4

The Right Way to Write It

What You’ll Learn_________________

Now we’re getting away from the mechanics of writing a broadcast news story and into the idiosyncrasies. What does it mean when you’re told that someone is in “fair condition” at the hospital, as opposed to “serious condition”? When do you attribute facts to someone else and when do you simply present them without attribution? How can you possibly count all the people participating in a huge public demonstration?

This chapter is sort of a “catch-all” for lessons that didn’t logically fit into the chapters before it. It’s about the kinds of things that can jeopardize your credibility, not to mention your respect, if you get them wrong. Unlike simple rules such as “don’t abbreviate” and “don’t use symbols,” these aren’t the kind you can memorize. No, these are the kind whose meaning and purpose you must learn, and almost make a part of you. They are about things that will come up often in your career as a journalist.

Eventually they will be second nature to you. Now though, just read them, think about them, and practice them in whatever you write. Your credibility, and your station’s, are at stake.

Before you get started, look back to your own improved version of the “Never Ending Story.” Here are the corrections you should have made:

In a place where a rear-ender traffic accident’s accident is usually the biggest event of the day, there’s there has been an event with an impact on everyone. Tonight the lives of three people have been claimed by a bomb, which set off a 3-alarm three-alarm fire that raised temperatures to almost 200° 200-degrees Fahrenheit at a clothing store at 3645 Main Street, in the heart of Ft. Fort Stutter, Calif., California, the police say. No group has taken credit for the blast, but forensics experts 0tonight are combing the scene of the attack. tonight and in In case there’s there is more danger there, a hazardous material team’s team is dispatched to the scene. They’re driving three separate emergency vehicles to get there. In order to To explain why there wasn’t was not a warning, the police chief of the city of Ft. Fort Stutter, Jazibeauz Perez (JAZZ-uh-boo PEAR-ehz), says there was definitely no sign that the bomb was going to explode, then he said, “Everyone wishes to God we’d known this was going to

transpire.” The police dept. department hasn’t asked the FBI F-B-I for help, the chief says. The dead includes include Jason J. Jones, 29, Sally S. Smyth (Smith), 24, and Greg G. Goldstein (GOLD-steen), who died at 22. None were employees at the bombed store. Two unidentified men are in critical condition, meaning they might die too. Everyone in Ft. Fort Stutter is scared now to go out on the street, and city officials say increased protection will cost the people of Ft. Fort Stutter a lot of money, $6-million more than six million dollars. There isn’t a is no date set for a decision about spending that amount of money, but the mayor can’t cannot be back in town by Tues. Tuesday, which isn’t is not early enough for her critics. Whether it’ll it really will really be helpful remains to be seen.

At the end of this chapter, you’ll have another shot at fixing problems that won’t seem like problems until you finish the chapter.

Leaving Expert Judgment to Others

We’ve all read it, or heard it: “The patient is in critical condition.” Or “poor condition.” Or whatever. When someone is taken to the hospital, whether due to a crime, an accident or an illness, you may be assigned to cover it because of the person’s prominence or because of whatever got him there. You may have to write or speak these very words: “The patient is in ______ condition.”

In rare circumstances you might be able to stay with the patient and hear what the doctors are saying about his condition. But usually you won’t. Usually you’ll have to depend on a spokesperson, someone whose job is to speak for the hospital, or for the patient (typical with entertainment, sports, and political celebrities).

What you’ll probably be told is this: the patient is in critical, unstable, serious, poor, stable, fair, good, or excellent condition. Huh? What does “critical” mean versus “serious”? What’s the difference between “stable” and “fair”?

Guess what: you don’t have to know. This is one of those atypical cases—one of those “exceptions” to the rule of understanding everything you write—where you don’t have to understand the patient’s condition, you only have to describe it as it has been described to you. It’s up to the doctors, or other medical experts there, to understand it and, through you, to convey it to your audience.

Why? Not because you can’t possibly understand the difference between “stable” and “fair,” but because you can’t possibly know which one describes the person you’ve been sent to cover. You have to rely on what the spokesperson tells you.

Having said that, let me give you a rough idea what each of those terms means. To begin with, a couple of paragraphs earlier, I listed them roughly in order of their import from the worst to the best: critical, unstable, serious, poor, stable, fair, good, and excellent.

Now, only for your guidance, let me specifically define them. But bear two things in mind: the medical staff provides the “level of care” and you just report it without interpretation, and some of these terms are synonymous with, and only can be defined in relation to, others.

| Critical | The patient is hovering between life and death. |

| Unstable | The patient is critical but if his or her vital signs can be stabilized, the condition will be upgraded to serious. |

| Serious | The patient has a life-challenging problem, but as long as medical staff can maintain the stability of the patient’s vital signs, doctors do not expect the problem to be fatal. |

| Poor | The patient is very sick but his life is not threatened. |

| Stable | The patient’s vital signs are under control and doctors have reason to believe they will be able to upgrade his condition to fair. |

| Fair | The patient can perform some functions for himself and is showing no indications of slipping into a worse condition. |

| Good | The patient is one step from the hospital’s exit, and probably only needs additional resting or strength-building time before release. |

| Excellent | The patient is being observed but is showing no ill effects. |

What’s the Point?

As a journalist you should question everything. But in a handful of circumstances, you have to uncritically accept and apply the answer. One such case is attributing “responsibility” to terrorists for their acts, not “credit.” Another is reporting a patient’s condition just as it is reported to you, without embellishment, without elaboration.

Giving Credit Only Where Credit Is Due

Here’s a lesson a lot of veteran journalists never have learned: if we don’t want to glorify terrorists, we shouldn’t write about them taking “credit” for their acts. Taking “credit” for something has a positive connotation. For instance, here’s a defective headline from the Rocky Mountain News in Denver after a book was published about Oklahoma City federal building bomber Timothy McVeigh: “McVeigh takes lion’s share of credit for bombing Murrah federal building.” Or, in the spirit of equal time, here’s an equally irresponsible headline from a story in the News’s competitor, The Denver Post, after a radical environmental group said it had set some buildings afire at the Vail ski resort: “Earth Liberation Front takes credit.”

No! By definition, terrorists do not deserve “credit.” So whether you write newspaper headlines or broadcast scripts, remember this: terrorists themselves may consider the word “credit” to be credible, but if journalists buy into the word themselves, they provide an unintended but apparent endorsement of the act. Instead, terrorists “take responsibility.” Or if someone says they did it but we cannot be sure (a lot of fanatics and just plain nut cases will say they did something terrible even if they didn’t), we write that they “claim responsibility” for the terrorist action. Although in other contexts the word “responsibility” has a positive connotation (as “credit” does), in this context it merely means, “the people responsible.” The lesson is, you don’t want to attach a positive connotation to a negative act.

So when do you give credit? That brings me to attribution.

You Don’t Always Have to Attribute Things

There are theories, and there are facts. There are accusations, and there are facts. There are assumptions, and there are facts. In each case, you as a journalist must distinguish between them. One way to do so is with “attribution.”

What is attribution? It is the act of giving somebody credit or blame for something. It is the act of making it clear to your audience that you’re merely reporting what somebody else has told you, rather than reporting something that you yourself have seen or irrefutably deduced. Here’s a simple example of attribution:

The police spokeswoman says the ex-Marine was drunk when he pointed a gun at the bank teller, then during his getaway was injured in a four-car crash.

The writer has “attributed” the description of the ex-Marine—that he was “drunk”—to the police spokeswoman. Why is it important to attribute the description? Because it might not be true. Maybe the ex-Marine was high on drugs rather than alcohol. Maybe he was afflicted with an illness that misleadingly gave him the appearance of drunkenness. Maybe the blood alcohol level in his blood was high but not high enough to qualify legally as “drunk.” By attributing the “drunk” description to the police spokeswoman, you’re making it clear that it is her description, not yours. Furthermore, you’re partially protecting yourself (more in Chapter 20 under Libel) if eventually the ex-Marine proves that it’s not true. And, you’re being fair. A fair story attributes claims, charges and characterizations to their sources. So in the simplest sense, that’s attribution, with a pretty good example of when it’s necessary. But how necessary is attribution in this simpler example?

The police spokeswoman says the ex-Marine pointed a gun at the bank teller, then during his getaway was injured in a four-car crash.

Well, while the bank teller herself probably will testify in court that the ex-Marine pointed a gun at her, the ex-Marine might testify that he was pointing it at the ceiling or at the floor. His lawyer then could make the case that the ex-Marine meant no harm to the teller, which could result in a lesser conviction or a lesser sentence. Or the ex-Marine might testify that he only had his hand in his pocket, but no gun. The point is, one of your responsibilities as a journalist is to avoid prejudicing a case. One safe way is to attribute things to your sources, rather than to state them yourself as facts. But attribution can go overboard too. Would you need attribution for the following?

The police spokeswoman says the ex-Marine was injured in a four-car crash.

No, definitely not. If his injury in the crash is a fact, uncontroversial and indisputable, it can be stated as a fact, without attribution. Like this:

The ex-Marine was injured in a four-car crash.

Likewise, if you get a call from the police telling you that there is a bad accident blocking Main Street during the downtown rush hour, and you want to inform your audience right away, you don’t have to write it this way:

Police say there is a bad accident blocking Main Street.

Why not? Because the accident is neither a theory, an accusation, or an assumption. It is a fact. Main Street is blocked. An accident caused it. Just say so, without attribution:

There is a bad accident blocking Main Street.

What’s the Point?

If you don’t know that it’s true, attribute it. If you do know, or don’t know firsthand but have absolutely no reason to doubt it, don’t bother with attribution. It’s unnecessary.

Print Journalists Don’t Write the Way They Talk

How many times have you seen a sentence that ends like this in a newspaper or a magazine?

The suspect released his hostages and surrendered, police say.

Conceivably this is a story that is unfolding beyond your view, so you have to depend on police accounts of the event. Therefore the question here isn’t about attribution. It’s about writing the way you talk.

You probably wouldn’t sit at the dinner table and tell your tablemates, “It’s supposed to rain tomorrow, the weatherman says.” Or you wouldn’t say, “A helicopter crashed this afternoon at O’Hare Airport, Channel 4 reports.” That’s because you don’t talk that way. No, you’d probably say:

I heard on Channel 4 that a helicopter crashed this afternoon at O’Hare.

What you want for a broadcast news story is that same sentence, modified to fulfill the needs of the newscast:

Channel 4 is reporting that a helicopter crashed this afternoon at O’Hare Airport.

Or in the case of the weather:

The weatherman says it’s supposed to rain tomorrow.

Yet many broadcast writing students write news stories the way they’ve seen them written in newspapers and magazines, which I call “print style.”

If you write like this because you’ve seen so much of this, then the lesson here is simple. Forget what you have seen. Print is a different medium with a different style than broadcasting. So if you’re writing about the suspect releasing his hostages, write it this way:

Police say the suspect released his hostages and surrendered.

What’s the Point?

I’ll make this point as often as I can. Don’t write the way you read; write the way you talk.

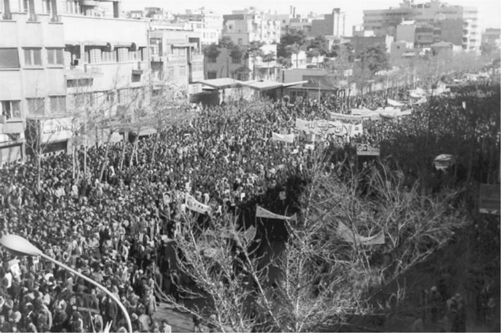

Crowds, Dead or Alive

The biggest crowd I ever saw was in Iran, during a revolution that ultimately overthrew the pro-Western leader, known as the Shah, and replaced him with a radical Islamic leader, known as Ayatollah Khomeini. The crowd was impossible for me to count. They were marching down the main street of the capital, Tehran, from a point beyond my field of view and to a point also beyond my view. What’s more, the boulevard along which they marched was packed to the horizon, and wide enough to rival the widest avenues in the world.

So what could I do? In the chaos of the revolution, and since it was a third world country, no one reliable was offering any official estimates—and as you’ll read in a moment, “official” estimates sometimes are the least reliable of all. (Actually, since an estimate is supposed to rely at least on evidence, occasionally what officials call an “estimate” actually is no more than a guess, which means mere conjecture, and sometimes that guess is shaped by the officials’ political agenda.) Renting a helicopter to see everything from the air—which you might do in an American city—wouldn’t work; airspace was closed to everything but military aircraft. Guesswork was out; you shouldn’t guess at a crowd’s size any more than you should guess at anything else.

Yet to reflect the volume of popular sentiment for the revolution, I wanted somehow to convey the enormity of the demonstration. I knew from experience estimating other crowds elsewhere that this was huge. I felt pretty sure that I could have said “half a million” and not been too high. But if I wasn’t sure, I couldn’t say it. Furthermore, if the crowd was twice that size, then “half a million” didn’t come close to telling the story.

But I wasn’t out of tools. Although I knew where the march started and where it ended and therefore knew how much I could not see, I also knew from the balcony where I stood what I could see. And that’s what I worked with. How? By visually (actually, using my thumb and forefinger) cutting the crowd into segments. First I took in the whole scene in my field of view, which was maybe two miles long, and found the approximate halfway point. Then, by isolating just half my field of view (with my thumb and forefinger), I knew I was looking at about fifty percent of the crowd that I could see.

Then I did the same thing again with that segment: I found its approximate halfway point and split it in half again. Now I had isolated just twenty-five percent of the crowd (that I could see). Then I didn’t just split that part in half; I split it into fifths, so that my thumb and forefinger only framed about five percent of the visible part of the demonstration.

Sometimes that’s small enough to make a roughly accurate count. If so, count the heads in the area you’ve segmented, and multiply by twenty (20 × 5% of a crowd = 100% of the crowd). If it’s still not small enough, then split that segment into fifths again, so that essentially, you’re isolating only about one percent of the crowd. Make your count, then multiply by one hundred (to come up with 100% of the crowd).

In the case of this colossal crowd in Tehran, I had to split my visual segments into even smaller parts, which became just fractions of one percent. But the process was the same, and I came up with a very rough figure of about 1.5 million people that I could see. Knowing the length of the route that was beyond my field of view both east and west, I could confidently write the following line, “Today’s march, like others, stretches too many miles to be measured by the naked eye; millions is a fair estimate.”

It’s a lot of work for a single sentence in a story, but that’s what journalism is about. Anyway, this was for television, so the pictures added a dimension that I didn’t have to waste more words to describe.

Most of the time, you won’t have millions to count. But you will have thousands, sometimes tens or hundreds of thousands. The trick is to find a high point—a window, a balcony, a hill, a rooftop, if not a helicopter—then use your fingers and do the math!

You may recall my admonition about “official” estimates. Here’s what I mean. There was a big demonstration in Denver by people protesting gun control. The National Rifle Association, which supported the demonstration and arguably had an interest in inflating the figure, announced that more than twenty-five thousand gun rights supporters had taken part. The Denver Police Department, whose leaders favored gun control and therefore opposed the demonstration, arguably had an interest in deflating the figure and, sure enough, announced that the crowd didn’t amount to more than ten thousand.

Who was right? By my own estimate from a window overlooking Civic Center Plaza where the protest took place, neither side. In fact, my independent and probably more scientific estimate came up with a figure close to halfway between the two advocates, about eighteen thousand. So that’s what I said in my report. The two interested parties had hoped for a crowd the size they announced. I had counted and then made a more accurate estimate.

In a different kind of story, the other thing you need to know about counting people is that when there’s a disaster like a hurricane or a plane crash, the count might keep changing. Maybe searchers find more bodies and the death toll rises. Maybe authorities discover the same name duplicated on two different lists and the death toll drops. That’s part of the reason why the final official death toll from the terrorist attacks on September 11, 2001 ultimately was only about half the original estimates. This kind of thing happens all the time. The question is, how do you handle it? By letting your audience know. You’d like to give a precise number but you can’t, so you make it clear that the number might change. Here are a few hypothetical examples.

A plane carrying ninety people has crashed and burned in a forest outside your city. The first body count to reach you is twenty-five, but common sense tells you that as more rescuers reach the scene, the count is likely to rise. So you write something like this:

At least 25 people have been killed in a plane crash.

Then, if it turns out that the rest of the people miraculously survived, you haven’t misreported anything. But if the death toll does go up, you can clearly revise your next report:

80 bodies now have been found.

Give or take a body or two, official death tolls in plane crashes usually rise rather than fall as more reports come in.

The famed radio commentator Paul Harvey, dealing with the breaking news of a Chinese jetliner crashing into a mountain in South Korea when casualty counts still were fluc-tuating—in retrospect, one hundred-eighteen were killed but remarkably, thirty-nine survived—wrote it this way: “Some survived, most did not.”

But how about natural disasters, where the devastation is generally more geographically widespread and where more agencies, not to mention civilians, are involved in search and rescue operations? It’s not uncommon for initial death toll reports to be done this way:

200,000 people are dead in an earthquake in Turkey.

Typically this kind of round figure comes from a government official’s initial impression, based on how many towns have reported devastation, combined with estimates of deaths from a few. But those estimates are almost never accurate, because they include people buried in rubble. It usually takes days—even weeks—for everyone to be dug out, and for survivors to report friends and family who are missing. So rather than writing a sentence like the one above, instead write a sentence which makes it clear that the death toll isn’t yet official:

200,000 people are reported dead in an earthquake in Turkey.

Or:

Officials estimate that 200,000 people are dead in an earthquake in Turkey.

Here’s How It Really Works

Let me give you real examples from three consecutive stories after an earthquake in one of the poorest countries on earth. It had toppled village after village in the central mountains of Yemen. Homes, primitively built of mud baked hard in the sun, collapsed on top of their occupants. Most of the dead were women, because in that part of the world, men socialize in the open air while women rarely stray from home. The proportion of women killed was especially high in this earthquake because it started just as they were home preparing the day’s major meal. Sadder still, when the earthquake struck, many children were inside with their mothers.

It was impossible for anyone—foreign journalists, local journalists, government offi-cials—to know how many people had been killed. It’s probably fair to say that no one ever quite knew how many people inhabited these villages even before the earthquake.

Yet we had to try to characterize the scale of the earthquake’s impact. Pictures helped, of course. From a Yemeni Army rescue helicopter on which we hitched a ride, we were able to shoot enough aerials—shots from the air—that any viewer would know that a lot of people must have died. It was obvious. But how many? Here’s how we handled that question in the scripts.

• Story #1:

They’re not only finding more bodies here this morning—the official death toll continues to rise well beyond a thousand—but they’re even finding more villages that were devastated by the earthquake and its three sharp aftershocks.

• Story #2:

On the ground here today, searchers found still more bodies. The official death toll is past twelve hundred now, and enough people still are missing that authorities expect it to surpass two thousand.

• Story #3:

(This one dealt with one particular village. Without giving a number I could not yet support, I still conveyed the scope of the tragedy there.)

This village had about 600 inhabitants. About a quarter already have been dug out, and buried in these impromptu graves …”

One unforgettable example of the difficulty of coming up with good numbers hit Americans painfully close to home: those attacks on September 11, 2001. Terrorists hijacked four commercial airplanes, crashing two of them into the twin towers of New York’s World Trade Center, another one into the Pentagon near Washington D.C., and the fourth— probably meant to destroy either the White House or the U.S. Capitol—into a field in Pennsylvania.

Officials from the two airlines whose planes were hijacked, American and United, knew precisely how many passengers and how many crew members died. But the military took days to figure out who was working in the part of the Pentagon that was hit, and who survived. What’s more, there was no central clearinghouse for information from the World Trade Center in New York. Hundreds of companies had their offices and stores there. How many people had come to work? How many were out of town? How many visitors were in the building? How many delivery people? How many were eating in the spectacular restaurant at the top?

Nobody knew. Most of the corpses were burned or pulverized by the collapse of the skyscrapers. That’s why the total death toll from the terrorist attacks wavered from week to week. At one point just a few days after September 11, it was put as high as twenty thousand. Once authorities started compiling lists, it dropped to about seven thousand. Eventually it was officially established below four thousand. But nobody knew for sure. In fact some news organizations, collating information from New York City’s Medical Examiner, funeral homes, places of worship, courts and public agencies, death notices, employers, and families came up with figures even lower. Journalists had to qualify the number every time they reported it. It was “The latest death toll” or “The newest official death toll” or something similar.

Another story, just half a year later, also illustrates the need to qualify your numbers. Do you remember the commercial crematorium (or crematory, both words are correct) in Georgia where the owner wasn’t bothering to burn the bodies entrusted to him? He said his oven was broken and he was having trouble getting it fixed. Instead of cremating the remains, he was stacking them in piles, stuffing them in sheds, dumping them in the woods, burying them helter skelter, and otherwise inappropriately and illegally disposing of his customers’ beloved remains.

Originally, a few bones were discovered on the grounds of the crematorium. That led authorities on the chase. First they found more than a dozen bodies, then the number jumped to more than a hundred, then they added the grounds of the owner’s nearby home to their search and the number reached almost two hundred, then just over two hundred, then close to three hundred and eventually well over three hundred—all in the space of about a week.

As a journalist, you could report the hard numbers, the death toll “to date.” But it became obvious pretty fast that it would keep rising. So if at a certain point you only wrote something like, “Authorities have found one hundred eighty-six sets of human remains,” it would be incomplete because it would sound complete! There are many ways to qualify it. Here are a few:

Authorities have found 186 sets of human remains, and they continue to search.

Authorities have found 186 sets of human remains, and they expect to find more.

Authorities have found 186 sets of human remains so far.

You might even tell why they don’t think the number will stop at one hundred eighty-six:

Authorities have found 186 sets of human remains, but after consulting with local funeral parlors about the number of corpses sent in recent years to the crematorium, they expect to find more.

What’s the Point?

Whether you’re reporting how many people marched in a protest or died in a plane crash, the principle is the same: find out as specifically as you can, and if you can’t, it’s better to say you don’t know than to say you know when you don’t. Additionally, when the number might change, make it clear to your audience.

Personalizing Complex Economics

A different kind of problem comes up with a different kind of number. An economic number.

Let’s say you’re writing a story about the latest national unemployment figures. The federal government’s summary might just say something like, “Unemployment figures dropped this month to 4.5%.” Is that good or bad? And relative to what? Your audience needs some kind of comparison to put the statistic into perspective. So when you write your story, compare it to one of two different figures: either last month’s unemployment rate or the unemployment rate the same month last year:

Unemployment figures dropped this month to four-point-five percent, down from four-point-seven percent last month.

Or:

Unemployment figures dropped this month to four-point-five percent, which is still worse than the four-point-two percent unemployment rate at this time a year ago.

There’s another way to present it too. Personalize it. Perhaps you still want to provide a comparison like the ones in the examples above. You can, and it’s even better to add a context to which everyone can relate. For example:

Unemployment figures dropped this month to four-point-five percent. This is better than last month’s four-point-seven percent rate, but it still means almost five million Americans are out of work.

Or:

Unemployment figures dropped this month to four-point-five percent. This is better than last month’s four-point-seven percent rate, but it still means one out of every 22 Americans is out of work.

An even drier kind of economic story you might have to write is the latest report on the Gross Domestic Product (GDP), which means the value of goods and services produced in the United States. It’s a key figure on which many important economic projections are based. But for your audience, it’s a figure in the trillions of dollars, almost impossible to comprehend. So you aren’t really helping anyone understand it if you simply report, “The Gross Domestic Product has reached eleven-trillion dollars.”

How can you personalize it? A couple of examples, which you can create by doing a bit of simple long division (dividing 11,000,000,000,000 by the United States population, which you can learn in an almanac is approaching 300,000,000 people. If you ask about the population on the search engine known as Ask Jeeves [www.ask.com], you’ll learn that by the year 2050, the population of the United States is expected to reach 400 million.).

The Gross Domestic Product has reached eleven-trillion dollars. This comes to about 39-thousand dollars for every man, woman and child in the country.

Or:

The Gross Domestic Product reported by the Government today comes to about 39-thousand dollars for every man, woman and child in the country—a total of eleventrillion dollars.

Notice, by the way, that I write that it comes to “about 39-thousand dollars.” Why? Because most people, except a few fastidious accountants, don’t need the precise figure down to the penny. Keep it simple. The rough per capita figure for the GDP—$39,000—is all your audience needs.

Of course if you work for a program that specializes in economic news, you may want to be more precise. This is particularly true when reporting stock market figures. If you’re with a general interest news organization and the Dow Jones Industrial Average has gone up 49.2 points, you might want to simplify it by rounding it off, writing: The Dow Jones Industrial Average went up today almost 50 points.

On the other hand, if you report to an audience that wants more specifics, give ’em more!

When President George W. Bush presented his first federal budget to Congress, it was for more than $2 trillion. The number is just too huge to comprehend. So a writer for the Knight Ridder News Service decided to do a little feature putting “trillion” into perspective. Here are a few of the pictures he conjured up:

“You have not lived a trillion seconds. The country has not existed for a trillion seconds. Western civilization has not been around for a trillion seconds. One trillion seconds ago—31,688 years—Neanderthals stalked the plains of Europe.”

“President Bush’s budget request is for $2.128 trillion. Stacked in dollar bills, the pile would stretch nearly 144,419 miles. That’s two-thirds of the distance to the moon, more than five laps around the Earth at the equator.”

He helped us understand just how huge a trillion really is. Only half tongue-in-cheek, he also went on to write of government bureaucrats, “Not only can they comprehend it, they can spend it.”

What’s the Point?

The whole purpose of your job as a news writer is to convey information in a way the audience can understand. When working with big numbers it’s especially important. Keep a calculator handy.

Take My Word for It

A hypothetical situation: you’re in the newsroom when you hear that a bomb threat has been phoned into the local Wal–Mart. The store is being evacuated. One reporter immediately is dispatched to the store to cover the story firsthand; you’re assigned to collect as much information as you can on the telephone.

Your first call? Wal–Mart, of course. And it’s your lucky day, because the clerk who answers the phone is the one who took the call with the bomb threat. You ask, “What did the caller say?” The clerk answers, “All he said was, ‘Get everyone out of there, a bomb’s going to go off.’” You ask, “Were those his very words?” and the clerk says “Yes.”

That’s a dramatic quote. It’s so dramatic that it deserves to be repeated on the air word for word. Why? Well, read the following sentences aloud and listen to the difference between a paraphrased summary and the quote itself:

Paraphrase:

The clerk says the caller told her to get everyone out of the store because a bomb was going to go off.

Actual quote:

The clerk says the caller told her, quote, “Get everyone out of there, a bomb’s going to go off.”

Paraphrase:

According to the clerk, the caller said that everyone should get out of there because a bomb was set to explode.

Actual quote:

According to the clerk, the caller said, and I quote, “Get everyone out of there, a bomb’s going to go off.”

The clerk says the caller told her that a bomb was going to go off, so everyone should get out of the store.

Actual quote:

The clerk says the caller’s actual words were, “Get everyone out of there, a bomb’s going to go off.”

There’s no question which version in each set of examples is the more dramatic. And more accurate. But now that that’s clear, note that in the case of each “actual quote,” there is a word or two just before it to make it absolutely clear to the audience that the words they’re about to hear are the actual words of the man who phoned in the bomb threat. Why is that so important? Read the following sentence aloud where I don’t make it clear, and ask yourself whether the audience would know for sure that it’s an actual quote:

The clerk says the caller told her, “Get everyone out of there, a bomb’s going to go off.”

Have I set up the audience for the dramatic quote? No. Does the audience have any way of knowing that it is hearing the very words the caller used? No. Why not? Because the audience cannot see the script. The audience cannot see the quotation marks denoting the actual quote.

So the lesson is simple: when you’re quoting someone, make it clear, crystal clear, that it’s a quote. You’ve just seen three ways to do it:

• the caller told her, quote, “Get everyone out of there …”

• the caller said, and I quote, “Get everyone out of there …”

• the caller’s actual words were, “Get everyone out of there …”

There are many more ways, and I won’t try to show them all. But here are a few more examples:

• the caller said to her, in these very words, “Get everyone out of there …”

• the caller said, and this is a quote, “Get everyone out of there …”

• what the caller said, word for word was, “Get everyone out of there …”

By the way, while you should prepare the audience for an actual quote, in general practice you do not specifically have to tell the audience where the quote ends. In other words, do not write (or say) something like “end quote.” Leave that to the anchorperson to achieve with voice inflection.

Speaking of voice inflection, sometimes the anchor’s or reporter’s voice inflection alone can clearly convey to an audience that the words they’re hearing are someone else’s actual words. For instance, one of my Emmy Awards is for one week’s coverage of a terrible earthquake in the Appenine Mountains of southern Italy. It was a major story because it killed about two thousand people. But the single most dramatic piece I produced was about just one victim, a woman named Lisa. She had been buried for three days when searchers barely heard her make a noise, somewhere deep down in the rubble of a three story apartment building. Then, for six hours, stick by stick, stone by stone, rescuers dug to save her. If they broke the wrong stick or moved the wrong stone, the whole pile of rubble might have collapsed, burying Lisa even deeper, and them on top of her.

But despite the danger, one worker after another dug head-first, upside down in the hole, when at a certain point one of them pulled himself up and shouted, well, let me reprint that part of the script here, so you can see the quotation marks and realize that it would have been awkward to use “quote” or “word for word” or any other verbal signal. I did it strictly by raising both the timbre and tempo of my voice:

This rescue worker cut up his face but said, “I touched Lisa’s hand, my blood doesn’t matter.”

So yes, sometimes mere voice inflection works. But don’t count on it. Unless a verbal signal would detract from the drama, better to be safe than sorry.

What’s the Point?

If someone’s words are worth quoting, then you want to be sure that the audience knows it’s hearing those actual words, rather than a summary. So make it clear. Leave no doubt.

The Final Potpourri

When I type up a syllabus for my own students at the University of Colorado, I always make a point of telling them—as I told you at the very beginning of this book—that “syllabus” is the kind of word you never should use in a script. Likewise, “potpourri.” Not everyone knows what it means and, what’s more, it’s not strictly an English language word.

But you probably understand it. A “potpourri” is a miscellaneous collection of some kind. This final section of the chapter is a collection of all the little items that don’t neatly fit into the other sections in this chapter. They’re pretty short, so I’ll simply list them as bullet points.

• “It’s” means only one thing: “it is.” It isn’t the possessive form of “it,” as in, “The dog put its paws in the water.” You may or may not understand why not, but make sure you understand this one thing. Unless you’re contracting “It is,” there is no apostrophe in “its.”

• “None” is singular. So if you’re writing about members of a jury that has just acquitted someone on trial, you don’t write, “None were convinced of his guilt.” That makes it plural. Instead write, “None was convinced of his guilt.” Or if you want to tell me that not a single reader understands this sentence, don’t write, “None understand the sentence”; write, “None understands the sentence.” An easy way to remember this is to think of “none” as “no one.” You wouldn’t write “No one understand the sentence,” would you?

• If your city council or state legislature or congress is considering legislation, they are considering a “bill.” When and if the mayor or the governor or the president signs it, then—and only then—it’s a “law.”

• Nothing “claims the life of 15 people.” Not a hurricane, not an air crash, not a disease, not a war. That’s because we’d never say it this way in conversation: “Gee, did ya hear, a hurricane claimed the lives of 15 people today down in Mississippi.” No, the way we’d say it is, “A hurricane killed 15 people.”

• When the police have picked up a man they believe committed a crime, he is only a “suspect.” When can you accurately call him a “rapist,” a “robber,” a “murderer,” or whatever? Only after he has been convicted in court. You can refer to him before the end of a trial as “the alleged robber” or “the suspected robber,” but be very careful not to convict someone before a judge or jury does.

• No one “authors” a book. Someone “writes” it.

What’s the Point?

It’s easy to look silly if you don’t think smart! And write smart too.

Exercises to Further Hone Your Writing Skills_________

1. The Never Ending Story

Here it is again, the Never Ending Story. Rewrite it again by using what you have just learned. Don’t make any other corrections. There’s still more to come.

In a place where a rear-ender traffic accident is usually the biggest event of the day, there has been an event with an impact on everyone. Tonight the lives of three people have been claimed by a bomb, which set off a three-alarm fire that raised temperatures to almost 200-degrees at a clothing store in the heart of Fort Stutter, California, the police say. No group has taken credit for the blast, but forensics experts tonight are combing the scene of the attack. In case there is more danger there, a hazardous material team is dispatched to the scene. To explain why there was not a warning, the police chief of the city of Fort Stutter, Jazibeauz Perez (JAZZ-uh-boo PEAR-ehz), says there was definitely no sign that the bomb was going to explode, then he said, “Everyone wishes to God we’d known this was going to transpire.” The police department hasn’t asked the F-B-I for help, the chief says. The dead include Jason Jones, Sally Smyth (Smith), and Greg Goldstein (Gold-steen). None were employees at the bombed store. Two unidentified men are in critical condition, meaning they might die too. Everyone in Fort Stutter is scared now to go out on the street, and city officials say increased protection will cost the people of Fort Stutter a lot of money, more than six million dollars. There is no date set for a decision about spending that amount of money, but the mayor cannot be back in town by Tuesday, which is not early enough for her critics. Whether it really will be helpful remains to be seen.

Using a different setup word or words in each case, rewrite these sentences to make it perfectly clear to the audience that the words within the quotation marks are the actual words of the person being quoted, not just a paraphrased version:

• The fireman said “There have never been hotter flames in an apartment fire here.”

• The bank teller insists the man told her “All the money has to go into the bag or some people are gonna get shot.”

• A witness at the airport screamed “The plane was heading right for the control tower, and it seemed to be on fire.”

• The mayor was mad enough to say “There’ll be no more concerts in the park, and that’s final!”

3. Killing the “Pot” in “Pourri”

Each of these sentences has a single mistake you have learned in this chapter to recognize. Correct it in each:

• None of the students were in class.

• Both movie stars are in fair condition, so they’ll probably be released soon.

• The stadium is the biggest in it’s state.

• The senator authored the bill herself.

• 18 new stop signs will be installed within a month, the traffic department promises.

• The march attracted somewhere between ten and twenty thousand protestors.

• No one has taken credit for the bombing at the restaurant.

• The thief will be put on trial next month.

• Rescuers extricated four people from the collapsed building.

• Congress is considering a law that would allow guns in airplane cockpits.

• The fire chief says the furnace exploded at exactly 8 o’clock.

• The 120 workers at the factory will share the two-million-dollar reward.

4. Writing Right

This paragraph is full of mistakes, the kinds of mistakes you should catch by now from the first few chapters of the book. It contains grammatical mistakes, style mistakes, and proofreading mistakes. Rewrite the paragraph so it has none.

The fire in City Hall destroyed it’s dome. As the wreckage fell to the ground, a group of tourists had to run for their lives, witnesses said. None were killed, but several had to be taken to the hospital, where doctors say two of them are in critical condition. So they could die, which would turn this into a murder investigation. The arsonist already has been caught, but police are questioning him carefully because after his arrest, someone else called a local newspaper to claim credit. Fire officials say it took four hours to put out the last of the flames. They also say this might not have happened if the City Council had not passed the bill that makes it legal to buy dynamite.