2

The Wrong Way to Write It

What You’ll Learn________________

The basic lesson of the last chapter was don’t use words in a news story that are so arcane, exclusive, or complicated that you wouldn’t use them in a conversation with your mother, your roommate, or your best friend. The lesson of this chapter is don’t use anything in a script you’re preparing for someone else that you wouldn’t want in a script that you might have to read, live, on the air.

What’s the difference? Simple. When you have a personal talk with someone you know—on the phone or across a coffee table—you probably don’t give a moment’s thought to how you look, how you sound, how long you take to state your point or how you form your sentences.

On the air though, no one has that casual and careless luxury. No matter who’s doing the reading, it has to be flawless: no unintelligible explanations, no tripping on the tongue. The script has to be clear and clean. But this is more easily said than done. Why? Because the anchorwoman has a lot more to do than simply read the script.

If she’s on TV, she’s also trying to watch the studio floor manager giving her a silent count-down with his fingers so she hits the tape package the very moment she’s supposed to, while she’s also trying to absorb the words of the producer in her earpiece who’s telling her to skip the next story in the script because the show is running too long, while she’s also trying to watch the monitor concealed in her anchor desk to make sure she’s looking into the right camera lens, while she’s also trying to do what the audience wants her to do: look cool and comfortable and completely in charge. If she’s on the radio, she doesn’t have to think about eye contact, but in addition to all those other things, she probably has to personally cue up the next audio sound bite and be prepared to push the right button to play it, all while reading her script with confidence and certainty. So when the anchorwoman, especially on television, works hard to look and sound authoritative (meaning she wants the audience to believe she knows the story intimately, and needs only briefly to even consult the script she holds in her hands), she’s going to be mighty embarrassed if some small visual flaw you allowed to make it onto the teleprompter causes her to bungle her words and have to start the sentence again. It just doesn’t look professional, does it?

What you’ll learn in this chapter, “The Wrong Way to Write It,” is how to minimize those embarrassments, and perhaps any threats to your job security if you’re responsible! You’ll learn when to abbreviate (almost never), when to use contractions (almost never), when to use perfect grammar (almost always), and how to deal with numbers, symbols, commas, words you want to emphasize, words you don’t want mispronounced, and references to time.

The Terms of the Story_________________________

As you read through this book, mostly in later sections about production, you’ll come to terms you probably haven’t seen before, usually terms exclusive to broadcasting. In chapters where they show up, there’ll be a glossary, here near the top of the chapter, defining these terms. That way, when you come to them, you’ll already know what they mean.

In this chapter, there are just a couple:

Sound Bite The parts of a story in which we hear someone or something other than the reporter.

Teleprompter A mirror device that hangs below the lens of a television camera and reflects the script (scrolled electronically by an operator in the control room) onto a piece of glass directly in front of the lens, so the anchorperson can appear to be talking directly to the viewer without frequently referring to the printed script in his hands.

The Never Ending Story

As you read in the first chapter, one way Better Broadcast Writing, Better Broadcast News teaches you how to write for radio and TV is recurring versions of the Never Ending Story, which is deliberately written as poorly as possible. At the end of the last chapter, your job was to improve the words in the story (but nothing else); your improvements more or less should match what you see below.

Yet this “improved” version of the Never Ending Story still is not even close to being good enough to read on the air. Your job now is to review your improved version and compare it to this one (and if you missed any major corrections, think about why you did).

Then at the end of this chapter, your job will be to correct the additional errors you’ve learned to recognize here—errors that could twist the anchorwoman’s tongue into the shape of a pretzel and embarrass her on the air—but remember, you should make changes based only on this chapter’s lessons. Don’t peek at the next chapter yet, because the version at the beginning of that chapter will show the improvements that you should have learned to make in this chapter. Slowly but surely, you’re going to turn this poorly written news report into something worth reading on the air!

In a place where a rear-ender traffic mishap’s accident’s usually the most consequential biggest event of the day there’s been a huge occurrence event with a terrible impact on each and everyone. Tonight the lives of three persons people were have been tragically claimed by a bomb, which set off a 3-alarm blaze fire that raised temperatures to almost 200° Fahrenheit at a garment clothing store at 3645 Main Street, in the heart of Ft. Stutter, Calif., the police said say. No group took has taken credit for the horrific blast, but forensics experts are combing the scene of the senseless attack tonight and in case there’s more danger there, a hazmat hazardous material team’s dispatched to the scene. They’re driving three separate emergency vehicles to get there. In order to explain why there wasn’t an admonition warning, the police chief of the city of Ft. Stutter, Jazibeauz Perez, claims says there was definitely no indication sign that the explosive device bomb was going to detonate explode, then he said, “Everyone wishes to God we’d known this was going to transpire.” The police dept. hasn’t asked the FBI for help the chief said says. The deceased dead includes Jason J. Jones, 29, Sally S. Smyth, 24, and Greg G. Goldstein, who died at 22. None were employees at the bombed store. Two unidentified men are in critical condition, meaning they might die too. Everyone in Ft. Stutter is absolutely petrified scared now to go out on the street, and city officials admit say increased protection will cost the population people of Ft. Stutter a lot of wampum money, $6.1-million. There isn’t a date set for a decision about expending spending that aggregate amount of money, but the mayor can’t be back in the community town by Tues., which isn’t early enough for her critics. Whether such an expenditure’ll it’ll really be beneficial helpful remains to be seen.

Don’t Abb.

“Abb.” can be an abbreviation for “abbreviation.” Did you fail to recognize “abb.” for “abbreviation”? Did you mistake it for something else? Or didn’t you even have a clue? That’s why you shouldn’t abbreviate.

Here’s a fairly obvious example: you are writing about a flood in Missouri, and in keeping with how we address envelopes, your script says it’s in “Ft. Lupton, MO.” Unfortunately, your anchorman doesn’t know whether “MO” is Missouri or Montana. But you’re smart enough to recognize that. So you think “Well, I’ll make sure there’s no mistake. I’ll make the abbreviation longer.” You change the script to read, “Ft. Lupton, Miss.”

Whoops. Is that Missouri or Mississippi? You may know, but will your anchorman? Maybe not. Don’t abbreviate and it won’t be a potential problem. That includes “Ft. Lupton” too. Make it “Fort Lupton” and there will be no mistake.

How general is this rule for broadcast scripts? Almost absolute. This is the kind of thing that can trip up an author who leaves something out, but I’ve checked with colleagues, and all agree that the only exceptions to the “no abbreviation” rule are the following five abbreviations, four of which are personal titles:

Mr., Mrs., Ms., Dr., and St.

Why these five titles? Because we’re all more accustomed to seeing them abbreviated than fully written out. “St. Peter’s” looks more familiar than “Saint Peter’s.” “Missus” still looks like a term from The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn.

But that’s it. Don’t abbreviate anything else. Not states, not months, not organizations. Not even common abbreviations like “gov’t.” or “int’l.” Nor when the abbreviation seems obvious, like “N.Y.” Put yourself in the shoes of an anchorwoman and ask yourself, which of the following script lines is less fraught with risk?

The plane blew up over Grand Junction, Co.

The plane blew up over Grand Junction, Colorado.

This leads to another warning: when a proper name is known by its letters—for example, the F.B.I.—think of those letters as words. In the case of the F.B.I., the name therefore is three words: “F,” “B” and “I.” So when you write it in a script, you don’t write “FBI” or even “F.B.I.”; you treat it as three separate words and separate them with dashes, this way: “F-B-I.”

Therefore the huge transport aircraft flown by the U.S. Air Force isn’t a “C5A” in a script; it’s three words: a “C-5-A.” Likewise, the chief executive officer of a company isn’t the “CEO,” at least not in a script, because while the possibility may seem remote, your anchorperson might be so busy paying attention to everything else happening in the studio that she glances quickly at the script in front of her which says “CEO Jean Jimenez” and on the air accidentally says something like “Seeoh Jean Jimenez.” So on a script you’d write, “C-E-O Jean Jimenez.”

Is there an exception? Yes, as always. The United States, commonly abbreviated “U.S.,” gets abbreviated just that way: “U.S.” That’s how we’re used to seeing it, so that’s how we write it on a script.

One last lesson about abbreviations. Acronyms are not abbreviations! Therefore, the name of the space agency in the United States, NASA (the National Aeronautics and Space Administration), isn’t read as four words, “N,” “A,” “S” and “A,” because it isn’t said that way. It’s one word: “NASA.” So we write it that way. No dashes. This rule applies to all acronyms that are pronounced as a word rather than as separate letters.

What’s the Point?

Abbreviations can trip up a reader on the air. So avoid them. Learn the few exceptions above, then in all other cases, don’t abbreviate.

I Can’t Hear You

Imagine yourself in your car, listening to a radio newscast. Think of all the sounds competing with the radio for your attention: other passengers talking, the rough surface of the road, another driver honking, a loud truck accelerating, the ventilation fan blowing, and the cell phone ringing, not to mention the possibility of just plain lousy reception.

It’s the same with the TV. While you’re trying to hear a newscast, noise may be intruding from other people in your home, a ringing telephone, a ringing doorbell, a buzzing microwave, a humming air conditioner, music in the next room, sounds on the street outside, and again, the possibility of lousy reception.

The lesson? When writing a broadcast news script, you can’t use contractions. Why not? Well, pretend you’re in one of those noisy situations and someone says from your TV screen, “You can’t use contractions.” With all the distractions, you aren’t sure you heard it right. You wonder, “Did he say you CAN use contractions or you CAN’T?” Particularly with competing noise, they can sound confusingly alike.

If you need me to hit you over the head with this, pretend the guy on TV makes it even more definitive: “You can’t use contractions. And there isn’t a single exception to this rule. I wouldn’t tell you this if it weren’t true.” Now pretend there’s a baby crying and a telephone ringing in the background. Did he say “there IS” or “there Isn’t?” “I Would” or “I Wouldn’t?” “If it Were true” or “if it Weren’t?”

Sure, there’s a big difference between how we hear “I won’t” and “I will,” but there are too many contractions where the differences are subtle. Mistakes can be made, like “have” versus “haven’t.” Say them aloud, particularly with a lot of competing noise, and you’ll hear what I mean.

Of course, this contradicts the earlier rule about writing the way you talk. So be it. It’s one of those lessons you’ll find often in this book, that every rule is made to be broken. In this case, it’s broken for a reason.

So play it safe. Avoid contractions in a script. If you write something like, “You cannot use contractions, there is not a single exception to this rule, I would not tell you this if it were not true,” then despite the competing sounds of a ringing phone and a crying baby, no one is likely to mishear it.

What’s the Point?

A contraction is unmistakable to the eye, but not to the ear. Don’t take the chance that someone hears it wrong. Avoid contractions altogether.

Turning Numbers into Words

There is a simple rule about how to write numbers on a script. From 1 to 11, spell them out.

In other words, if this were a script instead of a page in a textbook, you’d write that line this way:

From one to eleven, spell them out.

Some journalists and journalism teachers think it ought to be just one to ten. I choose to go up to eleven for a simple reason: the purpose of the rule is to minimize the chance that with all the other distractions in the studio, the anchorman misreads the digit. Seen quickly, especially if the printer needs new ink, a seven might accidentally be read as a one or vice versa. A three might look like an eight. Therefore an eleven is as easily misread as a one.

Is there a rule of thumb for when a number is too small to generalize and too big to be specific? Not really. Just depend on your own sense of (1) what the audience needs to know, and (2) what the audience will absorb and remember.

This always raises good questions: “If I have, say, a death toll of 108 people, how do I write it in a script?” Here’s how:

one-hundred-eight

How about a baseball team passing the million mark in attendance when the total number of tickets reaches 1,032, 209?

one-million, 32-thousand, two-hundred-nine

Of course a good script wouldn’t give the whole number. If the story is about the team passing the million mark, then “more than a million” is the best way to say it.

And telling the time? Again, if it’s the part of a story that says, “They found the body at 8 o’clock,” write it this way:

They found the body at eight o’clock.

This is true for everything from “one o’clock” through “eleven o’clock.” You can use the number 12 in “12 o’clock” because of the “write them out from one through eleven” rule, but if it’s “12 o’clock,” you’re probably better off with either “noon” or “midnight.”

Turning $ into Dollars

Once again, put yourself in the shoes of the anchorwoman. Think about how quickly she has to glance at the script while dealing with all the other distractions. Because of this, you should not use symbols on a script. Instead, write them out. Here are the most obvious.

Write It Out

| Write | Not |

| dollars | $ |

| cents | ¢ |

| percent | % |

| and | & |

| degrees | ° |

| point | · |

If this still isn’t clear, here’s an example of each, wrong and right. You probably can see which one is easier to read. If you can’t, read them all aloud. Then it will be obvious.

The new plane costs $32,000,000.

The new plane costs 32-million-dollars.

The man killed his friend for 90¢.

The man killed his friend for 90 cents.

The government says the unemployment rate dropped to 4%.

The government says the unemployment rate dropped to four percent.

Senator Allard & Governor Owens went to Washington.

Senator Allard and Governor Owens went to Washington.

The record for this date is 97°.

The record for this date is 97 degrees.

The damage estimate reached $18.5 million.

The damage estimate reached 18-point-five million dollars.

What’s the Point?

Play it safe. Why take the chance that an anchorperson glances too quickly at a symbol and either misses or misreads it, when typing it out makes it obvious?

Sounding Smart, Saying It Right

One of the best ways to sound stupid is to pronounce a word that the audience—even just a single person in the audience—knows is wrong.

During the initial American attacks on Afghanistan at the start of the war on terrorism in 2001, for example, newspaper and magazine reporters could just write the names of places in Afghanistan and Pakistan that they never had heard of before: Herat, Kandahar, Peshawar, Quetta, Mazar-e-Sharif, even the capital, Kabul.

I say “even the capital, Kabul,” because while it’s fairly well known, it’s commonly pronounced two different ways, which I’ll put phonetically here, with the syllable that’s meant to be accented or emphasized in All Caps (all capital letters): “Kah-bool” and “kah-Bool.” Read them aloud right now so you hear the difference. It’s easy for print reporters to write about Kabul or any of those other places because for their readers, pronunciation isn’t necessarily an issue. Does Kabul have an accent on the first (“KAH-bool”) or the second (“kah-Bool”) syllable? Is Peshawar “Pesh-uh-were” or “pesh-Ow-were”? Do you use a “w” sound in Quetta to pronounce it “Kweh-tuh” or ignore it and say, “Keh-tuh?” Print reporters don’t really have to know. All they have to do is spell it right.

Broadcasters don’t have that luxury. Broadcasters have an obligation to get it right, because the way they pronounce a place name or a person’s name is the way the audience learns it. So how do you insure against mistakes? Easy. Type questionably pronounced names in the script, then in parenthesis beside it or above it, put a “pronouncer,” which means the word is shown phonetically, separating the syllables with hyphens and putting the emphasized syllable in All Caps.

You already have seen how to write a pronouncer for “Kabul.” If it’s part of a script line, it should end up looking this way (with the phonetic pronouncer either typed or handwritten in parenthesis beside or above the script line itself):

American planes have dropped ten bombs on Kabul (kah-Bool).

Let me show you how the other Afghanistani place names would be handled, not because you’ll ever have to pronounce them yourself, but because the technique I use to make them readable is the technique you should use, no matter what the word, or what the language. Simply come up with the most easily recognizable phonetic spelling, so that everyone who sees it says it the same way.

In Herat (Hair-AHT), there was no electricity.

Three targets in the provincial capital of Kandahar (Kahn-duh-har) were destroyed.

Refugees from Mazar-e-Sharif (mah-zahr-ee-shah-Reef) reported fires throughout the city.

By the way, the best way to phoneticize a syllable is to use a real word if you can, a word everyone recognizes and says the same way, like the word “hair” for the first syllable in “Herat.”

Of course it doesn’t do you or anyone any good if you put pronouncers next to words that need them but you don’t actually know if they’re correct. Good journalism demands that every time you come to a name and you’re not positive how to pronounce it, or there’s simply more than one way to pronounce it, you check.

If it’s a city, check the atlas. If that doesn’t help and it’s in the United States, call Directory Assistance and ask the local operator how to say it. Or get the number of a local shop and call there. If it’s overseas, call the Washington D.C. embassy for the country in which the place is located and ask someone there.

If it’s a person rather than a place, go to the same trouble. If it’s someone in a crime story, ask the police. If it’s someone in business, call the company. If it’s someone in politics, call the political body with which she is associated. The point is, don’t guess. Call!

The trouble is, while a place name like “Mazar-e-Sharif” may obviously need a pronouncer, there are plenty of names where it’s not so clear. For instance, if a major league shortstop is named Jose Perez, how does he say Perez: “pear-Ehz” or “Pear-ehz”? If you don’t know, you absolutely must find out.

You don’t need phonetics if you’re working with a name we all recognize. But what if the name of a spokeswoman for the Air Force is Helene Goldstein? Now you have two challenges. Is her first name said as “Helen” or “hell-Een”? And how about her last name? The first syllable is always emphasized in Goldstein, but is it “Gold-steen” or “Gold-stine”? If a last name is “Smyth,” is it a long or short “I”?

See the problem? See why it’s important to check? See why it’s important to get it right?

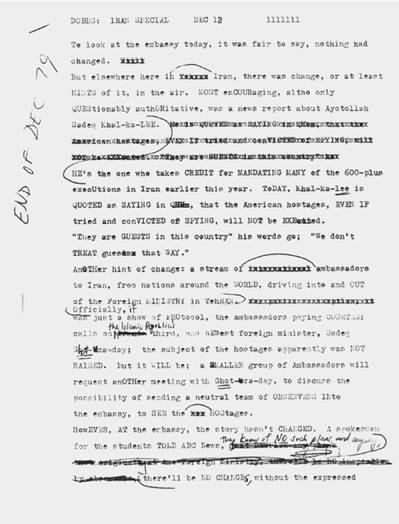

Finally, here is a picture of the first page of a script I wrote from Iran, about a month after fifty-two Americans were taken hostage by militants loyal to the new fundamentalist Islamic government there (and held for 444 days). The script is pretty sloppy, but it does illustrate “pronouncers.”

As you see, I had to say two names that were unfamiliar to me. So I tried to write them phonetically. The fact is, according to the very lessons I impart above, I didn’t do a great job of it (no one told me that someday I’d be teaching this kind of thing), but it served its purpose, which simply means I didn’t stumble and get them wrong.

What’s the Point?

If a name is mispronounced on the air, someone’s going to know (maybe a lot of “someones”). That puts your credibility, as well as the anchorperson’s, on the line, and people’s perceptions of your responsibility is shot.

English 101, Revisited

If you tell me, “I have never used a split infinitive,” I have to respond, “You have just now used one … and so have I.” Corrected to eliminate the split infinitive (where the adverb was placed in the middle of a present perfect verb), your statement should be, “I never have used a split infinitive.” Mine should be, “You have used one just now.”

But this textbook is not written for a course in English; it is written for a course in journalism. What that means is, I’m not going to give you chapter and verse about correct versus incorrect grammar. It also means that while there is a clear difference in English between right and wrong, it’s more of a grey area in journalism, especially when the emphasis is on broadcasting. Why? Because the whole principle of writing for broadcast is that you should write the way you talk—and when we talk, we use split infinitives all the time.

So the only rule I’ll lay down here is this: use good grammar unless it sounds stuffy. Unless it sounds contrived. Unless it sounds unnatural. The following sentence comes from a feature story I wrote about a new health care clinic in the Alaskan Arctic:

Nearly the whole professional staff here has recently been imported.

Read the above sentence aloud, then read the sentence below aloud too. You’ll hear that the first one—split infinitive and all—sounds conversational, the other one doesn’t.

Nearly the whole professional staff here recently has been imported.

But later in the same script, the following sentence, which obeys the rules (meaning no split infinitive), sounds perfectly fine:

They always have had a hands-on therapeutic kind of care.

What’s the Point?

Use proper grammar whenever possible. But if you have to choose between proper and colloquial, go with the latter. Write the way you talk.

English 101, Revisited Yet Again

It is easy, because of the work it takes to avoid them, especially when you’re in a hurry to make a deadline, to write with a lot of dependant clauses, which help define what you’re trying to describe.

Have you caught on to my tricks by now? That sentence you just finished reading is riddled with dependent clauses. It doesn’t have to be. Try it this way, and see whether it’s less clear or more clear:

Because of the work it takes to avoid them, it is easy to write with a lot of dependent clauses, especially when you’re hurrying to make a deadline. They help define what you’re trying to describe.

See? By splitting one sentence into two and rearranging the phrases, it’s already better. But can we improve it even more? Of course, by reworking a couple of words and creating three sentences:

It is easy to write with a lot of dependent clauses. They help define what you’re trying to describe. It takes work to avoid them, especially when hurrying to make a deadline.

Personally, I used to use too many dependent clauses myself. I didn’t appreciate the beauty of short, sharp, simple sentences. I do now.

So in the spirit of “before and after,” here are some sentences straight from my scripts, followed in each case by what I should have written.

(from a story about the presidential campaign of Colorado Senator Gary Hart)

Hart made it official Tuesday by filing in New Hampshire, but that flurry of publicity, thanks mainly to his celebrity, is really about all he has.

Hart made it official Tuesday by filing in New Hampshire. That flurry of publicity, thanks mainly to his celebrity, is really about all he has.

(from a feature about a new bank especially for children)

It’s a real bank, but kind of a huge piggybank that opened here, one that caters to a special age group, one whose customers seem to really understand the current value of the dollar, one where the signature card is a brand new experience.

It’s a real bank, but kind of a huge piggybank that opened here. It caters to a special age group. Its customers seem to really understand the current value of the dollar. For them, the signature card is a brand new experience.

(from a story about a medical funding crisis in Oregon)

With two-year-old David’s life on the line with leukemia—he still needs a bone-marrow donor—his mother left home behind and uprooted from Oregon to Washington state, which helps pay for life-saving transplants.

Two-year-old David’s life is on the line with leukemia. He still needs a bone-marrow donor. So his mother left home behind and uprooted from Oregon to Washington state. Washington helps pay for life-saving transplants.

(from a feature about avalanche control)

While safety officials fight a perennial war against avalanches, trying here for instance to provoke one under control, they’re the first to admit, with 14-million acres of forest service land alone, that their procedures are far from foolproof.

Safety officials fight a perennial war against avalanches. They’re trying here for instance to provoke one under control. But with 14-million acres of forest service land alone, they’re the first to admit that their procedures are far from foolproof.

(from a story about a hijacked Kuwaiti Airlines 747 that ended up in Algeria)

About an hour after the Kuwaiti plane pulled up, so did a private jet, the Algerian president’s jet one of my sources tells me, which immediately got stocked with food and fuel, and this matched everything we had heard about the hijackers’ plans, although those reports were only second hand.

About an hour after the Kuwaiti plane pulled up, so did a private jet. One of my sources tells me it was the Algerian president’s jet. It immediately got stocked with food and fuel. This matched everything we had heard about the hijackers’ plans, although those reports were only second hand.

What’s the Point?

As you have read several times now, keep your sentences short, sharp, and simple. Keep dependent clauses to a minimum. The other point is be careful how sloppily you write scripts because, like me, someday you might have to put them on display in a textbook!

When Time Doesn’t Matter

Here’s a rule that’s simple to state but harder to follow: Never start or end a sentence with a time reference.

So this is inferior:

This morning there was a three-car crash that stopped traffic on I-80.

And so is this:

There was a three-car crash that stopped traffic on I-80 this morning.

This is superior:

There was a three-car crash this morning that stopped traffic on I-80.

Why are the first two examples inferior and the last one superior? Not because the first two are grammatically incorrect, but because the time of the crash and the traffic tieup isn’t the most important fact in the story. Sometimes it is even irrelevant. If you’re reporting it, it’s implicit at least that it’s today. What is most important? Obviously the crash, and the tieup. That’s why you should bury the time—“this morning,” “tonight,” “yesterday,” “tomorrow,” “next week,” “last month,” etc.—somewhere in the middle of your sentence.

There’s another reason for the rule too. A good story, like a good newscast, begins and ends with something that has an impact on the audience, something you want them to remember about the day’s news. Well, guess what! A good sentence begins and ends that way too. What most likely has that kind of impact? What should the audience carry away from your reporting? Certainly not the time the story happened. No, you want them to remember the story itself.

Just to make sure you know the difference, read (aloud) and think about the following examples. Which ones deliver more impact from the most important facts?

The Dow Jones Industrials rose 120 points today.

The Dow Jones Industrials today rose 120 points.

Next week the president will fly to Moscow to negotiate arms reductions.

The president will fly to Moscow next week to negotiate arms reductions.

The Yankees’ star pitcher will sign for thirty-million-dollars-a-year tomorrow.

The Yankees’ star pitcher tomorrow will sign for thirty-million-dollars-a-year.

Last night 180 people died in a plane crash.

180 people died last night in a plane crash.

Like I said, it’s an easy rule to state, harder to follow. So here’s one more way to think about it: if you have to include a time reference in a sentence, write it so that if you removed the time reference from the middle, the sentence still would tell the basic story. And although there are exceptions, here’s an easy way to apply it: try to put the time reference as close a possible to the verb.

Is this the first rule of the book that has no exceptions? Of course not! Sometimes the time something happens (or will happen, or has happened) is the most critical fact. For instance, if a murderer whose crime and trial have been well covered by the media finally is due to be executed tomorrow, then “tomorrow” is the big news. Thus:

The man who killed four children in his backyard a decade ago will be executed tomorrow.

Or, needing no explanation:

Today the world will end.

Need I say more?

What’s the Point?

Despite the example above, the world will not end today. Almost always, bury the time reference.

The Important Thing, About Commas

Stop thinking about commas as commas. In broadcast newswriting, practically speaking, commas can serve an entirely different—and more important—purpose than however you used to use them. This might not turn up in other broadcast newswriting textbooks, but trust me, it can help: from now on, don’t think of commas as commas, think of them as pauses. They just look like commas.

For instance, take a look at this paragraph, from a documentary I did about dangers in the American workplace. For once, do not read it aloud; just look, and see how many grammatically incorrect commas you spot.

The Veterinary School at the University of Florida is a classic, sick building. Erected in this age of energy conservation, it is deliberately sealed, to the outside. This means everyone inside depends on a mechanical ventilation system for the very air, they breathe. Sounds safe! But what inspectors found in the system here, was a sickening mold growing, in the ducts. What they found elsewhere, sounds even worse.

Did you spot an unnecessary comma or two, or six? Well yes, there are six unnecessary commas if you think of them as commas. But think of them instead as something else: pauses. Think of them as a sign to you, or to whoever is reading the script, to stop for a dramatic beat—some might say a “pregnant pause”—to let something sink in. Now, here’s the same paragraph. Instead of looking, read it aloud, pausing where those “commas” appear to be.

The Veterinary School at the University of Florida is a classic, sick building. Erected in this age of energy conservation, it is deliberately sealed, to the outside. This means everyone inside depends on a mechanical ventilation system for the very air, they breathe. Sounds safe! But what inspectors found in the system here, was a sickening mould growing, in the ducts. What they found elsewhere, sounds even worse.

Everyone’s reading style is different. Yours may not be anything like mine, which means you might not place commas where I place them, or you might not pause where I pause. This isn’t practiced in every broadcast newsroom, but it might be useful in yours to know that a comma no longer has to be a comma in a broadcast news script; it can be a pause.

Sometimes, however, this is more easily said than done. If you work in the print media and want to write about “Omaha, Nebraska,” you write it precisely that way, with a comma between the city and the state. But in broadcast news, you don’t pause between the two like this:

Two trains have collided head-on in Omaha, Nebraska.

Therefore, you do not insert a comma; write it instead like this:

Two trains have collided head-on in Omaha Nebraska.

When you proofread your script, add the concept of “commas-as-pauses” to the list of things for which you must be alert. If there’s a comma there that shouldn’t be there, the anchorperson probably will pause and sound silly. If there’s no comma where there ought to be one, well, the result could be the same. Don’t let it happen. Put in commas where you want pauses, and take them out where you don’t.

What’s the Point?

A script is your road map. That’s why the purpose of every piece of punctuation, like all other markings, is to make it easy to read. The commonplace comma can have a new role in your life.

Giving It Some Punch

Sometimes you really want to punch a word. In other words, emphasize it. Say it louder than the other words in the sentence. Or longer. For example, in the first sentence of the paragraph you’re reading right now, if you’re reading it aloud you want to emphasize the word “really.” So here’s the easiest lesson in this book. When you want to punch a word, either underline it or type it in All Caps. Therefore:

Sometimes you really want to punch a word.

Or:

Sometimes you Really want to punch a word.

This helps the anchor or the reporter finesse the sentence when reading it into the microphone. But this can be overdone. I’ve been as guilty as anybody. I used to isolate specific syllables I wanted to emphasize. Not whole words, just syllables. When I’d send a script to ABC News in New York, the producers made fun of my typing style. Here’s how a typical sentence looked:

By this MORNing, most homeless surVIvors, it appEARS, have at least CANvas overhead, food and WATer in their STOMachs.

My bosses in New York loved this particular story, but sent back a response dripping with visual satire. It looked something like this:

“SuPERB… CLASSy… SENsitive. We were VEry PROUD.”

What’s the Point?

If you want to make sure the right words get the right emphasis, make it clear on the script. But save it for the really important words, not every syllable. Too much, and it looks silly.

Exercises to Hone Your Writing Skills_______________

1. The Never Ending Story

Here it is again, the Never Ending Story, just like what you saw at the beginning of this chapter but this time, the lessons of the first chapter have been applied. Your job now is to rewrite it again, applying the lessons of this second chapter—avoiding contractions, clarifying pronunciation, checking for commas, eliminating extraneous information, and so forth. As before, don’t peek yet at the next chapter, because that will show the improvements that you should have made in this chapter.

In a place where a rear-ender traffic accident’s usually the biggest event of the day there’s been a event with an impact on everyone. Tonight the lives of three people have been claimed by a bomb, which set off a 3-alarm fire that raised temperatures to almost 200° Fahrenheit at a clothing store at 3645 Main Street, in the heart of Ft. Stutter, Calif., the police say. No group has taken credit for the blast, but forensics experts are combing the scene of the attack tonight and in case there’s more danger there, a hazardous material team’s dispatched to the scene. They’re driving three separate emergency vehicles to get there. In order to explain why there wasn’t a warning, the police chief of the city of Ft. Stutter, Jazibeauz Perez, says there was definitely no sign that the bomb was going to explode, then he said, “Everyone wishes to God we’d known this was going to transpire.” The police dept. hasn’t asked the FBI for help the chief says. The dead includes Jason J. Jones, 29, Sally S. Smyth, 24, and Greg G. Goldstein, who died at 22. None were employees at the bombed store. Two unidentified men are in critical condition, meaning they might die too. Everyone in Ft. Stutter is scared now to go out on the street, and city officials say increased protection will cost the people of Ft. Stutter a lot of money, $6.1-million. There isn’t a date set for a decision about spending that amount of money, but the mayor can’t be back in town by Tues., which isn’t early enough for her critics. Whether it’ll really be helpful remains to be seen.

2. The Ever-Improving Story

Write a better broadcast version of the following sentences (as in the first chapter, your instructor may want you to read the old version and your new version aloud in class, for everyone to hear the difference between them):

• The plane exploded over Long Island, N.Y.

• The police cornered the suspect at the end of an asphalt alley.

• The stock market fell 13% today.

• Both cars had been parked downtown and both drivers had been working.

• The new 85,000 pound helicopter costs $6,032,425.

• The new law isn’t going to make a big difference in people’s lives.

• Jason L. Septeimeer, 28, was killed by a drunk driver tonight.

• The terrorist said he wouldn’t surrender his AK-47.

• Today in Sacramento three legislators came down with food poisoning and one of them claimed he felt ill for two hours before calling a hospital, and the others said they couldn’t identify the cause.

•The space agency NASA is cooperating with the FBI to reduce theft at its Fla. headquarters, which has passed the $1,000,000 mark.

3. The Rewritten Story

Write a better broadcast version of the following stories:

• Airport officials said a 737 slid off the runway in snowy conditions during the snowstorm that hit the eastern part of the city tonight. They stated that conditions on the runway were known to be slippery but that there hadn’t been accidents before the 737 went into its skid. The repairs to the runway according to airport officials will come to more than $250,000.

• The Mayor has certainly never been convicted of theft, but questions still came up about his CV. The Mayor’s critics especially councilwoman Rebot, who was wearing a tan dress while she spoke, contend that the Mayor has probably hidden dark secrets from his past and don’t think he has revealed everything, and they fear the public will lose faith in gov’t.

4. The Restated Questions

• What five words can you abbreviate in a broadcast script (you can answer with their abbreviations)?

• If a fire department spokesman says the damage estimate from a fire is “$3,968,200,” how do you simplify it?

• Why do you hyphenate “F-B-I,” “C-I-A,” and the abbreviated names of other such agencies?

• Why are contractions like “isn’t,” “wouldn’t,” “can’t,” and others dangerous in a broadcast script?