from pension funds from other industries—the strength and diversity of the executive trustees and/or staff, and how well the board works together.

- Getting to understand the fund. As part of your due diligence, read published information about the pension fund. Take a fresh approach; although pension funds seem quite similar due to the pension deal, investment model, and organization, the flow of the fund might be quite different. What many don't appreciate before they've actually done it is just how much pre-reading material there can be, and the amount of time it can take to digest it thoroughly. Focus on the KPIs and lead indicators for the pension fund. What do you as a trustee keep an eye on? Every other question ends up stemming from those KPIs.

- Is the fund aware of its challenges? Understand how the board views sector and pension fund risk. How does management assess, present, and articulate risk? Are assumptions discussed and challenged clearly and freely? New trustees should not be afraid to ask for the process to be tailored to their needs if they want to explore certain areas of the business in greater depth.

- What are my fellow trustees' priorities? One-on-one meetings with as many other trustees as possible prior to the first board meeting can provide a sense of the priorities of the board, as well as the dynamics among trustees and between staff and the board. The time a new trustee may take to meet people upfront definitely pays off in the long run because they get context they otherwise wouldn't have got. Getting a read from other trustees about the board's priorities for example can provide important context, as can do using meeting breaks to follow up on your questions.

- New trustees can and should be involved from the beginning: it will be more helpful to listen than to talk at board meetings, but they should be willing to participate in the discussion, especially in their own area of expertise.

- Raising questions. By definition, a new trustee lacks perspective on the board's history—the sacred cows, the topics that have been debated at length, and other important contexts. This makes knowing when to raise questions or to push for more information all the more difficult. Fresh eyes are good, but one of the worst things a new trustee can do is walk into the boardroom and raise topics that aren't going to be productive and which the board has already discussed at length. That is why it is important at least to have read the board minutes, if not the papers, for the previous year or so, so new trustees can understand some of the key issues and debates.

GOVERNANCE BUDGET OF THE BOARD

The governance budget of the board is crucial for the type of investment model and implementation that the fund is to pursue. Urwin, a researcher and investment advisor, defines the governance budget as the combination of time, expertise and organizational effectiveness of the decision makers.13 Three types of governance budget can be identified:

- Cost minimizing budget. This budget is compatible with the lowest governance resources and is a set of arrangements that manages down all costs and focuses on easily attainable investment returns. Being the least sophisticated investment strategy, it would hold only mutual funds or bonds and equities, and use mainly passive managers and mutual funds.

- Exploitation budget. With a greater governance budget available, the fund can pursue more value creation opportunities, but within the existing investment set known to trustees. The focus would be on improving diversity of market exposure outside equities and bonds and adding private market forms of equities and bonds as well as alternative assets like real estate and infrastructure. These assets are considered “tested and proven,” and the fund can draw on what is considered common knowledge about these assets. Generally, the portfolio construction will not contain much exposure to active management. Alpha is the hardest part of the investment spectrum to create value with, and also involves more detailed reports and accountability, decomposing the active investment returns.

- Exploration and Exploitation budget. The board will further expand resources to enhance diversification but will also include a significant number of resources embedding risk in the overall value chain of the pension fund. There is greater emphasis on selecting manager skills, including when manager skills and market returns are difficult to separate. New strategies and asset classes are sought out, under the assumption that first mover advantages will translate into a higher return that offsets the extra costs of sourcing, risk management, and pioneering to develop the asset into an investable product.

A question we can then ask, is whether there is a way to quantify the governance budget, compare the actual use of the budget with what is required, and take action as a board to close that gap. Surely, a board that spends only one session per year on investment strategy, evaluating the results and setting out the course for coming years will be deemed to be severely “under-spending” the budget. The board is then much too detached to know what is going on. The governance budget of a board is shown by Exhibit 10.2.

EXHIBIT 10.2 The governance budget of a board.

As a simple exercise, consider a board that has allocated its governance budget equally, covering topics such as pension administration, communication, investments, internal organization, and overall accountability. Each topic demands 20% of the time and resources of the board. To continue the exercise, consider your own fund, add 5% for each choice that is more demanding, and subtract 5% for each choice that is less demanding. What is the overall score? For many funds, due to one or more of such choices, the governance budget is overstretched, leading to investments not claiming 20% but between 30% and 40%. The usefulness of this analysis lies in highlighting how the board uses its time and resources, and also in providing an informed basis for addressing this issue: should the board expand the number of meetings (relieving the pressure on the agenda, but not a long-term solution), delegate more to committees and staff (raising the question of what can be effectively delegated without losing one's grip on overall responsibilities), or simplify the investment processes (raising the question of which choices can be altered without affecting the achievement of the fund's goals).

BOARD DECISION-MAKING CULTURE

The performance of the board is determined by three types of decisions: comprehensive decision-making, strategic decision-making, and ad hoc decision-making.14 The board avoids tactical decision-making, and delegates operational decision-making, monitoring, and oversight as much as possible. We further explain these three types of decision-making.

- Comprehensive decision-making. This is about establishing the purpose, mission, and vision of the pension fund. External stakeholders play an important role here, especially the sponsors and participants of the fund. This type of decision-making is infrequent; reviews or updates will be carried out when the pension deal is renewed, or when circumstances require a critical review of the pension fund's raison d'être. In developing overarching decision-making, the board is challenged to view the pension fund from the ground up, focusing on its functions: what functions are needed to best fulfil the pension deal; is a pension fund actually the best way to realize this; and is this pension fund's approach the best possible one?

- Strategic decision-making. Here, the board decides on the investment beliefs and investment model best suited for realizing the financial objectives of the pension deal. Next, the parameters that the investment organization needs to implement this policy are set out in the investment policy (capital market expectations, asset allocation, and investment styles). The asset allocation choice is traditionally considered to be one of the key choices made by a board. For its decision-making, the board needs to use research-based information (which choices have been proven to work, and how robust can this be in the near future), information from peers (similarly, which choices have been proven to work in practice), and information about financial markets (what, if anything, can be said about future risk premiums given the current state of the financial markets).

- Ad hoc decision-making. This refers to unanticipated developments in the pension fund and financial markets that fall outside the scope of the strategic framework of the pension fund, alter fundamental assumptions made during strategic decision, and cannot wait to be dealt with in the planning cycle. For example, the investment plan might have included expanding into private equity as a new asset category, but despite previous thorough analysis, new information comes to light suggesting that the expected return will be below the expected hurdle rate set in the investment plan after all. A development could also go in the opposite direction, for example, if the board has established conditions for when to start a particular investment and these conditions are now met, meaning that the investment can go ahead. These types of decisions do not follow the planning cycle of a pension fund as written down in the calendar, but still need to be addressed. Managing through a financial crisis on the other hand is not ad hoc decision-making. As will be discussed in Chapter 14 the choices, impact, and response during a financial crisis can easily be pre-envisaged by a board and should therefore be part of the strategic framework.

- Oversight decision-making. The pension fund monitors the implementation of its strategic framework, involving two types of decisions. First, are we doing things right? The board makes sure that it has an effective mechanism in place to perform these monitoring responsibilities. This will enable it to ensure that all choices have been compliant with the established investment framework. Non-compliant events can be reviewed to see if they have anything in common, and whether this should lead to changes in the monitoring framework. Secondly, the board reviews the monitoring results in order to challenge the goals and assumptions of its own strategic framework: Are we still doing the right things? Are we able to realize our goals? What changes—if any—should be made in order to keep on realizing these goals? If any questions are answered in the negative, how should the board review and adjust its strategic or overarching framework?

In pension governance, a board separates strategic board roles and responsibilities from implementation and execution. Implementation and execution decisions are time-consuming and require specific expertise, and any single decision does not warrant a discussion by the board or alter the outcome in relation to the pension fund's goals. The strategic framework, however, does, and is thus firmly placed on the board agenda. Therefore what is not part of the board's decision-making is as follows:

- Tactical decision-making. Tactical asset allocations are changes in the portfolio to anticipate changes in financial markets, requiring predictive knowledge and proactive action. Boards are the representatives of asset owners, not asset managers. Setting aside the lackluster results of many tactical choices, boards do not have the knowledge to time the market cycle.

- Operational decision-making. This refers to the decisions needed to maintain the pension fund's operational processes, ranging from cash flow management, rebalancing, and collateral management to drawing up reports. These types of decisions are either delegated to an executive board member or to the staff of the pension fund. The board provides resources to facilitate operational decision-making and does not micromanage.

- Monitoring and oversight. This is about ensuring compliance with the stated objectives of the pension fund on different levels overall, but also on an individual manager level. This entails reviewing investment management agreements, analyzing performance reports, and setting up an integral compliance framework. The board delegates this to an executive board member or to the staff of the pension fund.

SUPPORTING THE BOARD: EXECUTIVE OFFICE AND STAFF

The board of trustees is supported in its work by a staff or executive office. Larger pension funds are able to set up their own organization and hire staff; smaller pension funds ask an investment consultant, actuary or other professional to provide this support. Giving a clear and decisive mandate to the executive office enables the board of trustees to focus its attention on the strategic challenges that the pension fund faces.

The executive office prepares the basis for the board and the committee's decision-making, is a sparring partner for them, and acts on behalf of the board both as a client of, and a fixed contact point for, the administrative organization. The executive office:

- Supports the board in organizing and servicing meetings of the board and its committees;

- Provides a focal point for the chair of the board to promote controlled, efficient, and effective management;

- Sets priorities and manages internal decision-making;

- Monitors the execution of the board's decisions, and reports back on this to the board and its committees;

- Provides the first point of contact with regulators, participants, journalists, etc.;

- Carries out reviews and analyses of policy issues relating to the plan design.

There is another function that is often not made explicit: the personnel in the executive office will often have been there longer than the individual board members, who in a certain sense are passers-by. This means that they have an important but subtle role in board member education and safeguarding the long-term direction of the fund.

In recent decades, executive offices have increased in importance for several interrelated reasons, often borne out of necessity.15 A dominant trend in the 1990s was that pension funds spun off their investment activities or pension delivery organization. A strong motivation for doing so was economies of scale: pension funds with internal IMOs found it increasingly difficult to keep up with the increased investments in IT, compliance and risk management, while on the other hand there was constant pressure to reduce costs. Spinning off the investment organizations introduced new opportunities and challenges. First, the board had to develop its own policy and monitor capabilities after spinning off investment organization, introducing the need for a separate staff to support the board in these questions.

Besides the economic rationale for spinning off investment activities, boards were increasingly prompted to adopt insights from other sectors' management theories. A dominant theme was (and still is) to separate policy and implementation and focus on the “core” responsibilities of trustees. Core responsibility is, intuitively, developing the investment framework and realizing the investment returns needed to fulfill the pension promise. Executive offices also play an important role as “interface,” monitoring the investment managers and making sure that this implementation is done according to the mandate set. The executive office staff is usually highly specialized and skilled. They understand the investment management side but are able to filter and condense the technical discussions in such a way that the strategic issues are made clear to the board, and that technical details do not overburden the board's agenda. Exhibit 10.3 lists the characteristics of an executive office.

EXHIBIT 10.3 Characteristics of an executive office.17

There exists a wide range of executive office organizations. The board can decide on a clear separation of the roles of board chair and CEO. The chair is responsible for leading the board, and the CEO for leading management and the executive office.16 The board appoints the CEO. Exhibit 10.4 shows the possible configurations, starting with models where the executive office is at most coordinating. The next options show how these offices can be an effective interface between board strategy on the one hand, and implementation on the other hand. However, the challenge for a board is to ensure that the executive office remains aligned to the fund's goals. That is, there is a risk of the tail wagging the dog. If the office extends too much, the board runs the risk of shifting its countervailing power between the board and the investment organization to the board vs. the executive office. This means it will become too distant and hands-off to have an impact.

EXHIBIT 10.4 Possible models of a fund's internal organization.

INGREDIENTS OF AN EFFECTIVE BOARD18

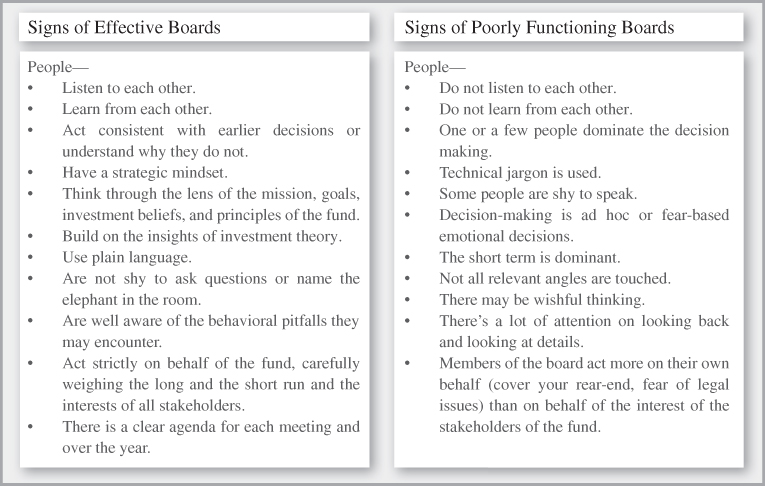

The need to ensure that a board functions effectively may seem obvious, but in order to achieve this, it is important to attend to the balance of leadership and the structure of the board. The structure of the board will also exert the biggest influence on how corporate governance is practiced on an ongoing basis. Creating and maintaining an effective board is hard work. We recapitulate the debates in this section, and end with a list of poor and effective characteristics of boards (Exhibit 10.5).

EXHIBIT 10.5 Characteristics of poorly functioning and effective boards.

People and Board Composition

Individually, board members should at least have a working knowledge of all the topics that are handled in this book, so that they are conscious of all the relevant angles. As a group, they should be diverse in terms of competencies. In a good board, the sum is a lot larger than the individual parts. This means that the individuals also need the necessary skills to work (well) together. Not every personality type is fit for this role. Often we see that one person or a small group of people are dominant in a board, typically the chairman or a group of experts. The role of the chairman is important in building and maintaining a board that functions well. The board also needs to be aware of the main behavioral pitfalls that often lead to poor investment decision-making.

Process

In order to make sure that the board works well on all the relevant angles and topics, it needs an agenda that covers all the topics. To enforce and be well-prepared for this, once again the chairman and the secretary of the board are key. Most board members will have a limited number of hours available, so the board has to make good use of this time. Too often time is not really budgeted for what really matters, with the risk of putting the “urgent” ahead of the “important.”

Perspective

The board needs to spend time on policy formulation and foresight, strategic thinking, supervision of management, and accountability. It is essential to have an outside-in perspective, as it is easy for a board to become complacent. Are you really doing the best possible job for your stakeholders? Do you understand them? Does the fund know what its peers are doing and why? These are the questions that need to consistently be asked.

The Right Altitude, Horizon and Distance

There are three perspective issues for the board, namely:

- Altitude. Does the board look at the total fund setup and its outcomes from a helicopter perspective? Can it achieve a critical distance towards itself?

- Horizon. Has the board organized itself in such a way that it can look forward and backward over a period of at least 5–10 years? Even if that time span is longer than the individual's time span as a member of the board?

- Distance. Is the board able to maintain the right distance from the execution of the investment management—is it close enough to be able to fully carry out its responsibility, yet not so close that it is taking operational decisions that should be taken by the executive?

Power and Delegation

The board should take full responsibility for the process and outcomes, and not hide behind experts. Board members cannot hide behind such comments as “apparently, this is the way they do things over here” or “I do not have the power (or expertise) to judge or change things around here.” If they feel that way (especially after reading this book!), they should not be a board member. Boards will have to delegate a lot of matters to others such as board committees or external parties—fiduciary and IMOs for example. More and more often there is an executive bureau between the fund and the outside and internal parties. All this delegation can provide specialization and potentially add value in the investment process, but it will also produce principal–agency issues (see Chapter 2) that can increase the implementation gap and drag down results. Boards will hire “experts” or expert organizations, and managing experts is extremely difficult. They tend to have narrow and not holistic expertise, and they are sometimes in love with their own expertise. Therefore, the board should have serious counterbalancing power, and have a clear idea of what this counterbalancing power means in practice (e.g. more checks and monitoring, an executive board member from a similar organization on board, etc.).

Creating the right interaction between the board and the “executive organization” is challenging. Normally, in length of stay, time budget, expertise, sheer number of people, and often in pay check, the IMO is much stronger than the board. In this situation, it is very easy to let the “experts” dominate all the relevant discussions, including the core responsibilities such as the mission, beliefs, and policy. If this is the case, the board is taken hostage by the executive organization. We'll address this important topic in a few chapters.

Learning

Finally, the key difference between an “OK” functioning board and an excellent board is whether or not it is a learning board. In other words, learning becomes part of the day job of boards and is not stacked on top of an already heavy agenda.