Reprinted with permission: xkcd.com

“Perhaps no single concept is more pervasive and important in marketing than the notion of cause and effect. Marketing practitioners depend on it in the planning and implementation of programs designed to obtain responses from consumers. Ideas of advertising affecting sales, opinion leaders influencing the adoption of new products, or promotion activities producing interest and preferences for one’s wares all rely implicitly on mechanisms of cause and effect.”

—Richard P. Bagozzi1

Causation is perhaps one of the most esoteric and complicated concepts you will come across in the philosophy of science. Don’t worry, I am not going to turn into a philosopher or physicist, and dive into the nuances of causation—such as quantum theory—that have no relevance to marketing. On the contrary, causation is extremely relevant in applying scientific reasoning to marketing, as suggested in the above quote. Admittedly, some of the ideas are a little bit difficult to grasp, but the future dividends this information will pay will be well worth the investment of your time.

As you progress through this chapter you may reach a point when you throw up your hands and say, “This stuff is just too complex. I cannot possibly fully understand all the factors that are influencing my customers.” There is much truth in that statement. Markets and consumers are difficult to understand and, in most cases, we will never know them completely. But the ultimate goal in applying scientific reasoning to marketing is not so much “to get it right,” as much as it is “to get it less wrong.”

What Is Causation in Marketing?

Let’s recall the definition of causation that I introduced you to in Chapter 6:

A marketing execution X has the power to bring about an outcome Y, which means that X will (or can) bring about Y, in the appropriate conditions, [by] virtue of its intrinsic nature.2

For example, Wendy’s famous “Where’s the beef?” television commercial reportedly was responsible for increasing Wendy’s sales by over 30% in 1984.3 In effect, this commercial was partially responsible for causing consumers to go to Wendy’s to buy hamburgers. Notice I say “partially,” because there were likely other factors that played a role in the sales increase (e.g., Wendy’s added new outlets during the campaign and the US economy was growing between 4 and 5 percent yearly), but we do not know what all these other factors are. Causality is complicated. Even the above working definition of causality is incomplete. Therefore, I need to expand on this definition in greater detail.

The Intrinsic Nature of Causality

What was the intrinsic nature of Wendy’s “Where’s the beef?” advertisement that presumably “caused” this sales increase? We really do not know what it is or how it acts on consumers to influence the brands they purchase. We do, however, have an idea of what is going on. For example, a marketing action, such as the Wendy’s television commercial, affects consumer beliefs, feelings, and behavioral intentions toward Wendy’s in ways that result in the sale of more Wendy’s hamburgers. Perhaps,

• The advertisement made the Wendy’s brand more prominent in consumers’ minds so, when consumers thought of purchasing a hamburger, they more readily recalled the Wendy’s brand, which affected their subsequent purchasing behavior.

• The humor in the advertisement in some unknown neurological way triggered a positive feeling toward the Wendy’s brand, and influenced some consumers to consider and ultimately purchase a Wendy’s hamburger over another brand.

• There was a bandwagon effect. Once the media began covering the advertisement and Wendy’s rocketing sales (the actress in the commercial, Clara Peller, even appeared on The Johnny Carson Show), some consumers simply wanted to share in the experience.

• The advertisement implied that Wendy’s burgers had more beef; consumers believed that and thought they were getting more for their money.

Today, neuroscientists are exposing consumers to advertisements and using functional Magnetic Resonance Imaging (fMRI) technology to better understand how these stimuli interact with the brain and, in turn, influence consumer purchasing behavior. In one study, researchers found a “cultural effect” influencing consumers’ preference for Coke over Pepsi. The study was designed as follows:

• Researchers first determined 67 respondents’ preferences for Coke or Pepsi.

• Respondents were then positioned in an fMRI machine, shown an image, and then given a sip of one of the products.

• The visual images were either simple flashes of light, or an image of Coke or Pepsi.

• Respondents were not told which product they would sip after the flash-of-light stimuli; however, they did know that after seeing a Coke or Pepsi image that they would be given a sip of Coke or Pepsi, respectively.

What the researchers found was interesting. The Coke stimuli were more likely to activate certain parts of the test subjects’ brains that are associated with positive emotions and motivations toward an object, than were the Pepsi stimuli.

The experimental design enabled the researchers to discover the specific brain regions activated when the subjects used only taste information versus when they also had brand identification. While the researchers found no influence of brand knowledge for Pepsi, they found a dramatic effect of the Coke label on behavioral preference. The brand knowledge of Coke both influenced their preference and activated brain areas including the ‘dorsolateral prefrontal cortex’ and the hippocampus. Both of these areas are implicated in modifying behavior based on emotion and affect [the likability of an object]. In particular…their findings suggest ‘that the hippocampus may participate in recalling cultural information that biases preference judgments.’ The researchers concluded that their findings indicate that two separate brain systems—one involving taste and one recalling cultural influence—in the prefrontal cortex interact to determine preferences.4

The preliminary lesson here is that perhaps you should design advertising so that it stimulates the hippocampus in order to activate subconscious memories linking a product to positive cultural experiences, for example, enjoying a Coke with your parents at a ballgame when you were a kid.

In his book, Herd, Mark Earls puts forth a similar hypothesis regarding how culture interacts with the consumer’s psyche, thereby influencing consumer purchasing behavior.5 Anyway, the jury is still deliberating about what neuroscience can tell us about how to design advertising.

The point I want to make, though, is just because we do not know the exact neurological mechanisms by which marketing efforts

(e.g., advertising) influence consumer purchasing behavior does not mean that we cannot study the results of our efforts and gain approximate knowledge of their efficacy and the mechanisms by which they work.

Causality Is Probabilistic

Cause-and-effect relationships between marketing efforts and consumer behaviors are vexing to measure, much to the chagrin of marketers because of the following issues: (1) free will, (2) the number of factors influencing behavior, (3) errors in our measures of these factors, and (4) the fact that marketers want to predict the behavior of consumer populations, not the behavior of an individual consumer.

Free Will

First, most of us assume that people have “free will” of some kind. This, by the way, is one of those philosophical topics I am not going to explore in detail here. Rather, I am assuming that some kind of free will exists, just as I am assuming that we can achieve some kind of understanding of causation. Consequently, regardless of how or what you market to consumers, they have a choice of whether to purchase or not purchase your product; and part of that choice is entirely under the consumer’s control, regardless of how good your product is or how much you have spent on advertising.

Unknown Factors

Second, many of the factors influencing consumer behavior are simply unknown, which makes it difficult to predict how consumers will behave. For example, the consumer’s mood at the time of purchase may affect impulse purchases, or random distractions might cause him or her not to see or pay particular attention to one of your advertisements, thereby keeping a competitor’s product more prominent in the prospect’s mind. Or a retailer could simply forget to re-stock a shelf. Many of these unknown factors influence consumer behavior and make it difficult to predict.

Measurement Error

Third, even if a finite number of factors influencing consumer behavior existed, and we were able to measure them all, the measures we use contain error. For example:

• We cannot measure without error consumers’ beliefs, intentions, or feelings toward products. When you ask consumers questions about their behavior, sometimes they:

◦ Do not tell the truth (either intentionally or unintentionally).

◦ Just do not know what motivated them to purchase the product.

◦ Simply have difficulty articulating what motivated them to purchase the product.

• Moreover, the actual questions marketing researchers ask consumers in surveys and the answers consumers give do not completely and accurately reflect the beliefs, intentions, or feelings that influence their behavior. In marketing research, this is called measurement error and it is impossible to eliminate.

Predicting Market Behavior

Finally, marketers are not as interested in predicting the behavior of individual consumers as much as they are in predicting the behavior of populations of consumers—“What percentage of consumers will purchase our product?” versus “Will John Doe purchase our product?”6 Although individual consumers buy our products, we largely market to groups or classes of consumers. Therefore, our predictions of consumer behavior are statistical or probabilistic in nature.

The Nature of Causality

Notwithstanding that causality is problematic, marketers need to get their hands around this concept in order to make higher quality decisions. As I quoted Bagozzi at the start of this chapter, “Marketing practitioners depend on [having some conceptual understanding of this concept] in the planning and implementation of programs designed to obtain responses from consumers. Ideas of advertising affecting sales, opinion leaders influencing the adoption of new products, or promotion activities producing interest and preferences for one’s wares all rely implicitly on mechanisms of cause and effect.”7 As a first step toward achieving this understanding, keep in mind that there are three basic criteria for saying that one variable is the cause of another: temporal sequence, concomitant variation, and absence of other possible causal factors.8

Temporal Sequence

This criterion demands that if X causes Y, then X occurs either before or simultaneously with Y. Knowing what-came-before-what is not always easy to identify, as described by Malhotra:

For example, customers who shop frequently in a department store are more likely to have the credit card for that store. Also, customers who have a department store’s credit card are likely to shop there frequently. The time order of these variables—credit card ownership and frequent shopping—is not obvious. Did credit card ownership precede frequent shopping or did frequent shopping precede credit card ownership? An understanding of the underlying phenomena associated with department store shopping might be necessary to accurately identify time order.9

Concomitant Variation

This means that the values of X and Y need to be correlated in the direction that you expect them to co-vary, positively or negatively. Generally speaking, for example, as you increase (decrease) advertising expenditures, awareness of your product increases (decreases). Advertising expenditure levels are said to be positively correlated with brand awareness. Sometimes the correlation between two variables is negative. For example, holding all other factors constant, as a product’s price increases, the quantity demanded of that product tends to decline.

Absence of Other Causal Factors

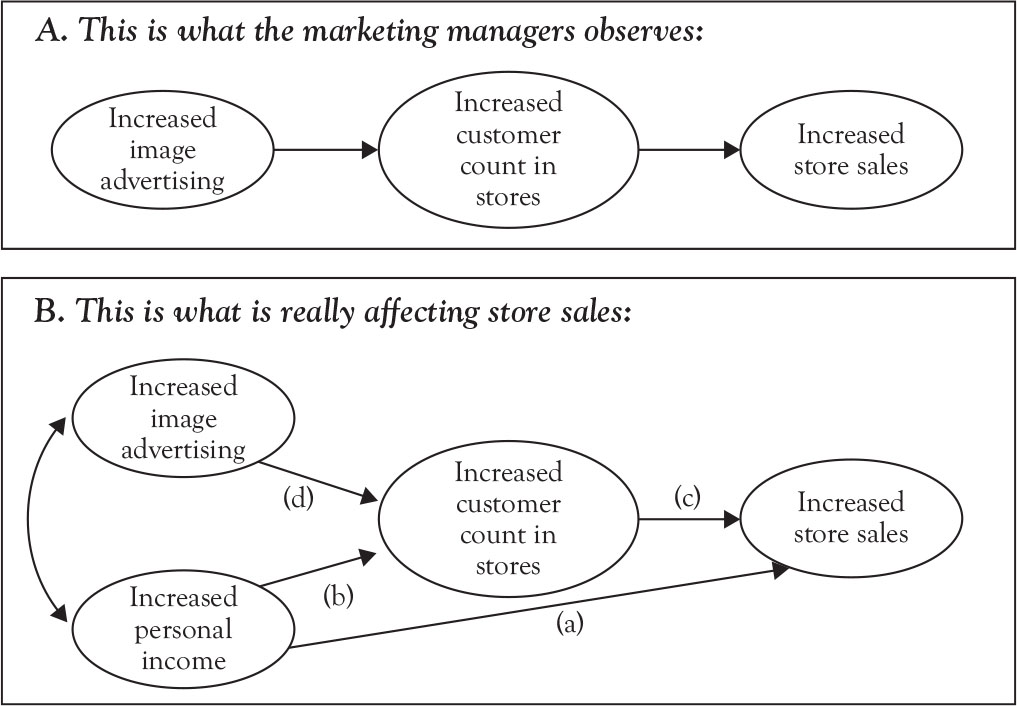

Assume that a retail store launched a new advertising campaign

12 months ago and that during this period the number of customers visiting the store increased, along with store sales. It would appear that sales increased because of the advertising. However, in marketing, the “obvious” can be misleading (see Figure 8.1A). Unless some research is conducted to identify additional factors that may have caused increased store sales, the marketer would simply assume that increased advertising caused an increase in store traffic, which, in turn, resulted in increased store sales.

If, however, during the same period in which the advertising campaign was conducted (see Figure 8.1B), consumer personal income rose (e.g., because the unemployment rate dropped and wages increased), increased store sales would likely have been caused by both the advertising and increased consumer personal income. The curved arrow between “Increased image advertising” and “Increased personal income” denotes that these two factors are correlated with each other—as advertising increased during the period, so, too, did personal income.

Figure 8.1. Example of causality.

In our example, “Increased personal income” affects “Increased store sales” both directly and indirectly as follows:

• Direct effect: The arrow pointing from “Increased personal income” to “Increased store sales” (a) is the direct “path.” For example, consumers simply have more money to spend at the store even if they don’t increase the frequency with which they visit the store.

• Indirect effect: The arrows from “Increased personal income” to “Increased customer count in stores” (b), and “Increased customer count in stores” to “Increased store sales” (c), reflect the indirect path. “Increased personal income” influences more frequent shopping, which in turn influences store sales.

By now, you should be beginning to appreciate that causality is a complex, if not a frustrating, topic. After all, most marketing outcomes, such as increasing sales and customer loyalty, are complicated and rarely caused by one factor, such as increased advertising or even increased perceived product quality. But wait, the causality story is about to get even more complicated.

Causality, Interaction Effects, and Moderating Variables

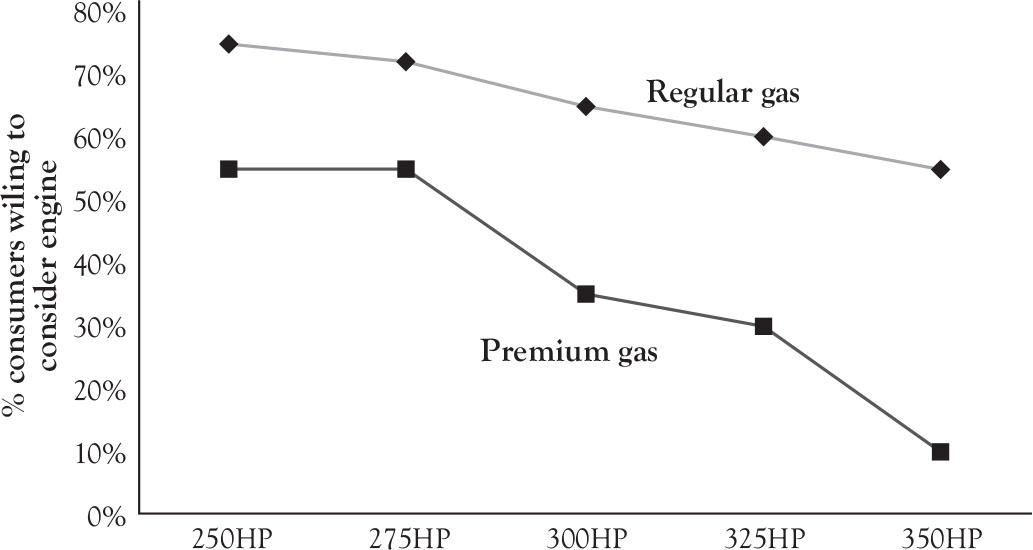

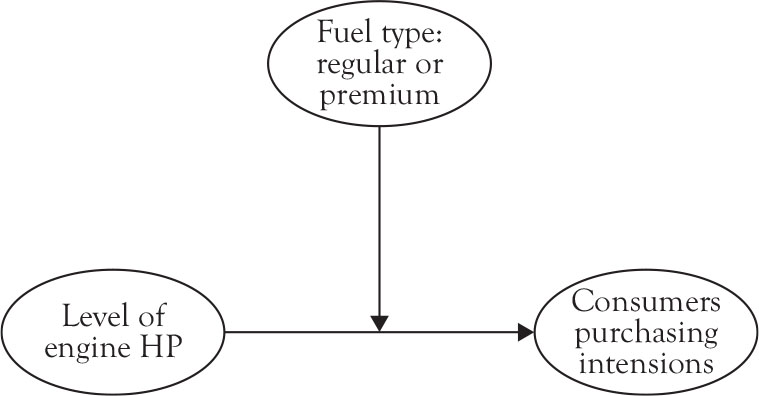

“When assessing the relationship between two variables, an interaction occurs if the effect of [one variable] depends on the level of [the other variable]….”10 For example, consider Figure 8.2. If consumers’ willingness to pay for higher horsepower (HP) vehicle engines is influenced by whether the engines run on regular or premium gas, then engine HP is said to interact with fuel type. The percentage of consumers willing to consider an engine at successively higher HPs diminishes more if the engine requires premium versus regular gas. Consequently, fuel type—whether an engine requires regular or premium gas—is said to “moderate” consumers’ propensity to pay more for higher HP engines (Figure 8.3).

Figure 8.2. Engine HP and fuel type interaction.

Below are additional examples of interaction effects:

• The effectiveness of brand image advertising interacts negatively with price promotions, when both are being run at the same time. Price promotions have been shown to lower the communications effectiveness of brand image advertising campaigns because consumers pay more attention to the promotion versus the advertising messages surrounding the brand’s image.11

• The desirability of a new color display on a cellular phone is moderated by the size of the display. If the phone’s display is not close to consumers’ ideal size, the perceived value of the color display is diminished.

• A new natural fabric in clothes that breathes and wicks moisture away from the skin could be moderated by whether the clothes made from the fabric are “permanent press” or not—the fabric may have many desirable properties, but some consumers may not want to iron their clothes.

Figure 8.3. Moderator variable relationship.

Thinking Tip

Any proper discussion of causation needs to invoke the eighteenth-century Scottish philosopher, David Hume (1711–1776), and what has come to be called “Hume’s problem of induction.” Ideas expressed in his An Inquiry Concerning Human Understanding (1748) over 250 years ago have relevance for today’s marketers. Let’s first examine this problem of induction from a general perspective, and then investigate its application to marketing.

Generally, the problem of induction states that we have no justification to believe that the patterns we have historically observed will continue on into the future. This may seem to be a ridiculous proposition since we all believe that the Sun will rise tomorrow, balls drop to the ground, and hot air rises. All we observe in nature, Hume contends, is one thing following another—what is sometimes called constant conjunction. We attribute causation to patterns we observe because of our psychological disposition to do so.

The key to understanding Hume’s point of view is to appreciate the use of the term, “justification,” and to accept the fact that, in many

situations, Hume is indeed correct. We are often not justified in assuming one event will follow another. For example, I am not an engineer and, consequently, I have no good justification to believe that my car will start the next time I turn the ignition key, other than it has done so in the past.

Many businesses stick to the same old business models, believing that what worked yesterday will work tomorrow—Kodak, AOL,

General Motors, Borders Books, Merrill Lynch, Montgomery Ward, and the list goes on. Given these companies’ attitudes, their actions necessitated their downfall, because, just as there are lawlike relationships in physics, there are lawlike, cause-and-effect relationships in marketing. For example, the “law of supply and demand”—as price goes up, quantity demand goes down—is an economic law that applies to marketing.

What, then, can marketers learn from David Hume? First, do not assume that what worked yesterday will work tomorrow. Second, and to the extent possible, seek to understand the cause-and-effect relationships in the markets you serve. Finally, be ever vigilant in questioning the premises under which your marketing strategy is founded. For example, on November 10, 2011, Adobe Systems announced that it was jettisoning its 15-year investment in its “Flash software format for use in the browser programs that come with smartphones and tablet computers…and increase[ing] its support for HTML5, a collection of technologies backed by Apple and others such as Google Inc. and Microsoft Corp.”13 David Hume would be proud.

Necessary, Insufficient, and INUS Conditions

A single factor or group of factors (a group of factors = a “condition”) may be either necessary or insufficient to influence a consumer to consider a brand. There are always some necessary conditions that have to be met for a consumer to consider a product. Clearly, if consumers cannot find a product, they cannot buy it. Product availability (X) is a necessary condition for purchase (Y ). X, however, may be a necessary condition, but it may be insufficient by itself to bring about a purchase—the product also needs to be competitively priced—making X both a necessary but an “insufficient condition” to motivate purchase.

Most causes of consumer purchasing behavior can be attributed to INUS conditions—insufficient necessary unnecessary sufficient, as explained by Richard Bagozzi (italic supplied):

As an example, let us examine the claim sometimes made by marketers that brand image (measured by the brand name) affects the perception of quality. When marketers make this claim they are not saying that the brand image is a necessary cause or condition for the attribution of quality. One may judge a product as high or low in quality without knowing the brand. Similarly, marketers are not claiming that the brand image is sufficient for the perception of quality since one must at least attend to, be aware of, and evaluate the brand name before such an attribution can be made. Rather, the brand image may be regarded as an INUS condition in that it is an insufficient but necessary part of a condition that is itself unnecessary but sufficient for the result. Many of the causal relations investigated by marketers are of this sort.12

The gist of Bagozzi’s explanation is that many of the causal relationships that marketers believe exist are more complicated than one might initially think. Often these causal relations are part of these more complex INUS conditions.

For example, assume that you are a marketing manager for the Acme lawnmower manufacturing company. Under what condition or conditions will consumers consider the Acme lawnmower brand? It is a fair

assumption that, for one, consumers must perceive that your lawnmower is competitively priced. Although this is necessary, it is insufficient to prompt consumer consideration because consumers want more than just a competitively priced lawnmower. They may also want a particular kind of mower deck or a certain level of engine horsepower (HP). Therefore, being perceived competitively priced is an insufficient but nevertheless a necessary condition for consumers to consider Acme. This, then, is the IN of the INUS acronym. What is the US? Consider the table below in which we explore whether John Doe will consider an Acme brand lawnmower.

|

Acme product |

Price of lawnmower |

Is price perceived competitive? |

Mower deck material |

Main retail channel |

Engine HP |

Will John Doe consider the Acme brand? |

|

Model #1 |

$300 |

Yes |

Steel |

Home Depot |

5.0 |

Yes |

|

Model #2 |

$350 |

Yes |

Polymer |

Home Depot |

4.5 |

Yes |

|

Model #3 |

$275 |

Yes |

Steel |

Home Depot |

4.0 |

No |

As stated earlier, John Doe will only purchase what he considers to be a competitively priced product, making price a necessary condition for consideration. Acme manufacturing has three products on the market that meet that criterion—Models #1, #2, and #3. John Doe does not consider #3, however, because its engine HP is too low. Therefore, being perceived price competitive is insufficient for John Doe to consider Model #3.

Now, review the product offerings reflected in Models #1 and #2. These models are unnecessary but sufficient to prompt John Doe to consider the Acme brand for the following reasons:

• Model #1 is unnecessary to prompt John Doe to consider the Acme brand if Model #2 is available and vice versa.

• If Model #1 is available, but #2 is not, #1 is Sufficient for John Doe to consider the Acme brand, and vice versa.

Therefore, perceived price competitiveness is part of an INUS condition describing alternative product offerings that would influence John Doe to consider or not consider the Acme brand.

The primary implication of INUS conditions to marketers is the following: The task of understanding cause and effect as it relates to consumer purchasing behavior can be complicated because no single factor influences a given consumer to consider your brand. You may have a competitively priced product, but price generally interacts with other aspects of your product offering in affecting what the consumer considers and ultimately purchases. Bottom line: Do not think about how you can optimize a particular attribute of your product offering, but rather focus on how to optimize a system of product attributes that, working together, can influence consumer purchasing behavior.

Now What?

If you are like me, the more you learn about causation, the more daunting and problematic you will find the prospect of trying to understand it—especially in the context of marketing: “What causes consumers to behave the way they do regarding my particular product or service, and what can I do as a marketer to influence it?” The first step in applying scientific reasoning to marketing is simply to recognize the following:

• Understanding what causes consumers to behave the way they do is not a simple undertaking. I cannot tell you the number of clients I have worked with over my 35+ years of marketing experience that mistakenly felt a simple direct mail campaign, a refreshed loyalty program, or a new television advertising program would increase sales and profits.

• Consumer behavior is caused by many factors and INUS conditions.

• Your initial impression of what you think is causing consumers to behave the way they do, and what you can to do to influence it, is probably wrong. Reflect on the H. L. Menken quote in Chapter 2: For every complex problem, there is a solution that is simple, neat, and wrong.

There is only one way to get your hands around this issue of cause and effect in marketing—or in any science or social science for that matter, and that is

To develop theories that help you to explain and predict consumers’ purchasing behavior.

Learning how to develop a theory is a lot like learning a foreign language. Before you can write a paragraph in your new language, you have to possess a basic vocabulary and learn some fundamental rules of its grammar. Analogously, before you can gain a preliminary understanding of how to develop a theory and apply it to decision making, I need to introduce you to two additional concepts: The Coherence Theory of Empirical Justification and Logic, which follow in the next two chapters.

Chapter Takeaways

1. “Perhaps no single concept is more pervasive and important in marketing than the notion of cause and effect.”14 If marketers want to influence consumer purchasing behavior, they need to possess a basic understanding of causation.

2. Causation is complex. The most we can hope for in our quest to understand consumers is a basic understanding of the factors influencing their purchasing behavior. A total understanding is impossible because of “free will,” the number of factors influencing behavior, errors in our ability to measure these factors, and the fact that marketers want to predict the behavior of populations of consumers, not one person. In marketing, causation is necessarily probabilistic in nature, not deterministic.

3. For X to be considered a cause of Y, (a) X must occur either before or simultaneously with Y; (b) X must be correlated with Y, positively or negatively; and (c) the relationship between X and Y cannot be spurious (e.g., X and Y are not being caused by a third variable).

4. Often it is difficult to uncover the relative influence one marketing variable has on another because of confounding relationships. Advertising may increase sales, but sales could also be influenced by other factors such as rising household incomes, or perhaps a competitor’s shipments cannot keep up with demand, thereby boosting your product’s sales.

5. Interaction effects complicate our understanding of cause-and-effect relationships in marketing. Consumers may desire higher HP engines, but only if they consume regular gas.

6. Marketers need to differentiate necessary from sufficient conditions with respect to a marketing action’s effect on consumer purchasing. Often a product feature such as perceived product quality is a necessary but insufficient condition to influence a consumer to consider your brand.

7. The relationship between necessary and sufficient conditions can become complicated as our discussion of INUS conditions shows. Consequently, do not think about how you can optimize a particular attribute of your product offering, but rather focus on how to optimize a system of product features that, as a whole, can influence consumer purchasing behavior.

8. Remember the lesson of David Hume. We cannot expect that what worked yesterday will work tomorrow. Always question and challenge the premises underlying your business model and marketing strategy.

9. To understand cause and effect in marketing, marketers need to be like scientists in developing theories of their markets. Theories help you explain and predict marketing phenomena.