An Introduction to Scientific Reasoning

Most of our so-called reasoning consists in finding arguments for going on believing as we already do.

—James Robinson

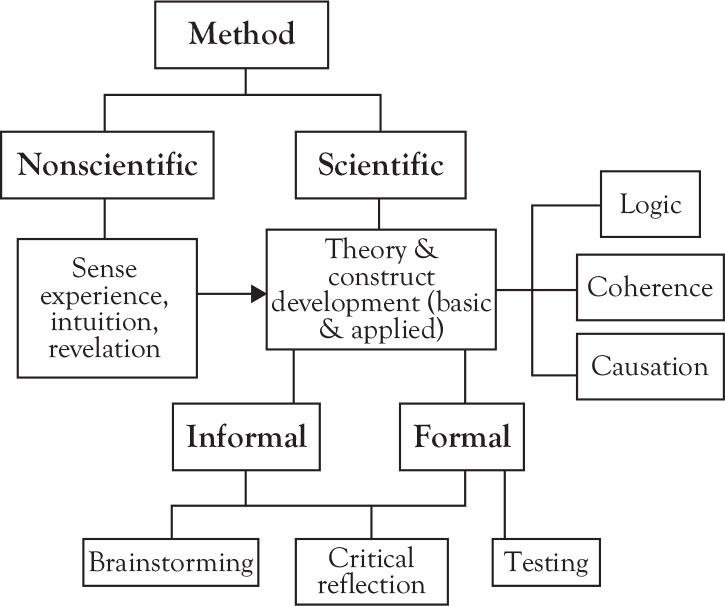

The chapters in Section II delve deeper into the subject of scientific reasoning and introduce you to some concepts that, on first exposure, you might find difficult to grasp such as construct, causality, and coherence; however, as you become more familiar with them, your scientific reasoning muscles will become stronger. See Figure 6.1, which I am using as a pedagogical tool to explain how scientific reasoning can be applied to solving marketing problems.

Figure 6.1. Approaches to marketing knowledge.

Let’s start at the top of the figure and define the term method as an approach, technique, or process of doing something. In the context of our discussion, we are talking about a method for creating and justifying knowledge—that is, developing propositions about markets that are “strong” as opposed to “weak.”

There are two basic knowledge creation methods: nonscientific and scientific. Our focus is on scientific methods, which, in large measure, are based on the development of theories to describe, explain, and predict marketing phenomenon. Theories are informed by empirical research (i.e., “testing”), logic, coherence with other reputed theories, hypotheses about causation, brainstorming, critical reflection, worldviews, and even intuitive theories or hunches. Above all, they are also based on good reasoning—reasoning that is truth-conducive.

The Scientific Method

Methods for creating knowledge can be divided into two categories—nonscientific or scientific. This dichotomy should not be confused with an ongoing debate in the philosophy of science relating to the “demarcation problem,” which is defining the difference between a science versus a pseudoscience. A “pseudoscience is a claim, belief, or practice, which is presented as scientific, but does not adhere to a valid scientific method, lacks supporting evidence or plausibility, cannot be reliably tested, or otherwise lacks scientific status.”1 One of the more contentious of such debates in the popular press these days is between the theory of evolution, which is a science, and creationism, a pseudoscience. This book does not address that debate.

Moreover, “Unscientific is not the same as nonscientific, the first carrying the overtone of something being sloppy in its analysis [of which none of us want to be accused], the second meaning that it has no pretense of being scientific in the first place.”2 Our focus here, of course is avoiding the latter—reasoning that is not scientific. If you are not reasoning scientifically, you are reasoning nonscientifically. There is no middle ground.

Nonscientific Methods

I am not going into much detail in explaining the nonscientific side of this dichotomy since how one approaches, thinks about, and acts on a problem or issue, nonscientifically, is the opposite of scientific reasoning. I include under the heading of nonscientific methods uncritically evaluated sense experience, intuition, and revelation.3 In short, “no scientific method, no science.”4 Other examples of nonscientific methods I’m sure you’ve heard about are tea-leaf reading, astrology, mystical experience, and numerology.

Although these nonscientific methods are not knowledge-conducive, they can generate ideas that subsequently can be tested scientifically. Reportedly, “August Kekule’s somnolent vision of a snake biting its tail…supposedly revealed the true structure of the benzene ring [molecule] to the German chemist.”5

Scientific Reasoning and Theory

Truth-conducive theory development is based on good scientific reasoning and is informed by sound logic, coherence with historically successful theories, and, often, the notion of “causality”—“What causes consumers to purchase the brands they do?” Theory development occurs on two levels—basic research, the kind of research you most likely associate with university professors; and, applied research, the kind of research organizations with marketing research budgets conduct. This does not mean that organizations cannot benefit from basic research—a topic I discuss in Chapter 12 on theory development. Additionally, not all scientific theory is concerned with causal explanations. In physics, for example, Einstein’s “theory” of gravity is more a description than a causal explanation—gravity is “warped” space–time brought about by matter interacting with space, but what actually causes this phenomenon is unknown. In marketing, we are interested in understanding and describing consumers’ mental states that influence behavior, although we cannot necessarily explain how these mental states come into being.

Theories may vary from being unwritten, but nevertheless reflecting a specific and well-founded point of view to formal statistical models that marketing giants such as General Mills and Proctor & Gamble are noted for creating. Theories are refined over time via empirical testing. For example, The Nielsen Company has continually refined its BASES forecasting models—which are really mathematically based theoretical models—enabling clients to predict new product sales volumes from product concept tests (e.g., using feedback from consumers about a new product prior to launch, to predict that product’s future sales).

Theory and Construct Development

We defined a theory earlier as your best explanation for a current or expected marketing phenomenon. The next chapter discusses what a “construct” is and the role it plays in theories; however, I want to give you a working definition of that term now, since I just introduced it to you for the first time in Figure 6.1. First, a little background.

To think scientifically, you need to realize that most of the phenomenon we observe in nature, and in markets, is partially or totally caused by stuff we cannot observe or identify with our five senses. DNA, which we cannot see, causes your hair color, which we can see. Tectonic plates, hidden beneath Earth’s crust, cause very observable and beautiful mountains. Similar to DNA and tectonic plates, consumer beliefs, feelings, and intentions are aspects of human consciousness and cannot be directly observed, yet they greatly influence the brands consumers choose to purchase. The thrust of most scientific research since the turn of the twentieth century has focused on how such unobservable entities give rise to the observable reality we experience every day.

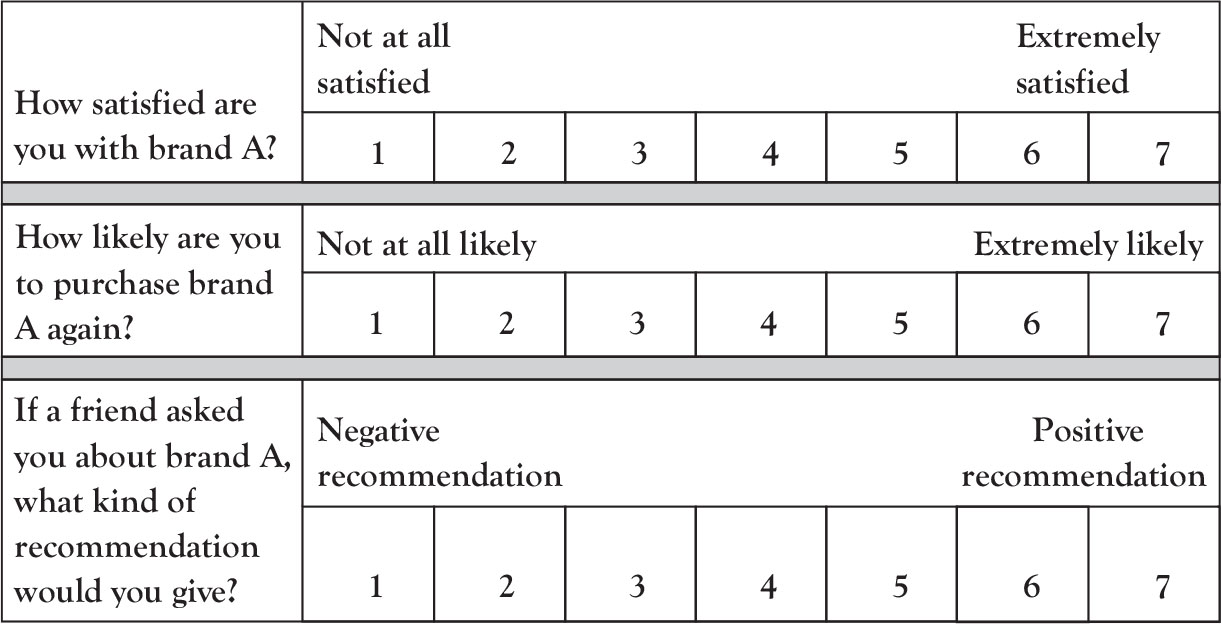

Because consumer beliefs, feelings, and intentions are not directly observable, marketers and marketing researchers develop constructs such as Brand Loyalty, Perceived Product Quality, and Brand Equity to help us understand how the mental states that these constructs describe influence brand choice. For instance, if you have ever talked to your customers, you may have asked them if they are satisfied with your product, and why. Constructs, then, “are abstractions: mental images or representations of intangible things that are thought to exist but not in a material or physical form.”6 “Satisfaction” is such a construct. We learn about these constructs and how our companies and products perform on them (e.g., “How satisfied are our customers?”) by asking consumers questions. For example, you can get a qualitative understanding of how loyal a consumer is toward a particular brand (say a brand of bar soap) by asking her a small sample of questions such as the following:

• How satisfied have you been with Brand A?

• What has led to this satisfaction or dissatisfaction?

• Would you purchase Brand A again? Help me understand your answer.

• Would you recommend Brand A to a friend? Help me understand your answer.

You can get a quantitative understanding of loyalty toward the brand by asking a larger, representative sample of that brand’s customers closed-ended questions such as the following, in which customers rate the brand on a series of items that reflect the Brand Loyalty construct (see Figure 6.2).

Figure 6.2. Example of quantitative measures of brand loyalty.

The next chapter discusses the idea of a construct in greater detail.

Logic

“Logic is the study of what counts as a good reason for what [something is], and why [something happens].”7 There are two broad categories of logic: deductive and inductive. At the beginning of this book, I gave a deductive argument supporting the view that marketers require knowledge (recall that an argument is a set of statements composed of a conclusion and the premises that support it):

Premise A: Effective decision making requires knowledge

Premise B: Marketers want to make effective decisions

Conclusion: Marketers require knowledge

Here is an additional argument with respect to scientific reasoning:

Premise A: Effective decision making requires one to possess good scientific reasoning skills

Premise B: Marketers want to make effective decisions

Conclusion: Marketers require good scientific reasoning skills

Deductive logic requires that the premises of an argument, if true, guarantee the truth of the conclusion. I believe that you’ll agree that the premises in the above arguments are true and the conclusions valid.

In the social sciences, there are few (if any, really) deductively derived arguments. I will elaborate on why this is the case in more detail later; but for now, here is the short answer: consumer behavior is not deterministic and the information we have on consumers and markets are incomplete and not 100% accurate. Consequently, it is impossible to lay out a set of circumstances and then deductively predict how 100% of consumers in a given market will behave.

The second kind of logic is inductive, and takes the form of inductive arguments. Induction can be defined narrowly and broadly. The narrow definition simply states that patterns we observe will continue to repeat themselves: “The sun has always risen in the past. The sun will rise tomorrow.” This is the problem that tripped up Nokia. Management felt that their brand equity in consumers’ minds would protect their US market share in the early 2000s. Then Motorola’s Razr came along.

The broad definition of an inductive argument is, simply, any inference that is not deductive. For instance, if you conduct a marketing research study that suggests 50% of a given market will purchase your new product, that conclusion is based on inductive logic. No matter how much research you did on the topic, the premises supporting your proposition do not guarantee that 50% of a given market will purchase the product—that’s why the conclusion is inductive. To the chagrin of all marketers, inductive arguments can be wrong because of reasons cited earlier: consumer behavior is not deterministic and the information we have on consumers and markets, which form the premises of a marketer’s argument, are incomplete and not 100% accurate.

Coherence

Generally, theories should be in agreement with, or “cohere with” other widely accepted and successfully tested theories. For example, assume that you work for a company that sells contact lenses, and based on your personal experience and knowledge of this industry, you believe that in order to get a new contact lens product adopted, you feel that the following steps must take place:

• Step 1: Build product awareness of the new contact lens brand

• Step 2: Build interest in the brand

• Step 3: Motivate trial

• Step 4: Product will be adopted if it is perceived to offer more value (sum of benefits minus costs) than a consumer’s currently used contact lens brand.

This is your informal “theory” of how your new contact lens product will be adopted. But do your beliefs “cohere” with generally accepted theories about product adoption? Here then is the question you should ask yourself if you are applying scientific reasoning to solving your marketing problem:

“Is there any generally accepted marketing theory that supports my belief about how some new products are adopted by consumers?”

The answer is “yes”—the innovation adoption model of the consumer response process coheres with your personal theory.

This model represents the stages a consumer passes through in adopting a new product or service… it says potential adopters must be moved through a series of steps before taking some action (in this case, deciding to adopt a new product). The steps preceding adoption are awareness, interest, evaluation, and trial. The challenge facing companies introducing a new product is to create awareness and interest among consumers and then get them to evaluate the product favorably. The best way to evaluate a new product is through actual use so that performance can be judged.8

This model works for some product categories. For example, Johnson & Johnson offered a “free trial pair” certificate in promoting its Surevue® and Acuvue® disposable contact lenses.9 The model does not work well for all product categories—such as those that consumers do not purchase repetitively and are relatively expensive (e.g., houses, computers, or cars), or possess a high degree of trial or adoption risk, such as a company switching major computer systems. Bottom line: in many cases, your best theory of a particular market or market situation should be coherent with other generally accepted and successful theories in marketing.

Causation

First a little story. I had two philosophy professors review my book’s discussion of causation and, after reading it, both had a little smile on their face and said something to the effect, “You’re in deep waters here, Terry. Any definition you offer your readers of causation, a philosopher could give you a counter example and show that it is false!” Both my friends, however, did agree with me that marketers need a useful working definition of causation if for no other reason than to do their jobs. So I offer the following definition, which has credibility in the field of social science (which meets the “coherence” requirement discussed above), and will serve as a useful tool in my discussion of causation in marketing:

X has the power to “A” means X will (or can) do A, in the appropriate conditions, in virtue of its intrinsic nature.10

For example: X could be any element of your marketing mix such as a sales rep, an advertisement, a promotional program, or even a new store location; and A is a consumer purchasing your product. For instance:

Our new sales rep (X) has the power to persuade purchasing agents to consider our brand (A) in the appropriate conditions (the purchasing agent agrees to meet with our sales rep) by virtue of its intrinsic nature (the ability of a sales rep to use professional selling techniques to encourage purchasing agents to consider our brand).

This of course is an oversimplification of causation because, in part, “human behavior is over determined: multiple conditions are separately capable of bringing about an event [e.g., the sale of a product], so that none of the circumstances is singly necessary, even though one of the set of circumstances is necessary.”11 (This is a complicated issue that I discuss at length in Chapter 8). Additionally, in the above example,, you need more than a good sales rep to persuade a purchasing agent to consider your product. You also need a good product at a competitive price. Lacking any single necessary condition, a sale will not be made. For example, drawing from my personal experience, when I interviewed Jack, a successful business man and Tampa, Florida resident, regarding what motivated him and his wife to purchase a Regal “Sportyacht,” he identified the following influential factors:

1. A trusted friend recommended the Regal brand

2. The local boat dealer had a good reputation

3. The dealership was locationally convenient

4. The dealer had the kind of boat Jack and his wife were seeking

5. At a good price.

Absent any one of these factors, Jack said he likely would have purchased a competitor’s boat. Causation in marketing is not simple.

Scientific Reasoning and Marketing Research

Some of this book’s readers work for organizations that do little if any marketing research. Yet, you can still apply scientific reasoning to solving marketing problems. As I’ve said, it is better to apply scientific reasoning to solving marketing problems than doing research unguided by scientific reasoning. Why? Because doing the latter often results in management asking the wrong questions; and, asking the wrong questions and expecting the right answers is a form of managerial insanity. For example, Chapter 2 introduced you to the difference between “important” versus “determinant” product attributes. An important product attribute is one that consumers desire; however, a determinant attribute is one that not only consumers’ desire, but also one that influences consumers’ purchases. For instance: consumers desire driver-side airbags, but since all vehicles now have them, other factors that differentiate vehicle brands such as styling or certain performance features will influence brand choice.

Good scientific reasoning, therefore, demands that we understand and clarify our terms. If you base marketing strategy on what research tells you are merely “important” product attributes—let’s call this the “What’s-Important-Strategy”—your plan is bound to fail. In contrast, if you seek to understand the factors that determine customer behavior, you are much more likely to succeed—even if you cannot do formal research to investigate these issues. As discussed earlier, Apple’s Steve Jobs is an excellent example of a CEO who did not much believe in formal marketing research. “The company doesn’t interview consumers about what they want in the next generation of products; instead, Apple challenges its designers to come up with dramatic visions for what products can do.”12 Just look at how Jobs transformed Apple since he resumed his leadership position at the helm of Apple in 1997, when Apple’s sales were $7.1 billion and net profits were in the red (-$1.0 billion) versus sales of $65.2 billion in 2010, and profits were profusely dripping black ink at $14.0 billion.13

While director of Consumer Insights at Brunswick, I had the opportunity of interviewing a few senior executives at Premier Marine, Wyoming, MN, and learned that this very successful pontoon boat (aka floating party barges) manufacturer does not conduct formal marketing research studies—indeed, they are a little cynical about what formal marketing research can tell them. Their success is reflected in being the recipient of the National Marine Manufacturers Association’s CSI Award for Excellence in Customer Satisfaction for the 2011 program year—the seventh consecutive year they have received this prestigious honor. I can tell you that even though they are formal marketing research “non-believers,” they do conduct informal research and apply scientific reasoning principles to the management of their Company.

Figure 6.3. Premier’s uniquely designed center-toon.

Premier is a very customer-focused organization. Through discussions with its dealers, Premier customers, and conducting informal research at boat shows, management realized that a pontoon-performance consumer segment existed, whose needs and wants were not effectively being met by any manufacturer. As we will discuss in a later chapter, the Company had developed a point of view (e.g., an informal theory) of how the pontoon market was structured, and how it was divided into different market segments of consumers, one of which was the high-performance segment that they targeted. The Company made a significant investment in investigating how the design of the “toons”—the “floats” or pontoons that contact the water—affected boat performance, and their research (and the laws of physics) directed their attention to the design of a pontoon boat’s middle-toon. They eventually hired the well-known racing boat engineer Fred Cotey, who invented a uniquely designed center hull that delivers unparalleled pontoon boating performance.14 Most of Premier’s competitors only offer undifferentiated “cookie cutter” hulls, and consequently, don’t have the same market share that Premier has in this particular pontoon segment.

To be clear, empirically testing an organization’s marketing theories is a critical part of the scientific method and approach, and as a marketing research consultant and former marketing research lecturer at a major university, I am not trying to “de-market” my product. Marketing research, however, is not a sufficient condition for sharpening one’s scientific reasoning skills. As I have said: it is better to apply scientific reasoning to solving marketing problems than doing marketing research unguided by scientific reasoning.

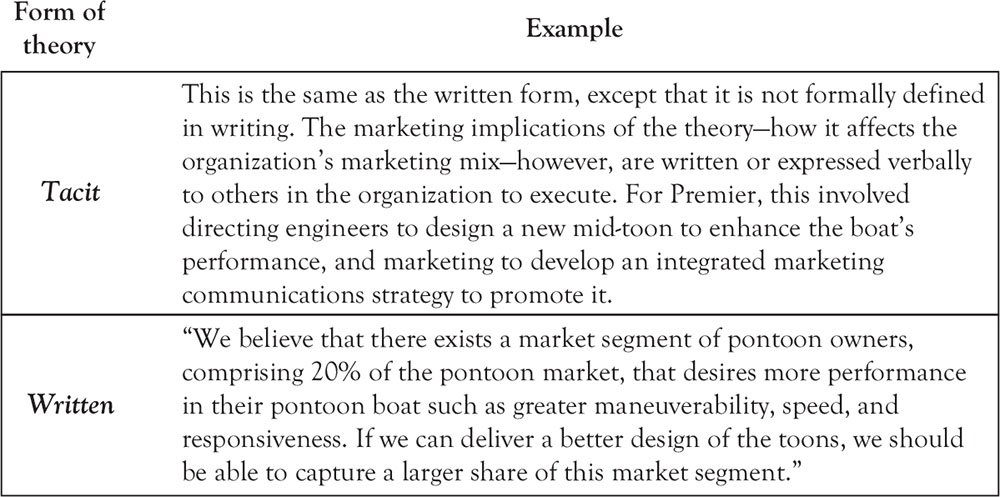

Informal to Formal Theories

Theories can range in formality from unwritten or tacit theories—such as Premier Marine’s unwritten theory of how the pontoon market was structured and the opportunity it felt existed in the pontoon performance segment—to theories expressed in written, graphical, and, ultimately, statistical form, the latter being what you would expect to read in academic journal articles. My focus in this book is primarily on tacit, written, and graphically represented theories. The Premier Marine example (hypothetically) could take on these forms as depicted in Figures 6.4 and 6.5.

Figure 6.4. Tacit vs. written examples of a simple theory.

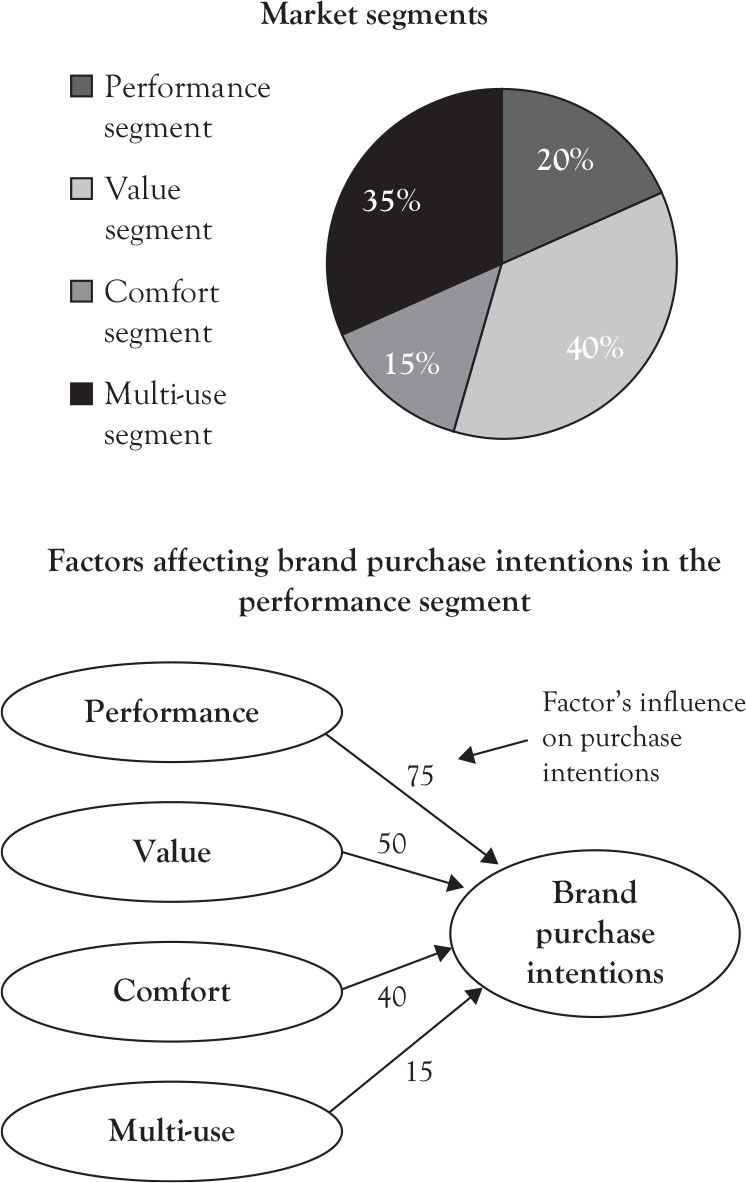

Figure 6.5. Example graphical depiction of a theory.

Figure 6.5 is derived from a formal marketing research study. It defines and depicts the relative size of each of the market segments. Additionally, for the performance segment, it shows factors that influence brand purchase intentions. The relative strength of a factor influencing brand purchase intentions is given by the numbers near the arrows—higher numbers (they range from 0 to 100) denote more influence in affecting purchasing intentions. Generally speaking, the more formally a theory is specified—in both written and graphical form—the better. This is because of the following:

Written and graphically depicted theories force marketers to:

• Think through the theory’s purpose: “Are there segments in the pontoon boat market and, if so, do any of those segments represent opportunities for the company?”

• Specify a formal model supporting what the theory should explain: The molecule diagram with arrows pointing from the factors to the brand purchase intentions construct is an example of a “model.”

• Clarify terms: “How do you define the segments and the constructs that influence consumer behavior within each segment?”

• State how the model will be tested empirically: Ideally, and if budgets allow, theories should be tested empirically so that the beliefs out of which theories are built are indeed justified.

• Document beliefs so they can be challenged, debated, and, ultimately, improved.

Testing

We are able to learn how valid our theories are and gain insights in how to improve them through empirical testing. Because this is not a marketing research textbook, I am not going to delve much into this topic, other than to say that organizations should do some amount of marketing research to validate their marketing strategies, especially those that require significant investment and when the cost of a marketing misfire is high. Several of the business examples cited earlier in this book—especially Brunswick’s acquisition of Sea Pro and the demise of Border’s book stores—are examples in which some proper amount of marketing research could have saved a company millions of dollars as well as its very existence.

Brainstorming and Critical Reflection

These activities apply both to formal (written) and to tacit (unwritten) theories. We all possess a general idea of what brainstorming is, but critical reflection requires some elaboration. Critical reflection is the process of analyzing, reconsidering and questioning experiences within a broad context of issues.15 It consists of the following activities:

• Assumption analysis: Questioning beliefs that support marketing decisions. To what extent, for example, are your beliefs supported by facts or coherent with generally accepted and successful theories in marketing?

• Contextual awareness: Recognizing the fact that our beliefs, in part, arise from our past experiences (and perhaps past mentors), which may result in our holding false beliefs. If you have worked for several different firms, for instance, you likely have noticed how different philosophies of doing business affect how managers approach marketing issues. They cannot all be right!

• Imaginative speculation: Imagining new and novel ways of thinking about marketing phenomenon in order to challenge our beliefs and historical ways of attacking marketing problems. Reading this book is likely challenging how you have thought about and approached marketing problems in the past.

• Reflective skepticism: Playing the devil’s advocate by challenging your accepted beliefs and exploring new ways of viewing marketing.16

The above discussion provides you an introduction to Figure 6.1. Now you are ready to launch in to Chapter 7: Thinking Scientifically: Attributes Versus Constructs.