11

The Correct Corrections

What You’ll Learn_________________________

There are few things more embarrassing to a broadcaster on the air than coming to a typo on a script, and finding his tongue toed up in knights. Oops, sorry, I mean, tied up in knots. (Lucky that I caught that!)

You wouldn’t expect it to happen if someone has carefully proofread the script, as you were taught to do in the last chapter. But it does, for several reasons. Sometimes it’s because, well, someone (you) hasn’t proofread well enough. And sometimes it’s because someone (you again) has carelessly corrected it in ways only a Martian could understand.

It’s easy enough to make these mistakes. But it’s not acceptable. Here’s the good news though: it’s easy to avoid them. In the last chapter, you learned how and why to proofread. In this chapter, you’ll learn how and why to make proper corrections if proofreading, somehow, has failed.

Bringing Out the Worst

I’ve written a story. Oh, it’s fictional, but it’s good. Very good. As you’ll see, it’s about a fatal plane crash. Among others, the airplane was carrying singing sensation Rock Starr. Along with the other passengers, Starr was on a humanitarian mission from the United States to Russia. I could tell you more, but you’ll read it all in the story, which I have written flawlessly. Well, almost flawlessly. If you look hard, you might find a few flaws I missed.

I’ve put it in a box, and left plenty of space between the lines, because I want you to correct whatever careless mistakes or poor writing you find. Don’t rewrite the story on a new sheet of paper; make your changes and corrections on the script in the box. If you don’t think you’re going to sell this book to someone else when you’re through with it, go ahead and make the corrections right here on the page. If you don’t want to do that, photocopy the box and work from the copy you make. But whatever you do, do NOT read beyond the box. Not yet.

Today sinker Rock Starr died at 28, and 11 people, 6 males and 5 females, were also killed too today when a US Airforce C5A transport carrying the singing sensation and the others tragically crashed today in NY’s Long Island Sound. The plane, based at Lake Champlain Ill., had been flying at 43,000 ft. at the time, carrying the volunteer workers and supplies to an air base in Leningrad where a dam building project is underway with US help. Analysts conclude that altitude is a dangerous one is a dangerous one to fly at. The spokesman for the AF, Chris Goldstein, estimates that the loss to the govt from this mishap is estimated at $29,037,292. “We pride ourselves for our air skills, and we’re flat-out shocked by the crash,” the Air Force Chief of Staff told reporters at the Pentagon.

Okay, did you make any changes? I sure hope so, because the piece as originally written wouldn’t pass muster in a fourth grade writing class. Luckily for you, previous chapters in this book have armed you to find just about all the flaws that I missed.

The first ones probably were obvious, for instance, absurdly repetitive language:

• The word “today” shows up three times in the first sentence. It should appear only once, and certainly not at the very top of the story. That’s another rule you should remember.

• In the phrase, “… 11 people… were also killed too today…” we don’t need “also” and “too” in the same sentence.

• “Analysts conclude that altitude is a dangerous one is a dangerous one to fly at.” If you didn’t catch the repetition here, you need to re-read the last chapter on proofreading aloud! (Do you remember now?) And by the way, do we really want that sentence to end with a preposition?

• Here’s another repetition that’s not quite as easy to catch, but you should have caught it anyway: “The spokesman for the AF, Chris Goldstein, estimates that the loss to the govt is estimated at $2,037,292.” He “estimates” that the loss is “estimated at…” Ugly!

You’ve also learned a lot of things in previous chapters that should have helped you catch and correct the following:

• If you’re going to break down the gender of passengers at all, “… 6 males and 5 females” should be “… 6 men and 5 women.” But that’s not all. As you know by now, we spell out numbers from 1 to 11. So it ought to read, “… six men and five women.”

• While we’re at it, you should have corrected “11 people” to read, “eleven people.” But here too, there’s more. According to the story, Rock Starr died, and “11 people… were also killed.” But unless his music was even worse than I think, Starr himself was human, so it’s “eleven other people.” It required clarification.

• Speaking of spelling out numbers, you should never leave a long numerical figure like “$29,037,292.” How to correct it to make it readable on the air? “29-million-37-thousand-two-hundred-92-dollars.” (Notice that I change the dollar-sign symbol to the word “dollars” too.) But wait. Do we really need the loss, right down to the dollar? Of course not. You can round it off to “about 29-million-dollars.” And while we’re on a roll, “43,000 ft.” should have been “43-thousand ft.”

• But of course, “ft.” is an abbreviation that shouldn’t appear in a script. So it should be, “43-thousand feet.” Likewise, “Ill.” should be “Illinois,” “NY” should be “New York,” “gov’t.” should be “government” and “AF” should be “Air Force.”

• There are a couple of names that require pronouncers. Does everyone know how to pronounce Lake “Champlain?” Probably not. And how about the name of the Air Force spokesman, Chris Goldstein? Does it sound like “Goldsteen” or “Goldstine?”

• Remember “6 males and 5 females?” Maybe you don’t need that kind of detail at all. What’s important is how many people died, not a breakdown of their genders. That may be Too Much Information (TMI)!

• Since we’re talking now about TMI, how about the name of the Air Force spokesman? Whether it’s pronounced “GOLD-steen” or “GOLD-stine,” we really don’t need it at all. He’s a spokesman; his name doesn’t matter.

• There may be a few other cases of TMI, such as where the plane was based, what the people were going to help build in Russia. But facts like that might be important to some members of the audience, so whether they’re important enough to keep is subjective.

• A cousin of TMI is “trash.” When the sentence in the story reads (after removing the repetition pointed out earlier), “… analysts conclude that altitude is a dangerous one to fly at,” did you think, “I should kill the words ‘to fly at’ because they add nothing?” You should have. “Analysts conclude that is a dangerous altitude” is enough.

• Did you change “Analysts conclude…” to “Analysts say…”? Should have! Write the way you talk.

• Likewise, if you wouldn’t use “mishap” in normal conversation, don’t use it in a script. So the “mishap” was a “crash.” (And be careful about something else. It was not necessarily an accident. We don’t know why the plane went down.)

• The plane “tragically crashed,” according to the original. Maybe even according to everyone you might have spoken to about the crash. But don’t get in the habit of using judgmental words, even when the judgment probably is universal. Kill the adverb. Anyway, everyone knows a plane crash is tragic, and doesn’t need you to explain it.

• If someone doesn’t know what a C5A is, then she might misread it on the air. Remember why? Because it’s actually read as three words. That’s why “FBI” should be “F-B-I” on a script. Likewise, the “C5A” should be hyphenated on the script to read, “C-5-A.”

• In the last line of the original story, there are two mistakes you should have caught:

1. If you choose to use it, then you have to make clear to the audience that these are the very words of the Air Force chief of staff—this alone probably makes it worth using.

2. The quote, followed by the reference to who said it, is old-fashioned print style. We don’t talk that way, so we don’t write that way for broadcast. Therefore, if you choose to use it, the way to change that sentence would be along the lines of, “The Air Force chief of staff says, and I quote, ‘We pride ourselves for our air skills, and we’re flat-out shocked by the crash.”’ And this leads to yet another point: in the original, he “said,” but because it’s recent and the gist of his statement hasn’t changed, you can make it “says.”

Finally, without the benefit of what you’re about to learn in this chapter—which will help you turn this molehill into a mountain—you should have caught a few other flaws deliberately built into the story:

• You don’t want the anchorperson to sound like he is swearing… . so you don’t want little traps like “… where a dam building project is underway with U.S. help.” If you want to mention the project at all, you should correct it to read something like, “… where the U.S. is helping to build a dam.”

• “Leningrad” isn’t Leningrad any more. It is “St. Petersburg.” The name was changed after the Soviet Union, founded by Lenin, fell. You don’t know that from this book, but you ought to know it from your class in geography.

• Oh, and maybe at the very top of the story, you noticed the typo “sinker.” Knowing that Rock Starr was a “singing sensation,” you should have corrected it to read, “singer.” If you’re still on the computer, the correction is simple to make. If you’re working from a page you’ve already printed out, there’s a right way and a wrong way to make even a simple correction like that. By the end of this chapter, you’ll know how.

Okay, that pretty much covers it. Although you probably found many of these flaws and made corrections, chances are you didn’t find them all. So here’s another box, with the same story in its original bad form. Correct it again, knowing now of all the flaws built into it. Why do it all again? Because this chapter isn’t just about finding the flaws; it’s about how to make corrections in a universally readable way. What this means is, when you have finished the chapter and, near the end, made these corrections a third time, you’ll be surprised at how much easier they are to follow.

Today sinker Rock Starr died at 28, and 11 people, 6 males and 5 females, were also killed too today when a US Airforce C5A transport carrying the singing sensation and the others tragically crashed today in NY’s Long Island Sound. The plane, based at Lake Champlain Ill., had been flying at 43,000 ft. at the time, carrying the volunteer workers and supplies to an air base in Leningrad where a dam building project is underway with US help. Analysts conclude that altitude is a dangerous one is a dangerous one to fly at. The spokesman for the AF, Chris Goldstein, estimates that the loss to the govt from this mishap is estimated at $29,037,292. “We pride ourselves for our air skills, and we’re flat-out shocked by the crash,” the Air Force Chief of Staff told reporters at the Pentagon.

Good. Now just one more exercise to complete this section. Pretend you’re an an-chorperson. Read what you’ve just corrected as if you’re on the air. If anything makes you stumble—anything—then you need to correct your corrections. That’s what you’ll learn to do in the rest of this chapter.

What’s the Point?

Writing a story by the rules is one thing. Having a readable copy on the air is another. Most of the time, corrections will be made in the computer. But you might be working with a printed copy and correcting it at the last minute, or handing your corrected copy to someone else to put back—properly corrected—into the computer. It must be clean and comprehensible to whoever gets it.

Just Follow the Roadmap

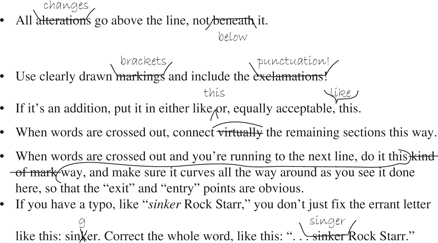

A script is like a roadmap. Sometimes, as you just read, it’s going to get all marked up. But if everyone uses the same lines, the same signs, the same symbols, it shouldn’t be a problem. Everyone will be able to read everyone else’s script.

I can’t guarantee that every producer in every newsroom will agree with the universal appeal of the formats you’re about to learn. Some, in fact, may have been educated in and adhere to another organization’s rules of style. If so, then needless to say, do it the way they do it there. But by and large, the rules you’ll read here will serve you well.

Since I covered most of what you need to know already in earlier chapters, we’re down to just the mechanics of corrections, the proper format. There are just a few rules to learn. They ought to become second-nature to you, because if you haven’t learned them well before a script goes into the studio, it may be too late.

The whole purpose of the exercise is this: the script must be clear and clean enough to read on the air, even if the person reading it hasn’t seen it before! What this means is, whether your manual markings are in someone else’s hands to enter in the computer or to read from a printed page at the last minute on the air, they should be easy for anyone to figure out.

What’s the Point?

The point is what I wrote at the beginning of this section: a script is like a roadmap. Make sure that if you have to manually mark a script before it’s read on the air, anyone could find his way.

Corrections From the Front of the Class

The word “corrections” cuts both ways. It also refers to the corrections your instructor makes on scripts you turn in for assignments.

I’ve developed my own system of corrective marks, which I explain (in a handout) to students at the beginning of the semester. Then, instead of writing on every careless mistake something like, “Pay more attention to accuracy,” or “Shouldn’t you just round off this number?” or “Remember to hyphenate because it’s actually three words when spoken aloud,” I can just write (in these particular cases), A, RO, or H respectively. As you’ll see, it’s simply a series of letters, pointing to mistakes students make.

Each instructor’s system is unique. But I’m showing you mine to underscore the variety of mistakes that turn up. They should have been caught by the writers in the proofreading process. You should catch them before turning anything in, especially when your job could depend on it!

A ACCURACY is the most important thing in journalism. If you write well but are inaccurate, you’re the world’s worst journalist. Pay attention to facts. Don’t get them wrong, and just as important, don’t tell more than you know. If you have this letter on your script, it’s because something is inaccurate.

AV ACTIVE VERBS make the script come alive (“A man was killed by a bomb,” versus “A bomb killed a man.”)

C COMMAS In broadcast copy they are not necessarily used for grammatical punctuation; rather, they can be used as a sign to the newscaster to pause. If there isn’t a comma where there should be one, the newscaster might not know to pause. If there is one where there shouldn’t be, the newscaster will pause where she shouldn’t causing her to sound awkward. The only way to make sure you have it right is to proofread aloud with commas in mind. You wouldn’t say, “Instructor, Greg Dobbs, told us this.” It’s “Instructor Greg Dobbs told us this.” Likewise, in print you’d write, “In Lincoln, Nebraska, three men … ” but in broadcasting you’d write, “In Lincoln Nebraska, three men…” because you’d say it that way.

CL CLOSE should tell us where the story’s going, or what it means, or wrap it up.

DIE YOU CAN’T DIE “at 28.” You can die at a party, or at home, or at the airport. If you want to give someone’s age, then write it something like this: “Rock Starr died. He was 28.” Or, “Rock Starr died at the age of 28.”

DRQ DON’T RAISE QUESTIONS you don’t answer. Either answer the question in your script or don’t raise it.

EC EXTRA CLUTTER Is it necessary to name, for example, a police spokesman? No. The important thing is that “a police spokesman says the woman was drunk.”

GA DON’T GIVE AWAY THE SOUNDBITE with your lead-in.

H HYPHENATE When we refer to a name with letters (like “FBI”), it’s “F-B-I” because that’s really three words. But here’s an exception: U.S. is the proper abbreviation. (Remember, while NASA is an acronym, it’s pronounced like a word, so you don’t hyphenate it.)

JW JUDGMENTAL WORDS Don’t use them. Report, don’t comment or editorialize.

L LEAD INFORMATION must actually lead a story. If you bury a lead (somewhere in the body of the story), the audience may not stay interested long enough to hear you when you get to it. It should be the most important and/or the most interesting and/or the most immediate fact in the story. Keep it short and simple. It’s the attention grabber.

LIU LOOK IT UP if you don’t know where or what something or someplace is. New, is about facts, not fiction.

LN MAKE LARGE NUMBERS EASY TO READ, so if you have a big number like “$2.5 billion,” spell out the word “dollar” instead of using the “$” symbol, and spell out the point, so it reads, “two-point-five billion dollars.” Any number over eleven can be written as numerals. If it’s a higher number like $23.5 billion, it reads “23-point-five billion dollars.”

NA NO ABBREVIATIONS Be particularly aware of common abbreviations like states, months, and units of measurement. Write out “New York” (not NY), “foot” or “feet” (not ft. or ”), “government” (not gov’t) and “international” (not int’l). The exceptions are: Mr., Mrs., Ms., Dr., and St.

NF NO FLOW from the lead in into the sound bite.

NI DO NOT INDENT for paragraphs. It’s a news story, not a novel.

NP NO PRONOUNCER Names (and other words) must be correctly pronounced. If there’s any question about how to pronounce it, you’ve got to show it on the script! How do you know your anchor will know the correct pronunciation of “Champlain”? Or of “White House spokesman Chris Goldstein”? (Is it “Goldsteen” or “Goldstine?”) Or whether the accent is on the first or the second syllable of “Perez”? Put phonetic pronunciation in parenthesis above or right after the questionable name, putting the emphasized syllable in ALL CAPS (for example, Sham-PLANE, GOLD-steen).

NS NO SYMBOLS on scripts ($, degrees, %). Spell it out (“percent,” “dollars,” etc.)

P PROOFREAD How? Aloud! (What you’re writing is for the human ear, not the eye). If something’s not proofread, it’s sloppy. If it’s sloppy, someone’s going to screw up while reading it. If somebody screws up, the audience is distracted and you look stupid.

PA PROOFREAD ALOUD and you’ll catch mistakes that the eye won’t always catch. You’ll hear when words are overused. You’ll catch embarrassing typos and tenses that don’t match. You’ll also catch things like, “He visited that dam project in Iowa.”

PF PRINT FORMAT doesn’t cut it in broadcasting. A sentence such as, “‘I didn’t do it’, the man said” must be written for radio and TV along the lines of, “The man said he didn’t do it,” or, “The man said, and I quote, ‘I didn’t do it.”‘ Remember, write like you talk!

PT PRESENT TENSE Immediacy is most easily achieved by writing in the present tense, whenever possible. For example, it’s better to write “The mayor says…” than “The mayor said.…” At least use the present perfect when you can. “A crippled plane has landed at the airport” is better than “A crippled plane landed at the airport.”

PU PUNCTUATION In making your correction, you left out (or left in) key punctuation that will confuse, embarrass, and ultimately foul up the anchor-person, which may be you.

Q QUOTES must obviously be quotes! What this means is, if you just write: “The man said ‘I didn’t do it,” ‘the audience can’t see the quotation marks on your script, and has no idea that these are the man’s actual words. Someone might infer that the man is clearing you, the newscaster, of guilt. So make it clear. In that example, therefore, you’d want to write something along the lines of, “The man said, and I quote, ‘I didn’t do it.’”

RM ROADMAP All the markings (connecting words after you’ve crossed something out, replacing one word with another, etc.) are your roadmap. Use the uniform markings you’ve been taught. They are basic and proven, and fairly universal.

RO ROUND OFF COMPLICATED NUMBERS Think about what’s important from the standpoints of simplicity and understanding: “$2,037,292” or “more than two million dollars?” In a case like this, round it off.

SL SIMPLIFY LARGE NUMBERS like this: “43-thousand,” not “43,000.” Too many zeros for the anchor to read if there are distractions in the studio.

SLUG SLUG You need a slug in the upper lefthand corner. (You will learn about “slugs” in Chapter 16, “If the Shoe Fits, Write It.”)

SN SPELL NUMBERS from 1–11, as in “one” to “eleven.” So it’s “two million dollars,” not “2 million dollars.”

SP SPELL IT RIGHT If you don’t, it could end up misspelled on the bottom of a TV screen.

SW SIMPLE WORDS are better than longer more complicated words. It’s not an “automobile,” it’s a “car.”

T TRASH In other words, you just don’t need this. It’s extra words, extra time, makes everything harder for the audience to absorb. Shorter and simpler is better.

TS TRIPLE SPACE so you leave room for manual corrections. Yours or mine.

TW TOO WORDY because you gave too much information (TMI). Remember, it goes by your audience only once.

UO UNORIGINAL which means you just lifted words or whole phrases from your source. Come up with your own way of writing something. Depend on source material only for information.

W WRITE THE WAY YOU TALK One of the several times you proofread a piece, listen to how your script sounds. Ask yourself, is this the way I’d tell the story to a friend? If not, rewrite it.

Exercises to Correct Any Lingering Incorrectness___________

1. Rock Starr Returns

If you didn’t see this one coming, you weren’t thinking! The first time you corrected the Rock Starr story, it was with the benefit of earlier chapters but nothing else. The second time, you had the added benefit of alerts in this chapter to flaws that you might have missed the first time.

Now you know something else: how to properly make your corrections when required to do so. Making your corrections tests your proofreading skills as well as your use of corrective markings. This time, you should end up with something anyone could read, sight unseen, in a live broadcast.

Today sinker Rock Starr died at 28, and 11 people, 6 males and 5 females, were also killed too today when a US Airforce C5A transport carrying the singing sensation and the others tragically crashed today in NY’s Long Island Sound. The plane, based at Lake Champlain Ill., had been flying at 43,000 ft. at the time, carrying the volunteer workers and supplies to an air base in Leningrad where a dam building project is underway with US help. Analysts conclude that altitude is a dangerous one is a dangerous one to fly at. The spokesman for the AF, Chris Goldstein, estimates that the loss to the govt from this mishap is estimated at $29,037,292. “We pride ourselves for our air skills, and we’re flat-out shocked by the crash,” the Air Force Chief of Staff told reporters at the Pentagon.

2. Same Thing, Different Story

The exercise here is just like the first one, except you haven’t seen this story before. Trust me though, it needs just as much work as the first one.

Today 2 automobiles crashed during the blizzard on I95. According to state patrolman, Bob Worchester, who’s patrol car arrived at the crash site just a few minutes after it happened, “One of the cars was weaving and crossed over the double yellowline; my guess is, 1 of the drivers was dead drunk.” Both were were critical injured. Witnesses who saw it happen claim that the road was slick from the snow. “Anyone could crash in such bad conditions,” said one. One of the vehicles involved in this awful crash was full of consumables from the supermarket, which already was beginning to spoil. The road just north of N.Y. was closed and still is while the wreckage is removed.