5

Doing What We Know We Should: Managing As an Unnatural Act

If you want to make improvements to the practice of management, start in your own backyard. This was the view of a team of executives at If, the leading Scandinavian insurance company. As part of a strategic review, they had become aware of the untapped talent of many front-line employees, and they developed the simple hypothesis that this potential might be opened up with a more supportive and coaching-oriented style of management. “We thought that by acting in a slightly different way, and emphasizing intrinsic rather than extrinsic motivation, our managers might make a real difference to the competence and performance of our employees,” recalls Hakan Johansson, one of the executives1.

So here is what they did. They identified a team in Johansson's division – an already high-performing team selling insurance for cars by phone – and they persuaded the team leader, Lotta Laitinen, to make some changes to her management style. Lotta was excused from two hours a day of meetings and routine admin (which were handled by an obliging colleague), time which instead she would spend directly with her team, both jointly and individually.

The process was kicked off with a workshop, introduced by Johansson, in which Lotta's team was asked to discuss the value of cross-selling, and how it might be improved. “This was the starting point for it, to give more influence to the team,” noted Niclas Ward, one of Johansson's colleagues. Following this workshop, Lotta, with her extra two hours a day, began working much more closely with the team, working with the high performers to understand the tricks of their trade, listening to sales calls, and coaching members of the team on a one-to-one basis. Team members were also encouraged to listen to and coach each other, with Lotta also joining in and giving feedback.

After three weeks of the new way of working, the results were measured in three ways – by actual performance, through a questionnaire completed by the whole group, and by selective interviews. The headline figure was a 5% increase in sales, compared to the three previous weeks. The overall figure concealed some unanticipated differences: notably, there were major improvements among the hitherto below-average performers. The questionnaire responses were uniformly positive, team members strongly agreeing that the approach was indeed different, that they had more freedom to work in the way that suited them, that they got more time with the leader, and that they felt more motivated. The highest score was recorded by the proposition “I would like to work the way we worked in the last three weeks in the future.” Lotta's reaction was also positive, initial hesitancy giving way to strong enthusiasm as the trial went on and she continued to find fresh ways to work. She was adamant that she missed nothing by not going to the meetings. “The first week was really stressful, because I had to make plans for the three weeks,” she summed up. “But by the middle of the test period, I was more relaxed, and I was satisfied when I went home every day because I felt I had had a great day.”

So were the If executives happy with this outcome? Absolutely. A 5% boost in sales over three weeks is impressive and bringing up the performance of the weaker members of the team was a real plus. The cost of the intervention was minimal – Lotta was confident she could continue to carve out more time for coaching, even without the help of an obliging colleague, by simply becoming more efficient in her administrative tasks. At the time of writing, Johansson and his colleagues were looking to scale this initiative up: “We are now developing specific plans for how to help our front-line managers across the organization become more effective coaches, and how to free up some of their time so they do more of the real value-added parts of their job. There is a big payoff to the company if we can get this right.”

Here is the real point of this story. Just like Google's advice on how to become a better manager (mentioned in the introduction), the notion that coaching your employees might help their performance is obvious. All it took was a simple and deliberate intervention from Hakan Johansson and his colleagues for a worthwhile change in behavior to occur. Why had this change not happened earlier? I don't believe Lotta was at fault – in fact she was chosen for the task because she was competent, personable, and open to new ways of thinking. However, like so many other managers in companies around the world, she was so busy with tedious administrative jobs that she wasn't making the time to do the potentially more valuable parts of her job.

Doing What We Know We Should

This chapter is about how you can do your job as a manager more effectively – how you can become a better boss. In the previous chapter, the focus was on knowing your employees better and seeing the world through their eyes. In this chapter, the focus is on knowing yourself better. As managers, we like to think we are doing a good job but, if we are being truthful with ourselves, we know there are things we could do better, especially in terms of how we get the most out of our employees. Just flip back to the list at the end of Chapter 2: what employees want is challenging work, space, support, and recognition. Do you consistently provide these things to all your employees? My guess is sometimes you do, but at other times you lapse back into less desirable behaviors such as micromanaging, selfishness, or inattentiveness.

Why don't we do what we know we should? Again, Chapter 2 provided the simplistic answers: we are too busy, we have conflicting priorities, and our employees have such different needs that it is hard to keep them all happy. But there is much more going on here as well. This so-called “knowing–doing” gap is a pervasive problem, even with managers who have plenty of time and few direct reports.

I think there are two linked explanations for the knowing–doing gap in managers. One is that many managers don't truly, deeply believe in the importance of giving their employees lots of space, or coaching them, or providing proper feedback. Seasoned managers develop a point of view based on their personal experience, and this typically trumps any sort of research-based findings as a guide for action. So even if a manager accepts – intellectually – the findings about what might make him or her more effective, he or she will often quite happily act in a contrary way, just based on personal experience.

The other explanation is that we don't turn knowledge into action. Using the terminology popularized by Chip and Dan Heath in their best-seller Switch, the rational part of our mind, the “Rider,” has figured out the path to take, but the emotional part, the “Elephant,” isn't moving. Just like losing weight or exercising more, there are aspects of good management that we know we should do, but other things just keep on getting in the way. We lack the self-control to do what we know we should.

In this chapter, we discuss these arguments in detail and we lay out a way forward. To become a better manager, you need to develop self-awareness, so that you are more conscious of the less-than-rational ways you often behave. Armed with these insights, you can then develop a set of techniques and tricks to help you change your behavior. This chapter will highlight what some of these tricks are. Changing your own behavior is not easy, but it is possible, and the rewards – for you and for your team – are substantial.

Why Do We Behave the Way We Do?

There is mounting evidence that we are all behaviorally flawed. We have biases and shortcomings in the way we process information and how we act on it. These biases detract from our ability to take the rational or smart course of action in a particular situation.

Psychologists have been studying these behavioral flaws for a very long time, but over the last decade or so the world of mainstream economics has belatedly come to realize that these apparently small deviations from their rational theories of human nature actually have profound consequences for decision-making, human interaction, and life in general. The field of behavioral economics is now growing rapidly and its findings are influencing corporate boardrooms and government policymakers alike.

Behavioral economics attempts to make sense of the weird and wonderful ways the human brain works. Daniel Kahneman, Nobel Laureate and founding father of this field of research, says that problems stem from the fact that we have two parallel systems in our minds:

- System 1 operates automatically, with little or no effort. We can detect hostility in a voice, drive a car on an empty road, or understand simple sentences, without any sense of voluntary control.

- System 2 requires the conscious allocation of mental effort. If we want to check the validity of a logical argument, monitor the appropriateness of our behavior in a social situation, or tell someone our phone number, we have to pay careful attention to the task in hand2.

These two parallel systems have been characterized in many different ways: the doer and the planner; the emotional and the rational; the id and the superego; and the elephant and the rider. Very often, our behavioral flaws occur because System 1 (the elephant) has already reacted to a situation before System 2 (the rider) has had a chance to intervene. This is why we procrastinate, why we make snap decisions that are wrong, and why we occasionally get into fights. Sometimes, though, the problem is the other way round and System 2 takes over, leading us to overanalyse a problem or become overwhelmed by the choices we face.

Why do our brains work this way? There isn't complete agreement, but one influential line of thinking called evolutionary psychology says that the minds and bodies of humans are, in large part, adapted to the demands of their ancestral environment – the “social clan life of mobile hunter-gatherers” that was still the dominant way of life until around 10 000 years ago3. In essence, this theory says the human mind is evolving over time, but it is struggling to keep up with the speed of changes in human civilization, so we end up with mismatches between our “natural” response to a situation (i.e., how our ancestors would have responded) and the “appropriate” response (i.e., what works best in a modern context). This is why we prefer to work in small teams, not in large impersonal organizations; why we make risky bets when faced with the prospect of loss; and why we react violently when we feel threatened, even if we put ourselves in danger in the process.

While I found these arguments pretty persuasive, I realize that many people find it a bit of a stretch to link the actions of hunter-gatherers on the savannah to modern day human behavior. So be it. For our purposes here, it is much less important to worry about the origins of our behavioral flaws than to recognize how and where they manifest themselves. We need to be conscious of our own biases and shortfalls, so that we can take the appropriate remedial actions.

So here is the key idea in this chapter. For the majority of us, management is an unnatural act4. We know what good management looks like, but it takes a lot of conscious effort to follow through on it. Using Kahneman's terminology, our System 1 response as a manager is often very different to what our System 2 logic would tell us we should do, so we have to work extra hard to do what we know we should. Using the logic of evolutionary psychology, the reason good management is so difficult is that our natural predisposition is towards what worked in our ancestral environment – which was about hunting and foraging in small tribes, not coordinating large, diversified organizations.

Fortunately, our conscious mind is able to get to grips with this dilemma. In the words of management writer David Hurst, our true nature is “an ancient selfishness overlaid with a profound ability to cooperate and varnished with a thin layer of reason.5” It is this thin layer of reason, part of Kahneman's System 2, that I am appealing to here, so that you as an individual can find ways of making the unnatural act of managing a little more natural.

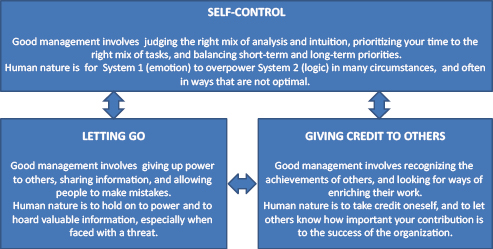

To provide some structure to the rest of this chapter, I think it is useful to break good management down into two linked sets of principles: letting go, which means giving up power to others, sharing information, and letting people make mistakes; and giving credit to others, which means recognizing their achievements and looking for ways to enrich their work. Sitting above these two sets of principles is a third principle we can call self-control, which means making the right trade-offs and choices among competing alternatives. Figure 5.1 illustrates how these three principles fit together.

Figure 5.1 The Three Basic Principles of Good Management

Letting Go: Why is it Difficult?

One of the hallmarks of a good manager is the capacity to let go – to give power and freedom to others, to share information freely and willingly, and to allow people to make mistakes. We know from Chapter 2 this is what our employees want us to do and we know from Chapter 1 that a people-centric culture based on empowerment and shared information drives long-term success.

But letting go is difficult to do. It is human nature to hold on to power and to hoard valuable information. This is especially true when things are not going well: if your organization is under threat, you are likely to be become more controlling, by asking for more frequent reports and checking details that you would normally have delegated.

Why the gap? Research shows there are three linked things going on here:

Put these three drivers together and you can quickly see how they lead to suboptimal management behavior. The principle of loss aversion encourages managers to work extra hard in a tough market to ensure they deliver on their promises, which almost always involves more oversight of subordinates. The illusion of control reinforces managers' belief that their involvement is critical to the outcome of a decision. The knowledge-is-power syndrome also encourages managers to keep information to themselves, typically under the delusional belief that it is confidential.

I have personal experience of how this plays out. A few years ago, I was involved in launching a new product that various stakeholders didn't like. My role was to work up the business plan, think through the specific details of the product, and to assuage the concerns of the unhappy stakeholders. During one critical period before launch, I was working 10 hours a day on the project, often negotiating with several stakeholders simultaneously. What I needed to do my job was the freedom to make my own decisions and to communicate swiftly. However, my boss was also feeling the heat from his stakeholders, so he responded by reining me in, second-guessing some of my decisions, and micromanaging my communications. This of course made things worse, as we wasted a lot of time arguing about the best course of action rather than just getting things done.

Here is another example. Many companies over the last decade have introduced the notion of a “performance contract” between a business unit and corporate headquarters, as a way of specifying what has to be delivered, but leaving lots of discretion to the business unit managers in terms of how it will be done. In theory it is a good way of pushing decision-making closer to the action and empowering business unit managers. In practice, though, the performance contract has often become an insidious device for achieving the exact opposite outcome. I was talking to a senior executive in one of the big five UK banks and he explained how their performance contract had gradually grown in length, from a focus on 4–5 measures to a list of more than 15 different measures. “I have so many things I am now accountable for,” he explained, “that I have lost most of my managerial discretion. There are just too many things I am being measured against. The performance contract has turned into a big stick – something to beat me over the head with.”

Letting Go: Some Advice On Doing it Better

So what can you do to be more effective and more consistent in letting go? The starting point, as always, is to get it clear in your own head why giving your employees freedom is the right approach. Everyone has their own way of doing this and you have to try a number of different angles before finding the one that resonates best. A friend of mine, Andrew Dyckhoff, is an executive coach, and he expresses it in the following way: “I ask the person I am coaching, do you hold yourself to higher standards than those around hold you to? Yes, they invariably reply. So I ask the supplementary question: so why would your employees, the people who work for you, not do the same?” By exposing this implicit double standard, Andrew helps the executive to think more carefully about the amount of trust he has in those around him.

A related approach is to be more honest about what is holding you back from delegating and sharing more with your employees. In one recent piece of research I was involved in, we asked managers to assess (a) how important and (b) how easy to delegate their various day-to-day activities were. Perhaps unsurprisingly, they said the least important activities were also the most easy to delegate. Which begged the question, why on earth were they not delegating these things? On further inspection, it became clear that many of these activities were things the managers got some sort of tacit utility out of – departmental meetings where they had an opportunity to banter and gossip, email exchanges where they could impress others with their knowledge, developing powerpoint slides because they just didn't trust others to get them right. Of course, there is nothing wrong with these reasons, but the point is we need to be clear what our own sources of motivation are in order to help us decide what to delegate and what to keep control of.

Here are four techniques I have observed and experimented with over the years, all designed to help us become better at letting go:

“I went into this one branch and they'd got this children's party banner that said ‘surprise, surprise’, blu-tacked right across the line of tellers, completely contravening our usual policies. And I thought, what do I do, this is the test isn't it? I stood in the banking hall talking to the branch manager, I kept looking at this banner thinking okay how do I bring this up, I've got to coach and talk to him about it. And you know what, while we were stood there every bloody customer comes in and says to the tellers, what's the surprise? And you know what, the tellers had this brilliant script and I just stood there with my eyes open, thinking, well the customers don't seem to mind, the staff are on fire, and they're converting it into sales. So who's right and who's wrong?”

Letting go of power isn't rocket science – the basic tricks and techniques are obvious to everyone; it's just a matter of finding the ones that work for you. There is a caveat, of course, which is that letting go doesn't mean abrogating your responsibilities entirely. Good management involves keeping track of what your employees are up to, but without taking their accountability away. If I can boil this advice down to a single sentence, it reads as follows, with due apologies to Reinhold Neibhur, author of the serenity prayer: “Grant me the courage to give power away, and the wisdom to know when to take it back.”

Giving Credit to Others: Why Is It So Difficult?

The second basic principle of good management is to give credit to others – to recognize their achievements and to look for ways of enriching their work. However, this isn't an easy principle to live by, as it is human nature to take credit for your own achievements and indeed to believe that your own skills and capabilities are superior to those of the people around you.

Giving credit to others isn't quite the same as letting go, although obviously they are linked. Giving credit to others involves downplaying your ego; letting go involves downplaying your involvement. More often than not they are flip-sides of the same coin, but the underlying factors that shape them are different. Here is what we know from the psychology and behavioral economics research:

If you take these four points together, you end up with a fairly predictable set of consequences. The manager is convinced of his or her own superior skills and judgment and takes credit for the achievements of the team. The team then reinforce his or her self-image, because the manager is in a position of power over them. Taken in aggregate, this pattern of behavior has been observed in many different contexts. For example, studies have shown how overconfident and egotistical CEOs make more risky and expensive acquisitions, and fail to heed the warning signs when things go wrong12. My colleague, Nigel Nicholson, did a study of UK corporate leaders a few years back and found them to be “single minded, thick skinned, dominating individuals.13”

Giving Credit to Others: Some Advice On Doing It Better

So how can you become more effective at giving credit to others and downplaying your own achievements? A useful analogy is to the world of share trading. Because we are loss-averse, our instinct is to harvest our winnings and to retain poorly performing investments in the hope that they will rebound. However, a much better strategy is to do the exact opposite – to cut your losses and ride your winners. Even though professional traders know this, they still need the message to be reinforced on a continuous basis, because it goes so sharply against their instincts.

I propose a similar mantra for you as a manager: own your failures, share your successes. Your natural predisposition is to do the opposite, so as a rule of thumb, as a guide to behavior when you are uncertain how to proceed, sharing your successes is almost always the right way forward. For example, Vineet Nayar, former CEO of HCL Technologies, has spoken about “destroying the office of the CEO” as a way of spreading accountability across the company and reducing the amount of credit he receives for the company's successes.

As with letting go, there are some specific techniques that you can employ to make this a bit more practical for yourself, whatever position you sit in within your organization.

Now I realize this approach is risky. If your enlightened approach to management is not shared by your boss, it is possible that the goal of “working yourself out of a job” may actually end up with you having no job. In my experience, however, this discipline of pushing as much work down as possible actually had the effect of changing the nature of the work I did as a manager – it forced me to spend more time on mentoring and supporting activities and it resulted in better performance all round.

In a related way, I have sometimes observed that interim managers are often more effective than permanent ones. This is in large part because they see their job as enabling others, rather than making themselves indispensable. They typically see their job as “making the trains run on time” rather than imposing a grand new strategy on the organization. Often this approach inspires those around them to take more responsibility and work more effectively.

A related approach is to be more creative at carving out semi-autonomous pieces of work within a larger project. You may be responsible for the entire project, but if your employee can own one piece of it, and attach his or her name to it, then your needs and that of the employee will both be met. In a very different setting, this was the approach adopted by Antoni Gaudi when he put together the blueprint for the Sagrada Familia church in Barcelona. Realizing that it would not be finished until well after his death, Gaudi encouraged other architects to create their own designs within his own master plan, to ensure that they felt some ownership for the work.

So how can you become better at taking ownership of your failures? One prerequisite is unfiltered feedback, that is, advice and evidence that tells you when things have not gone well. Some organizations push the principle of straight-talking, whether boss to subordinate, subordinate to boss, or peer to peer. At Intel this principle is called Constructive Confrontation; at McKinsey it is called the Obligation to Dissent; at Bridgewater Associates it is called Radical Transparency. Ray Dalio, the Bridgewater CEO, observes, “I believe that the biggest problem that humanity faces is an ego sensitivity to finding out whether one is right or wrong and identifying what one's strengths and weaknesses are.14” So he has deliberately pushed an organizational model that encourages brutally honest feedback.

If you don't work for a company that takes feedback seriously, you have to nurture your own critics: sometimes this is an executive coach; sometimes it is personal friends with no immediate stake in your success; sometimes it is an anonymized 360 review that gives your subordinates a licence to say what they really think. In economist Tim Harford's terms, these people represent a validation squad who can help you overcome your enormous capacity for self-delusion15.

Self-Control: Why Is It So Difficult?

The third principle of good management is self-control – the ability to regulate your own emotions and instincts. As we have seen, good management is often about overcoming your natural instincts, but not always. There are times when an emotional response is more powerful than a rational one and there are some situations where a “gut” decision is better than the one reached through careful analysis. So if the two previous principles were essentially about downplaying your instincts, this one is about learning how to strike a balance – about knowing yourself so well that you can switch back and forth between the two different modes of operating: emotional versus rational behavior or intuitive versus analytical decision-making.

Let's be clear: self-control as I am describing it here is really hard to achieve. In many situations, we don't have time to metaphorically stand back and decide how we will respond. Moreover, if we behave in a way that doesn't look natural to those around us, we come across as devious and lacking in authenticity. So the message is not to abandon your natural style of working. Rather, it is to be sufficiently knowledgeable about the benefits and limitations of your natural style that you can catch yourself before you make a blunder. Here is a simple personal example: my natural style in a meeting is to be logical and calm, and to be agreeable with those around me. These are often very helpful traits, but occasionally, if a decision is contentious, I run the risk of looking ineffectual. So I have learnt to push back every now and then, and respond with more emotion.

What does research tell us about self-control? A great deal, it turns out. Here are some highlights:

The practical lesson for all of us is clear: if we want to make difficult decisions – ones that go against priming and experience – we should do it when we are well rested and well fed. More broadly, it is useful to know what our general state of mind is before performing our various managerial duties. Daniel Kahneman has shown that when in a state of “cognitive ease” we are more creative and intuitive, and less careful, whereas in a state of “cognitive stress” we tend to be more analytical and suspicious.

We should be cautious, in other words, when relying on our intuitive expertise. Unfortunately, most executives don't want to heed this advice: research has shown that being in a position of power makes people more, not less, likely to simply follow their gut instinct21.

Put the findings from these studies together and again the net effect is predictable. Even as respected and thoughtful executives, we frequently become cognitively lazy: we go with the flow, in terms of what our System 1 thought processes steer us towards; we allow our behavior to be primed by the situation in which we find ourselves; and we make snap decisions, convinced that expertise dominates analysis. Sometimes this approach goes horribly wrong: recall, for example, Fred Goodwin's 2007 decision that RBS should buy ABN AMRO, based essentially on his gut feeling that the opportunity was comparable to the company's acquisition of NatWest bank a decade earlier. However, intuitive decision-making can also go spectacularly right, so the point here is not that you should always trust your rational mind, rather that you should become more conscious of the balance between the two sides.

Self-Control: Some Advice On Doing It Better

So how can we increase our capacity for self-control? This is one of the most fundamental questions in psychology, and there are several fields of thinking from Cognitive Behavioral Therapy to Psychotherapy that seek to answer it. I will focus here on self-control in the business world, but for interested readers there are applications to many aspects of life22.

I find the following metaphor useful. Karl Weick is a leading social psychologist based at the University of Michigan and during the 1990s he studied what he called “high-reliability organizations” such as aircraft carriers and nuclear power stations, where the tolerance for error was close to zero23. We all know that people get into behavioral routines at work, where they allow their subconscious mind to take over. Weick discovered that these high-reliability organizations had created mechanisms and norms of behavior that encouraged employees to transcend these routines. There was a “refusal to simplify” complex situations, a preoccupation with potential failure, and a fluid approach to organizational structure, with people apparently duplicating effort and moving between roles. These mechanisms helped to create “mindfulness” across the organization. In other words, they were designed to prevent employees from lapsing into mindless routines.

Many organizations in the extraction and manufacturing sector nowadays take these ideas about high reliability very seriously. I work with a large mining company and its approach to safety borders on the obsessive. The first 10 minutes of every meeting are devoted to safety issues, with attendees talking about recent safety incidents or offering tips to their colleagues. Conference calls with investors start with an update on safety, before the financial information is presented. This constant repetition is their way of keeping safety in the conscious part of the mind. By reminding themselves that safety matters, even when it doesn't, the employees of this company stay attentive and vigilant.

So how can you apply this logic to your own behavior? Recall the example of the pair of eyes placed above the coffee pot in the student residence. While operating at a subconscious level, this is the equivalent of the mining company's daily safety share – a constant reminder that we want to behave in an honest and ethical way. Dan Ariely, a leading figure in the world of behavioral economics, has done many experiments in this area, for example, asking people to sign their tax return before filling it in, to encourage them to disclose all their taxable earnings. His conclusion is simple but profound: “While ethics lectures have little to no effect, reminders of morality, right at the point where people are making a decision, appear to have an outsize effect on behavior.24”

The implications for you as a manager are straightforward: you can create simple stimuli, from a note on your diary, to a poster on your wall, to a conversation with a coach or mentor, prior to important meetings or conversations. These stimuli serve to remind you what is important and reduce your tendency to lapse back into routine or subconscious behaviors.

So which is it? Should you follow your gut or should you let the empirical analysis guide you? Well the answer, as always, is that it depends, but to make this facile statement a bit more useful, I propose another metaphor, which I call Managing by GPS (or Managing by SatNav for UK readers). Most drivers today have access to GPS technology, which provides a recommended route based on the available information. So when faced with a proposed route in a town you know well, do you follow it carefully? Or do you take a different route, because you believe you know better? I have been experimenting with myself here and I have quickly come to two conclusions: (1) if I always follow the GPS route, I occasionally get into trouble; (2) if I choose my own route, I occasionally come out ahead, but usually find myself lost or following an inferior route. These insights have led me to the following strategy: whenever I believe I know a better route than the one the GPS is suggesting, I ask myself, on what basis? If I know there has been an accident, or bad traffic, things the GPS cannot possibly be factoring in, then I go with my choice. However, if I cannot make a rational case to myself, then I (reluctantly) follow the GPS advice.

Hopefully the lesson from this metaphor is clear: many of your decisions as a manager are based on the equivalent of a GPS route – a report or a proposal that provides the best possible advice on the basis of the readily available data. It is your prerogative to overturn the advice you receive, but before doing so you should justify – to yourself – the basis for your judgment. Unless you can find an explanation, based on your personal experience and breadth of knowledge, you are better advised to stick to the proposed course of action.

The world of fund management provides a nice example of this. As a fund manager, it is tempting to follow your gut, perhaps because you have been successful with a particular strategy before, perhaps because you are being swayed by those around you. However, there is mounting evidence that persistent success in fund management comes from a highly rational approach, built around an individual's area of deep expertise and a careful monitoring of hit-rates (how many picks ended up making money?) and win–loss ratios (did the winners offset the losers?). As Simon Savage of MAN Group (a UK investment company) observes, “It is possible to detect and progressively control inherent biases. This can be facilitated through an objective feedback process, which helps to nurture investment talent and improve the quality of decision making over time.25” In other words, even a highly subjective activity such as investing can benefit from a data-driven approach, as a way of overcoming our inherent biases.

Overcoming Our Natural Instincts

The world of business is filled with managers like yourself who are seeking to become more effective in their work. However, the evidence suggests the gap between what we want to achieve and what we are able to achieve is as big as ever. I spend a lot of time working with companies on these issues and one of the interventions I often get involved in is small-scale experiments, such as the If insurance one at the beginning of this chapter. Very often, the experiment is a success, but the real insight ends being: So why don't we just do this stuff anyway?

Lack of time and resources is only part of the story. I think the underlying problem is that so many aspects of good management involve going against our natural instincts. We have to work very hard to overcome our need for control and our bias for self-aggrandizement. We also have to be very self-aware to realize when our behavioral flaws are getting in the way. There are no simple solutions here, but hopefully this chapter has offered some useful tips and tricks to help you be more aware of your own shortcomings and more thoughtful about ways of overcoming them.

Of course, even the most thoughtful and deliberate managers can still see their efforts come to nothing, if they cannot rely on the rest of the organization to support them. We would like to believe our organizations were designed to help us. Unfortunately, that is only partially true. Even the best-functioning organizations have flaws and pathologies that often get in our way. So good management isn't just about understanding our own limitations, it is also about understanding our organization's limitations and what we can do to transcend them. That is the subject of the next chapter.

Notes

1 This story was first described in: Birkinshaw, J.M. and Caulkin, S., Business Strategy Review, Winter 2012.

2 Kahneman, D., Thinking Fast and Slow, Allen Lane, 2011, page 20.

3 Nicholson, N, Evolutionary psychology: toward a new view of human nature and organizational society, Human Relations, 2007, 50(9): 1053–1078.

4 This notion of management as an unnatural act has been around for a while. See, for example: Suters, E.T., The Unnatural Act of Management, 1992; Boyatzis, R.E., Cowen, S.S., and Kolb, D.A., Innovation in Professional Education: Steps on a Journey from Teaching to Learning, Jossey-Bass, 1995, page 50.

5 Hurst, D.A., The New Ecology of Leadership, Columbia Business School Press, 2011, page 247.

6 The notion of a signature process was developed by my colleague Lynda Gratton. See: Gratton, L. and Ghoshal, S., Beyond Best Practice, Sloan Management Review, 2005, 46(3): 49–57.

7 Ray Dalio's management model has been discussed quite frequently in the media. See, for example: Cassidy, J, Mastering the Machine, The New Yorker, July 25, 2011. Dalio's principles can be found at: http://www.bwater.com/Uploads/FileManager/Principles/Bridgewater-Associates-Ray-Dalio-Principles.pdf.

8 This is a research study I am conducting in collaboration with Jordan Cohen at PA Consulting. At the time of writing this book, we had not completed the research.

9 Svenson, O., Are we all less risky and more skillful than our fellow drivers?, Acta Psychologica, 1981, 47(2): 143–148; Zuckerman, E.W. and Jost, J.T., What makes you think you're so popular? Self evaluation maintenance and the subjective side of the “Friendship Paradox,” Social Psychology Quarterly, 2001, 64(3): 207–223.

10 Tetlock, P.E., Expert Political Judgement: How Good is it?, Princeton University Press, 2005.

11 Cooper, A.C., Woo, C.Y. and Dunkelberg, W.C., Entrepreneurs' perceived chances for success, Journal of Business Venturing, 1988, 3: 97–108; Astebro, T., Assessing the commercial viability of new ventures, Canadian Investment Review, Spring 2003, pages 18–25.

12 Malmendier, U. and Tate, G., Does overconfidence affect corporate investment? CEO overconfidence measures revisited, European Financial Management, 2005, 11(5): 649–659.

13 Nicholson, N., Personality and entrepreneurial leadership: a study of the heads of the UK's most successful independent companies, European Management Journal, 2008, 16: 529–539.

14 Cassidy, J., Mastering the Machine, New Yorker Magazine, July 25, 2011.

15 Harford, T., Adapt: Why Success Always Starts with Failure, Abacus Books, 2011.

16 Kahneman, D., op cit, page 55.

17 Vohs, K., The psychological consequences of money, Science, 314: 1154–1156.

18 Danziger, S., Levav, J., and Avniam-Pesso, L., Extraneous factors in judicial decisions, Proceedings of the National Academy of Science, 2011, 108: 6889–6892.

19 Meehl, P.E., Clinical versus statistical prediction: a theoretical analysis and a review of the evidence, University of Minnesota Press, 1954.

20 This paper by Orley Ashenfelter is available at: http://www.terry.uga.edu/economics/docs/ashenfelter_predicting_quality.pdf.

21 Weick, K.M. and Guinote, A., When subjective experiences matter: power increases reliance on the ease of retrieval, Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 2008, 94: 956–970.

22 See, for example: Duhigg, C., The Power of Habit, William Heinemann, London, 2012.

23 Karl Weick has written many academic articles on “High Reliability Organisations.” The best practical way of getting to grips with his ideas is his book: Weick, K.E. and Sutcliffe, K., Managing the Unexpected, John Wiley & Sons, Ltd, 2007.

24 See Ariely, D., Predictably Irrational, Harper, 2008. Dan Ariely also has a blog with all his latest ideas, and from which I took this quote: www.danariely.com.

25 Savage, S., Skill, luck and human frailty, GLG Views, from the company's website: www.glgpartners.com.