“I know something interesting is sure to happen.”

Chapter Eighteen

A Second Home in Spain

When I first visited Spain in the 1970s, it was to give short courses that had been organized by Daniel Peña and Albert Prat. George Tiao and I taught time series in Madrid, where Daniel lived, and Stu Hunter and I taught experimental design in Barcelona, the home of Albert.

I had never before realized that Catalonia is a state, for many purposes, separate from Spain, with its own language. Albert was proud of his heritage and was a wonderful guide. He was also an expert chef, and he knew a great deal about wine. Whenever we visited, he took us on a tour of all the restaurants, which while the best, were not necessarily the most expensive. (One place he took us to eat delicious seafood was down a narrow alley where there were a few people who had seemingly passed out on the ground, and I almost feared for my life.)

I remember one day, when we had a free afternoon, he asked me what I wanted to do. I happened to remember that Freixenet, a maker of Catalan champagne, was not far away. When we got there, the gate was closed and it was clearly not a day when they allowed visitors, but Albert found the gatekeeper and chatted with him in Catalan. It was like magic: We were soon shown around with almost royal treatment. On another occasion, Albert's talent as an organizer reached its pinnacle when he put on a conference in Barcelona that featured a dinner at one of Franco's former palaces, replete with strolling musicians.

The early days of my visits to Spain coincided with the end of the Franco regime. Most of our Spanish friends from Madrid and Barcelona had been in trouble with this regime as students. One of these was Agustín Maravall, who took a time series course that I taught two nights a week. He had come from Spain in 1971 to get his Ph.D. in economics. In the 15-minute break, we used to chat at the coffee machine. He told me that he had been arrested during the “troubles” and sent to a “punishment camp” for a year in Spanish Morocco. The general in charge interviewed Agustín and was happy to discover that he had studied sample surveys. The general told him that very little was known about Spanish Morocco, so he gave him a car and a couple of assistants and they spent the year making a careful survey and census.

Although Franco died on November 20, 1975, his failing health had forced him to give up being prime minister in 1973. That the fascist influence was fading became clear when the regime was openly made fun of on the television.

Franco had surprised his allies in Spain by announcing that Prince Juan Carlos should be his successor and serve as king. When Franco died, Juan Carlos not only assumed the throne but also instituted a democratic government, to the displeasure of the fascists. Tensions grew, and in 1981, fascist forces attempted a coup, bringing machine guns and other weapons into the parliament. Albert told me that he was packed and ready to leave the country at a moment's notice. But the King made a televised appeal for support, and the coup came to a quick end.

Daniel and Albert were wonderful hosts, but Spanish and American ideas about time were different. I remember the first time we were there, in the early 1970s, they invited George Tiao and me to go to dinner. We were ready at about 6 p.m., but they came for us between 9 and 10. We should have known that this would happen because we had sent them the time table for the course as it was taught in the United States, starting at 8 a.m. They wrote back saying, “You may start at 8 am, but you'll be the only ones there.” So we had to start our courses much later, with a long break for lunch, resuming in late afternoon. People went to bed late, and despite, what were for us unusual hours, they were very serious about learning this stuff. Albert, for example, had about 900 engineering students studying the Design of Experiments at his university.

In the spring of 1986, Claire and I had just flown to Madrid when someone told us that Albert Prat and Tina Roig were getting married that day near Barcelona. We flew at once to join the celebrations that had already begun in a charming outdoor hotel in a park by a lake. There were tables arranged in the garden for the many guests, and much champagne was being consumed. In fact we looked with some surprise at the stack of champagne bottles that must have measured four feet by six. None of it was labeled. I asked Albert how he had got it, but characteristically he only touched a finger to the left side of his nose and said, “I know a man.”

The origin of the champagne was not the only mystery because, shortly after we arrived, the bride and groom whispered in our ears, “Don't tell anyone, but we aren't actually married.” They had both had previous marriages, one of which had occurred in Germany. They had had a hard time dealing with the various bureaucracies, and at the last minute, there had been some technicality that prevented them from getting a marriage license on that particular day. They decided therefore to go ahead with the wedding celebrations and to get married later. But they said that since their parents were there, they were not telling anybody except for a few close friends.

For the rest of the day, there was merriment with feasting and dancing. I remember that the director of the orchestra wore a toupee that fell down when his directing became too vigorous.

Tina had a large flat in Sitges, a seaside resort close to Barcelona, and we often stayed there on weekends. Sitges is famous for its beaches. It became an artsy and countercultural mecca during the Franco regime, which it remains to this day. We were there once during the “Festa Major,” which celebrates the town's patron saint, Bartholomew. The annual celebration features a street procession with outrageously costumed participants, some wearing huge paper machê heads that dwarf their bodies. A dragon breathing real burning coals is dragged through the streets, and firecrackers explode everywhere. At one point, sparks from the dragon burned holes in the back of Claire's dress. Finally, at night, there was the finest fireworks display we had ever seen with rockets fired horizontally over the sea.

When I traveled to Spain in the 1970s and 1980s, Albert always welcomed me to Barcelona with his usual good cheer, and Daniel was an unerringly warm host in Madrid. If my experiences in Spain had ended there, I would have been content. In the 1990s, however, Claire and I were privileged to live in this beautiful country for two extended periods, and Spain became a second home.

In 1991, Alberto Luceño contacted me saying he would like to visit the department at Madison for a year (Figure 18.1). He was a professor of statistics at the University of Cantabria at Santander, on Spain's northern coast, and he was particularly interested in the work that we were doing on process control. Process control meant different things to statisticians and to control engineers. Statistical process control had been initiated in 1924 by Walter Shewhart, a physicist who was working with engineers at the Western Electric Company in Cicero, Illinois, to improve the quality of telephones. Shewhart's control chart had a line showing the process average with parallel ± limit lines. Data from the process were plotted on a chart. A point outside the limit lines indicated a possible “assignable cause”—a deviation too large to be readily explained by random variation. For such deviations, it was deemed worthwhile to look for the cause, and if it was found, to take action to eliminate it. The idea was that over a period of time, common malfunctions would be eliminated. On the other hand, engineering process control automatically adjusted the process to stay close to target. A combination of the two ideas is necessary to achieve the best control. Ultimately, Alberto and I published a book about this in 1997, and my good friend, Carmen Paniagua-Quiñones, co-authored the second edition, published by Wiley in 2009.1

Figure 18.1 Albert Luceño and me.

Alberto and his family did indeed spend a year in Madison, and he and I worked very well together. During this time, Claire and I became close to Alberto and his wife, Marian Ros, who was a physician doing research on in vitro development (Figure 18.2). We also became very fond of their eight-year-old son, Mosqui (short for Mosquito, although he is really named Alberto). This was the beginning of a long friendship, with many visits back and forth between Madison and Santander.

Figure 18.2 Marian, me, and Claire.

We were delighted to see each other again in the summer of 1993, when the International Statistical Institute was holding its meetings in Florence. Claire and I were walking across the Piazza della Signoria when Mosqui spotted us and started running, calling out to us in perfect English, “My mother is pregnant!” If this had been a secret, hundreds of people now knew it. During our time in Italy, Mosqui was a policeman, watching his mother carefully to make sure she didn't drink coffee or do anything else that a pregnant woman “should not” do.

In Italy, we once again saw Agustín Maravall, who was professor of economics at the European University Institute in Florence. He and his family lived in an apartment in the beautiful village of Fiesole, which sits in the green hills above Florence. Agustín recommended that we stay nearby, in the Villa San Giralomo, a pension run by the sisters of the Little Company of Mary. Often called the “Blue Nuns” because of the color of their habit, the sisters of the Little Company of Mary are from an Irish order that had run a hospital and a nursing home in Fiesole. The nursing home had been in the villa, which still housed a small, elderly resident population. The views of Florence from the villa and its gardens were beautiful. Less captivating but still entertaining were the shouts of the plumbers who called to each other through the floors when the plumbing failed during our visit.2

We flew from Italy to Spain, where we went to Santander for the first time. Marian and Alberto welcomed us into their home and were wonderful guides to this special region of Spain. Santander is in the Spanish state of Cantabria, near the mountains that stretch across the north of the country and reach down to beautiful beaches. The city lies on an expansive bay, and the location has a rich history. In 1589, a year after the Spanish Armada, Queen Elizabeth received intelligence (false as it turned out) that a number of ships from the remainder of the Armada were being repaired at Santander in readiness for a second try at invading England. So she sent Drake off with a good-sized fleet to take a look. Because the bay is so large, a steady wind blows in from the sea. Drake could not see anything that looked like a threat, and his captains told him that once he entered the bay, he would have great difficulty getting out. So they stayed out. Both the history and culture of Santander pulled us in, and we knew that we would be back.

I believe that it was on this same trip to Spain that we had a memorable boating adventure with Xavier Tort. He was my colleague in Barcelona who had helped with the Spanish translation of Statistics for Experimenters. He had recently purchased a sailboat and offered to take Claire and I out in it. He raised the sails a bit prematurely, and we started to drift perilously close to an escarpment. Xavier was unable to start the engine, and soon the wind was pushing us against this wall, although we were able to push ourselves away from it. Finally, as things were getting worrisome, he got the engine going and the rest of our trip was uneventful. He recently wrote to me that if the boat had crashed, “I would have become a very famous statistician (my only chance to become so), the statistician that killed George Box!!”

We saw Alberto and Marian again when they spent the summer of 1994 in Madison, the first of five summer visits that allowed Alberto and me to work together. Each time Claire and I would find a house or apartment for them to rent, and in 1994, we also found a crib and other items for their baby, “Peque,” then just a few months old (Figure 18.3). These visits were filled with happy times, with many shared meals, trips to the zoo, and spontaneous games to amuse the children.

Figure 18.3 Peque, Mosqui, Claire, George, and Alberto in Madison.

Early in 1995 I was to receive an honorary doctorate from the University of King Carlos III in Madrid. Before the ceremony, Claire and I stole a few days in Santander to visit Alberto and Marian and their children. They greeted us with dinner and champagne and took us to the small village of Silos to visit the monastery, where we heard the monks singing Gregorian chants. We also went to Haro, in La Rioja, where we visited a very old and large winery. It was our good fortune to have as our guide the owner's granddaughter who was also the great, great, great granddaughter of the founder. She was a graduate of the Department of Viticulture and Enology at the University of California, Davis, and she spoke perfect English. We walked through seemingly endless underground tunnels stacked with wine in barrels all the way. Eventually we entered a room where there was wine more than 100 years old. The room was full of cobwebs. The guide explained that this wine was undrinkable but that the spiders were encouraged because they kept down a species of fly that ate the corks.

Haro is a little village where everyone is involved with making wine. While there we went to a small restaurant for a lunch of tapas. The man behind the bar came over, took our order, and then asked what we wanted to drink. He was clearly surprised and upset when, after some discussion, we said that we didn't want anything to drink. He returned to his place behind the bar, but he was clearly offended, and after looking at us a number of times, he dived under the bar, came up with a bottle of wine, marched over, dumped it on our table, and spoke loudly and indignantly. Our friends translated this as, “Here, drink this. You can have it for nothing!”

After touring the winery, Claire wrote this poem:

The Winery at Rioja

(January 22, 1995)

the winery López de Heredia, windows

connect the office to the cellar, etched in scenes

from the south of Spain – how she would have loved

these windows I think, she and this place the same age

descend the newly swept stairs with other tourists, down

down into the hand carved cave and thousands of miles

away she died and I once drank this wine and still feel the pain -

the death of her sons, I back away from the guide's racing Spanish

resist translations, chiseled caverns alive

need no explanation – feel the walls, smell the moss, dust thick

the oak and wine invade my senses, swirling with smells

dizzy with the years of richness, I mourn the loss at home

the oak barrels few artisans left to make, the good money

not enough to offset the hard work, what will happen when coopers

are gone and the machine-made barrels feel no care or love

freed to feel the decay of this century, I enter the world of bottles

1/2 million Rioja stacked and never touched, do not disturb

their peacefulness, they have been laid to rest and will enjoy

a second life in 3 or 5 or 7 years – quiet , coated with dust, they wait

last the cementerio, the oldest bottles and Rose the mother

at their final resting, the bottles safely stacked in nichos,

glasses are carefully placed on the lid of a huge discarded cask

and at its center the first vine of this winery, dripping with age

and decay, like the bridal banquet in Dicken's Great Expectations,

yet nearby a 1987 Viño Tondonia awaits its beginning

soon it's tenderly uncorked with instructions about tasting a Rioja

some tourists serious, others snicker and ignore the sober ceremony

– in the wine I taste the oak, the grapes, the decades – death and life fill my mouth

After a few days in Santander, we all drove together to Madrid where I was to receive the honorary doctorate. Daniel Peña, who had organized this occasion, is a remarkable man (Figure 18.4). In the 1980s, he had become concerned that, although there were two universities in Madrid, there was very little available for poor people. Along with some political colleagues, he persuaded the government to build a new university. Founded in 1989, and housed initially in a former army barracks, the new university was named for King Carlos III who had been an enlightened 18th-century ruler who had promoted education and the arts.

Figure 18.4 Daniel Peña and me in Spain.

The new university has now become a great success with three campuses. It has a student body of approximately 20,000, including graduate students. The main site in Getafe, a suburb of Madrid, has an intimate campus composed of modern buildings arranged around quadrangles. The other campuses are located in Colmenarejo, in the mountains north of Madrid, and in Leganés, just northwest of Getafe. The Scientific and Technological Park at Leganés, which is managed by this university, is the largest in Spain and one of the largest in Europe. It is the commitment to technological innovation that has defined Carlos III since its inception.

There is a considerable international presence here, with seven of the graduate programs taught entirely in English. In a short time, the university had developed three faculties (Law and Social Sciences; Humanities, Communication and Documentation; and the Higher Polytechnic School). These offer over 40 undergraduate as well as doctoral programs.

I have received other honorary doctorates but not like this one. Assisted by our wives, Daniel, the Chancellor, and I got dressed up in splendid gowns with extraordinary beaded hats amid much merriment in the Chancellor's office. At the ceremony, we were led in procession by a line of musicians who played as we entered the hall, where the faculty sat solemnly arrayed in the same finery. Daniel presented me to the Chancellor, who bestowed a number of gifts upon me: white gloves to represent the “purity of my research,” a necklace, and a ring. I was also given two massive volumes that were copies of the first edition of Cervantes' Don Quixote. These symbolized the gift of knowledge.

As part of the ceremony, Daniel presented the “laudatio,” which explained why I was being given the honorary degree. In it, he detailed the usual highlights, but I was especially happy when he said, “One of the most rewarding learning experiences in my life was to attend the Beer and Statistics Seminar that George Box runs in the basement of his home in Madison, Wisconsin. … In the open and exciting discussion that follows the … talk I felt as [I have nowhere else] that science is a unique adventure that we approach from different corners [while sharing] a common method and a common perspective: the search for the truth and the understanding of the world and of ourselves.”

The ceremony in Madrid gave Claire and me the chance to see a number of dear friends. Albert and Tina came from Barcelona, and we spent happy days in Madrid with them and with Daniel and Mely, who were gracious and generous as ever. The six of us visited the majestic Escorial, at the base of Mt. Abantos, in the town of San Lorenzo de El Escorial, about 28 miles northwest of Madrid. Built of the local gray granite, the Escorial is an impressive compound constructed between 1563 and 1584 by King Phillip II of Spain. Phillip was a Catholic and a deeply religious man, and he dedicated the structure to the glory of God. A few years later, he sent the Armada to England to depose the Protestant, and in his view illegitimate, Queen Elizabeth. The formidable complex houses a monastery, a basilica, Phillip's palace, a pantheon of kings and queens, a library, a museum, extensive gardens, and an art gallery featuring paintings by Titian, Tintoretto, El Greco, Velázquez, José de Ribera, and many others.

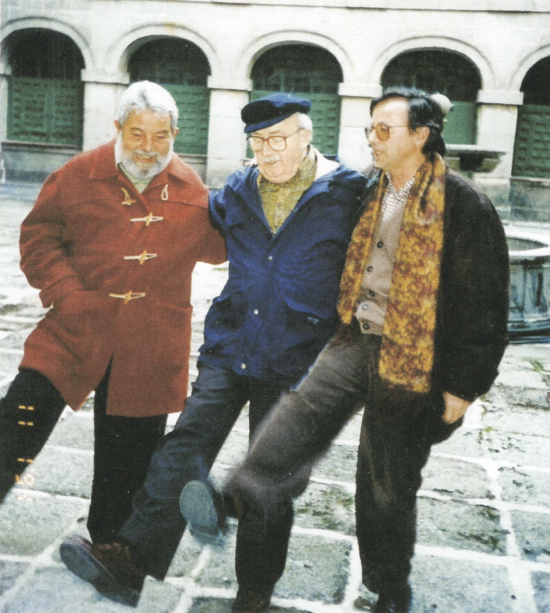

We were the only visitors that day, and we were hosted by a Dominican monk, Dr. Agustín Alonso, who was the director of the economics school there. He carried a spectacularly large bunch of keys and promised to show us anything we wanted to see. Dressed in the full habit, he showed us many treasures of this remarkable place. This was followed by a spectacular lunch in his rooms. We had a very happy time together, with good wine, and afterward found ourselves in a spontaneous line dance where we rocked to the tune of In the Mood (Figure 18.5).

Figure 18.5 Albert Prat, me, and Daniel Peña at El Escorial in Spain.

Having resolved to write a book, Alberto and I needed more time to work together than was allowed by summer visits. In 1995-1996, Claire and I spent a year in Santander, the first of our extended stays in Spain. To learn some Spanish in preparation for our first visit, Claire and I took an evening course at our local community college. After a week or two, it became clear that I was hopeless, and I gave it up. Claire, on the other hand, was a very able pupil. Once we were in Spain, she became competent in the language in a very short time. My Ph.D. student, Ernesto Barrios, who was from Mexico, came with us that year and greatly facilitated our lives because he knew the language.

Alberto and Marian found an attractive apartment for us overlooking the sea front. They also found us a remarkable cleaning lady, Conchi. She turned out to have many talents: She was an excellent cook, she could do the shopping, and she generally looked after our interests. When our toilet leaked, the landlady decided not only to replace it, but also to have the whole bathroom redone. The workmen were slow, very noisy, and smoked excessively. Conchi tore into them like a whirlwind, exclaiming that they were “disturbing the Professor!” She insisted that they not smoke, be quiet, and get on with the job. They complied.

One remarkable feature of Santander is its fishing fleet. Every day except Sunday, they go out into the Atlantic Ocean to catch a wide variety of fish that are sold in a large fish market in the city. The kitchen in our apartment was a challenge because we had just two burners and a microwave, and if we used these simultaneously, a fuse blew. There was a particular fishmonger to whom Claire had explained this situation. He was sympathetic, so on each visit, we would join the queue at his counter, and when our turn came, he would consider the problem of our culinary limitations in the light of the varieties of fish that he had at the time. After careful deliberation, he would make a recommendation and explain exactly how we should proceed to cook the chosen fish using our limited resources. This held up the queue, but those waiting mostly seemed entertained.

The sands at Santander are beautiful, and at the west end of the town, they are exceedingly wide. I've seen two side-by-side football games on the sand at the same time. To the east, however, the beach becomes narrower, and when the tide is in, the sea comes right up to the embankment.

One morning quite early, Claire and I walked down to the east end of the beach. The tide was not fully in, but when we arrived, we saw a good-looking car stranded in the sea. The rule was that no cars were allowed anywhere on the beach. Two youths had apparently ignored this and driven the car onto the sand the previous night. They were frantic. The sea had come in behind them and had cut off any retreat. The only way out was up some very steep steps.

We watched a pantomime that went on for about 45 minutes. First the police came and there was much shouting in Spanish, but no progress was made. Then a small crowd of people assembled, very voluably offering advice. Then a man who was presumably the father of one of the boys appeared. He was quite upset to see his car in a process of slow inundation by the sea. Finally the crowd had to make way for the fire brigade. Ropes were produced, and two stalwarts in galoshes attached them to the car. Eventually the car was drawn sedately by the fire engine through the sea and then pulled with great clanging up each of the steep steps. Once on the road, it was lost in the crowd, so whether it could be driven or what happened to the boys, we never discovered.

I had an office at the University of Cantabria, where Alberto taught. My Spanish never improved much, unfortunately, although communicating with professors and students presented no problem because they spoke English. But there was a woman caretaker in the building who spoke absolutely no English. After a few failed attempts at conversation, I discovered that we had both studied French in school, so we had fun speaking simple phrases to each other—sometimes surprising those around us.

A short distance from where we lived there was a convenient general shop that sold things like cigarettes, bus tickets, and candy. We became friendly with the shopkeeper who told us that he planned to take a trip to England with his wife and daughter. Claire organized a small class in English for him and his family. The man clearly wanted to reimburse Claire for her trouble so he gave her cigarettes—single packs to start with and later entire cartons. Claire didn't smoke but was hesitant to tell him, so she gave the cigarettes to Ernesto, who was a smoker. The cigarettes were American Chesterfields, and Ernesto would have nothing to do with them. His girlfriend wouldn't touch them either, so they were passed on again, and again, until they were finally accepted by someone who must have been desperate for nicotine. Two of Claire's pupils, the wife and daughter, were apt students, but like me, the shopkeeper made no progress learning a new language.

Early on in our stay we had purchased a very nice used English car—a Rover—that had belonged to a researcher who was spending a year in the United States. He had bought it from a garage owner he knew. Rover cars had an excellent reputation, and remarkably, the owner of the garage said that after a year, when we returned the car, he would buy it back from us for almost the same amount we paid for it.

On the morning we were leaving the country, I was waiting with the owner of the garage for Claire, who was bringing the car. After a time I could see a car progressing slowly down the long straight road and from it came great puffs of black smoke and a series of explosions. Quite properly, Claire had stopped at a gas station to refuel the car before returning it. Unfortunately, she had accidentally filled it with diesel fuel.

Although our book was published in 1997, Alberto and I shared many interests. So in 1998–1999, we arranged to live in Santander once again. This time we stayed in an apartment in the Hotel Las Brisas, across the street from the bay. As always, we had wonderful times with our friends, sharing meals and conversation, walking the beach and visiting parts of northern Spain. Claire and Marian were like sisters. They used to meet for coffee, as they were both aficionados of the drink. The first time we lived in Santander, Marian would speak in Spanish and Claire would reply in English. This caused a few looks from others, but it worked well for them.

By this time Peque was four, and even though Claire was making great progress with her Spanish, Peque's Spanish was improving at an even faster pace. When Peque heard something that sounded incorrect, she would say, “No, Claire, you don't say it that way.” She and Claire had many opportunities to practice, as Claire would sometimes pick her up after school when Marian had to work late, and they would make a trip to a local shop for a supply of candy.

In Spain we celebrated holidays with Marian, Alberto, and the children, and one custom for New Year's Eve that I thought was intriguing was the eating of 12 grapes, one with each of the 12 midnight chimes. This brought good luck, but I never managed to eat the grapes in time, so I will never know if it worked.

While we were in Spain, we also had visitors from home. Harry and his girlfriend, Stacey, came to stay with us and surprised us by announcing their engagement (Figure 18.6). We enjoyed touring the area with them, and they had an opportunity to explore on their own. We went to Comillas one day, a beautiful village not far from Santander. There we visited “El Capricho,” a fanciful and fun summer residence built by Gaudí in 1885–1887 and one of his earliest buildings (Figure 18.7).

Figure 18.6 Stacey and me.

Figure 18.7 Me, Gaudi, and Harry.

We have not been able to return to Spain since our last visit, but we are in close contact with our friends, whose warmth and generosity made Spain a special place for us. Today Mosqui, who is now called “Alberto,” is 28 and currently works in the film industry in Toronto. Peque, now “Marian,” is a promising student in her first year of college in Barcelona. Their parents are well and deservedly proud of their offspring. Daniel is thriving in Madrid, where he is now rector of his university. Sadly, we lost Albert Prat, who died suddenly on January 1, 2006. He was an excellent statistician and industrial consultant, and moreover, he was a fun-loving man whose generosity knew no bounds.

1 Statistical Control: By Monitoring and Feedback Adjustment, John Wiley & Sons, New York, 1997. We received the Brumbaugh Award for our paper, “Discrete Proportional-Integral Adjustment and Statistical Process Control,” Journal of Quality Technology, Vol. 29, No. 3.

2 For more on the pension and on the Blue Nuns, see L. Inturrisi, “A Monastery Stay: Expect the Austere,” The New York Times, Oct. 1, 1989.