The German strategy of resolutely defending successive belts of prepared positions across Italy south of Rome enabled the enemy to absorb Allied offensive power while inflicting heavy losses. It used up Allied resources that might have been used elsewhere, perhaps more injuriously. The same could be said, however, about the German divisions that remained in Italy instead of providing in France the defense in depth that might have turned the scale in the invasion of Normandy. The concept of the defensive line sustained the mistaken notion that battles were for territory rather than for the destruction of hostile firepower. On Hitler's specific orders, place after place was held "at all costs"; the resulting action became more brittle than elastic. Once the Gustav-Hitler Line was pierced anywhere by strong forces, the whole line was threatened, and the formations had to pull back to, or through, the next line south of Rome. No matter how well executed, the retreat and rear-guard actions were inevitably costly.

Four of the German divisions emerged from the Allied offensive below Rome as mere shells. Seven others were drastically depleted. On 5 June 1944 both the German Tenth and Fourteenth Armies were weak and in retreat. A persistent, ruthless Allied pursuit could then have harried them swiftly to the outposts of the incomplete "Gothic Line" across Italy, north of the Arno River and through the Apennines to the Adriatic near Pesaro. Allied pursuit was neither strong nor quick, while the opportunity was most promising, but German reinforcements, including four new divisions, were speedily moved to northern Italy from the Balkans, Denmark, Holland, and Germany. Fourteenth Army received a new commander, General Joachim Lemuelson, on 6 June, in place of General von Mackensen. Kesselring intended to delay the Allied advance at every advantageous intermediate position so that the Allies would, at best, reach a belt of defenses north of the Arno too late to break through the Po Valley before winter.

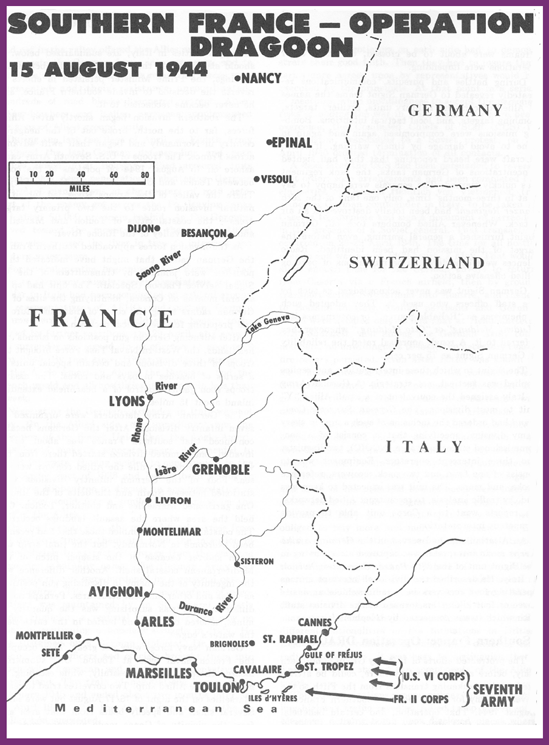

For a few weeks it remained uncertain whether Alexander's 15 Army Group would be allowed to remain at full strength until its adversaries in Italy had surrendered. An alternative claim upon some of the resources at his disposal would be an Allied amphibious invasion in southern France. That operation had been included among understandings between the Allies and Stalin; it had been a goal of the militant French at least since 1942 and perhaps since 1940. As a method of facilitating the success of Operation OVERLORD, the earliest possible invasion of southern France would be more than two months too late. As a contribution to Allied success in overcoming Germany, it might be argued that pushing all German forces from southern France into northern Europe would not accomplish anything more valuable than would defeating completely all German forces that could be drawn into northern Italy. Advocates of a campaign in southern France, to include the capture of Marseilles, finally prevailed at about the same time that the Germans were able to arrest the Allied pursuit north of Rome. The U.S. Seventh Army, commanded by General Alexander Patch, would land in southern France – Operation DRAGOON.

Transfers from the U.S. Fifth Army to the U.S. Seventh Army, for participation in Operation DRAGOON, took away from 15 Army Group the U.S. VI Corps of three divisions, the French Corps of four divisions, plus many nondivisional American units. In Italy IV Corps took over from VI Corps on 11 June 1944. The French left a month later. Many of General Alexander's supporting air formations were switched to support of Seventh Army. Thus, at the same time that Kesselring's Army Group C was being replenished, the Allied force opposing him was reduced. After Hitler learned of the Allied reorganization, and in the face of crumbling German defense on both Eastern and Western Fronts, he withheld some of the reinforcing divisions promised to Kesselring. Eventually both the U.S. Fifth Army and British Eighth Army were strengthened in time for the final push to the floor of the Po Valley.

At first the Allied pursuit in June 1944 was led by the French Corps. After the French were withdrawn to embark for their return to France, Fifth Army moved up to the Arno River, with U.S. IV Corps along the west coast, U.S. II Corps further east, and, British Corps on the eastern wing. Ancona and Leghorn were captured on 18/19 July as valuable ports to support the renewed Allied drive. British Eighth Army successfully masked the swift shifting of the bulk of its strength to the Adriatic sector. Instead of making the main effort directly north of Florence through the Futa Pass and along the Florence-Bologna highway No. 65), 15 Army Group struck along the Adriatic coast. Eighth Army broke through the Gothic Line, took Rimini on 4 September but stopped short of Ravenna. After Kesselring had moved troops eastward from the center of his line, in order to hold the Eighth Army, the Fifth Army on 10 September-began its attack; it started as the pursuit of a withdrawing enemy. On 13 September, however, the Americans reached the main German defenses and fought a hard battle. Near Firenzuola, II Corps found a way to outflank a key pass on Highway 65 and thus to start working down through the northern mountains toward Bologna at their base. On 27 October, when Kesselring rushed troops to check that attack short of Bologna, Eighth Army resumed its advance. On 4 December it finally captured Ravenna, but it had reached an area of streams, marshes and lakes fed by the rains and snows of winter, where the roads were often causeways. The terrain was reminiscent of the Anzio beachhead in those respects.

Italian Fascist forces fighting for Mussolini's government on the side of the Germans tried in the Senio Valley during Christmas week to duplicate the contemporaneous Ardennes offensive, on a smaller scale. It was a feeble effort.

From January through March 1945, stalemate along a static front prevailed among the ground troops. On both sides, important changes in command occurred. Kesselring went to Germany to direct the final defense. Vietinghoff moved up to become Oberbefehlshaber Sudouest, commanding Army Group C. Lieutenant General Traugott succeeded him in command of German Tenth Army. From AFHQ at Caserta, Field Marshal Sir Henry Maitland Wilson went to Washington to take up the mission there of the late Field Marshal Sir John Dill in the Combined Chiefs of Staff. General Alexander succeeded him as Supreme Allied Commander, Mediterranean Theater, and General Clark left U.S. Fifth Army to succeed Alexander as commanding general, 15 Army Group. General Oliver Leese turned over British Eighth Army to Lieutenant General R. C. McCreery in order to move to Burma. To command the Fifth Army, Lieutenant General Lucian Truscott was brought back from U.S. VI Corps, then in France.

The I Canadian Corps and its two divisions left Eighth Army for western Europe to join the First Canadian Army in the 21st Army Group. Fifth Army gained the new U.S. 92d Division and the specially trained U.S. 10th Mountain Division.

The renewed Allied drive through German defenses shielding the Po Valley opened on 2 April 1945 with diversionary operations on the two coastal wings. A week later, preceded by an extremely heavy artillery and air bombardment, the Eighth Army headed for Ferrara and Bologna. On 14 April Fifth Army attacked on a relatively narrow front along mountain streams and over adjacent heights, to approach Bologna from the south and southwest. In turn, each army shared the benefits of Allied air supremacy in support of its offensive. By nightfall on 20 April both Fifth and Eighth Armies had come to the valley floor, where mobility and armor could begin to play decisive roles.

The enemy had not been permitted by the highest command to develop strong defenses along the northern bank of the Po River and in the foothills of the Italian Alps. Since Allied bombers had destroyed all bridges across the Po, the enemy had to lay pontoons, to use boats and ferries, and after crossing, to develop defenses hastily that might have been better built if done during the previous winter. To reach the river he had to cross terrain that furnished little shelter from air observation and harassment. He was already short of fuel. Heavy vehicles and weapons had to be abandoned on the south bank. Moreover, the extensive road net in the valley offered the Allies an opportunity to separate the German forces into segments, and to cut them up further until their remaining forces were fragmented and their resistance uncoordinated. Hundreds of road blocks hampered retreat. Allied fighter-bombers and Italian partisans supplemented the guns of Allied ground units.

During the last ten days of April, as Eighth Army unhinged the last German defense line and both armies closed in at Bologna, Allied armored units began their deep penetrations, shattering German control of many towns at the centers of road nets. Part of the enemy got across the Po, leaving tanks and about 50,000 prisoners behind. As the Germans moved toward the mountains in the north, Allied forces also crossed the river in time to intercept and capture many more.

For several months, beginning before Kessel-ring had gone to Germany, highly secret negotiations for surrender in Italy had been conducted on neutral ground by representatives of AFHQ and certain German commanders in Italy who could see no benefit to be gained by further sacrifices. On 29 April, at Caserta, the surrender was signed, to be effective at noon on 2 May 1945. By that time, Hitler was dead; surrender to the Anglo-American Allies, the Russians, and the French would end all hostilities in Europe in less than a week.

Negotiating the German surrender in Italy was not easy. On the Allied side, one impediment was the suspicion of the Soviet Union that the Anglo-Americans would make a separate peace detrimental to Soviet interests. Having yielded to opportunism in the Nazi-Soviet Pact of 1938 and having been willing to meet von Ribbentrop to discuss an accommodation in 1943, they could fear a similar opportunism on the part of the Allies.

On the German side, the main difficulty arose from the divisions among them and from the intention of some officials to extract advantage from the way the cease-fire eventually came. The German Army and Luftwaffe officers were burdened by a personal oath to Der Fuehrer. The initiative and momentum of negotiations was maintained by an SS general directly under Himmler, a regional commander who saw no point in continuing a hopeless struggle in Italy. He was sustained by a German diplomat, Dr. Rudolph Rahn. Lesser officers and officials brought them into touch with American and British representatives in Switzerland. The train of negotiations began on 25 February 1945 and ended about two months later, on 29 April 1945, after the Allied offensive into the Po Valley had succeeded.

First, the negotiators on each side had to demonstrate their good faith. Then they had to insure that terms once agreed upon by representatives would be executed by the principals. At that point in a series of meetings, when unwillingness to accept the personal risks of ending the war in Italy seemed to have been overcome, the Combined Chiefs of Staff (CCS) in Washington, responding to a Soviet protest, on 20 April 1945 ordered termination of all contacts.

A week later the CCS had been persuaded to reverse that order; soon arrangements had been completed for emissaries of General Heinrich von Vietinghoff, the principal German commander in Italy, to be taken to Caserta to complete and sign a document of surrender in the presence of a Soviet general. That transaction occurred on 28–29 April 1945. The time for all hostilities to end was set at 1400 hours, 2 May. That would allow enough time for the German envoys to return from Caserta via a French airfield, then by ground transport across Switzerland into Austria, and thence to Bolzano in Italy. Italian partisans and German police were avoided only to find that at Headquarters, O.B. Sudouest, and among the German Army commanders, an unwillingness to issue the necessary ceasefire orders persisted. Even after Hitler was known to have killed himself and the end had come for Nazi Germany, turmoil in Italy persisted. The orders did go out in time, but the instrument of surrender was not officially validated until later that afternoon.

On 4 May 1945 German and Allied staff officers began spelling out the processes of pacification. Two days later, in southwestern Germany Army Group G, facing General Devers' 6th Army Group, surrendered.

After the surrender in Italy, General von Vietinghoff and some of his principal subordinates were interrogated about the role of SIGINT in their experience of command. They pointed out that they had been obliged to rely more and more on it because of the drying up of their other sources of intelligence. SIGINT provided data on activities in rear areas from which they might judge what the nature of future Allied operations would be SIGINT became the chief means of learning about reinforcements or reliefs by fresh Allied divisions. The communicators of Allied divisions had characteristic transmission traits. In view of the many different nationalities of the formations in British Eighth Army, reflected in languages, dialects, and to radio transmitters, it was easy to distinguish them. Traffic analysis showed the components of the Allied corps.

The communications among military police controlling highway traffic revealed Allied troop movements. Messages defining bomb lines disclosed places where streams were about to be crossed, or where other operations were impending.

During battles and pursuits, communications repeatedly revealed to German SIGINT teams the names of Allied officers and military units, artillery targets, bombing targets, and local tactical intentions. Bombing missions were compromised again and again in time to avoid damage by timely warning. If Allied aircraft were heard reporting that they had sighted concentrations of German tanks, the tank regiment was quickly warned. The generals were happy to say that in three-months' time, only one tank of the 26th Panzer Regiment had been totally destroyed in an air attack. Whenever Allied bombers took off, German SIGINT furnished a general warning even before the target of the mission had been identified. Radio silences were considered to be indications of pending Allied offensive action.

German SIGINT was never acknowledged as such by the staff officers who used it. They adopted such euphemisms as "Reliable Source," or cover-names like "Ludwig Meldung" or "Otto Meldung," whenever they referred to it. A rough appraisal rated the reliability of German SIGINT as 75 percent.

The SIGINT to which these interrogations and replies applied was tactical, not strategic. A German Army in Italy assigned the equivalent of a small Allied "Y" unit to most divisions. The German Supreme Command had ordered the inclusion of such a unit in every Army division, specifying that it consist of a noncommissioned officer in charge (NCOIC), two linguists, and three intercept operators. Equipment was to consist of one fixed and two pack receivers, reference books, and maps. The unit was expected to keep logs and, by traffic analysis, to reconstruct Allied networks. Its reports went to a corps unit able to provide competent interpretation.

An Alsatian who had served in the German Afrika Korps as an interpreter was captured after serving in the SIGINT unit of the 29th Panzer Grenadier Division in Italy. He described the divisional intercept unit as operating four receivers in a radio vehicle at a site three or four kilometers forward of the division staff, with which it was connected by telephone.[85]

The protracted efforts of 15 Army Group in northern Italy, before achieving victory there, could be attributed to the weakening transfers from the Fifth to the Seventh Army for the invasion of southern France in August 1944. That operation, and certain beneficial consequences that offset the arrested development of the opportunities in Italy, are summarized below. It should also be noted that until a few days before the landings, the prime minister persisted in efforts to reverse the decision to invade southern France, and he never became reconciled to it.

The southern invasion began shortly after Allied forces, far to the north, broke out of the hedgerow country in Normandy and began their swift advance across France. The troops of the U.S. Seventh Army came ashore on 15 August 1944 on portions of the coast between Toulon and Cannes, near the Gulf of Frejus. There the valley of the Argens River led inland, a natural invasion route to the two primary target areas – the coastal cities of Toulon and Marseilles and the inland valley of the Rhone River.

As the invasion forces approached southern France, the German radars that might have indicated their positions were jammed by transmitters of the 1st Signal Service Platoon (Special). The unit had spent several months on Corsica, identifying the sites of all German radars along the coast of mainland Europe and preparing for the critical occasion.[86]

After silencing German gun positions on islands and headlands, the Western Naval Task Force brought the troops of three divisions and certain special units to a series of beaches in bays and coves. The assault troops soon gained control of a beachhead extending inland about fifteen miles.

The German Army defenders were organized as seven infantry divisions. After the Germans became convinced that southern France was about to be invaded, one armored division started there from the vicinity of Bordeaux while the Allied convoys were at sea. Four of the German infantry divisions were stationed between Spain and the delta of the Rhone. One garrisoned Marseilles and another, Toulon. One held the area where the assault landings occurred. The coastal defenses resembled those that had recently been overcome in Normandy, but the tidal strip was much shorter because of the steeper pitch of the Mediterranean coastal shelf. Another difference was the ingenuity of the enemy in disguising gun positions as villas and other innocent structures. Perhaps not so different as it was surprising was the quantity of mines, moored offshore and buried in the earth near the water's edge.

German Navy forces were not great. They occupied the French naval base at Toulon. One submarine moored there tried unsuccessfully, while escaping, to attack a large Allied ship. Two corvettes tried to reach Marseilles on the night of 16/17 August but were sunk. Several small and speedy boats from that area and from the vicinity of Genoa made nuisance raids but accomplished little. From an old French battleship, perhaps one scuttled when the Germans moved into unoccupied France in Novem-ber 1942, a turret of great 340-mm guns had been transferred to a cape south of Toulon and installed in a casemated position. It was adjacent to elaborate underground facilities for its crew and ammunition, and for defenders manning other guns emplaced nearby.

The German Air Force, greatly reduced and endlessly harried by Allied air formations, could assemble strength enough for a few attacks, generally at dusk. But for two previous weeks, Allied planes had struck several coastal areas, masking their actual choice of one for the assault, while damaging and destroying enemy defenses in them all. The results of such repeated bombings were supplemented by a final strike at the beachhead just before the landing craft approached on 15 August 1944. Perhaps 30,000 enemy troops were near the assault areas, and they were dazed and dispirited. The much larger number that might have been sent in as reinforcements could not be moved over destroyed bridges and disrupted roads or railroads with sufficient speed to equal the rate of Allied buildup. Allied air support from escort carriers and Corsican airfields was supplemented by new airstrips in the beachhead area.

Operation DRAGOON was a triumph attributable to the application of experience during planning, organization, training, and execution. Participants in earlier amphibious assaults were to be found at all levels, from commanders to GIs and able seamen. Vice Admiral Henry Kent Hewitt, USN, had been a naval task force commander in TORCH, HUSKY, and AVALANCHE. Lieutenant General Alexander Patch had commanded in the Pacific. Major General L. K. Truscott, Jr., had accompanied the Dieppe Raid by British Commandos and since then had had commands in TORCH, HUSKY, AVALANCHE, and SHINGLE. The 3d, 36th and 45th Divisions had each been in one or more such assaults, and were veterans of tough battles ashore. Training under conditions resembling those in southern France had taken place in the Naples area. Moreover, after certain preliminary diversions and deceptions before daylight, the assault landings began in daylight. H-hour was 0800 hours. And unlike earlier Mediterranean operations of the same type, they were preceded by heavy naval bombardment, as well as by air bombing. The success was no accident. Even an airborne force was dropped, for the most part, where it was needed.

On a misty morning, the troops approached the beaches through mine-swept lanes to find their inland objectives covered with clouds of dust and smoke. The left wing of VI Corps was the 3d Infantry Division, commanded by Major General John W. O'Daniel. Two of its regimental combat teams went ashore on opposite sides of a cape south of St. Tropez. Resistance was weak. Before noon the division CP was ashore. By nightfall, advance elements were about six miles inland. At midnight the inflow, in round figures, amounted to 16,000 men, 2,150 vehicles, and 225 tons of supplies.

In the center of the assault was the 45th Division, commanded by Major General William W. Eagles, which landed smoothly without opposition at points along three miles of sandy beach. Land mines gave some trouble there, but before D-Day had ended, thousands more men and vehicles had landed. The troops overcame opposition at villages inland, and cleared the way for the division commander in the morning and the VI Corps commander in the afternoon to establish headquarters ashore.

The 36th Division, under command of Major General John F. Dahlquist, came in nearest to the Gulf of Frejus as the right wing. St. Raphael, on the northern shore of the Gulf, was a major objective. Despite the preparation fire and bombing, the invaders met considerable opposition. The plan called for eliminating enemy gun positions that covered the Gulf so that the waters could then be swept free of mines, after which assault troops would land during the afternoon of D-Day. The schedule could not be met. The earlier landings were accomplished in part by switching one regimental combat team (RCT) to a portion of the beach being used by a second RCT and in part, aided by naval gunfire, by clearing the enemy from headlands and high ground along the coast. The available beaches served for landing some 30,000 men and 5,000 vehicles during the first three days, but only then could the sheltered beach at the head of the Gulf of Frejas be used.

Late on D+1, General Patch was satisfied that the beachhead was firmly held. The French II corps under General De Lattre de Tassigny was then coming ashore despite an enemy air attack. Another French Corps would soon arrive. Patch's Head-quarters, Seventh Army, left the USS Catoctin to occupy a villa near St. Tropez.

During the next two weeks the invaders gained control of the French coast from the border of Spain to that of Italy. Cannes and Nice were occupied by 30 August. A 1st Airborne Task Force in the hills and along the Var River, and a screening naval force offshore, protected the beachhead from possible depradations originating in northern Italy. On the western flank, French forces ashore and Allied naval units cleared the enemy from small ports and protecting islands. But the main objectives of the invasion were to gain two great ports – Toulon and Marseilles – and to press the German Nineteenth Army northward up the Rhone Valley, and perhaps destroy it.

In planning tactics, General Patch was able to disregard the risk of an enemy attack along an extended flank because from Special Intelligence, he knew that the Nineteenth Army had been ordered to retreat to the German lines much farther north. About two days after the landings began, Hitler ordered the withdrawal. On 17 August 1944, within five hours of their transmission, the orders conveying the decision had been decrypted and provided to SHAEF. General Patch thereupon sent a blocking force far ahead of the pursuing main body.

The 3d Division alone attacked up the Rhone valley while the 45th Division protected its east flank, and while the 36th Division and an armored task force tried, by a longer route, to block the German retreat at defiles near Montelimar or Livron. The attempted encirclement used a route through Sisteron and Aspres to the Drome River, which could be followed westward to the Rhone. Part of the 36th Division did not turn west but continued over the divide into the Isere River valley as far as Grenoble. Although part of the German forces avoided capture, about 57,000 men did not.

The French, moving westward from the bridgehead, encircled Toulon and began to invest Marseilles, while a naval force sought to open the way into Toulon harbor, past the islands and headlands on which German defenders remained. For about one week their 340-mm battery and some of the other guns defied the shells of Allied ships and the renewed Allied air bombing. On 26 August resistance there ended. Two days later, affected in part by news of the liberation of Paris and in part by the obvious strength of the Allied invading force, the enemy at Toulon and Marseilles surrendered. Remaining pockets of enemy in the coastal area were soon eliminated.

As early as 3 September, use of the port at Marseilles began while the demolitions were being cleared and repairs effected. In case Marseilles had held out longer or had been left unusable for too long a period, the Allies had cleared the mines at another port, Port de Bouc, some twenty miles west of Marseilles, and had opened a canal from that point to the Rhone River at Arles. By 25 September the captured beachhead was no longer needed; un-loadings there had totaled more than 320,000 men, 68,000 vehicles, nearly 500,000 tons of supplies and large amounts of gasoline. (At the end of hostilities in Europe, through the port of Marseilles, supplemented by Toulon and Port de Bouc, 905,000 more men and over four million tons of cargo had moved inland.)

The arrival of French I Corps resulted in establishing a French Army "B," temporarily subordinated to the U.S. Seventh Army but soon superseded by a French First Army which, like U.S. Seventh Army, came under the control of 6th Army Group. The latter, having moved from Bastia, on 15 September 1944 assumed control at Lyon under Supreme Headquarters, Allied Expeditionary Forces. Seventh Army was then already in contact with the U.S. Third Army, first at Sombernon on 11 September, and later at other points. On 21 September, XV Corps shifted from Third to Seventh Army control.

The tactical SIGINT service available to Seventh Army in the course of its invasion of southern France was inconsiderable by comparison with what came later. The VI Corps SIGINT unit consisted of the newly designated 3201st SIS Detach-ment (three officers and eighteen enlisted men) formerly known as Detachment "E," 849th SIS, in combination with Detachment "B," 117th SRI Company (3 officers and 105 enlisted men), and under command of Lieutenant Frederick V. Betts. The intercept operators had been working since March at a station on Corsica covering enemy traffic from southern France. The intelligence personnel had been preparing since June for the shift from Italy to France. They all sailed from Naples divided among three transports of the D+ 5 convoy. Assembling at St. Tropez, they moved 180 miles inland on 24 August to Asp res. A week later they were in Charnacles, and by 9 September were in the vicinity of Besancon when VI Corps, with all of Seventh Army, came under control of SHAEF.

The SIGINT unit at General Patch"s Head-quarters, Seventh Army, consisted of five officers and twenty-six enlisted men. Detachment "B," 849th SIS, was combined with Detachment "A," 117th SRI Company (3 officers and about 143 enlisted men), and commanded by Captain Edward J. Heinen. The unit moved from Corsica, where it had been training with Lieutenant Bett's detachment, to St. Tropez on the night of 30/31 August 1944. Three days later it moved almost 240 miles to the vicinity of Grenoble; by 20 September it was at Ve-soul.

Relatively little use was made of tactical SIGINT during the landings and inland advance of Seventh Army, because of the fluid nature of the rapid advance, as the enemy withdrew. More important to Seventh Army's pursuit was the monitoring of communications among its own forward units.

The 3151st Staff Information and Monitoring Company (SIAM), commanded by Captain Reinardo R. Perez, was an instrument for control by Seventh Army G-3 rather than for producing signal intelligence information for G-2. Fifth Army had had such a provisional unit from which it transferred all but a cadre to form the 3151st SIAM. After activation at Cecina, Italy, on 18 July 1944, the new unit assembled the personnel needed for its platoons. Besides a headquarters platoon, it consisted of platoons for each of two corps (U.S. VI and French II) and four divisions, supplemented by several liaison officers. Actual strength was 14 officers and 225 enlisted men.[87]

The platoons monitored all radio nets within Seventh Army for adherence to radio and cryptographic security instructions, but their main function became that of conveying to commanders the substance of messages passed at lower echelons that showed American positions, situations, and intentions. Instead of relying on periodic reports and other messages specifically intended to keep higher headquarters informed, the commanders benefited from what amounted to SIGINT about their own units. And from the SIAM company's own radio nets the platoons copied, for their commanders, all tactical messages of consequence; the system was thus a means of prompt lateral as well as vertical movement of information. When enemy SIGINT was heard, it was, of course, passed to G-2 via its SIGINT Section. During a pursuit like that by Seventh Army from southern France to Alsace, the SIAM company served its purpose so well as to draw observers from Third Army and 12th Army Group to see how that was accomplished.

One of the liaison detachments of the 3151st SIAM Company first reported that Seventh Army and Third Army reconnaissance units, the first from southern France and the other from Normandy, had made contact near Sombernon on 11 September 1944.

When XV Corps was transferred from Third Army to Seventh Army, it obtained a new SIAM liaison team on 29 September.[88]

After AFHQ had mounted Operation DRAGOON, the U.S. Seventh Army moved under SHAEF operational control and a little later under the administrative and logistical services of the European Theater of Operations, U.S. Army. As we have noted earlier in this history, the Mediterranean Theater shrank within a boundary that ceased to include southern France. The route through Marseilles and Toulon became that over which a tremendous volume of reinforcements and supplies reached the fighting front in eastern France and in Germany.

The Mediterranean became the secondary theater, as the Americans at least had expected. The cross-Channel invasion and the campaign in western Europe was executed by much larger forces using means and methods tested in the Mediter-ran-ean. Those campaigns were a culmination of Allied experience.

By 7 September 1945 two increments of the 849th SIS had already returned to Fort Monmouth, N.J., from the Mediterranean Theater of Operations. One had been allocated to reinforcing the 2d Signal Service Battalion; the other was scheduled to augment the 3126th Signal Service Company (RI) for duty in the Pacific – events there made such deployment unnecessary. Both groups remained in the 849th SIS until its deactivation later that year.

[85] AFHQ Interrogation Report, Microfilm Reel 98–1; AFHQ Intell Notes, No. 68, No.1 02, on Reel 26A.

[86] The unit had previously prepared for operations to retake Kiska Island in the Aleutians, and after that episode moved to the Mediterranean. From Corsica it returned to the U.S. for redeployment to the Central Pacific. History of the SSA in WW II, Vol. X, 62–3.

[87] Fifth Army organized the 3326th SIAM Company around a cadre from its provisional unit in September 1944.

[88] Historical Record Report, 3151st SIAM Co., 20 Aug 1944.