Chapter 7

The Education, Part I

Jennifer stood by the easel and said, “Like we talked about before, we’re breaking down the definition of Operational Excellence into two parts. We’ve already talked a little bit about how to see the flow of value. But, to do that, we need to have flow first, don’t we?”

Peyton and I both nodded.

“Glad you agree,” said Jennifer. “So, if you two were going to try to create flow in your offices, what would you do?”

I thought about it for a few moments before saying, “I’m not sure what you mean. It sounds like creating flow will make things better, so I think I’d just go about it in my normal way.”

“What way is that?” asked Jennifer.

“Well, I’d pull my team together in a room, set some goals and objectives, and do some brainstorming,” I began. “After enough time and good ideas, we’d decide on the best ones.”

“I thought you might respond with something like that,” said Jennifer. “Most companies do just what you described, but that’s exactly what we’re not going to do. Setting goals and objectives and brainstorming work great for some things, but not for creating flow in the office and achieving Operational Excellence.”

“Wait a minute,” I replied. “We do a lot of brainstorming at my company. We always want everyone’s input and knowledge. It’s part of our culture to solicit everyone’s ideas.”

Jennifer didn’t budge. “Yes,” she said. “That’s the common approach, and it’s one of the major game changers in Operational Excellence.”

“All right,” I conceded. “If brainstorming is out, then what do we do?”

“I’m glad you asked,” said Jennifer. “For the rest of the morning, I’m going to briefly describe the sequence of steps we applied to create flow in our office. Peyton, you’ll get more in-depth training on this in the days to come, but for now, I just want both of you to be aware of the process we used. After we understand these steps, we’ll go out into the office and observe them in action. I’ll point out the areas that were transformed and give the associates a chance to explain how everything works and to answer any questions you may have. The exercise will benefit everyone because when the associates explain what they do, they’ll be reinforcing their understanding of Operational Excellence and building confidence in the new system. Let’s get started.”

With that, Jennifer went to the front of the room and stood by the easel. She picked up a marker and flipped to a new page.

“We use nine guidelines to create flow in our business processes,” said Jennifer. “I’ll list them all, and so should you. I’ve found that writing things down helps people retain what they’re learning.”

She listed the nine guidelines on the page (Figure 7.1). “Like I said before, we’re leaving out some steps that you must—I repeat—must go through if you’re going to strive for Operational Excellence,” said Jennifer. “But I won’t go into them now because we don’t have enough time. Plus, today we’re just trying to get an understanding of the process and methodology involved.

“Have you written down the guidelines? These represent a disciplined, scientific, sequential approach to creating flow. We use the first six to design our flow, and we use the last three guidelines to determine how we’re going to operate it. These guidelines are to be used in sequence, not as a menu. We can’t just pick and choose which ones to use, and we don’t brainstorm. This will make more sense as I explain each guideline and show how they build on one another to create flow.”

Takt and Takt Capability

“Takt and takt capability are going to tell us how often we need to process and complete work in the office. First, though, we need to figure out what the demand profile looks like for a particular product or service delivered by the office.”

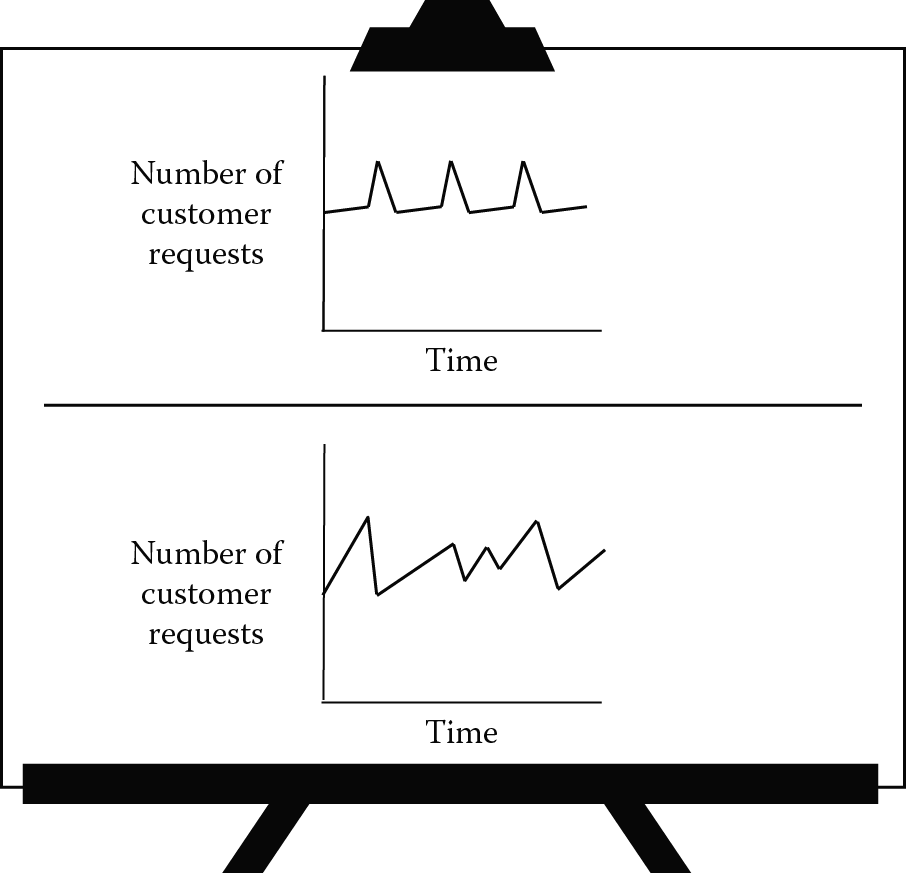

Jennifer drew some quick sketches on the flip chart (Figure 7.2). “The demand profile could look like one of these sketches, it could look fairly steady state, or it could look nothing like these. Either way, we need to determine what the demand profile looks like and identify if there is any variation. If there is, we need to look at what’s causing it.

“For example, with industrial claims processing, we did some analysis and found that the greatest demand was always on Friday. Essentially, our demand profile looked like the one I drew in the upper portion of the flip chart. After some digging, we determined that this variation was self-induced. Some people were just waiting until the end of the week to flush their work to us. So, with a little education and communication, we were able to eliminate some of that variation. Now, we didn’t remove all of it because some was truly out of our control, but this went a long way toward smoothing out the peaks and valleys.

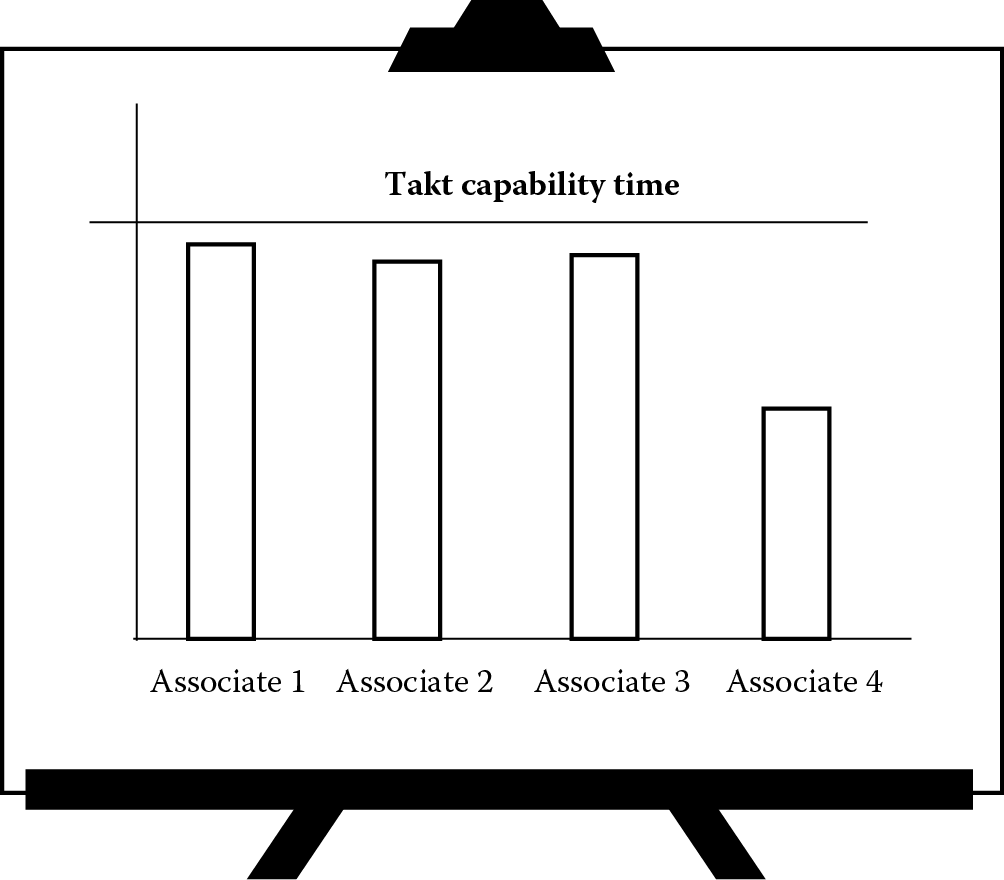

“Once we have a demand profile for the service, the next step is to create a takt capability for it. This is a measurement of how much volume and mix we can produce over a given time period, not just volume like we might see with traditional capacity models. The mix is the critical addition here, and it refers to the different types of jobs we might receive from the customer. In our case, it’s different types of claims. We know that certain claims take longer than others, so if the mix of claims changes, then it’s going to affect how much work we can do within a given time period.”

“But I don’t see how this really helps us,” I said. “Even if we’re able to determine a takt capability, we won’t know exactly what our customers are going to request from us on any given day.”

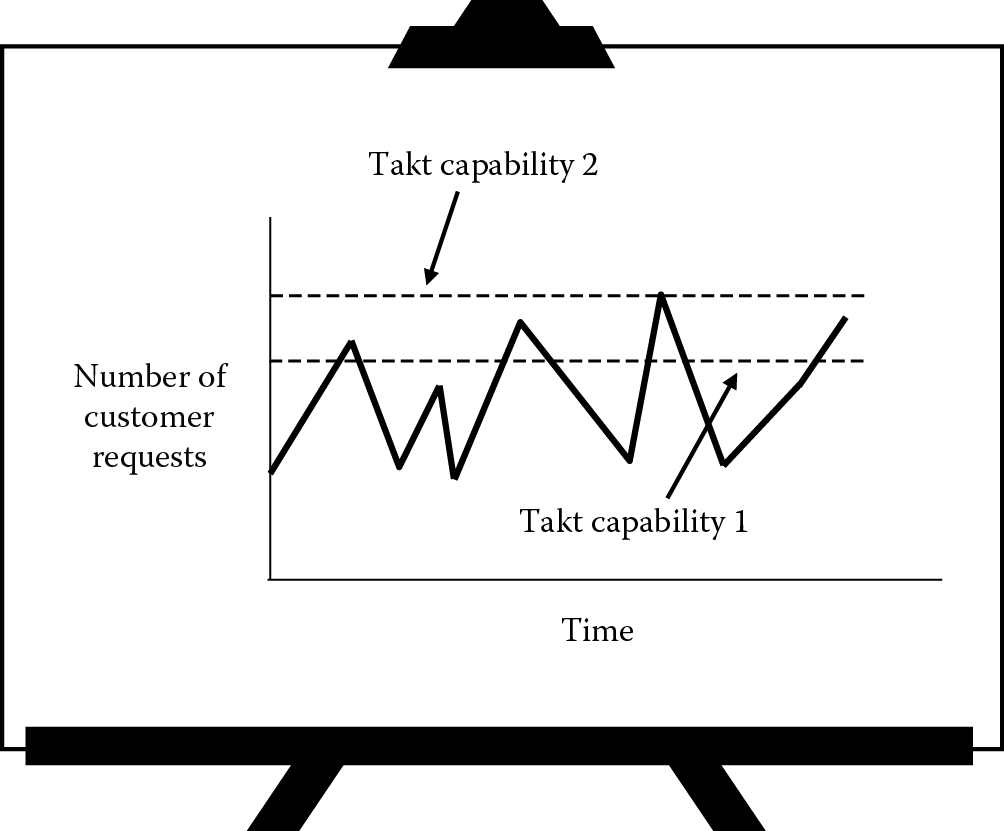

“That’s an important point, Pat,” said Jennifer. “Because we won’t know exactly how many requests we’re going to receive from our customers on any given day, we want to establish not just one takt capability, but multiple takt capabilities. Each takt capability accommodates a specific range of volume and mix we might receive. We might not know what the customer is going to send to us each day, but we should be able to determine the volume and mix we’re capable of completing each day. It would look something like this.” Jennifer flipped to a new page and sketched a new drawing (Figure 7.3).

“The first takt capability needs to be able to satisfy 80% of normal conditions, but we’ll probably need one for peak demand times and maybe even another one for times when demand is way down to make sure we don’t have too many people working on things that aren’t very urgent.”

“OK, that makes sense,” said Peyton. “I wouldn’t think we could have a one-size-fits-all approach.”

“No, probably not,” said Jennifer. “Once we determine the takt capabilities we’re going to use, we then need to determine a takt time for each capability. This will tell us how fast work needs to be completed to ensure we meet the established takt capability.”

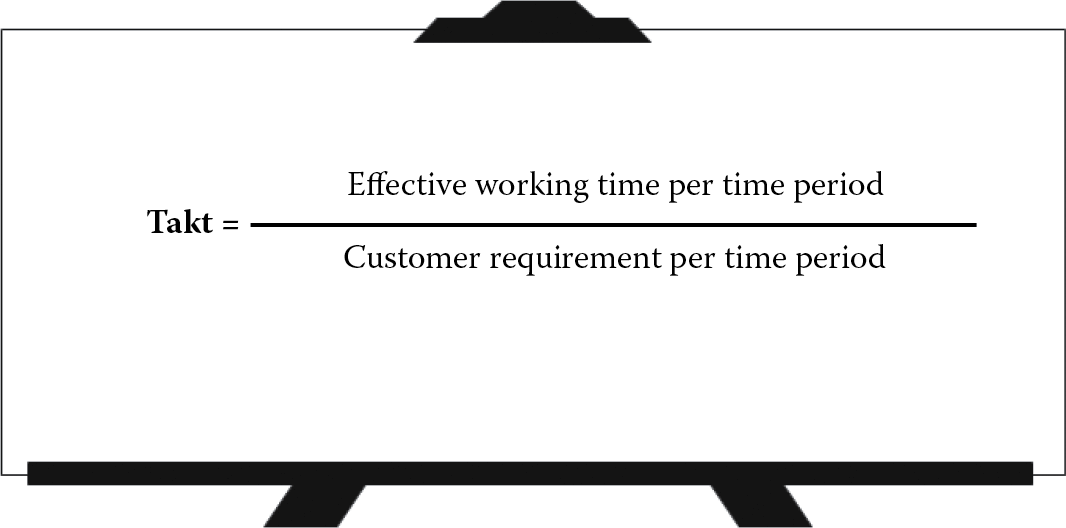

“Do we calculate takt in this case like we would in every other?” I asked.

“Yes,” said Jennifer. “I think you’re referring to what I’m thinking of, but it can get a little tricky in the office, so let me sketch it on the flip chart just to make sure” (Figure 7.4). “Here’s how we compute our takt time,” said Jennifer, pointing to the flip chart. “Peyton, how many effective working hours do we have in a day?”

“Theoretically, we’re in the building 9 hours per day, but many people are here for much longer,” replied Peyton.

“Right, but how many of those scheduled hours do you actually spend working on specific jobs like claims?”

“Well, based on what we just covered, it would depend on the takt capability we set, wouldn’t it?” asked Peyton.

“That’s right,” said Jennifer. “Pat, this is what I meant earlier when I said this could get a bit tricky in the office. The equation for determining takt time still works, but the available time is going to be dictated by the takt capability we’re using. So, we might not have a full day to work on claims. Maybe it’s only 2 hours a day or 4 hours a day, and this will affect how we create a takt time for each takt capability because the available time isn’t quite so set in stone. Does this make sense?”

“I think so,” I said. “As long as we’re following the right process for setting up takt capabilities, I think we’ll stay out of trouble.”

“Yes,” said Jennifer. “And be sure to review the takt capabilities periodically to determine if they need to be recalculated so you’re not caught flat-footed if the demand profile starts looking different.

“This afternoon, on the tour, you’ll see a system that shows our associates when their volume and mix of work has exceeded their takt capability, and you’ll also see how they react and fix the flow before it breaks down—all without management intervention. That brings us back to Operational Excellence, but we’ll save that for when we get to the second part of the definition.

“If there aren’t any other questions, then let’s move on to the next guideline.”

Continuous Flow

“The next guideline is continuous flow,” said Jennifer. “We won’t be able to cover all the details of this one today, but there are plenty of books out there that can help fill in the gaps for you. We saw continuous flow once before during our signature exercise when we demonstrated how to see the flow of value. Because most people in the office are shared resources and divide their time among many different duties and responsibilities, full-time continuous flow isn’t really a viable option. But, we can have part-time continuous flow, where the associates involved all have the same amount of work to do, perform to a takt time, and operate in process one, move one fashion.

“Let’s think back to the exercise we did. What’s it like in our offices now, when we don’t have continuous flow?”

“Work piles up everywhere,” I said. “And not just at the end of the line like it did in the signature exercise. All those in-baskets on everyone’s desks or e-mail inboxes are filled to the brim with work that needs to get done.”

“Good,” replied Jennifer. “What happens to the work while it sits in between everyone? Just to be clear, even though the in-baskets sit on people’s desks, no single associate has ownership of the work in them. The work is in limbo. At that point, it doesn’t belong to the person who put it there any more or less than it does to the person who will eventually take it. So, let me ask you this: What happens or can happen to work while it’s waiting to be processed?”

“Well, it can be sorted and shuffled,” I offered. “Priorities might change. Sometimes, the work requires a more in-depth review because it’s gone cold sitting for so long. Or, a customer’s needs have changed, and we don’t know it.”

“All good responses, Pat, but I’ll answer my own question to drive home the point,” said Jennifer. “What can happen to work while it sits in an in-basket or e-mail inbox? Only two things can happen: anything and everything. This uncontrolled flow is subject to everything you mentioned and more. I think we’d all agree it does us no good for work to sit around waiting like this. Going forward, we’re going to try to prevent this from happening, and continuous flow is how we’re going to do it.”

“OK,” I said. “But how are we supposed to do this without getting rid of individual in-baskets or e-mail inboxes and combining them all? Not to mention, because each associate is a shared resource whose activities take different amounts of time to complete, they’d all be waiting around for one another to finish their work. Surely, we don’t want to do that!”

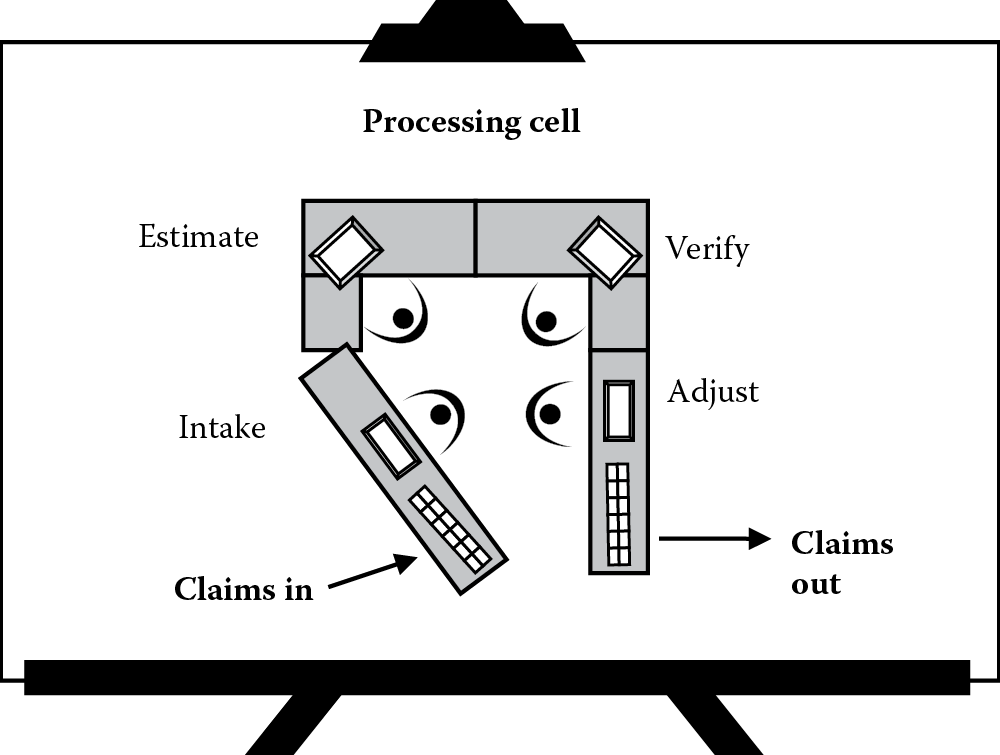

“Let me reply to your two concerns,” said Jennifer. “One is shared resources, and the other is different or varying task times. First, regarding shared resources, because people work on many different things throughout the day, full-time continuous flow usually isn’t an option, so we use part-time continuous flow instead. We can colocate associates for regularly scheduled periods of time, during which we have them operate in continuous flow or process one, move one fashion. We call this group a processing cell, and we set it up to complete work based on an established takt time. When the processing cell meets, there are no priority changes or interruptions, and the work never waits.” She went to the easel and drew a diagram of the idea (Figure 7.5).

An example of a processing cell, where four employees complete work in a process one, move one fashion.

I nodded to Jennifer and gave her a look of partial satisfaction. I understood the part-time colocation idea, but I still doubted that Jennifer could get all the associates in the cell to do their work in the same amount of time.

“For this part-time cell to function properly, it needs to have all the equipment, tools, files, reference books, materials, and network access required to process the work, and we need to make sure everyone’s work takes roughly the same amount of time to complete and is as close to the established takt time as possible,” said Jennifer. “We don’t want anyone in the cell waiting to receive work from the previous person or activity.

“Let me introduce another term called work elements. A work element is defined as the smallest, discrete increment of required work that can be moved to and completed by another person. They’re logical breaking points in the sequence of tasks we do that make up the work as we know it: thinking, composing, editing, calculating, filing, communicating, documenting, retrieving, saving, and so on. We take everyone’s discrete tasks that make up the total process, disassociate those tasks from specific individuals, and then redistribute them in sequence so each associate’s total work takes slightly less time than the takt time established for the takt capability.

“So, we give the first associate in our processing cell enough work elements, in the correct sequence, of course, so that he or she produces at slightly less than the established takt time. We then take the remaining work elements and continue to redistribute them in sequence to the next associate in the processing cell until he or she also produces at slightly less than the established takt time. We continue until we’re out of work elements.” Jennifer sketched this for us on the flip chart (Figure 7.6).

Work elements redistributed so each associate completes his/her work under the established takt capability time.

“If the work elements for the last person in the cell fall further below the takt capability time, that’s OK. They could bring in some extra work to help offset the time they would otherwise be idle. For everyone else, we want the work elements to add up to slightly less than the takt capability time, or at least as close as possible.

“I’ve oversimplified things here somewhat, and I recognize that we may bump up against some personal barriers when we do this, but that’s a cultural issue. For right now, though, can you see how the work element concept can be used to redistribute work, create and maintain flow, and avoid having people sit around and wait?”

“You’ve certainly made a good argument for part-time continuous flow, and addressed the issues I had,” I said. “But, I’ll have to think about the specifics some more. In the meantime, what do you do with a work element that’s tied to a person with a unique skill?”

“Good question, Pat, and it tells me you’re considering how you might apply this idea at your company,” replied Jennifer. “When we go to implementation, we may need to do some cross-training if someone’s skill set or knowledge prevents us from achieving continuous flow. Often, we need to consider which work elements are core work and which ones are noncore work. Core work can’t be moved to someone else because it requires specialized training, whereas noncore work can be shifted around with a little training or education. For example, an engineer probably can’t do an accountant’s job, and vice versa, but they both could probably be trained to fill out header information for the other person.

“This might limit our ability to colocate people in part-time processing cells, but we’ll still see benefits from bringing everyone together and eliminating wait times for the work. If someone’s processing time is lower than everyone else’s and there’s nothing we can do about it, then they could bring other work to complete while they are idle, but the work being completed in the processing cell would need to be given priority all the time.”

“It seems like the work elements can be reassigned to accommodate various takt times, but what happens when we actually find ourselves in a different takt capability?” asked Peyton. “It seems like a lot of work to reassign all those work elements every time the takt capability changes.”

“Another great observation,” said Jennifer. “We’ll be talking about something called standard work in guideline number six, which will help us capture and define how we distribute the work elements for each takt capability. When the takt capability changes, the associates might meet more often, work longer hours, or add people to the processing cell. The standard work tells them what to do in each case, without management. The associates will simply reference the different, preestablished distributions in work elements. So, to answer your question, the different work element distributions have already been preestablished before they are ever needed or used.

“There are many options for designing your processing cell to meet different takt times. I won’t get into the details now—I’ll leave those for the reference books*—but it’s possible to figure out how many associates you need for each takt capability and the amount of time for which they’re needed.”

“But none of this is really new,” I said. “I saw something like this at my old company. One of the departments had a study hall period, during which a group of associates would meet each day for a specific, uninterrupted period of time to complete their routine assignments. I’m not sure they took it to the level of takt capability or work element distribution, but the group had a good performance record.”

“Well, I certainly don’t know what happened at your old company, so I can’t say what they did or didn’t do,” said Jennifer. “But based on my experience, I know that some companies do a great job creating isolated processing cells, or something we might call pockets of flow, very similar to what we just discussed. What they usually don’t do, however, is connect these isolated cells to all the other activities that have to take place in the office to complete the work, and the work just piles up and waits somewhere else even longer than it did before because nothing is connected. This is a great segue into our next guideline.”

FIFO (First in, First out)

Jennifer continued on to the next topic without missing a beat. “Now, we may be able to create some part-time processing cells, but we’re going to encounter situations that will prevent us from creating them everywhere, and that’s OK. So, let’s talk about what we can do when that happens.

“If we can’t create processing cells everywhere, we’re going to use a guideline called FIFO, which stands for first in, first out. Most people are familiar with this term from its use in accounting. For our purposes, though, we want to think of FIFO as a form of flow used to regulate the sequence and volume of work between two disconnected processes. This could be connecting a processing cell to the next activity or just connecting two activities, neither of which are processing cells.

“Let’s do an exercise to help us understand how FIFO works. Say we introduce blue, green, yellow, and red ping-pong balls into the top end of a pipe. In what order do you think the balls would come out the other end of the pipe?”

“In the same order they went in,” replied Peyton. “Blue, green, yellow, and red. That’s a no-brainer.”

“Good,” said Jennifer. “Now, let’s imagine that Pat is loading the pipe with a certain color ping-pong ball, and Peyton is unloading a ball from the pipe at a regular time interval. Pat, you have a large supply of colored ping-pong balls, but let’s say the pipe is only long enough to hold five at a time. What’s the lowest and highest number of ping-pong balls that could be in the pipe at any given time?”

“Zero and five,” replied Peyton.

“Right again,” said Jennifer. “Do you see how the length of the pipe controlled the amount of ping-pong balls that could go into it? It’s very different from an in-basket or email inbox, where files stack up higher than the sides and any number of jobs might be present. In our exercise, Peyton, you were removing individual ping-pong balls from the pipe, but how did you decide which ping-pong ball to take when you were ready for the next one?”

Peyton seemed a bit puzzled. “I’m not sure what you’re getting at. I wouldn’t really have any choice. I would just take whichever ping-pong ball is next in line in the pipe. It’s not like I could pull some out until I found a favorite color and then reload the extras back into the pipe, could I?”

“Perhaps the question was ambiguous, but I like your answer,” said Jennifer. “You’re right; you would simply withdraw the next one from the pipe.”

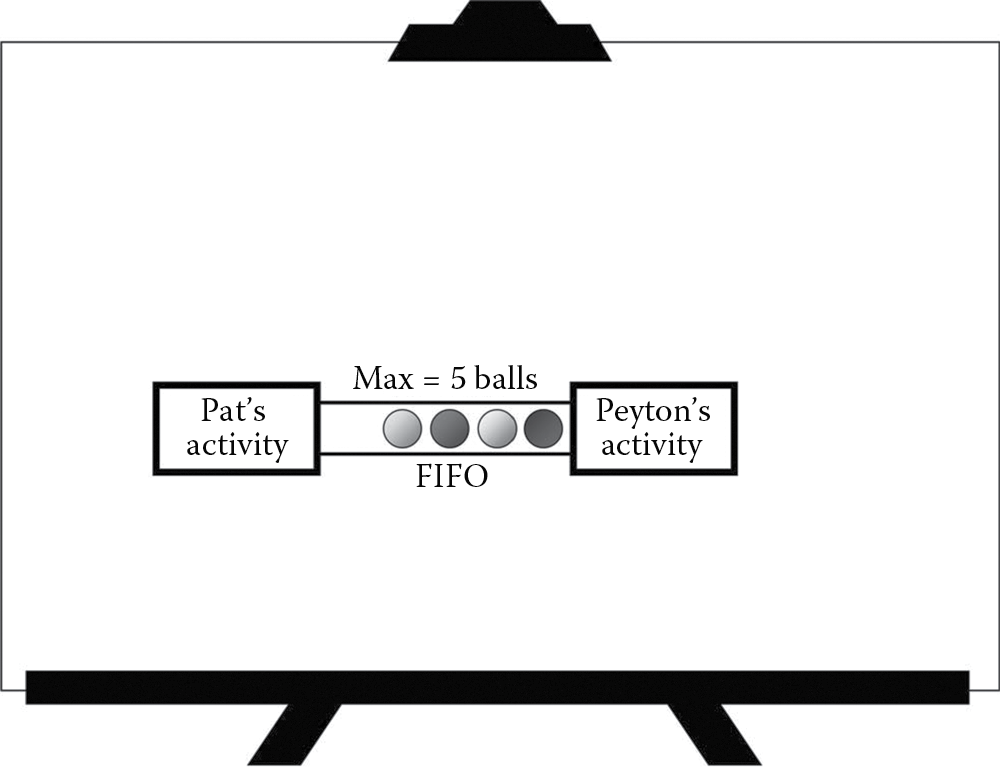

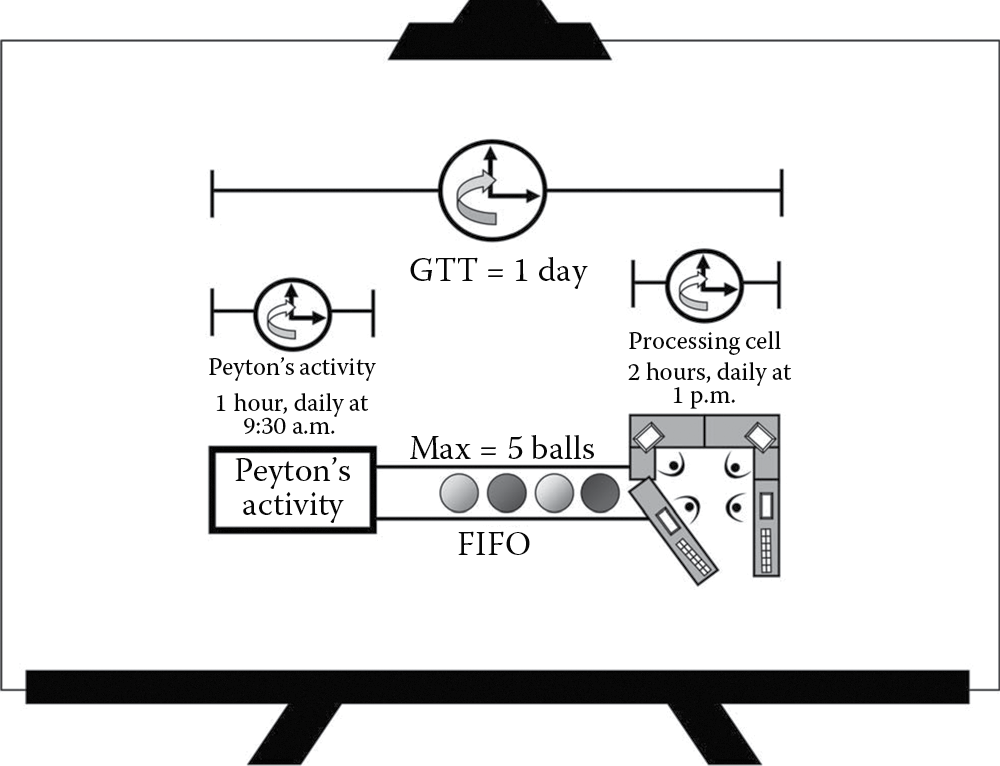

She then went to the flip chart and constructed a diagram of two activities named Pat and Peyton and connected them with two parallel lines. Underneath the lines, she wrote “FIFO,” and on top of them, she wrote “Max = 5 Balls.” Then, she added balls of various colors (Figure 7.7).

“This diagram represents how we would connect two processes together using a FIFO lane,” she said. “You’ll see something like this when we take our tour this afternoon, but with jobs and work, not balls.”

She finished the drawing and turned back to us. “When the FIFO lane fills up, what happens to each of your activities?”

“Well, I wouldn’t be able to put any more balls into the pipe,” I said. “I’d have nothing to do.”

“If you’re a shared resource, you’d likely do something else for a while until an empty spot opens up in the FIFO lane,” replied Jennifer. “You’re correct, however, in assuming that if you continue to process work meant for Peyton’s process, it would have nowhere to go. That would be a problem.

“If you can somehow help Peyton to get back on track, then that’s great, but often this just isn’t possible. A junior accountant might not be able to help the finance manager he’s sending work to, but he could work on something else until space in the FIFO lane opens up again. This can get tricky, though. In the office, we would not want the process feeding the FIFO lane to stop sending its work. So, we would create an overflow FIFO lane, but as soon as it’s used, it would be a signal to everyone that we’re in an abnormal flow condition, and this would mean that some additional response is required.

“What about for you, Peyton? What would you do if the FIFO lane backs up?”

“I don’t see any difference for me,” said Peyton. “I would just keep doing what I normally do, but I imagine I’d be able to see when the FIFO lane becomes full, right?”

“That’s right,” said Jennifer. “We’ll talk more about what we do in that situation when we get to the second part of our definition of Operational Excellence about fixing flow before it breaks down, although some of what I just mentioned will apply.”

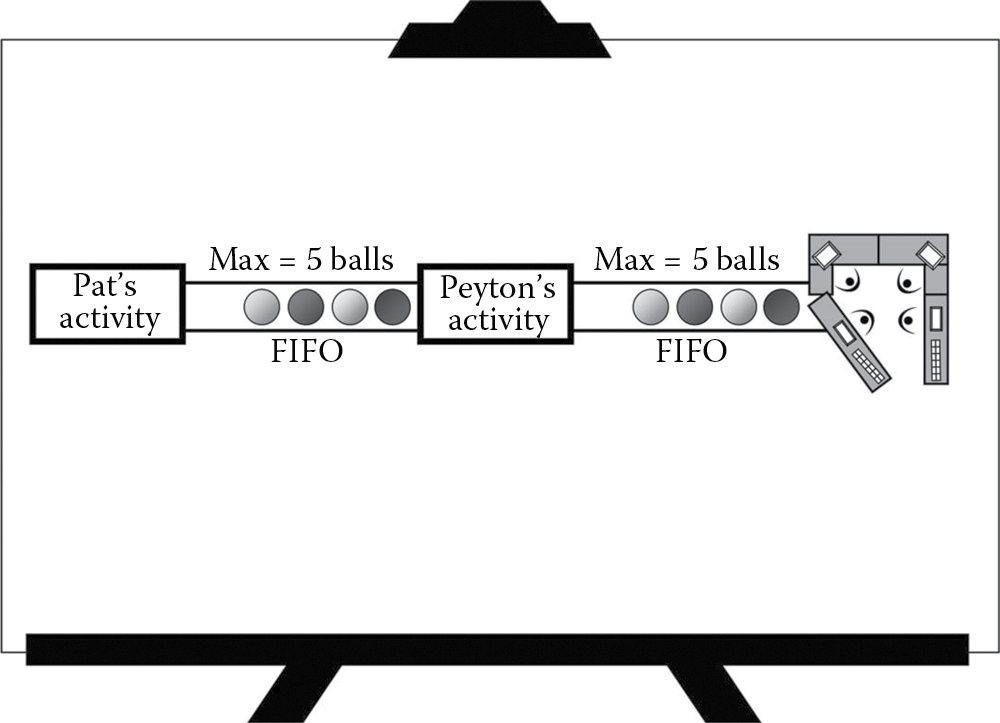

She turned back to the diagram and added another FIFO lane off to Peyton’s right and connected it to a processing cell. It was clear from the example that the processing cell would always know what to work on next from the FIFO lane that fed it (Figure 7.8).

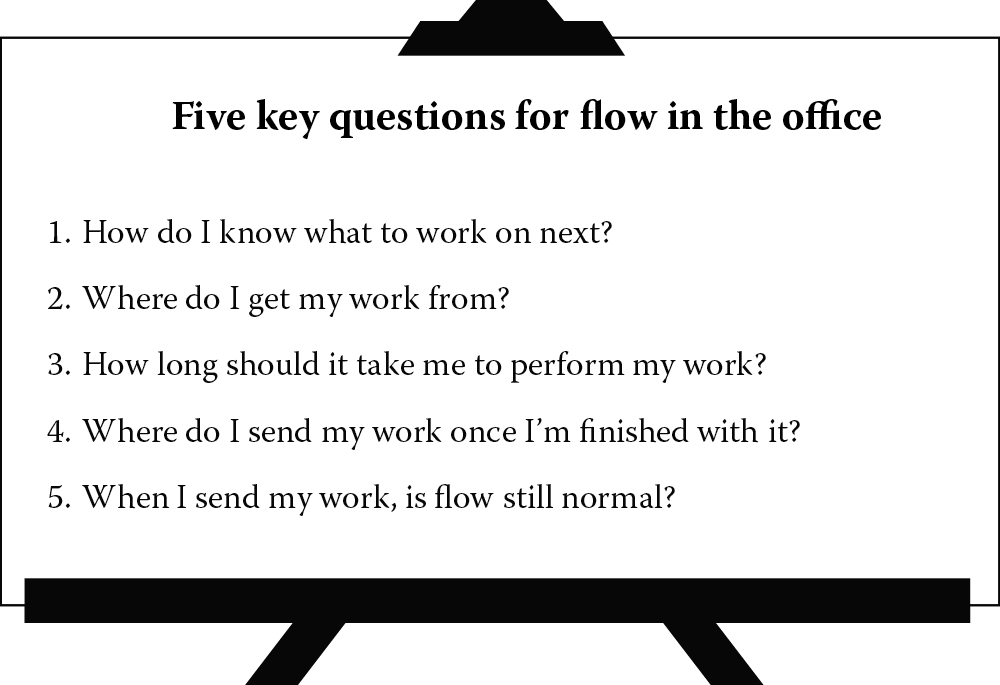

“For the moment, I want you to recall the five questions we asked previously to determine if we had flow,” said Jennifer. “Peyton, do you want to try answering them again, this time using this example? Let’s say it takes you 20 minutes to ‘process’ a ball from the FIFO lane once you withdraw it.”

“OK,” said Peyton. “I’ll give it a try. The first question is, how do I know what to work on next? That’s easy. I just take whatever is in the FIFO lane. The second question is, where do I get my work from? That one’s simple, too. I get it from the FIFO lane, and I’m sure in a real one, there would be a specific spot from which I would retrieve my work or maybe even a specific folder in my e-mail inbox. The third question is, how long should it take to perform my work? You said 20 minutes, so that’s how I know.

“The fourth question is, where do I send my work once I’m finished with it? I would put it in the FIFO lane that feeds the processing cell. Again, in a real-life setting, I’m sure there would be a specific spot in which I’d put completed work or maybe even a specific e-mail title to use so it could be funneled to a specific folder in someone else’s e-mail inbox. The fifth question is, when I send my work, is flow still normal? The FIFO lane going to the processing cell determines this one. If there is an open space, then I know flow is normal. If the space isn’t open, we have abnormal flow, and everyone would know an additional response is required.”

“Nicely done,” said Jennifer. “There might even be situations where we need to use multiple FIFO lanes if more than one type of work is flowing into the same processing cell. If we have multiple FIFO lanes, we need to have an indicator that tells us which FIFO lane to pull from next. The indicator could be an arrow or a sign that says ‘Next Job’ or ‘Complete This Next.’ No matter how many FIFO lanes we have, we should always be able to answer the five questions for flow for each one.”

“That’s why FIFO is considered a form of flow, isn’t it?” I asked. “Because we’re able to answer those five questions?”

“Exactly,” said Jennifer. “Continuous flow and FIFO tell us how the work will flow, but what about when the work will flow? That brings us to the next guideline.”

Workflow Cycles

“A workflow cycle refers to the rate at which work moves or flows within or between different work areas or departments along a fixed pathway,” said Jennifer. “This guideline builds on what we already established with our other ones, and it adds structure and discipline to them, too.

“Workflow cycles help us stabilize and regulate flow in the office, and they enable everyone to know the time at which they’re going to receive their work. It’s not an expediting system, but rather an indicator that tells us when work is going to flow along preset pathways and when knowledge will be captured. To ensure consistent, predictable results, workflow cycles should occur at preset time intervals.”

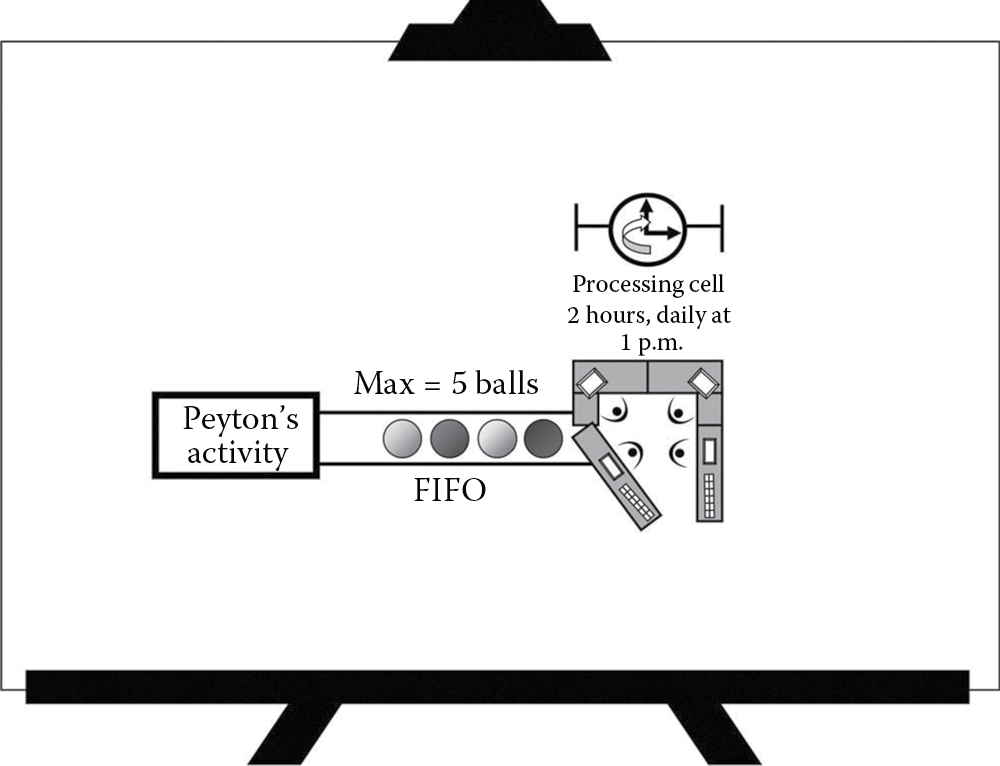

Jennifer walked back to the easel, then turned around. “Let me give you a specific example,” she said. “In our FIFO exercise, let’s look at just Peyton’s activity and the processing cell now. We would define a workflow cycle that describes the time at which the cell will process work and for how long it needs to process work. We might design it so the cell processes work every day for 2 hours, beginning at 1 o’clock.” Jennifer drew on the flip chart, adding more information to a portion of the previous FIFO example (Figure 7.9).

“We want to create a workflow cycle at this level whether we’re dealing with an activity done by only one associate or a processing cell staffed with multiple associates. Somewhere in the area, we want to indicate to everyone that the associates in the cell have essentially promised to process everything in the FIFO lane by a certain time each day.”

“So, this helps the associates know when to expect output from a particular activity or processing cell?” I asked.

“Yes,” said Jennifer. “Because work flows at the processing cell at a preset time and along a preset pathway, everyone knows when they should expect to get their work from it, but that’s not all. There are different levels of workflow cycles, too. The concept applies between multiple activities and processing cells from the start of the flow to the end. If everything in the office operates to a workflow cycle, then we’re able to establish a guaranteed turnaround time for the entire office. This means that the time by which work will be completed is repeatable, predictable, and known in advance by everyone in the company.”

She added even more detail to the example (Figure 7.10). “We can do this because we know how long it takes for work to be completed at each individual step, and we also know when work will be passed along to the next activity through the FIFO lane. If we know these two elements at every step in our office, then we know the guaranteed turnaround time for the entire office. Think of the advantage you would have over your competitors if you could provide guaranteed turnaround times to your customers.”

A workflow cycle created for the first process and another, overarching workflow cycle created for the entire end-to-end flow, which establishes a guaranteed turnaround time (GTT) for that flow.

“It makes sense,” said Peyton. “No wonder this system is being introduced to other areas here. It not only creates flow, but also establishes guaranteed turnaround times for our work that we can share internally and with our clients.”

“You got it,” said Jennifer. “Having workflow cycles eliminates the need for countless voice mails and e-mails because people know when they’ll receive their information. Each area in the office knows when a claim will be finished, so they don’t need to check on it.”

“The workflow cycle concept isn’t as confusing as I first thought,” I said. “But, what about if we have office processes that don’t happen very often, like closing out the books for a quarter?”

“Great question,” said Jennifer. “In that case, we would use something called an integration event, which is the fifth guideline.”

Integration Events

“Integration events† are a formal handoff of information between different areas of the office,” said Jennifer. “They pull large amounts of information forward from one area to another by matching the output of the parties providing the information with the inputs required by the party receiving the information to ensure information flows and knowledge is captured.”

“So, we might use an integration event to close out the books, like Pat mentioned,” said Peyton.

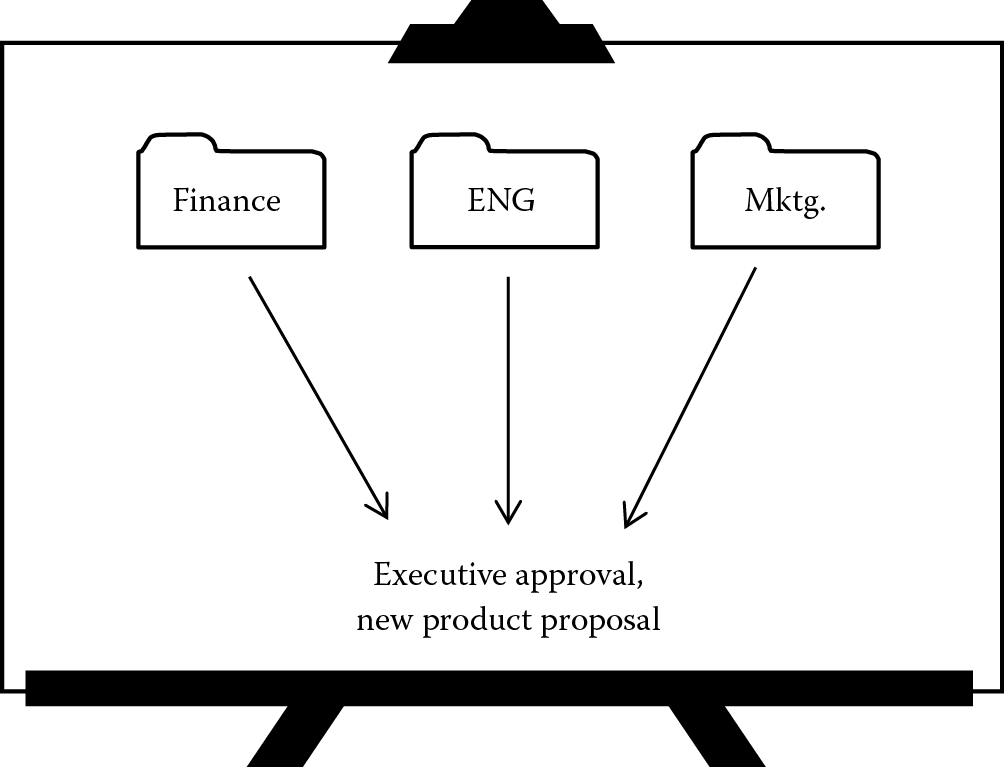

“Yes,” said Jennifer. “Another example could be turning over a project for executive approval. The vice president receiving the project package would need to be given all the information required to sign off on it, without having to go back and track down anything missing. The departments providing the information would make sure that their output matches with the inputs required by the vice president.” She drew a quick picture on the flip chart (Figure 7.11).

During the integration event, each department (Finance, Engineering, and Marketing) provides the outputs necessary to match the inputs that are needed by the executive in order to create a new product proposal.

“That seems to happen every now and then where I am,” said Pat. “The information gets where it needs to go eventually, but not without a good amount of rework and arm twisting; sometimes, it can get even worse.”

“You’ve actually hit on one of the key elements of integration events,” said Jennifer. “They are strictly the transfer of large amounts of information from one area of the business to another. It’s not a milestone meeting. There’s no bargaining, cajoling, negotiating, or asking questions, and no decisions should be made. All the information that’s needed is provided in the format in which it’s needed. This way, the person receiving the work can do what they need to do with it without any additional processing.”

“That sounds like it would be a good way to determine if one department hasn’t been able to keep up,” I said. “If everyone is supposed to deliver their information at one preset time, then it would be easy to see who hasn’t.”

“That’s true,” said Jennifer. “Integration events shouldn’t be meetings or status checkups, but they would provide visibility into this like you’re saying.”

“So, to make this work, there need to be standardized procedures for the flow, right?”

“I think you’re hinting at standard work, Pat,” said Jennifer. “Let’s talk about that now. It’s the next guideline. We need to develop robust standard work to establish regularity and consistency in our activities, part-time processing cells, and FIFO lanes. When we do, we’ll hit our workflow cycles and guaranteed turnaround times every time.”

Standard Work

“The sixth guideline is critical to the successful operation of our office,” said Jennifer. “Standard work means establishing the one best way to do a job or task and then ensuring everyone uses that method so that the work required is performed the same way and in a consistent amount of time, every time. Standard work helps us create a disciplined plan that all associates can follow, and we won’t just have standard work for how we do things in the office. We’ll also have standard work for the flow.

“In our office, we need to develop standard work for the flow of knowledge and information, and flow cannot exist without stability and repeatability in the things we do. Processing cells, FIFO, and workflow cycles provide the pathway and timing for flow, and standard work helps make the pathways and connections robust and keeps work moving along the connections we set up.

“It’s not always easy to create or sustain standard work in the office, though. Education and leadership are critical, and so is a destination so people understand exactly what standard work should look like once it’s achieved. Management needs to prepare the organization first and then drive the process and methodology for creating standard work.

“Is there a go-to person in your office who knows how to get things done? In most organizations, a lot of activities happen only because of the longevity of the workforce, or something we call tribal knowledge. Different individuals informally create work standards that they use to complete their work correctly. But, the details generally aren’t documented, and the knowledge resides only with a few people, which means it has the potential to be discarded when people take vacation, are relocated, or retire.

“Standard work captures the best practices and lessons learned from each associate. Having the work defined and documented makes training more effective for new or temporary employees. A consistent approach and methodology also minimize the chance of introducing noise or chaos into the system. Things are done correctly, consistently, and with less variation from person to person because everyone uses the same method. In essence, standard work leads to better quality, lower cost, and improved morale.”

I got the feeling Jennifer had lots of experience discussing this topic, as she seemed to speak with authority, wisdom, and as someone who had fought this battle many times before.

“People generally learn in three different ways,” she said. “By hearing, seeing, and doing. We retain less than 5% of the information we hear when we’re learning something new. When we see it, we retain about 60%. But, when we learn by doing, we retain approximately 90% of the information because we trust what we do. Standard work makes use of the best methods of learning by allowing associates to participate in the learning. They hear it explained, watch the process, and then perform the task using standard work to guide them. What method have we been using this morning?”

“Mostly hearing,” said Peyton. “There’s been a little watching, because of your drawings, and some doing with the exercises, so I guess we can’t be expected to remember much by tomorrow.”

That frightened me. I had heard a lot of good stuff so far, and to think I might not be able to put it all together for Chris was disturbing.

“That’s right, and that’s why we’re rushing through this morning,” said Jennifer. “Before the memories fade, I want you to take the tour and see what you’ve heard. Peyton, you’ll have the opportunity to actually do all of this in the near future. Pat, I hope the 60% retention rate will work for you if you lean on your experience.

“All right, back to standard work. Once we develop standard work, we should always use it because it represents the best method for how to do things. If you stop and think about it, why would we ever use anything else? Once we create standard work, we need to recognize that it can be improved at any time. However, it’s difficult to improve results if we only rely on one person or a select few, especially if one of them is the boss. If you’re looking for ways to improve existing standard work, make sure you involve everyone.”

Shifting gears, Jennifer suggested we jot down the next part.

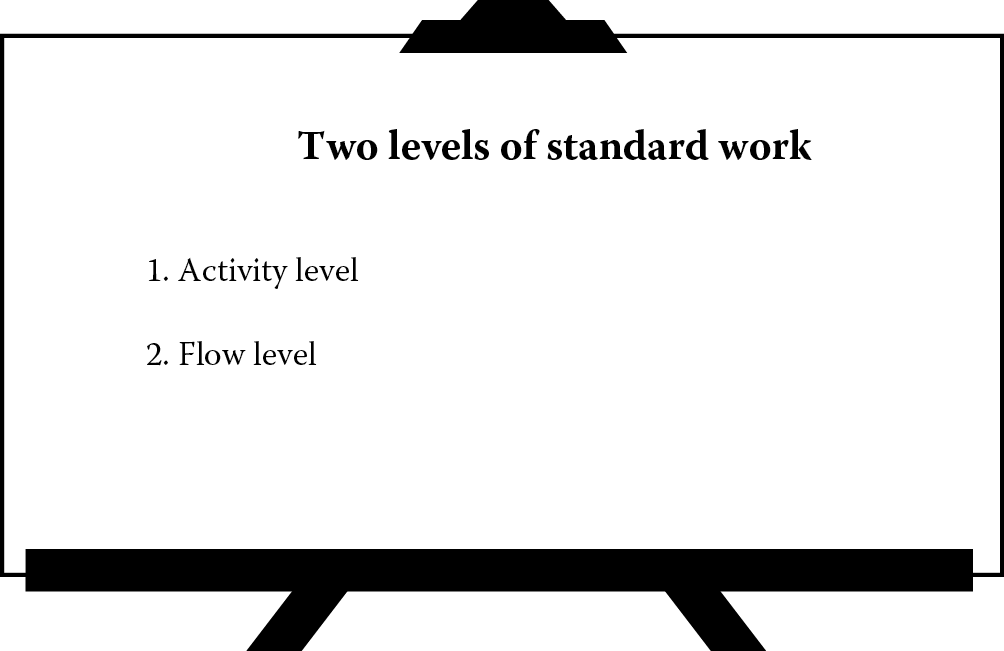

“In Operational Excellence, there are two levels of standard work: activity level and flow level. Be sure to keep the levels separate rather than trying to combine them.” She started on a new page on the flip chart and wrote down the two levels (Figure 7.12). “Both of these represent a level at which we need standard work,” said Jennifer. “I’ll explain each level and what the differences are between them.

“Activity-level standard work occurs at the level of an individual. Here, we want to describe what the job is, who is responsible for doing it—titles, not people’s names—and how long they should work on it. We also want to include the content, tools, systems needed, sequence required for completing the work, and any other necessary information. This makes for a better and more optimized process. Any questions about activity-level standard work?”

I felt an obligation to ask, given the opportunity. “So, activity-level standard work just details what an associate does for the job, things like the file used, the references, the specifics about documenting or creating a claim entry. This is where I might use photos, diagrams, screenshots—stuff like that, right?”

“That’s correct,” replied Jennifer. “It doesn’t need to be complicated. In fact, the simpler the better. Also, remember that whatever you create will likely be improved regularly, so structure your documentation to allow for that and, as a leader, encourage it.

“Let’s look at the flow level next. This is where we connect the activity of one person to the activity of another. This level of standard work answers questions such as, How do I know what to work on next? How and when do I pass work to the next process? What are the connections between activities? These are all flow-level questions, and they involve team activities and multiple people. Any questions here?”

“So, this is where the rules for FIFO and workflow cycles would come into play?” asked Peyton.

“Yes, exactly,” said Jennifer. “Certain parts of flow-level standard work will already be settled by virtue of the rules of FIFO and workflow cycles, but it’s also where our five questions for flow come into play. If we have good flow-level standard work, then we should be able to answer all five questions for each connection in our office.”

Jennifer flipped back to the easel page with the five questions for flow (Figure 7.13). “Flow-level standard work establishes the standard for normal flow between activities,” said Jennifer. “If employees can see normal flow, then they can see abnormal flow, which I’ll talk more about later.”

With the morning slipping away, and apparently much more to cover, Jennifer’s pace picked up noticeably.

“All of the guidelines we’ve covered so far, as well as the ones we haven’t, tie together,” she said. “It’s difficult to separate them when they build on one another in an integrated system. The first six guidelines we covered—takt and takt capability, continuous flow, FIFO, workflow cycles, integration events, and standard work—all make up how we design our flow. The next three guidelines we’re going to cover will describe how we operate it on a day-to-day basis.

“Let’s take a short break and arrange for lunch. We’ll be ordering from the deli in our cafeteria, so here’s a menu for each of you. Just check off what you want, and it’ll be delivered so we can continue our conversation while we eat. Sorry to take that hour away from you, but we’re packing a lot into one day.”

Jennifer collected our forms and handed them to someone who was responsible for making sure our orders got to the right place at the right time. While we waited for our lunches, I reviewed my notes, eager to see what would come next.

From the Author

The first six guidelines constitute the design of flow for the office. Starting with takt and takt capability and working through activity- and flow-level standard work, each guideline builds on the last and creates the operational design for how information will flow and knowledge will be captured in the office.

With the first six guidelines in place, we should be able to answer the five questions for flow at each activity by establishing formal connections between them. These five questions tell us how and when work will be completed at each activity and how and when it will move to the next activity. By following these design guidelines, everyone in the office knows how and when information will flow. All of the e-mails and phone calls that are generated to find information are eliminated, and with this, the office environment becomes more stable.

In addition to bringing stability to the office, the first six guidelines begin to create the ability to distinguish between normal and abnormal flow. Establishing a takt capability, for example, lets everyone know the volume and mix of work that can be processed within a given amount of time. If customer requests exceed either of these established parameters (or both), then everyone immediately knows and understands that the office is in an abnormal condition.

Continuous flow and FIFO help distinguish between normal and abnormal flow also, as both have specific rules that govern their operation. Work is not allowed to pile up between activities in a processing cell, and each FIFO lane has a “max” associated with it. If we find that work is piling up in a processing cell, or that FIFO lanes have exceeded their max, then everyone quickly and easily can see that something has gone wrong.

While continuous flow and FIFO establish normality and abnormality for the quantity of work permitted, workflow cycles do it for the timing. With workflow cycles created at each activity or processing cell in the flow, everyone will know the time by which work should be completed. From this knowledge, the timing of the end-to-end flow can be determined and a guaranteed turnaround time established for all customer requests.

The first six guidelines create a powerful design for flow in the office, and combining them with the final three guidelines sets organizations on the right path to achieve Operational Excellence in their offices.