2

So What Is Good Management Really?

Who was your best boss ever? And how about your worst boss? And why? If you have never answered this question, have a quick stab at it now. I have done this exercise with hundreds of people and the results are quite revealing – about you, as well as about the boss in question. Table 2.1 lists some typical answers.

Table 2.1 What Makes a Good Boss? What Makes a Bad Boss?

| Best boss |

| “Incredibly challenging and supportive at the same time. Pushed me beyond my comfort zone and held me accountable, but also cared about me as a person.” |

| “He is incredibly supportive, goes out of his way to help me, has an infectious ability to create confidence in others.” |

| “She made the team feel like a family – we are all in this together; she shielded us from top-down interference.” |

| Worst boss |

| “He would go for people in a scheming, manipulative way, and wear them down.” |

| “He was never available, just gave orders, his ideas were the only ones that counted; he cast a shadow over the team.” |

| “She was autocratic, arrogant and imposing, not afraid to put people down in public; everyone was disposable.” |

We will come back to these examples – and your own experiences – later. The purpose of this chapter is to put some structure around the concept of good management. I will use plenty of specific examples, and I will also present some more systematic data that I collected over the last couple of years. If Chapter 1 was all about understanding the high-level argument that we need to improve the practice of management, this chapter makes the complementary case at the individual level. However, before getting into the meat of the story, I need to clarify a few pieces of terminology.

Management and Leadership

I define management as bringing people together to accomplish desired goals. This definition works at two different levels. It applies to the collective activities of the people running an organization and it involves the development of formal and informal systems to enable effective coordination and decision-making. It also applies at an individual level – to the activities of each and every one of us as we go about our day-to-day work. In my previous book, Reinventing Management, I was concerned primarily with system-level management, and I argued that we might be able to develop better collective ways of working if we built our model of management from a different set of starting assumptions.

In this book I am focusing primarily on individual-level management – on the things you can do to bring a team of people together to accomplish your desired goals. Obviously this individual form of management does not happen in a vacuum, as the way you act is inevitably constrained by the formal and informal systems that surround you. But every manager has some degrees of freedom and chances are you have more space for discretionary behavior than you like to think you do. One of the themes of this book is about pushing back on, and even stretching, the invisible boundaries around your sphere of influence.

If management is about bringing people together to accomplish desired goals, leadership is a process of social influence. A leader is someone who is able to define and articulate a vision sufficiently clearly that others seek to follow them. Leadership is, to a large degree, about how a person presents him or herself to those around them and success is defined in terms of the quality and quantity of followers who he or she gains.

Management and leadership are therefore complementary activities, and to be effective in an executive role you need to be able to do both really well. It is often said that executives get into trouble because they are focused on management rather than leadership, meaning that they are too busy maintaining the status quo to develop a point of view on what needs to change. However, I think the reverse is equally true: some executives get into trouble because they are focused on leadership rather than management. In other words, they are so preoccupied with future opportunities, and with their image, that they lose touch with the day-to-day realities of the business they are running. The best executives, in my view, are those who are equally at home with both the big picture and the microlevel details. In the opinion of Jim Collins, they are adept at zooming in and zooming out. In the words of Standard Chartered CEO, Peter Sands, they are able to swoop and soar.

If you are a regular reader of business books, you will be familiar with the management versus leadership debate that has preoccupied academics for the best part of 30 years. In my view it is not just a tired debate, it also represents a false dichotomy. Indeed some languages, such as Swedish, have a single word (ledarskap) that covers both aspects of the executive's job. I have written extensively about this, but only because I feel the obsession with leadership has led to a dangerous diminution in the perceived importance in the practice of management.

All of which, hopefully, explains why this book is framed around management and not leadership. I am interested in how you can be more effective in your role, that is, bringing people together to accomplish desired goals. Some of what this involves may well be characterized as leadership, but that doesn't bother me in the slightest. What matters, of course, is that you figure out ways of being more effective in your work, not the label we put on those activities.

I also use the word “boss” quite frequently – not least in the book's title. Boss simply refers to the person or persons you report to (or how your team view you). While some people may feel that boss sounds too authoritarian or traditional, I don't mean it that way – I see it as a simple and neutral way of describing the person who sits above a subordinate in a hierarchical system.

Bosses We Love to Hate

There are plenty of bad managers out there. I have had my share of small-minded, aloof, egotistical, thoughtless, short-fused (pick any combination) bosses, and my guess is most of you have as well. People usually find it much easier, and more fun, to talk about their “worst boss” than their “best boss,” and that is why I typically start a discussion of management from this direction. I am not alone in this approach. Stanford Professor Bob Sutton has written two best-selling books – The No Asshole Rule and Good Boss, Bad Boss – with weird and wonderful accounts of how the workplace brings out the worst in some people. The reason that Dilbert, The Office, and Fawlty Towers are so funny is because they center on authority figures who are as oblivious to their own flaws as they are incompetent. A major Hollywood movie from 2011 was called Horrible Bosses. I have also contributed to the bad management debate using those old favorites, the Seven Deadly Sins (see Box 2.1).

Here is my stab at defining what bad management looks like, using those old favorites, the Seven Deadly Sins. I developed these ideas during seminars with executives where we discussed their experiences of good and bad management. Of course, a bit of artistic licence is necessary here, to adapt words like “greed” and “lust” to corporate life, but on the whole I think they work pretty well. I have even put a little questionnaire together to help office workers across the land to rate their line manager. Does your boss succumb to only one or two of these sins? Or is he a seven-star sinner?

I have illustrated some of the sins with examples of famous Chief Executives, because these are stories we are all familiar with. But of course the sins apply at all management levels in the organization – they are as relevant to the first-line supervisor as they are to the big boss.

A greedy boss pursues wealth, status, and growth to get himself noticed. In short, he is an empire builder, and we don't have to look far to find examples of empire-building bosses. Perhaps the stand-out example today is Eike Batista, the Brazilian entrepreneur who has made the EBX Group (energy, mining, and logistics) into Brazil's fastest-growing company and him into the eighth-richest person in the world. Formerly married to a Playboy cover-girl and an ex-champion powerboat racer, he has now set his sights on becoming the first person in the world to amass a $100 billion fortune.

Lust is also about vanity projects – investments or acquisitions that make no rational sense, but play to the manager's desires. Edgar Bronfman, heir to the Seagram empire, leaps to mind here. To the “widespread astonishment” of the business world, he traded in the company's valuable holding in chemical giant Du Pont in order to buy up Universal Studios. A quick glimpse at his vitae helps explain his motives – even in his teens he was dabbling in song-writing and movie-making.

Wrath doesn't need a whole lot of explanation. “Chainsaw” Al Dunlap, Fred “the shred” Goodwin, and “Neutron” Jack Welch were all famous for losing their cool. We see this at all levels in the hierarchy – my first boss would turn bright red and start shaking before he yelled at some poor soul for failing to debug a piece of software properly.

Gluttony in the business world is where a manager puts too much on his proverbial plate. He needs to get involved in all decisions, he needs to be continuously updated, he never rests. We call this micromanaging and Gordon Brown did it during his brief stay at Number 10 Downing Street, where he insisted on reviewing minor departmental decisions and expenditures. It's not much fun working for such bosses, because they have a tendency, in Charles Handy's famous phrase, to “steal” your decisions. There is also a risk that decision-making gets stuck: Lego CEO, Jurgen Knudstorp, notes that companies are far more likely to fail through “indigestion” than through “starvation,” as Gordon Brown's Labour government discovered.

Healthy pride quickly tips over into hubris – an overestimation of your own abilities. In all the recent corporate crises – News International, Nokia, BP, even Toyota – there was tangible evidence of hubris in the manner and words of the executives at the top. Pride does, indeed, go before a fall. Perhaps the biggest tale of misplaced pride in recent years was Enron – its executives liked to think of themselves as the “smartest guys in the room” and they shortened the company's vision from becoming the “world's leading energy company” to becoming “the world's leading company.” And we all know what happened there.

Envy manifests itself most clearly when a manager takes credit for the achievements of others. However, envy also rears its head in less obvious ways: when a manager chooses not to promote a rising star, for fear of showing up his own limitations, or when he keeps important information to himself, rather than sharing it with his team.

Sloth is workplace apathy – the managers who fall prey to sloth are simply not doing their job. They are inattentive, they don't communicate effectively, and they have no interest in their team's needs. Instead, they focus on their own comforts and, quite often, on personal interests outside of the workplace. We have all seen glimpses of sloth in the workplace: the boss who takes long lunch breaks but is “too busy” to sit down with us; the colleague who doesn't deliver on his part of a proposal; the executive who promises to get back to you on something but never does. Although sloth rarely makes it to the headlines, I suspect there are shades of sloth in most managers. The cost of sloth can be very high when management fails to make necessary strategic adjustments when the business is in crisis.

If you are a boss (and most of us are), do your own self-assessment and figure out which of these sins you are most prone to. Remember – no-one is perfect and the chances are you are guilty of at least one of these sins. If you are brave, ask your own team to rate you, as a one-off exercise or as part of a broader 360-degree assessment process. The most challenging part is acting on the information you receive. However, the advantage of this approach, compared to other similar exercises, is that at least we can now put a label on what you are trying to avoid.

Answer the following seven questions for yourself or your current boss. Answer each question on a 1–5 scale, where 1 = “not at all” and 5 = “to a very large extent.” Then count up the number of 4s and 5s – that tells you how many sins he or she is prone to.

Why this fascination with bad bosses? Partly, it is just about getting some light relief when work gets a bit tiresome. By swapping stories about the flaws of our managers, we are reassured that we are not alone, and we generate empathy from others. But bad bosses also provoke a sense of moral outrage in us, in the same way that we get upset about corrupt politicians or crooked policemen: bosses are authority figures, with responsibility for others, and as such they should behave better.

Bad bosses can also, potentially, be a useful source of insight. By playing up their worst flaws, we highlight the things we should not be doing ourselves. Indeed, it is often said that we learn more from failure than from success, because it forces us to confront problems and change our behavior.

All of which is true. However, there are also a couple of reasons to be cautious with our focus on negative role models. First, we have a tendency to accentuate the negative elements of a manager's personality when he has failed in a task, just as we accentuate the positives when he has been successful. For example, up to his retirement in 2007, John Browne was lauded for transforming BP into a world-leading oil and gas company. Commentators praised his deep intellect, his decisive and bottom-line focused style, and his visionary leadership. Five years later, in the wake of the Macondo well disaster, the interpretation of John Browne's management style has been revised. He has been accused of “penny-pinching” and creating “dreadful bureaucracy and inefficiency,” as well as being “aloof” and “a man highly unaware of the impact of his actions.1” Which one is the real John Browne? Well, there is some truth in both perspectives, but the point is that our interpretation is heavily skewed by how successful the person seems to be – the so-called “halo effect.2”

For another example of the same phenomenon, consider Box 2.2: Hero or Zero?, which features quotations about the leadership styles of Apple's former CEO Steve Jobs and Royal Bank of Scotland's former CEO Fred Goodwin. In many respects, the two leaders had similar styles – very pushy, forthright in their views, intolerant of failure, convinced of their own genius. However, because of the way history turned out, Jobs' style was deemed to be a key factor in his success, whereas Goodwin's style was interpreted as the seed of his downfall.

These quotes below are about two famous CEOs: Steve Jobs and Fred Goodwin. One is revered, the other is reviled. But their personalities and management styles were not a million miles apart. See if you can guess which of these quotes refer to Jobs and which to Goodwin4.

The underlying problem, then, is that many of the “bad” attributes of management are often beneficial to some degree. Intolerance of mediocrity helps to spur everyone on. Arguing can be a way of exposing the truth. Getting angry can be a way of making a point. Again, Steve Jobs is the classic example: as Debi Coleman, one of his team at Apple, recalls in his biography, “He would shout at a meeting, you asshole, you never do anything right, it was like an hourly occurrence. Yet I consider myself the absolute luckiest person in the world to have worked with him.3”

This leads to the second key point – that what is defined as good or bad management depends on the personality and working style of the employee. Debi Coleman loved working for Steve Jobs, because she could cope with his abrasive style and valued his ability to spur her to new heights. But many others couldn't handle him, or didn't want to put up with his childish outbursts. Jeff Raskin was one influential manager who parted ways with Jobs during the early years at Apple. In a parting shot to the board, Raskin wrote that Jobs “is a dreadful manager … he acts without thinking and with bad judgment … he does not give credit where due.5”

Of course, we have known for many years that one hallmark of a good boss is his or her ability to “personalize” their style to the needs and concerns of individual employees. Indeed, this ability to get inside the heads of your employees, to understand what makes them tick, is one of the key themes in this book. But the trouble is, these nuances often get lost in discussions about good and bad management, with the result that we fall back on what Jeff Pfeffer and Bob Sutton call dangerous half-truths – statements that are usually, but by no means always, true. So working for a “micromanaging” boss isn't usually much fun, but actually some people are reassured by having their work carefully reviewed, and in certain activities (brain surgery maybe, or nuclear waste disposal) micromanagement can be vitally important.

All of which serves to complicate our search for the secrets of good management. It can be valuable to learn from failure, by flagging up the qualities of management that we find loathsome or ineffectual. However, we have to do it carefully for two reasons: first, because many of the qualities of bad management are actually quite effective when used in moderation and, second, because what demotivates one person can actually be highly motivational for another.

What Makes a Good Manager? Insights from the Survey

When I began working on this book two years ago, I was aware of all these challenges, and I was conscious that there appeared to be many different points of view on what constituted good or bad management. So I decided that it would be a good idea to gather some data of my own, to help me figure out the truth. To stay consistent with the emerging theme of the book, I thought the best people to ask would be employees. Working with colleagues6, I conducted interviews with more than 50 people, asking them about what made their bosses effective or ineffective. Armed with hundreds of pages of interview notes, I then developed a survey, which included a long set of questions about the good and bad things managers do. This was filled in by almost 1000 people across more than 10 companies.

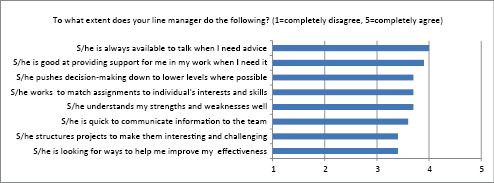

Here are the key findings from the survey. First, I asked the respondents to indicate how much their boss exhibited what we might call the eight good habits of effective managers (see Figure 2.1). Here are the average scores for these eight habits. Top of the list was “always available to talk” and “good at providing support when I need it”; bottom of the list (but still with an average score of more than 3 out of 5) were “structures for projects to make them interesting and challenging” and “looking for ways to help me improve my effectiveness.”

Figure 2.1 Positive Attributes of My Line Manager

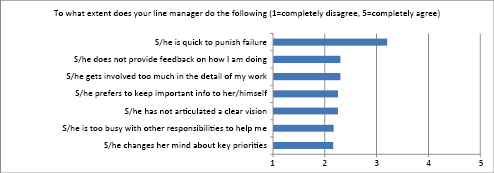

Next, I turned things around, and asked respondents about the seven bad habits that had emerged from the interviews (Figure 2.2). In other words, I wanted to know how much their bosses were engaging in ineffectual management practices – on the basis that we can learn as much from failure as from success. Interestingly, one bad habit stuck out above all the rest with a rating, above the mid-point of three: the boss is “too quick to punish failure.” All the other bad habits rated much lower, between 2.2 and 2.4 on a five-point scale. Notice, also, that by looking at the good habits and bad habits together, we see both sets of behaviors coexisting. For example, the respondents said their bosses were always available and good at providing support, but they also saw quite a lot of evidence that the same bosses were “too busy with other responsibilities to help me” and “do not provide me with feedback on how I am doing.” As I said earlier, management is a messy subject.

Figure 2.2 Negative Attributes of My Line Manager

These charts tell us what the respondents saw their managers doing. Of course, it doesn't tell us much at all about whether these habits were actually effective. I might see my boss making him or herself readily available to give me advice, but if I am happy to work on my own, then I won't value this effort. So to sharpen up the analysis, I asked the respondent a key question: How likely is it that you would recommend your line manager to a colleague, as someone they should work for in the future (1 = not at all, 10 = extremely likely)? I then used statistical analysis to identify which of the good and bad habits listed above were the most important in explaining whether a respondent would recommend his or her manager to others. Table 2.2 lists the results. The ones on the left are the top three things you look for in a manager: when your manager is doing these things, you recommend him or her to your friends as someone they should work for. The ones on the right, on the other hand, are the top three bad habits: when your manager is doing these things, you encourage your friends to find someone else to work for.

Table 2.2 The Most Important Positive and Negative Attributes of a Manager

| Ranked list of “good habits” that predict whether respondents would encourage their friends to work for this manager | Ranked list of “bad habits” that predict whether respondents would discourage their friends from working for this manager |

|---|---|

| 1. S/he is good at providing support for me in my work when I need it | 1. S/he prefers to keep important information to her/himself |

| 2. S/he pushes decision-making down to lower levels wherever possible | 2. S/he has not articulated a clear vision |

| 3. S/he understands my strengths and weaknesses well | 3. S/he is quick to punish failure |

This analysis helped me to close in on what the people filling out the questionnaire thought was really important. The best managers, in their view, are the ones who give their employees space to make decisions, who provide them with support, and who understand what they are capable of. The worst managers, on the other hand, are secretive with information, they don't articulate a clear sense of direction, and they punish failure.

Another Perspective: Insights from Seminar Discussions

These data provided me with a provisional set of conclusions. However, I wanted to try a different approach as well, to see if the same story emerged. So over about 18 months, I incorporated an exercise into my management seminars that I picked up from Henry Stewart, CEO of Happy Ltd. First, I said to them, think back to the last time you were fully engaged and motivated at work; what were the key features of that piece of work? Regardless of whether I was working with a board of directors, front-line employees, high-school teachers, or research scientists, the same points emerged. People were engaged when their work was challenging, when it addressed an important issue, when they had freedom to figure things out for themselves, when they were working with high-quality colleagues, and when they felt their contribution was recognized.

Then I asked them a supplementary question. In the light of this discussion, put on your manager “hat”: what should you do to ensure your employees are fully engaged and motivated? A couple of insights quickly emerged. First, the majority of employees don't want a whole lot of “managing” – they want space, challenge, and opportunity. So the boss has to be thoughtful about when he intervenes and in the type of interventions that he makes. Second, a large part of the manager's job is about structuring the work in advance, so that its importance to the organization is clear, it is sufficiently challenging to get the employee interested, and it allows the employee to work with other good people. Managers also have a coaching and supporting role to play here, providing feedback and resources as needed during the project, and recognition for a job well done afterwards.

There were two frequent grumbles when I did this exercise. Some people felt this approach didn't apply to them. “This is all well and good if you work in new product development,” said one mid-level manufacturing manager, “but my people are sitting on a production line and their work is intrinsically boring. So this model doesn't help me.” My response was, yes, it is much easier to provide your employees with freedom and challenge in some jobs than others, but that doesn't prevent you from looking for creative ways of making production-line work less boring than usual.

The other grumble was that this model was too, well, nice. “Is the best teacher the one who lets his students figure out what they are going to do?” asked one senior airline executive, in a slightly oblique manner. His point, of course, was that good teachers don't just give their students space to figure things out; they also provide very clear targets, they provide instruction, they evaluate their students, and they aren't afraid to hand out failing grades, and to punish them if they fail to show up for class. I am not personally convinced the analogy to high school is a good one (employees and students are motivated by very different things) but, setting that aside, the airline executive was making a good point. The exercise was built on an assumption that employees want to do a good job and they simply need a “context” in which to do it. While this is likely the case for the vast majority of employees, managers still have to have the skills and tools to deal with recalcitrant or ill-equipped employees.

In terms of developing my own point of view on what good management looks like, these were important points. Not all work is intrinsically interesting, so there are limits to how far you can push a model built on employee engagement. And good managers aren't just softies who let their people do what they want – sometimes they have to take tough decisions and make unpopular judgments. Both these points will resurface at various times throughout the book.

The interesting thing, however, in doing this exercise in dozens of management seminars, is how similar the story was to what came out of the large-sample survey. By pulling the insights from the two methodologies together, I ended up with the following five hallmarks of a good manager:

I showed this list to people who had been involved in the research and they confirmed it was a nice summary of what they had intuitively figured out for themselves. But it gradually dawned on me that there was nothing remotely novel or surprising about it. I observed my colleagues at London Business School teaching and I saw them making all the same points. I re-read some recent best-selling business books, such as Dan Pink's Drive and Bob Sutton's Good Boss, Bad Boss, and I went back to some of the classics, such as Peter Drucker's Management and Mary Parker Follet's The New State, and again all the same qualities of good management were there. Then I read about Google's Project Oxygen, as described in the introduction, and how their extensive, data-driven approach had yielded essentially the same set of findings, yet again.

So my search for “what makes a good manager” was over. I had the answer, but so did everyone else. There was no mystery to be solved, no hidden qualities that needed to be uncovered. Perhaps there was no book to be written here after all.

The Rhetoric and The Reality

Rather than give up, I decided to take a different approach. As the old adage has it, “If everyone is thinking the same, that means someone is not thinking.” So if a generation of researchers has all come up with the same advice, but that advice is not being followed, that opens up an opportunity to understand why. So the interesting question is not: What is good management? Rather, the question is: Given that we know what good management is, why on earth don't we do it?

Of course this is not a completely novel question either. In a general sense, there have been lots of studies attempting to close this “knowing doing” gap between what individuals and organizations recognize they should do and what they actually do. It is also called a rhetoric–reality gap or an analysis–execution gap. Moving beyond the field of business, there are entire subdisciplines of psychology and sociology that are focused on helping people to do what they know they should, be it weight loss, giving up smoking, or being a better parent.

Strangely enough, the field management research hasn't really got a good answer to this question yet. For example, a fascinating study undertaken by the Krauthammer Institute revealed enormous gaps between what employees wanted from their managers versus what they actually got7. For example, 89% of respondents wanted their managers to give them autonomy when delegating, but only 28% got this; 74% of respondents wanted their manager to let them finish explaining their idea before interrupting, but only 23% said this is what happened. The gaps here are staggering and, as the study says, “managers continue to display real difficulties on a range of fundamental skills.”

Insights from my own research have also highlighted the size of the gap. Employees want challenging and interesting work to do, but they often get confusing and unclear objectives. They want space to learn and experiment, but they often get a micromanaging and meddling boss who is constantly peering over their shoulder. Table 2.3 lists the five hallmarks of a good manager from earlier, and contrasts it with the more typical behaviors that are exhibited in the workplace.

Table 2.3 What Employees Want and What They Get

| What employees want | What employees often get |

|---|---|

| 1. Challenging work to do | Confusing or unclear objectives “He is unreasonable, he would like everything immediately.” “Goals were blurry, at best; she couldn't prioritize.” |

| 2. Space to work | Micromanagement and meddling “He paid obsessive attention to every single detail. He could not assign the right priorities to tasks. He didn't give a modicum of trust.” |

| 3. Support when needed | A selfish boss, focused on his own agenda “He did not tell us the decisions made during meetings.” “He imposed his own thinking without any explanation.” “He never gave time, said he was too busy, concerned only with his own well-being.” “He was emotionally detached – I came to work in a leg plaster and he didn't even ask what happened to me.” |

| 4. Recognition and praise | Limited and mostly negative feedback “He would wear us down with poisonous remarks and would pick on certain people.” “Lots of shouting and a lack of respect for those around him.” |

| 5. A manager who is not afraid to make tough decisions | A manager who dithers “She couldn't make a decision and always seemed to follow the advice of the last person she spoke to.” |

I often show this chart in seminars and ask the participants why there is so much bad management out there, given that we know what we should be doing. The first few answers are very predictable.

Some people say they don't have time – they are so busy doing other, more important, things that the time and effort required to be an effective manager gets squeezed out. Others say they are being pulled in too many different directions – they would love to carefully structure a project for one of their team, but their own manager keeps changing his mind about what is needed. A third common response is to say how difficult it is to get the right balance – one employee wants very little help, the next wants a lot more, so you have to tailor your approach to the particular needs of each person who works for you.

All of which is true – up to a point. But I simply don't buy the argument that we are “too busy” to implement many of these good management practices. Some of them (recognition and praise, for example) take virtually no time; others (structuring work clearly, for example) take a bit of time but typically save more time later. And of course a great deal of the work many managers spend their time on could – and probably should – be delegated to their employees. In fact, delegation often serves a double purpose – it gives your employees new and often interesting tasks to do and it frees up your time as well.

So I think we need to look beyond these superficial reasons why we don't do what we know we should. We need to dig deeper and to challenge some of our underlying assumptions about what our employees want, and how we and they look at the world. This “employee's eye view” is the subject of the next chapter.

Notes

1 Quotes taken from www.huffingtonpost.com, Margaret Heffernan blog, John Browne's BP Memoir: Not So Much Beyond Business as Beyond Belief, June 7, 2010, and from www.guardian.co.uk, Tom Bower, June 2, 2010.

2 Phil Rosenzweig, The Halo Effect, Pocket Books, 2008.

3 Walter Isaacson, Steve Jobs, Simon & Schuster, 2011, page 124.

4 Fred Goodwin quotes taken from: Hancock, M. and Zahawi, N., Masters of Nothing, Biteback Publishing, 2011, page 167, www.ianfraser.org; The Times, February 2009. Steve Jobs quotes taken from Isaacson, 2011, op cit. The odd numbered quotes are about Goodwin, the even numbered ones are about Jobs.

5 Isaacson, 2011, op cit, page 112.

6 The colleagues who helped me here were Lisa Duke, Stefano Turconi, and Vyla Rollins.

7 The Krauthammer Observatory: Time for the yearly performance review … of our managers! Steffi Gande, Issue 4, 2010, www.krauthammer.com.