The complete defeat of the enemy in Normandy produced a situation in which the questions became: how much could he extricate from the so-called "pocket" west of the gap between Argentan and Falaise; and having saved what he could, where would he cross the Seine River; and where would he be able to establish a new line of defense? Haislip's XV Corps went to the Seine and wrested a bridgehead on the far side at Mantes-Gassicourt. Corlett's XIX Corps joined in an attempt to establish a second encirclement along the Seine, but most of the enemy was able to shift northward toward the Seine estuary and to cross there to the eastern bank. Once across, they moved along the coast. Other shattered German forces crossed the upper Seine and for a time may have thought that they could defend along such a river line as the Aisne-Marne or the Somme in conjunction with the German units that had crossed the lower Seine.

On 15 August 1944 the Seventh Army's invasion of southern France began, and during the remainder of the month, German occupation troops as well as combat forces withdrew from most of France. They continued to defend German possession of ports in Brittany and along the Channel. Unable to withstand Allied pursuit, the enemy appeared to be fleeing into the shelter of his fortified Westwall – that zone of pillboxes, obstacles, and barriers near the German border.

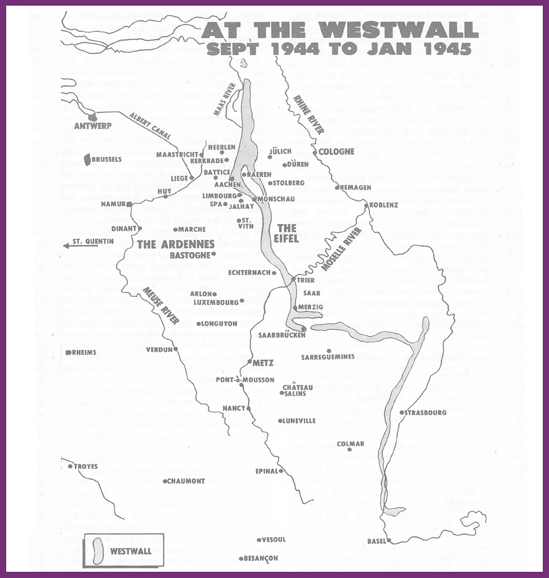

U.S. First Army moved along the Seine on the right of 21 Army Group and sped through northern France into Belgium and Luxembourg. XIX Corps on the left was next to the British. VII Corps was on the right, passing through places with names familiar to veterans of World War I. V Corps was involved in the liberation of Paris and then moved through the city and toward that part of the Westwall south of Aachen. The columns moved rapidly in long daily jumps, with skirmishes and small encounters but few substantial battles. As they reached Belgium, the VII Corps and V Corps then shifted so that the latter came up beside the XIX Corps, while the VII Corps crossed the Meuse and passed eastward in country that, in late December 1944, became the northern edge of the German Ardennes salient. The enemy's hasty retreat across France led to overconfidence among the Allies. They believed that the Germans were so demoralized and so weakened that they would not fight until within the Westwall, and that even there they would be readily overcome.

The pursuit in the north enabled American troops to head off and to capture or destroy thousands of the enemy and their vehicles in the renowned "Mons pocket," where bitter fighting in World War I had also taken place. Yet along the Scheldt, the Albert Canal, and the Meuse River, forces sent from Germany manned a line through which the retreating enemy passed to reorganize in its shelter, or along which they were able to take up positions because of the carelessness of Allied com-manders. Weary but exultant over the rapid advance that brought about the seizure of Brussels and Antwerp, those commanders neglected to control the bridges over the Albert Canal. All crossings were then blown up by the Germans. That costly mistake could have been attributed to inadvertence but another, of greater proportion, was the failure to interrupt the escape of enemy troops across the watery area between Antwerp and the coast. In a ferrying operation that took several days, thousands of the enemy slipped across the Scheldt and kept on behind the German line to join its defenders. At the same time, the enemy in effect extended his defense line onto Walcheren Island, and denied the use of the captured port of Antwerp to the Allies until they could gain control of the banks along the lengthy channel so that Allied ships could pass. It took until 8 November 1944 to clear the enemy from the sites menacing the Scheldt.

The enemy was able to thwart an Allied airborne and ground operation to gain the Rhine bridge at Arnhem. While the plan was risky almost to the point of being foolhardy, it was apparently bad luck that brought German panzer forces into the area where Allied gliders and parachute troops later descended, and inflexibility that caused the operation to proceed in spite of SIGINT warnings of the German forces there. German forces were able to oppose Allied movements and thus to overcome the men who had succeeded in seizing the Arnhem bridge and to regain control of it before Allied reinforcements could arrive to consolidate a defense and retain possession. German Air Force units also struck Allied troops concentrated at the nearby Driel railroad station to whom, for lack of any communications, no warning could be conveyed by a SIGINT detachment that had learned of the impending operation about three hours before it began.

In the end, the enemy's new main line of defense could be neither outflanked nor swiftly pierced. It took months more to reach the Rhine.

Although the main effort by the Allies remained that of breaching or circumventing the Westwall for a crossing of the lower Rhine, followed by the capture of the Ruhr's industrial complex, and then by a drive eastward across Germany's northern plains and northward to seize her ports, no such attempts could be made until Antwerp was operating as an Allied supply base. That could not begin until the port was rehabilitated and made accessible from the sea, conditions achieved during November 1944. Though Field Marshal Montgomery (as he became by promotion on 1 September 1944) believed that under his command the Allied ground forces could accomplish the early defeat of Germany by a relatively narrow invasion that carried to Berlin (and others supported that view), General Eisenhower believed that the enemy must be kept under strong pressure at many points without waiting for the mounting of such a spearhead attack as Montgomery advocated.

In October and November 1944, therefore, the U.S. Ninth Army moved its headquarters to Maastricht, Holland, and, as part of Bradley's 12th Army Group, launched attacks to push through the Westwall toward Cologne. With U.S. First Army (FUSA), it shared some the the hardest combat of World War II in reaching the Roor River valley trying to control the dams that could flood the area, and to break through to the east. Those efforts were not successful. The city of Aachen was captured. The Westwall zone was thus entered without being pierced. The battles inflicted heavy losses on both sides.

The detachment of the 3d RSM with the Ninth TAC became so alert to the sounds of radio telephones in German aircraft that they were able to recognize the noise of carrier waves when a pilot turned on his set even though he refrained from speaking. Their direction finders could pinpoint the aircraft and fighter-controllers were thus enabled to vector aircraft to vantage points for attacks. Claims to twelve victories were based on radio intelligence of this sort.

The enemy was known to have an uncommitted reserve from which a counterattack could be expected unless these divisions were used instead to stop the Allies in a resumed offensive. Preliminaries to a renewed U.S. effort to get control of the Roer dams, and thus to be able to retain bridging over the Roor once it had been crossed, began during the first week in December. U.S. First Army was about to strike again when on 16 December 1944 the enemy launched what Allied reporters called the "Battle of the Bulge."

During the pursuit, the Corps RI companies had found their arrangements for mobility put to a test that showed them to be generally effective. They moved by echelon so that intercept coverage could be continuous even during a move, and they were able to spot some of the enemy units, the temporary locations of CPs and supply or ammunition dumps, and the state of potential opponents. To achieve good direction finding usually required stops longer than proved practicable. The arrangements for consulting maps within a truckborne hut left something to be desired.

When a gasoline shortage required interruption of the Allied pursuit, FUSA was aware that enemy opposition was not far away. Their delaying road blocks and mines, blown bridges, and other harassing actions were about to be superseded by a firmer defense. The enemy was not going to rely on the shelter of the Westwall's semifortified positions as the site of his first shift from retreat to static defense operations. He was going to oppose the Allies in all approaches to the Westwall.

By 16 September 1944 the 3251st Signal Service Company (RI) with VII Corps was able to occupy a site across the German border at Kornelimuenster, where it worked for the next month. The 3252d company with XIX Corps, which moved eight times in September, settled at the end of the month at St. Pieter and remained there until 13 October. It then moved to Heerlen, east of Maastricht, where it remained for more than two months.

Haislip's XV Corps, which had gained and held the bridgehead over the Seine at Mantes- Gassicourt through which part of FUSA crossed in pursuit, was transferred temporarily from Third to First Army. When it reverted to Third Army and moved toward the Moselle, its RI company, the 3253d, moved on 9 September to Lusigny, southeast of Troyes, and shortly afterward, in a series of shorter moves, went another 150 miles to the upper Moselle valley. On 29 September 1944, when XV Corps left Patton's Third Army for General Alexander Patch's Seventh Army, the 3253d entered the Seventh Army's SIS together with the 117th SRI Company and its Detachment "A," which later became the basis of the 3260th Signal Service Company (RI) while operating with VI Corps.

The 3254th, attached to VIII Corps, Third Army, left that command temporarily in Brittany and worked directly under Signal Security Detachment "D" (SSD "D") at Mangiennes near Verdun. Early in October VIII Corps turned its responsibility in Brittany over to others and moved to plug a gap in the Allied line in the Ardennes area. The 3254th left Verdun and found a site at Houffalize from which to serve VIII Corps under FUSA until, on 20 December, it moved with VIII Corps to Third Army control during the Ardennes campaign.

The 113th Signal Radio Intelligence Company with FUSA moved successively to Huy on the Meuse, to Jalhay, Limbourg, and Battice, Belgium, while Headquarters, FUSA set up at Spa. The 118th SRI Company with Third Army stayed near Verdun as long as the campaign toward the Saar was restrained by supply problems and by the departure of XV Corps to join Seventh Army farther south. The 117th SRI Company, already with Seventh Army, reached a site near Vesoul on 20 September and moved to the Epinal area on 2 October. In September 1944 the 137th SRI Company, which had been assigned to HQ, Ninth Army, moved to the vicinity of Verdun and operated there and at Hollenfells, Luxembourg, under direction of SSD "D" until the Ninth Army was in a position to use its capabilities. When HQ, Ninth Army, opened at Maastricht on 15 October 1944, the 137th SRI Company set up at Valkenberg, Holland.

The Ninth Army was originally scheduled to control the XIII, XVI, and XII Corps. On 25 November 1944 the 3258th, attached to XIII Corps, began its move to Kerkrade, Holland, and a week later, the 3257th took a similar route to join XVI Corps at Heerlen the III Corps, however, went to Third Army without a SIGINT company of its own. The XIX Corps then came under Ninth Army, taking the 3252d with it. XII Corps had to borrow the 3256th from XX Corps during the Ardennes campaign, and only late in February 1945 got the 3259th to keep.

The 114th and 116th SRI Companies, assigned to 12th Army Group, were among the units using the Verdun area early in September. On 10 October 1944 the 116th shifted from Verdun to Bettem-bourg, Luxembourg, where it stayed until 20 February 1945. It did not pull back during the enemy's thrust through the Ardennes. On 8 November the 114th – after a month at Walferdange, Luxembourg – moved to Verviers, Belgium.

The 121st and 124th SRI Companies, trained for higher grade interception and analysis in the direct service of SID, ETOUSA, and SHAEF, came from England later. As we have seen above, the 121st operated at St. Quentin, France, from December to March, and the 124th at a site near Congy, France, through the winter. It was sent to Pont-a-Mousson, under HQ, 6th Army Group, on 4 March 1945 for the remainder of the war.

The speed of the Allied pursuit to the edge of Holland was surpassed by that of the Allied drive farther south across the Meuse to the Moselle River en route to the Saar basin. The opposition there was weak. But neither Allied advance could maintain the pace as distances from the supply ports lengthened. By 4 September a condition that, at various times in World War II, would affect armies and air forces on both sides brought the advance toward the Moselle to a temporary stop. Shortage of motor fuel obliged the Supreme Command to resort to allocations. To give enough to 21 Army Group, supported by FUSA on its flank, none at all was given to Third Army (TUSA) for a few days and after that only reduced amounts which restricted TUSA's operations. The enforced pause in September allowed the enemy to bring forward important strength, so that crossing the Moselle became much more difficult than it might have been a few days earlier. The enemy even tried to launch a strong counterattack that would forestall the linking up of Seventh Army with Third Army. He was frustrated by conditions that had induced him to make successive commitments piecemeal rather than to deploy overwhelming strength. His intentions were observed in SIGINT, as well as in other sources of intelligence, enabling the Allies to take effective countermeasures.

Two major developments changed the situation. Allied strategy for the future made the campaign toward the Saar a secondary effort. The main drive was to be that bound for the Ruhr, conducted by Montgomery's 21 Army Group, to which the U.S. First Army would provide flank protection. The Ninth Army was to come in between First and Third Armies. Since supplies were still brought to both Montgomery's 21 and Bradley's 12th Army Groups from ports far to the rear, the resources for delivery were insufficient to keep all offensives going. The pause from 1 to 5 September was repeated at the Moselle bridgehead from about 9 October to 8 November, though it was more a slowdown than a complete stoppage. The enemy was subjected to limited attacks instead of being given the usual indications that an opponent had gone over to defense, such as barbed wire, mines, and entrenchments, lest he release a portion of his forces from that part of the front to strengthen another. Patton instructed his corps commanders to continue making limited attacks, to keep a good line of departure for a renewal of the offensive, and to set up outposts and mobile reserves. Artillery batteries were to be ready to strike all roads likely to be used by the enemy.

As XX Corps headed toward Metz, running out of gasoline before its first objectives at the Moselle were attained, the 3256th Signal Service Company (RI), during the night of 3/4 September 1944, picked up an order from an enemy commander to a Reconnaissance Patrol Schellwitz to keep Highway 18 under observation. Later, by DF operations, the section of the road being patrolled was ascertained to be northeast of Longuyon and north of Longwy. XX Corps sent its own armored reconnaissance unit there and captured several prisoners from Patrol Schellwitz.

By September 1944 the 3256th Signal Service Company (RI), working with XII Corps, was at Nancy after completing a drive across France from Orleans. There Third Army traded blows with strengthened German forces until, after hard fighting east of Nancy, it could resume its advance in November.

While XII and XX Corps had been moving from the Meuse to the Moselle, XV Corps returned to Third Army command, after a period under U.S. First Army. The French and American divisions that were to be under XV Corps control moved to the southern flank of Third Army and fought their way to the Moselle at Epinal and south of it. General Patton noted in his papers on 16 September:

I sent XV Corps against Epinal yesterday. On a corpse we found an order to attack Eddy [XII Corps] in the flank today. They won't do it now...

XV Corps crossed near Epinal and prepared to continue generally northeastward as Third Army's southern wing.

He noted in his diary on 18 September:

We got a message that two columns of infantry and tanks were attacking Luneville.... I told XV Corps to move out on its objective.

Luneville was on the northeastern edge of a great bend in the upper Moselle. XV Corps contributed to quelling the German counterattack that was intended to move on Nancy from Luneville as a base. Twice XV Corps had been in position to frustrate the enemy's main expectation of stopping the Third Army. But he persisted.

On 21 September Patton wrote:

For the last three days we have had as bitter and protracted fighting as I have ever encountered. . . . The Huns are desperate and are attacking at half a dozen places....

The enemy was trying by counterattacks to reestablish firm connection between the German First and Fifth Panzer Armies in the Nancy area. He pressed hardest at one stage against the twelve-mile front of the 35th Division in XII Corps, which on 30 September was overextended after four days of seesaw combat. Perhaps through German SIGINT, enemy artillery was led that afternoon to drop a shell just outside the command post of the 320th Infantry at Bioncourt, where the XII Corps commander, the Third Army Chief of Staff, two division commanders, and three regimental commanders had begun a conference on the situation. Should the line be shortened or should the armored reserve be used? Several men were killed or wounded by the shell, including aides who had begun serving with General Eddy during the campaign in North Africa. After doing what they could to bring relief to the wounded, the XII Corps conferees agreed to pull the 35th Division back to shorter lines.

General Patton flew up from his headquarters at Verdun to Nancy in forty-five minutes and reversed the decision; instead, he committed elements of the 6th Armored Division available to XII Corps and arranged for release of another infantry regiment from XX Corps if necessary. The attack next morning found the enemy even worse off than the Americans; the German counterattack against the 35th Division was thrown back from ground previously taken. By noon the 6th Armored Division held Chateau Salins; the 35th Division held the Foret de Gemecy. On 15 November the 3255th Signal Service Company (RI) moved into Chateau Salins.

Crossing the Moselle began with sharp battles, either on the western side where the terrain was favorable or at the river itself, where high ground on the east bank dominated the crossing site. XII Corps crossed both north and south of Nancy and sent armored forces to envelop a considerable area east of it. Enemy forces within the hilly, often forested, area of envelopment were reinforced. German counterattacks continued for many days, even after Nancy itself had been vacated, so that possession of the crossings was insecure for a period much longer than might have been foreseen.

Near Metz, XX Corps had to overcome strongly fortified positions in areas outlying the city on all sides. It also had to cope with mobile and armored defenders, so that even after gaining and enlarging a bridgehead, it was found necessary to meet repeated German counterattacks. Wooded heights and forested areas interspersed by rolling farm land on clay soil provided opportunities for limited maneuver. The rains that autumn were so heavy and prolonged that rivers flooded their banks. The defense of the city of Metz persisted until surrender of the city on 22 November 1944. Isolated outlying forts remained in the possession of their garrisons until, one after another, they decided to quit. The last surrender came on 13 December.

Before the invasion of Normandy, the German system of assigning callsigns was known. It had been learned partly from a captured callsign book and partly from reconstruction based on traffic analysis. Identifications of terminals were then easy and dependable.

The medium-grade cryptosystems in 1943–44 were either non-Indicator or Playfair, while low-grade systems were usually three-letter (T/L) using the HeeresSignalTafel (HST) as either a one-part or two-part code. Abundant experience with such systems in the Mediterranean had been turned to account in the training of ETOUSA SIGINT analysts. Some enemy divisions, like the 21st Panzer Division, introduced complicating features in the use of T/L codes. That command inserted for all place-names a frequently changing monoalpha-betic substitution system.

As German defense of the approaches to the Rhineland stiffened in September, the reorganization and rehabilitation of German Army units brought with it the resort to new methods of insuring security of their communications. The Allies learned well in advance that on 1 November 1944, callsigns would no longer be assigned by older systems. In fact, they then became randomized. The use of German "E" and "F" callsign books continued, but much less systematically. The new variations, however, tended to become habitual with different units, which could thus be identified. Examples were the 10th SS Panzer Division, 130th Panzer Lehr Division, and the 3d Panzer Grenadier Division.

In February 1945, before the Rhine had been crossed by Allied forces, the German communicators began replacing their non-Indicator cryptosystems with a much more secure "Rasterschluessel." Presumably as control documents could be provided, the new system displaced Playfair systems and thus materially altered the work of reading medium-grade traffic. Captured "Raster" grilles were occasionally available for use in decipherment.

German communications nets had to be identified after 1 November 1944 by scattered bits of typical procedure, references in plain language to known persons or places, types of code used, negligent resort to fixed callsigns, patterns discovered (over a period) in the use of frequencies, and by decrypts. Traffic intelligence of that description required much more recording and detailed analysis of data than had been necessary before the randomizing of callsigns. During operations of such fluidity as the pursuit across France and the ebb and flow of forces in the Ardennes, it became necessary to collect and analyze data not only on units being faced but also on others likely to be in opposition because of sudden moves. Wanted were maps, means of understanding references in traffic to German map grids, and data gathered by other corps or armies. That caused Third Army's SIS to establish a research section to act in liaison with counterparts at corps, other armies, and army group levels.

When the boundaries of Allied army zones or corps areas were shifted, a corps signal service company (RI) was likely to begin covering an enemy command that, while new to it, had previously been covered by another U.S. RI company. From army or army group SIGINT units, the needed collateral could thereupon be sought and quickly applied.

In August 1944 the movements of the 9th Panzer Division were followed by U.S. SIGINT units because the non-Indicator cipher keys used by that command had been captured. Other captured documents expedited the processing of intercepted traffic, especially when code names for persons, units, and even some types of war material were copied for the first time. When enemy communicators changed frequencies every three days, captured tables of frequency allocations proved highly useful to the SIGINT analysts. Captured prisoners from time to time helped to identify the most useful frequencies and links.

The communications changes adopted after 1 November 1944 by the German Army on the Western Front produced so much difficulty for U.S. tactical radio intelligence units that, first at the SHAEF level and then on 10 December 1944 at 12th Army Group, conferences of SIGINT representatives sought to pool their experiences. Attending the SSD "D" conference were representatives from G-2, 12th Army Group; SSD "D"; the Signal Intelligence Services of First, Third, and Ninth U.S. Armies; each SRI company, and each signal service company (RI). The conferees on 10 December 1944 agreed to use various methods developed among the units for meeting certain problems. These included methods of approach in traffic analysis, of exchanging results of T/A, and of reporting continuities discovered in the enemy's allocation of frequency groups. Captured signal documents were to be speedily reported and disseminated. Ways of controlling DF securely by radio – since wire lines had been found vulnerable to enemy artillery and even to friendly agents – were adopted. An acceptable approach to VHF intercept was tentatively reached, while the methods being used on three-letter codes were judged worth continuing. In view of the enemy's changes, and because SID, ETOUSA, had an advance detachment operating on the continent, the routing and processing of raw intercept was modified. Only non-Indicator traffic was to be considered medium-grade henceforth. Decoded medium-grade material would in the future be sent to First, Third, and Ninth Army SIS officers instead of G-2, ETOUSA.

Early in October 1944, while Third Army was gathering strength and awaiting the signal to resume the offensive, the 3256th Signal Service Company (RI) heard an unidentified artillery net for the first time. It was given a serial number and passed a series of "routine" reports from 15 to 23 October that were associated with that number. The reports mentioned personalities, gave mileages covered, fuel consumed each day – nothing that seemed striking. But on 24 October all that changed. First the net transmitted a series of coordinates. Then it exchanged visibility reports. About two hours later, at 0040 hours, came the following: Ready. First shot. Time and percussion fuze. . . . Then a long dash. About thirty seconds later the first round of a monster 280-mm shell could be heard passing overhead. It landed near the XX Corps CP in Conflans-Jarny. The mystery was solved.[139]

The huge railroad gun became as famous as "Anzio Annie" had become. Radio surveillance enabled the SIGINT unit to give a report of almost every firing and to warn when the gun was being loaded. XX Corps artillery, alerted by direct wire, could correlate its sound-flash data. Direction finding on the enemy observers' reports, and a study of the coordinates, helped locate the gun. Its target became predictable – whether Conflans-Jarny, Nancy, Pont-a-Mousson, or elsewhere within its great range. The two-hour interval to load and aim provided time to take suitable protective measures. It had not yet been destroyed when the enemy resorted to his new, randomized callsign allocations and began using "Rasterschluessel." The last intercepted traffic from the enemy net came on 20 November 1944.

It was not the only such gun employed by the enemy but the first in Northern Europe in World War II. Another hit near Headquarters, SSD "D," in Luxembourg City on 28 October. The veterans of World War I could remember "Big Bertha," the weapon that struck Paris, including a church filled with people at prayer.

The invasion of southern France, Operation DRAGOON, succeeded so well during the first two days of landings that the enemy appeared to be pulling back. From special intelligence, the Allies learned that German ground troops were abandoning southern and southwestern France and were returning to defend the Fatherland. The Ninth Air Force's Signal Intelligence Service soon detected so much radio traffic at airdromes near Bordeaux, Dijon, and Bourges that they concluded the Germans were evacuating their upper-grade officers by air from those places. In three days' time, successive Allied air sweeps found it possible to destroy thirty German transport aircraft.[140]

General Patch had to decide whether to push steadily after the enemy's rear units or to attempt to outflank his main body and try to cut off the retreat. If he tried the latter maneuver, he risked an attack on his own right flank from enemy forces in the Maritime Alps. His own line of communications to the beaches might thus be cut.

From SIGINT there was no indication of anything but a defensive attitude on his flank. The Seventh Army's unloading plans were modified to rush vehicles and fuel ashore in order to reinforce the pursuing "Task Force Butler" by sending the 36th Division deep in the enemy's rear.

Knowing from SIGINT that the enemy was unaware of the character of the U.S. forces there, and that he believed that only guerrilla forces were gnawing at German lines of communication, Seventh Army withheld from the war correspondents any information about "Task Force Butler" – its existence or its operation.[141]

At Montelimar Seventh Army established a strong road block across the German XIX Army's route of escape. Only by abandoning their heavy equipment could the Germans extricate personnel from the trap after a hard and costly battle.

The U.S. Seventh Army moved into the front south of Third Army, sealing off the area east of Be-sancon as far as the Franco-Swiss border. Under 6th Army Group (Devers), both U. S. Seventh Army and French First Army prepared to push into Alsace and southern Germany. Effective 29 September 1944, XV Corps was transferred from Third to Seventh Army, from 12th to 6th Army Group. In part, that action was based on the fact that Seventh Army was being well supplied through Marseilles instead of being short of men and ammunition like Third Army, which was supplied from Normandy. The transfer of XV Corps seemed to make a renewed offensive by Third Army less likely to succeed in seizing Sarreguemines.

On 2 November 1944 Third Army was authorized to resume its offensive of about sixty miles across Lorraine to the Westwall, starting a week later, at a time when the U.S. First and Ninth Armies would be attacking, too. When the ten-division attack opened on 8 November, with fire from more than 400 guns, the data gleaned by special intelligence and other sources enabled the shelling and supporting air (later in the day) to strike at all known enemy command posts. Enemy radio soon confirmed that the enemy's loss of control before the ground attack began had been drastic. The weather cleared enough in mid-morning to let the supporting planes see the targets and work ahead of the advancing ground troops. For the next few weeks it rained almost every day, and often all day and night. There were many streams between the Moselle valley and the Saar basin-the Meurthe, the Seille, the Nied, and the Saar Rivers – so that any repetition of the far-ranging armored columns of the previous August were rendered wholly impossible. The Saar River, normally about fifty feet wide, was swollen to 300. Tributaries backed up and overflowed their banks. As at Anzio a year earlier, even tracked vehicles struggled with the mud, and heavy ones, like the tanks, were held to the roads.

XX Corps and XII Corps slugged their way nonetheless to the edge of the Westwall and by 14 December had begun to penetrate it. Discouragement then became widespread. All things considered, Third Army was probably not strong enough for the mission. Although its commander was able to drive about in Saarlautern on the 14th, that city was not behind the fortified zone but within it. A few days later, on 20 December, Third Army was being drawn away to the Ardennes sector, about 100 miles to the north.

To reinforce the Germans facing the Third and Seventh Armies, the veteran 3d Panzer Grenadier Division, in almost full strength, was shifted from the Italian front. It became for Third Army the principal source of low-grade traffic conveying tactical intelligence. Three other divisions shared that function: the 116th Panzer Division, the 2d SS Panzer Division, and the 15th Panzer Grenadier Division. The 1st Panzer Artillery Corps supplemented the intercepted material from these four divisions. When Third Army was attacking near Nancy and Metz, reconnaissance units of the 3rd Panzer Grenadier Division not only reported their observations of American movements but also gave away the identities and locations of opposing German units.

Some SIGINT indicated that in November three German divisions were pulling out of the line facing Third Army. They were the 130th Panzer Lehr, 11th Panzer, and 21st Panzer Divisions. When the Third Army turned north in December to take command of operations along the south limits of the German salient in the Ardennes, they soon picked up reports there by the 130th Panzer Lehr Division's reconnaissance units. The 116th Panzer Division, another familiar enemy unit, also turned out to be west of Bastogne. A great battle lay ahead.

[138] Harry R. Turkel, Lieutenant Colonel (Res), The Signal Intelligence Service of the Ninth Air Force in World War II, written by the former Chief, SIS, Ninth Air Force from memory in 1951. NSA Hist. Coll.

[139] SGCO-3256.0.1, 3256th SS Co (RI) Opnl and Intell Hist for Period 5 May 1944 to 31 May 1945. Box 23223, WNRC.

[140] Turkel, The Signal Intelligence Service.

[141] Synthesis of Experiences in the Use of Ultra Intelligence by U.S. Army Field Commanders in the European Theater of Operations. USA SSG, History Files (Book No. 53), 26.