Welcome to Adobe Animate CC. We suspect you are here because you have seen a lot of the great stuff that Animate CC can do and it is now time for you to get into the game. We also suspect you are here because you discovered that Animate CC is more complex than you originally thought. The other reason you may be here is because you were a former Flash Professional user and you need to get a handle on this new stuff in relatively short order. Whatever your motivation, both authors have been in your shoes at some point in our careers, which means we understand what you are feeling. So instead of jumping right into the application . . . let’s go for walk.

What we’ll cover in this chapter:

Exploring the Animate CC interface

Using the Animate CC stage

Working with panels

Understanding the difference between a frame and a keyframe

Using frames to arrange the content on the stage

Using layers to manage content on the stage

Adding objects to the Library

Testing your movie

If you haven’t already, download the chapter files. They can be found at http://www.apress.com/us/book/9781484223758 .

These files are used in this chapter:

01_Magnify.fla (Chapter01/Exercise Files_CH01/Exercise/01_Magnify.fla)

02_Ad.fla (Chapter01/Exercise Files_CH01/Exercise/02_Ad.fla)

03_Timeline.fla (Chapter01/Exercise Files_CH01/Exercise/03_Timeline.fla)

04_Properties.fla (Chapter01/Exercise Files_CH01/Exercise/Properties.fla)

05_Layers.fla (Chapter01/Exercise Files_CH01/Exercise/Layers.fla)

06_MoonOverLakeNanagook.fla (Chapter01/ExerciseFiles_CH01/Exercise/Garden.fla)

Nanagook.mp3 (Chapter01/ExerciseFiles_CH01/Exercise/FliesBuzzing.mp3)

We are going to take a walk through the authoring environment—called the Animate CC interface—and point out the sights to give you an opportunity to play with some of the stuff we will be pointing out. By the end of the stroll, you should be fairly comfortable with this tool called Animate CC and have a fairly good idea of what tools you can use and how to use them as you start creating Animate CC movies.

As we go for our walk, we will also have a conversation that will help you understand the fundamentals of the creation of an Animate CC movie. Having this knowledge right at the start of the process will give you the confidence to build on what you have learned. So let’s start our walk right at the beginning of the process . . . the Start page.

Getting Started

A couple of seconds after you double-click the Application icon to launch Animate CC, the Start page, shown in Figure 1-1, opens. This page, which is common to all of the CC applications, is divided into six discrete areas.

Figure 1-1. The Start page

Open Recent Item: The documents listed are the ones opened recently. Provided you haven’t moved them to another location or deleted them, clicking one will open it. Clicking Open will let you browse for files not contained in the list.

Create New: The middle area is where you can open a variety of new documents. It is broken into three distinct sections for a reason: They reflect the three major document types you can create. In this book we will only be dealing with ActionScript 3.0 and HTML5 Canvas documents. HTML5 Canvas can use detailed artwork, graphics, animations, and practically everything else that can be created in Animate CC. The other choice is WebGL (Web Graphics Library) , which allows you to to render plug-in free graphics on any compatible browser. The two groups below it are for specific types of documents ranging from the code-only ActionScript 3.0 document to the three AIR plug-ins that allow you to package your Animate CC projects into apps. The final four types are specific code-based options.

You may have noticed that the name is officially WebGL (Preview). The current version of Animate CC only supports basic animations and has a limited set of interactivity features. Thus it is a work in progress.

Introduction: Each item here will launch a browser that takes you to a series of Animate CC tutorials that address the category you clicked.

Learn: This area provides you with a series of Animate CC help documents that will allow you to explore, in greater depth, topics and techniques aimed at the category you selected.

Templates: This category is a bit misleading. Double-clicking one of the choices actually opens the New from Template dialog box. The purpose of these templates is to give you the opportunity to dissect a variety of sample documents.

Adobe Exchange: Click this and you are taken to a web page that gives you the opportunity to purchase or download a variety of plug-ins and extensions for Animate CC.

Creating a New Animate CC document

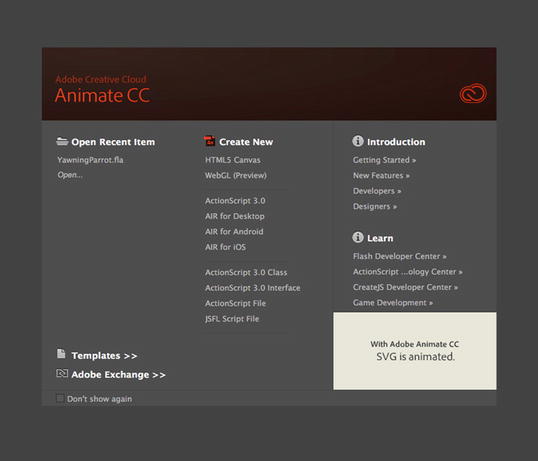

Let’s continue our stroll through Animate CC by creating a new Animate CC document. To do this, simply click the HTML5 Canvas button in the Create New area of the Start page. This opens the interface shown in Figure 1-2.

Figure 1-2. The Animate CC authoring environment

This interface is the feature-rich authoring environment that is the heart and soul of Animate CC. Let’s now step into that big white area on the screen and take a moment to look around. The stage, that large white area in the center of the screen, is where the action happens. A good way of regarding the stage in relation to Animate CC is this: if it isn’t on the stage, the user isn’t going to see it. There will be instances where this last statement is not exactly true, but we’ll get into those later in this book.

On the far-right edge of the screen is a set of tools that allow you to draw, color, and otherwise manipulate objects on the stage.

To the right of the stage are the panels. Panels are used to modify and manipulate whatever object you selected on the stage or to even add an object to the stage. These objects can be text, photographs, line art, short animations, video, or even interface elements called components. You can use the panels and the menus to change not only the characteristics of the objects but also how the objects behave on the stage. Panels can be connected to each other ( docked), or they can float freely in the interface (floating) and can be placed anywhere you like. To move a panel simply, click the Panel tab and drag it to a new location. If you see a blue line, the panel will dock to that location.

From our perspective, one of the more indispensable panels is the Properties panel. We’ll talk about this a little later, but as you become more comfortable with the application, this panel will become a very important place for you. In fact, we can’t think of any chapter in this book where we don’t refer to this panel.

At the bottom of the interface is the Timeline panel, which longtime Animate CC users simply refer to as the timeline. This is the place where the action occurs. As you can see, the timeline is broken into a series of boxes called frames. The best way of regarding frames is as individual frames of a film. When you put something on the stage, it will appear in a frame. If you want it to move from here to there, it will start in one frame and move to another position on the stage in another frame a little farther along the timeline. The box with the vertical red stem draped over the timeline is called the playhead. Its purpose is to show you the current frame being displayed. When an Animate CC movie is playing through a browser or being tested, the playhead is in motion, and the user is seeing the frame where the playhead is located. This is how things appear to move in Animate CC. Another thing you can do with the playhead is drag it across the timeline while you are creating the Animate CC movie. This technique is known as scrubbingthe timeline and has its roots in film editing.

Managing Your Workspace

As you may have surmised, the Animate CC authoring environment is one busy place, and if you talk to any Animate CC developer or designer, he or she will also tell you it can become one crowded place as well. As you start creating Animate CC projects, you will discover that screen real estate becomes a valuable commodity because it fills up with floating panels and other elements. Thus you need to know how to mange the panels. Here’s how:

Collapse panels: At the top of Panels area on the right side of the screen is an icon that looks like a double arrow (see Figure 1-3). Click it, and the panels will collapse and become icons. If you click the arrow above the panel, the Tools panel changes from a series of Tool icons to a single icon. The process is called panel collapse, and it is designed to free up screen space in Animate CC. There are three views for panels: fully expanded, partially collapsed showing the icon and panel name, completely collapsed to just the icon.

Figure 1-3. Panels can be collapsed to give you more screen space

Show collapsed panels as icons only: Sometimes you need the extra interface room taken up by the panel’s name. Roll the mouse pointer to the left or right edge of the panel strip. When the mouse pointer changes to a double-sided arrow, click and drag to expand and show the panel’s name, or shrink to the width of the icons in the strip.

Open and close drawers:Click an icon, and the contents of that panel will fly out, as shown in Figure 1-4. Click it again, and it will slide back. These panels that fly out and slide back are called drawers.

Figure 1-4. Click a panel icon, and the contents slide out. Click the icon again, and they slide in

Minimize panels: Another method of buying screen real estate is to minimize panels you aren’t using. Double-click the tab with the panel’s name, and the panel collapses upward. Double-click it again, and it expands to its original dimensions.

Close panels: Right-click (Windows) or Control+click (Mac) a panel, and select Close from the context menu. This not only closes the panel but also removes it from your workspace. To get it back, simply open the Window menu and click the name of the panel you closed to restore it.

Add panels to sets: A collection of panel icons, as shown in Figure 1-5, is called a panel set. To create a customized panel set, drag one panel icon onto another panel. When you release the mouse, the panel will expand to include the new panel added. To remove a panel from a set, just drag the panel icon to the bottom of the stack.

Figure 1-5. A typical panel set

To save your customized workspace, select Window ➤ Workspace ➤ New Workspace and enter a name for your custom workspace into the New Workspace dialog box. Click OK to add the workspace. If you want to delete one of your workspaces, select Window ➤ Workspace ➤ Manage Workspaces. When the Manage Workspaces dialog box opens, select the space to be deleted and click the Delete button.

Speaking of workspaces , at the top right of the Animate CC interface is a drop-down list of “prerolled” workspaces that came with the application. The default is Essentials. If you click and hold down that button, a drop-down list of the choices appears. If you want to return the workspace to its “out-of-the-box” look, select the Reset Essentials item in the menu.

Now that you have learned to become the master of the work environment, let’s take a look at how you can also become the master of your Animate CC document as we wander over to the Preferences and Properties areas of Animate CC.

Setting Document Preferences and Properties

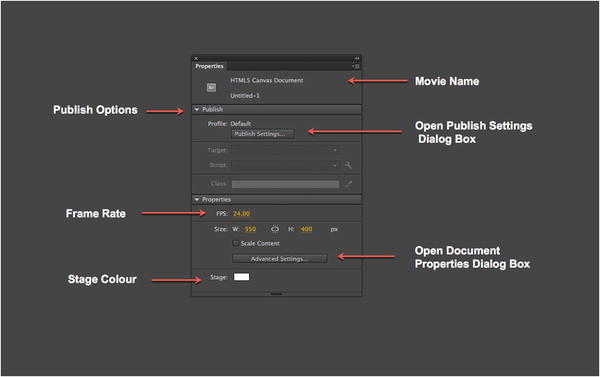

Managing the workspace is a fundamental skill, but the most important decision you will make concerns the size of the Animate CC stage and the space it will take up in the browser. That decision is based on a number of factors, including the type of content to be displayed and the items that will appear in the HTML document beside the Animate CC movie. These decisions all affect the stage size and, in many respects, the way the document is handled by Animate CC. These two factors are managed by the Preferences dialog box and the Document Properties panel .

Document Preferences

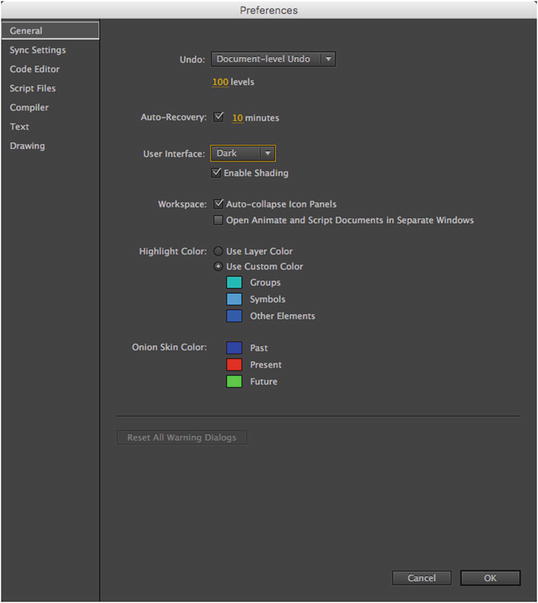

To access preferences, select Edit ➤ Preferences (Windows) or Animate CC ➤ Preferences (Mac). This will open the Animate CC Preferences dialog box. There is a lot to this dialog box, and we’ll explore it further at various points throughout this book. For now, we are concerned with the general preferences in the Category area of the window. Click General, and the window will change to show you the general preferences for Animate CC, as shown in Figure 1-6.

Figure 1-6. The General preferences can be used to manage not only the workspace but also items on the stage

If you examine the selections , you will realize they are fairly intuitive. You can change the interface from dark to light, how many Undo levels are available to you and even the colors that will be used to tell you what type of object has been selected on the stage.

Now that you know how to set your preferences, let’s take a look at managing a document’s properties. Click the Cancel button to close the Preferences dialog box. When it closes, let’s wander back to the stage and explore how a document’s properties are determined.

Document Settings

To access the Document Settings dialog box, use one of the following techniques:

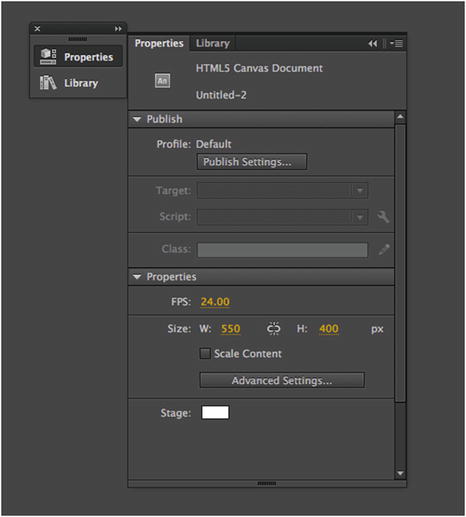

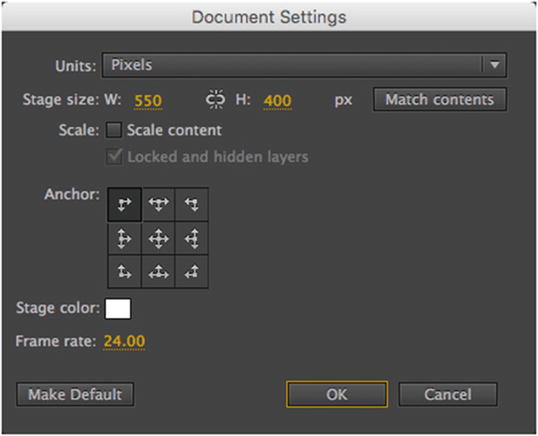

In the Properties panel, click the Advanced Settings button in the Properties area—not the Publish area. This will open the Document Settings dialog box shown in Figure 1-7.

Figure 1-7. Set the stage size through the Document Settings dialog box

Select Modify ➤ Document.

Press Ctrl+J (Windows) or Cmd+J (Mac).

Right-click (Windows) or Control+click (Mac) the stage and select Document Properties from the context menu.

As you have just seen, there are a number of methods you can use in Animate CC to obtain the same result. In this case, it is opening the Document Settings dialog box. Which one is best? The answer is simple: whichever one you choose.

Now that the Document Settings dialog box is open, let’s look around. The Dimensions input area is where you can change the size of the stage. Enter the new dimensions and press the Enter (Return) key. If you enter a value, you may need to press the the Enter or Return key twice. Once to accept the new entry and a second time to close the dialog box, or click the OK button, and the stage will change. The Match Contents button is commonly used to shrink the stage to the size of the content on the stage.

The Anchor area is not what you may think. Each selection determines how the stage will scale when the dimensions of the stage are changed, not the content.

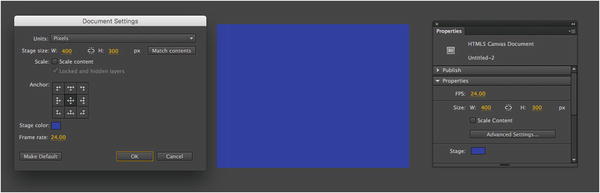

For example, if you change the Dimensions setting to a width of 400 pixels and height of 300 pixels, set the Background color option to #0033CC, select the Center anchor, and click OK, the stage will shrink to those dimensions and change color to the blue chosen. The changes, as shown in Figure 1-8, are also reflected in the Properties panel.

Figure 1-8. Changes made to the document properties are shown in the Properties panel

Zooming the Stage

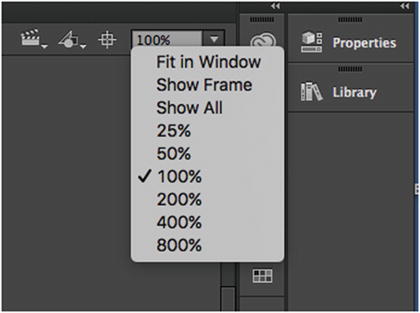

There will be occasions when you discover that the stage is a pretty crowded place. In these situations, you’ll want to be sure that each item on the stage is in its correct position and is properly sized. Depending on the size of the stage, this could be difficult because the stage may fill the screen area. Fortunately, Animate CC allows you to reduce or increase the magnification of the stage through a technique called zooming. (Note that zooming the stage has no effect on the actual stage size that you set in the Document Settings dialog box.)

To zoom the stage, click the Magnification drop-down menu near the upper-right corner of the stage. The drop-down menu shown in Figure 1-9 contains a variety of sizes ranging from Fit in Window to 800% magnification. For example, click the 400% option, and the stage will most likely fill your screen , as shown in Figure 1-10. Just keep in mind that you are not scaling the image on the stage. You are actually magnifying the stage and its contents. Click the 25% option, and you will see not only the stage but the entire pasteboard (that gray area surrounding the stage) as well.

Figure 1-9. Select a zoom level using the Magnification drop-down menu

Figure 1-10. Selecting a 400 percent zoom level brings you close to the action

If you want more zoom, you can get a lot closer than 800 percent. Select View ➤ Zoom In or View ➤ Zoom Out to increase the zoom level to 2000 percent. If you want a real bird’s-eye view of the stage, Zoom Out allows you to reduce the magnification level to 8 percent. For you keyboard junkies, Zoom In is Command/Ctrl+= and Zoom Out is Command/Ctrl+ -. If you are a control freak, you can enter your own value. Just keep in mind the maximum zoom level is 2000 percent, and the minimum zoom level is 8 percent.

If you want a side-by-side comparison in which one image is at 100 percent view and the other is at 400 percent or 800 percent, follow these steps:

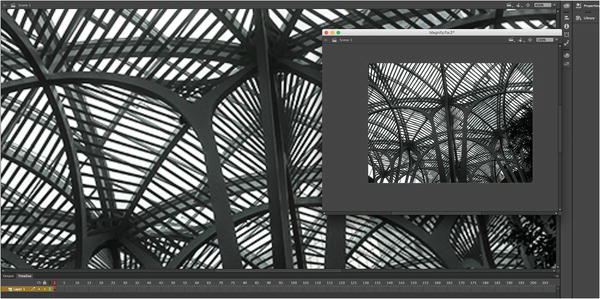

Open the Magnify.fla file in the Chapter 1 Exercise folder.

Select Window ➤ Duplicate Window. The current document will appear in a separate tab.

Set the new window’s magnification level to 400% and press the Enter key.

Undock the 100 percent window, as shown in Figure 1-11, and let it float.

Figure 1-11. Duplicating a window gives you a bird’s-eye view and a detailed view of your work simultaneously

Select the image in the floating window by clicking the image and dragging it around the stage. You will see that the zoomed-in version in the docked window also moves. This is a really handy feature if precise positioning of elements on the stage is critical.

Click each window’s close button to close the window. Don’t save the changes.

Exploring the Panels in the Animate CC Interface

At this point in our stroll through the Animate CC interface, you have had the chance to play with a few of the panels. We also suspect that by this point you have discovered that the Animate CC interface is modular. By that we mean that it’s an interface composed of a series of panels that contain the tools and features you will use on a regular basis, rather than an interface that’s locked in place and fills the screen. You have also discovered that these panels can be moved around and opened or closed depending on your workflow needs. In this section, we are going to take a closer look at the more important panels that you will use every day. They include the following:

The timeline

The Library panel

The Properties panel

The Motion Editor

The Tools panel

The Help panel

The Timeline

Here’s the secret behind how one becomes a proficient Animate CC designer: master the timeline, and you will master Animate CC.

When somebody visits your site and an animation plays, Animate CC treats that animation as a series of still images. In many respects, those images are comparable to the images in a roll of film or one of those flip books you may have played with when you were younger. The order of those images on the film or in the book is determined by their placement on the film or in the book. In Animate CC, the order of images in an animation is determined by the timeline.

The timeline, therefore, controls what the users see and, more importantly, when they see it. To understand this concept, let’s go for a walk in a Canadian forest while the leaves are falling from the trees.

At its most basic, all animation is movement over time, and all animation has a start point and an end point. The length of your timeline will determine when animations start and end, and the number of frames between those two points will determine the duration of the animation. As the author, you control those factors.

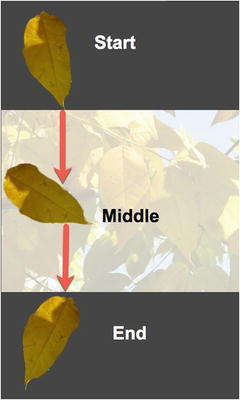

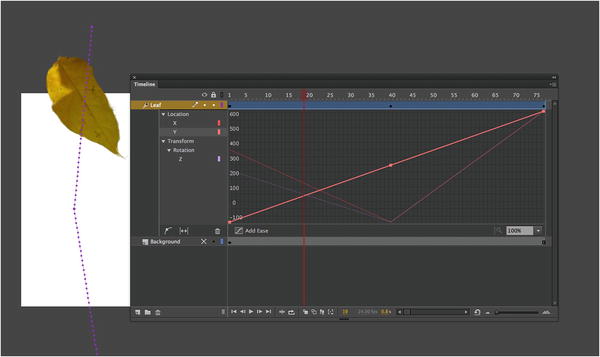

For example, Figure 1-12 shows you a simple animation. It is a leaf that falls from the top of the stage to the bottom. From this, you can gather that the leaf will move downward when the sequence starts and will continue to its final position at the bottom of the stage once it has twisted in the middle of the sequence.

Figure 1-12. A simple animation sequence

So, where does time come into play? Time is the number of frames between the start and middle or middle and end points in the animation. The default timing in an Animate CC movie—called frame rate—is 24 frames per second (fps). In the animation shown in Figure 1-13, the duration of the animation is 48 frames, which means it will play for 2 seconds. You can assume from this that the leaf’s middle location, where it twists, is the 24th frame of the timeline. If, for example, you wanted to speed up the animation, you would reduce the length of the timeline to 12 frames; if you wanted to slow it down, you would increase the number of frames to 72 or decrease the frame rate. If you want to see this animation, open the Timeline.html file in the O1_Complete folder.

Figure 1-13. Animation is a series of frames on the timeline

So much for a walk in the woods; let’s wander over to the timeline and look at a frame.

Frames

If you unroll a spool of movie film, you will see that it is composed of a series of individual still images. Each image is called a frame, and this analogy applies to Animate CC.

When you open Animate CC, your timeline will be empty, but you will see a series of rectangles—these are the frames. You may also notice that these frames are divided into groups. Most frames are gray, and every fifth frame is numbered (see Figure 1-14), just to help you keep your place. Animate CC movies can range in length from 1 to 16,000 frames, although an Animate CC movie that is 16,000 frames in length is highly unusual.

Figure 1-14. The timeline is nothing more than a series of frames

A frame shows you the content that is on the stage at any point in time. The content in a frame can range from one object to hundreds of objects, and a frame can include audio, video, code, images, text, and drawings either singly or in combination with each other.

When you first open a new Animate CC document, you will notice that frame 1 contains a hollow circle. This visual clue tells you that frame 1 is waiting for you to add something to it. Let’s look at a movie that actually has something in the frames and examine some of the features of frames:

Open the 02_Ad.fla file located in the Chapter 1 Exercise folder. When the file opens, you will see a basic banner ad for a local garden center. There is a text box, in frame 1, sitting at the bottom of the stage and a logo at the top. You should also note the solid dot in the background, TextBox, and Logo layers. This indicates that there is content in Frame 1 of each of those layers The empty layer above them has a hollow dot, which indicates there is no content in that frame.

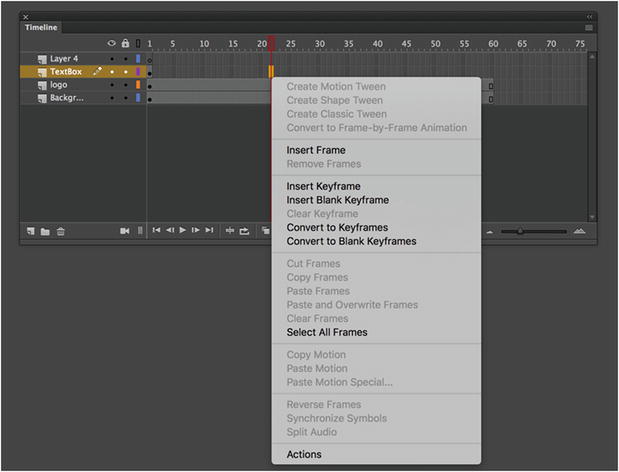

Place the mouse pointer on any frame of the timeline and right-click (Windows) or Control+click (Mac) to open the context menu that applies to frames (Figure 1-15).

Figure 1-15. The context menu that applies to frames on the timeline

As you can see, quite a few options are available to you . They range from adding motion to the timeline to adding actions (code blocks) that control the objects in the frame. We aren’t going to dig into what each menu item does just yet, but rest assured, by the time you finish this book, you will have used each menu item.

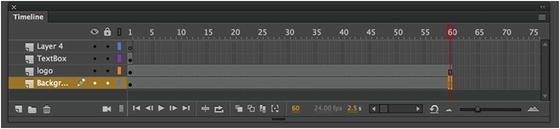

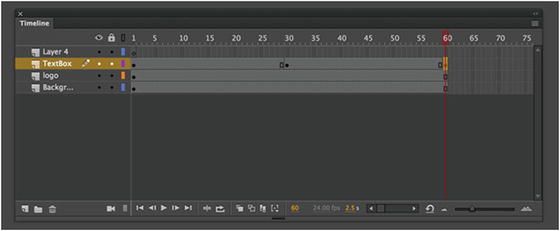

Place the mouse pointer at frame 30 of the TextBox layer, open the context menu, and select Insert Keyframe. Repeat this step at frame 60 as well. What you will notice is that the timeline changes to the series of gray frames and three black dots, as shown in Figure 1-16. These gray frames represent a span of frames separated by keyframes.

Figure 1-16. The timeline contains three keyframes

If you prefer to use the keyboard, place the mouse pointer at frame 30 and press F5. With that frame selected, press F6. The F5 command adds a frame, and F6 converts the selected frame to a keyframe. If you just want to add a keyframe, select frame 30 and press F6.

An obvious question at this point is, “So, guys, what’s a keyframe?” Remember when we talked earlier about animations and how they had a start point and an end point? In Animate CC, those two points are called keyframes; any movement or changes can only occur between keyframes. In Animate CC, there are two types of keyframes: those with stuff in them (indicated by the solid dot shown in frame 1 of Figure 1-16) and those with nothing in them. The latter are called blank keyframes, and they are shown as frames with a hollow dot. The first frame in any layer, until you add something to that frame, is always indicated by a blank keyframe.

To navigate to specific frames in the timeline, you drag the playhead to the frame. It is the red rectangle with the line coming out of it.

Move the playhead to frame 1 and drag the TextBox to the left of the stage and on to the pasteboard.

Drag the playhead to frame 30, use the Selection tool to click the TextBox on the stage, and move the TextBox over to the middle of the stage. As you moved the object, you may have noticed there was a “ghosted” version of the leaf on the screen. This feature was introduced in Flash Professional CS4. It gives you a reference to the starting position of the motion.

As mentioned earlier in the chapter, the technique of dragging the playhead across the timeline is called scrubbing. As you scrub across the timeline, you will also see the values in the Current Frame and Elapsed Time areas at the bottom of the timeline change. This is quite useful in locating a precise frame number or a specific time in the animation.

Drag the playhead to the keyframe in frame 60 and drag the object to the bottom-right edge of the stage.

Scrub the playhead across the stage. The TextBox doesn’t do much other than “pop” to its new positions as you encounter the keyframes. Let’s fix that right now.

Right-click (Windows) or Control+click (Mac) between the first two keyframes of the TextBox layer and select Create Classic Tween from the context menu. An arrow will appear between the two keyframes. Scrub across the timeline again, and the object’s movement is much smoother. Repeat this step for the next two keyframes.

A tween is how simple animations are created in Animate CC. Animate CC looks at the locations of the objects between two keyframes, creates copies of those objects, and puts them in their positions in the frame. If you scrub through your timeline, you will see that Animate CC has placed copies of the object in frames 2 through 30 and in frames 31 through 60 and then puts them in their final positions to give the illusion that the TextBox is moving.

That was interesting , but we suspect you may be wondering, “Okay, guys, do tweens work only for stuff that moves?” Nope. You can also use tweens to change the shapes of objects, their color, their opacity, and a number of other properties. We’ll get to them later on in the book.

Drag the playhead to frame 30 and click the TextBox on the stage. Drag it toward the center of the bottom of the stage. If you scrub through the timeline, you will see it move quite a distance to the right. This tells you that you can change an animation by simply changing the location of an object in a keyframe.

You may have noticed that the logo vanishes. Let’s fix that. Right-click on frame 60 of the Logo layer and select Insert Frame from the Context menu. This technique is ideal for objects that don’t move.

Close the file without saving it.

Using the Motion Editor

As you get deeper into working with Animate CC, you will find there is a reason why the Timeline and Motion Editor are inseparable: motion is created in the timeline and manipulated in the Motion Editor. Make a change in one, and it is instantly reflected in the other.

In previous versions of Animate CC, the Property Inspector, which is now the Properties panel, could be used to change the properties of an animation. This would include techniques such as “ramping” the speed of an animation, called easing, or even changing how an animation occurs such as adding or removing rotation. This is still true for shape tweens and classic tweens, but the true power of motion is realized in the Motion Editor which, in Animate CC, is no longer a separate panel on the timeline.

Although we are going to get deeper into using these features later in this book, now would be a good time to stroll over to it and take a peek. Open the 03_Timeline.fla file. When the file opens, the first thing you will notice is there is an icon beside the layer name. This “zooming square ” icon indicates the layer is a tween layer. The term tween indicates that something is changing at some point in the layer—we’ll get into tweening in more detail later. The other thing you may have noticed is that there are no arrows between the keyframes. The tween span is indicated in blue, and because of the icon, the use of the arrow is not necessary. The dotted line you see on the stage indicates a tween path.

If you are an After Effects user, you may be looking at that tween path and thinking, “Nah, it can’t be!” Yes, it is a motion path, and just like with an After Effects motion path, you can adjust that path by clicking and dragging one of the dots. Each dot represents a frame of the animation.

Drag the playhead across the timeline, and you will see the leaf gently tumble downward as you move the playhead from left to right. To see the Motion Editor, as shown in Figure 1-17, right-click anywhere on the Leaf timeline and select Refine Tween from the Context menu or simply double-click anywhere on the timeline. The Motion Editor shows you what properties have changed between the keyframes. In this case, it is Location and Rotation.

Figure 1-17. A motion layer, tween path, and the Motion Editor

The horizontal scale is time and the vertical scale shows you the property change of that object over time. Each line on the graph is color-coded and reflects a particular property change. For example, the Motion Editor is showing the Y motion (Downward) that starts just over 100 pixels above the stage—thus the negative value—and, over the 75 frames of the timeline, stops about 600 pixels below the top of the stage. Right in the middle is another keyframe.

Time for a history lesson. Back in 2000, one of us attended FlashForward. That event is regarded by many of the old Animate CC hands as being Animate CC’s “Woodstock .” It was at this conference that Adobe introduced LiveMotion. LiveMotion used the same timeline as the Motion Editor. At the time, we (and many people at the conference) thought the timeline was a “sweet” idea. Eight years later—three years after it purchased Macromedia (which owned Flash)—Adobe added this feature and it is now in Animate CC.

See those triangles beside the property names in Figure 1-17? If you click one, it rotates down, and the area is revealed. Those triangles are called twirlies, and the term used to describe clicking one of them to reveal the contents of the area is named “Twirl Down”. We will be using these terms quite extensively when we talk about the Motion Editor.

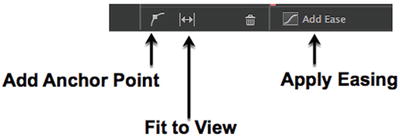

At the bottom of the Motion Editor there are four icons, as shown in Figure 1-18. They have a specific purpose:

Add Anchor Point: When you select this and click anywhere on one of the graph lines, you are adding a new keyframe.

Fit to View: Click this and the Motion Editor grows or shrinks.

Trash Can: This one is dangerous. Click it and you remove the tween for the selected property.

Apply Easing: Click this and you can apply a number of “eases” designed to give motion a more natural feel.

Figure 1-18. You can manage the look of the Motion Editor

The Properties Panel

We have been mentioning the Properties panel quite a bit to this point, so now would be a good time to stroll over to it and take a closer look. Before we do that, let’s go sit down on the bench over there and discuss a fundamental concept in Animate CC: everything has properties.

What are properties? These are the things objects have in common with each other. Tom and Joseph share the Author property of this book. We are both males. We both have a common language property, English, but we also have properties we don’t share. For example, our location properties are Denver and Toronto. Joseph has longer hair than Tom. At our most basic, we are humans on the planet Earth. In Animate CC terms, though, we are objects on the stage. Click the Joseph object, and you will instantly see that, even though he and Tom share similar properties, they also have properties that are different. The properties of any object on the Animate CC stage will appear in the Properties panel, and best of all, any properties appearing in the panel can be changed.

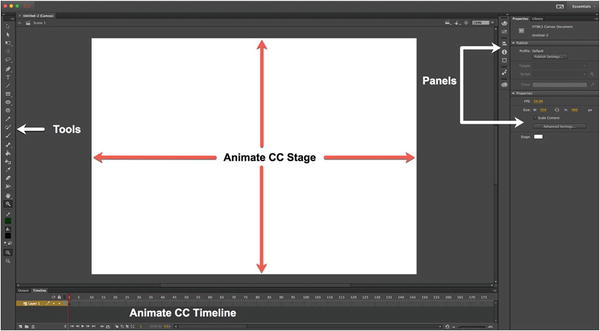

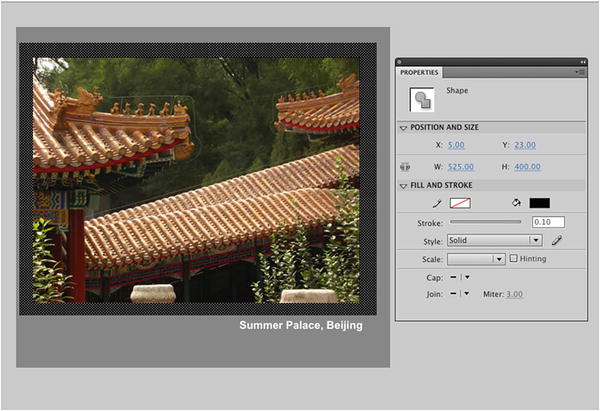

The panel, as shown in Figure 1-19, is positioned, by default, to the right of the screen. You can move it elsewhere on the screen by simply dragging it into position and releasing the mouse. There are locations on the screen where you will see a shadow or darkening of the location when the panel is over it. This color change indicates that the panel can be docked into that location. Otherwise, the panel will “float” above the screen.

Figure 1-19. The Properties panel

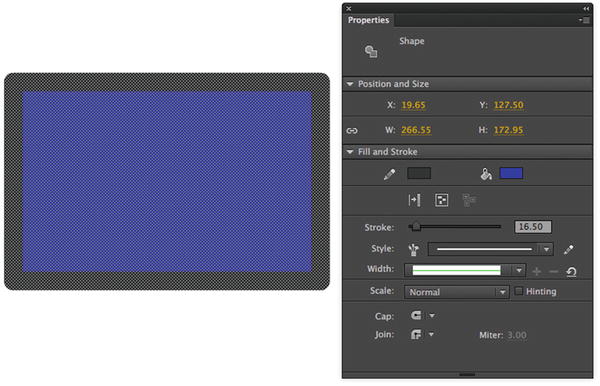

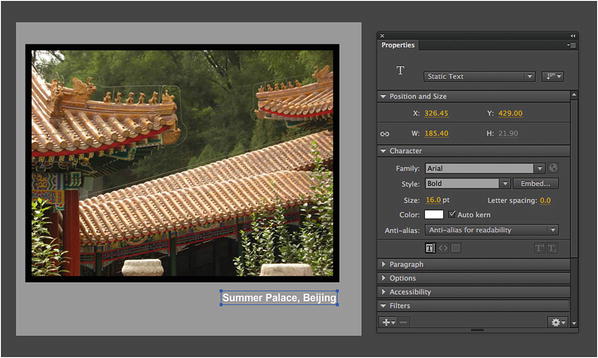

When an object is placed on the stage and selected, the Properties panel will change to reflect the properties of the selected object that can be manipulated. For example, in Figure 1-20, a box has been drawn on the stage. The Properties panel shows you the type of object that has been selected and tells you that the stroke and fill colors of the object can also be changed. In addition, you can change how scaling will be applied to the object and the treatment of the red stroke around the box.

Figure 1-20. The Properties panel changes to show you the properties of a selected object that can be manipulated (in this case, the size, location, and stroke and fill properties of the box on the stage)

Let’s experiment with some of the settings in the Properties panel:

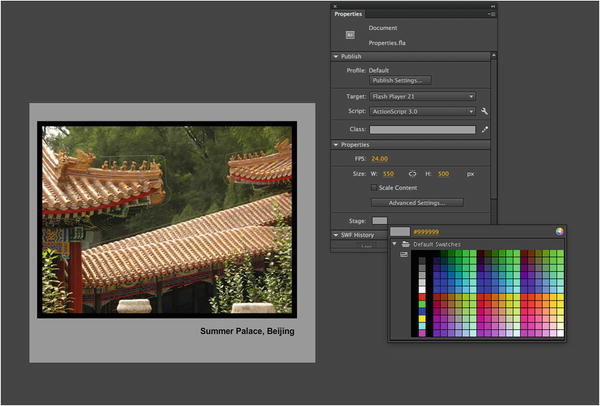

Open the file named 04_Properties.fla in the Exercise folder. When the file opens, you will see an image of the Summer Palace in Beijing over a black background and the words Summer Palace, Beijing at the bottom of the stage.

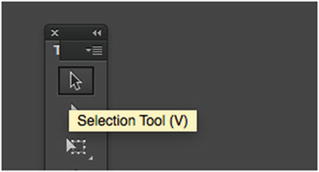

In the Tools panel, click the Selection tool , which is the solid black arrow at the top of the Tools panel (Figure 1-21).

Figure 1-21. Click a tool or use the keyboard to select it

Clicking tools is one way of selecting them. Another way is to use the keyboard. When you roll the mouse pointer over a tool, you will see a tooltip containing the name of the tool and a letter. For example, the letter beside the Selection tool is V. Press the V key, and the Selection tool will be highlighted in the Tools panel.

Using the Selection tool, click once in the white area of the stage. The Properties panel will change to show you that you have selected the stage and can change its color.

In the Properties panel, click the Background Color chip to open the Color Picker, as shown in Figure 1-22. Click the medium gray on the left (#999999), and the stage will turn gray. You have just changed the color property of the stage.

Figure 1-22. Color and stage dimensions are properties of the stage

Click the text. The Properties panel will change to show you the text properties, as shown in Figure 1-23, that can be changed. Click the color chip to open the Color Picker. When it opens, click the white chip once. The text turns white.

Figure 1-23. Color is just one of many text properties that can be manipulated

Click the black box surrounding the image. The Properties panel will change to tell you that you have selected a shape and that the fill color for this shape is black. It also lets you know that there is no stroke around the shape. In the Position and Size areas are four numbers that tell you the width, height, and X and Y coordinates of the shape on the stage. Select the Width value and change it from 500 to 525. Change the Height number from 380 to 400. Finally, change the X and Y values for the selection to 5 and 23, as shown in Figure 1-24. Each time you make a change, the selected object will get wider or higher.

Figure 1-24. The size and the location of selections can also be changed in the Properties panel

If you are an After Effects user, then seeing properties as links (or, as they are known in Animate CC, hot text) is not new. If you want to quickly change any value, simply click and drag a value to the left or the right. As you drag, the numbers will change, and the selected object on the stage will reflect these new values.

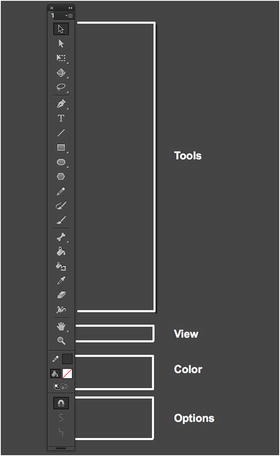

The Tools Panel

The Tools panel, as shown in Figure 1-25, is divided into four major areas:

Tools: These allow you to create, select, and manipulate text and graphics placed on the stage.

View: These allow you to pan across the stage or to zoom in on specific areas of the stage.

Colors: These tools allow you to select and change fill, stroke, and gradient colors.

Options: This is a context-sensitive area of the panel. In many ways, it is not unlike the Properties panel. It will change depending on which tool you have selected.

Figure 1-25. The Tools panel

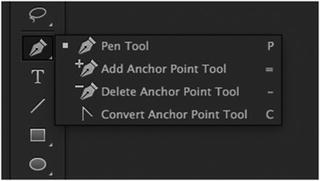

If there is a small down arrow in the bottom-right corner of a tool , this indicates additional tool options. Click and hold that arrow, and related tools will appear in a drop-down menu, as shown in Figure 1-26.

Figure 1-26. Some tools contain extra tools , which are shown in a drop-down list

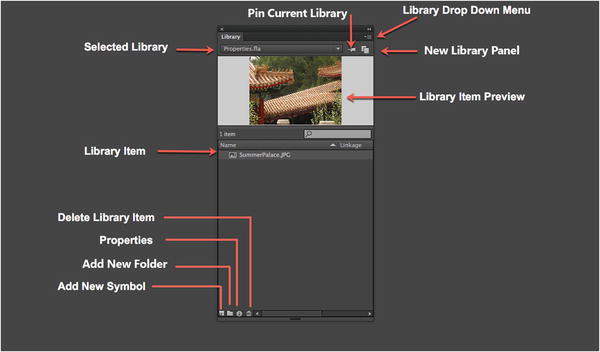

The Library Panel

The Library panel is one of those features of the application that is so indispensable to Animate CC developers and designers that we simply can’t think of anybody who doesn’t use it . . . religiously.

In very simple terms, it is the place where content, including video and audio, that is used in the movie is stored for reuse later in the movie. It is also the place where symbols and copies of components that you may use are automatically placed when the symbols are created or the components are added to the stage.

Let’s wander over to the Library and take a look. If the Properties.fla file isn’t open, open it now. Click the Library icon on the right side of the screen, or click the Library tab if the panel isn’t collapsed. The Library will fly out, as shown in Figure 1-27. Inside the Library, you will see that the Summer Palace image is actually a library asset. Drag a copy of the image from the Library to the stage. Leave it selected and press the Delete key. Notice that the image on the stage disappears, but the Library item is retained. This is an important concept. Items placed on the stage are, more often than not, instances of the item and point directly to the original in the Library.

Figure 1-27. The Library panel

To collapse the Library panel, click the stage. Panels, opened from icons, are configured to collapse automatically. If, for some reason, you want to turn off autocollapse, select Edit ➤ Preferences (Windows) or (Animate CC ➤ Preferences) to open Preferences. Click General and deselect Auto-Collapse Icon Panels when the preferences open. Another way of opening and closing the Library is to press Ctrl+L (Windows) or Cmd+L (Mac).

Creative Cloud Library

If you are using Adobe Animate CC then you also have a Creative Cloud account. Your Creative Cloud account lets you create a Library of assets from many of the Creative Cloud Desktop and Mobile apps. For example, you can create personal and shared libraries to keep track of logos, icons for web layouts, video clips, or your go-to brushes and color themes for illustrations. Your Library items are automatically synced to your Creative Cloud account, so you can work with them wherever you are, even if you're offline.

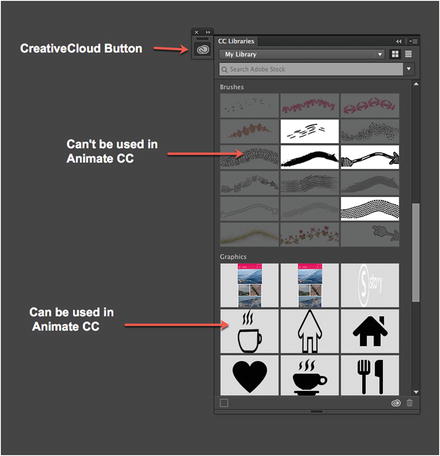

Your Creative Cloud library is available to you in Animate CC. To access it and use the items in your personal or team’s Creative Cloud Library, click the Creative Cloud panel icon in the panels. As shown in Figure 1-28, your panel opens and you can drag items from it to the Animate CC stage. Items that can’t be used in Animate CC are grayed out and items that can be used in Animate CC are lit up.

Figure 1-28. The Creative Cloud Library panel

Using Layers

The next stop on our walkabout is found under the stage: the layers feature of the timeline . There are a few things you need to know regarding layers:

You can have as many layers in an Animate CC movie as you need. They have no effect on the file size.

Use layers to manage your movie. Animate CC movies are composed of objects, media, and code, and it is a standard industry practice to give everything its own layer. This way, you can easily find content on a crowded stage. In fact, any object that is tweened must be on its own layer.

Layers can be grouped. Layers can be placed inside a folder, which means you can, for example, have a complex animation and have all the objects in the animation contained in their own layers inside a folder.

Layers stack on top of each other. For example, you can have a layer with a box in it and another with a ball in it. If the ball layer is above the box layer, the ball will appear to be in front of the box.

Name your layers. This is another standard industry practice that makes finding content in the movie very easy.

Screen real estate is always at a premium. If you need to see more of the stage, double-click the Timeline tab to collapse the layers. Double-click the Timeline tab again, and the layers are brought back.

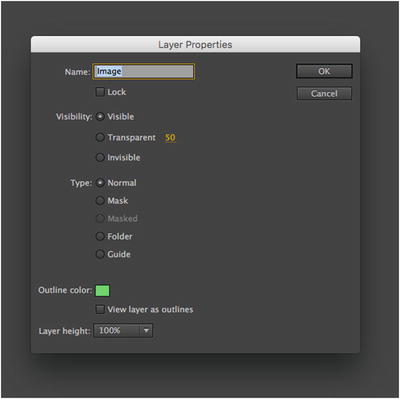

Layer Properties

Layers can also be put to very specific uses, and this is accomplished by assigning one of five layer properties, as shown in Figure 1-29, to a layer. Although they are called properties, they really should be regarded more as layer modes than anything else. We will be covering these in great depth in Chapters 3, 7, and 8, which focus on animation, but this is a good place to start learning where they are and what they do. The modes, accessed by right-clicking (Windows) or Control+clicking (Mac) a layer name and clicking Properties, are as follows:

Normal layer: This is the layer you have been working with at this point in the book. Objects on these layers are always visible, and motion is more or less governed by the Motion Editor. You can always identify a normal layer; its icon looks like a folded sheet of paper.

Mask layer: The shape of an object on a masking layer is used to hide anything outside the shape and reveals only whatever is under the object. For example, place an image on the stage and add a box in the layer above it. If that layer is a masking layer, only the pixels of the part of the image directly under the box will be seen. The icon for a mask layer is a square with an oval in the middle of it.

Masked layer: If you have a mask layer, you will also have one of these. Like Siamese twins, mask layers and masked layers—any layer under a mask—are joined together. The icon for a masked layer looks like a folded sheet of paper facing the opposite direction as the icon for a normal layer. In addition, the layer name for a masked layer is indented.

Folder layer: The best way of thinking of this mode is as a folder containing layers. They also provide quick access to layer groupings you may create. The icon for a folder layer is a file folder with a twirlie. Click the twirlie, and the layers in the folder are revealed. Click the twirlie again, and the layers folder collapses, hiding the layers.

Guide layer: A guide layer contains shapes, symbols, images, and so on, that you can use to align elements on other layers in a movie. These things are handy if you have a complex design and want a standard reference for the entire movie. What makes guide layers so important is that they aren’t rendered when you publish the animation. This means, for example, that you could create a comprehensive design (or comp) of the Animate CC stage in Photoshop CC, place that image in a guide layer, and not have to worry about an overly large set of files being published and bloating the project with unnecessary file size and download time. The icon for a guide layer is a T-square.

Figure 1-29. The Layer Properties panel

By default, Animate CC omits layers that are hidden—we get into hiding layers in a couple of minutes—when the file is eventually published.

Creating Layers

Let’s start using layers. Here’s how:

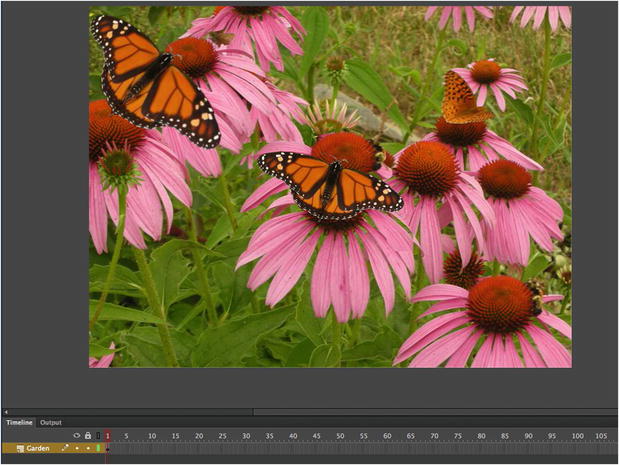

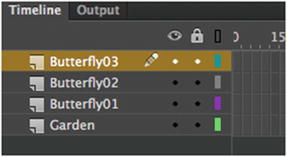

Open the 05_Layers.fla document. When it opens, you will see the garden and a couple of butterflies, as shown in Figure 1-30. If you look at the timeline, you could logically assume this is a simple photograph sitting on a single layer named Garden.

Figure 1-30. We start with what appears to be a photograph of flowers and butterflies

Open the Library. You will notice that there is an object named Butterfly contained in the Library. That object is a movieclip. We’ll get into movieclips in a big way in Chapter 3.

Click the keyframe in the Garden layer . Three objects—the two Monarch butterflies and the image—are selected. What you have just learned is how to select everything on a layer. Click the pasteboard to deselect the objects.

Each object should be placed on its own layer. Click the New Layer button—it looks like a page with a turned-up corner—directly under the Garden layer strip. A new layer, named Layer1, is added to the timeline.

Select the Garden layer by clicking it and add a new layer. Notice how the new layer is placed between Garden and Layer 1. This should tell you that all new layers added to the timeline are added directly above the currently selected layer. Obviously, Layer 2 is out of position. Let’s fix that.

Drag Layer 2 above Layer 1 and release the mouse. Now you know how to reorder layers and move them around in the timeline. Layers can be dragged above or below each other.

Add a new layer, Layer 3. Hold on—we have four layers and three objects. The math doesn’t work. That new layer has to go.

Select Layer 3 and click the Trash Can . Layer 3 will now be deleted, and now you know how to get rid of an extra layer.

Double-click the Layer 1 layer name to select it. Rename the layer Butterfly. Now that you know how to rename a layer, select File ➤ Revert to revert the file to its original state. It’s now time to learn how to put content on layers.

Adding Content to Layers

Content can be added to layers in one of two ways:

Directly to the layer by moving an object from the Library to the layer

From one layer to another layer

Let’s explore how to use the two methods to place content into layers:

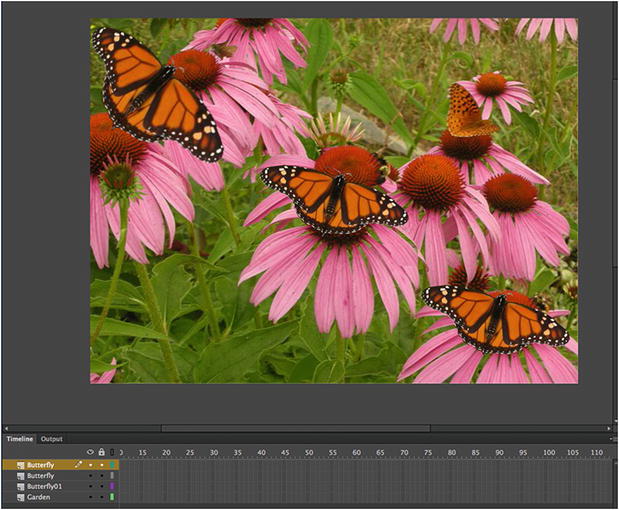

Create a new layer, name it Butterfly01, and drag the Butterfly movieclip from the Library to cover the flower, as shown in Figure 1-31, in the bottom-right corner of the stage. The hollow dot in the layer will change to a solid dot to indicate that there is content in the frame. When moving objects from the Library to the stage, be sure to select the layer, sometimes called a target layer, before you drag and drop. This way, you can prevent the content from going in the wrong layer. Let’s now turn our attention to getting the two other butterflies into their own layers.

Figure 1-31. Objects can be dragged directly from the Library and added to specific layers

With the Shift key held down, click the two butterflies in the center and upper-left corner of the stage. This will select them, and the blue box around each one indicates they are movieclips.

Select Modify ➤ Timeline ➤ Distribute to Layers, or press Ctrl+Shift+D (Windows) or Cmd+Shift+D (Mac). The butterflies will appear in the new Butterfly layers that appear under the Garden layer. Rename these layers Butterfly02 and Butterfly03, and move them, as shown in Figure 1-32, above the Butterly01 layer.

Figure 1-32. Multiple selections can be placed in their own layers using the Distribute to Layers command

The next technique addresses a very common issue encountered by Animate CC designers: taking content from one layer and placing it in the exact same position in another layer. This is an issue because you can’t drag content from one layer to another.

Click the Butterfly movieclip in the center of the stage and press Ctrl+X (Windows) or Cmd+X (Mac) to cut the selection out of the layer.

With the layer still selected in the timeline, select Edit ➤ Paste in Place. A copy of the butterfly will appear exactly where you cut it.

Whatever happened to a simple paste command in the Edit menu? The Paste in Center command replaces it. It has always been a fact of Animate CC life that any content on the clipboard is pasted into the center of the stage. The name-Paste in Place-simply acknowledges this.

Showing/Hiding and Locking Layers

We are sure the three icons—an eyeball, a lock, and a hollow square (shown in Figure 1-33)—above the layers caught your attention. Let’s see what they do.

Figure 1-33. The Layer Visibility, Lock, and Show All Layers As Outlines icons. Note the Pencil icon in the Butterfly03 layer, which tells you that you can add content to that layer.

Click the eyeball icon. Notice that everything on the stage disappears, and the dots under the eyeball in each layer change to an x. This eyeball is the Layer Visibility icon, and clicking it turns off the visibility of all the content in the layers. Click the icon again, and everything reappears. This time, select the Butterfly02 layer and click the dot under the eyeball. Just the butterfly in the center of the stage disappears. What this tells you is that you can turn off the visibility for a specific layer by clicking the dot in the visibility column.

When you click a layer, you may notice that a pencil icon appears on the layer strip. This tells you that you can add content to the layer. Click the Butterfly03 layer, and you’ll see the pencil icon. Now, click the dot under the lock in the Butterfly02 layer. The lock icon will replace the dot. When you lock a layer, you can’t draw on it or add content to it. You can see this because the pencil has a stroke through it. If you try to drag the Butterfly movieclip from the Library to the Butterfly02 layer, you will also see that the layer has been locked because the mouse pointer changes from an arrow to a circle with a line through it. Also, if you try to click the butterfly on the stage, you won’t be able to select it. This is handy to know in situations where precision is paramount and you don’t want to accidentally move something or, god forbid, delete something from the stage.

Okay, we sort of “stretched the truth” there by telling you that content can’t be added to a locked layer. ActionScript and JavaScript are the only thing that can be added to a locked layer. This explains why many Animate CC designers and developers create an ActionScript-only layer—usually named scripts or actions—and then lock the layer. This prevents anything other than code from being placed in the layer.

The final icon is the Show All Layers As Outlines icon. Click it, and the content on the stage turns into outlines. This is somewhat akin to the wireframe display mode available in many 3D modeling applications. In Animate CC, it can be useful in cases where dozens of objects overlap and you simply want a quick “X-ray view” of how your content is arranged. With animation, in particular, it can be helpful to evaluate the motion of objects without having to consider the distraction of color and shading. Like visibility and locking, the outlines icon is also available on a per-layer basis.

You can change the color used for the outline in a layer by double-clicking the color chip in the layer strip. This will open the Layer Properties dialog box. Double-click the color chip in dialog box to open the Color Picker. Then click a color, and that color will be used.

Grouping Layers

You can also group layers using folders. Here’s how:

Click the Folder icon in the Layers panel. A new unnamed folder—Folder 1—will appear on the timeline. You can rename a folder by double-clicking its name and entering a new name.

Drag the three Butterfly layers into the folder. As each one is placed in the folder, notice how the name indents. This tells you that the layer is in a folder.

Next, remove the layers from the folder. To do so, simply drag the layer above the folder on the timeline. You can also drag it down and to the left to unindent it.

To delete a folder, select it and click the Trash Can icon.

Step away from the mouse and put your hands where we can see them. Don’t think you can simply select a folder and click the Trash Can icon to remove it. Make sure that the folder is empty. If you delete a folder that contains layers, those layers will also be deleted. If this happens to you, Adobe has sent a life raft in your direction. An alert box telling you that you will also be deleting the layers in the folder will appear. If you see that Alert click Cancel instead of OK.

Where To Get Help

In the early days of desktop computing, software was a major purchase, and nothing made you feel more comfortable than the manuals that were tucked into the box. If you had a problem, you opened the manual and searched for the solution. Those days have long passed. This is especially true with Animate CC, because as its complexity has grown, the size of the manuals that need to be packaged with the application also grew. In this version of Animate CC, the user manuals are found in the Help menu. Here’s how to access Help:

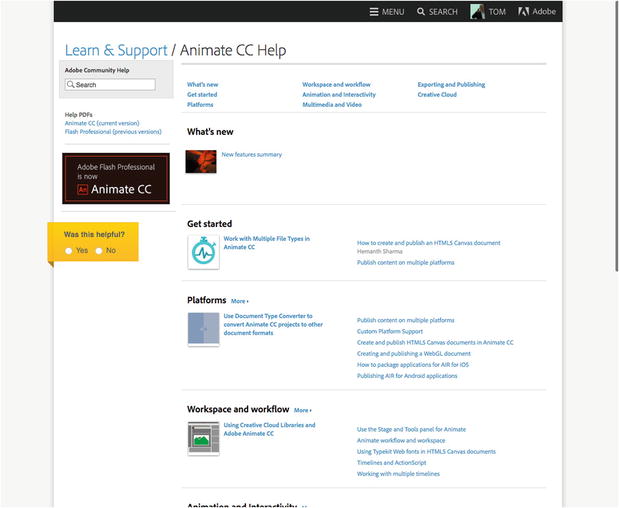

Select Help ➤ Animate Help or press the F1 key. If you are a Mac user, press F1. The Help resource that opens in your browser (see Figure 1-34) is one of the most comprehensive sources of Animate CC knowledge on the planet; best of all, it’s free.

Figure 1-34. The Animate CC Help is extensive

The page is divided into two areas. On the left side you can enter your criteria for very specific topics. Underneath it is a link to a 482-page PDF version of the Animate CC docs, which you can download directly to your computer. The right side of the window allows you to choose a more general topic.

So much for the walkabout. It is time for you to put into practice what you have learned.

Your Turn: Building an Animate CC Movie

In this exercise, you are going to expand on your knowledge so far. We have shown you where many of the interface features can be found and how they can be used, so we are now going to give you the opportunity to see how all of these features combine to create an Animate CC movie.

You will be undertaking such tasks as the following:

Using the Property Inspector to precisely position and resize objects on the stage

Creating layers and adding content from the Library to the layers

Using the drawing tools to create a shape

Creating a simple animation through the use of a tween

Testing an Animate CC movie

Open the MoonOverLakeNanagook.fla file .

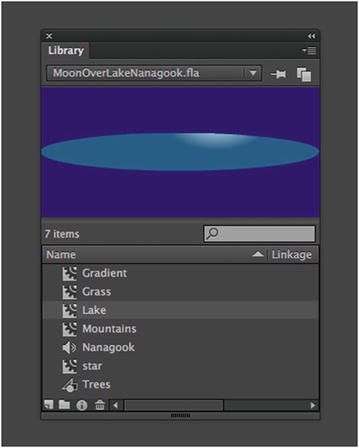

When the file opens, show the Library panel, if it isn’t already in view, by selecting Window ➤ Library or pressing Ctrl+L (Cmd+L). As you can see, you are starting with a blank stage, a few movieclips shown in Figure 1-35, an audio file, and a graphic symbol.

Figure 1-35. The assets are in place. It is your job to turn them into a movie

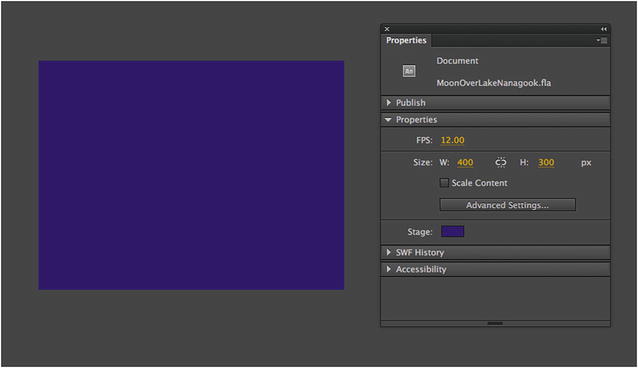

The specifications for the project state the stage is to be 400 pixels wide by 300 pixels high. It also calls for a dark blue stage color to give the illusion of night. Click the Properties tab and change the Width value to 400 and the Height value to 300.

Click the Stage color chip to open the Color Picker . Select the color text and change it from #FFFFFF to #000066 (dark blue). Click OK to accept the changes and close the dialog box. The stage will shrink to its new size and be colored a dark blue. The new size and color will now appear in the Property Inspector , as shown in Figure 1-36.

Figure 1-36. The stage is set

Rename Layer 1 to Gradient by double-clicking the layer name and entering that text. Drag the Gradient movieclip from the Library to the stage.

Though using your eyes for object placement on the stage is a great way to get stuff into position, your eyes aren’t as precise as Animate CC. The gradient needs to completely cover the stage and not hang out on the pasteboard (the non-stage work area) by even one pixel. Here’s how you do that:

Click the gradient on the stage to select it. In the Property Inspector, set its X and Y values to 0. The object will align itself with the upper-left corner of the stage.

Click frame 60 of the Gradient layer and press the F5 key. What this does is add 59 new frames to the timeline; you can tell this because the layer expands to the 60th frame and a rectangle (indicating the new span of frames) is shown at the end of the layer. This gradient is going to be animated later in the exercise.

When Animate CC measures the location of an object on the stage, it uses the upper-left corner of the stage as its 0,0 point. The actual position of the object is based on something called its registration point. In the case of this gradient, the registration point of the symbol also happens to be its own upper-left corner, which is why the X and Y values of 0 cause it to fit neatly on the stage. If the registration point of the gradient were changed to 200,150—that is, down and in from its own upper-left corner—the gradient would end up being positioned partly on the pasteboard and partly on the stage. The symbol’s registration point is indicated by the + sign you see inside the symbol.

Lock the layer by clicking the black dot under the Lock icon on the timeline. This is a good habit to develop. Animate CC projects, including this one, can get fairly complex in a relatively short time. By locking the layer, you are ensuring that you don’t accidentally move the background later on in the project.

Adding the Mountains and Playing with Color

With the stage prepared and the sky in place, you can now turn your attention to adding the assets to the movie. The scene involves mountains, trees, grass, a lake, and the moon. What this tells you is that the objects farthest away need to be placed near the bottom of the layering order. This means that the mountains are the next piece of content to be added.

Add a new layer to the main timeline and name it Mountains.

With the new layer selected, open the Library and drag the Mountains movieclip onto the stage.

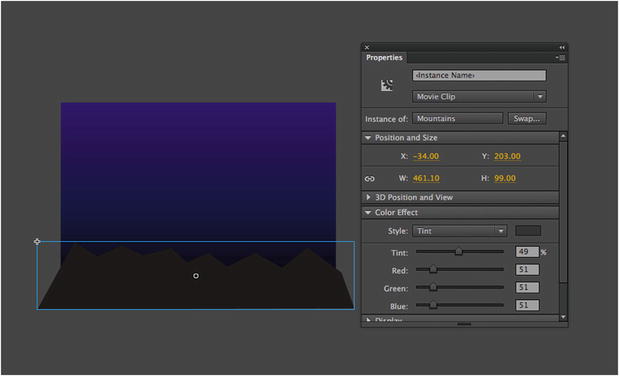

With the mountains selected on the stage, in the Property Inspector, set the X value to -34 and the Y value to 203. The mountain range will sit at the bottom of the stage and hang off of both sides of the stage. There is, of course, one great big problem: the mountains are black and they have been placed against a black background. Let’s fix that.

Select the mountains on the stage and, in the Color Effect area of the Property Inspector, select Tint from the Style drop-down menu. The Property Inspector will change to show you a color chip, a tint percentage, and the RGB color of the selected object.

If you remember what we said earlier, everything on the stage, including the stage itself, has unique properties, including its color. Changing the tint of a selected object allows you to manipulate the color property of that object. The original Library asset’s color is not affected.

Click the color chip, and when the Color Picker opens, select the dark gray color directly under the black chip on the left side of the picker (#333333). The mountains become a lot more distinct, but they are now too obvious.

With the mountains still selected, move the Tint slider until the value is 49% (as shown in Figure 1-37). If you are a power user, feel free to simply double-click the value and enter 50.

Figure 1-37. Objects can have their color properties manipulated

Now is a good time to save your work. Select File ➤ Save As, and when the Save As dialog box opens, navigate to the Exercise folder for this chapter and rename the project. Click OK to close the dialog box.

If you have been using Animate CC for a while, we are willing to bet you missed something rather significant when you added the new layer. Did you happen to catch that the frame span of the new layer matched that of the Gradient layer? In the past, any new layer started off as a single frame and you pressed the F5 key to add a frame to create the span.

Using Trees to Create the Illusion of Depth

The mountains are in place and are faintly visible against the night sky. Let’s add some depth to the scene by adding a couple of trees. Here’s how:

Create two new layers, named Tree1 and Tree2.

Taking turns, drag one copy apiece of the Trees symbol to the stage while each tree layer is selected. This puts each tree on its own layer. You may notice that the icon for the Trees symbol is different from the other symbols in the Library. This icon indicates that the tree is a graphic symbol. Graphic symbols can be created with the various drawing tools in Animate CC—which is the case with this tree—and also make good containers for imported photographs.

Graphic symbols’ timelines are locked in step with the timeline they’re in, unlike movieclip symbols, whose timelines run independently. This explains why graphics are the de facto symbol for JibJab-style animation ( www.jibjab.com/ ). Complex nested symbols can be scrubbed in this way for testing in the timeline, whereas movieclips only show nested animation when published. More on this in Chapters 7 and 8. A symbol placed on the stage is called an instance.

Select the tree on the lower of the two tree layers . Use these values to precisely place the selected tree on the stage, resize it, and darken it:

X: 49

Y: 178.5

W: 65

H: 105

Color Effect: Tint

Tint Color: # 000000 (black)

Tint Amount: 40%

The tree gets smaller, moves to the left side of the stage, and darkens. Resizing the image and darkening it is what gives the illusion of depth in this scene.

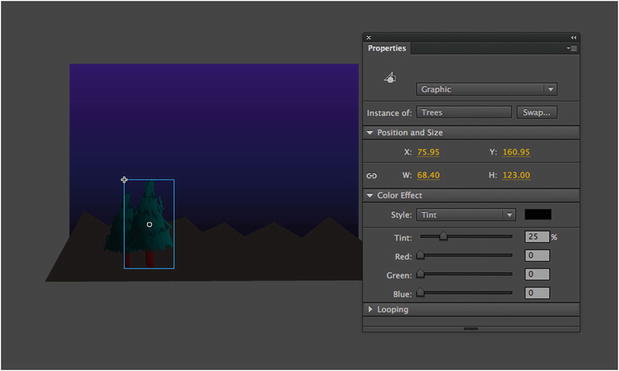

Select the remaining tree and use these values in the Property Inspector :

X: 76

Y: 161

W: 68

H: 123

Color Effect: Tint

Tint Color: # 000000 (black)

Tint Amount: 25%

The tree gets a bit smaller, moves to the left side of the stage, and, due to the low tint amount, becomes a bit brighter than the tree behind it (as shown in Figure 1-38). The reason for this is that it will be lit by the moon, which you will create in a couple of minutes.

Figure 1-38. Location and size are other properties that can be manipulated using the Property Inspector

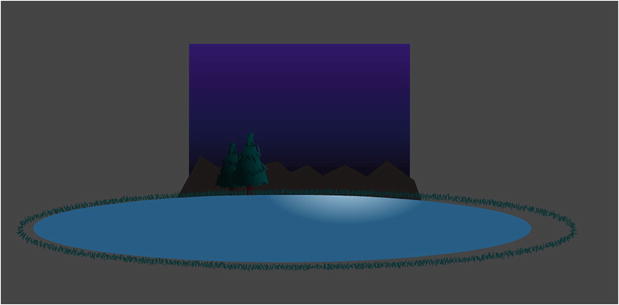

Let’s finish the scene by adding the grass and the lake.

Add a new layer named Grass. With this new layer selected, drag the Grass movieclip from the Library to the stage. Set its X and Y coordinates in the Property Inspector to -306.6 and 268.9, respectively.

What’s with the decimals? This is deliberate. You need to know how to input values as well as scrub the values. You may have noticed that, when you scrub values, the numbers don’t have decimals. If precise placement of objects on the stage is “mission critical,” you need to know how to accomplish this task. But isn’t a decimal value smaller than a pixel? You bet it is, but we’re dealing with vector graphics here.

Add a new layer named Lake. With this new layer selected, drag the Lake movieclip from the Library to the stage. Set its X and Y coordinates in the Property Inspector to -282 and 274, respectively.

So far, so good. It is starting to look like Lake Nanagook (see Figure 1-39), but we need to add two more elements—the moon and a twinkling star—to make it a bit more realistic. We obviously need the moon because it is reflected in the lake, and a twinkling star is a subtle bit of eye candy that will make the scene that much more interesting and catch the viewer’s attention. Let’s start with the star.

Figure 1-39. The project is starting to come together

Using a Motion Tween To Create a Twinkling Star

One of the steady messages running throughout this chapter is that we, as Animate CC designers, are illusionists. In this exercise, you will discover how to create the illusion of a star twinkling in the night sky. Here’s how:

Open the Library and double-click the star movieclip to open it in the Symbol Editor. When the movieclip opens, you will see that it is composed of a layer named diamond. The shape on the stage was created using the Rectangle Primitive tool, making the sides concave and filling the shape with #FFCC00, which is a gold color.

If the shape is too small, select the Magnifying Glass tool on the Tools panel and click and drag it across the star. This is how you can precisely zoom in on an object on the stage.

Right-click on the diamond layer and select Duplicate Layers from the context menu. You now have a new layer named diamond copy. Rename this layer diamond2.

Move the playhead back to frame 1 and double-click the star. This will select the star in the diamond2 layer.

In the Properties panel change its Fill Color, in the Fill & Stroke area, to #FFFF99, which is a faint yellow color.

With the star in the diamond2 layer selected, right-click (Ctrl+click) the star to open its context menu. Select Convert to Symbol and, when the New Symbol dialog box opens, name the symbol star2 and select Movie Clip from the Type drop-down. Click OK to accept the change. You have to convert the rectangle primitive in the diamond2 layer to a symbol in order to apply the sort of tween you’re about to do. Note that converting a symbol from a shape or primitive already in place keeps everything positioned where it was.

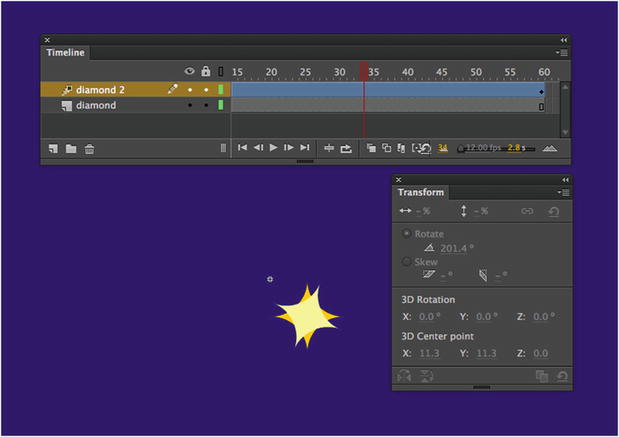

Rotating a Movieclip Using the Transform Panel

The illusion of a twinkling star in the sky is actually quite simple to accomplish. You have to do nothing more than have the star rotate 360 degrees in a clockwise direction, and best of all, it only requires a couple of mouse clicks. Let’s get busy:

Right-click (Ctrl+click) on any frame in the diamond2 layer to open the context menu. When the menu opens, select Create Motion Tween. The span will turn blue.

Select Window ➤ Transform to open the Transform panel or click the Transform panel button in the panels area to open the panel. When it opens you will see you can either Scale or Rotate selected object.

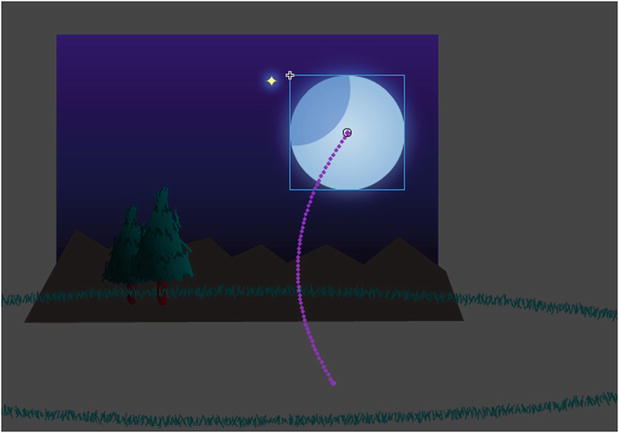

Scrub the playhead to frame 60 and, with the Transform panel open, change the rotate value to 360, as shown in Figure 1-40. Positive values will rotate an object in a clockwise direction whereas negative values will rotate the object in a counter-clockwise direction.

Figure 1-40. Putting a star in motion

Scrub across the frames to see the rotation.

Zoom the stage to the 100% view and click the Scene 1 link on the top left of the stage to return to the main timeline. Save the project.

A Moon Over Lake Nanagook

At this point, we have essentially handed you the assets and let you put them in place and otherwise manipulate them. It is now your turn to go solo and create the moon that rises over Lake Nanagook.

Select Insert ➤ New Symbol. This will open the New Symbol dialog box. Name the symbol Moon and select Movie Clip as its Type. Click OK. The dialog box will close and the Symbol Editor will open.

So far we have used the term movieclip and not put a space between the two words. Why then is the term broken into two words in the dialog box? The use of the single word has developed into a standard throughout the worldwide community when writing about Animate CC. The split word in the dialog box is actually one of the very few references you will see from Adobe using this terminology, which has its roots back in an early release of Animate CC.

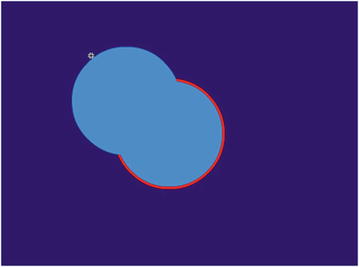

Rename Layer 1 to bg. Add a new layer named shadow. The shadow layer should be above the bg layer.

In the Tools panel, click the Oval tool to select it.

Open the Properties panel and click the Stroke Color rectangle—called a color chip—to open the Color Picker. Set the Stroke color to red. (#FF0000). Click the Fill color chip and select a light blue. While you’re there, give the Stroke a value of 3 to help it show up better.

Select the first frame of the bg layer and, with the Oval tool selected, click the stage and drag out a circle. Switch to the Selection tool and double-click the circle to select both the fill and the stroke. In the Property Inspector, change the circle’s width and height values both to 120, making a perfect circle, and set the X and Y coordinates to 0. This is your moon—or the beginnings of it.

With the moon still selected—again, you’ve selected both the stroke and the fill—copy it to the clipboard.

Select the first frame in the shadow layer and paste the shape from the clipboard into this layer.

With the newly pasted shape still selected, move it upward and to the left, so that it overlaps the bottom layer, but both circles show. These shapes should look something like what you see in the movies when a character looks through binoculars.

Click the Show All Layers as Outlines button to temporarily display both circles as outlines. The intersection between the two shapes should look like football or rugby ball. Click the Show All Layers as Outlines button again to exit the outlines mode. Click the red stroke on the shape in the shadow layer to select it. Press the Delete key to remove it. You now have a solid blue circle over another circle that has a red stroke (as shown in Figure 1-41).

Figure 1-41. The moon shadow starts out as a couple of circles

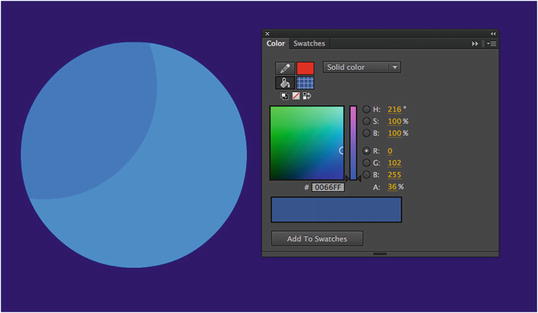

Select the red stroke around the circle in the bg layer and cut it to the clipboard. Select the shadow layer and select Edit ➤ Paste in Place.

What has happened here is that the stroke you just pasted into the shadow layer has actually cut the football shape for you. The reason this is possible is because you turned off Object Drawing mode in the Properties panel.

In the shadow layer, click the portion of the blue circle that is outside of the stroke. Press the Delete key. Now select and delete the stroke itself. If you turn off the visibility of the bg layer, you will see that you have created the shadow shape. Let’s make it a true shadow.

Click the football shape to select it and then open the Color panel by selecting Window ➤ Color.

Set the fill color to #0066FF and reduce the alpha value to 36%. Turn on the visibility of the bg layer. You will see that you indeed have a shadow (as shown in Figure 1-42).

Figure 1-42. The shadow is created by using the Color panel

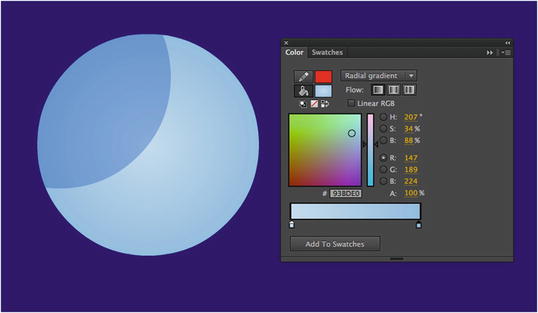

The final step in the process of creating the moon is to add a gradient fill in order to give the moon a bit of a glow. Follow these steps:

Select the circle in the bg layer and open the Color panel.

Select Radial gradient from the Type drop-down. The moon turns into a black-and-white radial gradient. The gradient colors are shown in the strip—called a “ramp”—and there are two color stops under the ramp indicating the colors used. These stops are called crayons.

Click the black crayon to select it. Change the hex color under the Color Picker to #C4DDEE.

Click the white crayon and change its color to #93BDE0. The moon takes on a faint glow, thanks to the similar colors in the gradient (see Figure 1-43).

Figure 1-43. Add a radial gradient through the Color panel

Click the Scene 1 link to return to the main timeline.

Add a layer named Star and another named Moon. These layers should appear above the others.

Add the star symbol to the Star layer and set its X and Y coordinates to 219 and 42, respectively.

Add the moon symbol to the Moon layer and set its X and Y coordinates to 241 and 43, respectively.

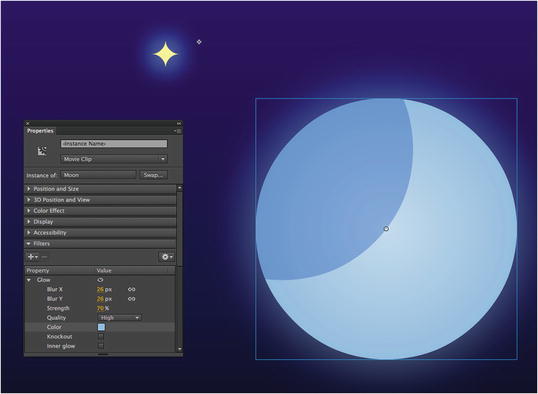

Next, let’s really make the moon and the star glow in the sky over Lake Nanagook. Let’s add a glow effect to both of them. Here’s how:

Select the star on the stage and click the Filters twirlie on the Property Inspector to open the Filters area.

Click the + sign to see the Filters list. Select the Glow filter.

Use these settings in the Glow filter:

Blur X: 14

Blur Y: 14

Strength: 418%

Quality: High

Color: #93BDE0

The star looks like it is about to go into supernova. Let’s make it a bit smaller.

With the star selected on the stage , set its width and height values in the Property Inspector to 13.

Select the moon on the stage and apply the following Glow values:

Blur X: 26

Blur Y: 26

Strength: 70%

Quality: High

Color: #93BDE0

The moon and the star in Figure 1-44 now look like they belong together in the sky.

Figure 1-44. Adding a filter to a movieclip

Filters can only be added to movieclips, text fields, and buttons.

Save the project.

Breaking the Stillness of the Night at Lake Nanagook

If we are going to have an outdoor scene, it only makes sense to add some outdoor sounds to the mix. Fortunately, adding audio to an Animate CC file is not terribly complicated.

Add a new layer and name it Audio.

Open the Library and locate the Nanagook audio file.

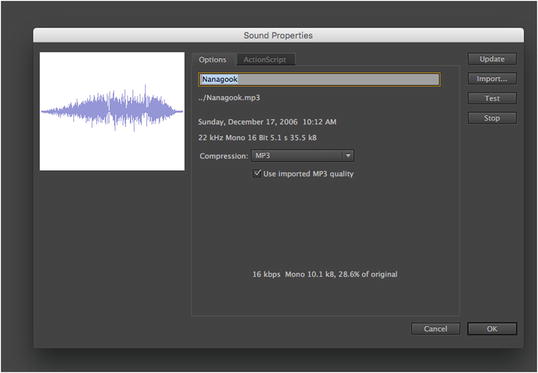

Double-click the sound file in the Library to open the Sound Properties dialog box. Click the Advanced button (shown in Figure 1-45) to reveal all of the features of this panel.

Figure 1-45. Preview sounds in Animate CC by clicking the Test button

Click the Test button to preview the audio file. Ahh, the sounds of crickets and wolves howling in the night. Click OK to close the dialog box.

With the Audio layer selected, drag the sound file from the Library onto the stage. When you release the mouse, the audio waveform appears in the layer.

Dragging a sound file from the Library to the stage isn’t the only way to get an audio file to the timeline. In many respects, what we’ve shown is not exactly regarded as a best practice because audio files can be big, and when they are in the Library, they can seriously increase the file size and take an inordinate amount of time to load if viewed online. We have a whole chapter, Chapter 5, devoted to audio best practice, so for now, let’s content ourselves with getting sound into the presentation and getting it to play.

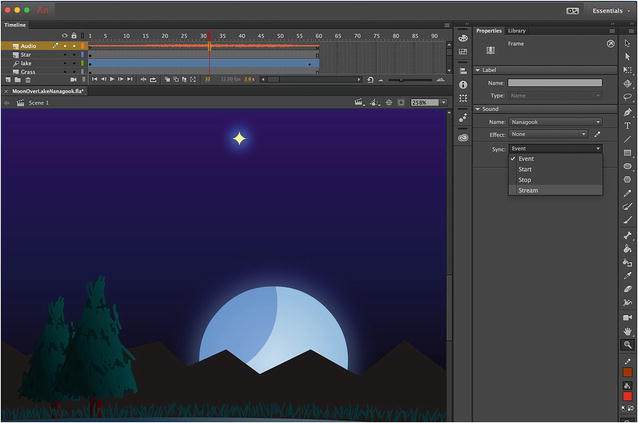

Click anywhere on the sound’s waveform in the Audio layer, and you will see the Property Inspector change to show the sound properties (open the Sound twirlie, if you need to).

Click the Sync pop down and select Stream from the menu (as shown in Figure 1-48).

Scrub across the timeline and you will hear the audio file. This is possible because of the Sync change you made in Step 7. Drag the playback head to frame 1 and press the Return (Enter) key. The sound will start playing, but it abruptly ends at frame 50. This is because the audio was originally recorded for a slower movie frame rate.

Scroll the timeline so you can see frame 130. Click into the Audio layer at frame 130 and drag downward without lifting the mouse—until you hit the Gradient layer. This selects the last frame of all your layers. Press the F5 key. This adds enough frames to every layer so that the sound has enough room to play completely.

Save the file.

Picking up a pattern here? Get into the habit of saving the file every time you do something major to your movie. This way, if the computer crashes, you won’t have a lot of extra work in front of you trying to reconstruct the movie up to the point of the crash.

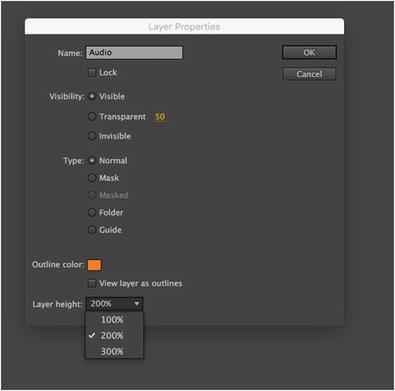

You may have looked at Figure 1-46 and thought, “Hey my audio layer doesn’t look like yours.” Good eye. Layers can also be made larger. To do this, right-click (Ctrl+click) on a layer’s name to open the context menu. Select Properties to open the Layer Properties dialog box shown in Figure 1-47. Select 200% in the Layer height drop-down list or enter your own value. Click OK to accept the change.

Figure 1-46. Audio on the timeline, and the sound properties in the Property Inspector

Figure 1-47. Even layers have their own properties

Testing Your Movie

You have created the animation and scrubbed through the timeline, and everything looks like it is in order. Now is a good time to test your movie in Flash Player. We can’t understate the importance of this step in your workflow. The procedure, as one of the authors is fond of telling his students, “Do a bit. Test it. Do a bit more. Test it.” The reason for this is that Animate CC movies can be quite complex. Each element you add to your movie adds to the complexity of the movie. Developing the habit of regularly testing your work, regardless of how simple it may be, will point out mistakes, errors, or problems in the work that you’ve just completed.

What it comes down to is this: do you really want to burrow through a complex movie, and even more complex code, searching for an issue, or do you want to catch it early? Here’s how to test an Animate CC movie:

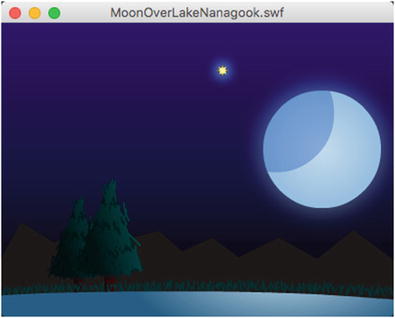

Press Ctrl+Enter (Cmd+Return). You will see an alert box telling you that the movie is being exported, and the movie will open in Flash Player (as shown in Figure 1-48). What you should see is the star twinkling in the sky—and all of the stuff outside the boundaries of the stage has been trimmed off.

Figure 1-48. Testing a movie in Animate CC Player

If you insist on using a menu, select Control ➤ Test Movie ➤ In Animate.

If you open the folder where you saved the FLA file, you will see that a SWF file has also been added to the folder.

Moonrise Over Lake Nanagook

We’ve been gently reminding you that Animate CC involves the art of illusion. The other thing you need to know is that Animate CC developers are fanatics about detail. They pay close attention to their environment and then try and mimic it in their projects.

In this final piece of this exercise, we are going to get you up close and personal with that last statement. The plan is to have the moon rise into the night sky. On the surface, that sounds like a no-brainer: tween the motion of the moon between its start position and its finish position. Not quite.

This is a night scene, and if there is no moon, things are quite dark. They only light up when the moon is in the sky. If you look at Lake Nanagook, you can see there is a problem. The lake already contains the reflection of the moon. The lake should be dark and only start to light up as the moon rises in the sky. The other issue is the trees. They, too, are lit by the moon and they should be dark and start to light up as the moon rises.

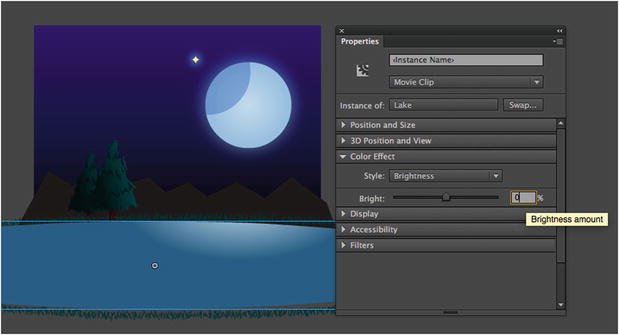

Although this may all sound rather complex, it can all be handled by the Property Inspector. Follow these steps to start yourself on the path to becoming a fanatic about detail: