Chapter 9

The Tour

As we walked through the hallways to the industrial claims processing area, I had an unexpected feeling of excitement, like a kid at a birthday party about to unwrap the big gift. Jennifer had presented a really good case for Operational Excellence. She explained the need for flow, how to create it, and even discussed ways to identify broken flow and empower the team to repair it. It all made sense, and now I was looking forward to seeing it in action.

Just before we set foot in the office, Jennifer stopped us and said, “Let me give you a quick overview of what you’ll see on the tour. Generally speaking, we’re going to follow the flow from when a claim is initiated all the way through to the last step before it goes out to the customer. First, we’re going to visit the area where flow begins for industrial claims processing. After that, we’ll see a claims preparation cell, which prepares work for the claims processing cell, the last place we’ll visit. Any questions? All right, then; let’s get to it.”

We made our way to the first area. When we arrived, I stood back and took it in. There were two rows of cubicles separated by a center hallway. The row on the left was marked by a sign that said “Information Reconciliation—All Claims,” and the row on the right was identified by a sign that said “Industrial Claims Initialization Point.” I saw what looked like a first in, first out or FIFO lane feeding the row of cubicles on the right. It seemed like these two areas were connected, but I was not sure exactly how, so I turned to Jennifer.

“Does the reconciliation area feed its work to the claims area through that FIFO rack?” I asked.

“I’m glad you can see that,” she replied. “The reconciliation area handles all the incoming traffic for our industrial claims processing division as well as a substantial amount of volume for other areas, which means it’s one of our major shared resources.”

“OK, but why don’t the industrial claims people reconcile their own claims?” I asked.

“Good question,” she said. “As I’m sure is the case with your business, when claims reach us, they’re liable to be missing all sorts of information. To obtain that data, we may need to contact several people from different departments or even doctors, hospitals, patients, and other outside entities.

“So, instead of randomly chasing the missing information, we set up workflow cycles and bring people together at preset times every day to acquire it. Any requests for information or clarification take place right here, whether the source is internal or external. The associates reconcile claims while they’re together and then feed them to the appropriate areas through FIFO. Remember, we don’t want to release claims with missing information into the flow because they’ll disrupt it.”

“So, you’ve essentially taken all the chaos that used to exist everywhere in the office and front-loaded it to this area,” I said.

“In a way, yes,” Jennifer replied. “We moved all of the variation that disrupted flow to the front where we can see it and address it. However, we also think of this area as one of the key points where we capture knowledge. Remember, in the office, we flow information and capture knowledge. Because we need to have certain knowledge to process the claim in flow, we make sure we have it before we release the claim. We can also use this knowledge as a reference point for future claims that present us with similar challenges. That way, we won’t have to try to solve the same problem twice, or even more often, like we used to.”

“That’s pretty interesting,” responded Peyton, as I nodded in agreement.

“And, what about the row of cubicles?” I asked. “What happens when claims enter the FIFO rack?”

Jennifer pointed to the cubicles on her right and said, “Once claims have all the information they need, the employees follow standard work to determine the order in which they are placed into the FIFO lane that feeds this area. This is the initialization point for industrial claims, the exact point at which claims are released into the flow for industrial claims processing.

“When an associate finishes the claim he or she is working on, the associate simply withdraws the claim that’s next in line in the FIFO lane. It’s first come, first served—no shuffling priorities, no changing the sequence. It’s already been set using standard work based on what’s best for the business. Once the claim hits the FIFO lane, it remains in that sequence all the way to the customer.”

“So, once a claim is pulled from the FIFO rack and released into the flow, there are no outstanding issues with it, right?” I asked.

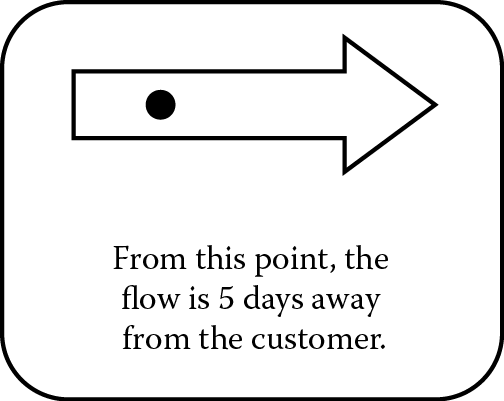

“That’s right, Pat,” said Jennifer. “Since the associates in the cubicles on the right have all the information they need, they should be able to do their work without any issues. And, because of the workflow cycles that govern this area, once a claim gets here, it’s guaranteed to leave within 3 hours. From there, the flow continues, and the rest of the workflow cycles kick in. Because of those workflow cycles, we know that at this point in the flow, each claim is precisely 5 days away from the customer. In fact, we’re so confident in that time frame, we even post it.”

Jennifer pointed to a sign that was fixed to the side of one of the cubicles (Figure 9.1). I had to admit, the sign was impressive. I gathered my thoughts about everything I’d seen and said, “It sounds like the biggest pain point for this area is that incoming claims still don’t have complete information. If you could move them through the information reconciliation area faster, you’d be able to get them out to the customer sooner.”

“That’s right,” said Jennifer. “That’s one of the things we’re going to address next. We’ll be working with our customers to develop flow-level standard work between us and them, which we expect will eliminate a lot of the chaos. Then, our next step is to teach our customers, doctor’s offices, hospitals, and so on the techniques they need to create guaranteed turnaround times for responding to our inquiries. Once we have more experience under our belt, we’d love to teach them about Operational Excellence in its entirety. Any questions about the initialization point?”

“It all seems to make sense, but it’s a lot to take in,” I said.

Peyton nodded, and Jennifer said, “Let’s continue and follow the flow to the next area, which is our claims preparation cell. This cell combines information from the customer, account managers, and adjusters and prepares it for the claims processing cell, which we will see after this. Everyone at the claims preparation cell will be busy, but we can pull some people away briefly to answer any questions you might have.”

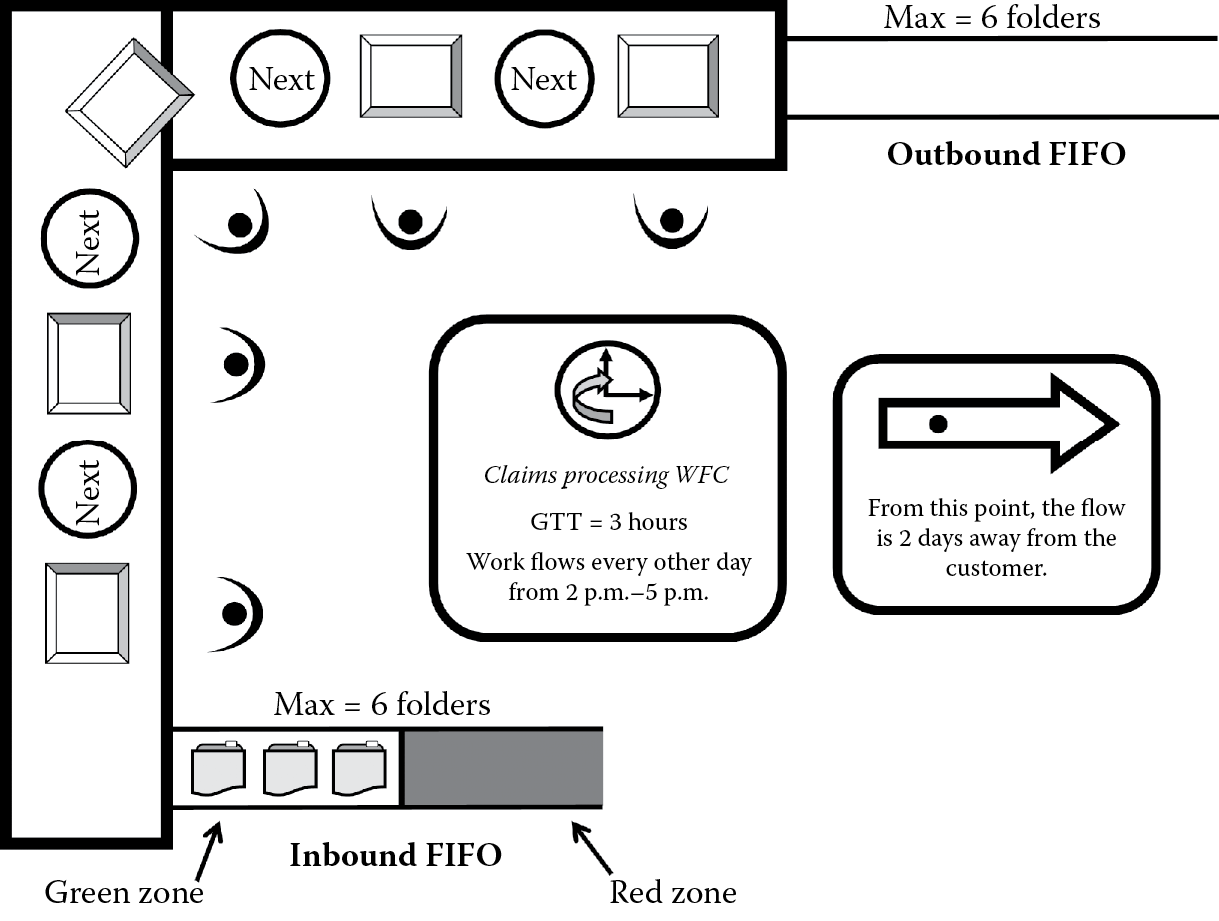

We made our way back through the corridors and headed toward a group of four people arranged around a set of tables. Before we got there, Peyton noticed something on the wall and stopped. I saw it, too, and said to Jennifer, “That looks like what you drew on the flip chart back in the conference room.”

I recognized the workflow cycle symbol, and the information below it identified this group of people as the claims preparation cell. It also said they flowed work every day for 4 hours, beginning at 1 p.m., and I noticed a sign I had seen at our first stop, but with different information here (Figure 9.2).

A sign indicating the name, timing, and GTT of the Claims Preparation Cell and another sign indicating that the GTT for the flow is 3 days once work reaches this point. WFC, workflow cycle.

“I’m surprised you recognize it, given my lack of artistic talent,” said Jennifer.

“Wow,” I said. “They’re so confident in their workflow cycles that they’ve posted their guaranteed turnaround times at every point in the flow.”

“Well, it’s true we post them, but it’s not because of confidence,” said Jennifer. “We want everyone to know not only how the information flows, but also the timing of the flow. Our goal is to make it so apparent that even a visitor can tell. So, what do you think? Are we successful?”

“Sure, I can follow it,” answered Peyton. “It’s quite easy. How about you, Pat?”

“Well, I’ve been in offices before that have lots of signs,” I said. “But I’ve never seen visuals like this that describe the flow. They’re intuitive, and I can easily follow them, but I do have a question. I saw a sign at the initialization point that said the flow is 5 days away from the customer. But here, the same sign says the flow is 3 days away. Have I missed something?”

“Not at all, Pat,” said Jennifer. “Don’t forget that there are different types of workflow cycles. Some are associated with the cells themselves, and others encompass the connections between the cells. Our initialization point connects to the claims preparation cell through a FIFO lane, and the work sits in the FIFO lane for 1 day before the claims preparation cell processes it. That’s why the initialization point is 5 days away from the customer and the claims preparation cell is 3, not 4.”

“I see,” I said. “So, the time associated with a workflow cycle could also encompass the wait time in the FIFO lane plus the time it will take the next area to process the work?”

“That’s right,” replied Jennifer. “Remember, workflow cycles refer to the rate at which work moves or flows within or between different areas or activities along a specific pathway, and they happen at preset times. A short pathway might be the processing cell itself, while a longer one might be the combination of two processing cells and the FIFO connection between them. We’ve tried to create ours so the associates in the workflow cycle can see the end-to-end flow within that cycle.”

“That makes sense,” I said. “It seems like that would help everyone see the flow of value, especially their part in it.” I focused my attention on the people in the claims preparation cell and asked Jennifer, “Can I ask some questions?”

“Ask away,” said Jennifer. She introduced me to one of the associates, a woman named Wendy, who occupied the first position in the claims preparation cell.

After the introductions, I asked, “So, how can you or anyone here know whether you’re on time?”

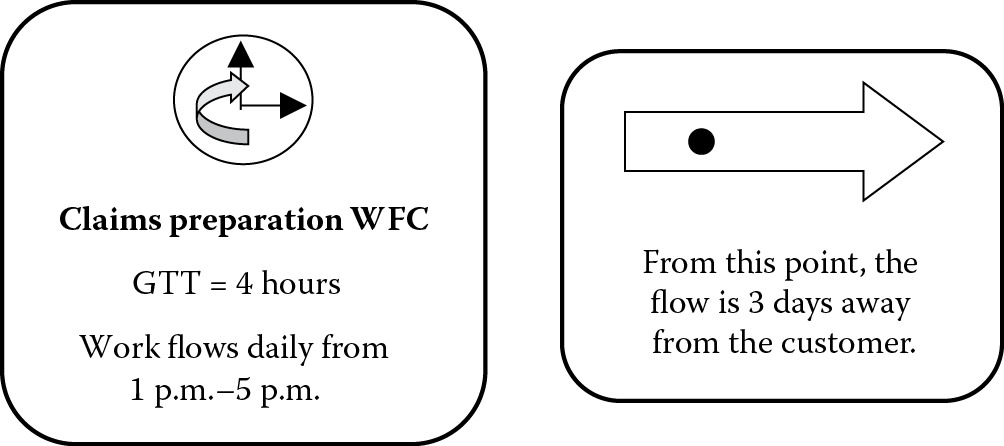

“Well, we’re able to monitor the flow throughout the day by that FIFO lane right there,” said Wendy (Figure 9.3). “It’s really a whiteboard that we turned into a FIFO lane.

A whiteboard turned into a color-coded FIFO lane. If work has backed up into the red zone, then the employees know something has gone wrong and abnormal flow exists, and they (not management) can take steps to correct the abnormal flow.

“The circles are whiteboard magnets and represent individual claims. We write the last four digits of a claim number on each magnet, so we always know what to work on next. When we’re ready to work on the next job, we remove the right-most magnet from the whiteboard FIFO lane and locate that claim. We’ve even color-coded the FIFO lane green and red to show us if things are going right or wrong. Green is good—everything is going OK. If work is in the red, we have to do something. We’re good right now, but if we received two more claims, we’d have abnormal flow, and we’d have to react to it. It’s a pretty easy way to know if we’re on time just by looking at the flow.”

“OK,” I said. “But when will your boss or supervisor know if things are on time?”

“Every day at 5 p.m.,” answered Wendy. “That’s when we normally finish processing everything, and we use pitch to show that, too. If he happens to just walk by, he can tell also by looking at the FIFO board. At the end of the workflow cycle for the claims preparation cell, we put a green flag on top of the tables here. About 5 minutes later, our supervisor comes around. If he sees the green flag, he knows everything got out on time today. It takes about 30 seconds out of his day. It’s that quick, and there’s an added benefit as well.”

“What’s that?” I asked.

“The boss hardly bothers us anymore, if you know what I mean,” she said.

“But, what if things haven’t gotten out on time?” I pressed. “Don’t you think he’d want to know before the end of the workflow cycle?”

“True,” said Wendy. “The boss can walk by any time and see if work is backed up into the red zone. If it is, he might check in with us to see if we’re following the correct standard work to deal with it or if we need any other help. Once in a while, we do, but not too often. Usually, we recognize we’re drifting into red territory, and we know how to take care of it ourselves. Even if he sees we’re continuing to work past our normal workflow cycle end time because of higher-than-normal customer demand, he knows we’re taking care of it.”

“Thanks,” I said. “That clears things up for me.”

“Any time,” said Wendy.

I was beginning to see what Operational Excellence looked like. Their supervisor only spends about 30 seconds a day checking to see if things are on time? That is incredible. I was anxious to find out more and recalled the five key questions for flow in the office Jennifer introduced me to earlier in the day. I decided to test them out on one of the people working in the cell. If the questions really were as powerful and meaningful as Jennifer said, then anyone here should be able to answer them. Since Wendy happened to be right next to me, I decided to ask her.

“Wendy, do you mind if I bother you for a few more minutes?” I asked.

“Not at all,” she replied. “What else can I do for you?”

“I just have some basic questions I was wondering if you could answer,” I said.

“I’ll do my best,” she said. “Fire away.”

“How do you know what to work on next?” I asked.

“That one’s easy,” said Wendy, pointing to the rack. “I do whatever is next in the FIFO lane right there. I just grab the next magnet, find the corresponding file, and get to it. It’s first come, first served.”

That also answered my next question, Where do you get your work from?

“All right. How long should it take you to perform your work?” I asked.

“Well, the claims are all a little different, depending on the type,” she said. “But, each type has a standard time associated with it, and I can usually process the claim in that amount of time.”

I was beginning to understand the power of these five questions. They took care of everything involved with normal flow and eliminated the need for management intervention.

“OK, last two questions,” I said. “Where do you send your work once you’re finished with it? And when you send your completed work, are you able to tell if flow is still normal?”

“Here I was worried that these questions were going to be difficult,” said Wendy. “Jennifer already taught us the five key questions for flow in the office. Once I’m finished with my work, I send it to the next person, who happens to be the account manager in the claims preparation cell. We even mark the exact location with a big circle that says ‘Next’ on it. The space should always be unoccupied by the time I go to put my file there. If the previous file hasn’t been taken from the space yet, then I know something is wrong, so it’s easy to tell if the flow is normal or abnormal.”

“Thanks again,” I said.

Wow, not only did Wendy know the answer to all five questions, but also she obviously understood their purpose. It was impressive to see how ingrained Operational Excellence was in the culture.

Wendy said her good-byes, and Jennifer motioned over someone else from the processing cell so I could talk to him. He introduced himself as Steve, and we distanced ourselves a little bit from the group.

“So, tell me the truth,” I asked. “Have the changes really made your life easier?”

“Oh, without a doubt,” said Steve. “Everything’s much more intuitive now, and we can all see how things are supposed to work. If there’s a problem, everyone can see it. Before, we just heard about it afterward from management. If I have any questions, I simply ask my neighbor, who is always there when we prepare a claim. We don’t have to chase people for information anymore, so there’s a lot less disruption in my day. In fact, I probably deal with half the number of e-mails and voice mails I used to, and we haven’t had any fiascoes with our customers in quite a while.”

Fiascoes—Mercy Hospital, the catalyst for my visit here, flashed into my mind, and all at once my work problems came rushing back.

“You said life is easier, but what about your customers?” I asked. “Do you think the changes have made them happy as well?”

“I think they might actually be happier than we are,” he said. “With the guaranteed turnaround times, we now know how far away a claim is from the customer at every step in the flow. We don’t have to guess any more, we know, and the lead time has gotten significantly shorter for everyone.”

“But, what about when there are problems?” I asked. “How is this process any better than the way things used to be done?”

“Well, problems are going to happen no matter what system you have. We certainly have fewer problems now than in the past, but when they do occur, at least we’re able to see them, react to them, and hopefully fix them before they have an impact on the customer, and we don’t need management standing over our shoulder all the time. That’s a big change from how things were before.”

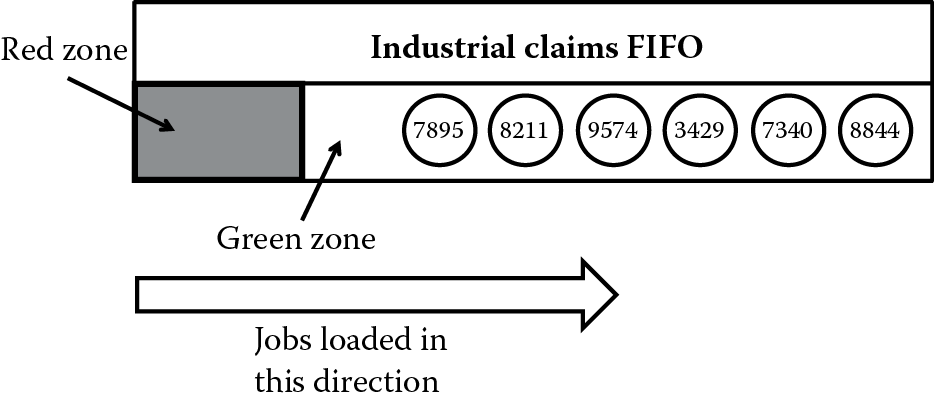

Jennifer came over and said we were ready to move to the last area. On the walk, she reminded us we were going to see the claims processing cell. We arrived at a conference room, smaller than the one we had been in all morning. It had some tables, computers, and chairs, and between the computer terminals were circles with the word Next written in them. I could also see inbound and outbound FIFO lanes, and the inbound one seemed broken up into two sections, one red and the other green. I also saw two signs I was familiar with by now (Figure 9.4).

“This is the claims processing cell,” said Jennifer. “Just like at our last cell, remember that we really have two levels of workflow cycles here. One governs the claims processing cell itself, and the other governs the connection between this cell and the claims preparation cell. They’re both important because only together do they create a guaranteed turnaround time for the entire flow.”

Right at 2 p.m., a group of five people came in, sat down, greeted each other, and began working. Jennifer walked us around to the different associates and introduced us. All of them said that if we had any questions, we should feel free to ask. Rather than jump right in, Jennifer suggested that Peyton and I stand back and watch them work for a little bit.

After observing for about 10 minutes, I saw something remarkable happen. One of the associates in the flow took a folder off a circle that said “Next” on it, opened it up, examined it for a few moments, and then sent it back to the previous associate. I motioned for Jennifer to step outside the conference room so I could ask her a question.

“What just happened there?” I asked. “I saw someone pick up a folder like they were going to start working on it, but instead they just returned it.”

“Well, I can’t say specifically what happened without going over and asking,” said Jennifer. “But, I’m pretty sure the previous associate in the flow did something wrong on the file, so it was sent back.”

“Just like that?” I asked. “No one had to check or approve it?”

Jennifer looked slightly puzzled at my question. “No, why would they? Each associate knows what work they should receive, so if something is missing, they just send it back. That’s one of the great things about flow. Before, the associate would put the folder on his or her desk and, of course, stop the flow. Then, the voice mails and e-mails would begin.”

I remembered what Steve had told me earlier about the number of his voice mails and e-mails being cut in half.

“In the processing cells, the associates are able to see flow beginning to break down and take steps to fix it, without a meeting and without management intervention,” said Jennifer.

I nodded, and we returned to the claims processing cell. Jennifer noted that everyone always knows what to work on next because they are working in flow that happens along a preset pathway. I asked her if I could ask one of the associates a question, and she said it was not a problem, so I went up to the first associate in the processing cell.

“Excuse me,” I said, pointing to the rack of folders that made up the FIFO lane. “I was wondering if you could tell me why your inbound FIFO lane is divided into two sections.”

“Sure thing,” came the reply. “That’s how we’re able to tell what the customer demand is for the day. There are two sections to the FIFO lane, red and green. Depending on how many folders we have on a given day, we make adjustments as needed. If only the green section is filled, we don’t run the workflow cycle for the full 3 hours.”

“Are there any meetings or managers involved in the decision?” I asked.

I got a look that suggested I should have known the answer already. “We haven’t done that in a while. We just take care of it ourselves. We like it that way. Besides, my manager’s got more important things to do with her time.”

I went back to where Jennifer and Peyton were standing, then Jennifer led us out of the conference room, saying thank you to the associates as we left. Once outside, I had one more question.

“How has Operational Excellence affected your ability to hit your promise dates?” I asked Jennifer.

“It’s had an extremely positive impact,” she replied. “We’ve not only significantly reduced the overall claims processing time, but we’re able to hit the new time consistently because we have workflow cycles and guaranteed turnaround times at the cell and connection level everywhere in our flow. We know this because it’s one of the things we measure. After all, in business, you are what you measure.

“Think of it this way. Imagine you were the supervisor or manager in charge of the claims processing cell we just saw. As a leader, if you knew that group flowed information for 3 hours every other day, would you need to chase after them to find out when their work would be finished?”

“Well, it’d be a bit of a mental adjustment to make, but I suppose not,” I said. “If this is the way things worked all the time, then I wouldn’t need to call people and ask them when they were going to complete their work.”

“That’s right,” said Jennifer. “That’s the power of having workflow cycles and guaranteed turnaround times.”

OK, I thought, that makes sense. The workflow cycles and guaranteed turnaround times eliminate the need to constantly check on people.

Jennifer turned to both of us and said, “OK, there’s one final question I have to ask you both, and it’s one that tests how well we’ve done in this area. Take a quick look back inside the conference room.”

We did as she asked and then came back outside. “Can you tell if our flow is on time right now just by looking? Are things normal, or is there a problem?”

Neither one of us was expecting this question. We took one more look at the processing cell, and Peyton was first to respond. “Everything looks fine. I don’t see anything in a red zone, so it looks like they’re on time.”

“I agree,” I added. “Work hasn’t accumulated past the green zone of the FIFO lane, so it looks good.”

“That’s right,” said Jennifer. “Just remember, the point isn’t that everything is going well right now, although that’s of course good. The point is that you can tell if it is just by looking—no questions, no meetings, no status updates.”

She paused for a few moments to let that sink in. “Are you ready to head back to the conference room and wrap up?”

Peyton and I both nodded and followed Jennifer back through the corridors. When we got to our conference room, I had some questions about the tour, so we all sat down.

“Everything looked very impressive, and I’m not only talking about the flow, but also the associates’ attitudes,” I said. “They were proud of the changes. In my office, well—people like doing things their own way. If you try to change anything, it just leads to meeting after meeting. How did you get the associates not only to do things differently but also to enjoy doing things differently?”

Jennifer let out a deep breath. “That’s an excellent point,” she said. “The physical changes to the office are one thing, but changing people is something else entirely. I’ll admit it was difficult. There’s a whole other chapter in change management that we didn’t talk about today.

“When we began implementing the new concepts, we encountered people who had been employed with the company for years, and they were very knowledgeable. Each person had their own method for getting things done, and I’m not just talking about the associates. I’m talking about their managers, too. At first, the managers didn’t want people leaving their areas to join processing cells or workflow cycles. They wanted them to be available to work on priorities.

“We had to educate everyone on the concepts of Operational Excellence and how we use it to grow the business. Creating awareness and aligning the managers was key. We had to teach everyone that it’s not about increasing efficiency. It’s about creating a foundation for business growth.

“Most people didn’t see why we needed to create flow and establish standard work, but some did, and we worked with those people first. It was easier to persuade everyone else to give it a try once they saw it in action. We gave them some ownership in growing the business, too, and this helped put everyone at ease. After all, everyone wants to see the company grow.”

“That makes sense,” I said. “It also sounds like quite a bit of work.”

“It sure does,” added Peyton. “But, then again, they did it here, and it’s unlike anything I’ve ever seen. It’s quite an accomplishment. You must be proud.”

“We couldn’t have done it without the associates,” said Jennifer. “They’re the real reason for our success. I give them all the credit.”

Peyton and I both nodded.

“There’s something else from the tour I want to ask you about,” I said. “All the work was passed in folders. It was all hard copy, and even the magnets I saw on the whiteboard FIFO lane represented physical work. Everything could be held in your hand. But, in many offices, the work is all electronic. In large companies, people send e-mails back and forth from different buildings and may never be in the same room. What do you do in situations like that?”

“That’s a great question,” said Jennifer. “We still want to follow the same process and use the same techniques we’ve been talking about. However, the application will be a little different. Let’s just say there are many ways to create end-to-end flow by following the guidelines. The only limit to your specific situation is your creativity. If you can find a way to answer the five key questions for flow in the office, you should be OK.

“For example, we can create rules for our e-mail inboxes so messages are sent into electronic FIFO lanes via different preestablished subfolders. From there, we’d process each subfolder on a workflow cycle, the same way we process work in the FIFO racks and boards you saw on the tour. Off-site locations would establish their own workflow cycles to flow information to each subfolder by the time it’s needed.”

“I can see how the guidelines could simplify the flow between different branches all over the country,” said Peyton.

“That’s exactly what they’ve done for us,” said Jennifer, pausing before continuing. “Great discussion. Your questions have reminded me just how much we’ve accomplished. Before we conclude, I want to thank both of you for taking time out of your day to come here and visit with us. I hope you learned a lot of practical knowledge so far, but we’ve got one more critical topic to cover, so I’d like to wrap up with a final thought. I’d like for you to think of what it is you didn’t see while we were out on the tour.”

Peyton and I both looked at each other for a second, then thought about it. What did we not see? There could be a million different answers to that question, but I sensed Jennifer was after something specific. I thought back to the conversation we had just had about workflow cycles and guaranteed turnaround times and how Peyton and I knew the claims processing cell was on time just by looking, and then it hit me.

“Managers,” I said. “We didn’t see any managers or supervisors on the tour. No one was walking around checking on things or putting out fires. We also didn’t see any hot lists, expedites, or changing priorities. There weren’t any meetings taking place in any of the open rooms either. Does management even have meetings to set priorities anymore?”

“Not really,” replied Jennifer. “We had a few when we first implemented the system, but we’ve virtually eliminated them. Which leads me to my final point of the day: Remember one of the things we said earlier about Operational Excellence? It’s a foundation for business growth. Our objective is to grow the business. This is why Operational Excellence is the destination of the continuous improvement journey. A seamless, smooth-running operation enables managers to spend their time working on offense.”

Offense? I thought. Are we talking about football?

“Working on offense means performing activities that grow the business as opposed to maintaining or defending it,” said Jennifer. “Think about it. If you’re out there chasing claims, people, and resources all day, how will you ever have the time you need to grow your business? To grow your business, you need time. And our managers and supervisors now have time to work on offense.

“This is why we work so hard following and implementing the business process guidelines for flow. We do it for one reason: to give our people the time they need to grow the business.”

It all made sense to me now. The business process guidelines for flow were enough of a paradigm shift. To find out they were also a means to an even greater end—that was incredible. For years, I had just been trying to improve my office for efficiency and productivity, when I really should have been trying to improve it to grow the business.

I stood up to leave and went over and shook Jennifer’s hand, then Peyton’s.

“Thanks for everything,” I said. “Now, I’ve got to go back and convince my boss that I haven’t been dreaming all day.”

Jennifer chuckled a little before saying, “Don’t worry. It won’t be as hard as it seems. Just remember everything we talked about today, especially how Operational Excellence creates a foundation for business growth and frees up management to work on offense. If your boss is anything like mine, that’ll get eaten up.”

I thanked my companions once again and made my way out of the building and to my car. On the drive home and later that night, I could not stop thinking about what I had learned and seen.

How could I possibly explain it all to Chris tomorrow?

From the Author

One of the more challenging aspects of making flow visual is doing so with work that is primarily digital in nature. When the majority of work is performed and then transmitted via e-mail or “lives” in networked databases, work can too easily remain hidden from view, and making flow visual is a critical component of Operational Excellence. Without visual flow, it is difficult to distinguish between normal and abnormal flow in the day-to-day workings of the office.

While every effort should be made to make the digital work physical when practical to do so, sometimes the best we can do is represent digital work in some physical way. For example, a system of visual signals like flags can be used to indicate whether a processing cell has completed its work on time. In this case, the work itself has not been made physical, but insight into whether its completion is on time or behind has been created in a way that physically can be seen in the office.

A more dynamic workflow might involve a different solution to make the flow visual, perhaps by representing each piece of digital work in an engineering department via color-coded tokens on a magnetic whiteboard. The board can be divided into FIFO lanes per type of work. As the electronic work is processed through the designed flow first in, first out, the tokens are correspondingly moved on the whiteboard first in, first out. This enables everyone to physically see if the flow is on time or behind just by looking at the whiteboard, which acts as a window into the status of the digital work. The tokens could be moved at the end of every workflow cycle if it is not practical to move them in real time as the digital work is completed, as this would still provide insight into the timeliness of the overall flow by knowing if the workflow cycles had been completed according to the established guaranteed turnaround time.

Creating visual flow is key to preventing management intervention over the long term. Remember—your visuals for flow should be so good that even a visitor can tell if you are on time. Visual flow enables leadership to understand the status and timeliness of work on a day-to-day basis without asking questions. If there is a need to ask questions, then they can be focused on the system of flow, such as the following:

- Are the workflow cycles on time?

- Is the correct takt capability being used?

- Are we following the correct standard work for abnormal flow?

These questions focus on the system of flow, what (if anything) has gone wrong with it, and most important, what can be done within the rules of flow to fix something if it has gone wrong. It is vital that management responses stay within the boundaries of the system of flow created. Otherwise, the impression becomes that the designed flow is really only useful part of the time. Soon enough, however, “part of the time” begins to happen more and more frequently until the office is eventually dependent on management to get work to the customer again.

To this end, educating management is as important as educating the employees themselves. While there are many aspects of Operational Excellence and flow design that management should learn, among the most important teaching points is what questions managers should ask their teams. The questions should center on the key concepts of flow and Operational Excellence, but the common thread between them is that the managers should know the answers before the questions are asked. The intent is to confirm that the employees have the knowledge about flow and Operational Excellence that they should. If employees can answer questions about the end-to-end flow correctly, then it means they also have a solid understanding of its individual components and how they relate to one another.

Checking the employees’ understanding like this also provides a way for management to show active support for the transformation to Operational Excellence. This support assists in driving cultural change throughout the organization by sending the message that Operational Excellence is simply the way things are done, not just a passing trend, and this can help build momentum during the implementation once everyone sees that management is not only on board but also fully vested in its success.