1

Background to the NEC

Procurement strategy

Contract typology

Conventionally, the parameters of time, cost and quality have been assessed in relation to choosing the correct type of contract for individual projects on the following basis:

- time: design and construction duration and certainty of end date

- cost: overall price (fees and construction) and certainty of final account

- quality: specification standards and workmanship on site.

The procurement analysis of the relative importance of time, cost and quality has historically led inexorably to a decision as to whether a traditional, a design and build, or a management procurement route is appropriate. However, such analysis has also long been predicated on the convention that time will be somewhat compromised under traditional procurement routes, quality will be somewhat compromised under design and build procurement routes and cost will be somewhat compromised under management procurement routes. The arguments leading to this convention are well rehearsed and need not be examined in detail here, as their only real relevance in the context of the NEC is that they represent an outmoded and arguably superseded approach to procurement strategy.

A further subset of contract typology is the payment mechanism, which conventionally falls into the following categories:

- lump sum

- remeasurement

- cost reimbursable.

These generic payment mechanisms remain relevant in the context of the NEC, albeit the NEC offers greater sophistication in their implementation than earlier standard form contracts.

It should be noted that no type of standard form contract, including NEC4, offers either a ‘fixed price’ or a ‘guaranteed maximum price’ (GMP) payment mechanism; these being inventions of those who seek to amend standard form contracts, or draft bespoke contracts, to highly polarise risk allocation.

Contract form

Professional drafting bodies historically published standard form contracts based on traditional procurement strategy3 and subsequently responded to analysis of the so-called ‘time/cost/quality’ triangle by publishing additional design and build and management versions of their standard forms. Architects have long been used to providing clients with procurement advice and indeed are expected to advise on both a ‘Project roles table’ and a ‘Contractual tree’ at a relatively early stage in a project.4 This important advisory role should take account of the need for flexibility and further review.5

Project-specific strategies

Increasingly, a need has developed for contracts to respond to individual project requirements in a more finely calibrated manner; project sponsors simply can no longer accept that only ‘two-and-a-half’ out of the three parameters of time, cost and quality are adequately controlled. The resultant requirement for project-specific procurement strategies leads to what might be described as a hybrid procurement route. Such a route inevitably calls for much more flexible contracts than conventional procurement routes and this may partly explain the apparent growth in entirely bespoke construction contracts being drafted for important projects.

There is arguably a fourth procurement parameter that most 21st-century construction projects are required to take into account and that is risk. NEC4 sets out to offer a highly flexible format which responds to the ‘prototype’ nature of many construction projects and provides the ability to build up an appropriate contract. NEC4 enables a breakaway from conventional procurement analysis and there is no necessary compromise between time, cost, quality or risk management.

Genesis and philosophy of the NEC

Origins

The genesis of the NEC6 was an initiative in the mid-1980s by a new Legal Affairs Committee within the ICE7 in London. This initiative resulted primarily from a general dissatisfaction with ‘Victorian’ style standard form contracts within the construction industry, which had been conceived of prior to the commonplace requirement for complex multidisciplinary projects and which had become increasingly convoluted, in response to the perception of a ‘high-risk’ and ‘adversarial’ construction industry. The initial strategy for a ‘modern’ contract was developed by a small team led by Dr Martin Barnes,8 and a consultative version of the NEC was published in 1991; this was generally received with such enthusiasm that it was followed by an official first edition in 1993. The NEC received important endorsement in the UK Government/industry Latham Report9 of 1994 and the NEC second edition was published in 1995. The partnering ethos of the NEC contract was further endorsed in the UK Government/industry Egan Report’10 of 1998. A review of the NEC in use and users’ comments was undertaken by its drafting panel, under the auspices of its publishers,11 and the third edition, NEC3, was published in 2005. Following extensive use of NEC3 by an expanding range of users, and a targeted review of those users’ findings in contemporary practice, NEC4 was published in 2017.

Application – what is in a name?

An important factor in the interest generated in the NEC was its applicability to a broad range of ‘engineering’ projects. This was ‘officially’ extended to include all construction projects, following the Latham Report, although the revised title ‘ECC’12, intended to emphasise the range of applicability, never really captured end users’ imaginations and the original name ‘NEC’ largely prevailed. Ironically, the initial interest of architects in the NEC might have been greatly increased, and subsequent interest accelerated, had the title been revised to ‘Engineering and Building Contract’. The answer to ‘what is in a name?’ in this instance seems to be ‘quite a lot’!

There was also a clear intention that the NEC should be conceived as a contract that would be operable globally13 and the drafting is intended to facilitate diversity on a number of levels.

Guiding principles

The NEC approach encompassed the concept that both the legal and the management requirements of a diverse range of ‘modern’ projects could be met in a single document and that the avoidance of ‘legalistic’ language would assist in that aim.

The principles of risk theory and risk management were also important considerations, and an early decision was made that the contracting parties and their representatives should be required to act in a ‘spirit of mutual trust and co-operation’.14

The stated objectives of NEC are flexibility, clarity and simplicity, as well as providing a stimulus to good management. The key objectives in drafting NEC4 include providing a greater stimulus to good management and supporting new approaches to procurement which improve contract management – evolution, not revolution.15 In practice, the NEC approach offers a range of benefits which are key to its success:

- ‘pick-and-mix’ contract conditions, to suit both the Project and the Project Team

- plain English, giving both legal and project management rights and obligations equal status

- real-time project management, with contemporaneous decision-making

- cross-industry application, facilitating multidisciplinary working practices.16

The NEC contract family

The NEC family relationship for architects

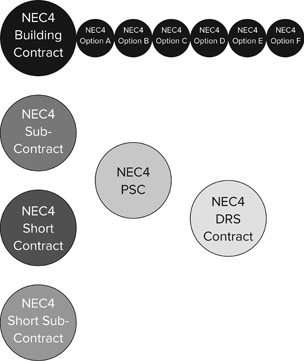

It is pertinent to emphasise that the NEC has been designed for extremely flexible use patterns and different family members will therefore have different levels of significance, depending on the disciplines of users. Architects will tend to be interested in all the family members (see Figure 1); however, they are likely to have the closest relationship with the NEC4 Black Book Engineering and Construction Contract and the NEC4 Engineering and Construction Contract Short Contract in the context of building contracts, and with the NEC4 Orange Book Professional Service Contract in the context of consultants’ appointments.

The NEC4 Subcontract/Short Subcontract will also be significant for architects in the context of specialist design and installation. Historically, architects have tended to take much less notice of subcontract conditions than main contract conditions, often believing the detail of them to be a Contractor’s responsibility and largely outside the sphere of an architect’s influence. Given the decline in staff directly employed by contractors and the greater reliance on specialist subcontractors to realise projects, architects may ignore subcontract conditions at their peril. There have been recent attempts by several drafting bodies to improve coordination between main contracts and subcontracts; nonetheless, NEC contracts have been at the forefront of a coordinated approach since their inception.

Figure 1:

NEC4 ‘Immediate’ Family: building projects

Compatibility, ‘nesting’ of contracts and uniformity

The risk of incompatible rights and obligations as between Client and Contractor within the building contract or as between the Client and Consultants within their professional services contracts is greatly reduced with the provision for back-to-back contractual arrangements. The risk of incompatible obligations as between Contractor and Subcontractor is similarly reduced. The back-to-back drafting has a further benefit, which is that there is no necessary connection between the status of the parties and the type of contract to be entered into, as between construction and professional services.

It is possible to ‘nest’ a number of contracts within each other, irrespective of whether the head contract is for construction or professional services. The conventional approach may be perceived as nesting subcontracts into a construction contract, or in the context of design and build procurement, also nesting professional services contracts into a construction contract. However, the flexibility of the NEC allows not only for the nesting of ‘same’ contracts within each other (e.g. NEC subcontracts or Professional Services Contracts), but also potentially for unconventional nesting such as construction within professional services.

Uniform application of the NEC methodology is encouraged by the publication in parallel with the contract versions of comprehensive User Guides to preparing and managing those contracts, as well as guidance on establishing appropriate procurement and contract strategies. These do not form part of the contract itself, but nevertheless provide valuable assistance in understanding and operating the project management principles of the contract.

NEC4 published contracts

Generally, there has been an attempt with NEC to provide as few separate contracts as possible, preferring the ‘pick-and-mix’ approach, although some separation has proved desirable in the evolution of the NEC family. Such separation remains unrelated to generic choice of procurement strategy as between traditional, design and build, or management, but rather relates to making the ‘nesting’ of contracts flexible and providing a clear interrelationship. All previously published NEC contracts were revised in 2017 as the fourth edition, and some additional contracts have been included in NEC4.

In order of their importance to architects, the NEC4 family comprises of the following publications:

The NEC4 ‘Building’ (Engineering and Construction) Contract

(June 2017)

The so-called ‘Black Book’

Architects could be forgiven for unofficially renaming this the NEC4 ‘building’ contract. It is very important for architects to bear in mind that this single book represents a standard form building contract blueprint, equally appropriate for traditional, design and build, management and hybrid procurements strategies. It is this universality that is of paramount importance in giving architects and their clients real choice, both at the outset of projects and, where necessary, during later stages of the procurement process.

The NEC4 ‘building’ contract is also published individually for each of the six ‘payment mechanism’ main options A to F,17 although this is for convenience, not necessity, and should certainly not be misunderstood, in that it remains a single contract form.

The NEC4 (Engineering and Construction) Short Contract

(June 2017)

(Dark Book)

Building clients may find this version of NEC4 appropriate where the Project is relatively straightforward, without the need for much fine-tuning of the contract conditions18. The Client and the Contractor communicate directly with one another, without a dedicated ‘contract administrator’, although there is provision for ‘delegated authority’ from the Client. Perhaps the most helpful way of deciding whether the NEC4 Short Contract might be appropriate is to consider it to be suitable for low-complexity, rather than low-value, projects. Historically, some standard form drafting bodies have made minor works contracts available and indicated that they are suitable for contracts up to certain, relatively low, monetary values. The critical point with the NEC4 Short Contract is that it may be eminently suitable for high-value contracts, provided that the work content of such contracts is relatively simple.

The NEC4 (Engineering and Construction) Subcontract

(June 2017)

The so-called ‘Purple Book’

It is no exaggeration to state that the only significant difference between the Purple Book19 and the Black Book is simply that the Purple Book refers to the Contractor rather than the Client and to the Subcontractor rather than the Contractor. However, this deceptively simple swap is in turn the key to the success of the NEC4 Subcontract – it is genuinely back-to-back with the main contract Black Book.

The NEC4 (Engineering and Construction) Short Subcontract

(June 2017)

(Mauve Book)

In a mirror of the Purple Book/Black Book relationship, it is also no exaggeration to state that the only significant difference between the NEC4 Short Subcontract and the NEC4 Short Contract is simply that the Short Subcontract refers to the Contractor rather than the Client and to the Subcontractor rather than the Contractor. The Short Subcontract is therefore not only genuinely back-to-back with the Short Contract, but also offers an alternative to the Purple Book for subcontracted works of a simple nature under the Black Book.

The NEC4 Professional Service Contract (PSC)

(June 2017)

The so-called ‘Orange Book’

The PSC is interesting for architects, in that like the Subcontract, it offers the potential for back-to-back contractual arrangements.20 This potential may be particularly relevant where architects are employed initially by Clients and subsequently by Contractors under design and build procurement arrangements, in that there is likely to be much less potential disparity between pre- and post-novation obligations. Another context in which the back-to-back potential is likely to assist architects is where they are involved in projects side-by-side with several other specialist consultants; whether the architects are acting as lead consultant or not, there will be much less risk of gaps and/or overlaps in the totality of the consultants’ work.

The NEC4 Professional Service Short Contract (PSSC)

(June 2017)

(Bright Orange Book)

Architects may find this version of NEC4 appropriate when the professional services requirements are relatively straightforward and where building clients are lay people/consumers rather than professional/repeat clients.

The NEC4 Professional Service Subcontract (PSS)

(June 2017)

(Navy Book)

Architects may find this version of NEC4 appropriate when they are employing subconsultants to carry out professional services. It may also be appropriate for architects to be appointed when they are working for a Contractor to provide professional services under a design and build procurement route. This contract is a new addition to the NEC family with the publication of the fourth edition, NEC4.

The NEC4 Term Service Contract (TSC)

(June 2017)

(Grey Book)

Essentially, the TSC is intended to operate with the same flexibility and control as the Black Book for ongoing works, such as maintenance tasks, which cannot be fully defined from the outset.21

The NEC4 Term Service Short Contract (TSSC)

(June 2017)

(Pale Grey Book)

The TSSC offers a simple methodology for ongoing maintenance type works of a straightforward nature. The Client and the Contractor communicate directly with one another, without a dedicated ‘contract administrator’, although the Contract provides the option of the Client appointing an Employer’s Agent.

The NEC4 Term Service Subcontract (TSS)

(June 2017)

(Ruby Book)

The TSS may be appropriate where a Term Service Contractor wishes to appoint Subcontractors for a period of time.

The NEC4 Design Build and Operate Contract (DBO)

(June 2017)

(Turquoise Book)

The DBO Contract is new to NEC4 and is intended to provide a vehicle specifically suited to clients who wish to appoint a Contractor with responsibility to design, construct and operate assets, whether the construction is new build or refurbishment.

The NEC4 Supply Contract

(June 2017)

(Red Book)

The NEC4 Supply Contract is intended for the purchase (locally or internationally) of high-value goods and related services, which may include design.

The NEC4 Supply Short Contract

(June 2017)

(Puce Book)

The NEC4 Short Supply Contract is intended for the purchase of relatively simple goods.

The NEC4 Dispute Resolution Service Contract (DRS)

(June 2017)

(Green Book)

The adjudicator has had a role under the NEC contract prior to the introduction of statutory adjudication in England and Wales.22 It has always been considered advantageous to treat the adjudicator as a person involved in a project in a potentially positive way from the outset. The corollary to this perspective is that an NEC adjudicator should be signed up from the beginning, and that is the basis upon which the NEC4 Dispute Resolution Service Contract is intended to operate.

The NEC4 Dispute Resolution Service Contract is also the appropriate contract for appointing Dispute Avoidance Board members.

The NEC4 Framework Contract

(June 2017)

(Beige Book)

The NEC4 Framework Contract23 provides a standard umbrella contract for other NEC contracts to be potentially instructed to pre-qualified suppliers24 over a set period. Architects working in the context of public procurement25 may find the NEC4 Framework Contract a valuable member of the NEC contract family, in that it obviates the need for bespoke framework contracts which can often conflict with the standard form terms under them.

Notes

3 Separation of design and construction.

4 RIBA Plan of Work 2013: Work Stage 1.

5 Ibid.: Work Stages 2–4.

6 New Engineering Contract.

7 Institution of Civil Engineers.

8 BSc(Eng) PhD FICE FCIOB FAPM FICES MBCS CCMI FREng CBE.

9 Latham, M. (1994) Constructing the Team, London: HMSO.

10 Egan, J. (1998) Rethinking Construction: Report of the Construction Task Force, London: HMSO.

11 Thomas Telford Publishing, London.

12 Engineering and Construction Contract.

13 See Chapter 5.

14 NEC4 Core Clause 10.2.

15 NEC4 User Guide, June 2017.

16 Envisaged in the Banwell Report, 1964.

17 See Chapter 2, Main option clauses.

18 See Chapter 2, Secondary option clauses.

19 See Chapter 4, Secondary Option X12 and Subcontracting.

20 See Chapter 4, Professional services.

21 See Chapter 4, Secondary Option X12 and Framework agreements.

22 Housing Grants Construction and Regeneration Act (HGCR Act) 1996 brought into force with the Scheme for Construction Contracts (England and Wales) Regulations on 1 May 1998.

23 See Chapter 4, Framework Agreements.

24 Whether Consultants or Contractors.

25 Within the European Union currently.