Chapter 8

The Education, Part II

After the break, Jennifer pulled us together for a quick review before moving on. “Let’s do a recap of the first six guidelines,” she said. “Who wants to tell me what they are?”

“The first guideline is takt and takt capability,” I said. “First, we look at our demand profile and determine how many takt capabilities we need. Then, for each takt capability, we determine a takt time, and this is the rate at which we need to complete work for a service our office provides.”

Peyton jumped in and said, “The second guideline is continuous flow, where we analyze all the activities, colocate associates, balance work elements, and design a part-time processing cell that operates on a process one, move one basis. Because we set up this cell with the ability to flex to different takt capabilities as well as meet at regular, preset times, we always know when information will flow, and we’re able to remove a lot of the waiting that plagues the office.

“The third guideline is first in, first out, or FIFO, which is a form of flow used to regulate the sequence and volume of work between two disconnected or imbalanced activities. FIFO allows us to keep work in sequence between activities if we’re not using continuous flow. It also creates robust connections between activities in the office.”

“The fourth guideline is workflow cycles,” I said. “We use them to establish preset pathways and timing for the flow of information between activities and connections throughout the entire office. With robust workflow cycles, we’re able to flow work through our office at guaranteed turnaround times.

“The fifth guideline is integration events, which are formal handoffs that pull large amounts of information forward from one area of the office to another by matching the outputs of the parties providing the information with the inputs required by the party receiving it. They’re not milestone meetings, and no decisions should be made at them.

“The sixth guideline is standard work, which helps establish regularity and consistency at our activities, continuous flow processing cells, and FIFO lanes. Standard work is applied at the activity level to tell us how a process should function and at the flow level to link different activities and processing cells together. Standard work enables us to consistently hit our workflow cycles and predictably flow work through the office at guaranteed turnaround times.”

“Wow,” said Jennifer. “You both pass with flying colors.”

“So, are we done now?” I asked.

“Not yet,” she said Jennifer. “Remember, the first six guidelines were all about how we design our office for flow. The remaining ones we’re going to cover are about how we operate that flow. Let’s get started on the last three.”

Single-Point Initialization

“Now, we want to address how we initialize work into the flow and maintain a set sequence until the request is delivered to the customer. When an assignment is started in a typical business process, each associate sets his or her own priorities and then pushes completed work to the next step, whether it needs it or not. This approach provides no regularity or predictability to the flow of work in the office, and it causes us to meddle and shift priorities around.

Using the first six guidelines, we’ve designed an office where each activity is linked or connected in flow all the way to the customer.”

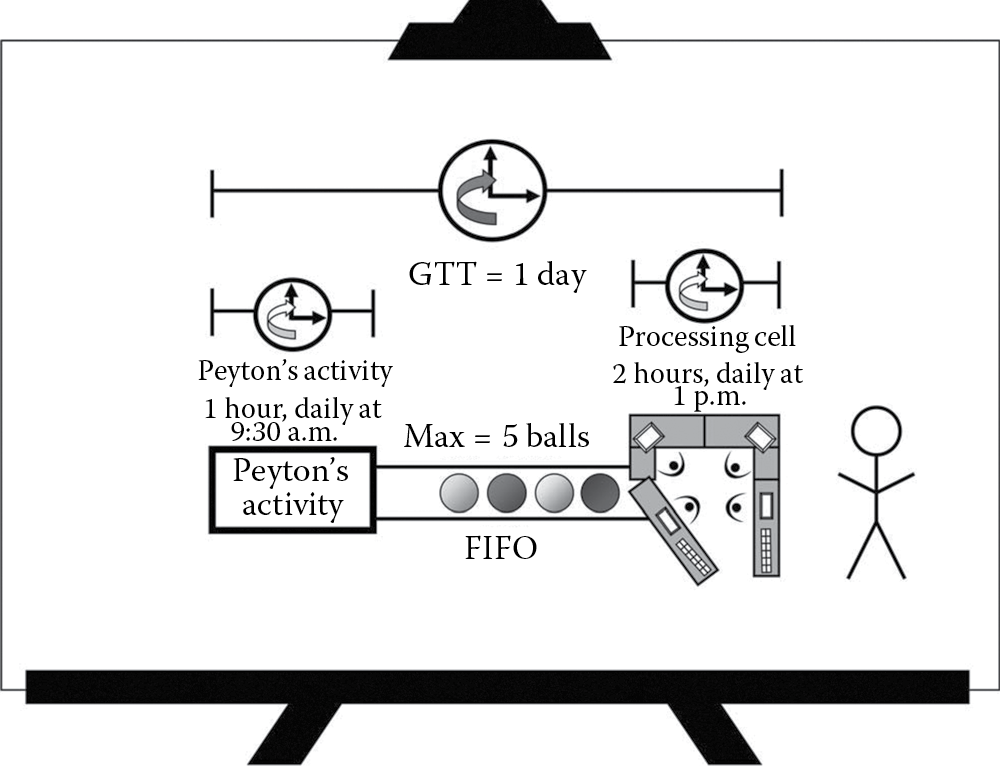

Jennifer walked to the easel and added a person at the end of the diagram she had drawn previously (Figure 8.1). “Here’s our customer, all the way on the right,” she said, pointing at the stick figure. “And on the left are the activities and connections that deliver our work to that customer. But, where and how does the work get started? If it’s possible, we want to have only one place at which we initialize the flow, and we call this the initialization point.

“All of our office flow happens after the point at which we initialize the work. From there, we process in continuous flow or FIFO all the way to the customer. This is an important point because if the sequence of work remains fixed after the initialization point, and if we know how long each step takes, then we can predict the time it’ll take for work to be completed once it’s been released into our system. That’s how we’re able to create and live by those guaranteed turnaround times we’ve been talking about.”

“So, we introduce a job at the initialization point and, after that, we have flow all the way to the customer so the sequence of work remains fixed,” said Peyton.

“Yes,” said Jennifer. “However, it might be necessary to resequence work at fixed points in the flow because of external factors beyond our control. For example, if work has to go to an outside entity halfway through the flow, be reviewed, and then reenter the flow, the reentry point could be a good spot to resequence the work, if it’s necessary. This would be called a sequencing point. These sequencing points need to be well defined if they exist and shouldn’t be based on management priorities but rather external factors.”

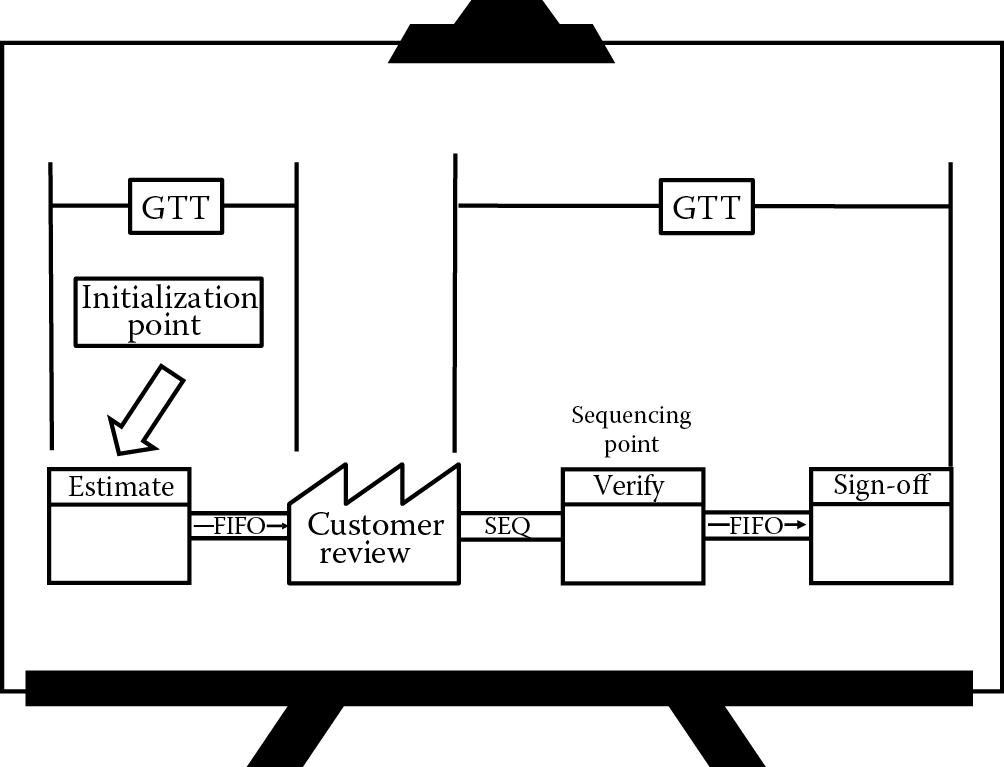

Jennifer turned to a new page on the flip chart and drew another diagram (Figure 8.2). “In this example, the initialization point is the first process. After ‘Estimate,’ work moves in FIFO through the rest of the flow, but once the estimator is finished, work goes out for ‘Customer Review,’ which is outside the office. Because we can’t control when or the order in which the customer will send completed work back to us, the process that receives the work from the customer can be a sequencing point. Remember we use sequencing points only when outside factors beyond our control warrant them, like customers needing to review work midway through the flow, not because of management priorities.

Separate GTTs exist for the segments of flow that occur before and after “Customer Review,” the external factor that causes the need for a sequencing point at “Verify” as work comes back into the office.

“At ‘Verify,’ work can be resequenced as it comes back into the flow from the customer, then this sequence would carry through the rest of the flow. All the work that happens before and after ‘Customer Review’ is within our span of control, so we can create two separate guaranteed turnaround times: one governing everything that happens before the work goes out to the customer and the other governing everything that happens when the work returns from the customer. Note that if we have a sequencing point in the flow, we put ‘SEQ’ in the lane instead of ‘FIFO’ so everyone knows that the process being fed by the lane is a sequencing point.”

“So, the initialization point helps create a guaranteed turnaround time for the entire flow and allows us to predict the time by which we’ll complete the work,” said Peyton. “If there’s an external process involved, like the ‘Customer Review’ step in your diagram, we can create a sequencing point where the work returns to the flow and set guaranteed turnaround times for what we’re able to control before and after the external portion. Just to be clear, you’re talking about the same work that’s in my department right now, all those jobs that have unknown completion dates?”

“Yes,” said Jennifer. “Sound believable?”

“Not really,” I replied. “I admit you’ve constructed a good case for designing flow to improve performance, but you’re telling us that we can launch a job into the office, never change priorities, and be certain of its completion time! I’ve got to see it to believe it.”

“Well, later today, you’ll get to see it happen,” said Jennifer. “I remember how astonished I was when I saw it in action the first time. The tour this afternoon should be like a walk through an amusement park for you. But right now, I want to make sure the concept at least makes sense.”

“It does,” I said. “I’m just not sure how to make it happen.”

“Fair enough,” said Jennifer. “Let’s get back to our discussion so we’ll have time for the tour. In our diagram, is there one point at which we could initialize the work that would enable every other activity to know what to do next?”

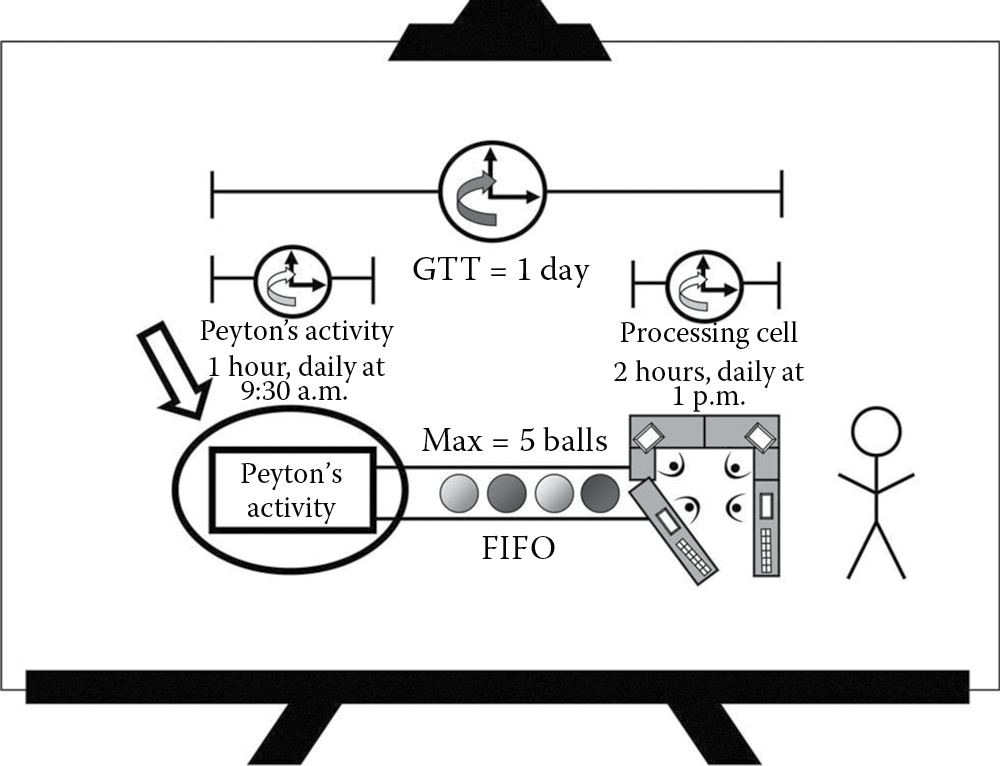

Not getting a response right away, she went on. “Let’s look to the left of the customer. We have a processing cell operating on a workflow cycle of 2 hours each day. The jobs come to it from the FIFO lane and are then processed. The processing cell always knows what to do next because the FIFO lane maintains the sequence of work that comes from Peyton’s activity.”

She drew a circle around the box at the left and put an arrow over it (Figure 8.3). “Peyton’s activity is the only one that needs to be scheduled because the processing cell will know what to work on next based on what comes to it in the FIFO lane. So, Peyton’s activity is where we would initialize the work.”

Work is initialized at only one process or activity in the flow, usually as far upstream as possible.

Jennifer pointed at Peyton’s activity and said, “This is the first activity. How does Peyton know what to do? Well, Peyton’s work comes in from the customer. In this example, the customer requests a ball, so Peyton processes the ball and then puts it into the FIFO lane. After that, we have either continuous flow or FIFO all the way to the customer, so the sequence of work never changes.

“The reason we aim for door-to-door flow in our business processes is so the work goes out in the same order it comes in. Once we introduce work at the initialization point, the sequence never changes, and this establishes a guaranteed turnaround time for the entire office.

“It’s important to become aware of problems at the initialization point because this is the first place, and sometimes the only place, where work is sequenced for every other activity and processing cell in the office. If we have issues there, then we’ll end up with irregular flow, and that’s when managers tend to want to jump in.”

“It seems that our initialization point might have a bit of uncertainty around it if we need to follow up on certain customer requests or clarify information,” I said. “Also, priorities can be adjusted at this point before work is released into the flow. Is that accurate?”

“Yes,” answered Jennifer. “But it’s limited to this one process in the flow. If a customer request isn’t sufficiently complete to process when we receive it, unfortunately, we can’t release it into the flow. We would need to clarify information or request missing data, and we would need to develop standard work to do it. Even though there might be some uncertainty at the initialization point, after that, we’ve essentially eliminated the chaos that used to exist because it all takes place up front now. We also want to put standard work around how the sequence is determined at the initialization point so the same sequence will be generated no matter who is handling the process. Does that answer your question?”

“Yes,” I said. “But what about setting priorities at the initialization point?”

“Ah, I see what you mean,” said Jennifer. “Having a robust initialization point allows the business to rearrange work any way it wants before fixing the sequence and introducing it into the flow. If certain types of work are more important than others, maybe because of the customer or the amount of work involved, then this is a good place to sequence the work to account for these realities while still ensuring the sequence can be preserved through the entirety of the flow. Is that a more comprehensive answer?”

“Yes,” I said. “It’s a lot to digest, but I understand the concepts.”

“Also, keep in mind that although we move all the clarification up front to this one process, it’s still a waste of time,” said Jennifer. “If we can minimize clarification, then we should. But, removing all the uncertainty and reprioritization from the activities that come after the initialization point is what allows us to establish a guaranteed turnaround time for the office.

“If we set priorities at the initialization point, sequence jobs there, and have flow all the way after it, would there ever be a need for prioritization? Why or why not?”

“Once a job is in flow, we don’t need to shuffle anything around since the desired sequence of work has already been established and is preserved all the way to the customer,” said Peyton. “Since every job has a guaranteed turnaround time associated with it, we’ll always know when a job should be complete. Each job is already being done as quickly as possible, so why would we want to interfere with that? Unless it’s due to outside factors, then we can use the sequencing point concept you described previously.

“Otherwise, I’d probably just check to make sure we were using the correct takt capability and verify that our standard work is correct. It seems like it would make more sense to critique the system rather than expedite a specific job, which would ignore the underlying problem.”

“But, what happens when the information on a claim finally comes through and now it’s a rush because it’s so far behind?” I asked. “Surely, we’re not just going to let it wait in line behind all the others.”

“Unexpected things will always happen,” said Jennifer. “We can’t predict everything, but we’re always going to try to let the system handle anything that comes up because it’s designed to be flexible. For example, if a claim is in rush status, we could run our workflow cycles more frequently or perhaps start them a few hours earlier. The point is that we’re going to look to the system when something unexpected happens, not to the decisions of managers.”

“OK, that makes sense,” I said.

“Then I think we’re ready to shift gears,” said Jennifer. “Until now, we’ve been talking about the first part of the definition of Operational Excellence. Who can remind me what that is?”

I spoke up and said, “Where we see the flow of value to the customer.”

“That’s right,” said Jennifer. “Everything we’ve covered has been necessary for us to see the flow of value to the customer, but let me ask you this. Why are we creating flow in the first place? What’s so good about flow?”

Peyton and I sat quietly for what seemed like a few minutes before I answered.

“Well, creating flow is the best way to eliminate waste.”

I was confident in what I’d said, but I got the sense that Jennifer was after something deeper.

“This is a tricky one,” she said. “Although it’s true that creating flow is the best way to eliminate waste, the real reason we create flow is simply so we can see when flow stops. If flow has stopped, then we know something has gone wrong, and we can step in, fix it, and get the flow back on track. Actually, you and I won’t step in. The employees will, and this gets us into the second part of the definition of Operational Excellence, fixing flow before it breaks down. The next two guidelines explain how to create a system that lets us know if things are going right or wrong and how we can set up our employees to fix flow before it breaks down.”

Pitch

Jennifer continued: “Next, we’ll look at something called pitch, which is used for two purposes. First, it lets the people in the flow see if things are going right or starting to go wrong, and second, it enables everyone else to know if information will get to the next activity, processing cell, or FIFO lane on time.

“Now that we understand the way knowledge and information flow in our office and how and why they are initiated at only one point, let’s talk about how we can see if things are going right or wrong, and how often we should do so. Do you think we can we see how well things are going in today’s offices?”

“Is that a rhetorical question?” asked Peyton. “Because to me, the answer is, not really. Any checks by management happen in meetings or are totally random, kind of like a surprise audit. But, in their defense, they have no way of knowing if everyone is completing their jobs on time unless they stand over their shoulders and watch them work.”

“Sometimes, that kind of micromanagement is what drives changes in priorities,” I added. “That, and not knowing when the work will be completed.”

Jennifer knew she struck a chord with her question. “Your responses are spot on. Let’s think about how often we should know if our system is keeping up with customer demand. Should a manager know every Friday so he or she can prepare an end-of-week report? Probably not, because if customer demand has changed during the week or things have fallen behind somewhere, then there wouldn’t be enough time left to do anything about it.”

Peyton and I nodded in agreement. “I’d want to know there’s a problem as soon as one arises,” I said.

“Fair enough,” said Jennifer. “But, how would you actually go about doing this? Would you walk through the office every hour to see what’s on time and what’s behind by asking each associate how it’s going? If you took this approach, how much time would you spend at your desk getting your own work done? What signs would you look for when strolling around that would tip you off to a problem?”

“I’m not sure,” I said. “I’d know a problem if I saw one, though, but I guess I probably would spend a lot of time asking questions and trying to fix things.”

“You’re exactly right,” said Jennifer. “I don’t want you fixing anything. We want to use pitch to tell everyone when things are going right or starting to go wrong. We also want to establish a predetermined time at which we know our system is keeping up with the rate of customer demand. Pitch gives everyone a true sense of the pulse of the office and also a feeling of accomplishment.

“A good pitch would be moving work from one activity or processing cell at a preset time and delivering it to the next process in the flow. Either the work moved at the preset time or it didn’t. If it didn’t, then everyone knows something is wrong. Because this can be tough to do in the office sometimes, we can even put up a signal like a flag to indicate if the flow is on time or behind. A green flag would mean everything is normal, while a red flag would mean something has gone wrong.

“To be clear, this is not about how often a manager or supervisor checks on the associates working in his or her area. Rather, it’s about how often the associates know whether the flow is working the way it’s supposed to. Pitch measures the system, not the people operating it.”

Jennifer gave us time to grasp what she said, then continued. “Pitch is not always easy to create, but it should have four important attributes. Pitch should be visual, physical, binary, and anticipated.” She went over to the easel and wrote these attributes down (Figure 8.4).

“Let me explain a bit more. By visual, I mean we should be able to see whether we’re on time without asking anyone. By physical, I mean some activity must happen, like a file is moved, a tray is emptied, a flag is raised, and so on. The best physical activity is actually moving work from one process to the next, but this is hard to do sometimes. By binary, I mean the flow happened or it did not, and by anticipated, I mean that we should know when the pitch is going to happen before it does, every time.

“So, how often should we know if the system is meeting customer demand?”

“Beats me, but I’m sure you’ll be able to clear it up,” I said.

“Thanks for your confidence,” said Jennifer. “Like we agreed before, knowing at the end of every week is too infrequent. How about the other end of the spectrum? Imagine if our office processes worked really fast, let’s say 3 minutes per job. Would we want to know every 3 minutes if the system was working?”

“No way,” I said.

“Why not?” pressed Jennifer.

“Because if something went wrong, there wouldn’t be enough time to do anything about it. There’s no way anyone could react and fix things inside a 3-minute window. Plus, my associates would get sick of me if I wanted to know about their progress every 3 minutes.”

“Very good,” said Jennifer. “Depending on what you do in your office and how long your jobs take, the time increment used can vary. Generally, though, a good time increment for pitch is at the end of a workflow cycle, specifically, when a processing cell has finished.”

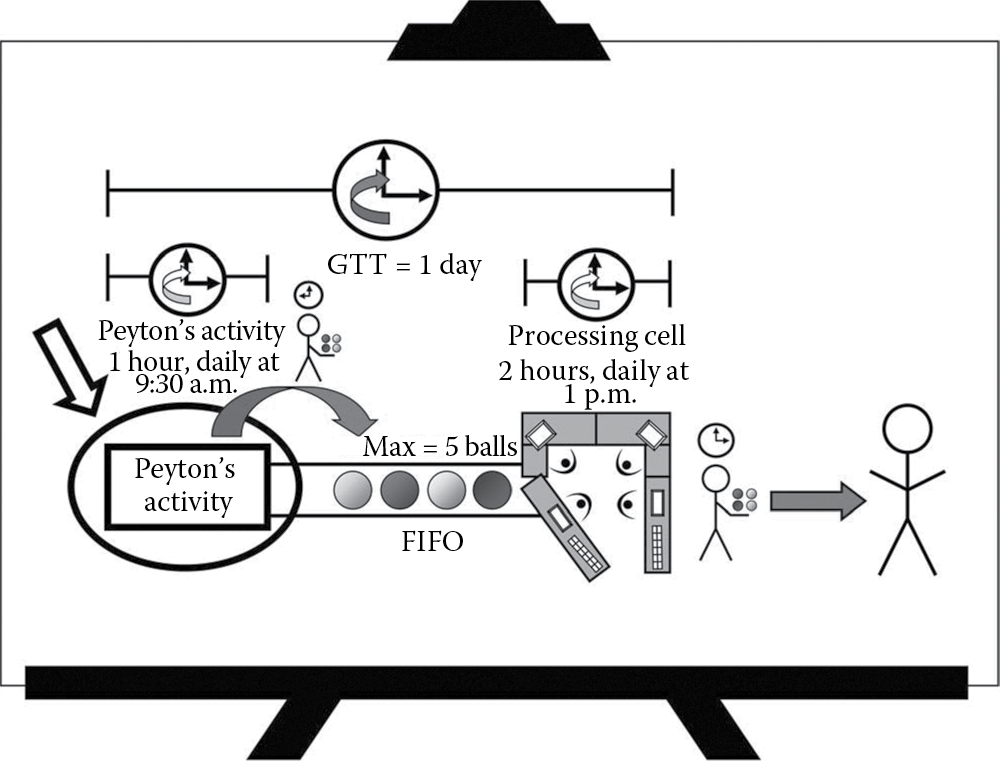

She went to the easel and added more detail to the previous example (Figure 8.5). “The figure carrying the balls would be the person moving information to the next processing cell, activity, or even FIFO lane,” said Jennifer. “Don’t worry about the number of balls. In real life, this person would move the amount of work that was completed at the end of each workflow cycle. The clock above him means this happens at preset times. Just like the illustration, this can and probably will happen at different times for different processes. The flag system could be used here, too, to indicate if the flow is on time or behind.

Pitch could be created at the end of “Peyton’s Activity” and at the conclusion of the processing cell.

“Don’t worry if you miss your time target in the beginning. In fact, you likely will until the associates become comfortable with the new way of doing things. Remember that pitch is a check on the system, not the people operating it. Make sure your people understand this; otherwise, it can be pretty discouraging if the time target is repeatedly missed. Notice that I didn’t say when the associates miss the time target. The success of pitch depends not only on how you deal with the technicalities involved, but also on how you introduce it to your people and how they understand it.

“What really counts, though, is what the people in the flow do when they see it’s starting to break down, because that means something has gone wrong and needs to be fixed. What we do about it and how we handle it brings us to our next and last guideline.”

At that point, our lunches arrived, so we took a few minutes to get the food unwrapped and agreed to continue our discussion as we ate.

Changes in Demand

“We’ve gone through eight guidelines so far,” said Jennifer. “We’ve established multiple takt capabilities and created continuous flow processing cells, FIFO, workflow cycles, integration events, standard work, single-point initialization, and pitch. We’ve even been able to set up a guaranteed turnaround time for the entire flow through the office. What more could we need?”

Jennifer paused, expecting Peyton and I to pick up the conversation from there, and Peyton took the hint and gave Jennifer a chance to get started on her lunch.

“Well, what about if we end up routinely exceeding our takt capability?”

“Great point,” I said. “But how exactly would we know we’ve exceeded our takt capability?”

“Our ninth guideline is something called changes in demand or, perhaps better put, reacting to changes in demand,” said Jennifer. “It’s going to really get into the second part of the definition of Operational Excellence: Fixing flow before it breaks down.

“First, we need to be able to react to the normal variation we experience on a day-to-day basis. This will be done through the FIFO lanes and workflow cycles we create. They will be flexible enough to absorb a temporary increase in demand. But, we have to recognize when the actual demand has increased on a more permanent basis, which is something we expect to happen as we strive for Operational Excellence. As we begin to regularly meet or exceed our customers’ expectations, it’s possible—and even likely—that they’ll reward us with more business, especially if we can outperform the competition. Operational Excellence is a foundation for business growth, and if we achieve it, our business will grow. But, more on that later.

“Right now, we want to address how we recognize and respond to changing customer demand. First, we need to understand what we normally deal with to know whether it’s becoming or has become permanently abnormal. Let’s look at a graph.”

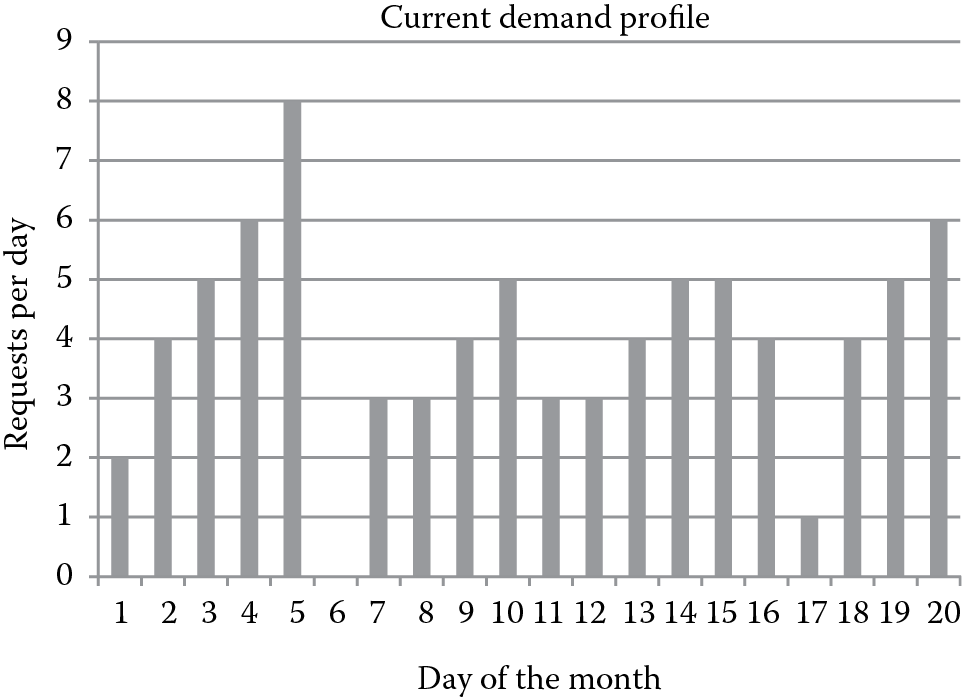

Jennifer handed us both a sheet of paper (Figure 8.6). “This is the actual demand we experienced 4 months ago. Note that the biggest demand days were every fifth day, or every Friday. As I mentioned, we determined that some of these peaks were self-imposed because one of our customer service associates was clearing his desk of any procrastinated work at the end of each week. This variation caused the demand to hit us in abnormal and irregular waves.

“We were able to eliminate this internally caused variation, but as you can see from the graph, we still had variation that we couldn’t get rid of. So, what do we do? How do we staff for something like this when we have persistent variation?”

“No clue,” I said. “I have this problem all the time, and I don’t handle it very well.”

“Let me help you out,” said Jennifer. “Earlier, when we were talking about takt capabilities, I mentioned that we need to establish multiple takt capabilities to account for specific ranges of customer demand. Then, we create different takt capabilities to handle the different ranges in demand we expect to experience over the course of time.”

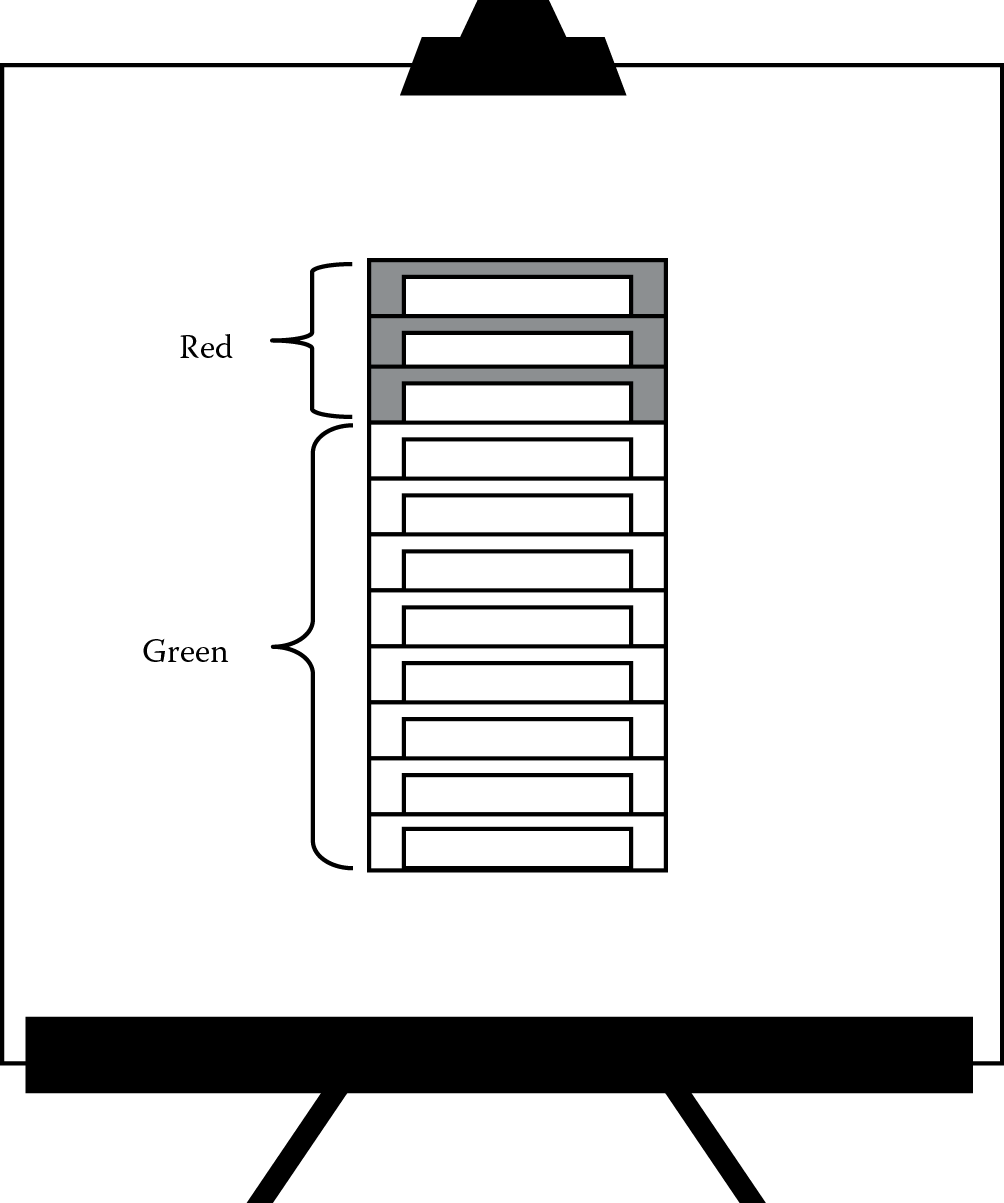

Jennifer went to the easel and drew something that looked like a time card rack. She added folders in each slot and indicated that the slots would be colored differently (Figure 8.7). She continued: “This acts as a FIFO lane for work, and the colors tell us if demand is what we expected or if it has increased beyond the established takt capability. If work is only in the green areas, then we know demand is normal. If it’s in the red, then we know demand is abnormal. If demand is in the red for a day or two, the team can make adjustments to how work flows through the office to keep up. Maybe they run a workflow cycle a little longer for those 2 days, but whatever standard work they use, it’s only temporary to handle a short-term spike. All of this has been preestablished so it’s ready to go before the associates even begin working for the day.”

“OK,” said Peyton. “So we know how we’re going to handle daily changes in demand that are temporary, but what if we’re in the red zone constantly and can’t ever get out of it?”

“That can happen,” said Jennifer. “When it does, we need to switch to another takt capability to handle the increased demand. There needs to be standard work for how to do this so the higher takt capability can be automatically deployed when needed. It might involve setting up parallel FIFO lanes or processing cells, creating new times for when the workflow cycles will run, creating a new pitch and, most important, new standard work for how the flow will operate to handle the increase in demand. It should be like flipping a switch, and everyone should know what to do once the switch is flipped because the response is preestablished.

“Having standard work for different takt capabilities gets to the heart of the second part of the definition of Operational Excellence: fixing flow before it breaks down. With this methodology in place, the associates can see flow breaking down and determine if the current takt capability is sufficient using the existing FIFO lanes and workflow cycles or if a more permanent alteration is needed. And, in case you haven’t guessed by now, this all happens without management intervention of any kind.

“Think of what would happen if we didn’t have standard work for when things go wrong. Typically, managers would become involved and change priorities, authorize overtime, or maybe just allow the jobs to be late. They’d make decisions, and decisions kill flow, but no more. Now, the associates can see that conditions are becoming abnormal, react to those signals, and fix the flow before it breaks down and negatively impacts the customer.”

“So, the system flexes to accommodate the daily variation we experience, and can even signal when we need to tap into our standard work for when things go wrong,” I said. “The associates, not the managers, are able to react to these changes and fix the flow before it breaks down. If we are in an abnormal state for more than a couple of days, then we know something else is going on and we need to switch takt capabilities. Is that right?”

Jennifer nodded, then continued. “All right, then. Before we go on the tour, keep in mind that I haven’t told you everything today. There are more concepts that help us in the office, things like knowledge shares, which have virtually eliminated meetings for us. By meetings, I mean when we bring people together and then try to influence, cajole, and arm twist to make decisions. Perhaps we can talk about knowledge shares the next time you come visit us.

“If there are no questions, we’re going to go on that tour I’ve been promising. While we’re out in the office and meeting with the team, feel free to ask questions. The associates you’ll be meeting haven’t rehearsed for this, so you should get nothing but honest answers. Are you ready?”

We both answered in the affirmative and followed Jennifer out of the conference room and into her world of Operational Excellence.

From the Author

The first six guidelines constitute the design of flow in the office and the final three describe how the flow will operate day in and day out. Together, they ensure that the office meets the established guaranteed turnaround time for the requested service. Because the last three guidelines detail the operation of the flow, they hold significant influence in achieving the guaranteed turnaround time.

Single-point initialization eliminates the tendency to reprioritize work once it enters the flow. If work must leave and come back, sequencing points are used. Pitch enables everyone to know if the flow is on time without asking questions or checking in throughout the day. Changes in demand create the ability to physically see if there is a need to switch to another takt capability and then do so, all without meetings or management intervention.

While the final three guidelines can have the greatest impact on the business, they can also be among the most challenging to implement, as they run counter to many traditional ways of working in the office. In most offices, the ability to reprioritize is central to management’s sphere of authority, as the flexibility it provides is intended to enable quick reaction. Similarly, status updates are meant to monitor the office to check each day that orders will go out and jobs will be completed. If that is not happening, then it is management’s responsibility to step in and do something about it.

With single-point initialization, pitch, and changes in demand in place, management intervention will rarely be needed, as the last three guidelines eliminate most of the causes that drive these practices in the first place. There will still be some management intervention in an office that has achieved Operational Excellence, as it is impossible to preplan for everything that might happen, but its occurrence will be greatly reduced.

While each guideline is important in and of itself, it is only together that they can provide a system of autonomous flow. No one guideline can individually reduce or eliminate management intervention in the day-to-day operation of the office, but together, and especially by implementing the final three guidelines to finalize the end-to-end flow, this is exactly what they can do.

To achieve Operational Excellence in the office, it is important to proceed through the guidelines step by step, in order, and not skip any of them. Overlooking any individual guideline will omit a critical piece of the design for flow and leave a deficiency that is impossible to make up or accommodate for elsewhere. This is a good point to emphasize when teaching the design guidelines, as missing or deliberately skipping any one of them will typically allow someone to make decisions on what to work on next, which would interrupt the design of how flow should work every day.