What I cannot see is infinitely more important than what I can see.

—Duane Michals, Real Dreams

To generate more sales and profits, managers often want to know what new attributes they can add or what existing attributes they can change or modify on a product—except perhaps reducing a product’s price. Rarely, is there such a single attribute. For example, I worked with an international office furniture manufacturer to develop a new office cubicle design that promotes a more productive and comfortable working environment. You can imagine that this task is complex because creating a cubicle that delivers a “comfortable working environment” is a multidimensional undertaking. It requires the development of many different cubicle characteristics relating to the design of items such as cubicle lighting, color, the length, and depth of a cubicle’s work area, the shape and “feel” of cabinet door handles, and so on. In short, the idea of a “comfortable working environment,” is something that is both real and at the same time, intangible. As you will read below, the intangible aspects of a product are often more critical than a product’s individual tangible features in motivating consumers to purchase your product. We call these intangible aspects of a product perceptual constructs.

Perceptual Constructs of Products

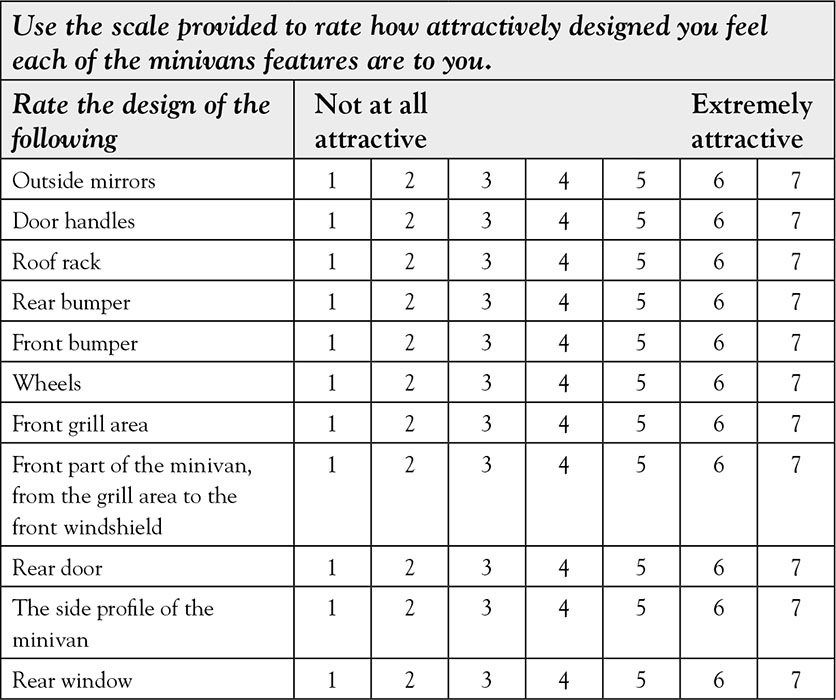

Assume two vehicle manufacturers, manufacturers A and B, believe that the visual appeal of their minivans will influence consumer purchasing behavior. They separately conduct identical marketing research studies in which prospective buyers are recruited to a central facility, shown the manufacturer’s minivan, and rate the vehicle on a set of attributes that describe its physical appearance. Assume these consumers use the hypothetical questionnaire in Table 7.1.

Table 7.1. Hypothetical (Partial) Questionnaire Examining Minivan Attractiveness

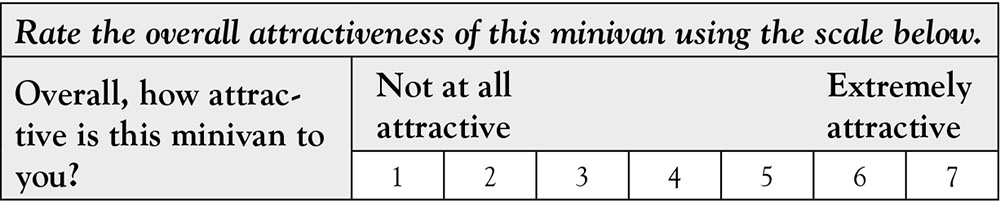

In addition to the physical appearance attributes in Table 7.1, respondents also rate the vehicles’ overall attractiveness using the scale in Table 7.2.

Table 7.2. Overall Attractiveness Rating Example

Assume respondents rate the two minivans similarly. Both minivans receive their lowest ratings on the four items listed below.

Design of the following:

• Outside mirrors.

• Front bumper.

• Front grill area.

• The side profile of the minivan.

Additionally, these attributes are predictive of the “overall attractiveness” rating, which means that if you know how respondents rate a minivan on these four attributes, you can closely predict how they will rate the minivan on “overall attractiveness.” These, then, are the design issues the two manufacturers need to focus on to make their minivans more visually appealing.

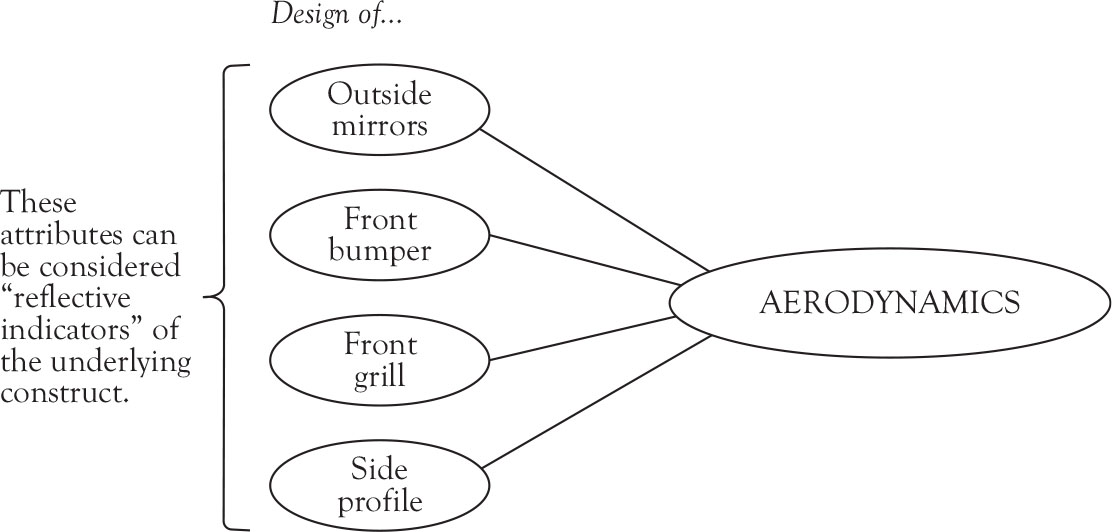

The two manufacturers approach this design goal differently and end up with different outcomes. Manufacturer A instructs its designers to restyle each of these four physical features of the minivan to be more attractive. In contrast, manufacturer B examines these ratings in greater detail, and asks the following question: “Are these four physical features related to some other, more fundamental dimension of how consumers’ perceive minivans?” Manufacturer B answers, “Yes—they are related to a minivan’s overall aerodynamic styling.” Consequently, manufacturer B redesigns the entire vehicle to give its design a more attractive aerodynamic appeal. From this perspective, manufacturer B changes more than just the four physical features described above. They also remodel other vehicle characteristics such as the placement and shape of the windshield wipers, how the front hood aligns with the windshield, and the contours of the minivan’s side panels.

The aerodynamic styling dimension of the minivan goes by several different names—perceptual dimension,1 construct, or factor.2 For purposes of our discussion, we will call ideas such as “aerodynamic styling” (or an office cubicle’s “comfortable working environment”) a construct. A construct reflects a mental state that is not observable, in contrast to a product attribute, which is. We can see, touch, and feel a door handle. We cannot see, touch, and feel “aerodynamic styling.” More specifically, a construct

“…is literally something that scientists ‘construct’ (put together from their own imaginations) and which does not exist as an observable dimension of [a product or] behavior.”3

If a construct describes how consumers perceive an object (e.g., a product, service, or company), we will call those perceptual constructs. See Figure 7.1.

Figure 7.1. The relationship between minivan “attributes,” and the “aerodynamics” construct.

Focusing on this more fundamental dimension of how consumers’ perceive a minivan, manufacturer B changes the research perspective from a focus on symptoms to a focus on the cure. Manufacturer B changes the vehicle’s aerodynamic styling, whereas manufacturer A only changes four of the vehicle’s features. Manufacturer B, of course, sells more cars. The idea of a construct also applies to intangible services as well as psychological constructs that describe individuals.

Perceptual Constructs of Services

Early in my career as a marketing research consultant, my company was heavily involved in financial services research. One observation that kept cropping up in the research projects we conducted for banks, credit card companies, and insurance companies surrounded the concept of service. We discovered that service is not a one-dimensional “construct.” For example, when I talked to a bank’s retail customers about what they liked or did not like about their bank, they talked about bank tellers and the bank in general. Sample topics related to the bank’s tellers were:4

1. Tellers greet me with a smile.

2. Tellers are patient with me.

3. Tellers call me by name.

4. Tellers treat me like a person not a number.

5. Tellers look up to me when speaking to me.

Sample topics they related about the bank were:

6. Continually look for better ways to serve me.

7. Keep me informed about new services.

8. Offer new ideas to help me financially.

9. Provide excellent financial advice.

10. Follow up to see if I’m satisfied with their products and services.

Perhaps you see a difference in these two groups of service attributes. The first group (#1–5) deals with what is called reactive service, which reflects a bank reacting to a customer-initiated action (e.g., walking into the bank or arriving at the drive-through). The second group (#6–10) is called proactive service, which refers to a bank taking the initiative to deliver a valued service to a customer (e.g., sending out notices announcing new products). Therefore, the 10 attributes listed above are, in reality, “reflective indicators” of two perceptual constructs of a bank’s service—reactive and proactive service.

Psychological Constructs

In contrast to perceptual constructs, sometimes we are interested in understanding what kinds of personal, internal goals motivate consumer purchasing behavior. We call these psychological constructs. For example, in psychology, the psychological construct “extrovert” is a label we apply to a person who demonstrates the following behavioral attributes: “talks to strangers, seeks out the company of others, organizes social gatherings, and acts like the life of the party even though he or she sometimes enjoys solitude.”5

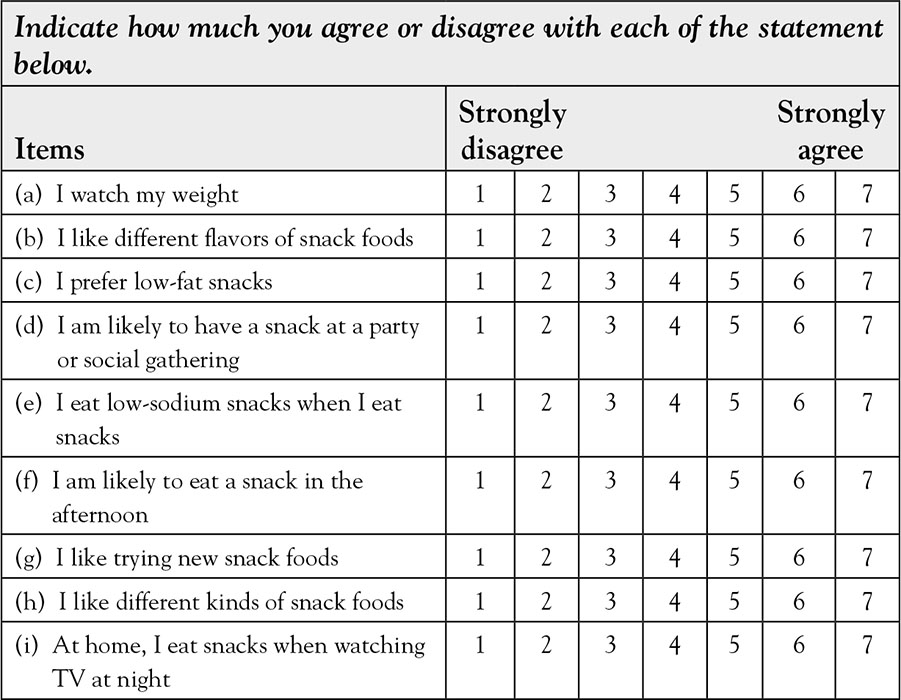

In marketing, market segmentation studies sometimes are built around psychological constructs. For instance, assume we are conducting a segmentation study for a snack manufacturer. A sample set of questions we have respondents answer might be as follows:

Table 7.3. Sample Consumer Snacking Attributes

Once data are collected, a marketing researcher will use one or more statistical methods to identify groups or “segments” of respondents based on how they rate the survey items. The end goal is to create consumer or “market” segments in which respondents’ ratings of the survey items within a segment are relatively homogeneous, but the average ratings of the items among respondents in a segment differ across segments.

In our example, we might find two segments and label them the Healthy Snack and the Variety Seeking segments. On average, respondents in the Healthy Snack segment rate items (a), (c), and (e) relatively high, but rate items (b), (g), and (h) relatively low. Conversely, respondents in the Variety Seeking segment rate (a), (c), and (e) relatively low, but rate (b), (g), and (h) relatively high. See Table 7.4.

Table 7.4. Relationship Among Segments, Constructs, and Attributes

|

Questionnaire items |

Average item ratings by segment |

|

|

Healthy snack |

Variety seeking |

|

|

(a) I watch my weight |

6.3 |

2.1 |

|

(c) I prefer low fat snacks |

6.8 |

5.1 |

|

(e) I eat low salty snacks, when I eat snacks |

6.2 |

3.8 |

|

(b) I like different flavors of snack foods |

4.6 |

6.7 |

|

(g) I like trying new snack foods |

5.1 |

6.6 |

|

(h) I like different kinds of snack foods |

3.9 |

6.8 |

The questionnaire items in Table 7.4 can be considered reflective indicators of two constructs that define these segments: items (a), (c), and (e) reflect the Healthy Snack construct; and items (b), (g), and (h) reflect the Variety Seeking construct. These constructs, then, can guide marketing strategy and product development. For example, in marketing to the Healthy Snack segment, manufacturers today have created many low-calorie-package snacks such as Frito-Lays’ Cheetos® Asteroids® 100 Calorie Mini Bites Cheese Flavored Snacks, and have special sections on their websites that address health issues and snacking. Had manufacturers developed strategies focused only on the three attributes reflecting the Healthy construct, they likely would have only offered lower fat/sodium snacks in traditional package sizes. By focusing on the Healthy Snack construct, manufacturers have not only expanded the number of “healthier” products you find on grocers’ shelves today, but they have developed new package sizes (e.g., 100-calorie packages), and created snack-health information resources consumer can look up on the Internet.

Lessons

Here is how you should think about attributes and constructs when making marketing decisions:

• Focus marketing decision making on constructs versus product attributes. This generally pays greater dividends than constructing strategies around single attributes of products or consumers.6

• Recognize that consumers do not always separate “attributes” from constructs when explaining why they purchase one brand over another. “Construct” is a term used by marketers, not consumers!

• From this perspective, you must play the role of a social scientist when interpreting what consumers tell you about their behavior versus how they actually behave. For a variety of reasons, people cannot always describe what motivates them to do what they do or don’t do. Back in the 1980s when I was conducting financial services research, no respondent ever talked about “proactive service;” but they certainly were drawn to financial institutions that excelled on that “construct.”

Construct-based Strategies

Generally, focusing on constructs provides a greater understanding of consumer behavior than attempting to decipher the mysteries of what consumers do (or do not do) based on examining particular product or consumer attributes. Thus, manufacturer B sells more minivans because it focused its redesign on the aerodynamic perceptual construct. A bank that develops its unique selling proposition on the proactive service construct will be more successful than a bank that keeps its customers informed, but ignores other aspects of proactive service such as offering excellent financial advice. Consequently, there is a widely accepted consensus in the field of marketing that there exists (italic added):

… several hypothetical constructs [important] in [understanding] buyer behavior. These include the constructs of brand and store loyalty, behavioral intentions or buyer plans, predispositions toward choice alternatives, and perceptual biases in selective exposure and processing of information, just to name a few. In addition, there seems to be a basic understanding that individual differences in buyer behavior are likely to be determined by constructs such as the life cycle, lifestyle, socioeconomic status, and role orientation differences among consumers.7

Epistemic Tip

We can relate the idea of “attributes” and “constructs” to one of the most profound and transforming metamorphoses in the philosophy of science: the incorporation of “unobservables” in scientific and social scientific theories. The general consensus of science today is that most (if not all, actually) of the natural phenomena we observe—“observables”—can only be explained by what we cannot observe—“unobservables.” For example, consider how the following unobservables give rise to the observable reality we experience:

|

These unobservable entities… |

...give rise to the observable reality we experience |

|

Viruses |

Colds |

|

DNA |

Hair color |

|

Tectonic plates |

Mountains, earthquakes |

|

Molecules |

Chemical reactions |

|

Spacetime |

Gravity |

|

Interactions between light and proteins |

Green leaves |

|

Attitudes |

Consumer behavior |

Evidence for such unobservable entities and structures—and their significance in helping us understand reality—has been accumulating since the 1600s. Among the first discoveries was Johannes Kepler’s (1571–1630) detection of planets’ unobservable elliptical orbits about the Sun. Today, the unobservable quest continues in all scientific fields, the most popular perhaps being physics, with its high-energy particle accelerators that have partially lifted the shroud hiding the existence of subatomic particles.

Science’s recognition of the role that unobservables play in enhancing our understanding of reality has not always been as it is today. In the early part of the twentieth century (c. 1920), a rather influential group called the logical positivists held that knowledge can only be based on logic, mathematics, and that which can be observed and verified empirically (i.e., what was called the “verifiability principle”). Once science crosses the observable/unobservable demarcation, logical positivists thought, it becomes metaphysics. The prevailing view in science and the social sciences changed, in part, because of the exceptional breakthroughs science made when incorporating “unobservables” in their theories, particularly in the fields of physics, biology, and medicine. As I discuss in Chapter 12, the prevailing philosophical view is that “something like” the unobservable entities in our successful theories—electrons, protons, and consumer attitudes—do indeed exist, a proposition that the logical positivists rejected.

The significance of unobservables to marketing is the role consumer perceptions and attitudes (i.e., unobservable mental states of consumers) play in understanding consumer behavior. Consequently, analyzing sales databases without insight into the unobservable perceptions and attitudes that, in part, give rise to those sales data, is a throw-back to the now discredited logical positivist movement of the early twentieth century.

Difficulty in Articulating Constructs

Consumers cannot always describe a perceptual or psychological construct that influences their purchasing behavior.8 I never had financial services consumers talk to me about their bank’s proactive service until the mid-2000s, when some financial institutions began using the word “proactive” in their marketing communications. Perhaps a major reason for this is related to the fact that when we imagine a product in our minds, we envision that product’s properties (shape, color, size) and not the object independent of its properties. In fact, it is impossible to envision a product without imagining one or more of its properties. The same is true of a service. When you envision a service such as a dry cleaner, you may imagine aspects or “properties” of “consuming” this service such as the feel and appearance of freshly starched shirts.

This idea that consumers have difficulty describing their basic needs and wants has been discussed at length in the marketing literature. For example, Andrew D. Cutler, principal at Integrated Marketing Associates LLC, a Bryn Mawr, PA-based research firm, states:

The difficulty of gaining this insight, however, becomes apparent when you consider that, as human beings, we don’t always have access to our own cognitive processes. We may recognize our likes and dislikes; however, we may only grasp the reasons behind these on a superficial level. The deeper motives that drive our thoughts and feelings can be, and often are, hidden from our own awareness.9

Steven Pinker, director of the Center for Cognitive Neuroscience at MIT, suggests that thought is not dependent on words:

Is thought dependent on words? ... The idea that thought is the same thing as language is an example of what can be called a conventional absurdity … there is no scientific evidence that languages dramatically shape their speakers’ way of thinking.10

Building on Pinker’s work, Gerald Zaltman, Harvard’s Joseph C. Wilson professor of business administration, states that because thought is not dependent on words, aspects of thoughts can be lost in translation when put into words (italic added):

Thoughts typically occur as nonverbal images even though they are often expressed verbally. Thus, the way in which thoughts occur may be very different from the way in which they are communicated.11

Even if it were possible for consumers to describe their most basic needs, wants, or perceptions of products to you (i.e., perceptual or psychological constructs that influence behavior), they may not be truthful, because people sometimes feel compelled to provide a socially acceptable answer, an answer that makes them appear rational, or the answer that they think you want.12

This problem (or frustration for you and me as marketers) is especially acute regarding new product research, and trying to learn from consumers the basic needs, wants, and perceptions that may hold the key to a successful product launch. According to Anthony W. Ulwick, founder and CEO of Strategyn Inc.:

Companies ask their customers what they want. Customers offer solutions in the form of products or services [i.e., attributes]. “I’d like a picture or video phone,” they say, or, “I want to buy groceries on-line.” Companies then deliver these tangibles, and customers, very often and much to everyone’s chagrin, just don’t buy …. Customers should not be trusted to come up with solutions; they aren’t expert or informed enough for that part of the innovation process. That’s what your R&D team is for. Rather, customers should be asked only for outcomes—that is, what they want a new product or service to do for them. Maybe they want to feel a closer bond to people when talking on the phone or to spend less time traveling to and from the grocery store. What form the solutions take should be up to you, and you alone.13

Ulwick’s suggestion to ask consumers “what they want a new product or service to do for them” is one way to prompt consumers to get beyond attributes and talk about more basic needs and wants (e.g., constructs) that they seek in products.

Think Like a Social Scientist

Try to apply scientific reasoning when interpreting what customers and prospects tell you about why they purchase or do not purchase your products. Identify the underlying perceptual or psychological constructs that are influencing your consumers’ behaviors. Additionally, apply this scientific reasoning “filter” to what you hear from sales representatives or your marketing channel members (e.g., store managers). Then, when it comes to designing product strategies, do not merely change your “vehicle’s” door handles. Change its aerodynamic styling.14

Chapter Takeaways

1. Rarely is there a one-to-one correspondence between individual product attributes and basic consumer needs.

2. Rather, a group of related product attributes serves to reflect more fundamental product dimensions—what we call “perceptual constructs of products”—that meet basic consumer needs. For example, changing only the design of a drawer handle will not by itself improve the perception that an office cubicle provides a “comfortable working environment.” More product attributes may need to be changed such as the size and shape of the work area, design of storage areas, or the amount of work-area lighting. But before you make significant changes to your product portfolio, you need to understand the perceptual constructs of your products and the basic consumer needs to which they are linked.

3. Just as there are perceptual constructs of products, there are perceptual constructs of services, as we discussed with respect to proactive versus reactive service.

4. Sometimes marketers are interested in understanding what kinds of personal, internal goals motivate consumer purchasing behavior. We call these “psychological constructs,” and they play a role in understanding segments of consumers each of which seeks different bundles of product attributes to meet their needs. This is a growing topic, for example, in retail food where different segments of consumers are seeking different “benefit bundles” such as “gluten free,” “low fat,” and “low sodium” products.

5. Bottom line:

a. Focus marketing decisions on constructs versus product attributes.

b. Realize that consumers have difficulty describing these constructs. “Construct” is a term used by marketers, not consumers.

c. Because of this, you must play the role of a social scientist when talking to consumers about your products to better understand the fundamental perceptual constructs of your products and psychological constructs of consumers that motivate brand choice.