“The race is over! … ‘Everybody has won and all must have prizes.’”

Chapter Thirteen

The Quality Movement

Bill Hunter and I were very interested in the quality movement from its earliest days, and Bill was closely involved in bringing its techniques to the city of Madison. In 1969, Bill had spent a year in Singapore on a Ford Foundation grant that supplied sophisticated computers and professional expertise to Singapore Polytechnic, where Bill worked with faculty and students. While there, he also worked with another professor to teach an evening seminar on quality techniques for full-time workers in vital positions in Singapore (e.g., those who oversaw the harbor, refuse collection, etc.). He would later teach a similar course in Madison. Bill also traveled to Japan and Taiwan where he visited factories using quality improvement programs.

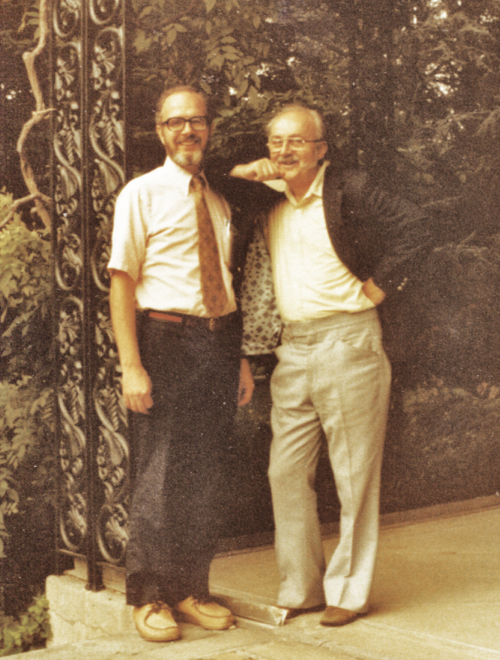

In the 1970s and 1980s, people in the United States were starting to realize that the Japanese were building cars and other products that were far superior to theirs. This was a spectacular change because before the war, Japanese manufactures had been inferior. Immediately after the Second World War, Japanese industry had been in ruins, and the United States was anxious to help Japan get back on its feet. As part of this effort, two leading experts from the United States, Dr. W. Edwards Deming and Dr. Joseph M. Juran went to Japan to lecture on quality control. Although this subject had largely originated in the West, it had been only sparingly used there. By contrast, in Japan these concepts were taken very seriously and the teachings were spread widely throughout Japanese industry. In fact, education on the principles of quality control was undertaken as a national project of the highest importance. (Figure 13.1)

Figure 13.1 Bill Hunter and me.

But as I have said, there was another factor. In the West, directors and managers seemed to believe that they already knew all there was to know about manufacturing and selling their product. The workers were thought of as disposable underlings who were there to carry out instructions. In particular, this has been the convenient rationale that has justified salaries for upper management that were spectacularly higher than those received by the workers. The Japanese philosophy, on the other hand, was that production was a joint effort in which everyone was personally involved and ideas for improvement were welcomed, rewarded, and celebrated wherever they came from. Their management was paid at a more reasonable level, and the result was that a prodigious number of ideas came from the people who were actually making the product. The methods used for quality improvement were not only those taught by their American mentors, but also those coming from Japanese workers and Japanese experts, such as Professor Kaoru Ishikawa. Because workers developed many new ideas of their own, there was a high level of morale throughout the organization.

One other important concept for quality improvement, which I addressed before, was the use of statistical experimental design conceived in the 1920s by Sir Ronald Fisher for improvements in agriculture. As I mentioned, Fisher showed that it was much better to vary several factors at a time. Fisher's approach was known in Japan as “Taguchi Methods,” named for engineering professor Genichi Taguchi. Thousands of designed experiments had been run in Japan to design optimal systems for automobiles.

In 1980, NBC broadcast a special program featuring Dr. Deming that was called If Japan Can, Why Can't We? On the show, Deming explained to an American audience that Japan's industrial success in the post-war period relied on statistical methods that would benefit U.S. companies. In Japan, Deming noted, statistical control had led to consistently good quality in a multitude of production processes. Good quality led, in turn, to better control of costs. Moreover, statistical thinking guided everyone in the Japanese production process, from line workers to executives.

The effect of these innovations in Japan was dramatic, and they were applied not only to automobiles. Sometime in the middle of the 1980s, I remember seeing a slide that asked, “What do these things have in common?” On the slide were pictures of automobiles, cameras, and every kind of technological gadget. The answer was that for each of these products, the United States had lost 50% of its market to the Japanese in the previous five years. In particular, of course, the U.S. automobile industry had been astonished and embarrassed by the clever designs and narrow tolerances of their Japanese competitors.

Eventually, Deming did get to speak to the top managers of a number of U.S. companies, and a number of senior executives in the Ford Motor Company and other industries visited Japan and discovered that one reason for the superiority of their products was the wide application of experimental design. In particular, they found that Taguchi had used statistically planned experimental arrangements to carry through what he called parameter design. Experimental design had been widely applied in England and in the United States, but only in agriculture. We are indebted to the Japanese for comprehending and demonstrating its enormous value in industrial applications.

In Madison, we started to make careful studies of what was good and not so good about Taguchi's ideas. We examined them in detail and presented a number of research reports. In particular, we found that many of the methods that Taguchi advocated were excellent, but some were not as good as standard procedures that had been developed long ago in the United. Kingdom and the United States. As a result of our studies, we suggested more efficient, and usually simpler, alternatives.

We believed that we needed to inform American industry about these matters and to work on further improvement. To accomplish these goals, in 1985, Bill Hunter and I set up the Center for Quality and Productivity Improvement (CQPI). John Bollinger, Bill Wuerger, and Bob Dye, all from the College of Engineering, worked in various capacities to secure financing and offices for the Center. Bill became the first director, and I was the director of research. In those early days, the Center had an exciting, busy, and even charged atmosphere, and our program assistant, Judy Pagel, was the rudder that kept it on course. We had been given two new assistant professors, Conrad Fung and Søren Bisgaard, who eventually became the second director.

Friendships were strong among those at CQPI, and although we worked hard, there was time for play. The atmosphere was one of a large and happy family. It was about this time that I married Claire Quist. Judy reminded me that often before we were to teach a short course, evey one at CQPI worked very late putting materials together. She reminisced about one occasion when Claire and I brought in ice cream near midnight to cheer everyone up.

Soon after we set up CQPI, Ian Hau came to the department as a graduate student. He was from Hong Kong, where he had been a soccer coach. I heard that he had been using quality techniques to improve a high–school soccer team in the town of Waunakee outside of Madison, and that he had brought the team from near the bottom of its league to near the top. I asked him to give a seminar about this, and his talk was impressive.

I became Ian's thesis supervisor, and after he took his Ph.D., he went to work for a large pharmaceutical company. I expected that he would do standard statistical work, but instead he asked the people at his company what was their biggest problem. They told him that it was the very long time taken to get new drugs approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration. After a very careful study of what happened to a specimen drug application, he discovered that much of the delay was due, not to the FDA, but to the company itself. Documents sat on people's desks awaiting attention for long periods of time and similar delays occurred in the necessary testing. Using carefully gathered data, he showed how delays in the system could be dramatically reduced by such simple devices as rerouting and attaching time labels to all documents and procedures. He then went on to solve a number of other strategic problems and in a remarkably short time was promoted to vice president.

Later on my wife Claire and I happened to be in Hong Kong when he was to be married, and I went to the wedding. The Chinese wedding was an interesting experience, but even more was to come when Ian and his wife Grace decided that they wanted also to be married in the United States. Parents play an important part in the Chinese marriage ceremony, and since his own parents were unable to come to the second wedding, Ian asked us to be “deputy parents.” It was an elaborate ceremony, and at one point, the bride and groom knelt and presented Claire and I with tea as they would have with their own parents.

When I turned 80 in 1999, I received birthday wishes from Ian in which he reminded me that Claire and I were the only ones who had been to both of his weddings. His wife, however, argued that she too had been present on both occasions.

At CQPI we developed many ideas on innovation and quality and we discussed where and when to apply them. We published our work in a new series, the CQPI Technical Reports, as well as in the statistical quality literature. We issued the first nine of our reports in February 1986.1

In 1984, Bill Hunter told me that he'd been talking to Joe Sensenbrenner, the mayor of Madison, about how quality ideas could be applied to improve the functioning of the city.2 The mayor was sympathetic to Bill's ideas and suggested, as a pilot project, to try to improve the running of the city's First Street Garage, which serviced the 900 vehicles belonging to Madison's Motor Equipment Division. He explained in particular that he received numerous complaints from the police about how long it took to get their cars fixed and that there were similar complaints regarding other city vehicles. In addition, worker morale was low and there were tensions between the union and management.

Bill worked on this assignment with Joe Turner, a foreman in the garage, and Terry Holmes, the president of union local 236 (Figure 13.2). They decided to keep a careful record for each vehicle sent in to be fixed of what and when things happened. For example, they recorded how long a vehicle stayed in the back lot waiting to get into the garage, how long it took to get spare parts, how long it took to do the repair, and how long after the repair was completed it stayed on the front lot waiting to be picked up. The data showed where improvement was most needed—by far the longest delay was in waiting for the repaired car to be picked up! Corrective action based on the analysis of data greatly improved the operation of the garage and, as Bill said, gave “employees tools for working smarter, not harder.”3 Once workers learned how to collect and analyze data, there was, in the words of Joe Turner, “more discussing and less cussing.”

Figure 13.2 Bill Hunter (center) with Joe Turner (right) and Terry Holmes (left) of the First Street Garage in Madison.

Another initiative concerned the tree leaf pickup. If you come to Madison, you will be impressed by the number of beautiful trees in the city. Each autumn the collection and disposal of millions of leaves that the trees produce requires a major effort. To get the job done, the city had been divided up into a number of approximately equal areas with a team allotted for leaf collection in each specific area. But by making a survey, Bill found that some of these areas had many trees and others had hardly any, so that some of the teams had almost nothing to do and others were rushed off their feet. Redistributing the areas so that the available people were approximately proportional to the expected amount of leaves produced a much more efficient system. You may say of these problems that the solutions were obvious. That is true, but frequently nothing is less obvious than the obvious. If this were not true, my reputation as a valued consultant would greatly suffer.

From 1972 to 1993, Madison was fortunate to have a remarkable police chief, David Couper. At the time of the anti-Vietnam war demonstrations, his approach was nonconfrontational. When hundreds of students marched down State Street, he walked with them (in ordinary dress, not riot gear). On another occasion, when he was addressing a meeting, a streaker ran across the stage. David merely shook his hand as he ran by.

Chief Couper was very interested in how quality improvement could be applied to the police department. One of the police chief's quality initiatives was directed at slowing down traffic on streets where children were likely to be, and where motorists often drove too fast. He gathered together some parents of young children, and when a speeder was stopped, a parent told the driver about his or her children, and explained how devastating it would be for the parent and for the driver if there were to be an accident.

At the time, it employed Deming's methods in municipal functions, Madison was unique in the United States, but elsewhere in the country there were factories that were beginning to use quality techniques. Bill Hunter had heard about the Motorola television factory near Chicago, which had greatly improved quality control after being taken over by the Japanese. He arranged for his class, members of CQPI, and Terry Holmes and Joe Turner to go down on a bus to take a look. The factory was still being run by the same American workers and management as before, and when we visited, there was not a Japanese person in sight. There were, however, many changes in management policy. In particular, the new philosophy was that “we, the operators, not management, are building this product and we want to take pride in the job we are doing.” We learned a great deal about the improvements that had increased quality, many of which had been introduced by members of the workforce themselves. For example, anyone could stop the line if they saw something that was awry, and there was a system of colored tabs that greatly simplified the complicated wiring of the televisions.

When we asked the line managers which system they liked the best, they said that the difference was like night and day. With the old system, almost every television had one or more faults that needed to be fixed off line. This was very inefficient, and as one manager noted, “We were running around all day putting out fires.” Flaws during production were extremely rare in the new system, as was demonstrated by a large graph hanging from the ceiling that showed a steady decline in the number of defects since the changes in management.

Bill Hunter had taught a course in the evening so that people from the local hospitals, banks, as well as industry could attend. Many of those people became leaders, encouraging quality improvements in their various fields. To coordinate these wider efforts, an organization called the Madison Area Quality Improvement Network (MAQIN) was formed in 1987.

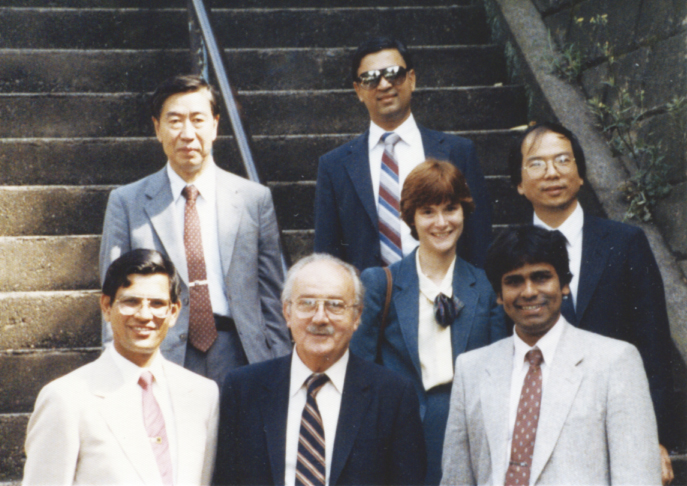

In June 1986, a group of us spent two weeks in Japan to observe quality techniques first hand (Figure 13.3). In addition to Jeff Wu and me from Wisconsin, there were Raghu Kackar, Vijay Nair, Madhav Phadke, and Anne Shoemaker from Bell Labs.4 Bill Hunter would have been invaluable company on this trip, but his fight with cancer was taking all of his strength and traveling was out of the question.

Figure 13.3 Trip to Japan.

The trip was funded by an NSF grant and Bell Labs, and our visit was greatly facilitated by Professor Genichi Taguchi and Kumiko Taguchi, as well as by Shin Taguchi, who acted as interpreter. Once in Japan, we learned about quality improvement processes, as well as about training and education, at seven Japanese manufacturing companies, and in particular at Toyota. We also visited three trade and professional organizations. Our goal was to discover how statistical techniques benefited the quality and production processes in Japanese industry.

The period we spent in Japan was enlightening from its very beginning. To our surprise, the trains ran exactly on time and our carriage stopped exactly at a prearranged place indicated on our tickets. We worried when our luggage was immediately taken from us at the station, as we were quite sure that we would have trouble finding it again, but when we arrived at our hotel, we found that each piece had been delivered correctly (to our individual rooms).

When we toured the Toyota plant in Japan, we saw the same system that we had seen in the plant that made televisions outside Chicago. A man from the American auto industry, who was also on the tour, said, “There's nothing new here. This is old technology.” He was, of course, looking in the wrong place.

Sadly, Bill's condition weakened throughout 1986. Joe Turner and Terry Holmes had become close friends with “Dr. Bill,” as they called him. At his bedside shortly before his death, they asked Bill if there was something they could do for him, and he said, “Yes, you can dig my grave.” When the time came, Joe and Terry did just that. Bill died on December 29, 1986 at the age of 49.

In October 1987, the 31st Annual Fall Technical Conference, held in Atlantic City, was dedicated to Bill's memory. Bill's wife, Judy, was there, as were his two sons, Jack and Justin. I had the great privilege of talking about my friend at the conference.

In the late 1980s, Søren Bisgaard, Conrad Fung, and I began to offer week-long short courses for industry to show how the ideas of the quality movement could be put into practice. Some of these short courses were taught on the Madison campus, others were on location at specific industries elsewhere in the country, and some took place in Spain, Sweden, Norway, and Finland. Most of our attendees were people working in industry, in particular, engineers and chemical engineers. With the support of Dean John Bollinger, we charged appropriately high fees for the courses and used the money to fund CQPI.

I met Conrad when he began the Master's program in statistics in 1975. He was among the students who took Bill's Statistics 424 class when it used as its “textbook” the mimeographed manuscript for the not-yet-published Statistics for Experimenters. He later became an excellent teacher himself, acknowledging that his method was based on Bill's excellent teaching style.

After completing the Master's degree, Conrad was a statistical consultant for quality control initiatives in manufacturing for DuPont for several years. He then returned to Madison in 1984 to work on a Ph.D. He also took over teaching a statistics course for the American Institute of Chemical Engineers that Bill had always taught. When he completed his Ph.D. dissertation in 1986, he became an assistant professor in the Department of Industrial Engineering, where he and Søren taught courses on statistical methods for quality improvement, stressing real-life applications in industrial settings.

Conrad left in 1992 to run his own statistical consulting business. He never completely left the world of teaching, however, for in addition to running his business, he is also an adjunct professor at the University of Wisconsin Master of Engineering in Professional Practice Program, which provides technical as well as managerial courses for engineers.

Søren Bisgaard and I became acquainted when he was a student in the Department of Industrial Engineering (Figure 13.4). He had had an interesting history. A Dane, he was born in Greenland and had completed an apprenticeship as a machinist before commencing his academic training as an engineer. After getting his Ph.D. at Madison in 1985, he became a valued member of the Center for Quality and Productivity. We got to know each other well and taught many short courses together. He quickly became a professor of industrial engineering, and then he directed CQPI from 1994 to 1998. In 1999, he was the principal founder of the European Network for Business and Industrial Statistics (ENBIS), centered in the Netherlands.

Figure 13.4 Søren Bisgaard and me.

Søren was extraordinarily generous. In 1987, I became ill the day before I was to give a three-hour tutorial at a meeting of the Applied Statistics Network, which was being held in Newark, New Jersey. I was in such pain that I couldn't leave my bed. Søren came over at about 9:30 that morning and sat with me while I explained what I wanted to talk about. He quickly understood it, and by 11:30, he was on his way to the airport to make the presentation for me.

I'm sure that one of the reasons Søren liked Madison was that it is situated on three lakes: Mendota, where the university is located, and Monona and Wingra. Søren and his wife, Sue Ellen, had a beautiful apartment overlooking Lake Mendota, and he kept his boat there. He was a natural sailor and handled his boat like an expert, but you never saw him do it: He would be chatting or opening a bottle of beer and never seemed to be concerned at all with the navigation of the vessel. Claire and I had many happy times sailing with him. Because he had a strong feeling against motorized boats, he was extremely reluctant to use his engine even when we were becalmed in the middle of the lake. On such occasions, it took some time to reach the shore.

Once, when we were in Stockholm together, by some happy circumstance, a friend had lent him his new sailboat. It was a gorgeous boat with fine woodwork and all the latest electronic devices. So we took off among a series of beautiful islands and soon found ourselves sailing alongside another enthusiast. Søren at once initiated a race. The boat seemed to fly along, so close-hauled as to be almost parallel to the water, and with that wonderful smile on his face, he won the race as he had won so many others in his life.

In 1988, the American Society for Quality launched a new journal called Quality Engineering. Frank Caplan was the editor, and he asked for my help. This I was happy to provide, so for all the early issues I wrote “George's Column.” The series was motivated by the idea that the most important factor in solving problems was common sense. Some titles for this column were as follows:

- Good Quality Costs Less. How Come?

- Changing Management Policy to Improve Quality and Productivity

- Teaching Engineers Experimental Design with a Paper Helicopter

- Comparisons, Absolute Values, and How I Got to Go to the Folies Bergères

Later, Søren took over the column, writing articles under the heading, “Quality Quandaries.” Many of the articles were co-written with colleagues and were later published in a book called, Improving Almost Anything: Ideas and Essays by George Box and friends.

In 2008 Søren was diagnosed with mesothelioma, and it was a tremendous loss when, after a year-long fight, he died in December of 2009 at the age of 58 (Figure 13.5). I think the poem “Sea Fever,” by John Masefield, which Claire read at his memorial service, could have been written just for him.

I must go down to the seas again, to the lonely sea and sky,

And all I ask is a tall ship and a star to steer her by,

And the wheel's kick and the wind's song and the white sail's shaking,

And a grey mist on the sea's face, and a grey dawn breaking.

I must go down to the seas again, for the call of the running tide

Is a wild call and a clear call that may not be denied;

And all I ask is a windy day with the white clouds flying,

And the flung spray and the blown spume, and the sea-gulls crying.

I must go down to the seas again, to the vagrant gypsy life,

To the gull's way and the whale's way where the wind's like a whetted knife;

And all I ask is a merry yarn from a laughing fellow-rover

And quiet sleep and a sweet dream when the long trick's over.

[Citation: From SALT-WATER POEMS AND BALLADS, by John Masefield, published by the Macmillan Co., NY, © 1913, p. 55; the poem was first published in SALT-WATER BALLADS, © 1902.]

Figure 13.5 Søren and his wife Sue Ellen shortly before his death.

Our first course, which we called “An Explanation of Taguchi's Contributions to Quality Improvement,” was offered in the spring of 1987. This was a discussion of the research that we had done on Taguchi methods in the previous five years. To our surprise, over 60 people took the course. In the CQPI office, Judy Pagel, Conrad Fung, and others often worked well into the night, to get ready for the course. Statistics courses had never garnered this kind of attention in the past. Growing interest in quality improvement methods inspired scientists working in industry to learn all they could about the most effective and efficient statistical procedures.

In the fall of 1987, we began offering our second course, “Designing Industrial Experiments: The Engineer's Key to Quality,” which became the short course we taught in Madison as well as “on the road.”

The activities of 1988 are suggestive of the enthusiasm that the quality movement engendered at the time. In January, we submitted an NSF proposal for a three-year grant on “Experimental Design and Statistical Methods for the Improvement of Quality and Productivity,” which we ultimately received. In April, CQPI brought Professor Noriaki Kano, a Japanese expert in quality management and customer satisfaction, to Madison where he also met with members of the city government and with participants in the Madison Area Quality Improvement Network (MAQIN). In the same month, we held the first of two annual quality retreats at my home, an all-day event that brought together many of the same people from city government and MAQIN. In May, the Annual Quality Congress, held in Dallas, was a “sell out.” There Conrad, Søren, Mark Finster, and I gave a tutorial titled “Modern Quality and Productivity Improvement: An Overview” that was well received. In the late summer, Søren, Conrad, and I gave our short course to 60 employees from three Hewlett Packard divisions in Sonoma County, California. In September, we repeated the course for members of the Swedish Association of Engineering Industries in Sodertalje, Sweden. From there I flew to England where I gave a talk at ICI on the uses for statistics in quality improvement. On October 12–14, we brought Professor Kano back to Madison to give two seminars. At the end of October, Stu Hunter, Søren, and I gave a three-part tutorial for the society of Manufacturing Engineers in Chicago.

Because our short courses were successful, we decided in 1990 to make a series of videotapes on the same topics. These were shot at my home in Madison by my son, Harry, who was a cameraman in Hollywood. We filmed two tapes a day for three days. These covered Quality and the Art of Discovery, The Iterative Nature of Scientific Investigation, Factorial Designs, Blocking, Simple Plotting Methods to Analyze Results, and a Practical Demonstration of a Product Development Experiment. The latter featured the same optimization strategy we used in our classes at the university, illustrating the effect of the design optimization of a paper helicopter. Søren climbed a ladder and dropped the different paper helicopters while Conrad sat below timing each flight with a stop watch.

The filming process involved a lot of different people coming and going in our home, because in addition to Harry, there were other crew members who did the lighting, adjunct camera work, and other tasks associated with the taping. At one point, Claire and I decided to escape the chaos by going out to dinner. While in the restaurant, however, Claire had an extreme bout of vertigo. She had recently been diagnosed with Meniere's disease, a disorder of the inner ear that affects balance and hearing, but previously she had never had a major attack. On this particular evening, she was so affected by vertigo that she could barely walk. We left the restaurant, and once in the car, she felt even worse. I pointed the car toward home, driving at a slow, consistent speed while avoiding bumps and potholes in the pavement. We had a number of miles to travel. Suddenly I saw red lights flashing in my rear view mirror and realized that a police car had been following us, so I pulled over. “I stopped you because you're traveling dangerously below the speed limit,” said the officer, as he inspected us for signs of intoxication. When I explained the situation, the officer gave us free passage home, but once we arrived, Claire crawled into the house and went to bed.

Some years later, Claire had another medical emergency when a drug she was taking caused an extremely painful “bleed-out” in her leg. As I drove her to the emergency room, I once again traveled at a crawl. Luck was not on our side; we were soon pulled over by a police officer who was far from understanding. After taking my license and sitting for a time in his squad car, he returned and said, “You did this before! You have a history of traveling below the speed limit.” I was reminded of the story of a fellow who had a car accident. In his written explanation, his insurance agent said, “the policy holder admitted it was his own fault, as he said he'd been run over before.”

Our videotapes are still current. They have been converted into DVDs and are once more available.

1 G.E.P. Box and R.D. Meyer, “Studies in Quality Improvement: Dispersion Effects from Fractional Designs”; G.E.P. Box and R.D. Meyer, “An Analysis for Unreplicated Fractional Factorials”; G.E.P. Box and R.D. Meyer, “Analysis of Unreplicated Factorials Allowing for Possibly Faulty Observations”; W.G. Hunter, “Managing Our Way to Economic Success: Two Untapped Resources”; P.R. Scholtes, “My First Trip to Japan”; B.L. Joiner and P.R. Scholtes, “Total Quality Leadership vs. Management Control”; S. Bisgaard and W.G. Hunter, “Studies in Quality Improvement: Designing Environmental Regulations”; G.E.P. Box and C.A. Fung, “Studies in Quality Improvement: Minimizing Transmitted Variation by Parameter Design”; W.G. Hunter and A.P. Jaworski, “A Useful Method for Model-Building II: Synthesizing Response Functions from Individual Components.”

2 See also G.E.P. Box, L.W. Joiner, S. Rohan, and F.J. Sensenbrenner, “Quality in the Community: One City's Experience,” Center for Quality and Productivity Improvement Technical Report No. 36, June 1989 (originally presented at the 1989 Annual Quality Congress in Toronto).

3 S. Reynard, “The Deming Way: Management Technique Saves Money in Madison,” The Milwaukee Journal, March 1, 1985, p. 6.

4 The six of us wrote “Quality Practices in Japan,” in Quality Progress, March 1988, pp. 37–41.