The conclusion of hostilities in Tunisia cleared the way for future Allied operations. Seizure of Sicily was to be next, as decided in the preceding January during the Allied conference near Casablanca. Components of the Allied force for the Sicilian operation had been selected, and final plans and preparations occupied the next month and a half. At Quebec another Allied conference produced a decision to invade southern Italy as soon as Sicily had been secured, with the goal of liberating Rome. Surrender by the Italian government to the Allies was expected to precede the second invasion. Forcing a withdrawal of German forces up the Italian peninsula to the Po Valley or the Alps was also thought to be not only possible but probable.

For the invasion of Sicily (Operation HUSKY), American ground forces were to be known as the U.S. Seventh Army under Lieutenant General George S. Patton, Jr., a command consisting of U.S. II Corps under Major General Omar Bradley and, as circumstances developed, a U.S. Provisional Corps under Major General Geoffrey Keyes. The British Eighth Army, under General Sir Bernard Montgomery, was expected to land at the southeast corner of Sicily and attack generally north along the coast, past Mt. Etna, to Messina. The Seventh Army was to cover his western flank and sweep up the western part of Sicily and gain the harbor of Palermo near its northwest corner, before pushing north of Mt. Etna to Messina.

Controlling both armies was Headquarters, 15 Army Group, under the command of General Sir Harold Alexander, the ground force commander of the Allied Force. At that stage of the war in the Mediterranean area, British confidence in the performance of American troops, whatever their potentialities, had not yet been fully established.

The decisions to attack Sicily and mainland Italy confronted SIGINT planners with overlapping problems. They had to provide adequate "Y" service for the Seventh Army in Sicily and the Fifth Army in Italy, as well as for the Twelfth Air Force and for the commander, U.S. Naval Forces in North African waters, supporting the two armies. They had also to develop the level of competence of American "Y" units. A brief review of the SIGINT situation at this point may be useful.

The technical aspects of U.S. tactical SIGINT production remained for more than a year under the impediment of a NATOUSA security policy which obligated intelligence personnel to withhold from intercept personnel even the technical cryptologic information and intelligence requirements underlying their tasks. Instead, the intercept operators received daily assignments to cover specified frequencies and callsigns while SIS personnel supervised in order to ensure proper coverage. The production of "Y" by American SIGINT personnel had begun in Northwest Africa with field training; it required from three to five months for a unit to be able to perform well. That period was one of tutelage, while the more experienced British "Y" organization did what could be done to expedite the process. At the same time, all production of "Y" required endless adjustments and innovations by the British themselves to cope with the enemy's ingenuity in providing security for his radio communications and to surmount technical difficulties in collection. For the British, especially in the first months of campaigning with the Americans, it was tempting to continue improving their own SIGINT organization and to use Americans in a contributory role rather than to devote the necessary British resources to train Americans until they might act in a coordinate role. However strong the temptation, it could not wholly prevail against the determination of the U.S. Army to acquire the competence appropriate for its longer-run interests.

While American SIGINT personnel learned how to produce "Y" effectively in field conditions, American field commanders and staff officers had to discover for themselves the solid merit of SIGINT. Like their British counterparts, the American field commanders were skeptical of its validity and careless about using what they got. In Tunisia they had to be shown. In Sicily American ground troops got along without much "Y" until the last few days. In Italy the U.S. Fifth Army and Twelfth Air Force began to make full use of "Y." On the Anzio Beachhead, "Y," like Ultra, played a major role.

For the British "Y" organization, once they had accepted the determination of their American allies to develop a tactical SIGINT service, the immediate goal was to insure that the overall Allied "Y" service operated efficiently; a second goal, to expedite training of the Americans. Partially trained Americans either had a few more experienced British personnel with them on temporary duty, or they "double-banked" with a whole British unit. Intercept operations were conducted at forward sites to provide more effective coverage as soon as that became practicable.

At AFHQ, as we have seen, the "Y" North Africa Committee became the instrument for coordinating activities and agreeing on policy. Meeting in March 1943 and semimonthly thereafter, it dealt with preparations for Sicily and Italy. The original chairman was Colonel Harold G. Hayes. The four British members varied, but each represented his armed service in the Signals Intelligence Section of G-2, AFHQ.[56]

In French North Africa a French SIGINT organization had operated clandestinely before Operation TORCH, in spite of the presence of German and Italian armistice commissioners. The location of the French unit had been known to the British. After the French in North Africa joined the Allies as belligerents, their SIGINT unit cooperated. By April 1943 about twenty-five intercept operators and analysts were engaged in collecting and analyzing traffic from German Air Force and Italian networks. Both raw traffic and analytic results came to AFHQ.

After French forces reoccupied Corsica, a detachment of the French "Y" service operated for a time at Calvi. Collaboration between British and French SIGINT producers focused on the German Air Force. The British gave to the French SIGINT chief (Commandant Black) a full set of the German Air Force codes known at GCCS as the "Orchestra" series. He was also told that the Allies in the Mediterranean area were benefiting from a SIGINT service based upon a greatly extended intercept cover directly from the UK, but that participation in it could not be broadened to include the French. The disclosures may well have allayed French suspicions that they were being denied knowledge of matters about which they should be informed.[57]

The first two United States "Y" units in the Mediterranean area, like the other combat troops in Operation TORCH, came from two geographically separate sources. The 122d Signal Radio Intelligence (SRI) Company with the Western Task Force crossed the Atlantic directly to the western coast of Morocco. The 128th SRI Company was sent from the UK to Oran, Morocco, as part of the Center Task Force. At Casablanca and Oran, detachments of each company were in the first or second convoy to arrive; the remainder of each company followed before the end of November 1942 With each detachment and each company as a whole were intelligence personnel detached from another American SIGINT unit, or, in the case of the 128th SRI Company, the British 55 Wireless Intelligence Section (WIS), consisting of three officers and twenty-two of other ranks. All were assigned to the Allied force. They were under the staff supervision of its chief SIGINT officer, the head of a SIGINT section in the Signals Division, AFHQ.

After the landings had succeeded and the French in Northwest Africa had joined the Allies in fighting the Axis forces there, the immediate objective of the Allied "Y" Service was to assist in the swift seizure of Tunisia. The 849th Signal Intelligence Service (SIS) was activated to provide American Army elements of the Allied Force with a field SIGINT center and with teams of intelligence personnel working with intercept operators of SRI companies. The teams would be attached to ground commanders (Army and Corps) and air commanders (Numbered Air Force or Air Support Command).

Compared to the United States, Iceland, or Northern Ireland, England was a better place for intercepting live German Army and Air Force radio traffic and for learning the intricacies of effective coverage. The work could be done in tents, huts, or vehicles adapted for the purpose, but actual, rather than simulated, ground combat conditions in the West were to be experienced in 1943 in the Mediterranean area only. Before it could be known how extensive and prolonged the campaigns there would be, ETOUSA sent more personnel to Algeria to become the basis of an American "Y" Service, while others went there directly from the United States. When NATOUSA was activated on 3 February 1943, the 849th SIS became the theater equivalent there of SIS, ETOUSA, in the UK. The latter could not avoid thinking of the diversion of its SIGINT personnel to the Mediterranean area as a drain instead of a seasoning process, but the experience gained was to be turned to account in preparing for the campaigns in western Europe.

The 849th SIS was activated at Fort Devens, Massachusetts, on 2 December 1942 with a strength of sixteen officers and 102 enlisted men. On 14 January 1943 the new unit, under Captain Richard L, Downing, embarked for Algiers, where it arrived on 1 February 1943. Meanwhile, another group of intelligence analysts, trained at Vint Hill Farms Station and Arlington Hall Station of the Signal Security Agency, was formed on 8 November 1942 as Signal Intelligence Detachment 9251-A and shipped to the United Kingdom for advanced training in SIS, ETOUSA. After that training was completed, it moved to Algiers, arriving there on 20 February 1943. Its strength was then fourteen officers and seventy-seven enlisted men. It provided much of the original personnel of the Intelligence Branch, 849th SIS.

Men like Major Herrick F. Bearce, who had come to Morocco with the Western Task Force, Major Millard F. Rada, who had been in London with Signal Intelligence Division (SID), ETOUSA, and Captain Richard J. Doney, who had been there in the original SIGINT Section, AFHQ, were already in Africa when NATOUSA was established and before the 849th SIS arrived. They and a few other officers were assigned to the 849th SIS.

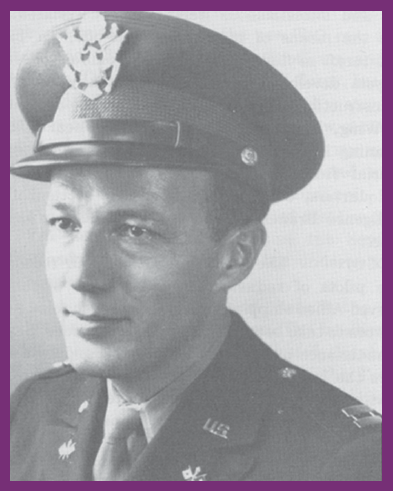

Captain Richard L. Downing, 1942 (Photograph courtesy of the Department of Army)

In the United States, when the 849th SIS was being planned, it had been expected that it would become an AFHQ staff element. The table of organization and the special list of equipment for which War Department approval was obtained were based on the belief that direct support would be received from Allied headquarters units. Instead, it was sent to operate in the field at Hammam Melouane, about thirty miles from Algiers, without the necessary "housekeeping" personnel and equipment. Major Rada became its commanding officer.

Like SIS, ETOUSA, the 849th was responsible for communications security, as well as communications intelligence, among United States Army organizations. Part of its mission was thus distribution and accounting for cryptologic systems, equipment, and material, and the security monitoring of their use.

The site taken by the 849th SIS at Hamman Melouane included buildings previously used by the French. At first, the electric power supply that had met French requirements with a thirty-kilowatt transformer gave much trouble. Fuses blew and had to be repaired rather than replaced. Circuit breakers separated. Insulation burned. Until the supply could be increased, it was necessary to establish a rotating schedule for the use of power for light in offices, mess halls, kitchens, day-rooms and quarters, and for operating the photographic laboratory and the communications equipment. An auxiliary five-kilowatt generator was found and a certain amount of rewiring lessened the inconveniences. Not until June 1944 did the 849th obtain two new diesel-powered, thirty-kilowatt generators. After a move to Italy, two more generators were added.

Communications technicians in the 849th SIS installed telephone and radio connections, and organized a message center which linked the Intelligence Branch at Headquarters with its detachments by radio and teleprinter. A captured German fifty-watt transmitter was first used with a U.S. Army receiver. In August 1943 an SCR-188, then one of the Army's better receivers, was installed, enabling the communicators to use a wider range of frequencies and more power, and, when replacement parts were needed, to obtain them more rapidly. Later a 500-watt transmitter came into service.

Headquarters, 849th SIS, had executive, administrative, and "overhead" personnel. The two main operating elements were the Intelligence and [Communications] Security Branches. A third element was the Enemy Equipment Intelligence Service, which included a Laboratory and Analysis Section, Editing and Publications Section, and two field detachments. The Intelligence Branch was supervised by the SIGINT Section, Signal Office, AFHQ (Lieutenant Colonel Harold G. Hayes), through Headquarters, 849th SIS, which furnished its products to G-2, AFHQ, through the same channel. The Telephone Monitoring Section of the Security Branch was also in direct touch with the Signal Office, AFHQ.

In February 1943 the new Intelligence Branch, 849th SIS, consisted of sections concerned with traffic analysis and cryptanalysis ("solution"), all working on low-grade German Army and Air Force traffic collected by the SRI companies as they arrived and set up their apparatus. A unit known for a while as the "Fusion Section" coordinated intercept and exploitation tasks, controlling intercept with information gained from a variety of intelligence sources. By May 1943 the changed nature of its work was reflected in a new designation, Records and Research Section. For almost a year more, it maintained records on German Air Force order of battle, compiled in the main from special intelligence and supplied via SID, ETOUSA, in London.

The Intelligence Branch, 849th SIS, created eight detachments. They were allocated, in association with parts of the four SRI companies that came to the Mediterranean, to Army and Army Air Forces commands. The 128th SRI Company, after participating in Operation TORCH, moved to Tunisia from the Oran area in January 1943. The 122d SRI Company, also in Operation TORCH, left the Atlantic Moroccan coast in January 1943 for training near Algiers. The 123d SRI Company arrived in Algeria directly from the United States in March 1943. Like the 122d, it served the Twelfth Air Force. The fourth SRI Company to arrive in Africa was the 117th, which came by sea directly from the United States to Oran, and thence to Boufarik, Algeria, on 30 March 1943.

Three detachments of the 849th SIS and two SRI companies were trained in North Africa to produce air tactical SIGINT. Detachment "D," formed in February 1943, and Detachment "F," formed in July 1943, worked with parties from the 122d and 123d SRI Companies on German Air Force low-security radio and VHF radiotelephone communications. Detachment "G," the third, was organized in July 1943 to process encrypted weather reports intercepted by a segment of the 122d SRI Company, and to pass them to intelligence units of the American tactical (Twelfth) and strategic (Fifteenth) Air Forces from a station near Foggia, Italy. Detachments "D" and "E" (VI Corps) both participated in the campaigns at Anzio and in southern France. Detachment "F" was involved, with the 123d SRI Company, in the formation of the 9th Radio Squadron, Mobile, USAAF.[58]

Comparable to German low-level ground force communications intelligence was that from German Air Force units. Aircraft-to-aircraft in flight, ground nets supplying navigational aids to aircraft in flight, messages passed point-to-point dealing with aircraft movements, reports by pilots of ship sightings, traffic on the enemy's safety service (rescue) nets, and miscellaneous items, when correlated, became the means of recognizing take-offs, air bases, and aircraft in flight on long-range bombing missions. Analysts developed competence gradually, aided by the instructions furnished by experienced analysts of 329 Wing, Royal Air Force, stationed near Algiers. Beginning in March 1943 they got their intercepted material from the 123d Signal RI Company. At Headquarters, 849th SIS, all but one section of the Intelligence Branch worked on low-grade German air traffic.

The practice of German air-reconnaissance pilots of radioing detailed reports when they observed Allied shipping or land convoys enabled Allied monitors to take bearings on the transmissions. Several reconnaissance planes were intercepted and shot down before the practice of reporting directly from aircraft was stopped. Later, at Anzio, the interception of such reports made it possible to warn ships, ground installations, and even artillery spotter planes to expect German air attacks. Occasionally, German ground controllers were heard vectoring fighters for attacks on Allied aircraft in flight, thus allowing a flash warning to be passed to the intended victims.

German communications were mostly plain language intermixed with jargon codes. An experienced monitor could tell whether the transmission was coming from a ground station (characterized by a lack of motor noise), a fighter aircraft (which employed standardized procedures and frequencies and was characterized by a larger number of voices during combat and by stereotyped orders concerning altitude and course), a reconnaissance aircraft (which made references to weather), or a training flight (which contained instructor's maneuver commands).

During flight, either aircraft were heard reporting their own positions, or they made it possible to locate them by taking DF bearings on their transmissions. Allied intercept operators were often able to report the number, type, position, altitude, course, and mission of an enemy formation and the fact that it had reported seeing Allied aircraft. Voice traffic among the German pilots could be heard well before Allied radar scopes disclosed their position. The extent to which SIGINT successes were masked from the beneficiaries by attribution to radar or other sources of intelligence was to leave largely unappreciated the actual role of SIGINT teams.

In June 1944 two detachments with Army commands were reorganized and redesignated. Detachment "A," with Headquarters, Fifth Army, became the 3200th SIS Detachment (Type A), working with intercept operators from the 128th SRI Company. Its authorized strength under the new T/O rose from three officers and eighteen enlisted men to five officers and thirty-eight enlisted men. Detachment "E," with VI Corps, became the 3201st SIS Detachment (Type B), with a strength of three officers and eighteen enlisted men. In its new status it accompanied VI Corps into the Seventh Army under General Alexander Patch as that command made ready for Operation DRAGOON. A third unit, Detachment "B" (five officers and twenty-six enlisted men) and the 117th SRI Company in 1944 became the Seventh Army's Headquarters "Y" section but underwent no unit redesignation.

In May 1943 a new phase in the field training of American "Y" units began. The intelligence personnel at headquarters were distributed elsewhere. The original Solution Section and part of the Traffic Analysis Section were assigned to a new Detachment "F," 849th SIS. The men moved from Hammam Melouane to Boufarik, Algeria, in order to train with RAF "Y" service experts. The other part of the Traffic Analysis Section moved to Constantine in eastern Algeria to work with a party from the 122d SRI Company, which was engaged for a short period in attempting to intercept high-grade traffic for transmission to Arlington Hall in Washington for processing. They also collected German and Italian encrypted weather reports.

At the end of the month, as plans for developing SIGINT capabilities that were commensurate with American Army and Army Air Force undertakings in the Mediterranean seemed to promise success, they received a severe jolt. As far back as 10 February 1943, the War Department had been asked to authorize and man a pool of SIGINT personnel in the Mediterranean, a group able to process German and Italian military communications by radiotelegraph and radiotelephone. It was planned that analysts would reach the Mediterranean after a period of suitable training in the UK The 849th SIS would manage their use. When they arrived, however, the specified requirements had been disregarded. The Signal Security Agency had had no opportunity to screen the officers and men selected. Proficiency in German or Italian languages had not been assured.

The Signal Security Agency had not been able earlier in 1943 to meet a requisition from the chief SIGINT officer, AFHQ. He had been given officers trained in Japanese, French, and Spanish, and meteorological SIGINT, whom he was ready to have returned to the United States for assignments where they could be better used, and to keep only two officers who knew German.

Detachment "H" was the last to be created. Most of its members had come to Northwest Africa in September 1943 after passing a short course in the analysis of low-grade German Army systems. They then began a few months of training in Sicily before moving to Italy (near Caserta) in December, with a detachment of the 128th SRI Company and, temporarily, Detachment "A," 849th SIS. From January 1944 to the end of the war, Detachment "H" was the SIGINT unit with Headquarters, II Corps, being redesignated in February 1945 as the 3915th Signal Service Company (RI).

These items pertaining to the union of detachments of the 849th SIS and detachments of the SRI companies demonstrate that in the Mediterranean area production of tactical SIGINT was accomplished by improvising suitable units. To look ahead, the operations in which those teams of intercept and intelligence specialists were to participate demanded flexibility in organization. The campaigns included five major amphibious assaults. They extended from southern Tunisia to northern Italy and southern France. Air operations from the bases in Italy ranged far into southeastern Europe. The SIGINT team went through intermediate and advanced training under combat conditions and then into full production. The administrative processes of the U.S. Army called for standardized organization determined by adequate operational tests. In 1944 and 1945, certain new designations for modified tables of organization were applied in the theater.

An important consequence of the establishment in 1944 of Corps Signal Service Companies (RI) was the termination of the dual chain of command over SIGINT teams when two types of detachment interceptors and analysts were united. Under NATOUSA policy, SRI intercept operators had been denied access to technical SIGINT information, including the information governing selection of their intercept assignments. They received daily assignments to cover specified callsigns and frequencies; the SIS personnel had supervised intercept activities to insure correct coverage. After the merger, the barrier between the two types was abandoned. That was a major change for the 3915th Signal Service Company with II Corps, and in the 3916th with the IV Corps (under General Willis D. Crittenberger) in northern Italy. IV Corps had been served by the British 100 Special Wireless Section and a detachment from the 128th SRI Company until the new 3916th was formed; the British stayed on until April 1945, while the American analysts became expert. Since the central effort to change organization was that of ETOUSA, the subject will be taken up in more detail in that portion of this history.

During the westward movement of British Eighth Army across Libya into Tunisia after the Battle of El Alamein, the lengthening distance from the advancing SIGINT units with the Army Headquarters, the three Army Corps, and the Western Desert Air Force, to the base SIGINT center back in Egypt affected production adversely. On 20 February 1943 the shift of Eighth Army's subordination from GHQ, Middle East, to the new Headquarters, 18 Army Group, Allied Force, required adjustments in the SIGINT structure. When Eighth Army was selected to make the main effort in Sicily with a five-division assault, that also prompted adjustments. Once it was decided in July 1943 that, after Sicily, the Allied force would invade southern Italy, the prospect for Allied operations in the Balkans or eastern Mediterranean areas diminished greatly. Some British SIGINT resources in the Middle East had already been used in Tunisia and Sicily; in order to be well employed, others had to be brought west.

To cope with SIGINT production from Italian traffic, British Army and RAF sections that had worked in the Western Desert on Italian Army communications were flown into Tunisia. There they supplemented what a cooperating French "Y" organization was able to provide.

With General Alexander at Headquarters, 18 Army Group, at Ain Beida were British 40 WIS and 107 Special Wireless Section, operating in vans.

The 122d SRI Company moved to Constantine on 28 March 1943, relinquishing its quarters at Boufarik to the 117th SRI Company, which shifted eastward from Oran. In May the 122d moved via Bone, to La Marsa, near Tunis; the 117th shifted from Boufarik to Bedja; and the 123d SRI Company, with Detachment "F," 849th SIS, then moved to Boufarik.

Within a week after the Axis surrender in Tunisia, a small British intercept unit began operating at Fort du Kebir, three miles from Bizerte. Soon elements of two U.S. intercept companies occupied adjacent sites. At Bone the Royal Navy and at La Marsa the RAF developed stations for producing field SIGINT. SIGINT communications from Bizerte to Algiers, for relay to London and Washington, enabled the Americans to pass intercepted enemy traffic in high-grade and medium-grade systems for processing at national centers.

It was not long before U.S. participation in producing special intelligence from German communications was covered by an Anglo-American agreement, causing American intercept resources in Tunisia or Algeria to be turned to other targets.

For a while after the Axis surrender in Tunisia, a dearth of enemy high-level radio communications seemed to confirm an apprehension that on the continent such traffic would be carried by wire. Production of special intelligence like that accomplished while the German Army and Air Force commanders in Africa kept in radio touch with their superiors in Europe seemed likely to have come to an end. Happily for the Allies those forebodings were shown to be false during preparations for, and the actual defense of, Sicily. Both the German Air Force and the German Army on the mainland resumed the kind of radio traffic from which special intelligence of great value to the Allies could be extracted.

Special intelligence on the buildup of Axis forces in Sicily was carefully sought and studied. The transfer to Sicily of German troops from the mainland was observed in some detail. The divisions, tanks, guns, and vehicles became known, and their disposition was inferred. The calculation set the total at about 45,000 German ground troops and over 100 German tanks, most numerous in eastern Sicily. Attempts by the Allies to mislead the enemy so that he prepared for an attack elsewhere were only partly successful. In the event, the main cause of tactical surprise at the time of the landings was to be like that experienced later in Normandy: the onset of stormy weather while the convoys were en route.

The concentration of Allied vessels in the ports from Oran to Tripoli did not go unnoticed or unopposed by the enemy. One of the objectives of Allied "Y" service was to anticipate German air attacks on the coastal convoys and the ships moored in ports behind barriers of mines, under concealing smoke, and within a screen of antiaircraft artillery. When a German aircraft shadowed an Allied coastal convoy (if so ordered by its controller), it emitted homing signals which guided attacking planes to the target for action after dark. Interception of enemy reports and homing signals might, however, lead to a disrupting Allied air operation before the vessels could be struck. Enemy submarines also preyed on convoys between Algiers and Bizerte and had to be watched. The Lac de Bizerte was a high-priority target for German bombers, especially during the first week of July 1943 – a target protected by antiaircraft guns and Allied fighters, with the assistance of radar and SIGINT to furnish specific warnings.

In June a German reconnaissance plane reported seeing a certain number of vessels at Bizerte. Both British and American intercept operators copied the report, but the British and American decrypts differed. The former translated the message as reporting forty-six ships, twelve under steam, while the latter construed it to be fifty-eight under steam.

The Mediterranean Air Command and the Northwest African Air Forces in May 1943 set up a command post at La Marsa to control all air operations against Sicily and mainland Italy relevant to Operation HUSKY. The Chief Intelligence Officer, (Group Captain R. H. Humphreys), Mediterranean Air Command (MAC), organized his division into sections making use of special intelligence or "Y," and sited them adjacent to a Special Liaison Unit. The SLU worked twenty-four hours per day and gave direct service from the Air Ministry, Bletchley Park, and Headquarters, Mediterranean Air Command, in Algiers. One American officer worked with four British officers in the section handling SI on the German Air Force.[59] In a separate area for combat intelligence, three American officers dealt with "Y" and collateral non-SIGINT material. In a nearby trailer, one American and one RAF officer handled target intelligence.

The Combat Intelligence Section was in close touch with Headquarters, Northwest African Air Forces (NWAAF), at Constantine, which relayed data from its elements to La Marsa. At La Marsa Airfield, the photographic interpretation unit provided information gained from reconnaissance missions which were recommended, in the light of intelligence and operational requirements, as necessary. "Y" information came to the section directly from the "Y" unit at La Marsa.

The Target Intelligence Section of the Command Post was in touch with its counterpart at Headquarters, Northwest African Air Forces (NWAAF), and with the Photographic Recon-naissance Unit at LaMarsa. Its dossiers were assembled to meet the requirements of either strategic or tactical bombing missions, as indicated by general policy, by SI, or by other sources. When SI indicated that intended targets had already been sufficiently bombed, changes were made the next day. The guidance provided through these arrangements, and the execution of the missions which they supported, damaged severely the German Air Force in Sicily and Italy.

"Force 141," the planners for Operation HUSKY, provided for "Y" service to ground and air commands from command ships during the landings and from units ashore during subsequent inland penetration.

To provide field SIGINT to American ground troops of the U.S. Seventh Army in Sicily, the American SIGINT units that had been training in Tunisia set up three detachments of intercept operators, each with a section of analysts. As Signal Intelligence Officer, Major Herrick F. Bearce, who had been in Tunisia attached to the "Y" unit supporting II Corps, was attached for Operation HUSKY to the Signal Section, Seventh Army. The three groups of analysts were to be Detachment "A," 849th SIS (with Headquarters, Seventh Army), 52 Wireless Intelligence Section and Detachment "B," 849th SIS (with II Corps), and Detachment "E," 849th SIS (with 3rd Infantry Division, Reinforced). About 10 officers and 310 enlisted intercept operators and analysts were involved in those preparations.

Small advance parties, equipped with transmitter-receivers, a special cipher system, and one 3/4-ton truck for each party, were prepared for landings with the three segments of the American assault force. The remainder would continue working in the Bizerte area until the beachhead extended about ten miles inland and would then move to Sicily. There they were to take up their tasks at sites to which the advance parties would guide them.

Those plans were never executed, although by 20 June all were ready. A little later the advance parties embarked. The main body never heard from them again until near the end of the invasion. Not until 9 August did the main body arrive in Palermo; the next day two detachments joined Headquarters, Seventh Army, near San Stefano; the third went to Headquarters, II Corps.

First Lieutenant Herrick F. Bearce, 1941 (Photograph courtesy of the Department of Army)

"Y" service for Allied air controllers during the landings was to be supplied by one unit with each invading army. They would have to await the establishment of Sector Operations Rooms before their information could be applied, so they were assigned to the D+ 5 follow-up convoy from Tunis. Two RAF SIGINT units were designated to join RAF 211 Group and the XII Air Support Command, respectively. The RAF 380 Wireless Unit was ordered to form and equip one self-contained, mobile radiotelephone team large enough to cover two HF and four VHF channels and to operate two DF vehicles (HF and VHF). They were to work at Headquarters, XII Air Support Command. Enemy use of radiotelephone communications in Sicily, however, yielded little material for Allied "Y" production compared to later developments in Italy.

For British ground forces, General Harold Alexander's Headquarters, 15 Army Group, acquired a British "Y" unit at Bizerte before the invasion, and General Montgomery's Eighth Army Headquarters had a similar one. The two Corps used in the assault, 13th and 30th, each also had field "Y" units of standard organization. The intermediate field SIGINT processing center, known as the 7th Intelligence School, which provided analytic support during the invasion of Sicily, discovered that interception from Tunisia was unsatisfactory. It met that situation by working on traffic collected by forward elements and sent back by airbag until an analytic unit could be shifted from Tunisia to Sicily.[60]

When the British Eighth Army came into Tunisia and some of its innovations became known at AFHQ, they were thought to be worth adopting. One example was a "J" Service, a monitoring of the communications of Eighth Army nets for two purposes. The "J" units could report accurate information swiftly to the intelligence and operations staff divisions at Army and Corps levels. They could also detect breaches of communication security and report them through Corps to the offending divisions for correction and discipline.

The Combined Signal Board, North Africa, on 26 March 1943, favored such an activity for the Fifth Army, then training in eastern Morocco. Brigadier General Lowell Rooks, G-3, AFHQ, directed the chief signal officer to form an "American Staff Information Intercept Organization" from Fifth Army personnel, which would commence training by 19 April 1943.6 AFHQ also ordered two British officers on 29 May 1943 to provide "J" Service to U.S. Seventh Army during Operation HUSKY. They were attached to Head-quarters, I Armored Corps, Reinforced, and placed under control of the Corps G-2. The RI platoons of divisional signal companies did the monitoring, under control of Division G-2. They caught many examples of insecurity.[62]

The mobile forward "Phantom Teams" of observers provided information of great value, despite occasional inaccuracies, on the locations, situations, and intentions of the individual units in combat. Corps headquarters rarely reported the exact locations of individual units, so the "Phantom" reports to higher headquarters filled a gap in information. Moreover, their reports arrived in a more timely way. Because the reports described a unit's situation without the benefit of a bigger picture, they tended to be less "balanced" than they might otherwise have been. Their reports of Allied intentions were obtained usually at a level too low to be reliable. But whatever the shortcomings, Allied commanders found invaluable the information about units of the different corps on their flanks, information which thus became available to them via Army headquarters. Allied commanders seemed to be reticent about passing information directly to flank and higher echelons.

Defense of Sicily came under command of General Alfredo Guzzoni on 30 May 1943, a few weeks before the attack. As commanding general, Italian Sixth Army, he controlled four Italian and two German mobile divisions, the second of which, the Herman Goering Panzer Division, crossed to Sicily in June. General Guzzoni had also under his command six coastal defense divisions and lesser formations of Italian reservists. A German general with a small staff and a communications unit was liaison officer from O.B. Sued. The Sicilian populace was weary of the war and expected the Allies to win it. The island was short of food and transportation.

General Guzzoni's headquarters were at Enna, a central hill town southwest of Mt. Etna. The Italian XII Corps was responsible for the western, and the XVI Corps for the eastern, part of the island. At German insistence he split the armored elements into two major parts which were close enough to oppose Allied attacks wherever they began.

Although coastal defenses were spread rather thinly, three maritime areas were much more strongly prepared than others to deny access to ports. Under the command of the Italian Navy, clusters of coast artillery, antiaircraft guns, mobile batteries, motor torpedo boats, mine fields and special troops protected areas adjacent to Trapani on the west coast, Syracuse-Augusta on the southeast coast and Messina-Reggio on the Straits of Messina at the northeast corner. Having thus obliged the Allies to land over beaches, the defenders intended to delay by coastal defense forces and air bombardment the establishment of deep Allied beachheads. During the delay, mobile and armored columns would move to deliver overpowering counterattacks and to force withdrawal. If the Allies instead retained their beachheads, seized and captured a good port, they could be expected to grow stronger and become too powerful to be dislodged. The Axis forces would then face the choice of defeat by capture or defeat by withdrawal.[63]

The Allied Force established an advance command post on Malta, where General Eisenhower and his principal ground and sea commanders and their staffs kept their fingers on the push buttons. The headquarters of Air Vice Marshal Arthur Tedder, his air commander, remained in Tunis.

Two enormous naval task forces of warships, transports, landing craft, minesweepers, and other vessels conveyed the assault forces from African ports through seas that became stormy and rough but then abated during the transit. The Eastern Naval Task Force, under Vice Admiral Sir Bertram Ramsay, RN, carried the British Eighth Army of five divisions; about 250,000 men were aboard nearly 800 ships with 715 landing craft. The Western Naval Task Force, commanded by Vice Admiral Henry Kent Hewitt, USN, carried General Patton's Seventh Army; about 228,000 men were aboard 550 ships and 1,100 landing craft. Both armies included airborne troops to be dropped inland at key points to impede counterattacks and protect bridges from demolition.

Under General Alexander's Headquarters, 15 Army Group, the Allies entrusted the main effort to General Montgomery's experienced Army. Its initial goal was to capture an air base near Cape Pachino and the ports of Syracuse and Augusta, which were well prepared to oppose attacks by sea and air but less strongly organized against ground attack.

The key to Syracuse was a bridge (Ponte Grande) on the main coastal highway which extended over a canal and the wide, deep Anapo River, just south of the city near the head of the harbor. About 200 British airborne troops were dropped on a peninsula southeast of Syracuse. Eight officers and sixty-five enlisted men got to the bridge, removed the demolition charges, set up defenses against Italian counterattack, and held out for hours against infantry, artillery and tanks until relieved by advance elements of the British 5 Infantry Division. Only nineteen men survived. Their sacrifice enabled the Eighth Army to enter Syracuse before midnight of 10 July and to turn back German counterattacks later. By 14 July British troops and ordnance were being unloaded from transports in Syracuse harbor. The Eighth Army pushed north to the Catania plain, but there it was held to a slow advance at great cost.

The U.S. Seventh Army (Patton) had divided its assault forces into three elements which were headed for more than forty miles of coast – near Licata, on the west, Gela, in the center, and Scoglitti, on the east. Twenty miles farther east, the British beach landings took place. General Patton's first mission was to protect the western flank of the Eighth Army in a beachhead that extended far enough inland to encompass enemy airstrips and all positions from which the ships and beaches could be shelled. Reinforcements and resupply would have to come ashore over the beaches; no ports of consequence would be available. Like the Eighth Army's assault landings, those of the Seventh Army would benefit from naval gunfire. In fact, they were to find it invaluable.

Allied planes had previously bombed all but two or three of Sicily's airfields and seaplane, bases out of service, and had forced aircraft to take refuge from them at airfields on Sardinia and near Foggia. Those airfields also had been hard hit. The enemy was understood to have in Italy 600 bombers and 850 fighters. Northwest African Air Forces had about 3,680 aircraft. At first, the Allied fighters were used mostly to escort bombers that were striking enemy targets rather than to maintain combat air patrols over the armadas or to intervene quickly as enemy bombers approached. Requests by the commander of the Western Naval Task Force for air support had to be relayed through Admiral Cunningham on Malta to Headquarters, Mediterranean Air Command, in Tunis, whence orders went to aircraft that might be available.

HMS Largs was the command ship for the Eighth Army and its supporting air. The air "Y" unit aboard the ship had arranged with No. 10 Field Unit (RAF) on Malta to perform an essential service. At Malta all radio information and radar plots pertaining to the invasion were to be filtered from the normal welter of traffic and broadcast to Largs at half-hour intervals. The transmissions were given the codename CLATTER; they were helpful. The eleven positions on Largs could not, like the many receivers at Malta, monitor the numerous frequencies on which important information was passed; the Malta arrangement was turned to the advantage of all three services as material came in.

The Largs unit had borrowed from 10 Field Unit a noncommissioned officer who was adept in German Air Force traffic in order to avoid having to rely on a specialist in the very different German E-Boat traffic who had been officially assigned. From 13 to 15 July, the "Y" unit on Largs passed data to the RAF Senior Controller on HMS Bulolo and relayed some information to the XII Air Support Command (ASC) near Licata.

Near beaches where certain American units had landed, an American minesweeper engaged in intercept on an involuntary one-time basis. A carrier pigeon landed on the ship, and an alert sailor obtained the message, which was in Italian. In it, a division commander was reporting to his superior that the Allied forces were "overwhelming," and that they were unloading material, undisturbed, from hundreds of anchored ships. Upon receiving this bit of "intercept," Admiral Kirk determined that it was not too highly classified to share. He had it broadcast over the ship's loudspeaker system to all hands.[64]

The arrival of paratroopers of the 82d Airborne Division during the night of 9/10 July 1943 alerted General Guzzoni that the attack had begun. He telephoned warnings to subordinate commanders. The commanding general of the Herman Goering Panzer Division (General Conrath) lost his wire communications with XV I Corps (General Rossi) and the Sixth Italian Army before his reconnaissance patrols could report encountering Allied paratroopers. A radio message from Kesselring's Headquarters at Frascati informed him that a major attack was in progress.

The American forces were unable to maintain their schedule for inland advance. The troops ashore dispersed coastal defenders and seized numerous key points, but the beaches became a confused mess of broached landing craft and disorganized material. Antitank guns and tanks to combat counterattacking armored columns were too few. Only the most determined resistance by infantry units, with the aid of naval gunfire, turned back the enemy – in one case when the enemy was close to the beach. At one stage on 11 July the German defenders believed that their SIGINT had intercepted an Allied order for the U.S. 1st Infantry Division to return to the ships. The enemy came perilously close to sweeping along the Gela beaches and giving that division no choice in the matter.

Enemy air struck mainly at the landing operations off Gela on 11 July but also struck farther east. That night was very calm and clear, ideal for a second Allied airborne operation. It was equally suited to a heavy bombing attack by the Luftwaffe against the tired and jittery troops on land and the flotillas offshore. Unfortunately for the Allied airborne operation, its route of approach took its planes and gliders over Allied ships and antiaircraft batteries where they were not expected, where they were not identified, and where they drew fire of the kind appropriate for the enemy bombers which had just preceded them.

On D+ 2, however, when Kesselring flew from Frascati to consult General Guzzoni at Enna, the Allies were ashore to stay. Syracuse and Augusta had either fallen or been encircled. Airfields had become available to Allied aircraft. The U.S. Seventh Army faced a mountainous area through which General Guzzoni was shifting forces eastward, trying to stop Patton's advance and to reinforce the opposition to the Eighth Army. Kesselring concluded that delaying tactics alone remained feasible and so reported by radio to Hitler. The next day Hitler ordered such a defense, and on 14 July approved Kesselring's decision to send more German reinforcements. A German XIV Corps headquarters under the capable General Hans Hube, plus two more German divisions (1 Parachute Division and 29 Panzer Grenadier Division), and certain corps units were soon en route.

That night, Allied bombers destroyed Guzzoni's headquarters at Enna. He moved it to Randazzo, on the northern side of Mt. Etna, where General Hube also set up Headquarters, XIV Corps. All available mobile troops in western Sicily were called eastward to thwart the Allied plans.

Orders from General Alexander for the next phase of the Sicilian operations came to the commander of the Seventh Army on 13 or 14 July. While one corps of Eighth Army drove north along the east coast to take Catania and another corps moved via Enna and along the western slopes of Mt. Etna to the northern coast, Seventh Army was merely to engage those enemy forces that might otherwise oppose Eighth Army, but it was not to get tied down in a battle in southwestern Sicily.

General Patton sent a "reconnaissance in force" that, aided by air bombing and naval gunfire, took Porto Empedocle on 16 July and Agrigento on the next day. He then persuaded General Alexander to approve offensive plans for the capture of Palermo. At the same time, the German high command (OKW) directed that the defense of Sicily be conducted in such a way that the three German divisions [Herman Goering Panzer (which absorbed 1 Parachute Division), 29 Panzer Grenadier, and 15 Panzer Grenadier)] could be removed from Sicily. General Guzzoni concurred in General Hube's program to accomplish that and planned to withdraw his Italian formations at the same time. Fitting nicely into that scheme was the change in Eighth Army's plan of attack.

After finding progress across the Catania plain slow and costly, General Montgomery persuaded General Alexander to approve a shift of Eighth Army's main effort to the west of Mt. Etna, what he called a "left hook around the enemy's defense line." It took his main effort away from tank terrain into mountains, and far from the seaboard where he could, had he wished, have been assisted by naval gunfire; the new route would be beyond its range. The time required to get set for the new plan provided an opportunity for the opposing 29th Panzer Grenadier Division, as well as the paratroops, to be well deployed, and for the plans and means of German evacuation to be prepared.

Before Eighth Army's revised attack started, Seventh Army had entered Enna on 20 July and Palermo on 22 July; soon afterward it swept up all organized opposition in western Sicily, Trapani included. Though the port of Palermo was a handy target for enemy bombers and was cluttered with the results of German demolitions, it soon relieved the Seventh Army of dependence on southern beaches and miles of trucking for reinforcements or supplies.

Seventh Army was next brought into the revised Allied attack as a "prime spearhead" along the western and northern slopes of Mt. Etna. Beside the Canadians in the Eighth Army (moving via Leon-forte and Adrano) was to be the U.S. 1st Infantry Division (heading for Petralia and Troina). Along the northern coastal road were to be the U.S. 45th and 3d Infantry Divisions. To expedite the advance toward Messina by Seventh Army, U.S. Naval Task Force 88, under Rear Admiral L. A. Davidson, on 31 July 1943 began operations out of Palermo. While defending Palermo, it also furnished naval gunfire on request to troops fighting along the coast, provided transport and fire support for naval end runs around enemy defense positions, and ferried troops in order to relieve the burden on the coastal road. (Two cruisers and five destroyers were the escort and fire-support ships at the outset.) On 1 August the U.S. 9th Infantry Division arrived off Palermo in transports from Oran, and, after waiting out a heavy German dawn bombing attack on the city and harbor, landed and headed for the Troina area.

On 3 August the evacuation of Italian troops across the Strait of Messina began; on 10 August, the parallel German program (Operation Lehr-gang) started. Special intelligence released on 6 August disclosed major aspects of the German program and the orders to practice ferrying. On 8 August more SI gave Kesselring's report of two days earlier that the Germans would withdraw across the strait by stages which had already begun and would continue through 12 August. General Hube had set successive main lines of resistance and had fixed the times to pull back from one to the next.

Seventh Army tried three end runs to cut off use of the northern coastal road for retreat by the 29th Panzer Grenadier Division. The first, on the night of 7/8 August around San Fratello, where the U.S. 3d Infantry Division had been stopped for five days, was fairly successful. The enemy was not cut off. He pulled back eastward, probably as much because of the loss of Troina, at the inland end of that line of resistance, as because of an unhinging at San Fratello. The second, on 10/11 August, to Brolo, was less satisfactory. The enemy learned from his own SIGINT that it was in progress, and sent bombers against the Allied ships. The troops that had gone ashore unopposed were later attacked from both east and west, and were also bombed by friendly aircraft. The troops inland with which they were to link up were not close enough. The Brolo operation was unable to check the eastward withdrawal by the enemy during the night of 11/12 August; indeed it may have speeded up the retreat.

The third end run, on a larger scale and including paratroops was intended to overtake the enemy. He was then probably already in Italy across the Strait of Messina.

The occupation of Sicily was already complete when the principal U.S. Army officer in charge of communications security received examples of violations during the operation, examples taken from intercepted German reports that were graded as SI. Those American messages disclosed military information of significance. They revealed the participating commands, certain intended operations, places, times, and other details to the enemy. The route by which they had come to the knowledge of the officer commanding the Signal Security Agency precluded uninhibited use. It was a case of security impeding security.[65]

In the hotel in Taormina which had housed part of the German Air Force command in Sicily, records of its Horchdienst (Listening Service) covering a few days preceding the Allied assault landings, were found by Allied intelligence. A daily air situation report for the twenty-four hours before 0700 showed the efficiency and limitation of the German SIGINT service.[66]

After the severe defeat in Tunisia, the Axis coalition began to collapse. The Italian Army had lost so large a portion of its best troops there that Hitler proffered five German divisions for the defense of Italian soil. Two of them were already in Italy en route to Tunisia. Instead of three more, Mussolini agreed in mid-May 1943 that one more would be acceptable, but he required that all three in Italy be under Italian tactical control. He did not then think it prudent to have too many German troops in Fascist Italy.

By the time he had changed his mind and was ready to accept more, Hitler had recognized that the Italians might eject Mussolini from power and seek a separate peace, so the matter remained uncertain even when Mussolini was indeed overthrown.

The Allies occupied Sicily as a step toward accomplishing Mussolini's downfall and "knock Italy out of the war." What ensued after Il Duce's incarceration was foreseeable. The Badoglio government first sought to reach an armistice or peace between the Axis partners and the Allies. Hitler would have none of that. Under various plausible pretexts, German divisions moved into northern Italy without either the consent or the resistance of the Italians, and while preserving the amenities with their Italian brothers-in-arms, all but invested Rome in the guise of protecting it from Allied invasion. The Badoglio government, recognizing that Italy's interests demanded peace, then entered into clandestine negotiations with the Allies. The Allies, on 20 July 1943, had finally decided to move into the Italian peninsula from Sicily and Africa, employing the British Eighth Army, the new U.S. Fifth Army, and naval and air components that had just participated in the Sicilian landings. Whether the Allies would receive active assistance from the Italian Army or passive resistance, or might even have to rescue them from German reprisals, remained in doubt. After Mussolini's fall, more than six weeks passed before Allied troops first entered the Italian peninsula.

While the occupation of Sicily was progressing successfully and other operations against the Italian mainland were in prospect, it was apparent that some British "Y" units in the Mediterranean should be shifted to sites where they could be used more efficiently. By the time the invasion of southern Italy began, the strategic situation of the Middle East was more thoroughly altered. The Western Desert and Northwest Africa, as separate fronts, had merged. Northwest Africa was the base from which the campaign in Italy would be sustained. Intercept stations in Tunisia had to shift to Sicily or the Italian peninsula to be effective against weak and fading signals. "Y" resources in the Middle East needed pruning. If unified control of air and sea operations in the Mediterranean could be established, control of "Y" activities would seem to require parallel treatment. For the RAF "Y" organization, that would involve termination of one Wing, transfer of its personnel to other "Y" units or to other duties, and only a temporary prolongation of British involvement in "Y" service to the U.S. Twelfth Air Force.

Thus, while the Americans were nearly ready to meet the "Y" requirements of their ground and air forces in the Mediterranean area, the British were obliged to consolidate their Mediterranean "Y" resources, and to squeeze out unneeded, experienced personnel for employment in western Europe or in the Pacific.

Major Millard E. Rada, the commanding officer of the 849th SIS, went in July 1943 to GHQ Middle East for more information about British "Y" operations. He learned there what was done with German Army and German Air Force double Playfair encipherment and with Italian traffic in various systems and noted that AFHQ was better equipped for voice monitoring than was the British theater.[67]

[56] An incomplete set of minutes is to be found on Microfilm Reel 37-C of the Mediterranean Air Command records with others of AFHQ, at NARC, Suitland, Md. Also in AHA records.

[57] Memo from Chief SIGINT Officer, Mediterranean Air Command, to O.C. No. 276 Wing, O.C. No. 329 Wing, 15 Dec 1943, Subj: Liaison with French "Y" Service; Memo from MAC to DDI 4, Air Ministry, 5 Oct 1943, same subj.; msg from Chairman, London SIGINT Board, to Chairman, YNA Committee, 1 Dec 1943.

[58] Hq, 849th Signal Intelligence Service [NATOUSA/ MTOUSA], Operational History, (in NSA Hist. Coll) submitted to CSigo, War Dept (Attn: SPSIS), 27 July 1945. Preface signed by Lt. Col. M.E. Rada, SC, Co., 849th SIS.

[59] Humphreys, "The Use of ULTRA in the Mediterranean and Northwest African Theatres of War." (Oct 1945). Copy in NSA Hist Coll.

[60] See "Report on Visit to North Africa/Sicily, July 28th-August 23rd" 4 Sept 1943, by Major J.M. Browning, for the disposition of British field "Y" units. AFHQ Film A/52/2. (Most Secret).

[61] Minutes from A.C. of S., G-3, to SIG, 27 Mar 1943, Subj: Staff Information Radio Intercept Organization. AFHQ Microfilm Reel 58-I.

[62] Report of Signal Section, Seventh Army, "Historical Data and Lessons Learned in the Sicilian Campaign." 319.1 Box 34/11, AHS Recs.

[63] Garland and Smyth, Sicily and the Surrender of Italy, passim.

[64] John Mason Brown, To All Hands, 144, cited by Morison, IX 144 n. 26.

[65] See Folder: G-2 Corr, May 42-Sept 43. 20.1 in AHS Recs, A51–30, Box 1/72.

[66] Report CSDIC AFHQ A 191 (F.N. 644) 11 Sept 1943, from AFHQ Microfilm.

[67] Memo for Colonel Harold Hayes, Signal Section, AFHQ, from Major Millard E. Rada, SC, Commanding 849th SIS Battalion, AFHQ, Subj: Notes on Liaison Trip to Cairo, July 1–11 1943, 19 July 1943.