4.4 What is a Healthy Habit to Implement Improvements?

In a complex environment, improvements can’t be planned or budgeted.

Improvements are explored step by step.

Introduction Questions

1. How are strategic improvements implemented in your organization?

2. Which strategic improvements are so complex and unpredictable that they cannot be planned?

Enabling Improvements

The agile leader is responsible for adapting and improving the environment of the self-managing teams so the teams can grow. Teams have the natural tendency to grow like crops in a field. When crops don’t grow well, the farmer adapts the environment until the crops thrive.

After implementing the tools already described, the teams have an inspirational direction; they take ownership over the products and services, and they learn quickly from users to continuously improve. But how can the agile leader improve the continuous-improvement culture? Without this culture, the current level of performance is likely to be ingrained while the world around is accelerating. These two don’t match. The leader can (traditionally) decide to push the teams and set ambitious targets, but that’s not improving the culture either. The leader can just wait for his teams to step up and improve, but what if that takes too long or just isn’t good enough? How can the leader use the culture of self-managing teams?

It would be even greater if this also would give a certain level of control over the improvement, making it clear where we currently are with the improvement and what is likely to be done next.

How do teams learn from each other? Self-managing teams don’t learn through a fixed, up-front program. That’s too traditional but also fundamentally impossible because the new improvement has yet to be explored and unveiled. There is no map or quick solution to find these improvements. These teams learn through social learning. And big change and improvements go viral. There are three basic ingredients needed to drive viral change. They are partly derived from the work of Leandro Herrero.3

3. https://leandroherrero.com/the-key-viral-change-principles/

A relatively small group of people can have a great power in the creation of change.

The formal leaders and structure have to support this small group of change enablers.

The first steps of change should be quickly beneficial and rewarding.

Over the past years, millions of people have quickly adapted their behavior and copied the behavior of others. From Angry Birds and Pokémon GO to Facebook and the use of smartphones for things other than calling somebody—most of them have these three basic ingredients ingrained in their success.

Relatively Small Group

The small group that has great power in the creation of change first includes the few people who initiated the idea. For Angry Birds, the characters and game concept were created by a man named Jaakko Iisalo from Finland.4 Together with a small group of people, he worked on the prototype and launched the first game. Now millions of people play the game on a daily basis. Pokémon GO was launched in 2016, and the team of builders had great power in the creation of change: as of May 2018, the game had been downloaded over 800 million times.5

4. https://www.theguardian.com/artanddesign/2016/feb/23/how-we-made-angry-birds

5. https://www.pocketgamer.biz/news/68209/pokemon-go-captures-800-million-downloads/

Support

The success of Angry Birds and Facebook are made possible thanks to a lot of things, from mobile internet infrastructure to all the technologies needed in the smartphones. Thirty years ago, these changes were impossible because there was no underlying support.

First Steps

Games like Pokémon GO and apps like Facebook purposefully design the gameplay and ease of use, respectively, within the first few minutes. The first levels of Angry Birds are very easy, and the user feels like he can do it. Netflix states that users should have a new movie picked within 60 to 90 seconds,6 otherwise they could lose interest and move to something else. Therefore, the first steps of the new behavior should be easy and quickly rewarding.

6. https://www.businessinsider.com/how-long-netflix-thinks-it-takes-to-choose-content-2016-2

So, how could these insights on social change be used in companies to drive change within the teams?

Tool 8: To-Grip

In recent years, I have seen many leaders wrestle with the implementation of major improvement programs. They looked for ways other than carrying out analysis, planning, and managing costs. For this there is a practical tool for the agile leader: TO-GRIP. This tool supports brainstorming and continuous improvement. TO-GRIP thus supports the agile leader in creating an environment in which different teams implement major improvements together.

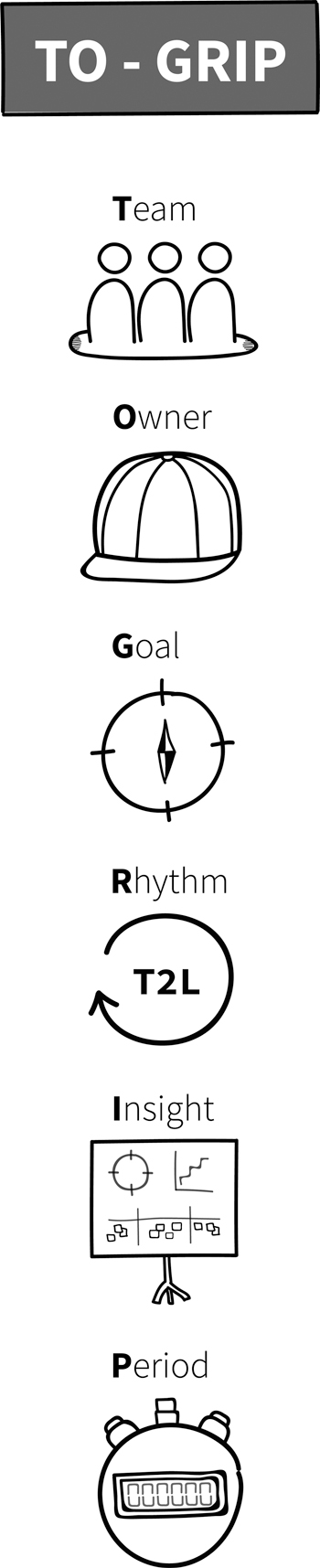

TO-GRIP, the eighth tool in this book, consists of six parts that can be defined and made into a concise story (see Figure 4.3). Every part is important for the tool to work properly. At the start, not all the parts have to be in place; these parts could be filled in after a few days or weeks. The tool is based on the idea of social or viral change, in which change or improvements are initiated by a few and copied by others. It can be used for improvements, strategic points, or major changes. Both agile leaders as team members or informal leaders can take the initiative to use this tool.

Figure 4.3 Tool 8: TO-GRIP

In a workshop with various employees, TO-GRIP is created and filled in around one theme. Thanks to the six components, the theme becomes very measurable, expectations become explicit, and concrete agreements on the cooperation are made for the coming period.

Let’s have a closer look at the parts of this tool.

|

|

Team Who will drive the change? Which small team of people will probably have great power in creating the change? This could be an existing team or a newly formed group of people from different teams. This team formally gets the right amount of freedom to take ownership (see Part 2, “Facilitate Ownership”). For example, this mandate could be on setting standards, changing existing rules that block the change, or buying the necessary products. |

|

|

Owner Who is the leader behind this change? Who takes responsibility for the consequences or mistakes made during the change? This person is either a manager with a mandate or another person who can quickly get approval on changes needed. This will be the person that drives the change, empowers the team, and sets priorities where needed. He has a (shared) vision for the change on both the current pain and the desired passion (see “How Do You Handle Resistance to Change?” later in this section). |

|

|

Goal What is the challenge, problem, or improvement? What is the measurable goal that we want to achieve? How is this translated to a (positive) customer impact? A good practice is to have a tangible metric with a trendline to measure the progress. (See “How Do You Measure Change?” later in this section.) A good practice is to add a slogan and a visual icon or logo. |

|

|

Rhythm When will the team meet? What is the timebox? What is the expected T2L? In complex environments, the change can’t be planned or scheduled. Rhythm is the alternative for a detailed plan. Rhythm builds structure, and it enables us to:

We don’t know yet what we’ll be doing after one month, but we do know that every week we’ll use the latest insight and experience to improve, and we will keep everybody informed. |

|

|

Insight Insight is a tangible and transparent insight on status and progress. A good practice is to have this on a fixed place physically on the wall. This is where the team members have their rhythm but also where the stakeholders get informed on progress. If somebody else wants to know the status, he can walk to the board and ask for background information. It’s based on the concept of visual management.7 Tools like VLB, T2L, and KVI are probably used on this insight board. |

|

|

Period After how many weeks or months do you have a stop-or-continue moment? For which period do we ask for commitment from the team? This is the formal review to see whether we continue. In complex systems, success can’t be guaranteed. Sometimes it’s better to just stop this improvement and try something totally different. It’s a good practice to also celebrate the stop or failure because the organization still learned a lot through trying to improve this particular thing. |

7. https://www.isixsigma.com/dictionary/visual-controls/

The acronym of the six parts results in the name of this tool: TO-GRIP. In this way, both the agile leader and the agile teams have control over improvements, strategic points, or major changes.

Let’s have a look at a concrete example of this tool (Table 4.8). A big financial software company already worked with agile for a few years. They are in the midst of implementing a faster way to deploy software by adding automatic tests and automating the deployment of software. But the customers and users are complaining that new functionality takes too long and that when the new functionality is available it doesn’t meet the expectations nor does it really work well. Several people want to improve collaboration with real users. They want to use the feedback of the users more intensely. The users who also wanted to collaborate more were called “first users” because they got to see and use the functionality the first. Together with first users, the team members want to launch new functionality and then, when these first users are satisfied with the functionality, it’s gradually launched to more customers and users.

Table 4.8 Example of implementing co-creating with users

Team

|

A few people from different agile teams formed a taskforce to implement this improvement. Most of them got some experience already in working very closely with users. After brainstorming, they gave themselves the name “Co-enablers.” They expect that each member will need to spend roughly 4 hours a week to implement the improvements. |

Owner

|

The product manager is the leader behind the change. He really has passion for the topic and can set priorities where needed. He works closely with the development manager who is the hierarchical leader of most of the agile teams. |

Goal

|

During the first meetup of the Co-enablers and the product manager, they brainstormed on a tangible goal. The T2L was quickly picked. Looking at the current implementation of new functionality, they discovered that the T2L currently was between 9 and 15 months. They derived a trendline of the existing T2L. The slogan they created was “Not what I want, but what I need!” described from the perspective of the users. |

Rhythm

|

The team meets every two days. They work on feedback and impediments mentioned by the agile teams. They use the time together mostly to:

Every two weeks they have a review meeting8 lasting an hour. The vision is repeated, stakeholders are updated on the progress made, and larger impediments are shared to find common ground to fix them. |

Insight

|

At a central point, the Co-enablers have posted a large physical board. A good webcam is pointed at it so members of the change group can also meet remotely. They track the progress of several teams in categories of “Waiting,” “First steps,” “First success,” and “Promoter.” The 17 agile teams of the department are plotted in these categories to see where they are (see section “How Do You Handle Resistance to Change?” for more details). |

Period

|

The period is set to 9 months. The definition of success is that at least three major new functionalities are successfully done in co-creation with a T2L of less than 1 month, where “successfully done” means an 8 or higher on user satisfaction and more than 25% of the users are using the new functionality. |

At www.tval.nl there are several other concrete examples of the use of this tool.

With TO-GRIP, the agile leader can initiate improvements that stimulate an agile culture of collaboration, knowledge sharing, stopping things that don’t work, and learning by doing. TO-GRIP offers a concrete tool for more structured solutions. This creates a healthy habit of making major improvements, intervening from the agile leader who contributes to the agile culture. Only then are teams able to continue to grow, cooperate, and take more and more independent initiatives.

How Do You Measure Change?

Is it important to measure the change? Isn’t it enough to see the happiness of the people who work on it? Of course the happiness is very important, but always somewhere along the line the question pops up: how are we doing and what did we achieve? Due to micromanaging and measuring the wrong things, some people have an aversion to measuring progress or performance. But when the right things are made transparent and the right ambitions are set, over and over again this brings focus and synergy! It makes the progress transparent and makes explicit what interventions worked and didn’t work. Finally, it convinces stakeholders who are still in doubt or even against the change that improvements are made. But how can we measure the change properly?

How can the change be measured in such a way that progress is made transparent? One pitfall is to wait for the final impact of the change on customer satisfaction or even turnover. But often this takes too long to really emerge, and the correlation between the increased happiness and this improvement is at best not one-to-one and is often vague. Another pitfall is to measure only the activity, such as only the number of hours spent on improvements or the number of reports or functionality deployed differently. So how can the change be measured properly?

A practical way to measure is splitting it into three different categories: the output (what is done), the outcome (what is achieved), and the impact (what is the result). Measuring all three gives both focus on the end goal and makes explicit what we have done to reach it. Let’s have a look at the co-creation example to explain these three categories (Table 4.9).

Table 4.9 Implementing co-creating with users

Category |

Description and Example Metrics |

|---|---|

Output |

This category measures what has actually already changed and what change has been made. This only measures the activity but not yet the success of the change. For example:

|

Outcome |

The outcome category measures the first signs of improvements.

|

Impact |

The impact category measures what we really want to achieve with the improvement. A combination of impact for the customer and value for the company (see Part 1, “Co-Create Goals,” for more information).

|

How Do You Handle Resistance to Change?

Resistance to change is inevitable and comes in different categories. It’s inevitable because teams and individuals in ownership mode (see Part 2) will ask questions and raise their concerns on ideas, practices, or approaches from leaders or other teams. This is often the category of “Let’s think it through first,” which is a crucial ingredient for their craftsmanship and maturity. Without this natural tendency to resist change, they will go with every new idea and just follow today’s wind. The teams ought to resist badly explained change or shallow (not well-thought-out) change. Highly mature teams need a decent critical-thinking hat to start properly with new technologies or new features. Without it, they will overlook the consequences or the long-term effect. The highly mature don’t like change, but they love involved improvements. Therefore, most of the resistance is feedback to the agile leader on his behavior. But just as a farmer doesn’t blame his crops for not growing or thriving but uses it to adapt and improve his farming skills and create a better environment for his crops, successful agile leaders use the resistance to improve their skills and approaches.

![]() Mature teams hate change but love improvements.

Mature teams hate change but love improvements.

But when resistance is inevitable and has different shapes or categories, how can an agile leader successfully initiate change without being bogged down by resistance? A good way is to know the different categories and have a conversation with the teams about which category they think it is. The latter really drives the crucial culture attributes of transparency and candor. Using tool 8, TO-GRIP, already addresses a lot of the following categories, but still it’s good to know and recognize the different shapes of resistance. Let’s have a closer look.

The important resistance categories are

Why—Teams need to know the why behind the change. What is the objective, and what is the purpose of it? In co-creation with the informal leaders, this why has to be made explicit so that the change is not really a change but in fact an improvement. Again, agile leaders need their teams to resist any badly explained change. This motivates the leader to improve, to stop with bad ideas, and to better explain the improvement and the benefits of it.

Urgency—Tough improvements also need an urgency. If the improvement isn’t achieved, something has to (likely) go wrong or tangible opportunities will be missed, such as employees leaving, customers complaining, or new deals being missed. This is especially crucial for tough improvements: they need a lot of effort and investment before the benefits are achieved. This could be in terms of tangible things like fixing bugs or solving long-lasting issues and also intangible things like habits changed or collaboration improved. Often this resistance is not explicit. People and teams like the improvement but, after a few weeks, nothing has really changed. When asked, people like to improve and spent time on it, but again in hindsight no real investment was made. Therefore, this resistance is not on the individual level nor on the team level, but on the system level (see Peter Senge and his work on system thinking9). Often, both setting clear priorities and supporting the teams to really spend time on it are crucial to conquering this resistance on the system level.

How—Depending on the maturity of the team, the how should be clear. Teams at a low maturity level need more details than highly mature teams (see Part 2 for more details). This resistance on the how comes in different shapes. People can resist instructions or approaches. To the leader, it may seem that they resist the whole, but actually they only resist several parts. Others can resist change because the unknown frightens them. Giving more details on how the change will look and what the consequences are often removes this fear of the unknown. In communicating with different teams, successful leaders incorporate both in their stories. They find the balance in giving details and examples without prescribing it to the more mature teams. It’s often better when several informal leaders give examples regarding how the change will look.

Forced—This is one of the most difficult categories. These people and teams are resistant to the improvement because they feel they are forced into it. They might see the benefit, the urgency, and the how, but they just don’t want to change because it’s mandatory. It’s one of the most difficult categories because the resistance could be based on egos or because they don’t get enough freedom based on their maturity. For an agile leader to know which of the two it is is difficult because the perceived behavior of the people and the team are the same. Informal leaders showing resistance because of their egos is bad. The agile leader should often be very strict and sometimes even be harsh to these informal leaders. Their egos should never be more important than the benefit and well-being of the whole. But when the agile leader makes a wrong judgment and is harsh toward the well-intentioned informal leader, it’s likely that transparency, trust, and openness go down the drain. Also, when the agile leader isn’t harsh and doesn’t publicly criticize the attitude of the informal leader, the culture of group-interest, sharing, and helping is going down the same drain. Trying to really understand the informal leader and have a heart-to-heart conversation before making decisions is a practical tip.

Change fatigue—The last two categories are feedback that is particular to the agile leader’s attitude and communication. Teams and people that show this type of resistance are often still working to harvest the fruit of the previous improvements and don’t want to work on another improvement just yet. They know the why, the how, and also the urgency. But other improvements are still going on. Successful agile leaders don’t start a lot of individual improvements; rather, they tell the journey and the dot on the horizon and let teams and individuals decide on the speed and ordering of the improvements needed to reach the dot. They overcommunicate the overarching story and objectives and are experimentors of the learning journey.

Fear—Being afraid of the unknown is a natural emotion. When the department is scared about the upcoming change, it’s often because they doubt the effect it will have on them. The fear can be for their job security, of being unable to achieve the change, of having insufficient skills, of being unsuccessful in their new role, or of working together with people they don’t know or just don’t like. All kinds of fear could be present but are often because they don’t trust the leader to make the change successful, or they may doubt the motivations of the agile leader behind the change. A leader of a financial organization overcame the fear within his department by just being radically open about the things he didn’t know yet and the things he didn’t like about the necessary change. But he showed confidence that together they will make the change successful. And both his history and his latest results proved that he was very well able to lead an organization through fears of the unknown.

9. https://www.amazon.com/Fifth-Discipline-Practice-Learning-Organization-ebook/dp/B000SEIFKK

A practical way to solve resistance is, first of all, to accept that resistance to change is crucial because this will also result in a steady status afterward. When the people see the value in the new way of working, they will start to lower resistance and start being an enabler for change. They will voluntarily take ownership of the ambition and make the change successful. They will show the same resistance again when a change is proposed that wants to throw away the successful change.

It’s the role of the agile leader to use the power of the change team and to give them enough structure so they can enable the change in the rest of the organization. The practical tool TO-GRIP will support the agile leader in this structure by showing confidence and giving enough mandate and authority to this change team together with a tangible goal, powerful rhythm, transparent insight, and clear evaluation moment. These ingredients of the TO-GRIP tool will help the agile leader to create a successful and powerful culture for continuous learning and improvement.

Summary of Part 4—Design Healthy Habits

Agile leaders give their teams a lot of freedom, space, trust, and inspiration for their daily work to increase their customer impact. They shift to the background and do not feel the need to be needed nor to interfere with the daily work. If the goals are inspiring (Part 1), if the teams take ownership (Part 2), and if the T2L is short (Part 3), the agile leader can focus on the culture. He can repair and improve this and thus create an increasingly better environment for his self-managing agile teams to thrive.

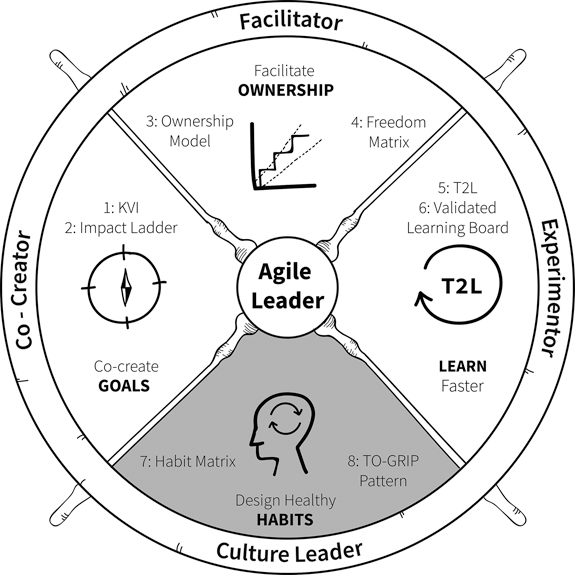

Culture follows structure (Larman’s law) and therefore continuously improving things like KVI, the Ownership Model, and the T2L is crucial for improving the culture. But improving the culture also requires designing better habits and influencing the informal leaders. See the previous figure for an overview of the tools in Part 4 that will support the agile leader in improving the culture. Besides continuously improving the structure, the underlying habits and informal influencers can be improved by following these four steps:

Discover a part of the culture you want to improve.

Together with a few people, brainstorm on the habits that drive the existing culture.

Discover new, healthy habits that drive the desired improvement.

Anchor the improvement by adjusting symbols (reports, overviews, lists) and guiding informal leaders (heroes) to show the right behavior.

This drives culture change by continuously changing small parts—not with a big-bang change but by creating a viral change. Successful agile leaders have a keen eye for both the habits and the influencers in the organization because they understand how these two can be used to continuously improve the environment.

Habits are an important way to influence and change the culture. Habits are actions of employees and teams, triggered by a situation, that are rewarded in the short term. This makes the behavior more and more routine. Habits can be used to improve the culture by finding an alternative for bad and unhealthy habits. Bad habits have a long-term effect that undermine the desired agile culture. The solution to these bad habits is not to forbid them or enforce a changed behavior but to reward new behavior in the short term. As a result, the negative long-term effect of bad habits is replaced by the positive long-term effect of new good habits. This creates a better culture. The Habit Matrix helps to recognize unhealthy habits and replace them with healthy habits. This seventh tool for agile leaders clarifies habits, triggers, or cues; the short-term incentive; and the long-term consequences. With the Habit Matrix, brainstorming can be done to discover new habits that do contribute to the agile culture.

As habits continue to improve, it is important that the agile leader focuses on symbols and heroes. The heroes are the informal influencers of the teams. The symbols are reports, overviews, and bonuses. By connecting symbols and heroes to the desired agile culture, the new culture is actually anchored.

Finally, it is important that improvements and strategic themes involving multiple teams are also part of the agile culture. TO-GRIP, a set of six components, helps the agile leader to implement improvements and strategic themes in a constructive manner. With this eighth tool from the toolkit, the agile leader stimulates the culture of teamwork between teams, improving the customer’s impact and quickly learning from feedback from users.

The Agile Leader as Culture Leader

If the going is tough, if pressure is on, it is all the more important that the agile leader guards the culture. Because if, under pressure, short-term incentives of good behavior are not met, it will destroy collaboration, long-term investment, and mutual learning. This is automatically the moment when unhealthy habits can quickly take root. The carefully constructed and costly agile culture can crumble. Agile leaders recognize these moments and then come to the stage. They stick out their necks, show guts, pull teams through the difficult period, and continue to restore and improve the culture. That makes them real leaders.

Concrete Questions

The following are some questions to put the tools, examples, and ideas from Part 4 into practice.

In which situations is it especially difficult for you to be a leader?

What habits do you create for yourself to stay healthy as a leader?

Who will inspire you and motivate you? And who will serve as motivation when you go through a tough time?

Notes

_________________________________________________________________

_________________________________________________________________

_________________________________________________________________

_________________________________________________________________

_________________________________________________________________

_________________________________________________________________

_________________________________________________________________

_________________________________________________________________

_________________________________________________________________

_________________________________________________________________

_________________________________________________________________

_________________________________________________________________

_________________________________________________________________

_________________________________________________________________

_________________________________________________________________

_________________________________________________________________

_________________________________________________________________

_________________________________________________________________

_________________________________________________________________

_________________________________________________________________

_________________________________________________________________

_________________________________________________________________

_________________________________________________________________

_________________________________________________________________

_________________________________________________________________

_________________________________________________________________

_________________________________________________________________

_________________________________________________________________

_________________________________________________________________

_________________________________________________________________

_________________________________________________________________

_________________________________________________________________

_________________________________________________________________

_________________________________________________________________

_________________________________________________________________

_________________________________________________________________

_________________________________________________________________

_________________________________________________________________

_________________________________________________________________

_________________________________________________________________