2

Structure and content of NEC4

‘Pick-and-mix’ assembly of the contract

Clause hierarchy and contract layout

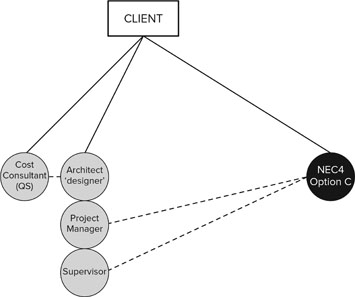

Of paramount importance is the structure of the NEC4 contract conditions as a three-tier shopping list, comprising (1) core clauses, (2) main option clauses, and (3) secondary option clauses, from which the necessary items must be selected. The selection criteria are to be found in the project type and risk profile.

A fundamental drafting decision, which is key to the clarity of the NEC clauses in practice, was to take advantage of starting from the beginning and to arrange the document in a logical order. First, there is a clear group of concepts set out in nine ‘core clause’ sections and, therein, a clear sequence of clauses dealing with the specific nature of each concept. Cross-referencing between clauses is avoided and related elements are kept within the individual sections. The drafting of these core clause sections is genuinely generic, with the clear intention that they are applicable to any project, whatever its nature and wherever it is in the world, under whatever jurisdiction. Second, a single ‘main option’ is chosen to determine the pricing mechanism applicable to a particular project and to add the corresponding clauses required to operate it. Third, an assessment is made as to which, if any, of the ‘secondary option’ clauses will assist in fine-tuning the contract to meet the specific needs of that project. Finally, a decision is made as to which option applies for resolving and avoiding disputes.

Necessary clauses

Many standard form contracts presuppose that all projects follow a similar enough route under a particular procurement strategy for all the contract conditions to be the same, i.e. generic. Even in the context of a clear decision as to the procurement route and therefore the contract form, this is inflexible and tends to favour a ‘form-filling’ mentality rather than a creative approach to assembling the appropriate contract for a certain project. There are parallels for this distinction in other areas of an architect’s expertise, for example, when completing an NBS-style26 specification, one approach would be to leave most standard clauses intact – just in case they prove useful, while the opposite approach would be to start from a blank sheet and only include those clauses which are considered strictly necessary. NEC4 is analogous to the latter approach, which tends to result in shorter documentation, avoidance of extraneous or superfluous clauses and consequential clarity.

‘Designing’ the project-specific contract

While some organisations have deliberately put in place standard contract preparation procedures to maintain quality, it is clearly inadvisable to follow such procedures when assembling the contract conditions of an NEC Contract. The whole point of the three-tier hierarchical structure is that it allows for the contract to be ‘designed’ as a tight fit for the needs of an individual project. It is not only acceptable, but also positively to be expected, that different main option and secondary option combinations will be chosen to augment the core clause sections for different projects. Even where projects are of a similar building type, or for the same client body, the decisions on appropriate options should be made afresh each time, to enable optimum performance of the NEC Contract on any one project.

NEC4 is a proactive contract, requiring hands-on management from the outset, including putting it together. There is no default version of the contract and it simply will not be operable if its assembly does not follow the envisaged structure or is incomplete. NEC4 will appeal greatly in the context of wanting a pragmatic framework within which to manage real projects effectively. The necessary skillset of architects is such that they should be well equipped to respond to the need to assemble the contract creatively, carefully and in adequate consultation with their clients.

Core clauses

There are nine core clause sections, each of which deals with an individual concept.

Figure 3:

NEC4 Core Clauses

The following provides an interpretive commentary on the salient points within those concepts, rather than simply paraphrasing all the clause content.

Core Clause Section 1: General

This general section is key to operating the entire contract, and new users of NEC4 who have perhaps become used to skim-reading older forms of contract (whether because of familiarity or tedium!) would do well to be meticulous in working their way through this section. The drafting style throughout the contract is refreshingly succinct and the meaning and purpose of individual clauses should be relatively easy to discern. Ironically, there is more risk that the succinctness will be interpreted oversimplistically than there is that any clauses will be regarded as obtuse.

The first clause of the contract, Clause 10 Actions, has sometimes been regarded as its most controversial:

- 10.1 The Parties, the Project Manager and the Supervisor shall act as stated in this contract.

- 10.2 The Parties, the Project Manager and the Supervisor act in a spirit of mutual trust and co-operation.

In the early years of NEC, many probably regarded this clause as aspirational, rather than legally binding; now, it is much more likely that a failure to act as required might be construed as a ‘breach of contract’. The statement in Clause 10.2 has come to be seen as virtually synonymous with the ethos of partnering. The progress of partnering has been such that it is no longer fanciful to ascribe legal obligation to that ethos.27 The ethos is also consistent with the concept of ‘good faith’ under civil law jurisdictions, which is a well-established legal obligation in most European countries.28

In view of the NEC provision for use in different jurisdictions, it is important to check the law of the contract, whether in terms of what is appropriate when filling out the Contract Data, or in terms of retrospectively assessing legal obligations.

The explanation of identified29 and defined30 terms is extremely important to correct understanding and usage of all the following clauses, and this part of the contract will become well-thumbed by architects administering NEC4 contracts, whether acting as Project Manager, Supervisor or both.31

NEC4 has an ‘entire agreement’ clause,32 which has the usual purpose of improving clarity by excluding any prior agreements. The Contractor is not expected to do anything illegal or impossible and must not do anything corrupt.33 There is also a ‘prevention’ clause34 which allocates the risk of unforeseeable events to the Client.

Types of communication are specified under NEC4,35 both in terms of type and timescale – this is a critical factor in improving project management.36 It is acknowledged that ambiguities or inconsistencies could exist in the contract documents and provision is made to resolve any such items.37

NEC4 envisages that the Contractor may need access to places that are not part of a building site as such and that there may also be reason to restrict access on a building site to specific areas – the combination of these being defined as the Working Areas.38 This is a more sophisticated approach than simply giving a Contractor ‘possession’ of a site and in practice, allows better control and a manageable solution to any need to share spaces on a building site. There is provision for making additional areas available where this becomes necessary.

NEC4 focuses throughout on efficient project management and contemporaneous resolution of any matters that could affect time, cost or quality.39 The early warning provisions and the maintenance of an Early Warning Register are vital provisions in this respect.40

Core Clause Section 2: The Contractor’s main responsibilities

In Providing the Works,41 the Contractor is only bound by the content of the Scope, which means in practice that the quality of the Scope is of paramount importance in controlling the realisation of any building being constructed under an NEC4 contract.42 Architects would typically be responsible for the production and coordination of the Scope on building projects and will therefore be particularly interested in the relationship between its quality and that of the corresponding completed building.

The Contractor has potential responsibility for design of parts of a building, subject to individual project requirements.43 In practice, those individual project requirements might suggest anywhere between 0% and 100% design by the Contractor, whether the percentage be of the entire building or of discrete constituent parts. The NEC4 Black Book building contract enables architects to have tremendous freedom in deciding exactly the right split in terms of what design work is allocated to whom and at what stage of the Project.44 The Contractor also has potential responsibility for design of Equipment;45 i.e. typically on building projects, temporary works necessary to realise the permanent works. The Scope is the correct place to accurately define any requirements for the Contractor to design any item, whether permanent or temporary. The Scope is also the correct place to identify the parameters of the Client’s rights in relation to using any designs executed by the Contractor.46

The Contractor has responsibilities concerning provision of key staff and any necessary replacement of staff. The Contractor also has potential responsibility to cooperate with Others,47 including sharing the Working Areas. In practice, these responsibilities are extremely useful project management aids, particularly as they recognise the wealth of external bodies and stakeholders who can be involved in today’s building projects.

The Contractor has potentially onerous responsibilities concerning any subcontracting,48 although the correct discharge of those responsibilities reaps significant rewards in terms of efficiency and quality of outcome, which is arguably in both the Contractor’s and the Client’s best interests.

In view of the potential international use of NEC4, the Contractor’s responsibilities in relation to health and safety are not stated in the core clauses but are to be stated in the Scope specific to an individual project. Architects building in the UK need to be aware of this distinction and ensure that appropriate references to relevant legislation49 are made in the project-specific Scope.

Core Clause Section 3: Time

The temporal provisions of NEC4 are prescriptive, challenging and very good news. It is no exaggeration to state that architects have conventionally been in the hot seat in relation to delays on projects and that discharging their responsibilities with respect to extensions of time under many standard form contracts has become exceedingly difficult. It is an area where responsible architects would be justified in suffering sleepless nights, given the potentially disastrous combination of ‘responsibility without authority’ which appears to exist in the drafting of some standard form contracts in relation to assessing responsibility for delay. The nub of the issue is that if an architect is expected to make such assessments objectively and in accordance with the critical temporal path of a project,50 then doing so without the benefit of an appropriate programme from the Contractor is well nigh impossible; producing such a programme independently, while possibly sensible if shown to the contracting parties, is nevertheless illogical.

Where NEC4 differs radically from many other standard form contracts is in its approach to the provision by the Contractor of a programme which can be seen to assist everyone involved in a project in achieving clarity and certainty of temporal outcome, both from the outset and as the Project progresses.51 The status of that programme, once initially accepted and subsequently reaccepted by the Project Manager,52 is binding on both parties to an NEC4 building contract, i.e. Client and Contractor alike.

NEC4 distinguishes between the starting date and the first access date, thus catering for the eventuality of early Contractor involvement, prior to commencement of construction on site.

The conventional distinction between a contractual completion date and the actual date of completion is made in NEC4 as well, the former being stated in the Contract Data and the latter being certified by the Project Manager.

NEC4 provides for Key Dates, which in practice can be very helpful on some relatively complex building projects where a Client may need to ensure critical dates along the way are controllable, without necessarily requiring Sectional Completion.53

A novel feature for architects to find in a standard form contract is the ability in NEC4 to propose acceleration.54 This provision should not be used lightly and clearly has potential financial implications; however, there will be building clients and building projects where there would be undoubted benefit in the ability to suggest ‘official’ acceleration to achieve earlier completion of a project, or part of a project, and to formalise this if the Contractor agrees.

Core Clause Section 3 is one of the most fundamentally different concepts relative to other standard form building contracts; it is also one of the most rewarding sections of NEC4 for architects to get to grips with.55

Core Clause Section 4: Quality management

The role of the Supervisor will be new to architects using NEC4 for the first time.56 The responsibilities in relation to quality are not merely advisory, as is often the case with a ‘clerk of works’ role; they are an integral part of the overall contract administration to be carried out on behalf of the Client.

The multidisciplinary nature of NEC4 is such that foreseen testing and inspection of specific items is envisaged as a potential project requirement and this is provided for on the basis that it applies to any parts of a project so designated in the Scope.57 Historically, some building projects have not had any requirement for foreseen testing or inspection; nevertheless, there are now many contexts where the clear contractual provision will benefit projects (e.g. concrete cube testing for crushing strength, visual inspection of full scale mock-ups of facade materials, air-tightness testing for building regulations compliance, etc.). It is important at design stage that architects give appropriate thought to necessary inspection of samples and testing requirements, in order that appropriate specification can be incorporated into the Scope.

Core Clause Section 4 also covers dealing with unforeseen testing and inspection, i.e. checking for defects. There are reciprocal obligations as between the Supervisor and the Contractor to notify each other of each defect as soon as they find it.58

Core Clause Section 5: Payment

The operation in practice for the payment provisions within NEC4 will depend heavily on which main option is chosen. The primary reason for this is that both the definition of Defined Cost59 and the definition of the Price for Work Done to Date (PWDD)60 are different for each main option, as is to be expected in the context of each main option allowing a different payment mechanism. Architects initially observing projects under the NEC4 form of contract may find it helpful to look at the main option payment provisions simultaneously with the core clause payment provisions – this is essential for any architect acting as Project Manager and therefore administering those payment provisions! It is also important to realise that the payment provisions under each of the main options rely on the proper execution of the relevant parts of the Contract Data in order to become fully operable. It is exceedingly rare under NEC4 for payment difficulties to arise if the contract has been assembled properly; however, if there has been any lack of rigour in doing so, it is fairly predictable that severe difficulties and unexpected outcomes can arise.

Architects should take particular note of the requirement to account for applicable tax, in addition to substantive sums, in amounts due for payment, as this is not usual in other standard form building contracts. Architects should also note, where applicable, the requirement to account for interest in the case of any corrections to substantive sums.

There is a deliberately draconian provision in the payment section which effectively withholds 25% of the amount to be paid to the Contractor until such time as a first programme is submitted by the Contractor.61 This is intended to severely disincentivise the Contractor from failing to fulfil the programme requirements in Core Clause Section 3 (Time),62 because such failure would in turn make other provisions within the contract, notably the compensation event provisions, inoperable.63

Core Clause Section 6: Compensation events

This section is regarded by many as the magnum opus of the NEC core clauses. Section 6 is certainly a section that received many comments in relation to earlier editions of NEC and it was probably the most amended section between the second and third editions of NEC.

Essentially, the compensation event procedures in Core Clause Section 6 of NEC4 are intended to deal simultaneously with both the financial and the temporal consequences of foreseeable events which materialise during the course of the contract and which are at the Client’s risk.

The whole idea of ‘compensation events’ is pivotal to the successful operation of NEC. In the context of risk management, it is important to acknowledge that all risks which materialise on a project are allocatable to one or other party to the contract for that project. The well-rehearsed, albeit somewhat glib, risk management advice that residual contractual risk should be allocated to the party best able to carry it is completely compatible with the concept of compensation events. The contractual list of compensation events,64 while specific and exhaustive, is a powerful tool in appropriate risk allocation and risk management on an individual project. Anyone questioning how a prescriptive, generic list of compensation events can be flexible enough to manage a plethora of varying risk profiles on different projects would be missing a key feature of NEC4: i.e. the author of the Scope is in virtually complete control of the Project’s destiny! Notifying, assessing and implementing compensation events all take place relative to that project-specific Scope and the Accepted Programme and outcomes will therefore be as variable as the risk profiles and Scope and Accepted Programme content for individual projects.

By inextricably linking time with money and by relating both to objective contract documents, i.e. the Scope and the Accepted Programme, it is possible through correct operation of Core Clause Section 6 to maintain throughout any project contract both a running final account and a predicted date for completion, both of which will normally65 be a maximum of three weeks behind real time.

Core Clause Section 7: Title

On most projects, Core Clause Section 7 probably attracts the least attention of all the core clause sections; certainly its content and brevity indicate that architects can distil the salient points relatively quickly.

The concept of Working Areas is helpful to architects in giving clarity over ownership of, and right to payment for, materials intended to be included in the works,66 which are not yet on the actual building site. Conversely, there should be no question of the Contractor expecting payment for any materials stored outside the Working Areas, unless the NEC4 contract has been executed to include Advanced Payment.67

This section also ensures that the Client is not left with unwanted temporary items at the end of the Project68 and that there is clarity over items found within the site during construction.69

Core Clause Section 8: Liabilities and insurance

The respective generic risk allocation as between the Client and the Contractor is set out in this section.70 This should be distinguished from the project-specific risk allocation which is largely defined by the content of the Scope.

The default is that generic liabilities are required to be covered by insurance and that insurance is taken out by the Contractor in joint names, unless the Contract Data specifically gives any insurance obligations to the Client. There is an insurance table71 summarising the type of cover required, which falls into the four categories of: (1) works insurance, (2) equipment (temporary works/machinery) insurance, (3) public liability (persons and property) insurance, and (4) employer liability insurance. The Contract Data is the correct place to identify any swap of insurance obligations from Contractor to Client, as well as any additional insurance requirements, for example, professional indemnity insurance.

Given the potential for NEC4 to be used in different countries and jurisdictions, there is a need to ensure that both types and levels of insurance cover are in accordance with the applicable national law and that the Contract Data is filled out accordingly.

There is a reciprocal requirement for whichever party is responsible for taking out the insurances to submit insurance certificates and/or policies to the other party for acceptance.72 There is also a reciprocal right for a party to counter-charge the other party for having to take out insurance in the absence of proof from that other party, if they are responsible for taking out such insurance, that the required policy is in place.73

Core Clause Section 9: Termination

This is perhaps the least easy core clause section to digest, in that it sets out specific rules to be followed in the event of termination by either the Contractor or the Client. These rules are relatively complex, and the only consolation is that this entire core clause section will be relatively rarely used.

Either party may terminate for the reasons74 set out in the Termination Table,75 which correlates the procedures to be followed76 and the payment amounts due on such termination.77

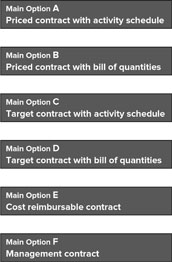

Main option clauses

There are six main options, a single one of which must be chosen in order to provide a payment mechanism and make an NEC4 contract operable.

Figure 4:

NEC4 Main Option Clauses

It has sometimes been questioned whether NEC contracts are fairer, i.e. have a better balanced allocation of risk, than other standard form contracts. The only correct answer to such a question is that ‘it depends’. One of the key things it depends upon is a rational choice of the contractual payment mechanism, that is, the one, and one only, main option. Risk allocation can be significantly altered on the same project by virtue of the choice of main option. New users of NEC4 should not treat the main options as a pick and mix where they necessarily have to try all the flavours! It is entirely to be expected that professionals and their clients working predominantly in one sector of the construction industry will not go through the whole array of NEC4 main options. Architects working not only on building projects, but also possibly specialising in a certain building type with a specific client base, may choose to use the same main option on numerous projects. This is most certainly not because NEC4 should be ‘standardised’ in a practice, but because it is foreseeable that when proper procurement analysis takes place on each project, and each project has similarities, then it follows that the same NEC4 main option may consistently provide the best contractual fit for a particular project.

In summary, the choice of main option is crucial to the successful operation of an NEC4 contract. Architects should keep an open mind in analysing the right choice for any one project but should not be tempted to choose a different main option ‘just for a change’.

Main Option A: Priced contract with activity schedule

Main Option A essentially creates a lump sum contract, suitable for a range of building projects. Most architects experienced in administering other standard form contracts on a traditional procurement route will probably find Option A the easiest to relate to; however, NEC4 Option A is not restricted to traditional procurement. After carrying out a full analysis of procurement strategy for a particular building project, architects should not be concerned if they regularly decide that Option A is the most appropriate NEC4 main option to put forward to their client.

The payment mechanism under Main Option A is incredibly straightforward, in that the Contractor is entitled to be paid for each completed activity. It is important to realise the significance of activities having to be complete. First, complete does not mean nearly finished, it means 100% finished; the Contractor is thus incentivised to stay on programme. Second, there is no need for either debate or specific ‘valuation’ expertise in order to determine the value of a completed activity; it will simply be the monetary value ascribed to the relevant activity within the Contractor’s Activity Schedule. This is why quantity surveyors need not perform a conventional valuation role in relation to NEC4 Option A contracts.

Those who remain unfamiliar with activity schedules under any standard form building contract sometimes question why an NEC4 activity has to be 100% complete. The answer is simply that there is no mechanism for assessing the value of partially completed activities. While it might be very easy and relatively accurate to pro-rate, for example, five courses of a 10m length of blockwork which is to be 15 courses high and the same length when complete, it would clearly be much more difficult to pro-rate, for example, a partially completed mechanical or electrical services installation. The benefits of allowing a Contractor to split up a project into activities relating to appropriate work elements, in relation to both logical progress on site and cashflow, would be completely lost if the Client still had to ensure that some sort of pricing document be produced in tandem, solely to enable partially completed work elements to be valued. Indeed, there would be significant scope for disputes to arise due to potentially conflicting methods for assessment of value.

If difficulties do arise with NEC4 Option A, it is likely to be due to a lack of understanding of the principles of activity schedules per se, rather than the requirements of NEC4. It is perhaps significant that while a number of standard form contracts have offered activity schedules as an alternative payment mechanism for some time, there is relatively little anecdotal evidence of their use in the building sector of the construction industry, and perhaps even less evidence of their success where occasionally used under other standard form building contracts.

It may be helpful to consider some particular criteria which contractors should give due regard to when splitting up a project to prepare an activity schedule:

- Does the Activity Schedule cover the entire works? That is, does there need to be a catch-all activity for ‘everything else’ other than the listed activities, or can the list of activities be exhaustive? ‘Missing’ activities could clearly lead to difficulties over entitlement to payment.

- Upon what basis does a project lend itself to be split up? For example, trade-related elements, demarcated geographical areas on the site, etc. In practice, this will depend on the size and nature of the particular project; many projects may benefit from being split up on a two- or three-tier basis. There is no magic right number of activities on any project; too few activities could lead to cashflow difficulties and too many could become an administrative burden. It may be advantageous to management clarity to group activities which are interdependent.

- What is the relationship between physical activities and management activities? That is, are there benefits in separating them or are they inextricably linked?

- Items which are conventionally priced under the heading of ‘Preliminaries’ are still activities and should appear in an activity schedule accordingly. This is essential under the NEC4 form of contract because of the NEC principle of inextricably linking time with money.

- Are the individual physical activities logically related to technical requirements in executing the works on site? For instance, if a concrete pour has to be done in two stages because of temporary works obstructions, then it should clearly also comprise of two separate activities.

- Have the durations of activities been considered in relation to contractual payment intervals? For example, if all the substructure concrete is to be poured sequentially, but that sequence will last for five weeks and the payment interval is four weeks, then it will assist cashflow if that physical sequence is split into two activities.

It is sometimes questioned how the NEC4 Option A provisions should work in the case of a Contractor realising either that an activity cannot be completed as a discrete element of work, or that they wish to change their methodology for an activity. It is also often questioned how the NEC4 Option A provisions should work in the case of a change to the required work under the Contract affecting one or more activities. The key to answering these points is to understand the relationship between the Activity Schedule and the Accepted Programme.

In the case of the Contractor wishing to change the sequence of work on site, they are entitled to do so, but they must alter the Activity Schedule and resubmit it, if necessary with a correspondingly revised programme.78

In the case of an instruction to change the works required under the contract (the Scope), the Contractor is obliged to change the Activity Schedule accordingly.79

For routine payments as a project progresses, Main Option A simply requires the Project Manager, possibly with assistance, to be capable of assessing whether any activity is 100% complete and should therefore be included in the certified sum for payment. In practice, any architect who has been involved in the preparation and coordination of the design documentation and who has studied the Contractor’s Activity Schedule should have no difficulty in deciding when an activity is 100% complete.

In addition to routine payments, the Main Option A payment mechanism also has to deal with payments that may become due as a result of instructed changes under the contract. Main Option A provides for a fee to be applied in the case of compensation events, that fee being a percentage which is applied to the Defined Cost of the work.80

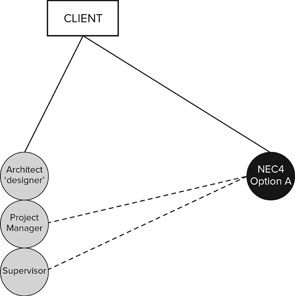

Figure 5:

NEC4 Main Option A: Architect Acts as PM and Supervisor

Main Option B: Priced contract with bill of quantities

Main Option B effectively creates a remeasurement contract because of the minimal inaccuracy margin permissible in the Bill of Quantities, without it becoming grounds for a compensation event. If architects are putting Main Option B forward to their clients as the most appropriate payment mechanism for a project, they should emphasise that it does not create a lump sum contract and that the potential risk for quantity changes would rest with the Client.81

This main option is possibly the one which many architects who are experienced in administering other standard form contracts on a traditional procurement route will tend to gravitate towards, if only because of the familiarity of the terminology ‘Priced Contract with Bill of Quantities’. In practice, this could cause difficulties for architects and their clients alike, unless there is complete clarity over the issue of remeasurement, i.e. complete understanding and acceptance of the fact that because Main Option B does not automatically create a lump sum contract, even if no changes were instructed, the price would not necessarily remain fixed.

This is not a defect in NEC4, but rather a natural consequence of the NEC principle of flexibility and its design as a contract which caters for a potentially vast range of project requirements. Any architects who have worked on multidisciplinary projects such as rail infrastructure are likely to have come across the custom of remeasuring engineering quantities. Equally, architects who have worked on refurbishment projects are likely to be familiar with standard form building contracts that are either ‘without quantities’, or ‘with approximate quantities’, i.e. contracts that assume measurement, or remeasurement, of quantities.

Main Option B envisages conventional preparation of a Bill of Quantities on behalf of the Client at tender stage and it foresees the possibility that individual lump sums may be allocated to specific items which are included in the scope of work to be carried out by the Contractor. Option B provides a payment mechanism where the Contractor is entitled to be paid for each item in the Bill of Quantities on the basis of quantity multiplied by the rate and is entitled to be paid for lump sums. This accounts for why clients will normally retain quantity surveyors or cost consultants in relation to NEC4 Option B contracts, both for preparation of the Bill of Quantities pre-contract and to perform a ‘valuation’ role post-contract.

One of the critical differences between NEC4 Main Options A and B in the context of building projects is that the fees for preparation of the Option B Bill of Quantities will be borne directly by clients and the pre-contract programme will have to allow adequate time for its preparation, whereas the Option A Activity Schedule will be funded by tendering contractors as part of their bidding risk. While Option A tender periods should reflect the Activity Schedule production time, this is unlikely to increase the length of a pre-contract programme by as much as the Option B Bill production.

One slight philosophical anomaly between Main Option B and Option A is in the context of any individually allocated lump sums under Option B relative to activities under Option A. The Option B payment mechanism allows for proportional payment for lump sums on the basis of proportional completion of each lump sum. This is in direct contrast to the Main Option A payment mechanism of avoiding proportional payment and only allowing payment of 100% complete activities. Main Option B does not, therefore, assist in incentivising the Contractor to stay on programme in the way that Option A does. It is also foreseeable that a dispute could potentially arise under Main Option B about the precise proportion of a lump sum which had been completed at the end of a particular payment interval. While it is consistent with the whole principle of a Bill of Quantities that proportional payment takes place, it is tempting to conclude that Main Option B is much less radical than Option A in its approach to incentivisation and dispute avoidance techniques. To use the ‘carrot and stick’ analogy, Option A seems to proffer plenty of carrots, whereas Option B seems to still rely more on sticks.

If using Main Option B, perhaps the moral is to aim to limit lump sums to items that can easily be proportioned, as well as to ensure that the accuracy of quantities is meticulous. However, in the context of all but the simplest of building projects, the ubiquitous ‘M&E’ installation is likely to present a challenge in relation to both of those aims.

In addition to routine payments under Main Option B, the payment mechanism also has to deal with payments which may become due as a result of instructed changes under the Contract.82 As with Main Option A, Option B provides for a fee to be applied in the case of compensation events, that fee being a percentage which is applied to the Defined Cost of the work.

Main Option C: Target contract with activity schedule

A target cost is agreed at the outset, with an incentive to the Contractor to achieve or to better the target, by offering a share in any savings. The cost of the Project is distributed into an Activity Schedule prepared by the Contractor, in a manner similar to Main Option A. The Activity Schedule under Main Option C is perhaps best understood as a distribution of the costs making up the Target Cost, where the sum of the constituent parts (activities) may or may not be greater than the whole Target Cost, depending on what the Contractor actually spends in terms of Defined Cost. Conversely, the sum of the constituent parts (activities) under a Main Option A Activity Schedule equals the whole contract lump sum. This distinction has an important impact on risk profile and incentivisation. It is one of many examples in NEC4 of where the status and implementation of things (whether documents such as an Activity Schedule or Defined Terms such as PWDD) is deliberately somewhat different depending on which main option has been chosen.

Target incentivisation

Note that with Main Option C, the allocation of risk can be significantly weighted by the share percentages allocated to each party to the NEC4 contract – hence the expression ‘pain/gain’ share. The intention is that the proportions are agreed, rather than imposed, as much of the potential benefit will be lost if excessive risk is priced as a contingency item which may or may not materialise. It would not be unusual for the share percentages for any pain and any gain to be unequal, subject to a proper assessment of which party is best able to carry certain project risks.

While target cost procurement strategies are not unique to NEC4, an architect’s first encounter with target costs may well have been, or will be, via NEC. There are now a number of examples of ‘repeat’ clients using Main Option C contracts, both in order to better performance relative to other procurement strategies and in order to compare performance between their own projects and supply chain teams.83

In implementing a target cost strategy, the first long-standing concept to relegate is that of having a contract sum – there isn’t one! There is only the Target Cost calculated for that individual project. An obvious, but sadly sometimes overlooked, factor in the success of target cost contracts is the accuracy of the cost plan upon which the Target Cost is based. Typically, most clients contemplating a target cost procurement strategy will be experienced clients, building projects of relatively large size, above average complexity and sensitive accountability for spending. Such clients often have experienced in-house procurement advisors or seek sophisticated procurement advice from consultants, which has both advantages and disadvantages. If the calibre of the advice given is high, there will undoubtedly be an emphasis on detailed risk analysis and risk management, which in turn are likely to lead to a careful setting of both the Target Cost and the pain/gain share percentages.

However, experience over the lifetime of NEC contracts suggests that very occasionally a somewhat ‘unreconstructed’ approach to risk management is adopted, whereby a client may be encouraged to shunt as much risk onto a contractor as possible. This way of thinking may have had its origins in older, more adversarial standard form contracts and may still be considered appropriate in some circumstances. Nonetheless, if it were to lead to a client managing to sign up a contractor on an NEC4 Option C contract with an artificially low Target Cost and a share percentage of 100% in any overspend relative to that target, it does not take much imagination to contemplate that the outcome might be very painful indeed, not just for the Contractor, but also for the Client.

The key point is that starting on the basis of the right Target Cost should be an even higher priority than agreeing the right share percentages for the risk of deviation from that cost. One of the most obvious ways of improving the accuracy of the target is to involve the Contractor(s) bidding for the work, in that they ought to have access to at least as accurate figures as cost consultants. If the list of contractors bidding for a job has been drawn up appropriately, such contractors ought to be in a strong position not only to contribute to accurate cost forecasting, but also to critique design solutions and offer useful value engineering input. This is not an NEC-specific point; however, an NEC4 Option C contract will have a massively improved chance of success if there really is ‘a spirit of mutual trust and co-operation’ between Client and Contractor teams with regard to the design of the contract as well as the building.

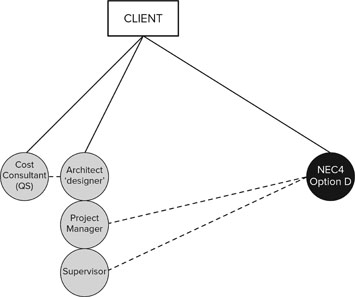

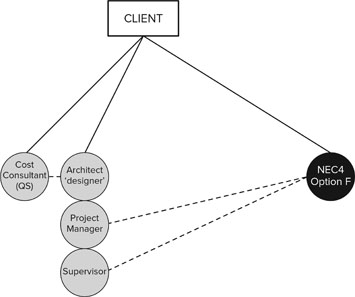

Figure 7:

NEC4 Main Option C: Architect acts as PM and Supervisor

Main Option D: Target contract with bill of quantities

As with Main Option C, the incentive to achieve the target relies on the requirement that any overspend is shared in a pre-agreed proportion between the parties.

With Main Option D, as with Option C, the fairness of the so-called ‘pain/gain’ share relies on both the accuracy of the cost planning to arrive at a realistic Target Cost and on the share percentages and share ranges agreed to form part of the contract.

With Main Option D, as with Main Option B, the minimal inaccuracy margin permissible in the Bill of Quantities, without it becoming grounds for a ‘compensation event’, effectively creates a remeasurement contract.

Looking at the payment mechanism envisaged with Main Option D in relation to building projects, there is clearly a need to assess risks associated with the accuracy of the Bill of Quantities, the accuracy of the cost plan upon which the Target Cost is based and finally the pain/gain share percentages. The overall risk profile that may emerge on a project under Main Option D could perhaps be a step too far for many architects and their building clients, without spending a disproportionate amount of time on pre-contract analysis and therefore a disproportionate amount of money on cost consultancy fees. This is not so much a criticism of the payment mechanism represented by Main Option D, but instead a recognition of the vast number of project types and sizes for which NEC4 is intended to cater. There follows a consequential acknowledgement that not all of the main option payment mechanisms will be equally suited to all project types or sizes.

The following is an example of a building project risk profile which might benefit from using Main Option D in terms of high motivation of both client and contractor to achieve a well-managed outcome:

- a large commercial project which includes infrastructure elements

- an experienced client wishing to keep control of the pricing document, i.e. the Bill of Quantities

- potential for early contractor involvement which could lead to a negotiated Target Cost

- acceptance that quantities of many items would be remeasured

- incremental pain/gain share percentages, i.e. where any spending over or under the Target Cost is not penalised or rewarded absolutely, but in proportion to the extent of deviation from the Target Cost, upwards or downwards

- desire for reciprocal pain/gain share percentages, i.e. not necessarily entirely equal share percentages for the Client and the Contractor as between ‘painful overspend’ and ‘gainful underspend’, but a correlation between the share percentage allocated to a party and that party’s ability to manage the risk.

There is anecdotal evidence among NEC4 users that Main Option D has been significantly less used on building projects than Main Option C, where an incentivised Target Cost is desirable. This is perhaps encouraging as it indicates that NEC4 users have become quite discerning about risk management on building projects.

Main Option E: Cost reimbursable contract

An ‘open book’ accounting policy is intended to operate, with the Contractor being paid at Defined Cost,84 plus a percentage fee for profit and overheads.

Open book accounting is a concept which has been completely embraced in some quarters of the construction industry and yet is still regarded with a degree of disbelief in other quarters. The idea of disclosing actual invoices and declaring profit and overhead percentages also seems to find more favour in some countries than others. Ultimately, comfort with a payment mechanism which is based upon open book accounting is as much a matter of culture as it is of contractual arrangements.

Main Option E is predicated on the Contractor being able to recover costs and overheads and make a profit and there will be some building clients whose reaction to this approach might be ‘Why should contractors carry no risk?’ However, experience should tell the building industry that ‘risk shunting’ in the opposite direction rarely benefits clients, as contractors who are expected to gamble in terms of their ability to make any profit will try to protect their interests. This is not an NEC4 phenomenon, but merely human nature playing its part. With any building contract, unless there is a payment mechanism which acknowledges profit as a right for contractors, contractors will tend to attempt to build in contingencies of some sort as a way of protecting their legitimate expectations in carrying out work for clients.

As envisaged with any cost reimbursable type contract, NEC4 Option E permits an early start on site, with relatively little final information available to the Contractor. While this represents a risk to the Client in terms of outturn cost on a building project, the decision to use any of the NEC4 main options should be founded on sound procurement analysis.85 It may be that the Client has set time as a key parameter on a particular project, in which case Main Option E may offer advantages.

The manner in which an element of building work is costed under Main Option E is independent of the timing of the instruction to carry out that element of work. In other words, because of the way in which payment at intervals is assessed under Main Option E, it makes no difference to the calculations whether the assessment includes items which were part of the contract at the outset, additional items which have been instructed post-contract, or a mixture of the two. Nonetheless, because of the inextricable link under NEC4 between time and money within the compensation event procedure, the contract programme will clearly be extended by significant post-contract instructions. Architects need to weigh up carefully in their procurement analysis with their clients how best to control not only the parameter of time relative to the other parameters, but also the potential benefits of an early start on site – which Main Option E is suited to – relative to a longer duration on site which could arise from compensation events.

Main Option F: Management contract

There is anecdotal evidence that this main option has been the least used of all the NEC main options across all sectors of the construction industry. Perhaps the reason for this is simply that the other five main options already offer significant flexibility of payment mechanisms and NEC4 as a whole offers significant tailoring of procurement routes; i.e. a management style procurement route can be achieved under NEC4 without necessarily incorporating Main Option F.

The intention with Main Option E is that the Contractor manages the subcontract packages and prepares forecasts of the total Defined Cost86 of all work and receives this plus a percentage fee.

Possibly the best way for architects to assess the relative benefits of Main Option E when advising their clients on the assembly of an NEC4 contract is to focus on the degree of subcontracting desired and on how well prepared the scope of those subcontract packages is likely to be at the point when the NEC4 contract is to be entered into.

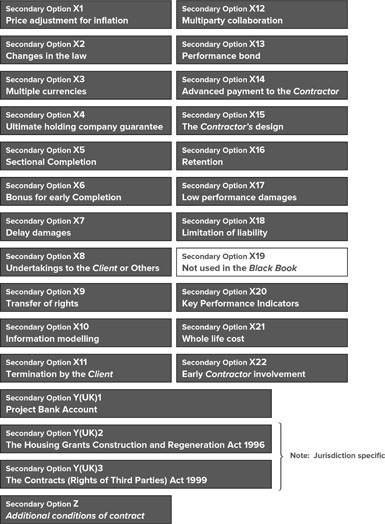

Secondary option clauses

The secondary options can be operated on a pick-and-mix basis in any combination to tailor the contract as closely as possible to the needs of the project (see Figure 12).

These secondary options broadly fall into two categories:

- Options which introduce choice in standard procedures. Those options containing processes that conventionally have been included in the contract conditions of standard form contracts, whether needed or not, i.e. without giving a choice. An example of such a process would be Secondary Option X16: Retention.

- Options which introduce additional standard procedures. Those options containing processes that conventionally have not been available in standard form contract conditions without the introduction of bespoke drafting. An example of such a process would be Secondary Option X3: Multiple currencies.

It is important to note that there is no obligation to introduce any of the secondary options; an NEC4 contract is operable with none of them included. Conversely, most of the secondary options are not mutually exclusive to one another. That is, in theory, most of the secondary options could be included together in an NEC4 contract, the exception being that Secondary Option X20: Key Performance Indicators is not used with Secondary Option X12:

Multiparty collaboration. However, some of the secondary options and individual main options are mutually exclusive; this is not for the sake of complexity, but rather a direct response to the practicalities of project management. The logic behind the prohibition of any incompatible options becomes clear in looking at the individual secondary options.

Figure 12:

NEC4 Secondary Option Clauses

Secondary Option X1: Price adjustment for inflation

[Used only with Main Options A, B, C or D]

Architects and their building clients will be familiar with standard form contracts offering the potential for the Client to carry the risk of price increases. However, building clients in the UK have been reluctant for decades to voluntarily take on this risk and it is unlikely that Secondary Option X1 will be put forward on a building project in the UK. The provision is offered to cater for requirements in sectors where it is more usual for the Client to be well placed to carry the risk of price increases. It is also offered in recognition of NEC4 potentially being used in countries with high inflation, where the Contractor may be unwilling, or unable, to carry such a risk without being priced out of contention.

The reason that Secondary Option X1 is only used with Main Options A, B, C or D is simply that the payment mechanisms under Main Options E and F already entitle the Contractor to be paid on the basis of costs which include any inflation at the time of payment.

Secondary Option X2: Changes in the law

The risk of legislative changes during the currency of a contract is clearly higher under some jurisdictions than others. There is also the issue of whether a change in the law in a particular country is applied retrospectively or not. The impact on construction contracts will consequently be quite variable, depending on where the project is. Looking specifically at building contracts in the UK, the perceived risk is very low, although the procurement route will have an influence. For example, the risk of changes in the Building Regulations per se is quite high; however, because such changes do not apply retrospectively, and adequate notice is given of their coming into force, the actual risk on a particular project is normally quite low. The procurement route will have an impact on the risk as it may make a difference as to which party to the building contract would be liable for post-contract legislative changes. Using the same example of Building Regulations, the Contractor might be at greater risk under a design and build procurement route, where the time period is long between entering into contract and sign-off of design packages requiring Building Regulations approval.

Architects and their building clients will need to consider this secondary option on its merits for a particular project. Typically, it is not an option which would be considered necessary on many building projects in the UK. Where the Contractor is to be responsible for large amounts of design, or is working on a project of long duration, there might be a financial advantage to the Client at tender stage in incorporating this secondary option and accepting a risk which would otherwise rest with the Contractor.

In the case of working on projects in other countries, architects would need to be familiar with the differences in default risk in those countries. For example, the risk of changes in the law pertaining to technological standards as the project progresses, i.e. not retrospectively, would as a default rest with contractors in Germany.87

Secondary Option X3: Multiple currencies

[Used only with Main Options A or B]

It is increasingly common on construction projects for components to be imported from other countries. NEC4 is designed to be used potentially in any country, so whether, for example, Japanese air handling units and German curtain walling are being imported for a UK building project, or Swiss precast concrete elements are being exported for a Chinese hydroelectric project, there are many instances where contractors may have to pay for components in more than one currency.

The idea behind Secondary Option X3 is that the Client may be in a better position to carry the risk of currency fluctuations than the Contractor. In such a case, by incorporating Option X3, the Client can agree to pay for certain items in their currency of origin (e.g. yen or euros), while other items are paid for in the default currency of the contract88 (e.g. pounds sterling). The use of Secondary Option X3 therefore allows the exchange rate risk to be managed by the Client rather than the Contractor.

The amount of payment in other currencies is capped in the contract to an agreed level and an exchange rate is stated. In practice, this means that where Secondary Option X3 is used, the Client can manage the exchange rate risk in quite a sophisticated manner, such as by the use of hedging finance with forward contracts, etc. This facility is particularly critical in times of exchange rate volatility, for example, the Brexit period.

Clients and their architects may feel that this Secondary Option X3 requires excessive financial management skills; however, it should be seen as the option that it is, and it is clearly more suited to certain clients than others. It should also be taken into consideration that some contractors are perfectly able to manage exchange rate risk without detriment to clients – an obvious example of this would be a multinational contracting firm with offices in both countries and therefore constantly using both currencies.

Any decision to use Secondary Option X3 will be entirely project- and organisation-specific.

Secondary Option X4: Ultimate holding company guarantee

This will be a familiar concept to architects who are used to working on larger projects. Experienced clients who are building high-value projects often require some form of security for the performance of contractors. A parent company or ultimate holding company guarantee may be an appropriate form of security, albeit it relies on a particular contractor having an ultimate holding company.

This may be a useful provision on large-scale building projects and it is relatively easy to implement by virtue of it being a standard optional clause.

Where Secondary Option X4 is being considered for a building contract, it should ideally be done in the context of considering as an alternative Secondary Option X13: Performance bond. While the two secondary options are not mutually exclusive, it might be considered somewhat extreme to include both; it might also be unnecessarily expensive, given that both forms of security will normally attract a fee or premium payment.

Secondary Option X5: Sectional Completion

This will be a very familiar concept to most architects and, as in other standard form contracts, is a provision which allows different parts of a project to be completed sequentially. It is intended for use where a client requirement for such sequential completion is foreseeable from the outset.

Secondary Option X5 can be implemented on the basis that the entire project is split into particular sections, or on the basis that critical parts are identified as discrete sections, with the remainder being left within the ‘whole of the works’. When using Secondary Option X5, ensure that there is complete clarity as to which parts of the works fall into a particular section; depending on the nature of work to be done, this may require detailed written and/or graphic description to be included within the Scope.

The Contract Data needs to be filled out with particular care when Secondary Option X5 is used. If the entire project has been split up into sections, then it follows that in the Contract Data the completion date for the whole of the works will be the same date as the completion date for the last identified section. If only certain critical parts have been identified as discrete sections, then the completion date for the whole of the works will be a later date than the completion date for the latest identified section.

In using Secondary Option X5, it follows that while not all of the works need be allocated to one of the sections, if a project team feels more comfortable doing so, then the last identified section would effectively be on an ‘and everything else’ basis, and the completion date for the whole of the works would be the same date as the completion date for that last identified section.

Secondary Option X6: Bonus for early Completion

This is likely to be an unfamiliar concept to most project teams in the building sector. It is perhaps helpful to see the idea of clients rewarding contractors for finishing early as no more than the converse of clients penalising contractors for finishing late. That is not to say that there is any necessary connection between the two under any form of building contract, but rather a way of comprehending the partnering principles behind Secondary Option X6, i.e. incentivisation and reciprocity of potential benefits.

In completing the Contract Data for Secondary Option X6, note will need to be taken of whether Option X6 is to operate on a single completion date or on Sectional Completion dates because Secondary Option X5 is also included.

Secondary Option X7: Delay damages

This will be a known concept for most project teams in the building sector. As in other standard form contracts, this is a provision which allows clients to legitimately penalise contractors under the contract for finishing late. In implementing Secondary Option X7 under English law, it is important to remember that actual penalties are unenforceable and that the delay damages entered into the Contract Data must remain a genuine pre-estimate of the Client’s loss if the Contractor were to finish late.

Architects using NEC4 for the first time may be somewhat surprised to find that delay damages are optional, as similar damages are a well-established norm under other standard form contracts.89 However, experienced NEC users are likely to look at the range of contractual measures available to incentivise contractors to stay on programme. It would be a waste of NEC4’s potential to only use Secondary Option X7 because of its familiarity. In isolation, a negative incentive is still a somewhat blunt instrument with which to tackle the issue of keeping complex building projects on programme. Hence, there is an argument for at least considering the relationship between Secondary Options X7 and X6.

There is also a need to look at an NEC4 contract holistically; the perceived need to include Secondary Option X7 would almost certainly be judged differently on a building project under Main Option A than under Main Option E.

As with Secondary Option X6, in completing the Contract Data for Secondary Option X7, note will need to be taken of whether Option X7 is to operate on a single completion date, or on sectional completion dates because Secondary Option X5 is also included.

Secondary Option X8: Undertakings to the Client or Others

This secondary option is new to NEC4 and provides a standard mechanism for giving parallel rights to specific parties. Architects will be accustomed to the requirement on some building projects for collateral warranties to be obtained, whether, for example, from subcontractors to clients, or from contractors to funders. Secondary Option X8 provides a clear way of incorporating such requirements into an NEC4 contract by reference to the Contract Data and the Scope, thus ensuring any required undertakings are obtained in the required format and in a known timescale.

Secondary Option X9: Transfer of rights

This secondary option is new to NEC4 and provides for design copyright to be transferred to the Client from the Contractor and from subcontractors in accordance with requirements stated in the Scope. Whether architects will consider this secondary option to be helpful will depend on the project and the procurement route; however, as with all the secondary options, it should be discussed with building clients in individual cases.

Secondary Option X10: Information modelling

Secondary Option X10 is new to NEC4 and provides detailed procedures for the incorporation of information modelling into projects. Architects working with building clients will be used to referring to BIM;90 however, NEC4 uses the generic description because of its multidisciplinary application. Depending on the nature and size of projects, many architects and their building clients will regard BIM procedures as essential rather than optional, in which case they should incorporate Secondary Option X10 in their NEC4 contracts.

Secondary Option X11: Termination by the Client

This provision for the Client to terminate without specific reason used to be part of Core Clause Section 9 in NEC3, but it has been taken into the secondary option level in NEC4. This change offers greater reciprocity of rights and obligations between the parties. Architects advising building clients would be well advised to draw this change to their clients’ attention and discuss whether the inclusion of Secondary Option X11 might be desirable on a particular project.

Secondary Option X12: Multiparty collaboration

[Not used in conjunction with Secondary Option X20]

Secondary Option X1291 is a subject in its own right and is discussed in more detail in the context of collaborative working as a whole – see Chapter 4.

The key message is that Secondary Option X12 acts as extra ‘cement’ with which to ensure the partnering relationship stays together and can achieve sophisticated aims; it is not the sole vehicle for creating a partnering relationship in the first instance: that is NEC4 itself.

Secondary Option X13: Performance bond

As with Secondary Option X4, providing a form of security to clients for the performance of contractors will be a familiar concept to architects used to working on larger projects. In this case, the security is ultimately provided by a bank or insurer not by the contracting organisation.

While this provision is in principle relatively easy to implement, being a standard optional clause, care must be taken over stating the amount of the performance bond required,92 describing the form of the bond required93 and outlining the type of surety94 which will be acceptable.

Where Secondary Option X13 is being considered for a building contract, sensibly it would not be in addition to Secondary Option X4: Ultimate holding company guarantee, as this would normally be considered somewhat excessive. This is not an NEC4-specific point, but rather common sense in the context of how best to protect clients against potential non-performance of contractors.

Secondary Option X14: Advanced payment to the Contractor

This provision for the Client to make an advanced payment to the Contractor is something which will rarely be considered on some types of building project but will be regarded as almost essential on other types of building project. As with many of the secondary options, this is not a novel concept; NEC4 is merely recognising common contractual requirements and pre-drafting provisions for such requirements so that they may be picked off the contractual ‘shelf’ and suitably mixed with the other contract clauses to achieve the required overall ‘recipe’.

An example of this secondary option being beneficial on a building project would be where a large amount of prefabricated structural steelwork was part of the Scope of the project, its lead-in time was critical, and the fabricators required the raw steel to be purchased in advance of the fabrication.

Secondary Option X14 can operate in two ways. First, the Client can simply agree to pay a sum of money in advance to the Contractor for a particular expenditure, and this sum is then paid back in instalments95 at payment assessment intervals. Second, where large sums of money might represent an unacceptable risk, the Client may also require an advanced payment bond. In the latter case, additional attention must be paid in completing the Contract Data to include a description of the form of the advanced payment bond required96 and the type of surety97 which will be acceptable.

Secondary Option X15: The Contractor’s design

This secondary option is a significant one for architects, especially those who regularly work for design and build contractors.

Essentially, the position on design liability under English law is different from other jurisdictions, in that ‘reasonable skill and care’ is an obligation peculiar to common law. The default under most jurisdictions is ‘fitness for purpose’ and because NEC4 is designed to be operable under any jurisdiction, an active choice has to be made to limit liability to ‘reasonable skill and care’. If the Scope is drafted in clear enough terms, that limitation of liability can legitimately be made in the Scope. However, by incorporating Secondary Option X15, the standard of care can be globally limited, which in many cases may be preferable.

Certainly, an architect contemplating engagement within a design and build procurement route by contractors who are themselves under an NEC4 main contract would do well to ask whether Secondary Option X15 has been incorporated!

Secondary Option X16: Retention

[Not used with Main Option E]

It may come as a slight surprise to architects that retention is an optional concept under NEC4. It behoves us perhaps to reconsider the intended purpose of retention, in that there are apparent instances of it being abused more than used under some standard form contracts.

Retention is generally accepted to serve a useful function in incentivising contractors to return to site to deal with the eventuality of any defects which manifest themselves post-completion. Under some standard form contracts, it is also often used as leverage to ensure contractors continue to work on elements of a building which were manifestly incomplete, or defective, when completion was certified in order to give access to a Client. In either scenario, retention that is deducted from the outset of a project is a fairly blunt instrument with which to control post-completion quality and in any case tends to push contractors towards negative cashflow.

In contemplating NEC4, there is a need to look at retention in the context of collaboration and incentivisation. Returning to the carrot and stick analogy, it is arguable that retention has always been used as a ‘stick’, not a ‘carrot’. Not only are sticks inherently dangerous in the arena of collaboration but also using a stick from the outset of the Contract to tackle a potential post-completion issue seems perverse. NEC4 offers two alternative approaches. First, the approach of deciding that other contractual provisions could provide adequate protection from potential defects and therefore Secondary Option X16: Retention will not be necessary on a particular project. Second, where it is decided that retention is necessary in principle, Secondary Option X16 envisages that it will not be deducted from the outset but only from a point when the cumulative value of the works has reached a certain value, i.e. the so-called ‘retention free amount’.98 Only after this value has been reached, which typically would be shortly before completion, will retention be deducted; in practice this significantly reduces the period during which the Contractor has to finance the retention sum, without reducing the post-completion protection to the Client.

This secondary option is not used with Main Option F on the policy principle that retention is inappropriate to projects with predominantly subcontracted work.

Secondary Option X17: Low performance damages

This particular secondary option is unlikely to apply in the context of a building project. It is primarily intended to provide protection to clients on projects where the scope of the intended work encompasses items, or installations, when it may not be a simple case of either they work or they do not work, but rather that they do not work quite as well as they should! In practice, Secondary Option X17 will provide useful protection to clients on projects such as industrial/processing plants where the designed output may not be fully achieved, either temporarily or permanently.

This secondary option would also protect the Contractor on certain types of project: a defect causing low performance could be accepted under the terms of a contract incorporating Secondary Option X17, rather than having to be treated as a breach of contract without Secondary Option X17.

Secondary Option X18: Limitation of liability

This secondary option was introduced with the third edition of NEC. It was probably a policy decision based on consumer demand to be able to cap liability at some point, irrespective of the type of project and contract value.

Certainly, on most building projects being carried out under English law, there has been a perceptible trend to limit liability in some manner. The reason this is a secondary option under NEC4, rather than being within the core clauses, is that the contract flexibility is of paramount importance and it is not desirable under any jurisdiction to have core clauses which might get struck out. Secondary Option X18 is certainly one of the secondary options which architects should discuss carefully with their clients before any decision is made regarding its incorporation or otherwise. In the case of contractor negotiations, it is prudent to consider discussing the inclusion of Secondary Option X18 with the potential contractors.

In the context of a design and build procurement route under an NEC4 main contract, an architect employed by the Contractor would sensibly wish to see Secondary Option X18 incorporated because liabilities should relate to insurance cover99 and no architect is going to carry professional indemnity insurance with limitless cover.100

Secondary Option X20: Key Performance Indicators

[Not used in conjunction with Secondary Option X12]

The only reason Secondary Option X20 should not be used with Secondary Option X12 is because the latter potentially offers an even more sophisticated approach to Key Performance Indicators, linked into incentivisation; these secondary options are therefore designed to be used on an either/or basis, not simultaneously.

Key Performance Indicators, or KPIs, as they are commonly known, became a feature of many contracts where a collaborative ethos was being encouraged. Their role is essentially to assist in benchmarking relative performance in specific areas within a construction project and to incentivise improved performance. Secondary Option X20 is intended to provide a relatively simple contractual basis upon which performance targets can be stated, measured and monitored.

Secondary Option X21: Whole life cost

This secondary option is new to NEC4 and is an opportunity for the Client to benefit from the Contractor proposing a change to the Scope to reduce the costs associated with operating and maintaining a project.

Architects are likely to be considering whole life cost in any case and may deem this option unnecessary if they have been involved in the design of a building project from the outset. However, if architects were employed at a later stage under a design and build procurement strategy, they might consider that operation and maintenance costs could be reduced, and they would be well placed to assist the Contractor in preparing the quotation required under Secondary Option X21.

Secondary Option X22: Early Contractor involvement

[Used only with Main Options C or E]

Secondary Option X22 is new to NEC4 and provides for the Contractor being involved from an early stage of a project and contributing to the control of a budget.101 Architects will need to consider carefully how this secondary option relates to the relative expertise of all project contributors, and the proposed allocation of design responsibility, in order to decide whether it is likely to be helpful for a particular project or client.

Secondary Option Y(UK)1: Project Bank Account

This UK-specific secondary option is new to NEC4 and provides for a bank account to be opened by the Contractor which will enable security of payment from Client to Contractor and from Contractor to Named Suppliers.

A trust deed is executed between the Client, Contractor and Named Suppliers. A joining deed is envisaged for additional suppliers to be included at a later date, after the original trust deed has been executed.

This provision may be helpful on larger, higher risk projects, and architects can discuss the possibility with their clients.

It is unclear why this new provision has been classified as a UK-specific secondary option because the principle of security of payment through escrow accounts is well known under other jurisdictions. Indeed, the desire to increase security of payment might be greater in the case of cross-border contractual relationships which could be under jurisdictions other than English law.

Secondary Option Y(UK)2: The Housing Grants, Construction and Regeneration Act 1996

[Only to be used on UK projects where the Act applies]

Secondary Option Y(UK)2 relates specifically to legislation which extends to England and Wales and where the relevant part of that legislation also extends to Scotland.102 The purpose of Y(UK)2 under NEC4 is to ensure that the payment provisions of the legislation are complied with. (NEC4 does not deal with adjudication as part of Y(UK)2.)103 It therefore follows that a contract for any project in England, Wales or Scotland, which comes under the definition of a ‘construction contract’,104 should have Secondary Option Y(UK)2 incorporated.

Irrespective of the specific use of NEC4, architects advising clients will need to be familiar with the project types which will be deemed exceptions105 to the definition of a construction contract, and where the payment provisions of the legislation therefore need not be complied with; i.e. in the case of NEC4, the projects which do not require Secondary Option Y(UK)2 to be incorporated.

Secondary Option Y(UK)3: The Contracts (Rights of Third Parties) Act 1999

[Only to be used on UK projects where required]

Most UK-based architects will be familiar with the common advice to exclude the operation of the Contracts (Rights of Third Parties) Act 1999 because the legislation may be contracted out of.

Secondary Option Y(UK)3 can be seen as a slightly more subtle approach. The legislation can be contracted out of entirely by incorporating Secondary Option Y(UK)3 and by remaining silent as to any third-party identity. However, by naming a particular third party, or class of third party, in the Contract Data, it is possible to allow the Act to apply in a specifically controlled manner. In practice, this may be a preferable approach on building projects where third parties, such as funders or tenants, require rights, rather than having a number of specially drafted collateral warranties.

NEC4 per se does not alter the decision-making process in relation to whether or not to allow either collateral warranties or invocation of the Act; it is merely that Y(UK)3 facilitates the practical process where a decision has been made to either completely exclude or specifically invoke the Act.

Secondary Option Z: Additional conditions of contract

Any so-called ‘Z-Clause’ should be very carefully considered and if strictly necessary, it should be drafted in a style compatible with the drafting of NEC4.

The status of a Z-Clause is that it augments the other contract clauses; it should not purport to amend them.

There is a strong argument for Z-Clauses to be used only if genuinely necessary. In the early days of NEC contracts, there were many examples of copious amounts of Z-Clause drafting, much of which was superfluous and some of which was downright dangerous: it either confused the meaning of core clauses or sought to change that meaning without necessarily dealing with the consequences of an isolated change. Such overzealous drafting thankfully appears to have diminished significantly, no doubt as a result of the now widespread use of NEC contracts and an ever-improving understanding of them.

Nevertheless, architects should remain vigilant for unnecessary Z-Clauses, which could creep in as a result of clients seeking legal advice from lawyers not entirely familiar with NEC. For reasons of democracy and moving projects forward, there might conceivably be times where letting a superfluous Z-Clause remain is a reasonable course of action, in that it is very unlikely to be harmful. However, if an architect or their client is unlucky enough to be presented with a long list of Z-clauses which purport to amend core clauses, they must resist! A good clue when checking for such clauses is if the drafting style of Z-Clauses appears to be old fashioned in comparison with that of the NEC4 standard clauses. This would suggest that a lawyer, quantity surveyor or even an ill-advised architect has returned to the older style standard form contract drafting originating from the Victorian era, possibly having found the absence of such drafting in NEC4 somewhat unnerving.