3

Getting inside the Minds of Your Employees: What Makes them Tick?

Do you think you understand your employees? Do you pride yourself on your empathy and your insight into what makes them tick? Most of us would like to answer yes to these questions, but the evidence says that we would be wrong to do so.

Consider the example of Mike, a senior HR manager at an auto parts factory in the north of England. He had been drafted in from the US parent company, Motor Co, to help implement a new set of manufacturing practices, but after a year he was pulling his hair out: “Coming here has been a nightmare and a complete career disaster,” was his exasperated comment, “this is one of the most militant shops I've ever seen, but none of it's union activity.”

Mike's experiences are recounted in a fascinating study by three UK academics, Mahmoud Ezzamel, Hugh Wilmott, and Frank Worthington, called “Power, control and resistance in ‘the factory that time forgot’.1” It is a story of an old-fashioned British firm, Northern Plant, with manufacturing practices “at least ten years behind the times.” Its workers were clever, but suspicious of change. They understood what was possible far better than the plant's managers, and as a result the managers would tolerate what games the workers played, as long as production levels were maintained.

Into this mix came Mike and his American colleagues, following the acquisition by Motor Co. All sorts of modern work practices, from Toyota-style lean production through to cellular manufacturing, were brought over. For Mike, these were proven practices that would benefit the plant workers as well as providing efficiency gains. However, for the old hands at Northern Plant, they were an unwelcome intrusion into their established order.

The workers were too savvy to actively resist the new practices. Instead, they responded with what the researchers called “sustained yet overtly accommodating resistance.” They delayed the creation of work teams by arguing about how they should be put together, they challenged the new performance metrics for not being valid, and they spread disharmony among the managers by showing how they had been stabbing each other in the back. Worst of all, these various tactics for resisting change were not consistent across the factory. Mike, the American HR professional, was used to formal union activity and he had experience in dealing with it, but he had no idea how to cope with this form of “disorganized resistance.2”

Getting inside the Mind of The Employee

So what is the point of this slightly quaint tale of scheming, intransigent workers and impotent managers? Obviously Northern Plant is not a typical factory and it is rare for managers to find themselves in Mike's shoes, dropped into an alien world with few familiar reference points.

However, most of us have had occasional Mike-like experiences, where we have struggled to understand our employees' behavior. I recall an instance when I had just taken on my first proper managerial job. I was full of bright ideas for changes we could make. I sent an email out to my team, suggesting a complete rethinking of the structure of the team and how I wanted their input in the redesign. The response was complete silence: no-one replied to the email and no-one mentioned it in the next daily catch-up meeting either. I knew I had done something wrong, but I had no idea what. Eventually, after some prompting from me, the most senior person in the team gave me some advice: “Your ideas are too radical for this team; some of them are very risk-averse. They need to get to know you properly before you start a conversation like this.” Suitably chastened, I resolved to be a bit more thoughtful before proposing my next bright idea – and to get to know my team better.

This chapter is a “deep dive” into the mind of the employee, to shed some light on what makes him or her tick? Two cautionary notes before we get started. First, it is difficult to write about the employee without sounding a little bit patronizing. This is not my intention. Rather, I will attempt to stand back a little and to adopt an analytical approach. The subsequent chapters (Chapters 4 through 6) will provide plenty of practical advice, but this chapter will be a bit more academic in its tone.

Second, my bias in this chapter will be towards understanding employees in poorly paid, tedious jobs, where the contrast between the attitude of the boss and employee is typically the greatest. Some managers have never experienced such jobs; others started their careers in this sort of work but have forgotten what it felt like. Either way, these are the jobs where the worldview of the employee is hardest for a seasoned manager to relate to. Of course, the sceptical reader will also note that I, as an academic, may also find it hard to get my head inside the worldview of an employee in a poorly paid, tedious job. Fair enough. So to prepare for this chapter, I spent a lot of time interviewing and working with front-line employees, in a hotel chain, a call center, a mining company, and a building company. I also developed a questionnaire to get their perspectives, filled out by almost 1000 people.

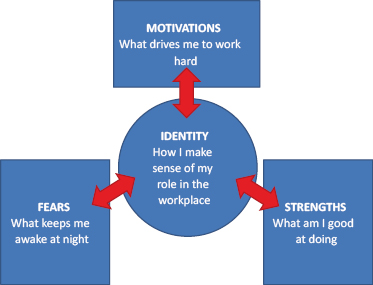

The chapter looks at four aspects of the employee's worldview: motivations, fears, strengths, and identity (Figure 3.1).

Figure 3.1 Four Aspects of the Employee's Worldview

Identity

Let's start with identity, because it is the most central, as well as the most puzzling, part of the story. If we go back to the workers at Northern Plant, their behavior didn't make much sense from Mike's corporate viewpoint. After all, the new practices he was trying to implement were going to make the plant more productive (thereby safeguarding jobs) and they were supposed to help workers develop broader skillsets and become more involved in their work. Unfortunately, the workers didn't see it that way – what they saw was a threat to the identity they had developed for themselves over many years. A central part of this identity was autonomy, that is, the freedom to sort out their own problems as long as they hit their production targets. New management practices of Motor Co threatened this autonomy – it required workers to buy in to new practices and new measures that they would not have control over. So the most natural way of retaining their self-identity was to push back – to use whatever tricks and techniques they could muster to keep the new practices at bay. The importance of retaining a clear sense of identity was, somewhat surprisingly, more important than concerns for the long-term viability of the plant.

So the first big insight for you as a manager is that you need to get to grips with your employees self-identity: how they see their role in the workplace. The trouble is, identity is a slippery thing. An employee's identity evolves over time, as a function of his or her experiences, responsibilities, and relationships. Most people don't actually take the time to articulate – even to themselves – what their identity is. There are some simple stereotypes that we can quickly recognize: the ambitious MBA graduate who will do whatever it takes to climb the corporate ladder; the high-school teacher who loves helping kids learn; or the immigrant who works two minimum-wage jobs to pay for his or her kid's education. These individuals have no trouble making sense of their role in the workplace. But for the vast majority of employees, identity is much more fuzzy and open to interpretation.

Understanding the self-identity of your employees therefore requires a certain amount of detective work. There is no simple categorization scheme you can use, so you have to divine how workers see themselves by observing their reaction to changes in their working environment. Here is another example drawn from an academic research study3, a story about the introduction of self-managed teams in Stitchco, a UK clothing manufacturer, in the 1990s. As with Northern Plant, the logic of shifting from an old-fashioned piecework system to a new team-based production system seemed entirely obvious to top management, as it would help the factory to increase its output, while also providing workers with a broader range of skills. By providing a base rate of pay and team-based incentives, they believed the new system would also make the workers financially better off.

However, the mostly-female workforce hated the change. The more experienced workers found themselves carrying the newer ones and working harder than before in order to reach their team bonus targets. Some of them were asked to become supervisors, but they found it hard to start telling their co-workers what to do. Many of them liked to be able to set their own pace, perhaps working harder one day and more slowly the next day, and the team-based system made this much harder to do.

Again, a well-intentioned change hit resistance because management failed to understand the self-identity of the workforce. In this case, the female employees at Stitchco were operating in very narrowly defined jobs with no autonomy over what they did. But they did have control over one important part of their work, namely the speed with which they worked. They also enjoyed the banter of the shopfloor, being mates with their fellow machinists. The teamwork model threatened both these features – some women found themselves overseeing their mates, which created tension, while others resented having to worry about the bonuses of their mates in deciding how fast to work.

Management at Stitchco gradually got their heads around these problems, and while they didn't get rid of the teamwork system altogether they scaled back some elements, for example, by providing supervisors rather than forcing the women on the shopfloor to assume these roles. Performance in the factory gradually improved, though not as quickly as top management would have liked.

So what's the bottom line here? Simply that all employees have a way of making sense of the things they do and why they do them, and that it is much easier to get things done when you reinforce, rather than challenge, this sense of identity. Good managers are detectives – they look for clues about which initiatives their employees get excited about and which ones they resist, and they gradually build up a picture of their employees' identity.

Motivations

Motivation is the condition in an employee that activates his or her behavior and gives it direction; it is what drives the employee to spend time and energy on a particular task or goal. Unlike identity, which is poorly understood and rarely discussed, motivation is a topic of which every manager has at least a basic understanding4.

Employees are motivated by an enormous range of things. In an earlier book, I distinguished between three drivers of discretionary effort from employees:

- Material drivers, including salary, bonuses, promotions, and prizes

- Social drivers, including recognition for achievement, status, and having good colleagues

- Personal drivers, including freedom to act, the opportunity to build expertise, and working for a worthwhile cause

While all of these drivers matter, they are not equally important. It has been shown, for example, that materials drivers (also called extrinsic rewards) have very little influence over a certain threshold level, whereas social and personal drivers (intrinsic rewards) can be extremely powerful at all levels. Material drivers are also known to crowd out other drivers – give an investment banker the promise of a large bonus and all other things get ignored.

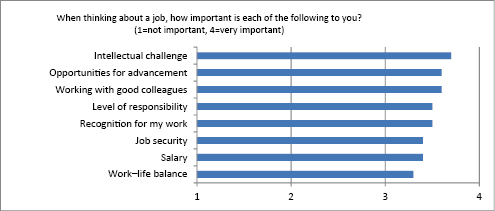

As part of my research for this book, I polled almost 1000 employees to ask about the importance of various sources of motivation. Figure 3.2 shows the overall scores. True to expectation, employees say that the most important things for them in a job are intellectual challenge, opportunities for advancement, and working for good colleagues. Salary, as usual, is seen as relatively unimportant compared to these personal and social drivers.

Figure 3.2 What Motivates Employees?

These findings echo the story from the last chapter. Good managers, you will recall, provide their employees with challenging work, space to act, support when needed, and recognition. Not surprisingly, these are the very same features that employees seek in their work. Many other studies have come up with similar findings.

However, this isn't the whole story. I have always had a nagging concern that this emphasis on intellectual challenge and personal advancement is a little, well, idealistic. We know from Maslow's famous Hierarchy of Needs that such higher-order needs are only valid once someone has covered all their more basic needs. And what if these findings were nothing more than a reflection of our own values and biases as researchers? After presenting these ideas a couple of years ago, an executive we will call John came up to me: “This is good stuff, Julian, but you are looking at the wrong people. You should be studying people with shit jobs. That is where the real challenge lies.”

John had hit upon an important point. When you look at the full spectrum of jobs in the economy, the ones with intrinsically high levels of satisfaction are few in number (see Box 3.1: Job Satisfaction versus Pay). It is relatively easy, as a manager, to end up with happy and engaged employees when they are doing work they might choose as a hobby. It is also relatively easy to devise motivation schemes when there are opportunities for large salary increments and bonuses. The challenging jobs, from a managers' perspective, are the ones with low pay and low intrinsic satisfaction – things like burger flipping, hotel room cleaning, or working on a production line or in a call center.

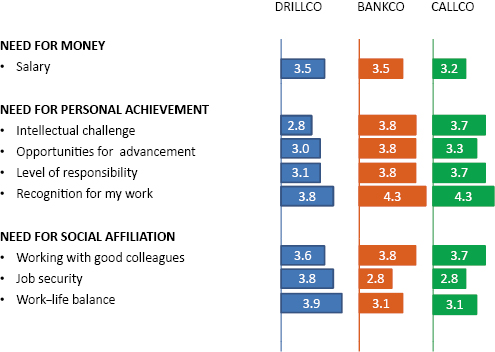

So what are the motivators for people working in these types of jobs? Here is one simple piece of analysis. From my survey, I extracted the average scores for three companies. Drill Co is a mining company, and the respondents were front-line employees in a basic processing operation. Call Co is an IT services company and the respondents were call center workers. In other words, both groups were in John's category of “shit jobs.” For the sake of contrast, Bank Co is a financial services company and the respondents were recent MBA graduates in white-collar jobs with good promotion prospects.

The differences in scores across the three companies are significant (see Figure 3.3). In my interpretation, Drill Co's employees are stuck in a job with few prospects for growth or promotion, so they don't waste their energy worrying about those things. They value recognition for a job well done, but their highest motivators are for the various aspects of social affiliation – working with good colleagues, job security, and work–life balance. Their identity, rather like the people at Northern Plant, is wrapped up in their colleagues and the community in which they are working. Bank Co's employees, on the other extreme, are ambitious and eager to please. They have a very high need for personal achievement – because they know it can be accommodated in this company – and they have much less concern for job security and work–life balance at this point in their working lives. Call Co's employees, despite being in poorly paid and tedious jobs, are actually more like Bank Co's employees in terms of what motivates them. This might appear surprising, but one important reason is that the company is growing quickly, so there are many promotion opportunities.

Figure 3.3 Motivation Levels in Three Different Companies

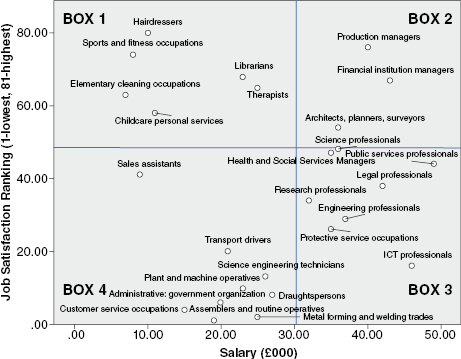

Not all jobs were created equally when it comes to motivation. I dug into the statistics on employment across the UK and this allowed me to put together a chart comparing the average salary and job satisfaction level for every job category in the country (Figure 3.4)6. If we simply divide this chart into four boxes, we get the following results. Box 1 is the people whose hobby is also their job – the hairdressers, vicars, and fitness trainers. They aren't well paid, but they love what they do so they aren't so bothered about money. Box 2 is the well-paid and highly satisfied group, often professionals such as architects, scientists, or senior executives. Box 3 is the well-paid but unsatisfied group, which includes many subsectors of the IT industry, commissioned salespeople, and the lower levels of professional hierarchies such as law, accountancy, and banking. As an academic working in a business school, I have plenty of friends in each of these boxes, and I can easily make sense of their motivations, aspirations, and concerns.

Figure 3.4 UK Jobs Rated by Job Satisfaction and Average Salary

Box 4 is perhaps the most important one. Working in a factory or call center or hotel or McDonalds is poorly paid work, and not a whole lot of fun, and of course there are far more people, in absolute numbers, working in Box 4 than any of the other boxes. If we are concerned about the societal benefits of improving the quality of management, as discussed in Chapter 1, then this is the biggest opportunity area. It is also the biggest challenge: when employees are intrinsically motivated (Box 1) or their extrinsic rewards are high (Box 3), the “levers” the manager can pull to get more out of them are pretty well understood, but motivating employees when their work is neither intrinsically or extrinsically satisfying is far from straightforward.

These data provide us with a slightly more nuanced view of employee motivation. Yes, it is true that employees are motivated by work that gives them a sense of purpose, freedom to make mistakes, and opportunities to develop, but there are a great many jobs where these features are simply not available. In such cases, employees are pragmatic and flexible. They don't yearn for things that aren't on offer; instead, they focus on those aspects of their working lives that they have some control over, and they seek to make improvements there5.

For example, I found myself working on the front desk in a hotel chain in London, in the Summer of 2011, alongside two thirty-something Romanian immigrants. They were articulate, thoughtful women, one with a degree in Accounting, both with children, and they were broadly happy with their work, despite the minimum-wage pay scale. I asked them about why they did this work and what motivated them. They didn't linger on the need for intellectual challenge in their work or the importance of responsibility over others. Instead, their answers focused on the opportunities to do overtime, the training courses on offer, the quality of their colleagues, and the opportunity to bring their children up in London. These were all motivators, in other words, that were within reach. These women had scaled back their ambitions in certain areas and shifted their ambitions to match the identity that they had taken on in the workplace.

In sum, employees are motivated by a complex set of factors. As a manager, it is important to understand the near-universal desire for challenging, autonomous work that allows an individual to develop their skills. But it is also important to look more closely at the specific circumstances the employees find themselves in, because those circumstances will lead some motivators to be enhanced and others suppressed.

Fears

Compared to motivation, fear gets much less attention in studies of the workplace. And yet it is perhaps an equally important driver of behavior. One employee I interviewed for this book described his organization as follows: “We live in a culture of fear, we keep our heads down, trying to avoid doing anything to upset [the boss]. Sometimes everything is fine, but then he will blow up at someone because they made a copying mistake, and the whole office is affected.” I talked in the previous chapter about the “seven deadly sins” of management and how poisonous an angry or greedy boss can be for the rest of the organization. But even in a relatively well-managed workplace, there is still a lot of fear under the surface – fear of looking foolish when you make a presentation, fear of not performing up to expectations, fear of losing your job if the company gets into trouble.

Quality guru Edwards Deming was one writer who picked up on the importance of fear. In his famous list of 14 principles, number 8 was the need to Drive out Fear in the workplace7. “No-one can put in his best performance unless he feels secure,” Deming wrote, “and secure means without fear, not afraid to express ideas, not afraid to ask questions.”

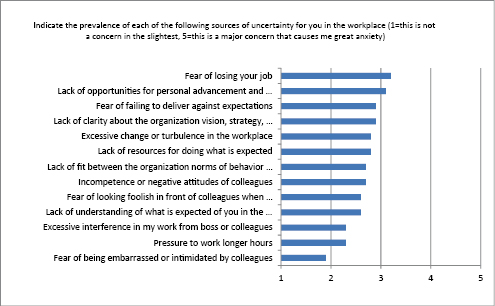

So what are manifestations of fear in the workplace? In doing the research for this book, I drew up a list of 14 potential sources of fear and put them into my survey. The chart in Figure 3.5 lists them in order.

Figure 3.5 Sources of Fear in the Workplace

I discussed these fears with many of my interview subjects. What became apparent, very quickly, was the enormous diversity of answers to my question “What is your biggest fear or concern?” One person said her biggest concern was not being able to pay her team the size of bonuses they were expecting (yes, she was a banker); another was worried about the stress he was under because of the long hours required in his job; a third was worried about a rumoured downsizing and the possibility that he might lose his job.

I quickly realized that what counts as fear depends on the situation the employee is in. Some people were focused on very basic fears, such as losing their job, others had what we might call higher-order concerns, such as not living up to their own expectations, or not getting the level of mentoring they would like.

This insight then led to the concept of a “Hierarchy of Fears” in organizations that mirrors Abraham Maslow's famous “Hierarchy of Needs.” Thus, the basic fear of losing one's job is analogous to the need for food and shelter; then once this fear has been alleviated, other fears or concerns, such as not fitting in as well as one might like or not getting the personal development opportunities one craves, start to surface. The four levels can be described as follows:

- Level 1: need for security and safety in the workplace. This need manifests itself primarily in a fear of redundancy: “My major concern is about the future of this company: once this project finishes, I am not sure what I would end up doing.” A related fear is concern with excessive turbulence and change: “My biggest fears are that our company is understaffed, that as we move ahead we find ourselves unprepared to deal with such a huge amount of work.”

- Level 2: need for affiliation to a group. This need is linked to two fears. One is a concern about not fitting in. “I find the forced agreeableness of the culture disturbing, I am not good at this,” said one person. “The things I work on and see as strategic priorities do not match what the company sees as a priority,” said another. The other is what we might call a frustration with ineffective processes, in that they compromise the quality of the working environment. “What demotivates me is poor organization of work … sometimes the company is excessively bureaucratic, which slows the work-flow down significantly,” was one person's biggest concern. Another said, “I am worried that we spend a lot of time firefighting and doing dismal time-wasting projects.”

- Level 3: need for personal achievement. This need links to several fears. One is a fear of failing to deliver on high expectation: “One of my biggest anxieties is about assignments not completely finished.” The second is a fear of looking incompetent. “I worry about looking stupid in front of others, of not performing,” was one person's biggest fear. The third is a concern with the stress of work, in that stress is typically a by-product of working hard and setting high expectations. One person described it thus: “The worst aspect of my job is the stress that derives from the unpredictability of the workload. … I think such tensions cascade down from the top.”

- Level 4: need for self-actualization. This need links to a concern about the lack of opportunities for personal development. “My current role is too limited in scope, it doesn't utilize my broader skillset … my line manager is in another location, which affects my career progression” and “I am worried my boss [who is an excellent mentor] may leave” were two typical comments here.

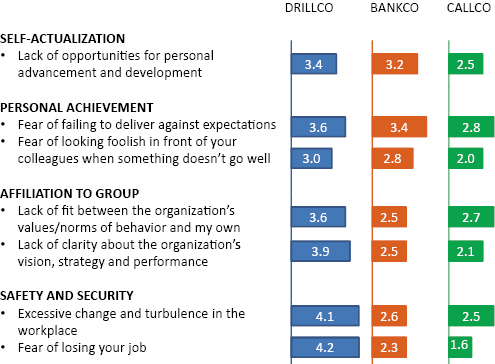

So how can you make use of this hierarchy of fears? Again, it is useful to compare the answers given in three of the companies in my research to see how they vary (see Figure 3.6). At Drill Co (the mining company), there is a high level of angst among the employees. Their scores are higher than average across the board but, more importantly, their fears are highest at “Level 1” in the hierarchy. Put simply, they are worried about their jobs, because the company is in a very precarious position, and this means that all the higher-order concerns about affiliation, personal achievement, and self-actualization are just not that important. As a manager at Drill Co, you would want to resolve these basic fears as soon as possible, and you wouldn't want to invest a great deal of effort on the higher-order concerns until you had done so.

Figure 3.6 Fears and Uncertainties in Three Companies

Bank Co (the financial services company) is in a very different position. The biggest concerns its employees have are failing to deliver against expectations and lack of opportunities for personal development and growth. The ratings for fears at the lower level of the hierarchy are significantly lower. It is easy to make sense of this story, as Bank Co is full of ambitious, young employees who feel secure in their work (and their ability to get another job if this one doesn't pan out), so are worried only about the higher-order parts of the hierarchy. As a manager at Bank Co, your time is likely to be spent coaching and supporting these individuals to help them achieve their potential, and assuring the best ones that this company will help them develop further.

Call Co (the call center operator) has a more balanced profile than the other two and seems to be a relatively worry-free place, with ratings lower than average across the board. The biggest concerns are a fear of failing to deliver and a concern about lack of fit with the company's norms, but taken as a whole there are very few “red flags” here. As a manager at Call Co, you would want to invest some time on cultural issues, making sure employees understood what was expected of them, and on coaching and supporting the people who are looking for bigger responsibilities.

By profiling your employees' fears and concerns in this way, you can draw some useful inferences about how to prioritize your efforts as a manager. Of course it's worth remembering that every individual has a slightly different set of concerns – these are aggregate figures that obscure as much as they reveal.

It is also worth keeping in mind that the hierarchy of fears applies only to the workplace, and work is only one part of an individual's life. Some people seek to satisfy most of their needs through work; others rely on their family and their nonwork activities to address the various elements of Maslow's pyramid. For example, many people choose to start their own business to achieve esteem and self-actualization, but of course without any job security. In such cases, they derive their security from other sources, typically a supportive family. So the workplace cannot satisfy all an employee's needs, but we believe it has the potential to satisfy many of them. It is up to us, as managers, to decide how many of the elements of the hierarchy of needs we want to satisfy for our employees.

Strengths

The final part of the framework for making sense of the employee's worldview is strengths – or more broadly the things an individual does well, or less well, in the workplace. It has become fashionable to talk about strengths largely thanks to Marcus Buckingham's influential research8. He has observed that as employees and as managers we spend a lot of time – too much time – identifying and working on our weaknesses. It is human nature, he observes, to pick out the worst grade in a report card and to try to improve it, but it is the wrong response. First, we will never take our weaknesses and turn them into strengths; second, life is too short to spend all our time working on things we are not very good at. Instead, we should figure out what our strengths are and we should play to them – we should build them up further and we should find work opportunities that allow us to use them to the fullest. For companies, the challenge is to build a better fit between employees' strengths and the jobs they do. For example, rather than define jobs first and fill them with suitable people, we should start with our people and design jobs around their proven strengths.

Many companies have worked with Marcus Buckingham's “strengthfinder” methodology and some have developed them further. For example, HCL Technologies, the Indian IT services company, has a tool called EPIC – Employee Passion Indicative Count – which it uses to track the aspects of an employee's work that he is passionate about (I will describe this in more detail in Chapter 4). This analysis helps managers to place their team members into the appropriate jobs, and even to help employees shape their own roles.

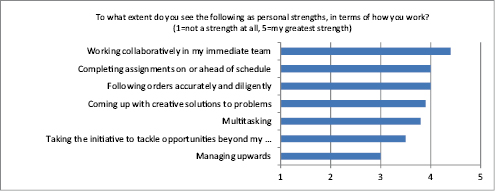

During the research for this book I was drawn to the idea that we should take employee's strengths more seriously, so in my survey I asked the respondents about how good they were at various aspects of their work. Their responses are given in Figure 3.7.

Figure 3.7 Employee Strengths in the Workplace

I must admit, I found these ratings rather puzzling when I first saw them. It is no surprise really that people rated themselves as above average on everything – it is well known that people tend to have an overly rosy picture of their own capabilities, whether it is driving a car or relating to others. But it was surprising to see how positively people evaluated themselves on some of the specific activities. Most people, for example, thought “working collaboratively in my immediate team” was something they did better than completing assignments on schedule or following orders, despite the fact that effective collaboration is really hard to do and has been shown to be a weakness for many people. Many people said they were good at “coming up with creative solutions,” which also flies in the face of evidence for a lack of creativity in large organizations.

So at first glance, these findings suggested the respondents were, at very least, putting a very positive spin on their strengths. They were perhaps focusing on what they would like to be good at, rather than what they were objectively good at. I dug deeper and the story became even more disconcerting. First, I looked for significant variations across companies, age, gender, and so forth, but there were no meaningful patterns. This was very “noisy” data. Next, I compared the ratings these individuals had given themselves and then (for a subsample of 50) I got their own managers to rate them on the same strengths. When I compared the two sets of numbers, I found there was no significant correlation between them. In other words, the things the employees said they were good at did not match up with what their managers thought they were good at. It is impossible to say who is right and who is wrong here, but the bottom line is that there is a substantial perception gap when it comes to evaluating employee strengths. This again is a finding that other researchers have confirmed9.

My simple conclusion from this analysis is that most of us don't actually know what we are good at. Partly, this is because we have no solid bases of comparison. Apart from a few activities where there are hard data (e.g. teaching ratings at a university), most of what we do in the workplace is highly open to interpretation. Partly we are also happy to delude ourselves – we talk up our skills in certain desirable areas and we ignore evidence that doesn't fit with our own self-image. As with motivation and fear, the employee's perceptions of his or her strengths are tightly linked to identity.

Career guidance counsellors have known this for years. When mid-career people seek professional advice on what they should do next, it is often because they have a nagging feeling that they have missed their calling in life. However, “calling” is entirely the wrong word. It is rare for someone to have a sufficiently clear sense of what he is good at, and what various careers offer, that he is able to make a straight match. More often, he will jump from job to job, trying each one out for size and looking for the signs that he is getting closer to a good fit. Career counsellors will always ask their clients to evaluate their strengths using the various profiling tools on offer, but they will also use lateral techniques to help their clients know themselves better. When are you at your happiest? When are you most miserable? Who do you envy and why?10

As with other aspects of the employee's worldview, managers often have to work pretty hard to divine what their employees' real strengths are. It's not that the employee is being modest or reserved when he doesn't give you a straight answer; more likely, he simply hasn't figured it out himself yet.

I think a significant part of what is happening here that is many employees haven't taken the time to think actively about these things. Consider two interviews I conducted during the research. The first was with Harry, a front-line employee in a call center. I asked him to describe his work and what his strengths were. The answer was: “When customers call, I help them solve their problems. I know the software really well, so I can usually fix their problems pretty quickly. And that's it.” I asked about his manager, what he did well, what he could do differently, and the reply was “Well, he is very open, I think, and he does a good job.” Harry was a smart guy, no question, but it was clear he hadn't invested any of his intellectual energy in theorizing about his work or about what good management looked like.

The next interview was with Linus, a barman in a hotel. He had just been promoted to head barman, which meant he had a couple of guys reporting to him, and he was responsible for the takings every evening. The same questions led to a much more lively conversation. Linus had a clear view of which parts of the job he was good at, which needed work, and he had a pretty articulate story about his manager's style of working – very direct, no uncertainty about what was needed, but a bit too controlling. In exploring these issues with Linus, it became clear that he had recently made the shift from being managed, which is a passive role, to managing two other people, an active role. He had had to figure out what being a manager meant and this new responsibility suddenly made a lot of his boss' actions more meaningful to him.

What's the bottom line here for you as a manager? Again, some similar themes come out. First, don't assume your employees have a good sense of their real strengths and weaknesses. Sure, they will have some views, but they will be a mix of firmly held convictions (“I am hopeless at public speaking”) and more lightly held hypotheses (“I think I am a good team player”). It is a worthwhile, though sometimes painful, exercise to compare your evaluations of their strengths against their own, to try to get a better fix on where they should focus their energies in the future.

Second, it's much easier to be a good employee if you are also someone else's boss. The beauty of a hierarchical system (except for those right at the bottom or right at the top) is that we are managing up and down at the same time. We can improve the way we manage our employees by learning from the way our boss manages us and we can improve the way we manage our boss by learning from the way we manage our own employees.

So What does an Employee's Eye-View Tell us?

It can be quite heavy going trying to get inside the heads of your employees, and maybe that is one reason we don't spend much time doing it. There are some pretty obvious points that emerge from this discussion. There are enormous variations in how employees see the world and what their motivations, fears, and strengths are. Their outlook is often very different from that of their managers. Many of them are selling their time for labour, nothing more, and so they haven't invested any emotional energy in understanding the company's wider objectives or plans.

However, there are also some important and surprising insights. Employees often resist what seem to be well-intentioned proposals, and understanding why, in terms of the threat these proposals bring to the employee's self-image, is useful. Making sense of employee fears in terms of Maslow's hierarchy of needs is also potentially quite powerful as a diagnostic device.

Let me summarize the chapter with four observations about your employees:

- They have an implicit self-identity that shapes their behavior. Identity is the way people look at themselves. They prefer to take actions that are consistent with and reinforce their identity. They resist initiatives that threaten or impugn that identity.

- They don't have a great deal of interest in or concern for the company as a whole. This doesn't mean they are necessarily negative towards the company, but indifference is common. Moreover, such employees often lack the interest to articulate what might make their work more interesting.

- There is often a lurking cynicism, especially when change programs are introduced. By cynicism I mean a tendency to frame interventions from above in a negative way. Cynicism ranges from shopfloor banter (“another crazy idea from management”) through to poisonous and malicious gossip (“they are only doing this to feather their own nests”). Cynicism is essentially a defence mechanism, and the more often things have gone wrong in the past, the more likely employees are to be wary and guarded next time.

- Yet despite all this, most employees are not wanting for intellectual or creative skills. It's just that those skills are being parlayed into opportunities outside their working lives. It is easy to fall into patronizing behavior as a manager, but you do so at your peril.

These characteristics are not uniformly spread across all employees. They are more likely to be seen in certain working environments than others. For example, they are more likely to be true when workers are older, have longer tenure, are unionized, are surrounded by people like themselves, and are operating in a mature industry – Northern Plant and Stitchco being classic examples. They are less likely to be true with a younger and more diverse labor force and in a fast-growing industry where there are lots of opportunities for people to get promoted.

While it is important to understand how your employees look at the world, it is even more important to figure out how to use these insights. In the next chapter, we will turn our attention back to your role as a manager and to the question of how you can help your employees do their best work.

Notes

1 Ezzamel, M., Wilmott, H., and Worthington, F., Power, control and resistance in “the factory that time forgot,” Journal of Management Studies, 2001, 38(8): 1053–1079.

2 Unfortunately, the story of Northern Plant does not have a neat and tidy conclusion. Mike did not sack all the recalcitrant workers, nor did he win them all over. He and his colleagues continued to push the new management practices and workers continued to find ways of pushing back. The researchers concluded that “notwithstanding the changes in the technical organization of production that occurred, there had been little substantive change in the social organization of production.”

3 Ezzamel, M. and Wilmott, H., Accounting for teamwork: a critical study of group-based systems of organizational control, Administrative Science Quarterly, 1998, 43: 358–396. Also see: Jenkins, S. and Delbridge, R., Disconnected workplaces: interests and identities in the “High Performance Factory,” in Searching for the H in HRM (eds S. Bolton and M. Houlihan), Palgrave Macmillan, Basingstoke, 2007.

4 See, for example: Ryan, R.M. and Deci, E.L., Self-determination theory and the facilitation of intrinsic motivation, social development, and well-being, American Psychologist, 2000, 55(1): 68–87; MacGregor, D., The Human Side of Enterprise, Irwin/McGraw-Hill, New York, 1960; Herzberg, F., The Motivation to Work, John Wiley & Sons, Inc., New York, 1959. For a more practical slant on these topics, see Pink, D., Drive, Riverhead Books, New York, 2009.

5 This point is developed in a detailed academic study: Gruenberg, B., The Happy Worker: an analysis of educational and occupational differences in determinants of job satisfaction, American Journal of Sociology, 1980, 86(2): 247–270.

6 These data were taken from the UK Office of National Statistics. The job satisfaction data come from www.bath.ac.uk/news/pdf/rose-table.pdf. The job pay data come from http://www.ons.gov.uk/ons/rel/ashe/annual-survey-of-hours-and-earnings/ashe-results-2011/ashe-statistical-bulletin-2011.html.

7 Deming, E., Out of the Crisis, MIT Press, 1968.

8 For example: Buckingham, M. and Clifton, D., Now Discover Your Strengths, Simon & Schuster UK, 2004.

9 Gibson, C., Cooper, C., and Conger, J.A., Do you see what we see? The complex effects of perceptual distance between leaders and teams, Journal of Applied Psychology, 2009, 94(1): 62–76.

10 For a practical example of this, see De Botton, A., The Pleasures and Sorrows of Work, Hamish Hamilton, 2009.