The third major amphibious assault in the Mediterranean area, that at the Gulf of Salerno, was much smaller than that at Sicily. It did not go wholly "according to plan," as the saying goes, and one might well ask, "What plan?" Not that it was unplanned, but, because the planning was subject to so many contingencies, it bristled with amendments of alterations of changes. Before the invasion of Sicily, the nearest that Allied leaders could come to an agreement on the next operation in the West was to charge General Eisenhower with drafting a plan for reaching certain conflicting goals. They would then review the plan and decide later what should be tried.

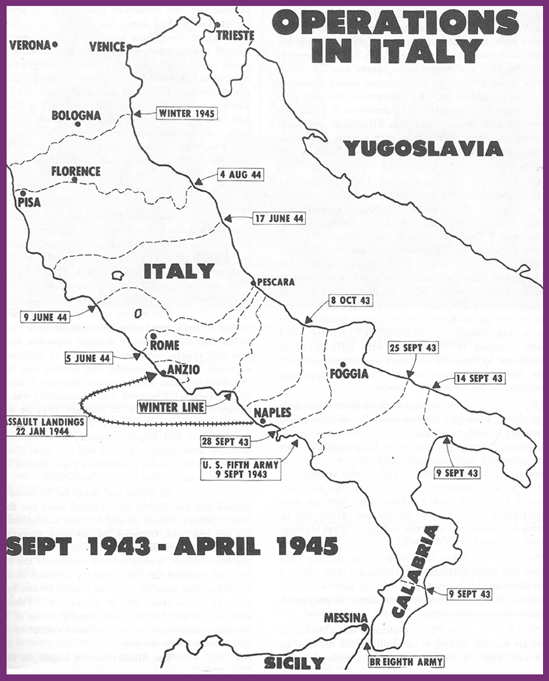

The operation that followed Sicily, they prescribed, must eliminate Italy as an adversary and tie down as many German divisions as possible, yet enable the Allies to make a cross-Channel attack in great strength beginning in May 1944. Part of that strength would have to be drawn from the Allied forces in the Mediterranean. Moreover, sealift and covering naval ships from the Mediterranean would be required for both a November 1943 amphibious assault in Burma, and a May 1944 invasion of France. The planners of AFHQ concluded, when Operation HUSKY (Sicily) was about to start, that its sequel would be governed by the rapidity with which the Allies succeeded in Sicily. General Eisenhower advised the Combined Chiefs of Staff (CCS) that he could certainly expect to cross the Strait of Messina and crawl through Calabria and that he might be able to enter Italy farther north at the Gulf of Salerno.

The Combined Chiefs of Staff believed he should plan to seize Naples, and when Mussolini fell from power on 25 July 1943, they approved an attack at Salerno with the resources already at the disposal of the Allied force. At Quebec in mid-August 1943 they confirmed that project, with the knowledge that the government of Marshal Badoglio was making overtures to the Allies for an armistice. Such a document was ultimately signed at Cassibele, Sicily, on 3 September 1943.[68] The decision at Quebec was followed by orders to British Eighth Army to cross the Strait of Messina and advance into Calabria as soon as possible in August.

In Africa and Sicily the Allied force accumulated men, ordnance, vehicles, and supplies for Operation AVALANCHE, which was scheduled to begin with beach landings on the Gulf of Salerno at 0330 hours, 9 September 1943.

The enemy was aware of the preparations but not of Allied uncertainties concerning destination, participants, and detailed plans that persisted as long as the role of the Italians remained in doubt. The Germans had already prepared plans for the military seizure of Italy as they had done for the military occupation of "Unoccupied France," almost one year earlier. While negotiations between the Badoglio government and the Allies were in progress, the German forces in Italy moved to positions enabling them to assume complete military control. The next question for the Allies was whether they could, in conjunction with Italians who would gain control of Rome, oblige the Germans either to pull back north of that city or be cut off in southern Italy. Until the last moment, such an operation was seriously contemplated. American airborne troops, they reasoned, could land on a Rome airfield that would be protected by Italian troops during their arrival, and be followed by seaborne reinforcements and support. All was kept in readiness to the last minute, but that airborne project was abandoned as was an airdrop previously planned – one designed to prevent troops in the Naples area from moving south to reinforce the defenders at Salerno.

The enemy did his best to shatter Allied preparations for embarkation at Bizerte. On the nights of 17 and 18 August, large bombing raids inflicted substantial damage there, and on the night of 6/7 September an even larger attack occurred. As the convoys heading for Salerno moved along the northern coast of Sicily, they too fought off persistent air assaults.

The Eighth Army's postponement of departure for several days gave the enemy forces in Italy more time to prepare for the landings. And the end of a period of radio silence tipped the enemy off, but Eighth Army troops encountered only token resistance when they came ashore on the peninsula on 3 September. A few days later, in trying to run along the coast to block retreat, they had the misfortune to approach the shore just as a German column was rolling by. The column stopped, swung into action, and inflicted considerable damage among the boats before resuming its withdrawal.

At the Gulf of Salerno, early on 9 September 1943, the Fifth Army intended to land 55,000 troops, using about 450 ships, and 250 landing craft, to establish a beachhead and to bring in 115,000 more men for an advance to Rome. On some of the approaching ships men heard the BBC announcement of the Italian surrender on 8 September 1943, inducing a wave of misplaced optimism. Despite the many reasons for believing the invasion was expected by the Germans, Fifth Army planned to begin its landings at first light without preparation fire from the ships, lest the bombardment eliminate surprise.

A few hours earlier the king of Italy, his premier, Marshal Badoglio, and his chief of the Comando Supremo, General Ambrosio, barely escaped from Rome. The German plans for seizing military control and disarming Italian forces went into effect. The 2d Parachute Division and 3d Panzer Grenadier Division in the vicinity of Rome acted under orders of General Karl Student to disarm the Italian troops. As the Italian field commanders pulled back toward Tivoli, Germans occupied the headquarters and captured many Italian generals and other officers. Hitler expected all Italians to be treated as prisoners of war. Kessel-ring, who doubted that the Italians would defect from the Axis, was mainly concerned with the need to get unimpeded access to Rome at once for General Heinrich von Vietinghoff's German Tenth Army in the south, and was willing to allow his former allies to stack their arms and disperse. Rome he agreed to treat as an "open city."

For a day or so, an Allied airborne attack there was a subject of some anxiety, but the lines to German troops in southern Italy remained open. The Italian people, deprived of leadership – either political or military – made little difficulty for the Germans.

In accordance with the armistice terms, elements of the Italian Navy tried to sail to an Allied port. Many succeeded but almost fifty combat vessels were destroyed in Italian ports, or by air attacks while en route. German forces also overcame Italian bases in the Aegean Islands. Certain captured Italian officers were handed over to the new puppet government, headed by Mussolini, after his rescue on 12 September. They were then put to death.

For Operation AVALANCHE at Salerno, the Allied Force used the American Fifth Army in its first campaign. The first American troops to go ashore were the Fifth's 36th Division. That division was part of a large array, neither wholly American nor wholly new to amphibious operations. Unlike the dispersed beaches of Sicily, the Gulf of Salerno faced a crescent strip of sand at the edge of a rolling alluvial plain enclosed within swiftly rising hills in a vast amphitheater. The streams that meandered through the plain, especially the Sele River and its tributary, the Calore, were too deep and wide to cross except by bridges. Fields and orchards crowded the plain, but most dwellings were on higher ground around the edges.

The attacking force was opposed by the 16th Panzer Division, deployed a few days earlier in time to get set for an invasion from the sea. Although thinly spread, they had prepared strong points to cover the approaches, beaches, and exits with machine gun and artillery fire and had mined the sea approaches and mined and wired the beaches themselves. Tank traps and batteries of mobile antitank guns would limit Allied armored support for an infantry that might succeed in getting off the beach. Antiaircraft gun positions were made ready. German tanks would move to danger points above the beaches.

Against those preparations, the Allies sent an Anglo-American naval force commanded by Vice Admiral Henry Kent Hewitt, veteran of Operations TORCH and HUSKY, who was aboard the USS Ancon. His armada divided into two Anglo-American attack forces, of which the northern had a Royal Navy commander and the southern, an American.

The U.S. Fifth Army, under Lieutenant General Mark Wayne Clark, consisted of the British 10 Corps, under Lieutenant General Sir Richard McCreery, and the U.S. VI Corps, under Major General E. J. Dawley. Three battalions (1st, 2d, and 4th of U.S. Rangers) and a British Commando Unit formed a part of 10 Corps, which contained the British 46th, 56th, and (in reserve) 7th Armoured Divisions. General Dawley had the American 36th and 45th Divisions in the assault and the 3d Infantry Division in reserve. In Sicily, the 82d Airborne Division waited in Army reserve.

The landings were to be supported by both carrier-based and land-based aircraft. Two fleet carriers of the Royal Navy and five small carriers would endeavor to protect the ships; the XII Air Support Command (Brigadier General E. J. House, USAF) of the Northwest African Air Forces would provide tactical air support in the battle ashore. Allied fighters from Sicilian airfields could operate over Salerno for only about twenty minutes before turning back with just enough fuel to get home. An Italian airfield at Montecorvino near the inland edge of the 10 Corps' sector was therefore a major D-Day objective.

The goal of Operation AVALANCHE was to occupy the small harbor at Salerno, the Salerno plain, the airfield at Montecorvino, and the road and railroad center at Battipaglia, nearby. In the steep-sided mountains between the Gulf of Salerno and the Bay of Naples to the north, the Allied Force intended to occupy the passes and adjacent heights. Firmly ashore, the Fifth Army would wheel left through those passes and over roads farther inland to capture Naples. After clearing the port at Naples of the expected demolitions, Fifth Army would bring in the reinforcements and supplies necessary to reach planned totals of 225,000 troops, 34,000 vehicles, and 118,000 tons of material.

A beachhead line to be reached, if possible on D-Day, ran along the hills ringing the plain. It embraced Vietri and Salerno on the north, Battipaglia, Eboli, Persano, and Ponte Sele in the center, Agropoli, Paestum, Capaccio, Albanella, and Altavilla, with an adjacent Hill 424, in the southern sector.

Like other amphibious assaults, AVALANCHE might have begun a race to establish stronger forces at key inland points. Instead, the 16th Panzer Division was there to greet the landing craft of the Italian surrender on on their way in, and to subject the troops of VI Corps and 10 Corps to a harsh reception. Next, it became a struggle to occupy and hold, or if driven away, to return and hold, key areas while opposing reinforcements approached. Lastly, it was a contest to strike weary troops, dispersed at various vulnerable points on the flanks or along the corps' boundary, with stronger troops concentrated to attain superiority in numbers and fire power.

On 9 September 1943 the Fifth Army got ashore despite the preparations to stop them en route or on the beaches. The enemy used his prepared positions plus his mobile tanks and artillery batteries in such a way as to make impossible any deep inland penetration. At the extreme left, a force of U.S. Rangers and British Commandos developed a separate beachhead on the steep-sided Sorrento peninsula, and got control of certain passes through the heights. At the right, elements of the 36th Division got to Paestum and Capacclo. But in both 10 Corps and VI Corps zones, the advance was not deep, and retention was possible only because the enemy's tanks had been neutralized or destroyed by naval gunfire, by two battalions of field artillery carried to the dunes by amphibious trucks (Dukws), and by resolute infantry armed with bazookas and grenades.

The British 10 Corps landings were preceded by shelling and rocket fire on the beaches south of the port city of Salerno. Their landings may thus have been less disrupted than those of VI Corps, but the enemy fought hard to hold them from access to the Salerno-Naples routes.

General von Vietinghoff, commanding the German Tenth Army, had two related missions. He had to hold the way north open for the 26th Panzer and 29th Panzer Grenadier Divisions in Calabria. He had also to stop Allied Fifth Army where it could later be destroyed, as soon as he could assemble superior strength. He called back the two mobile divisions from Calabria, where they had been obstructing the advance of British Eighth Army, and he summoned from the Naples area the Hermann Goering Panzer and 15th Panzer Grenadier Divisions. They and other formations moved toward the passes leading to the Salerno plain. Part of the 29th Panzer Grenadier Division was near enough on 9 September to begin assuming positions on the battle line before daylight. So Vietinghoff that night brought to the northern sector various units facing VI Corps. Fuel shortages slowed the movements of the 29th Panzer Grenadier Division, which straggled in during the next two days. The effect was to minimize opposition to General Dawley's VI Corps on the second day (D+ 1).

On 10 September 1943 Dawley brought in his floating reserve, while the leading troops on the right reached the hills, and in the center started a push to Ponte Sele. The next day, the 36th Division extended its hold to all heights from Agropoli on the extreme right to Hill 424, near Altavilla. At the same time, the 45th Division took over the left sector of the Corps zone, which was enlarged northward beyond the Sele River. The narrowing of the British 10 Corps zone permitted stronger British thrusts to take Montecorvino and Battipaglia and was an adjustment to the presence of more of the enemy in that zone. Salerno and Montecorvino were taken, but enemy artillery fire denied their use to shipping and aircraft. Around Battipaglia the battle surged in and out of the town.

By the night of 11/12 September, the situation looked favorable to the Allies. They were ashore to stay. The enemy's reinforcements might make an advance to Naples more difficult but did not seem to have brought about more than local counterattacks. Vietinghoff, however, did have a chance to strike back before the British Eighth Army arrived near enough to draw German formations away from Salerno. On 12 September he showed growing power in action after action.

To help provide effective air support during the amphibious phase of Operation AVALANCHE, SIGINT parties were placed aboard the headquarters ship, USS Ancon, and two British vessels, H.M.S. Euryalus and H.M.S. Palomares. Ancon was equipped with an elaborate system of telephones, teleprinters, and pneumatic tubes between the offices of various commanders, the staff operations rooms, and message centers. An RAF flight lieutenant and three Royal Navy seamen radio operators were reinforced by a voice intercept team consisting of an American 1st lieutenant, an RAF sergeant interpreter, and three American enlisted men. The four Americans were from Detachment "B,' 849th SIS. All were fluent in German but only the officer and the interpreter were familiar with German Air Force voice communications during combat operations, and the latter had been obtained luckily at the last moment before embarkation, as an exchange with the party on Palomares.

At Salerno the RAF adopted a method of distributing SIGINT that had proved successful during the invasion of Sicily – a broadcast from Malta of pertinent SIGINT based on the much wider intercept coverage possible at the fixed station in Malta. This time, the material that came via Royal Navy channels was slow in arriving. The broadcasts were not heard distinctly. After the first three days, the unit therefore turned to a parallel broadcast from RAF 329 Wing at La Marsa, Tunisia which could be heard fairly well. The wide intercept coverage at La Marsa that supported production of SIGINT enabled that station to advise, through the unit on Ancon, the commanders at Salerno concerning the state of German Air Force units within striking distance. As Allied countermeasures weakened enemy air, SIGINT picked up a report to a higher headquarters by the German command at the Foggia airfield that a considerable number of JU-88s and DO-217s were there. Soon Allied bombers hit that target, and commanders at Salerno realized that the diminished German air activity would not soon revive.

"Y" from Ancon was a means of offsetting the Germans' misuse of the same frequency employed by the Allied Fighter Director Officer. Their "phony" air raid warnings could be counteracted by prompt recognition.

The team from Detachment "D," 849th SIS, had two receivers that had to be manned continuously. Contrary to expectation, they found that even night bomber pilots broke radio silence when over the target area and, even during the last stage of an approach to it, kept asking if the target had been sighted. Radar frequently noted an approaching flight, but voice intercept confirmed the nature of the enemy formation. Moreover, radio interference from transmissions on the command ship affected radar more than it did the SIGINT radio receivers.

Voice intercept materially helped the air defense of the ships and beachhead. The communications of fighters, fighter bombers, bombers, and reconnaissance aircraft became readily distinguishable. The fighter pilots talked the most, even though obviously aware that they might be heard. Before combat with Allied aircraft, the leader of the formation gave orders to the other pilots, usually prefacing the orders with word of sighting an Allied plane that might be entirely unaware of being seen. That enabled the Allied listeners to pass a warning to the endangered Allied pilot. Frequently the German pilot, upon seeing an Allied plane, would report his own altitude and that of the one observed. In reporting to controllers or other aircraft in flight where a pilot was, he also sometimes used a German grid system known to the SIGINT team, at other times a visible landmark which the team learned to recognize. The pilots used callsigns that permitted a close estimate of the size of a formation.

A German pilot having engine trouble usually reported that he was turning back to base; such an aircraft was therefore often vulnerable. When fighters reported that they had dropped their extra gasoline tanks, Allied aircraft could be warned that the enemy aircraft might become more maneuverable in any impending encounter. If a pilot reported that his gasoline supply was down to a certain level, that often indicated that he was going to turn back to base with an amount calculated to get him there. If verbal air reconnaissance reports were heard, the information was presumably to be used by a formation perhaps already airborne, and if no such reports were heard, it might indicate a night bombing to come. The talk between bomber pilots about their targets occasionally disclosed how thoroughly informed the enemy was about shipping, as in the case of USS Ancon and later, H.M.S. Palomares, which controlled the carrier aircraft committed to supporting Operation AVALANCHE. Once the "Y" party had learned which callsigns and frequencies to watch, it could give about twenty minutes advance warning of a bombing attack on the ships. For about five days, the alerts brought response from Royal Navy Sea fires and other aircraft. Then, as the Allied planes were "worn down," the enemy began getting through to target shipping and the warnings went to ships' skippers.[69]

Elements of three incoming German divisions had been committed at Salerno by 12 September. For a time it looked, before that day began, as if the Germans might have decided to withdraw, having lost the race. British 10 Corps had gotten the enemy out of the town of Salerno and its port and off the airfield at Montecorvino, even though both remained under enemy artillery fire and were unusable. VI Corps had almost reached Ponte Sele, and held Altavilla and Hill 424. But on 12 September the course of the battle reversed. The enemy's reinforcements drove both 10 Corps and VI Corps units from their more advanced positions. As an offset to those setbacks, the U.S. Rangers on the 10 Corps flank near Castella Mare opened to the enemy a disturbing possibility of an Allied advance on Naples along the coast. U.S. engineers completed the preparation of air landing strips near Paestum and Salerno. During that night, in anticipation of enemy pressure in the zone between 10 Corps and VI Corps, General Dawley shifted battalions of the 36th Division to that flank.

General Clark, while on the Ancon, was in touch with GCCS via Admiralty channels and thereafter via a Special Liaison Unit with the Fifth Army CP ashore. Special intelligence was thus available before and during the landings. Information concerning the German strength in Italy was known, though German intentions there were obscure, perhaps because they were not definite until the Allies had been ashore more than a month. Intelligence showing the tactical disposition of the German ground formations that might oppose the landings was late in arriving. Cryptanalytic difficulties delayed a report from GCCS until the morning of 10 September, identifying general locations of some elements of the German Tenth Army. After Kesselring's first situation report to OKW had been sent at 2200 hours on 9 September, GCCS could send its import to General Alexander only a little more than one day later. Subsequent SI gave advance notice of enemy reinforcements and their disposition and of the tactical plans for counterattacks.

For the first two days, the German Air Force provided a relatively moderate resistance to the invasion. Bombing of the ships suddenly increased on the night of 11/12 September, when eighty-five hits by rockets and radio-controlled glider bombs occurred. During the afternoon of 12 September, General Dawley began strengthening his left flank by shifting all of the 45th Division north of the Sele River, leaving the 36th Division with thirty-five miles of front to cover. That afternoon, both General Clark and General House moved their command posts ashore. Ancon, known to be a special target of German bombers, was released only to be recalled when almost at Algiers and was then kept at Salerno until 19 September. Navy planes began using an airstrip near Paestum. While those actions on 12 September may have been based on Allied confidence that Fifth Army was ashore to stay, on 13 September the enemy's success in blocking Allied seizure of inland objectives, and in launching counterattacks that regained lost ground, led Vietinghoff to believe that the Allied invasion had stalled before gaining a firm lodgment. Partly on the basis of German SIGINT, he actually believed for a time that the Allies were preparing to pull out. How else could one explain the gap he had recognized between British 10 Corps and U.S. VI Corps? He therefore prepared his strongest counterattack to exploit that avenue to the beaches.

The enemy had enough new power on 13 September to frustrate Allied attempts to regain Hill 424 and Altavilla. His main effort was a heavy armored counterattack down the center near the Sele River. After almost wiping out American infantry in its path, his tanks ran onto a salient bounded by the Sele and Calore Rivers at their junction, perhaps expecting to use a bridge there that had been demolished. Facing that narrowing area were two battalions of field artillery and other elements of the 45th Division. Converging fire struck the tanks as they reversed their course.

The night of 13/14 September was a time of intense effort by Fifth Army. Aware of the German intentions and tactical plan, the Fifth Army's Staff Information and Monitoring Company (SIAM) Service intercepted a message early that morning in the 45th Division's traffic that said: "Fifth Army expects a coordinated attack this morning, possibly northwest from Albanella or south from Persano."[70] The Allied command brought over Fifth Army's reserve, the 82d Airborne, in three sections. The first were dropped that night. The second came by air, and the third by sea on the 15th. The 3d Infantry Division was alerted for transfer from Sicily by 18 September. General Alexander killed an idea that General Clark had discussed with Admiral Hewitt as a possible maneuver, should the enemy's success require it. That was to shift by sea the troops of one corps into the zone being defended by the other. Instead, he encouraged the Fifth Army in its plan to give up some ground for the purpose of establishing a shorter and stronger defense line and to put into the line as reinforcements not only the newly arrived paratroopers but also all available service troops. They were to reinforce 10 Corps right and the VI Corps left, where the enemy's attack was ultimately contained. In part that was accomplished by stalwart resistance at the Allied defense line. The enemy's maneuvers could not have suffered from learning, from a 36th Division message sent in the clear at 1120 hours: "CUB need 57mm ammo at once."[71] In part successful defense came from heavy naval gunfire and from stepped-up air bombing further inland on concentrations of enemy armor and troops. Particularly in the area near Bat-tipaglia and Eboli, the enemy found it costly to mount his thrusts. At the beaches and above the ships the air superiority of the Allied force was unmistakable.

By 15 September the enemy had accomplished the first of Vietinghoff's missions, and had concluded that any opportunity to drive the invaders off the beachhead had gone. While the German high command weighed the merits of defending south of Rome or farther north, the German Tenth Army began a slow withdrawal, hinging on the passes at the base of the Sorrento peninsula. It retreated to the northern bank of the Volturno, relinquishing Naples and the surrounding area to the Allies.

Enemy air attacks on the ships offshore, some of them over the horizon from the beachhead, came to a climax on 15 September with the crippling of H.M.S. Warspite. That battleship had been sent, in response to Admiral Hewitt's request, to provide naval gunfire far inland and had contributed some fifteen-inch shells to the devastating cascade near Altavilla. Radio-controlled glider bombs, however, scored two hits and two near misses that required that the battleship be towed back to Malta.

The "Y" parties on Ancon and Palomares were convinced that the glider bombs were being dropped from a higher altitude during lower-level diversionary attacks by other aircraft. When alerted, the Allies put aircraft still higher to terminate the practice. The next day they brought down two of the German bombers, and that success coincided with a general diminution in enemy air activity. He no longer could seriously affect the Allied operations ashore by interfering with the ships.

On 21 September the U.S. 34th Division began landing over the Salerno beaches rather than in the port of Naples as originally scheduled. A week later, as a storm suspended operations at the beaches for several days, the invaders found the enemy nevertheless releasing his hold on the passes and moving north. Naples was entered on 1 October by Fifth Army advance elements, while the Allies also gained control of Foggia. On 14 October unloading shifted from Salerno beaches to Naples. Meanwhile, the Fifth Army reached the south bank of the Volturno River.

Kesselring believed that the Allies could be held south of Rome indefinitely by using the topographic features and by building a series of major defense lines, of which the first would run across the peninsula through Mignano, ninety miles south of Rome, and the second, through Cassino, about twelve miles closer to the city.

Enemy tactics in the mountainous terrain made astute use of the limited road net, the vulnerability of stream crossings, and the advantages of ground observation points and sheltered artillery positions. Allied mobility was negated by mines, demolitions, and prepared fields of fire that obliged the attacking troops to make wide swings around road blocks, to construct their own bridges, and to engage in endless outflanking maneuvers on foot before a stretch of narrow road could be opened for vehicles.

As the Allies were about to cross the Volturno, the Badoglio government formally declared war against Nazi Germany. Italy became a cobelligerent, not an ally.

German troops on Sardinia were meanwhile moved to Corsica, and thence to Leghorn, while the battles in the south were in progress. They were then marched to the area southeast of Rome to reinforce the opposition to the British Eighth Army.

In the light of special intelligence, the Allies had begun operations in Italy expecting that the enemy would quickly relinquish the peninsula as far as the northern Apennines but would hold there in a prepared defense line shielding the Po Valley. Resistance in the south to gain time enough for construction in the north could be expected. The Allied objective at first was to liberate Rome, and they doubted that the Germans would make a stand south of that city. When they did just that, doubts emerged that the liberation of Rome would be worth the costs, but those doubts passed, and eventually it began to seem desirable to establish Allied control of the Po Valley.

Three weeks after landing on the Salerno beaches, the Fifth Army was in Naples. One week later it had reached the Volturno River. According to the schedule of withdrawal to a strengthened line of prepared defenses, the Germans pulled back from the Volturno toward the "Gustav Line" along the Garigliano-Rapido Rivers. It took the Allies several more weeks to break past an intermediate "Winter Line" and to advance through prominent hills and higher mountains. Hitler, after his initial uncertainty about a proper point at which to stop an Allied advance, on 4 October 1943 reached the conclusion that Kesselring, the optimist, had been right while Rommel, less hopeful, had been mistaken. The Germans would defend south of Rome, and continue to hold that political prize. Instead of entrusting the top command in Italy to his Army field marshal, he would give it to his Air Force field marshal. Army Group B in northern Italy was dissolved in November 1943. Its divisions passed to Kesselring's command. The Germans reasoned that only in the air would Allied superiority persist, and possibly that situation might also be reversed.

The first SIGINT teams with Fifth Army, during the amphibious assault, were provisional units placed on command ships to support air defense. On the second day of the invasion, the regular VI Corps unit came by LST from Sicily. It consisted of Detachment "E," 849th SIS, and about one-third, known as Detachment "R," of the 128th SRI Company. At the beach on 11 November that LST was hit by a shell that injured two men of the intercept company. The VI Corps unit covered medium-frequency nets between lower echelons, on which the traffic was about equally three-letter (T/L) codes and plain text, and between middle levels of command, in Playfair ciphers. The daily SIGINT report to VI Corps G-2 was sparse and insignificant until the action reached the area between Naples and the Voltumo River. Certain units could then be heard and their messages read, particularly the Engineer Battalion of the Herman Goering Panzer Division, the Reconnaissance and Artillery units of the 26th Panzer Division, and the Reconnaissance Battalion of the 3d Panzer Grenadier Division.

The Fifth Army had "Y" sections operating with army headquarters and each corps headquarters after Naples had been taken. On 16 October 1943 an Army Group "Y" Section attached to Fifth Army began DF operations. Colonel Edwin B. Howard, G-2, Fifth Army, reported then that the SIGINT service was well set up, and was producing a large amount of information quickly and accurately.[72]

When the campaigns in Italy began, German Army low-level traffic was increasingly transmitted on VHF links. In Africa, almost all of it had been on MF/HF (1–4 MHz). British experience there showed that an intercept unit was needed at Army headquarters level to maintain MF/HF coverage of enemy links that Corps units either could not hear or lacked enough resources to cover while monitoring targets of higher priority. The Army headquarters also needed an intelligence unit to guide collection, process the traffic collected, and interpret to G-2 the SIGINT obtained. But in Italy, as VHF traffic expanded and MF/HF traffic shrank, that arrangement had to be altered.

Since VHF transmissions were low-powered and line-of-sight, they could be heard usually only at forward sites by units working for Corps headquarters. Instead of reading current messages, the Army-level SIGINT units developed research, filing, and record-keeping techniques by which they reexamined traffic and logs in order to assist the work of the corps units.

Those changes attributable to alterations in communications technology were further encouraged in 1944 by new German signal security procedures. The resort to frequent and randomized callsign changes and the substitution in medium-grade traffic of Rasterschluessel ("Raster") for Playfair further complicated the situation.

Fifth Army tactical SIGINT was thought to be best obtained and used at the corps level by combining SRI detachments of 2 officers and 90 to 100 enlisted men with SIS detachments of three officers and fifteen enlisted men. The latter directed the intercept coverage, including search. The operators manned from eight to ten positions, normally enough to cover a corps front and to communicate by radio with an army detachment. The SIS element analyzed and interpreted the traffic. Its men were trained to recognize enemy networks, to break simple codes and ciphers and to translate and/or interpret decrypts. The senior SIS officer reported results to the corps G-2 either in daily morning reports or, if more urgent, by wired telephone.

For the first stage of the campaign from Salerno to Cassino, the Fifth Army Headquarters "Y" unit consisted of a detachment (3 officers and 115 enlisted men) from the 117th SRI Company teamed with the British 44 WTI Section (four officers and sixteen other ranks). In January 1944, after an overlapping period, they were relieved by the Headquarters Detachment, 128th SRI Company (Captain Shannon D. Brown, CO, one other officer, and 119 enlisted men) teamed with Detachment "A," 849th SIS (three officers and eighteen enlisted men). That combination remained the Fifth Army "Y" unit to the end of the war.

The VI Corps "Y" Unit, as we have seen, was a similar combination – a small detachment ("E") of 849th SIS (2d Lieutenant Sidney Reisberg) teamed with another detachment of the 128th SRI Company.

The II Corps "Y" Unit brought together a third detachment of the 128th SRI company (Lieutenant Francis H. Smith) and Detachment "H" of the 849th SIS. (Headquarters, II Corps, took command on 18 November 1943 of a sector of the Fifth Army's front.)

British 10 Corps was served by a British Special WTI Section and attached WTI Section.

849th SIS Mediterranean Theater (128th SRI), 21/2-ton camouflaged intercept van (Photograph from the NSA History Collection)

Overlapping coverage by the army and corps units occurred by design. Either for speedier service on certain matters to the Army G-2, or for guaranteeing hearability, or for the coordination and control of all corps-level units, some duplication seemed desirable. The army unit studied the summaries and technical reports by corps units, conducted research on enemy codes and ciphers, engaged in traffic analysis, distributed results to the corps units, and kept them from repeatedly duplicating part of each other's efforts.

After AFHQ had assigned the 128th SRI Company to Fifth Army, AFHQ retained no control over it. The 849th SIS detachments, on the contrary, although attached to the Fifth Army and completely under its operational control, remained under the administrative control of the 849th SIS at AFHQ. The detachments of the 128th SRI Company with the VI Corps and II Corps were only semi-independent, for they operated under corps G-2 control and received routine administation from corps headquarters, but they remained under Headquarters, 128th SRI Company (at Fifth Army) for matters involving personnel and equipment. An SIS officer assigned to G-2, Fifth Army, coordinated the operations of the Corps and Army "Y" units.

Headquarters, 15 Army Group, coordinated Fifth Army, Eighth Army, and 15 Army Group "Y" operations. The flow of technical information from research sections at Army Group aided the operations of Fifth Army sections immeasurably, in the judgment of the Signal Officer, Fifth Army.[73] Direction finding in Italy was accomplished at army level. While each corps "Y" unit in Fifth Army had one apparatus of British make, and found useful the single line bearings thus obtainable, it found that it could not manage DF nets. The 15 Army Group furnished the personnel for it to the two armies. On the Fifth Army front, three mobile DF teams in one net concentrated on enemy division and regimental traffic. After the DF data were processed at Army Headquarters, G-2, Fifth Army, sent the finished product to corps SIGINT units and corps G-2 sections.

Fifth Army controlled one SIGINT communications net; the Army unit itself, within a SIGINT net controlled by 15 Army Group, passed intelligence reports, technical information, and essential administrative messages. In the SIGINT section at G-2, a daily "Y" report, segregated from intelligence gained in other ways, was prepared. When the codeword PEARL (for low-grade decrypts) and CIRO-PEARL (for medium-grade decrypts) went into effect, G-2 had a "PEARL Section." Its daily intelligence reports tagged items for CIRO-PEARL, and in the case of the results of traffic analysis and direction finding, as THUMB 1 or THUMB 2, respectively.

Headquarters, Fifth Army, responding to instructions from AFHQ, created the 6689th Staff Information and Monitoring Company (SIAM), Provisional, which performed the functions of what the British Eighth Army had termed its "J" Service. Radio intercept operators in three corps and four divisional platoons monitored communications among Fifth Army units to detect violations of signal security that might benefit the enemy and to keep close watch on the positions, circumstances and intended actions of units at the front line. Their reports were intended to keep division, corps and army headquarters immediately aware of events at lower echelons and, at the same time, to keep the latter abreast of developments among the units on their flanks.

At the end of the war in Italy, the SIAM Service was appraised as efficient, desirable and "considerable," and if kept fully mobile, worth maintaining at one platoon plus one additional liaison officer with each division.[74]

The ability of the VI Corps "Y" unit to monitor communications of the Hermann Goering Division Engineers yielded early reports of demolitions and thus showed the pattern of German delaying tactics to be expected as the Fifth Army moved north. On 12 October the 3d Panzer Grenadier Division was identified as coming into the enemy line at the Volturno River. Its ability implied that it might be about to cover a withdrawal rather than to reinforce a longer stand at the river. By 15 October coordinates of the enemy's main line of resistance had been determined. The entire German Tenth Army had pulled back to that line, conforming to a schedule of withdrawal that gave time for the strengthening of the so-called "Gustav Line" along the Garigliano-Rapido Rivers and at Cassino. The 3d Panzer Grenadier Division had relieved the 16th Panzer Division so that the latter could be sent, at Kesselring's insistence, to face the British Eighth Army on the Adriatic side of the Allied advance. The relief had the effect of interrupting certain defense preparations at the Volturno and of weakening the opposition to be met by the U.S. 3d, 34th, and 45th Divisions as they crossed the Volturno and pushed up to the "Winter Line."

Another example of the merit of SIGINT in yielding intelligence from the area behind the enemy's main line came on 29 October 1943. The enemy was using a highway bridge at Mignano to move north. Allied bombers struck that morning with uncertain effect and were held available for a second attack. The VI Corps unit learned by noon from the Hermann Goering Division Engineers that the bridge was no longer usable, and that German road traffic had been rerouted. Early that afternoon the alternate bridge was also bombed out of service.

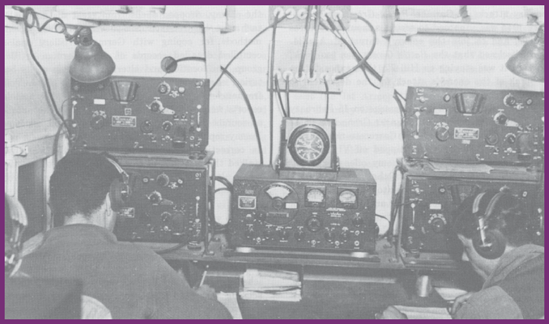

The American "Y" units in Italy moved in trucks and vans. Between 1943 and 1945 Detachment "A," 849th SIS, with the Fifth Army used a large trailer which had been modified by cutting out windows and a side door. The walls held shelves and maps. Along the sides were tables, a packing case converted into a desk with drawers, and a file cabinet. Gooseneck lamps, two electric fans, typewriters, telephone, teleprinter, and an M-209 converter formed part of the equipment used by the analysts and reporting personnel. Other detachments of the 849th SIS and those of the 128th SRI Company used two 2-1/2-ton trucks with solid walls and camouflaged canvas roofs at heights enabling men to stand under them. The vehicles would be parked rear-to-rear, connected by a platform to which a set of steps could be attached. Receivers were put on shelves and tables across the front and along the sides. Antenna lines and power and communication cables came in through openings. Each truck had an exhaust fan for ventilation. Some had screens over windows. Tents were pitched beside them.

One or more of the intercept units mounted an H-shaped antenna on a rotatable shaft running vertically through the roof, turned by a wheel at the base. Calibration of the circle was marked on the ceiling.

When an intercept unit could occupy a dwelling, it set up shop in relative comfort among a swirl of wires coupling the receivers with the antennas outside.

Early in 1944 the 849th resumed extensive processing and research at its headquarters in Algeria. The field center developed only after many of the personnel had gained experience working with SI-GINT units in Tunisia, Sicily, and Italy.

The Intelligence Branch 849th SIS was ready to undertake work on German Army and Air Force medium-grade (Playfair and double-Playfair) communications when months of preparation came to fruition in February 1944. A new Solution Section for that purpose then began operations. The preparations for it began with training in the United Kingdom of analysts who spent several months there becoming expert in Playfair analysis after preliminary analytic training in the United States. The first such group (three officers and twelve enlisted men) arrived in Algeria in July 1943. It was promptly added to a party from Detachment "B," 849th SIS (four officers and twenty-four enlisted men) and from the 117th SRI Company (two officers and ninety-seven enlisted men), all of whom went to Santa Flavia, Sicily, to develop their skills in covering the communications links on which medium-grade German Army traffic was being passed.

The second group (five officers and twenty-six enlisted men) reached North Africa in November 1943. In the following February part of that group (three officers and twelve enlisted men) was assigned to the new Solution Section. Almost immediately afterwards, the cryptanalysts who had been with Detachment "B" at Santa Flavia, Sicily, returned to work in the new unit. The table of organization (T/O) of the Solution Section contained "slots" for six officers and eighteen enlisted men for the rest of the war, and although the turnover of personnel was considerable, at the end of the Playfair period in November 1944, nine of the original thirteen enlisted men were still on duty there.

The Solution Section tried to analyze traffic in medium-grade cryptographic systems with the benefit of all obtainable collateral and all the collaboration available from other analysts. To anagram Playfair, an analyst needed familiarity with the usual addressees, signatures, routine formats, personalities, and other recurrent probabilities. Of secondary value were the frequency and combinations of bigrams. The British center for such work in the Mediterranean in 1944 was a Special Intelligence Company at Bari, Italy. Duplication of effort was reduced to a minimum, in part because of the slower delivery of traffic to the Solution Section. By the time the Solution Section could work on it, 7 SI Company had either broken the ciphers for that period or had turned to subsequent messages, leaving earlier ones unread. The American output was normally available from five to seven days after the time of interception.

The Intelligence Branch had a Laboratory Section with both photographic and chemical units. The latter tested for the presence of secret inks, working in Sicily and Salerno with the Censorship, and later with the CIC and the OSS. When the needed photographic equipment finally arrived, the photographic unit was able to assist others at AFHQ as well as the 849th SIS.

In January 1944 the Intelligence Branch established a new Traffic Analysis Section of sixteen enlisted men, who had come to North Africa after a training period in the U.K. The section controlled the intercept operations of a station (at L'ile Rousse, Corsica) that collected German Army traffic from northern Italy and southern France. The personnel of that station consisted of American intercept operators and traffic analysts who had previously been at Santa Flavia, Sicily, in the same group from which the cryptanalysts were to be taken for the new Solution Section of the 849th SIS in February 1944. Another detachment of the 117th SRI Company, one that had been working in Italy, rejoined the company in Corsica. The station there was then manned by 5 officers, 1 warrant officer, and 201 enlisted men of the 117th, plus 4 officers and 32 enlisted men attached from other units. Intercepted traffic went daily by air to Hamman Melouane.

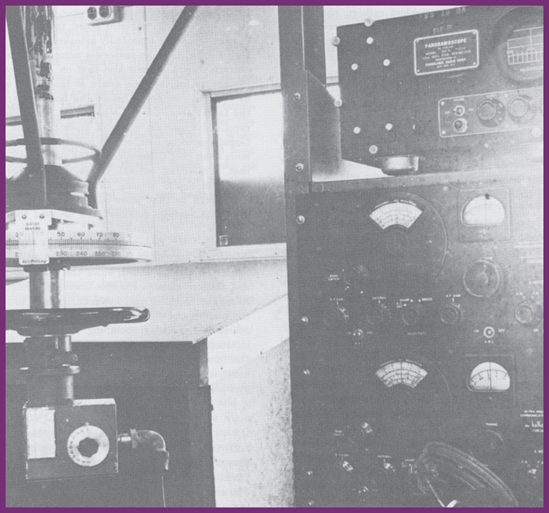

849th SIS Mediterranean Theater, interior of van showing DF controls and Hallicrafter receiver and Panoramoscope used by Detachment "D" (Photograph from NSA History Collection)

There the new Traffic Analysis Section examined traffic logs for repeats, transmissions, references in plain text, names of communicators, and other clues of value in reconstructing nets. The unit maintained files and researched callsign allocations. When predictable systems of allocation were replaced by random assignments, the Traffic Analysis Section focused on identifications by other means in order to assist forward detachments.

Both the Traffic Analysis Section and a new Coordination Section assisted the Solution Section. The former issued weekly reports on German ground radio networks and filed data on the Italian and Balkan nets in which the Solution Section was interested. The latter compiled data on order of battle, personalities, codenames, map references, and other matters relevant to Playfair traffic from Italy, the Balkans, and southern France.

About the same time that the other general command organization in the Mediterranean was changed, making it primarily a British responsibility, the RAF "Y" structure in that theater was altered. On 14 January 1944 Headquarters, RAF 276 Wing moved from Heliopolis, Egypt, to Conversano, Italy, and assumed control of all British RAF "Y" Units in the theater. It took over the "Y" broadcasts. Headquarters, RAF 329 Wing, which had been created to control such activities in the Western Mediterranean, became simply a personnel pool for assignments to duty in the Mediterranean or elsewhere. The ten subordinate RAF SIGINT Field Units were renumbered; some were to move up the peninsula as the front shifted, while others were to remain at Conversano and Caserta. At Conversano with Field Units 2 and 3 was Detachment "F," 849th SIS, and a party of intercept operators from the 123d SRI Company.

During the months of long-range bombing from bases near Foggia, such missions were accompanied by airborne voice interception teams. The logs of their collection efforts were studied in July 1944 for evidence of patterns in the defensive operations of the German Air Force; the study reproduced a fairly complete picture.

Locations and callsigns of the German controls were identified. From radar and visual observation posts, and from shadowing aircraft, it was noted that reports of the positions of Allied bombers were passed to a central controller, who relayed that information to fighter controllers. The latter got fighters airborne, assembled in formation, into and out of an attack, and then back on the ground. Also, if large numbers of Allied bombers and escorting fighters were reported to be approaching a target along several different routes, the controller would often confine himself to relaying observation reports leaving the choice of actual defensive tactics to the leaders of fighter groups.

It was also noted from these studies that as the Allies repeatedly attacked certain targets, they elicited German responses according to a regular pattern. SIGINT showed also that on several occasions the enemy had become aware of the Allied objective as early as two hours before the bombers arrived in the target area. On the other hand, when the enemy remained uncertain which of more than one possible target was to be bombed, he put fighters up to oppose more than one. Consequently, the Allies took a course that threatened several places, leaving the actual target in doubt as long as possible, and making a sharp turn to that place at the last minute. These feints successfully confused and delayed the enemy's response.[75]

Eventually studying the logs ceased to identify fighter units or to determine where specific fighter units were based, since the resort to frequent and random callsign changes prevented timely access to reliable data. It was, however, possible to calculate the numbers of enemy aircraft involved. Also, in the course of an Allied bombing mission, an airborne intercept operator could sometimes warn the leader of the formation that enemy fighters were approaching or that an intense antiaircraft barrage could be avoided by a change of course.

By 4 November 1943, having crossed both the lower and upper stretches of the Volturno River, the Allied force had reached the "Winter Line," which ran near several major Allied objectives. The advance took them through and over mountainous terrain, along dirt roads that the enemy had mined, and across streams where the enemy had demolished the bridges not previously wrecked by Allied air or artillery. Air support at that stage took the form of prearranged missions rather than attacks on targets of opportunity in front of Allied infantry. Fifth Army became exhausted during the first phase of its efforts to break through the "Winter Line." It broke off the attack in mid-November when the enemy was almost as tired.

It was possible for "Y" produced by VI Corps SIGINT unit to inform G-2 that elements of the 26th Panzer Division were reinforcing the 29th Panzer Grenadier Division in front of the U.S. 45th Division on 6 November. Three weeks later, the 26th Panzer Division was reported to be moving east to relieve the 16th Panzer Division on the Eighth Army front.

Both Allied armies girded themselves to renew the offensive. The U.S. 1st Armored Division arrived during November. A French Expeditionary Corps came, too. In the east, British Eighth Army sought to reach Avezzano, where it would threaten the Rome area from one direction. In the western zone, after getting through the "Winter Line," Fifth Army was to cross the Garigliano and Rapido Rivers and push generally northwestward along the Liri-Sacco River valley and Highway No.6. When Frosinone, about fifty miles south of Rome, had been taken, Fifth Army, it was thought, might make an amphibious landing at Anzio-Nettuno, thus threatening the enemy's flank and rear and hastening the Fifth Army's progress to Rome.

The attack by the Eighth Army fell short of its objective. The Fifth Army was also unsuccessful. The end of 1943 found it still south of the Garigliano and Rapido Rivers facing about two more weeks of slogging battles before it could even launch a crossing. The projected Anzio "end-run" had been necessarily shelved by the delay.

The "Y" units in Italy found that certain German divisions and lesser units were particularly valuable sources. The more mobile they were, the more likely they were to communicate by radio in simple systems involving minimal complication in encipherment. The basic codes stayed the same and all changes were quickly followed. The VI Corps SIGINT Unit faced some of the same formation successively between Salerno and the Volturno, again at the "Winter Line" and once more at Anzio. The Hermann Goering Division (especially its Engineer Battalion), the reconnaissance units of the 26th Panzer Division and 3d Panzer Grenadier Division, and the former's 93d Artillery Regiment-all proved to be valuable sources in action beyond the Volturno, as did the 764th Heavy Artillery Battalion. During the relatively gradual approach to the "Winter Line," they found few plain language transmissions on MF/HF but much more at lower echelons on VHF, both voice and radio. From battalions of the 26th Panzer Grenadier Division they obtained more and more. Then, at the "Winter Line" itself, during the stalemate in December and January, even though the enemy used wirelines to a greater extent, much material could be taken from MF/HF and VHF radio nets. Later, at Anzio they found the 764th Heavy Artillery Battalion and the 3d Panzer Division's Artillery Regiment each using its own type of letter-code on MF/HF nets, and the 65th Infantry and 4th Parachute Division, each with VHF nets differing from the other's. To the communications of German parachute divisions the Allied SIGINT producers felt greatly indebted.

The 15th Panzer Grenadier Division, which the U.S. II Corps Unit faced during the winter and the VI Corps fought during the breakout in May 1944, transmitted on MF/HF and used chiefly three-letter code; it was a generous source of SIGINT. During the Allied offensive of 11 May 1944 until the breakout, the II Corps "Y" Unit derived much of its material from the 71st and 94th Grenadier Divisions, particularly the latter's 267th Grenadier Regiment, which passed voluminous amounts of traffic in long, nonalphabetic, jargon code. Other elements of the two divisions indulged in much plain language and three-letter code on VHF links.

During the cold, rainy winter campaign of 1943–44, both sides were reinforced. By January, the German Tenth Army of fifteen divisions (so-called) along the Gustav Line faced the eighteen Allied divisions of the U.S. Fifth and the British Eighth Armies. Fifth Army included the U.S. VI Corps and II Corps, British 10 Corps, and the French Expeditionary Corps, while Eighth Army had British, U.S., and Polish divisions. The Fifth Army advanced to the Garigliano-Rapido River's southern bank along both sides of Highway No. 6. There the Allied advance again stopped. Successive attempts to open the way into the Liri River valley for exploitation by American armor were finally abandoned after the enemy had held on stubbornly to his dominating position at Cassino through March. British Eighth Army, after being checked short of Pescara, took over the eastern part of the Fifth Army front at Cassino.

Among Allied resources were sealift and navy escort for amphibious landings behind the enemy's main line of resistance. Such an attack at Anzio, in the western coast about twenty miles from the Alban Hills and thirty-five miles southwest of Rome, remained under consideration for many weeks.

The first plan of an Anzio operation called for a thrust toward the Alban Hills from the west in coordination with another from the south. It was reasoned that it might force the enemy to withdraw beyond Rome. The next plan entertained for a week in December 1943 was to draw German forces away from the Gustav Line to the Anzio beachhead and thus to facilitate the long-sought breakthrough. Failure to take Frosinone caused the first plan to be dropped. Inability to move far enough and fast enough, after breaching the Gustav Line, to establish mutually supporting drives by II Corps and VI Corps (at Anzio) caused the second plan to die. Since the sealift for an operation at Anzio was subject to the higher priority of a cross-Channel attack, for which many LSTs would have to leave the Mediterranean early in 1944, the chance to expedite the liberation of Rome via Anzio seemed to be slipping away as the new year approached.

By decisions in December 1943 and the following month, command in the Mediterranean area shifted from General Eisenhower to General Sir Henry Maitland Wilson. The British high command assumed the degree of responsibility previously held by the U.S. Joint Chiefs of Staff. The prime minister strove successfuly to bring about a two-division assault landing at Anzio in January 1944, at a time when, he hoped, the enemy might have to divert formations from the Cassino front in order to prevent the Anzio force from cutting the German line of communications to Rome.

Operation SHINGLE was executed by U.S. VI Corps under General John P. Lucas, who had relieved General Ernest J. Dawley as its commander on 20 September, just after the critical days at Salerno had ended in victory. The landings at Anzio were scheduled for 22 January, with British 1 Infantry Division on the northerly side and the experienced U.S. 3d Division, plus Rangers and others, on the right, or southerly side. After rehearsals near Naples, the landing force would embark there to make a surprise, night attack.

Kesselring was alerted by German SIGINT to the fact that the Allies were about to make such an attack somewhere, but he lacked air reconnaissance reports to suggest the probable place. Admiral Canaris, then head of the Abwehr (counterintelligence organization), on a visit to Kesselring's headquarters, assured Kesselring that no indication of such an operation in the near future had been ob- served. On 18 January Kesselring ordered two veteran divisions (29th and 90th Panzer Grenadier) and Headquarters, I Parachute Corps, to move from the Rome area to the mouth of the Liri River valley, there to relieve and reinforce the German troops facing the Fifth Army. On that same day, rehearsals for the Anzio landings turned out to be a sad fiasco; many Dukws and other craft, and the valuable, self-propelled 105mm guns that they otherwise would have borne ashore at Anzio, were lost.

At 0200 hours on 22 January 1944, 40,000 men and 5,200 vehicles started to land at Anzio Beach from 242 transport vessels and landing craft, escorted by minesweepers, destroyers, and other combat ships totaling 112. Tactical air support came from both British and American components of the Mediterranean Allied Air Force. The landings were not strongly opposed on the ground; by midnight the transports were 90 percent unloaded. Every three to four hours, however, German bombers struck.

General Lucas was expected to move his command inland as far and as rapidly as he could without becoming vulnerable to counterattacks. He would have to depend on daily convoys along the coast to maintain his force. Everything would be unloaded at a small port and on an exposed beach under bombing from the air and shelling from artillery. As the beachhead pushed inland, the line kept lengthening. To put the beach out of range of field guns and provide adequate area for dispersal, the line had to be long and thinly held. He doubted the possibility of penetrating far enough to interrupt completely the enemy's line of supply leading to the Gustav Line farther south.

The main opposition on D-Day came from mines in the lanes of approach and from mines planted in the sandy beaches, supplemented by artillery able to reach some of the shipping, and by aircraft that broke through Allied fighter defenses to hit beaches and some of the ships. During the next two days, the air attacks increased in strength and frequency and sought particularly to disrupt the influx of material. On D+ 3, despite bad weather that afflicted all unloading except within the small port of Anzio, enemy air pressed its program of curtailing the growth of VI Corps ashore while German troops assembled to contain the beachhead. Deliberate, savage German air attacks on illuminated hospital ships embittered the invading troops.

Generals Alexander and Clark came from Naples during D-Day to observe the action. General Alexander came back three days later to check on the progress toward the distant Alban Hills. He seemed then to approve the decision by General Lucas not to send raiding columns into the growing assemblage of German forces but to insure retention of his beachhead base against the threat that rapid German reinforcement was forging.

To cope with German Air Force attacks, the Twelfth Air Force had provided a considerable Fighter Control Squadron for the assault force and had put fighter-director teams on ships, as at Salerno. They found plenty to do. The results were mixed. On the ships, the fighter-director team on H.M.S. Royal Ulsterman was not kept informed of the movements by friendly aircraft, and the team on LST 305 specialized in defense by night fighters. The "Y" party with the latter was equipped to intercept traffic on VHF, inaudible during the periods from dusk to dawn when the control party was on duty, and audible only when the controllers were off. On USS Biscayne, the flagship, a fighter-director party kept in touch with others ashore. On the destroyer escort Frederick C. Davis, which provided protection for follow-up convoys, a "Y" team that had served on it as an air-warning unit before Operation SHINGLE, was able during the Anzio operation to earn a warm commendation, particularly mentioning T/5 Eric Marx of the 849th SIS.[76]

The small team from Detachment "D," 849th SIS, that went ashore on D-Day consisted of Lieutenant Pierre de St. Phalle and four enlisted men. They worked with the 82d Fighter Control Squadron.[77] The main body of Detachment "D" came later from Naples. The team first operated from its vehicle beside the road from Nettuno to Littoria. On 31 January 1944 it shifted to a site near a water tower north of the prominent Villa Borghese and placed an antenna where DF reception was better. Dependent for rations on the 82d Fighter Control Squadron, the team aptly named that unit GRUBSTAKE for coded calls. Keeping in close touch with GRUBSTAKE, reinforced by three DF operators and better equipped, the unit gained experience and reported important information for all Air "Y" service.

The team tested different methods and found some worth describing. By attaching loudspeakers to both receivers, the duty officer was free to telephone information at once to fighter control while the intercept operator controlled the set. The two receivers could be tuned to catch traffic transmitted on alternate frequencies. The DF set was also connected to a loud speaker; directional bearings were determined by the yield at the speaker rather than by using earphones and a carrier indicator. That arrangement improved the DF results.

When the unit began getting data from POW interrogations and documents that revealed the identities of many German units, their locations, types of aircraft, and state of training, its production improved correspondingly.

The "Y" detachment was able to aid the air warning service in determining the need for an air raid alert. It passed warnings to probable early targets of enemy air attacks as shown in radioed reports of enemy air observations.

Although General Lucas, the VI Corps commander, was eventually relieved, as his predecessor at Salerno had been, his decision to consolidate his hold on the Anzio beachhead before sending a column charging the enemy's line of communications seems today to have been the wiser course. The enemy reacted to the Anzio landings with amazing speed and power. General Clark and presumably General Lucas had known from special intelligence that the Germans had been preparing, by reorganization and reinforcement, to counterattack near Cassino and that no major German formation was in a position from which it could counterattack at Anzio before the VI Corps was well ashore. They learned, however, during the morning of D+ 1, that the enemy was moving quickly to challenge them.

Kesselring concluded that his line farther south could hold without the reinforcements that had just begun to take their places there. Headquarters, XIV Panzer Corps resumed the control of divisions it had assigned to the I Parachute Corps. That command, directly under Kesselring, was shifted to control other troops being sent to Anzio.

The enemy sent "pick-up" formations from the Rome area, called back others from the Liri-Sacco valley, brought one division from the Adriatic side and others, more slowly, from the Balkans and southern France. To control the buildup and launch the counterattack, Headquarters, German Fourteenth Army (General Eberhard von Mackensen) was summoned from Verona. By 25 January 1944 he was in charge at a command post near Rome. Four days after the landings had begun, elements of eight German divisions were already in place and five more divisions were en route. Special intelligence kept General Lucas aware in detail of the German regrouping.

VI Corps was ready on 30 January to expand the beachhead by attacking near the flanks. First, General Lucas sought to take Campoleone on the left and next, Cisterna, on the right. Campoleone was taken at considerable cost. The enemy, ready for the other thrust, ambushed and decimated the Rangers and checked the 3d Infantry Division short of Cisterna. The enemy's line had almost broken by the time VI Corps broke off the attack on 1 February and reorganized to meet the coming series of local German counterattacks and a German effort to drive the Allies back to the sea.

The Allied offensive began just before Kesselring believed his own forces could start their push. On 3 February Fifth Army learned from SIGINT how he had planned his main counterattack, and that he had hoped (in vain) to start it two days earlier.[78] Only on 15 February, however, did the suspense end and the big attack begin. It had become apparent that the enemy was concentrating near Aprilia for a drive from the northwest on a narrow front. Attacks elsewhere would be local and diversionary.

849th SIS Mediterranean Theater (3916th Signal Service Company) intercept van with double bank of receivers (BG 342 and BC 344) and the S-36 (VHF) in the middle (Photograph from the NSA History Collection)

By that time, VI Corps had about 350 tanks and 498 guns, and had established a good system of re-supply. Although medium tanks could not operate effectively on the semisaturated marshland and mud between the roads, immobilized tanks could supplement field artillery. Assembled enemy troops would find little shelter anywhere from concentrations of Allied artillery fire.

The German thrust down the main road between Albano and Anzio on 16 February drove a gap between British and American troops. Next day, a heavier ground and air attack exploited that gap. Overrunning the 2d Battalion, 157th Infantry, 45th Division, they caused the desperate battalion commander, under orders to hold at all costs, to warn the regimental commander of his plight. The tactical information that he radioed was quickly read by German SIGINT personnel and exploited by the attacking forces.[79] The enemy's attack was weakened by Allied artillery and checked by determined infantry. It came to a faltering stop on 20 February, still short of the "final beachhead line." If it represented the strongest drive that the enemy could mount, the Allies were at Anzio to stay.

Detachment "E," 849th SIS (nineteen personnel) and an element (seventy-nine personnel) from the 128th SRI Company, as the VI Corps "Y" Unit, were at Anzio. Its advance party, carrying three VHF receivers, landed on D-Day. The remainder came ashore with Headquarters, VI Corps, on D+ 5. As the enemy formations moved to face VI Corps, the "Y" team strove to identify and locate them. Differing characteristics of the communications procedures of divisions and artillery units made that problem easier to solve.

During General von Mackensen's preliminary attacks, a German battle group on 8 February 1944 was supposed to secure a mound known as Hill 72 and to join the enemy's thrust at Aprilia. SIGINT disclosed that the battle group was too weak and that it was staying on Hill 72, thus exposing the left flank of the enemy's attack for the defenders to take advantage of.

When a noon message on 15 February 1944 revealed that the 29th Panzer Grenadier Regiment had come into the line at Carroceto next to the 809th Infantry Regiment, it tipped off VI Corps to the imminence of a stronger enemy offensive there. On 20 February, the last day of that attack, the VI Corps Unit decrypted orders sent to the 105th FLAK Regiment to fire, between 1720 and 1750 hours, a total of 2,600 rounds on Allied troop concentrations along certain routes of approach. G-2 thus warned the troops at least one hour in advance of the shelling.

During the German counterattack, Major General L. K. Truscott, Jr., commanding general, 3d Infantry Division, became General Lucas's deputy commander. After it ended on 22 February, he relieved General Lucas as commanding general, U.S. VI Corps.

General von Mackensen made one more attempt. On 22 February 1944 he began regroup- ing for it, and SI disclosed that it would come on the other flank, along the axis of the Cisterna-Nettuno road. By the time it could be started, on 29 February, General Truscott knew what enemy forces would be committed and had regrouped his own formations. Allied air support was also primed. for it. By the second day, the enemy knew that this counterattack would also fail. As skies cleared on 2 March, Allied bombers struck behind his lines and Allied ground troops dispersed all attempts to penetrate the beachhead. Kesselring had already decided to go on the defensive both at Anzio and the Gustav Line.

In March 1944, since the Allies had found themselves unable to break through near Cassino and the enemy had proved himself unable to crush the Allied forces at Anzio, the situation on both fronts was a stalemate. That condition lasted more than two months, until 11 May. The opposing forces sparred and jabbed. The Allies reinforced the Fifth and Eighth Armies, regrouped, accumulated fire power, wore down the German Air Force, and by extensive training got ready for the May offensive.[80]

During the long stalemate, as before it, enemy artillery fire struck endlessly at targets throughout the beachhead. Protection was achieved by digging in, by camouflage and smoke. "Anzio Annie," nickname for any of the colossal railroad guns fired by the enemy, dropped shells from great distances. Detachment "E," 849th SIS developed some special methods for coping with German artillery fire. It compiled detailed records of each German artillery group, the location and alternate location of its batteries, each fire mission and the rounds fired. Voice frequencies were continually watched. All radioed reports were tabulated in order to verify the number of rounds fired and the ammunition still on hand. Enemy reports of Allied counterbattery fire were used as correction data for Allied guns, and as SIGINT stalked the positions of certain enemy batteries, they were ultimately broken up by hits and forced displacements.

The spring offensive for which the "Allied Armies in Italy" had been preparing was scheduled to start when it might have the effect of keeping forces in southern France away from the forthcoming cross-Channel attack. On the southern front, General Alexander's attack began with an unprecedented artillery preparation an hour before mid-night on 11 May 1944. On the Anzio front, the Allied offensive was timed to begin several days later, after reserves available to Kesselring might have been committed to holding the Gustav Line. Subsequent success in breaking out from the Anzio beachhead might then, by threatening to block the long, motorized lines of communications to German Tenth Army, contribute to the progress of the southern attack.

The Allies had extended the Eighth Army to cover a wider front from the Adriatic southwestward. It faced the hitherto impregnable Cassino- Monte Cassino section of the Gustav Line and the adjacent Liri River Valley. Fifth Army's French Ex- peditionary Corps, greatly enlarged to almost 100,000 men, was now ready to break into other mountainous parts of the enemy's defense system. From the Tyrrhenian Sea inland to the Minturno area was U.S. II Corps, consisting of the 88th and 85th Divisions; in II Corps reserve was the 36th Division. In the Anzio beachhead under VI Corps were British 1 and 5 Divisions, U.S. 1st Armored, 3d Infantry, 34th and 45th Divisions, and 1st Special Service Forces.

The enemy's Fourteenth Army at Anzio included two corps headquarters controlling eight divisions to contain the Allied forces and guard the coast north of Anzio. The German Tenth Army had two corps and ten divisions. In reserve were the familiar 26th Panzer and 29th Panzer Grenadier Divisions, the 90th Panzer Grenadier Division and, in the Leghorn area, the Hermann Goering Panzer Parachute Division.

Allied air superiority amounted to a ten-to-one advantage in aircraft. The German Air Force could manage only weak and infrequent strikes at the port of Naples and at the shipping off Anzio, while Mediterranean Allied Air Force (MAAF) had rendered the railroads unreliable south of Florence, and so had forced extensive resort to trucks. Along the coast Allied bombers struck enemy ships and ports.

The French Expeditionary Corps overcame desperate resistance in the mountains west of the lower Garigliano and immediately south of the Liri valley during the first eight days of the May offensive and broke through the Gustav Line. It helped both the Eighth Army on its right and the U.S. II Corps on its left. The latter also drove through the Gustav Line and captured Formia, Gaeta and Itri. Tactically, Allied success reflected accurate intelligence concerning the locations of enemy strong points, their artillery observation points, and the best routes for Allied penetration and encirclement. Strategically, the offensive quickly drew miscellaneous units to confront II Corps, after one German division there had been demolished, and attracted the 26th Panzer Division to try to stop the French Expeditionary Corps.

The enemy made a determined stand at Fico because of its importance in a defense line extending northeastward to Ponte Corvo, the next set of defenses beyond the Gustav Line. The French took Pico on 22 May. They had then advanced so far beyond the Eighth Army in the Liri-Sacco Valley that, for a time, General Alexander weighed the merits of swinging the Fifth Army northward to reach that valley. Despite heavy casualties, Eighth Army began crumbling the defenses it faced; so Fifth Army continued generally northwestward along the Tyrrhenian coast.

On 24 May II Corps was able to drive the Germans out of Terracina, where Highway No.7 ran along a narrow shelf between mountains and sea. That made it possible to link the two segments of Fifth Army by overland communications. And it enabled II Corps to bring more of its forces by land to join the 36th Division, which had gone to Anzio by sea, and to assume responsibility about one week later for pursuit of the enemy along Highway No. 6 to Rome.

By the time the Allied breakout from Anzio beachhead had begun on 23 May, the enemy was trying to bring the German Tenth Army back to the last prepared belt of defense south of Rome, that extending between Ardea near the coast to Avellano. It was not as strong as the Gustav Line had been but, south of the Alban Hills between Velletri and Campoleone Station, it was most formidable.

On 23 May 1944 General Truscott sent the 1st Armored Division, on the left, and the 3d Infantry Division, on the right, across the sector of the beachhead line held by the 34th Division, that between Carano and Conca. The objective was to take Cisterna, block Highway No.7 between Cisterna and Velletri, and control the approaches to the gap north of Cisterna between the Alban Hills and the Lepini Mountains. Cori, northeast of Cisterna, and Velletri, northwest of it, were to be separated by further advances toward Valmontone in the valley and to Artena, on the southern edge of the gap. Although Cisterna was strongly defended, it was isolated and captured, while Cori, and beyond it Giulianello, were taken.

The enemy's counterattacks were scattered and weakened by heavy Allied air attacks on jammed roads and by other factors that denied him opportunity to coordinate his efforts. During the fluid battle, Allied SIGINT was the main means of locating enemy units, though air reconnaissance noted concentrations and interrogation of prisoners yielded identifications. The enemy at one time was desperately trying to bring in armored reinforcements on the same roads that broken units were using to move in the opposite direction.

As Combat Command B, 1st Armored Division, headed for Cori on 24 May, a message sent by the German 105th FLAK Regiment divulged the location of a strong antitank barrier of mines and guns in the planned path of approach. Warning came in time to reroute the American force, which successfully eliminated the position and forced large numbers of enemy troops to surrender.

SIGINT also disclosed the enemy's reactions to Allied progress. An element of the German 715th Division reported at 0910 hours an Allied breakthrough near Cisterna on 24 May and its own withdrawal northward to Bassiano. At 1608 another report described the Allies as again attacking Cisterna from the direction of Privorno. Later that day the 105th FLAK Regiment reported that the Genzano-Velletri road, close to the Alban Hills, was impassable because of bomb craters.[81]