“The time has come, ‘the walrus said,’ to talk of many things. Of shoes and ships and sealing wax, of cabbages and kings…”

Chapter Five

An Invitation to the United States

I was happy with what I was doing at ICI, and I had had no thought of academia. But in the course of solving practical problems, I had come up with a number of ideas for the development of statistical methods and had published them. In 1952, I was surprised to receive a letter from North Carolina State University at Raleigh, which had established one of the first departments of statistics in the United States.1 The letter was from Miss Gertrude Cox, who famously ran the Institute of Statistics with departments on both the Raleigh and Chapel Hill campuses. It was an invitation to spend a year at Raleigh as a “Visiting Research Professor.”

I later found out how this came about. J. Stuart Hunter, then a graduate student at Raleigh, had worked during the summer vacation at the Army Research Office (ARO) (Figure 5.1). Stu had seen the paper I had written at ICI with K. B. Wilson in 1951, which concerned the experimental determination of optimal process conditions. He showed this to Frank Grubbs, who was in charge of ARO, and Frank proposed to Gertrude that she use some ARO funds to invite me over. The ICI board of directors gave me a year's leave of absence, but they made it clear that they wanted me back.

Figure 5.1 George Box, Ralph Hader, and Stu Hunter.

At that time, I had not submitted my Ph.D. thesis. People told me that, although this didn't matter much in England, in the United States, everyone was supposed to have a Ph.D. I had already written my thesis, much of which had appeared in already published papers. So I had my examination just a few days before I was to leave for the United States on the Queen Mary. My examiners, E. S. Pearson, H. O. Hartley, and M. S. Bartlett didn't mention statistics but chatted with me about the comparative advantages of going to America by air or by sea. When I asked if I'd passed, they said, “Yes, of course.”

At ICI I was attached to a group called the Miscellaneous Chemicals Division. It included various activities such as X-ray Crystallography that didn't fit anywhere else. Our boss was Dr. S. H. Oakeshott. When the board decided I could go to the United States, Oakeshott asked me to come and see him. He said, “Now we'll need to give you some money to get to North Carolina because it's on the west coast of the United States and it's a long train ride.” I told him, “No, it's in the east.” We had a discussion, and finally I remembered the words to the song “The Chattanooga Choo Choo.” I sang some of the words to him:

You reach the Pennsylvania station ‘bout a quarter to four,

You read a magazine and you're in Baltimore

Dinner in a diner

Nothing could be finer

Then to eat your ham and eggs in Carolina

[Citation: Harry Warren and Mack Gordon, 1941; first recorded by Glenn Miller and His Orchestra in 1941.]

I said, “So you see, it's got to be on the east coast.” He was a very nice man of the “old school tie” type, and he didn't seem to follow me, but eventually we got out a map and he realized that I was right.

Jessie and I left Southampton on the Queen Mary in the middle of winter. When we first arrived at the dock, there was great excitement on board with cameras and lights everywhere. It turned out that Sir Winston Churchill was crossing to see President Eisenhower. Two or three members of his family and a number of important people were there to see him off. There was much flashing of cameras and general commotion, but eventually he was ushered away. Jessie and I had been watching all of this from close to the top of the gangway. We too decided to move on, but didn't know our way around the ship. We found ourselves walking down a narrow corridor where we could just see two people walking toward us from the other end. It turned out to be the Captain and Churchill. To get past them, we had to go stomach to stomach.

Not long after we put to sea, we noticed members of the crew setting up ropes by all the stairs and passages. I asked if they were expecting rough weather and they allowed that this might be the case. The steward suggested that the best chance of avoiding sea sickness was to stay up on deck in the open air. On deck where there was a bar and, usually, dancing. After it got rough, I saw one couple attempting to dance, but the floor was rising and falling at strange angles and they had to give it up. One interesting phenomenon was to see a drink creep up one side of the glass and then down and up the other side.

The storm became dramatic. I got up on deck and wedged myself in the highest place I could find, facing forward. We cut through huge waves, the enormous ship diving deep into the water and then flying up with an immense volume of water breaking over its prow.

The remainder of our crossing was rough, but we finally got to New York, where the authorities came on board to check passports and visas and inspect the chest X-rays that everyone had to present before they were allowed off the boat. We disembarked and had breakfast in New York. This cost eighty cents, an amount that at the time seemed almost ruinous when converted into British currency.

On the plane flying down to Raleigh from New York, I got into conversation with my neighbor, an Egyptian student. By coincidence we were staying at the same hotel, and we met the next day for breakfast, where we discussed the many different kinds of English spoken in the world. As if to illustrate the point, when I asked the waitress for ham and eggs, she said, “Huh?” I repeated my words with the same result. Finally I pointed to the items I wanted on the menu. My Egyptian friend watched this performance with wide-eyed surprise and then remarked, “If you cannot understand them, how can I?” When the waitress brought my breakfast, in the corner of my plate was a mess of some kind. I took it back to the counter and said, “I didn't order this.” She exclaimed, “Why them's yer grits!” Like french fries in Australia, you got them whether you wanted them or not.

I was not the only Englishman who had initial difficulty with certain American traditions. When I got to Raleigh, I heard a story about a very large park that was nearby, and during the war, it was made available to British submarine crews to rest up. A number of southern ladies had volunteered to help, and among other things that were offered to the soldiers was iced tea. This was a beverage that was totally unknown in England. It took some time to discover that out of sight of the ladies, the crew had built a fire and used it to heat up the tea, thereby making it drinkable.

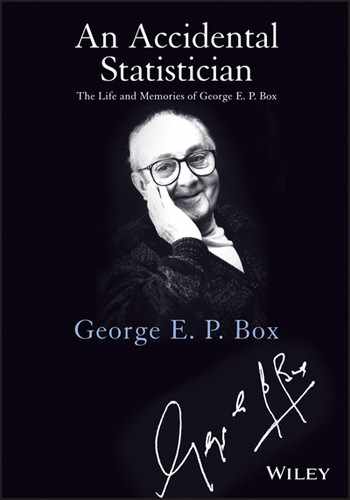

After settling into our new quarters in North Carolina, I became acquainted with Miss Cox (Figure 5.2). She was surprising: What you thought you saw was a pleasant, middle-aged lady who liked to tend her garden and bake cookies. Despite of appearances, she was a ball of fire. She had been a researcher and assistant to Professor George Snedecor at Iowa State, where the latter had founded the first department of statistics at a U.S. university. Snedecor had been asked to suggest a person suitable to head the Department of Experimental Statistics that was being established at North Carolina State, and he came up with the names of five men. When Miss Cox asked, “Why don't you recommend me?” he did, and in 1940, she went to Raleigh. When I got there in 1953, she had organized and was running the Institute of Statistics. This included a department at Chapel Hill, concentrating on theory, as well as the Raleigh department, concentrating on more practical things. She had the support of the governor and was also involved in founding the “Research Triangle,” a joint effort from Raleigh, Chapel Hill, and Duke University. She was one more example demonstrating that a woman can be an inspired leader and a super competent administrator.

Figure 5.2 Gertrude Cox.

The following story illustrates her remarkable talents. She had an offer of half a million dollars if she could find matching funds for the other half a million. She asked the help of a famous industrialist who said he would have no difficulty in raising the matching funds. There was a time limit of 12 months, but at the end of 9 months, he had failed to get the money. She said, “Okay, will you let me try?” She approached the faculty and the graduate students and explained her problem. She said, “I want each of you who is doing practical research to write up a ten-minute talk. We'll make the rounds of the big shots and see if we can raise the money.” I helped by contributing a piece on efficient experimentation and was moved to write a little ditty:

Here we come with whistle and flute,

Collecting for the Institute

She got the money!

What was taught at Raleigh and Chapel Hill was Fisherian statistics: the analysis of variance and other ideas due to Fisher. My research on response surface methods was a natural extension of Fisher's concepts applied, however, to technology rather than to agriculture. My ideas were known to Fisher who was delighted that his kind of statistics was being developed in new areas.

Unfortunately there was a graduate student who went around saying that people were wasting their time studying Fisherian statistics that had (in his mind) been superceded by response surface methods. Stu Hunter found out about this. He told me that the faculty thought that the student's opinions had come from me, and they were angry about it. Each month Gertrude had a session at her house where matters of interest were discussed, and Stu warned me that I was to be “called over the coals” at the next session. The published account of response surfaces was rather mathematical, but the basic ideas were sensible and easy to understand, so very quickly, I wrote an applied paper called “The Exploration and Exploitation of Response Surfaces” specifically for Miss Cox.2 She studied it before the meeting, and when the criticism started, she intervened and said that she thought these ideas were excellent and didn't in any way conflict with those of Fisher or with what was being taught in the department. She added that she planned to publish my paper in Biometrics, the journal of which she was editor.

The story goes that at one point Miss Cox invited both Sir Ronald Fisher and Frank Yates to present a series of lectures at North Carolina. She worked Fisher pretty hard, so he was quite glad when it was Independence Day and he was able to take off on his own with his butterfly net. But one of the graduate students had seen him and thought that now was his chance to get close to Fisher. The student found him and said, “It's a fine day.” Fisher said, “Yes.” The student said, “We get a day off—it's Independence Day.” Fisher said, “Yes.” The student then said, “I suppose you don't celebrate that in England.” At that point Fisher turned on him and said, testily, “No, perhaps we should!”

Howard Hotelling was a distinguished statistician at Chapel Hill, and at times, he could be a bit pompous. One day he came to the park to attend a department picnic driving a large new car. He asked some graduate students to drive it to a safe parking place where it would not be scratched. There were a lot of trees, and they took a long time to park it. Sometime later, the professor needed his car, but the original team of graduate students was no longer there, so another group took on the job. After a considerable time, they confessed themselves beaten. The car was completely surrounded by trees, seemingly dropped from the sky. For a long time, they were completely baffled (and this, remember, was a group of scholars, all candidates for the degree of doctor of philosophy at one of the finest universities in the country). After a considerable time, there was a breakthrough, and there were those present who felt that they should be awarded their doctorates without further delay. But no theses had been produced with pages that met the exacting requirements of proper margins and numerous signatures, so that plan fell through.

It seemed to me then, as it does now, that something new in statistics most often comes about as an offshoot from work on a scientific problem. With this in mind, during my year at Raleigh, Stu and I helped a chemical engineer with his investigations. His name was Dr. Frederick Philips Pike. He had a great sense of humor, and we got on famously. He told me that he was a distant relative of Lieutenant Pike who was the original surveyor of Pike's Peak.

Pike said that as a young man he had been anxious to visit Pike's Peak and had managed to get close to the top in his old car. He was starting on the return journey when someone opened the opposite door and sat down in the passenger seat. The newcomer wanted to be taken down the mountain, and it was evident that he was very drunk. So Pike took him along, and as they proceeded, he told Pike about his recent history. He had left home three days previously, and before he had left, he had had a violent quarrel with his wife in which neighbors and relatives had been involved.

They proceeded for some way in silence, and about halfway down the mountain, his passenger asked Pike what he did. Pike said, “I'm a mind reader.” The drunk said he didn't believe him, so Pike told him the same story that the drunk had previously related to him. As Pike suspected, the passenger had completely forgotten he had told him about this, and he began to eye Pike with deep suspicion. Finally, when Pike had driven him home, his passenger left the car, but then came back very angry and said, “I know what's been going on. There's only one way you could know all this. You must have been carrying on an affair with my wife.” At that point, he seemed dangerous and Pike quickly drove off.

In Raleigh, every morning on the radio, almost everyone listened to a disc jockey called Fred Fletcher. He was great fun. I remember, for example, that he would often play a request that was a “commercial” for Grandma's Lye Soap.” One verse I remember was about someone who

Suffered from ulcers, I understand

Swallowed a cake of Grandma's Lye Soap

Now has the cleanest ulcers in the land…

[Citation: Song goes by same title, John Standley and Art Thorson, 1952.]

If you had anything to sell, Fred would advertize it for you. I remember that for some days, there was a donkey tethered outside the station and Fred would ask for and get food for it while waiting for a purchaser. One day he advertized a piano, and I bought it for 40 dollars. It was thick with beer stains, but it didn't sound too bad.

My office was downstairs in Patterson Hall, which was where most of the graduate students were. Some of their lectures were somewhat obscure, so they would come to me for help and we became friends. Halfway through my year in Raleigh, I had to move and I asked Sid Wiener, one of the graduate students, if he could recommend a mover. (Sid always wore a cigar and was from Brooklyn.) He said, “Ya don't want to go to a movah, Professah. We'll move ya, we'll move ya.” And he organized a crew of fellow students and rented a truck, and all went well until we got to the piano. Unfortunately my new living quarters were upstairs and the stairs contained a right-hand turn. Try as they would, the students could not get my piano up the stairs and around the corner. Their gallant attempts reminded me of the famous picture of the three marines with the American flag, and they were reluctant to admit, especially to a visiting Englishman, that it couldn't be done. In the end, we took the piano to my office in the basement of Patterson Hall at the university.

I remembered that when my father had sometimes felt a bit down, he'd say, “Let's go and have a tune up!” He particularly liked to play marches. I did too. So one particular day without thinking too much about it, and forgetting I was in the South, I played “Marching through Georgia.” A janitor quickly opened my door and said firmly, “We don't play that song down here.”

It soon became clear that to get around the campus at Raleigh, I needed some kind of conveyance. When I suggested buying a bicycle, the graduate students shook their heads and told me that, like everyone else in the United States, what I needed was a car (Figure 5.3). Among them was a student from Egypt called Alex Kahlil. I told Alex I was planning to buy a second-hand car. He said that he would help me but that he was supposed to take an exam that afternoon. He suggested that if I called his professor and told him I needed Alex's help, perhaps the professor would postpone the exam and Alex could help me buy the car. The exam was postponed, and under Alex's direction, we found a car that we thought might be okay at, let's call him, Dealer A. Alex asked to take it for a trial run; however, on the way back he took it to Dealer B, who also wanted to sell us a used car. But Alex said, “We've got this car to try from Dealer A. Would you check it out for us?” Dealer B did so and told us a number of things that might be wrong with it. Then we went back to Dealer A, and we told him about these possible defects and suggested that he might lower the price, and so on and so on. I think three dealers were eventually involved in this way. After an afternoon of haggling, we got a pretty good car at a bargain price.

Figure 5.3 Jessie and our first English car (a Hillman).

The graduate students at Raleigh took some of their courses at Chapel Hill, and they took it in turns driving there in one of the university cars. A story that went the rounds was about the time when Alex drove the car. His driving was unusual in that under his guidance, the car tended to oscillate somewhat from side to side. After a bit, a police car started to follow; I think the policeman might have suspected, incorrectly, that the driver was drunk. He told Alex to stop and asked for his driver's license, and sniffed around a bit, but everything seemed to be in order. He said to Alex, “The reason I stopped you was that you were veering from side to side.” Alex said, “I'm sorry, officer, but as you can see, I'm not a native of this country. I'm Egyptian.” The police officer said, “Yes.” Alex said, “Well in Egypt, of course, you learn to drive a camel, and sitting on the back of a camel you have to allow for how they sway from side to side.” The policeman glared at him, but Alex kept a straight face, so finally the officer said, “Does anyone else in this car have a driver's license?” Someone else showed his license, and the officer said, “You don't come from Egypt, do you? Okay, then change seats with him.”

About 37 years later, I was in Egypt at a meeting of the International Statistical Institute listening to a lecture in a darkened room and someone came and sat beside me and whispered, “Hello, George.” It was Alex. He told me he had given up statistics and was growing oranges!

In North Carolina, I took some driving lessons from a woman instructor who told me I must be “slow with the hands and quick with the feet.” Later I had to have a licensed driver with me, and Stu Hunter bravely undertook the task. I think Stu became rather fed up with this, because before very long, he suggested that I take the driver's test. At that time in North Carolina, the police did the testing. I wasn't much of a driver, and on the appointed day, I was very nervous and did everything wrong. Stu witnessed my performance during the test and expressed his surprise when the policeman started to fill out a form saying I'd passed. Somewhat defensively the officer said to Stu, “Well he didn't actually break the law.”

On another occasion, when I was still a novice driver, I foolishly shot out onto a main road without stopping. A motorist who had the right of way on the main road narrowly missed me and came to a halt on the opposite side of the road. He rolled down his window. I was expecting what would have happened in England at this point: a lot of bad language. But all the driver said was, “Well, hi!”

Later, I got a flat tire one Sunday morning. A car came along with a man and his family, who were in their best clothes, and I suspect they were on their way to church. The car stopped, and the man asked what seemed to be the trouble. I was embarrassed to tell him I didn't know how to change a tire, and I asked if he could perhaps tell me how to do it. He said, “I'll change the tire for you. You watch me and you'll know what to do next time.” He got down on his hands and knees in his Sunday suit and changed my tire. I was so overwhelmed by his kindness that I didn't know how to thank him. He said, “Well you know we're all here to help each other,” and he drove away. On my return to England, when I sometimes encountered what I thought were unjust criticisms of Americans, I told these stories.

Some years later, I needed to change a tire on my car. My son Harry, who was then five years old, enthusiastically helped me change the tire, and when it was finished, he said, “Now let's change the other three.”

My year in Raleigh gave me a view of American social habits that were unfamiliar to me. Initially, my only obligation was to help Stu Hunter get his Ph.D., and during the year, I did the same thing for another student, Sigurd Anderson. Sig had recently married Sally, and Stu was married to Tady, and we had a fine time together. It started off with what my American friends called a “Round Robin Dinner” in which a number of graduate students took part. The idea was that the first course was prepared and served at somebody's house, the next course at someone else's house, and so on. It turned out that Jessie and I were responsible for the pre-dinner drinks. We had no experience in this. We knew that people in America drank cocktails because we'd seen it in the movies, but we knew nothing about mixing drinks except that they had to be very strong. What we served must have been close to neat gin, I think, because one of the ladies passed out before the first course.

Toward the end of my stay in Raleigh, Miss Cox told me we should take four or five weeks off to see something of the United States. We began by attending a conference in Canada, where a number of statisticians took the Thousand Islands boat trip. We needed gas at one point and stopped on the U.S. side. Immediately someone from U.S. immigration jumped on board and started asking us where we were from. Sigurd Andersen replied, “Denmark.” I said, “England,” and so it went. Everyone on the boat was from a different country. Finally, when Wassily Hoeffding said, in his very thick accent, “Russ-i-a,” the man shouted, “Okay, that's it! Get this boat out of here!” So went the Cold War. (I can't remember what we did for gas.)

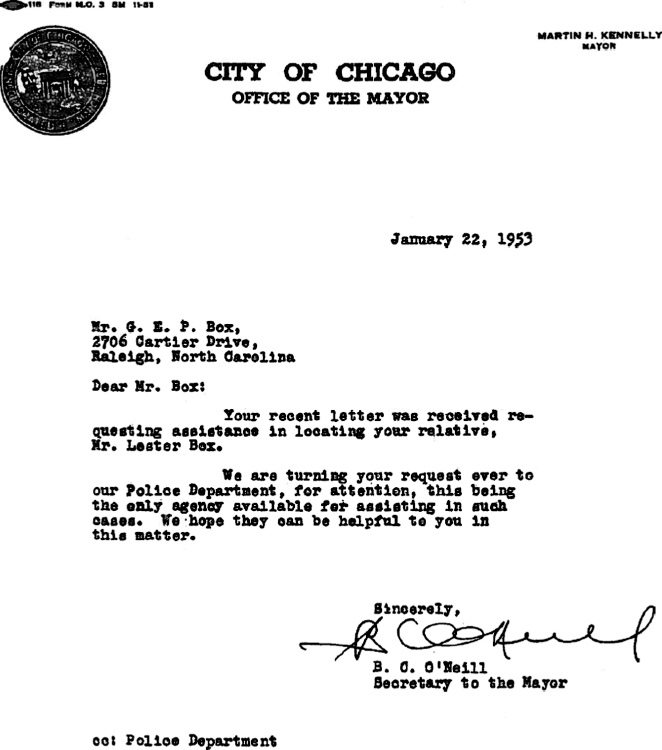

I remembered that I had two cousins living somewhere near Chicago whom I had never met. They were the son and daughter of my Uncle Pelham. I had no idea of how I might find them so I wrote to the mayor of Chicago. Very shortly I received a reply as follows:

When Jessie and I drove from North Carolina to Chicago, my driving was far from perfect, especially in congested cities. I ended up in the Chicago Loop at rush hour. I wanted to turn right, but whenever the light changed, a mass of people started crossing and I didn't see how I could turn without running them all over. Finally a policeman put his head in my window and said, “Say, buster, don't we have any colors you like?”

My cousin Evelyn was married to a lawyer who was on the Chicago city council. He was very kind and took Jessie and me to a council meeting to see what it was like. My other cousin, Lester, worked in the car industry about 20 miles north of Chicago. He had a very lively family, and while we were visiting him, we went out to go dancing at about 11 o'clock in the evening, which was rather late for us.

While in Chicago we visited an English friend, Professor Brownlee, at the University of Chicago. He was tremendously enthusiastic about the beauties of the United States, and when we said we weren't sure where to go on our trip, he invited us over to a spectacular slide show in his office. He had hundreds of slides that he had taken of his many travels, and he gave us an illustrated commentary with a map. He was particularly intrigued, and so were we, by the meandering of the Colorado River, the Goosenecks of the San Juan River in Utah, the Black Canyon of Gunnison National Park in Colorado, the Painted Desert in Northern Arizona, and of course, the Grand Canyon. We decided to follow the route that he sketched out.

After we left the traffic of Chicago, our journey to the West progressed smoothly until we were about 200 miles from the Grand Canyon. There, the car that Alex had so methodically helped me choose broke down. It took two days to fix, and the fix, unfortunately, was short-lived, for as we neared the Canyon, it broke down again. We hung about while it was being repaired and began to wonder whether this part of the trip was worth the bother. There was a cowboy-looking guy leaning on a post nearby, so I asked him, “This Grand Canyon—what's it like?” He thought for a minute, and then he said, “Well, I'll tell ya, it's just about the biggest hole in the ground you ever did see!” We went, and it was. It was also one of the most beautiful and awe inspiring sights we had ever seen.

On the trip we drove through country where there were many Native Americans living in tepees. Our friend had told us that if we wanted a chance to talk with them, we must bring a gift—an apple would do. So we stopped at a tepee and someone came out, took our apple, and then disappeared into the tepee never to reemerge.

Our journey required that we travel a long way through the desert, so we had to have a carboy full of water before we started. So much of the West was remarkable to us, but one of the most interesting sites was an Anasazi Indian village at Mesa Verde where dwellings had been cut out of the side of a cliff. These had been abandoned many centuries ago, and there were signs that the inhabitants had left in a hurry. The climate was so arid that an old woman had been found in a remarkable state of preservation after 500 years. When we went to an evening campfire show put on by the Park Service, we learned more about the culture of the Native Americans who had lived in the area. Descendents of the Anasazi danced for us and told us about the system of lookouts that had warned their people of danger—most likely to come from their enemies, the Utes. They demonstrated the call that told the cliff dwellers that “the Utes are coming!” although they allowed that this was sometimes used just to keep people on their toes.

Jessie and I very much enjoyed our trip around the United States. One day, when we were on a narrow road in the mountains, we met a massive flock of sheep that formed an impassable barrier across the road, so while I drove the car slowly forward, Jessie sat on top of the car, banging on the metal hood and shouting loudly at the sheep so that they made way for us. The Native American sheepherder looked at me appreciatively and said, “You have good woman there!”

We carried memories of this trip when we returned to England, this time on the French ship, the Île de France. On this occasion, we had a pleasant trip. I remember there were a number of French Air Force cadets returning home. One group amused itself by dropping puff balls on the dancers, testing their bombing skills by aiming for the rather expansive cleavages of the ladies below:

Upon our return to England, we bought a new car—a Hillman—but we never forgot the one that Alex helped us buy.

1 Then called North Carolina State College, part of the University of North Carolina system, which included the campus in Chapel Hill.

2 G.E.P. Box, “The Exploration and Exploitation of Response Surfaces: Some General Considerations and Examples,” Biometrics, Vol. 10, No. 1, 1954, pp. 16–60.