6

Experimentation: Functioning in a Broken System

Have you ever tried anything a bit risky in your company: an idea that no-one had pushed before or a project that required people across the company to act in new ways? If you have, you probably felt you succeeded despite the system rather than because of it. Rather than help you in your endeavor, the people and processes surrounding you conspired to hold you back, and it was only through tenacity and resolve that you were able to prevail.

I have quite a lot of personal experience of how this happens and I have observed dozens of similar cases through my research. It is easy to conclude that the “system” in large organizations is broken. However, this is only half true. Large organizations do indeed suffer from acute limitations and bizarre pathologies, but they also have enormous strengths that we should not lose sight of. Being an effective manager requires a deep understanding of the limitations and strengths of the organization in which you are working.

Here is a cautionary tale from my own experience. I once agreed to do a Webinar for a big organization. I have done half-a-dozen Webinars before, typically for small companies trying to get people to pay for online content. In these cases, the process looks like this: they email me, I agree to do it, we arrange a date 2–3 months out, we do a quick technology check the week before, and then the event happens. It is all very easy, lecturing to an unseen audience in my own office. Frankly, I sometimes wonder how many people are actually listening. But that is a separate issue.

The process with this particular organization was rather different. The person I was talking to suggested a multispeaker event six months out. The other speakers and I all said yes. He then consulted with his board, who decided it was all a bit rushed, and couldn't be marketed properly, so we ended up delaying by a further six months. We all agreed.

A couple of months later I received the draft contract, 10 pages of detailed legalese, including clauses restricting my use of the presentation materials with other audiences, and requiring me to acknowledge them in all subsequent use of the materials. At which point it finally dawned on me what was going on – the Webinar was being treated like a book, one of those bulky paper things we used to take on holiday with us before the Kindle was invented. Once I had taken out the clauses that restricted my use of my own materials, the final version was then sent to me in hardcopy, by courier – one of those companies that was set up to distribute paper around the world before the Internet was invented.

The company had, in other words, taken its century-old process for selection and negotiating rights and applied it with little adjustment to these new digital and virtual offerings. My realization that this is what happened also explained the mystery around the six-month delay. Every publisher knows that books either get published in spring or fall; that is the way the publishing calendar works. So once our Webinar missed the spring window, it obviously had to be bumped to an autumn date.

I know I am being a bit harsh on the organization here. The people who work there are smart and knowledgeable and they understand these new technologies as well as I do. But they are being held hostage by their archaic management processes, processes that they themselves curse but are incapable of getting around. The net result, in this particular case, was a Webinar that cost a great deal to put on (in management time and legal fees) and with significant delays. When the event finally happened it went fine, but the size of the audience and the quality of the product were no better or worse than the low-cost, no-frills Webinars I had done before.

Understanding Bureaucracy – and Rising Above It

This experience reinforced for me just how inert and inflexible management processes are in most large organizations. A company can change its strategy, replace all its senior managers, outsource half its activities, and even get people thinking differently, but its core management processes – the way it allocates resources, evaluates people, negotiates contracts – will still be running under their own steam, just as they did decades earlier.

Management processes are the embodiment of an organization principle known as bureaucracy. We all know the word, and we often use it as a shorthand for everything that is bad about large organizations. Strangely, though, the original meaning of bureaucracy was entirely positive. German sociologist Max Weber brought the term into regular usage. He said organizations could coordinate activity in one of three ways: by using the traditional beliefs and norms of what had always been done (“traditional” domination); by relying on the personality of their leader (“charismatic” domination); or by developing a system of rules and procedures that transcended the idiosyncrasies of a particular person or situation (“legal” domination). This third model, which came to be known as bureaucracy, dominated the business world during the twentieth century, and was indeed very effective as a means of generating efficiency and creating outputs with consistent quality.

However, bureaucratic systems also have their limitations. They create a high level of alienation and disengagement among employees. They allow people to exercise their power in ways that subvert the organization's broader goals. They also breed management processes that take on a life of their own and never die out. At their worst, bureaucratic organizations are made up of unhappy employees, Machiavellian managers, and internally focused processes where no-one can see the forest for the trees.

What can we do to overcome these deep pathologies? One way forward is to attempt to make organizations less bureaucratic. If you have ever picked up a book by Tom Peters, Rosabeth Moss Kanter, or Gary Hamel, you will have seen plenty of advice on how to de-bureaucratize the business world, such as pushing greater front-line accountability, eliminating mid-management roles, encouraging spin-offs, and so on. These are all sensible suggestions but they don't “solve” the problems of bureaucracy, they simply keep them under control.

The other way forward, and my focus here, is for individuals to find more effective ways of working within this “broken” system. In other words, as a manager, you learn to accept that the system has certain limits, and you make sufficient changes within your sphere of influence to get things done. For example, in one research project I was involved in, the evidence showed clearly that the more complex the system, the more important it was for individuals to be multitasking, proactive types who were able to “rise above the nonsense” to make things happen.

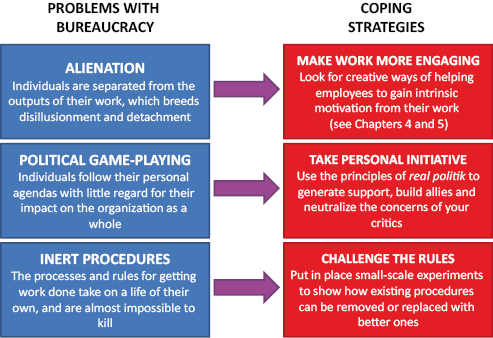

So if the previous two chapters were about understanding and remedying our insensitivity to our employees, and our own personal biases, this chapter is about recognizing the limitations and pathologies of the organization that surrounds us – and finding ways of coping. As suggested in Figure 6.1, bureaucracy has three primary pathologies.

Figure 6.1 The Problems with Bureaucracy and How to Cope

First, it results in alienation – a feeling of disillusionment or detachment on the part of the individual worker, when he is separated from the product of his labour. This was Karl Marx's insight, and of course it led him down a path towards class warfare and communism that proved to be a dead end1. However, his original insight was spot on, and the need to find ways of helping workers to become more involved in their work and in the fruits of their efforts is as great as it has ever been.

Second, bureaucracy gives rise to political game-playing. The definitive insight here came from the French sociologist, Michel Crozier, who observed that so much of what happens in bureaucracies is decided in advance, that the only way people are able to gain some control over their working lives is to exploit “zones of uncertainty” where the outcomes are not already known2. Thus, interactions in large organizations become a series of games and power struggles, in which people pursue their personal agendas, with little or no regard for their effect on the organization as a whole.

I doubt I need to convince you that big organizations are hotbeds of political maneuvring and game-playing. Some managers are simply self-interested, only contributing to a cause when it suits their immediate needs to do so. Others are schemers, taking delight in sabotaging the plans of others as a way of furthering their own agenda. Of course, not all managers act in these ways, but if even a minority do, it means everyone else has to adapt their behavior accordingly.

Third, bureaucracy allows inert procedures to emerge. As we saw with my Webinar story above, these processes take on a life of their own and are almost impossible to kill. They support the primary value-adding activities of the firm, but they are often two or three steps removed from the marketplace, so feedback from customers gets filtered out and lost. They have their own managers, who have strong vested interests in keeping their jobs. These processes are dependent on each other, creating a tightly woven matrix of activities that cannot easily be pulled apart. The budgeting process is perhaps the definitive example, a process that according to one book is “time-consuming, adds little value, and prevents managers responding quickly to changes in the business environment.3”

Most of the previous two chapters were about finding antidotes to alienation, for example, by getting inside the mind of our employees and looking for creative ways of making their work more fulfilling. So I won't give this issue any further consideration in this chapter. Instead, I will focus on the second and third pathologies. We can overcome political game-playing through personal initiative – by rising above the petty games of our colleagues and by coming up with creative ways of making a difference. We can also overcome our inert procedures by seeking out creative ways of challenging them or renewing them.

The truth is, though, that cases of successful, top-down transformation are rare, and even when they occur they typically involve a lot of small-scale, under-the-radar experiments that collectively make the overall transformation possible.

So my advice to mid-level managers is always the same. You cannot change the entire system. You also cannot afford to ignore the rules altogether, because you will be out of a job before you know it. So the way forward is management experimentation – a conscious and structured process for putting in place new ways of working. I will get into a detailed discussion of the hallmarks of a good experiment later in the chapter, but at a minimum it requires a clear hypothesis (for example, if we give employees 4 hours a week “dabble-time” innovation will increase); it is limited in its scope and duration to keep the level of risk under control; and it takes place in a real-world setting, to ensure the findings are meaningful. The If insurance example in the previous chapter was a classic experiment, as it represented an explicit test of the hypothesis that greater coaching of employees by a front-line supervisor would increase their sales competence.

Let's take a look at the different ways experimentation can help you to overcome the political game-playing and inert procedures in your organization.

Take Personal Initiative – To Overcome Political Game-Playing

When something isn't working very well, you can take the path of least resistance and just put up with it or you can follow the path less travelled and try to improve it. This was the crossroads that Jordan Cohen, Director of Organizational Effectiveness at Pfizer, was standing at in 2005. He realized people were wasting a lot of time on low-value, run-of-the-mill work, like building spreadsheets, booking travel, and doing background research. Given the enormous cost pressure the company was under at the time, this seemed like an obvious area where greater efficiency was possible. “I noticed one of my team, Paul, an MIT graduate, spending time after hours doing tasks that were not just below his pay-grade but not core to his role either,” he recalls. “I knew there had to be a way to unburden him from this low-value work.4”

Pfizer wasn't an organization that encouraged bold moves. It was a leader in a highly profitable and highly regulated industry, and it exercised due caution at every turn.

Seeking to turn his observations about Paul into something tangible, he drew inspiration from Tom Friedman's The World is Flat, which opened up his eyes to the possibility of taking advantage of the global marketplace for services. He came to the realization that outsourcing could be done at a microlevel, around individual tasks. The pitch to his colleagues was: “I think I can help by delivering that to your inbox within 24 hours so you don't have to do it … it may cost a little bit of money but it will be just as good as if you did it” (note that he did not say, “I can outsource this for you” – he quickly learned that the term outsourcing had negative connotations). This resonated strongly across the company, and it gave him the impetus to turn his idea into an experiment.

Jordan first collected some data, and he was able to show that colleagues were spending 20–40% of their time on noncore work. He immersed himself in the practice of outsourcing, developing detailed knowledge of the types of services readily available, how to select and manage vendors, and how to ensure a high-quality service. By working evenings and weekends, Jordan was able to design a prototype program within just a few months – a service that colleagues could access at the click of a button, to secure one-stop support for such things as business research, data analysis, and creating documents.

Having a working prototype allowed Jordan's colleagues to start using the service and for him to learn how to make it work properly. As he recalls, “When I first started this, I didn't know what I was doing. By the time I finished, I was an expert. We weren't just looking at the output on a monthly or weekly basis, we were looking at it every night, and we were putting fixes in place immediately.” Plenty of mistakes were made – “I personally bought a lot of drinks for people, I apologized, that's what you do” – but within one year the service was operating in pilot form.

Moving from the pilot to a fully fledged operation took another year. Getting the name right was a challenge. Virtual assistance was Cohen's first proposal, but it sent the wrong message to the firm's secretaries who worried they were being replaced. Office of the Future became the working title, which gave way eventually to PfizerWorks. Cohen also had to get buy-in at every level, even meeting with the CEO to get the final endorsement to proceed.

Jordan didn't face any outright hostility in pursuing this initiative. In fact, no-one ever told him it was a bad idea, but there was a real risk of death by a thousand cuts. Some people were sceptical. Others were disinterested. Most had better things to do than help him. Faced with this mass indifference, he could easily have given up, but instead he chose to rise above it, and get PfizerWorks off the ground. So what were the tactics he adopted? What advice does he have for others who would like to transcend the narrow personal agendas of their colleagues?

Cohen has some very clear advice here. As well as getting his boss on board early, he also built a web of partners inside and outside Pfizer. Internally, he worked with a core group of “friendlies” – people who he had an existing relationship with, who would give him good feedback. Externally, he found some suppliers who would partner with him at minimal cost. However, once the project started to gather some steam, he realized there were some important capabilities he didn't have. For example, as a headquarters-based manager, his knowledge of the field force was limited. So rather than spending a lot of time building field credibility, he opted to bring in a team member who really understood the field.

In sum, Jordan Cohen made PfizerWorks a success through the corporate equivalent of real politik – a strategy built around understanding and responding to the personal interests of those around him. The tactics he pursued were all about avoiding or defusing criticism, and gaining support among those who could help him to make PfizerWorks a success. In an ideal world, where organizations worked without flaws, he could have focused purely on getting the technical aspects of the project right, but by recognizing the inherent limitations of a huge company like Pfizer, and responding appropriately, he was able to make the project a success.

Challenge The Rules – To Overcome Inert Procedures

Jordan Cohen's tale is one of patience and tenacity, of accepting the constraints of the system and working within and across them to get things done. All credit to him – many people would have simply given up somewhere along the way.

However, there is another way forward when faced with a wall of resistance to your well-intentioned initiatives: namely, to set about tearing the wall down, brick by brick if necessary. Of course, I am not going to recommend you pursue a sophisticated form of career suicide. Deliberately breaking the rules can work, but it can be very dangerous as well5. I recommend a more prudent approach. The starting point is to be very clear on your own degrees of freedom – your level of authority and the tolerance for change of those to whom you are accountable.

So here is an important question: Are you the boss? And when I say boss, I mean is there an area of business that you are fully accountable for? This could be an entire corporation or more likely a single business unit, function, or department. If you are, then you have the opportunity to “just do it.” Of course, there is still an issue of how you manage up, to keep those above you informed and on-board, but that shouldn't stop you from doing what needs to be done. Here are two examples of top-down approaches.

This view led Bayliss to formulate a couple of initial experiments, one allowing branch managers to set their own opening hours, the other giving them control over their marketing budgets. “Within six months, nearly 95% of our stores had altered their hours in some way, to better serve their local customers. For example, in one Auckland suburb, we became the first bank to open on a Sunday morning, allowing us to service the thousands of customers who flooded the local farmers' market.” While these experiments were, naturally enough, popular with branch managers, they led to some surprising new insights. Many branch managers, for example, didn't have the skills or courage to be effective in this new empowered workplace. Bayliss also had to work hard to overcome objections from some corporate functions. HR was concerned that changing hours would raise objections from the employee union, so store managers had to get agreement from all employees. Marketing also thought that the hand-lettered signs being used to advertise store hours looked tacky, so they developed a software template that allowed store managers to print out a simple sign with store hours. The results of these changes had a rapid impact, with 10% growth in sales after the first year and employee engagement ratings at around 85%.

How did he get support for these changes? The challenge was one of managing “sideways:” persuading the corporate HR team, the technology people, the risk function, and the corporate branding team that these changes had very little downside and a lot of upside. So at the end of the day it was about educating them: “I'm a great believer in storytelling and what we did is we were very effective at promoting best practice and telling the stories of the successes.”

It's not easy to put your finger on exactly what Ross Smith's experiment was, but that's partly the point. He knew the traditional hierarchical model of management wasn't going to work for him, or his team. But trust and creativity aren't things you can mandate, so instead he threw the responsibility for defining them back to the team – he gave them the tools and the space to experiment and he waited to see what would emerge. Not surprisingly, the team responded enthusiastically. Mark McDonald, Microsoft's first employee, a friend of Bill Gates in high school and a key member of the team, observed, “42Projects tries to recapture the feeling and passion you have at a small startup or at the beginning of an industry by breaking down the stratification of a large organization.” Mark Hanson, another team member, concurs: “We're giving people the latitude to go off and do their own thing. We trust them to do their regular jobs and to experiment, innovate, and have fun. We're developing a level of trust where there's no required accountability that you need to log your time or provide an example of what you did during that day when you worked from home.”

Let's be clear, Chris Bayliss and Ross Smith didn't do anything really radical. It is the boss' job, after all, to look for ways of improving the way work gets done in their organization and to create a culture that fits with their personal style of operating. But for every one of these stories, I can point to 10 stories of bosses who chose not to challenge the management systems they inherited. These more conventional bosses chose to prioritize other things, and perhaps they lacked the creativity or tolerance of uncertainty that Bayliss and Smith exhibited.

So of course I strongly encourage you, as a boss, to challenge how work gets done in your part of the organization. This doesn't mean taking inordinate levels of risk. We sometimes hear about case studies of truly radical approaches to management – Ricardo Semler at Semco, Lars Kolind at Oticon – but there are enough examples of better ways of working out there, from books such as this one, for your approach to be both progressive and proven at the same time.

But what if you are not the boss? If you are a mid-level person within a sizeable organization and you are getting frustrated by the sclerotic management processes getting in your way, do you have any possibility of making changes? Well the answer is yes, but you need to proceed cautiously and to take very seriously the notion of experimentation.

Bureaucracy-busting at Roche. Consider this example from the Swiss pharmaceutical giant, Roche. The company has a mission that puts innovation at the heart of what it does, but among many employees the perception is that bureaucracy detracts from this mission. So in 2009 a cross-functional team, working under the banner of a leadership development program, set about trying to shake things up. Realizing that they couldn't tackle bureaucracy as a whole, they decided to focus on one particular process, travel and expense claims. That might not seem the sexiest call, but it had several advantages. After all, the team wanted to test a general hypothesis – that cutting bureaucracy was not only feasible but desirable – and travel expenses ticked all the criteria. It certainly epitomized in fairly extreme form the misalignment of values that drains professional effort and commitment. “I'm responsible for $60m sales but need approval to buy a $3 cup of coffee,” as one participant manager summed up the general mood. As well, the team was startled to find that Roche Pharma's annual travel budget added up to more than $300m – so the stakes were potentially higher than many people had expected8.

To make progress, the team planned and got permission for an experiment. They came up with an ingenious design comprising two pairs of matched groups, one pair taken from the Basel headquarters, the other from a sales affiliate in Germany. In each pair there were 50 people per group, so a sample of 200 people in all. One group was a control whose travel authorization process continued to operate as before – those “participants” had no change in their current process. The second group in each location, however, was told that as part of the pilot project their travel was to become self-authorized. Subject, of course, to normal company policy (who was entitled to travel business class, etc.), Roche employees made the decision to travel and book their flights and hotels, with no further approvals (no approval to travel and no signature for expenses after the trip). The proviso was that expenses information would be transparent, posted on the Intranet for other employees to see.

The experiment was designed to test three things. Would people be more motivated by removal of the bureaucratic process of pre-authorization? Was the new process simpler than before? And what would be the consequences for costs? The first two were measured by before-and-after surveys. To avoid as far as possible the operation of a “Hawthorne effect” (people working harder and better because they know they are being watched) the team had taken care to downplay the experimental nature of the project by keeping it very low key.

The results were astonishing. Instead of the neutral to modest improvement expected, 45% of participants said motivation had increased as a result of the changes, with another 46% reporting no change; 83% of the sample felt that the approach was better attuned with Roche values and wanted it adopted as normal procedure. Only a very small minority – 6% – were uncomfortable with having their expenses available for others to see. Similarly overwhelming majorities (74% and 87%) reported that the new process was more efficient and took less time than the old one – “Inefficient approval process for travel; sometimes I have the feeling I work at a government authority,” was one heartfelt comment. As to cost, the team had fully expected travel costs to go up with self-authorization. In actual fact, the expenses of the two experimental groups went down, one quite substantially, while totals of the two control groups were unchanged. This was something of a revelation. “I hope my expenses will motivate others to spend as little as I do!”

The experiment was a real eye-opener for the members of the team. The idea that “insight” into travel expenditure could be more effective than formal “oversight” began to get real attention. In late 2009 they presented their findings to the Executive Committee, and they were asked to put together a roll-out plan to implement it to key sites globally. Their experiment also inspired others in Roche to take a closer look at some of their other management processes, to see where further improvements could be made.

So what are the lessons from the Roche experiment? How might you set about challenging the way your organization works?

Another example of the value of moving quickly comes from a team of executives I worked with in Scandinavian insurer, If9. They were looking to dramatically simplify and improve the quality of their online offering with private insurance customers. Rather than go through the standard development methodology, they got permission to do a six-week experiment. While this created enormous pressure, it was also a key factor in their success: “It focused us and meant we had to cut away all those project management methodologies that add to the time of making change happen,” says Katarina Mohlin, a member of the team. “We had to identify shortcuts, like using existing usability studies, rather than setting up a brand new focus group.” By positioning it as an experiment, not a pilot, they overcame concerns about whether it would be a success or not. “A pilot requires a detailed business case with cost rationalization. An experiment allows the business case to be developed after the initial feasibility has been done,” notes Jorgen Hiden, another team member.

Notice that implementing an experiment involves a very different mindset to running a pilot, which assumes a particular course of action but with a bail-out clause if things don't go to plan. The guiding philosophy here is to maximize learning, not minimize risk.

Making Your Experiments Stick

I spend a lot of my time working with managers on small-scale experiments of this sort. While they usually yield interesting and valuable findings, the reality is that most of them don't end up getting rolled out company-wide. For example, the expense-claim experiment at Roche was very well received internally, but at the time of writing it had not been implemented across the organization.

So I am often asked, doesn't this frustrate you? And doesn't it call into question the entire logic of experimentation? My answer has three parts.

First, management experiments that challenge the rules serve the important function of forestalling further bureaucratic creep. In my mind, bureaucracy is akin to a gravitational force, and the larger the organization, the stronger the force becomes. This means that large companies have to run as fast as they can just to stand still. They need managers throughout the system to be on their guard; questioning the way things are working, trying out alternatives, and pushing back on new rules and regulations.

Second, the discipline of designing and running a management experiment provides enormous personal learning. These experiments are often run under the auspices of a corporate leadership development program, and one of the key themes in such programs is typically closing the knowing–doing gap. It is useful to talk about this gap, to make people aware of it, but it is even more useful to do something about bridging it. Experimentation provides the bridge: it compels the managers involved to translate their abstract ideas into operational hypotheses and then into a series of discrete actions. These actions can then be scrutinized and evaluated against the original hypothesis. In my experience, this is a really effective way of enhancing the attentiveness and self-awareness of managers.

Third, management experiments are sometimes really successful. For example, the If insurance experiment that was discussed at the beginning of Chapter 5 led directly to a rethinking of the company's entire approach to coaching and mentoring. The experiments conducted by Chris Bayliss and Ross Smith above have both had an enduring impact on their organizations. Many other companies have also had good experiences with their management experiments. The best single source for reading up on these is the Management Innovation Exchange (MIX), a free online resource at www.managementexchange.org.

Of course, it should be no surprise that many management experiments don't seem to go anywhere. The essence of innovation in all walks of life is that most ideas fail. A pharmaceutical company needs to screen thousands of potential targets to identify dozens of candidate drugs, in order to yield a single viable new drug. Perhaps the ratios are a bit different in the field of management, but the principle that “failure” is a more likely outcome than “success” is one that we need to continuously remind ourselves of.

Making The Best of an Imperfect World

It is very easy to become frustrated by the apparent irrationality of the organizations in which we work. Some people yearn for more rules and procedures as a way of creating order and reducing the amount of time resolving disagreements. However, the more rules and procedures you create, the more depersonalized work becomes and the more introspective and self-defensive people become. To paraphrase Winston Churchill, bureaucracy is the worst organizing model in the world, except for all the others.

So what is the way forward? We can certainly try to identify alternative ways of coordinating our business activities, whether by using more market-like techniques or community-based principles of self-organizing. My previous book, Reinventing Management, had an entire chapter on this subject, but for the most part, we will all end up working for large organizations that operate in an imperfect way. Our job, as effective managers, is to develop the tactics and skills to function effectively in such a system.

Notes

1 Marx, K., Capital: Critique of Political Economy, 1867.

2 Crozier, M., The Bureaucratic Phenomenon, 1964.

3 Hope, J. and Fraser, R., Beyond Budgeting, Harvard Business School Press, Boston, 2003.

4 Personal interviews with Jordan Cohen. There is also a case study published by IESE Business School: Jordan Cohen at PfizerWorks: Building the Office of the Future, IESE DPI-187-E, 2009.

5 See: Klein, J., Hacking Work, 2009, for some nice examples of risky bottom-up initiatives.

6 This story about Chris Bayliss at Bank of New Zealand is taken from an article written by him in the Management Innovation Exchange. http://www.managementexchange.com/story/not-just-ordinary-day-beach-unshackling-employees-bank-new-zealand.

7 Personal interviews with Ross Smith. Part of this story was also referenced in my previous book, Reinventing Management.

8 This story was taken from “Roche: From Oversight to Insight,” Labnotes Issue 16, www.managementlab.org.

9 This story was taken from “Giving Customers What They Want,” Labnotes Issue 20, www.managementlab.org.