Chapter 12

Managing Inventory and Other Assets

In This Chapter

![]() Recording the buying and selling of widgets, lingerie, haggis and much more

Recording the buying and selling of widgets, lingerie, haggis and much more

![]() Doing a head count of what’s in stock

Doing a head count of what’s in stock

![]() Balancing up your inventory account

Balancing up your inventory account

![]() Buying and selling motor vehicles, new equipment and other assets

Buying and selling motor vehicles, new equipment and other assets

![]() Calculating depreciation and keeping tabs on asset values

Calculating depreciation and keeping tabs on asset values

When I was writing this chapter for the first edition, Finbar, my (then) 10-year-old son, was looking over my shoulder. ‘What’s depreciation?’ he asked curiously, reading my detailed explanations about assets and asset values, and different ways to calculate depreciation. ‘It’s when something gets old’, I replied somewhat distractedly, ‘and it isn’t worth so much anymore. Depreciation is how you account for the decline in value of something.’

‘Hmm’, replied Finbar. ‘Does that mean you’re depreciating?’ ‘No’ came my terse response. ‘I don’t depreciate. I appreciate, meaning I’m more valuable and more beautiful with every year that passes.’ ‘No need to be so sensitive’, he shrugged. ‘Doesn’t sound like you’re appreciating much at the moment.’

I do appreciate that getting your head around asset valuations and depreciation is tricky, and that’s why I devote over half this chapter to that very topic. I also flesh out a subject that gives many novice bookkeepers grief — namely, how to account for the buying and selling of inventory, how to manage stocktakes and how to get your inventory account to balance.

Buying In, Stocking Up and Selling Out

You can account for inventory in two different ways: The perpetual method and the periodic method. With the perpetual method, you record the cost of goods sold with every sales transaction, and keep track of the current balance of inventory throughout the year. With the periodic method, you don’t account for the cost of goods sold with every sale, and instead you keep the balance of your inventory account static throughout the year. At the end of the year (or at the end of each reporting period) you do a stocktake, and calculate your overall cost of goods sold.

If you use accounting software, chances are you use a perpetual system, because the software easily calculates costs with every sale. If you do books using a spreadsheet, chances are you use a periodic system, recording stock levels at the end of each accounting period. I explain both methods in the pages ahead.

Buying inventory to fill the shelves

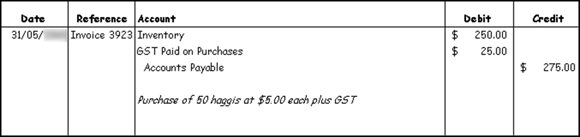

Okay, so I’ve just received my first shipment of haggis (which, for the uninitiated, is a weird kind of Scottish sausage that in olden days was sewn up using the lining of a sheep’s stomach). The haggis is made by a local supplier, at a price of $5 per unit, plus GST, and I’ve purchased 50 units of this delicacy. I show the debits and credits behind this transaction in Figure 12-1. (In this example, I’m using a perpetual inventory system. If I were using a periodic inventory system, I would debit Purchases instead of Inventory.)

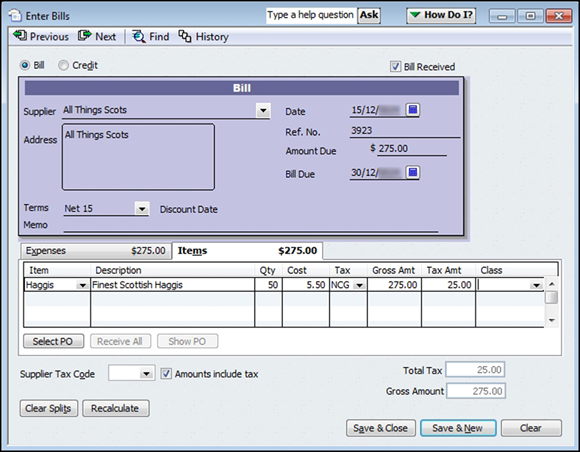

Of course, if you’re using accounting software, you don’t record a journal entry in this way. Instead, you record the supplier’s bill, simply increasing the number of items on hand. I show what this entry looks like in Reckon Accounts in Figure 12-2. Even though this entry looks completely different to Figure 12-1, the debits and credits behind this transaction are exactly the same.

Figure 12-1: Recording the purchase of inventory items.

Figure 12-2: When you use accounting software to record inventory purchases, the debits and credits are done for you.

Selling inventory to make a buck

Burns Night is approaching (that inebriated evening when the sentimentally inclined gather to remember Scotland’s national poet, Robbie Burns, who died some years ago in 1796), and I make my first sale of 10 haggis, at the grand price of $12 each plus GST. Och, this is a braw business.

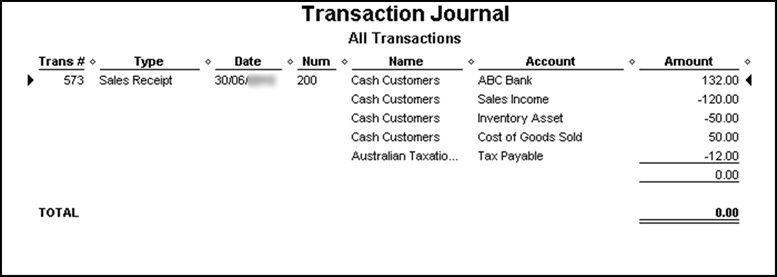

Because I’m working with accounting software (which uses a perpetual inventory system and tracks the cost of every sale), I simply type in the name of the customer, the number of haggis sold and the price. Easy. But in the background, the debits and credits are doing their stuff, as per Figure 12-3. (This journal is from Reckon Accounts, which shows debits as a positive figure, and credits as a minus figure.) The increase in cost of sales is what it costs me to make the sale, which corresponds to a decrease in inventory (because I now have less stock). The increase in the bank is because I’ve been paid, and this increase is represented by $120 in sales (which is the sell price before GST) and $12 in GST.

Figure 12-3: The debits and credits behind the sale of ten haggis.

If I didn’t account for the cost of each sale, and used a periodic inventory system instead, the journal would be more straightforward: I would simply debit Cash at Bank, and credit Sales and GST Collected.

Measuring the profits

Dusk is falling and it’s time for me to calculate how much profit I’ve made.

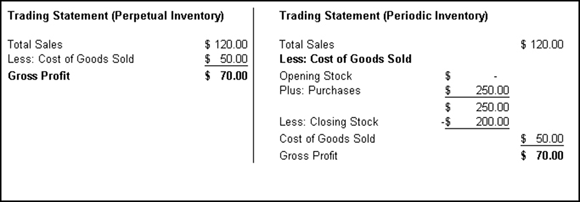

My accounting software uses a perpetual inventory system, and so I’m able to call up a quick Profit & Loss report. This report shows I’ve generated $120 in income (that’s 10 haggis at $12 each), with a cost of goods sold of $50 (10 haggis at $5 each), so I have a handsome gross profit of $70. I also still have 40 haggis left in my inventory, worth $200 in total.

If I were to use a periodic inventory system, my figures would initially be quite different. My report would show $120 in income, and purchases of $250, with a net loss of $130. But, as soon as I did a stocktake, I’d increase inventory by $200 and decrease purchases by $200.

You can see how both reports look in Figure 12-4, where I show the two formats side by side. This report summarising sales, cost of goods sold and gross profit is sometimes called a Trading Statement.

Figure 12-4: Trading Statements come in two possible formats.

Calculating the value of inventory

Accountants have about as many different methods of valuing inventory as you and I have had hot dinners. I could spend a whole chapter explaining different valuation methods, but instead I’m going to provide the briefest summary:

- Average cost: Average cost is calculated by dividing the current inventory value by the number of units in inventory. It’s as simple as that! (Average cost is the method favoured by most small business accounting systems.)

- First in/first out (FIFO): The first items you bring into inventory are the first ones you sell.

- Last in/first out (LIFO): The last items you bring into inventory are the first you sell. (This method is not usually acceptable for tax purposes.)

- Last cost: All inventory items are valued at whatever the last cost was for an item.

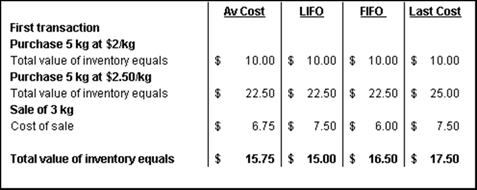

In Figure 12-5, I buy 5 kg of oats at $2 per kg, followed by 5 kg of oats at $2.50. I then sell 3 kg of oats, and calculate the value of stock remaining using four different methods. You can see how different the results are for each valuation method.

Figure 12-5: Different costing methods result in very different inventory valuations.

Organising Stocktakes

Things seemed fine until two days later when the computer crashed. Stay calm, I declared, we can restore the information from our backup. This we did, restoring the data from the day just before the stocktake. Never mind, I said, we’ll just type in the stock counts from the stocktake sheets one more time.

This is where the trouble hit. We looked high and low, far and wide, but the stocktake sheets had disappeared forever — through the shredder, I suspect. And so we did the stocktake all over again. What a way to spend a weekend!

However, here are a few tips to make sure things go swimmingly:

Avoid confusion: Before starting your stocktake, make sure you finalise all pending sales, and enter supplier bills for all goods that have already been received in the warehouse. Print a report showing stock at hand at this point in time, and then begin your stocktake. If possible, avoid recording any sales or receiving goods until the stocktake is complete.

Avoid confusion: Before starting your stocktake, make sure you finalise all pending sales, and enter supplier bills for all goods that have already been received in the warehouse. Print a report showing stock at hand at this point in time, and then begin your stocktake. If possible, avoid recording any sales or receiving goods until the stocktake is complete.- Be clear about what you need to count: Make sure you allow for goods in transit, goods on consignment and goods in delivery vans or in other locations.

Get the date right: If you do a stocktake on 30 June, date the adjusting journal 30 June, even if you enter stock adjustments several days later.

Get the date right: If you do a stocktake on 30 June, date the adjusting journal 30 June, even if you enter stock adjustments several days later.- Have a final check: After you record stocktake adjustments, your stock levels should be perfect, right? Make sure they are by printing a report showing final stock levels for every item and compare this against your stock count sheets.

- Keep records in a safe place: In the final wash-up, file your original stock count sheets and final inventory reports together.

- Make sure your inventory account balances: Skip to the following section to find out how.

My client likes this ‘perpetual stocktake’ method for a couple of reasons: First, his stock counts are now pretty accurate all the way through the year, which makes automatic re-ordering work a treat. Second, because he does stocktakes in bite-sized chunks, he has more time to figure out why stock levels are wrong, and fix the problem. Third: he can delegate the ‘zapping’ job to employees when the shop is quiet, making good use of staff downtime.

Balancing Your Inventory Account

In the perfect world, the total cost value of inventory in your inventory reports needs to balance with the value of your Inventory on Hand account in your Balance Sheet. For example, if you had only two items in stock — one tartan kilt at a cost of $200, plus one set of bagpipes at $2,000 — then the value of your Inventory on Hand account should be $2,200.

Of course, the world is not always perfect, and nor are you probably, and so every now and then you need to take the test. So, are you ready to give your inventory a quick health check? Grab the stethoscope and hold it to your heart. And then …

Generate a report that shows the total value of inventory that you have in stock.

For example, in MYOB you generate an Inventory Value Reconciliation report; in Reckon or QuickBooks Online, you generate an Inventory Valuation Summary report. You get the idea.

Now generate a Balance Sheet with the same date and look up the value of inventory on this report.

The inventory account is always an asset account and is usually called Inventory on Hand, Stock on Hand or something similar.

Check your pulse. Then compare the bottom line of your inventory report against the balance of inventory in your Balance Sheet.

Is your heart still beating? I hope so.

If the two balances match one another, your fitness regime is serving you well, and your inventory balances.

If your inventory doesn’t balance, you need to take action. My usual strategy is to work backwards in time, comparing the balance of my inventory account against the total of inventory reports at the end of every month, going back as far as I can go. If the discrepancy belongs to a previous financial year, you’re usually best to seek advice from the company accountant. Otherwise, keep repeating the comparison process, narrowing down the date range each time.

If you can see that inventory has gone out of balance on a particular day (for example, maybe inventory was in balance on 1 June, but out by $85 on 2 June), then scan every transaction on that day, looking for the out-of-balance amount. You should be able to spot the culprit, which is usually a journal entry made direct to the inventory account or an inventory item set up incorrectly.

Accounting for Assets

Recording the purchase and sale of assets is one of the more confusing tasks that a bookkeeper confronts. Recording the purchase of a new asset is complicated by tricky questions such as ‘When is an asset really an asset?’ and ‘When is an asset really an expense?’ Recording the sale of an asset is also tricky. Not only do you have to account for the gain or loss on the sale of the asset, but you also have to adjust the asset’s value to account for any depreciation that has been claimed since the purchase of this asset.

Note: When I talk about the purchase of assets here, I’m talking about the purchase of things such as new computers, tools or motor vehicles. I’m not talking about purchases of things like stock or raw materials nor am I talking about expenses such as advertising or telephone.

Figuring out if something is an asset or an expense

One of the weirder things about bookkeeping is what gets classified as an asset, and what gets classified as an expense. (This dilemma flows through to my personal life: I see those diamond earrings that I’d like for Christmas as an asset; my husband undoubtedly perceives them as an expense.) The distinction is pretty important. If something gets classed as an asset, you can’t claim a straight-out tax deduction. Instead, you have to depreciate the asset, claiming the cost bit-by-bit over several years.

So, what’s the dollar threshold when an asset becomes an expense? Keep the following in mind:

If an Australian business has a turnover of $2 million or less per year, simplified depreciation rules apply: If something costs less than $1,000 (before GST), you treat this purchase as an expense. Note: This threshold is constantly subject to change, and although I’m correct at the time of writing, please do double-check with an accountant or with the ATO that this information is still accurate.

If an Australian business has a turnover of $2 million or less per year, simplified depreciation rules apply: If something costs less than $1,000 (before GST), you treat this purchase as an expense. Note: This threshold is constantly subject to change, and although I’m correct at the time of writing, please do double-check with an accountant or with the ATO that this information is still accurate.- If an Australian business has a turnover of more than $2 million, normal depreciation rules apply: If something costs less than $100 (before GST), you treat this purchase as an expense. (Again, this threshold is subject to change, so double-check this information on a regular basis.)

- In New Zealand, the same laws apply for all businesses, regardless of size: If something costs less than $500 (before GST), you treat this purchase as an expense.

Recording new asset purchases

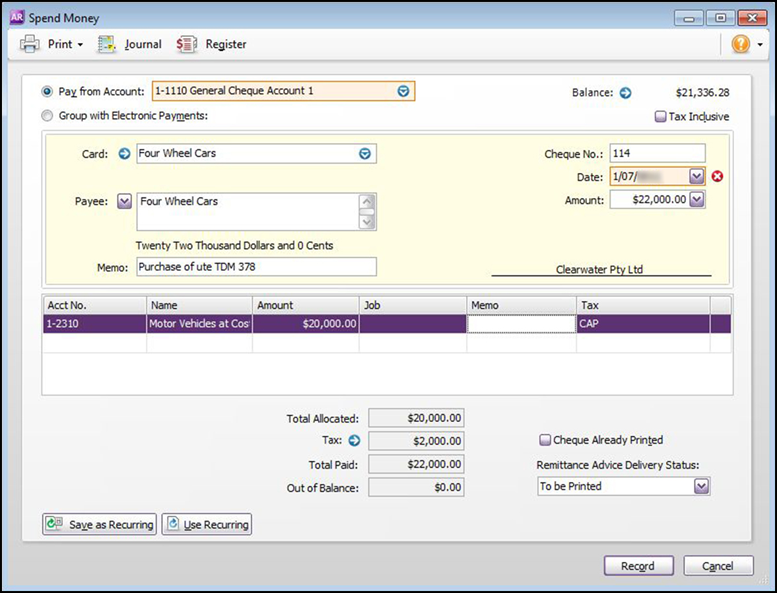

Recording new asset purchases is pretty easy stuff. You simply record the transaction in the same way as you record any other payment, similar to how I do in Figure 12-6. But before you finalise this transaction, check the following:

- Make sure you choose an asset account, not an expense account, to record new asset purchases.

- Always include a detailed memo for asset purchases, including serial numbers if possible. The accountant needs a decent description in order to add this asset to the depreciation schedule. (Note, however, that if your accountant chooses to pool assets when calculating depreciation, a schedule isn’t required.)

- In Australia, you report capital acquisitions (‘capital acquisitions’ is the fancy term the Tax Office uses to describe new asset purchases) separately on your Business Activity Statement. If you use accounting software, this means you need a unique tax code for this kind of transaction.

Also include associated costs such as accessories, installation and delivery as part of the cost of a new asset.

Also include associated costs such as accessories, installation and delivery as part of the cost of a new asset.

Figure 12-6: Recording a new asset purchase.

Recording the sale of assets

Imagine that the business you’re doing the books for purchased a ute three years ago for $22,000 (including 10 per cent GST), and that this ute has just been sold for $9,900. You have a wad of 99 greenbacks in your hot, sticky hands. What next?

If your turnover is less than $2 million per year, your accountant may record assets in two different ways: The first way is to list each asset on a depreciation schedule (see ‘Depreciating Assets, One by One’ later in this chapter for more info). The second way is to combine assets into a single ‘asset pool’ and depreciate assets as a group.

If your accountant uses the pooling method of accounting for assets, you simply allocate the sale of the value to the relevant asset account in your Balance Sheet. Easy. Things get a little trickier, however, if your accountant maintains a schedule for all assets. Here’s what to do:

Figure 12-7: Recording the sale of an asset.

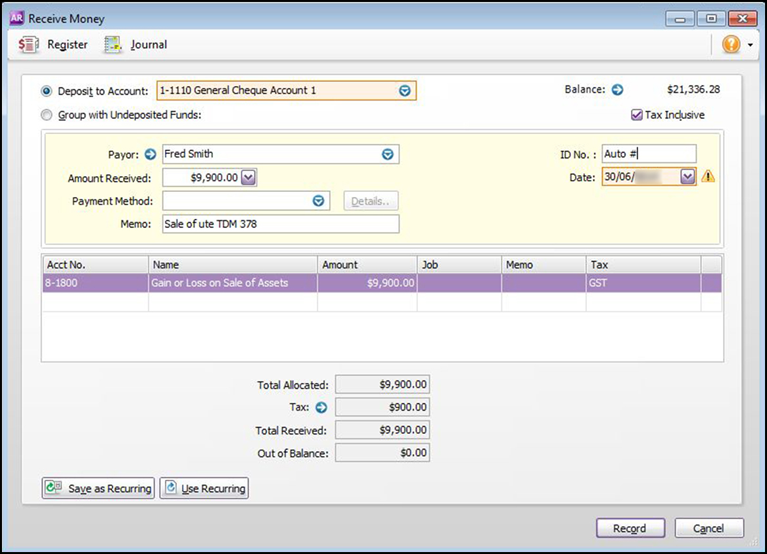

Record the receipt of money from the sale, allocating the whole amount to an account called Gain or Loss on Sale of Assets.

If you don’t have an account by this name already, create one now. (I know that not every cent of this deposit is a gain or a loss, but you’re going to adjust this account later in this process.) You can see how this receipt looks in Figure 12-7.

If you’re registered for GST, remember you have to pay GST on the sale of any assets. So if you sell a motor vehicle for $9,900, $900 of this transaction goes to your GST liability account.

If you’re registered for GST, remember you have to pay GST on the sale of any assets. So if you sell a motor vehicle for $9,900, $900 of this transaction goes to your GST liability account.Dig out the most recent Depreciation Schedule and look up the written-down value for this vehicle.

The written-down value is the original cost of an asset less how much has been claimed so far in depreciation. So if the ute cost $20,000 (less GST) and the business claimed $4,000 per year in depreciation for three years, the written-down value would be $8,000. (For more about depreciation, see ‘Depreciating Assets, One by One’ later in this chapter.)

Calculate the difference between the written-down value for this vehicle and the sell price, excluding GST.

If the written-down value is less than the sell price (excluding GST), the business has made a gain on the sale. If the written-down value is more, the business has made a loss.

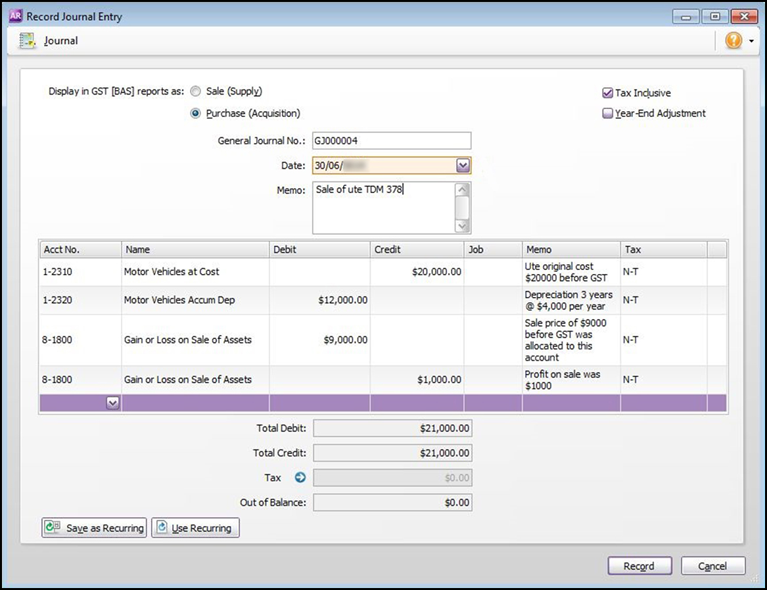

Make a journal entry, and on the first line, credit the asset account with the original cost of the asset.

In my example in Figure 12-8, you can see I credit my Motor Vehicle asset account with the original cost of the ute, which was $20,000.

On the second line of the journal entry, debit the accumulated depreciation account associated with this asset for the amount of depreciation claimed so far.

In Figure 12-8, I credit Motor Vehicles Accumulated Depreciation with $12,000 (having claimed $4,000 depreciation per year for three years).

On the third line, debit the Gain or Loss on Sale of Assets account by the amount (excluding GST) you received on the sale.

I received $9,000 before GST for the ute, so I debit this account by $9,000.

Calculate how much profit you made on the sale, and allocate this profit to your Gain or Loss on Sale of Assets account.

In my example, the ute was written down to $8,000 but I sold it for $9,000 (before GST), so there’s a profit of $1,000. I pop this amount in the credit column.

Check that your debits match your credits, and record this transaction.

And pop the cork on the bottle of champagne, you clever thing.

Figure 12-8: Recording the gain or loss on the sale of an asset.

Dealing with personal assets

What do you do if the owner of the business has already purchased an asset in his or her own name and is intending to use this asset for business purposes? (The most common example is a motor vehicle purchase.) Check out the following:

- If the business has a sole trader structure, you don’t need to worry about introducing this asset into the Balance Sheet. However, you do need to alert the accountant about the use of this private asset for business purposes, so that the accountant can correctly claim depreciation.

- If the business has a company structure and the owner requires to be reimbursed for this asset, you record the payment of the reimbursement in the same way as you’d record the purchase of an asset from any third party.

- If the business has a company structure but the owner is happy for the company to make use of this asset, I suggest you seek advice from the accountant. You may need to set up a regular motor vehicle allowance reimbursing the company director for all out-of-pocket vehicle expenses.

Depreciating Assets, One by One

Purchases of assets such as land, buildings, tools, equipment and computers have lives that go beyond a single accounting period. For this reason, you don’t write off an asset as a business expense in the year that you buy it. Instead, you write off a portion of the cost every month or year for the life of the asset.

For example, if you just bought a new $20,000 mahogany desk for your business and justified your purchase by mumbling as you paid the bill, ‘This is a great tax write-off’, prepare to be disappointed. You can’t claim the entire $20,000 as an expense this tax year — you can only claim the depreciation.

Depreciation is the process whereby accountants argue, ‘This bit of gear has an average life of ten years. You can claim the cost bit-by-bit over this period’. Every time you claim a bit, this action is called depreciation. Accountants have a list of the estimated life span of every possible different kind of asset (from a garbage compactor truck to a massage table) and they use this list to calculate how much depreciation you can claim each year.

Depreciation is the process whereby accountants argue, ‘This bit of gear has an average life of ten years. You can claim the cost bit-by-bit over this period’. Every time you claim a bit, this action is called depreciation. Accountants have a list of the estimated life span of every possible different kind of asset (from a garbage compactor truck to a massage table) and they use this list to calculate how much depreciation you can claim each year.

Calculating depreciation

In real life, the job of calculating depreciation normally falls to the accountant, and not to the bookkeeper. However, I often find that bookkeepers make errors when accounting for assets, partly because they don’t understand how the whole depreciation thing works. And so, in the spirit of becoming a bookkeeper who’s truly ‘ahead of the pack’, read on.

Note: In this section, I’m talking about how to calculate depreciation if your accountant maintains a depreciation schedule for all assets. If your accountant uses the pooling method of accounting for assets, skip ahead to ‘Depreciating using asset pools’.

- The original cost of the asset: Remember to include additional costs such as delivery and installation, but don’t include GST.

- The method of depreciation: I’m going to focus on the two most common methods: Prime cost (also called straight-line) method, and diminishing value method.

- The estimated useful life of the asset: Both the Tax Office (Australia) and Inland Revenue (New Zealand) have long lists of schedules listing every asset imaginable, and how long they estimate the useful life of this asset to be.

- How much has been written off this asset so far: If this asset has already been depreciated, you need to know how much depreciation has been claimed so far.

Depreciating using the prime cost method

With the prime cost depreciation method (also sometimes called straight-line depreciation), you spread the cost of the asset evenly over the number of years you estimate the life of the asset to be.

Imagine you purchase a new forklift truck for $30,000 and you estimate the life of this forklift to be five years. To calculate annual depreciation, you simply divide the cost of the asset by the estimated life. In other words, $30,000 divided by 5 equals $6,000, and so the annual amount of depreciation you can claim is $6,000 per year. (Alternatively, to calculate the depreciation rate, you divide 100 by the estimated useful life: 100 divided by 5 equals 20 per cent.) Table 12-1 shows the decline in value of this computer over the course of five years using this method.

|

Table 12-1 Claiming Depreciation Using the Prime Cost (Straight-Line) Method |

|||||

Year 1 |

Year 2 |

Year 3 |

Year 4 |

Year 5 |

|

Cost price |

$30,000 |

||||

Opening written-down value |

$24,000 |

$18,000 |

$12,000 |

$6,000 |

|

Depreciation rate |

20% |

20% |

20% |

20% |

20% |

Depreciation expense |

$6,000 |

$6,000 |

$6,000 |

$6,000 |

$6,000 |

Accumulated depreciation |

$6,000 |

$12,000 |

$18,000 |

$24,000 |

$30,000 |

Written-down value |

$24,000 |

$18,000 |

$12,000 |

$6,000 |

$– |

Depreciating using the diminishing value method

With the diminishing value depreciation method, you calculate depreciation on the written-down value of the asset (also sometimes called the adjusted tax value). With this method, you get more depreciation in the first years of life of an asset than you do later on.

If I use the same forklift truck example (where the forklift costs $30,000 and I estimate its life to be five years), then I calculate the depreciation rate simply by dividing 150 by the useful life. So, 150 divided by 5 equals 30, and 30 per cent is my diminishing value depreciation rate.

Table 12-2 shows the decline in value of this forklift over the course of five years using this method.

|

Table 12-2 Claiming Depreciation Using the Diminishing Value Method |

|||||

Year 1 |

Year 2 |

Year 3 |

Year 4 |

Year 5 |

|

Cost price |

$30,000 |

||||

Opening written-down value |

$30,000 |

$21,000 |

$13,700 |

$10,290 |

$7,203 |

Depreciation rate |

30% |

30% |

30% |

30% |

30% |

Depreciation expense |

$9,000 |

$6,300 |

$4,410 |

$3,087 |

$2,161 |

Accumulated depreciation |

$9,000 |

$15,300 |

$19,710 |

$22,797 |

$24,958 |

Written-down value |

$21,000 |

$13,700 |

$10,290 |

$7,203 |

$5,042 |

Depreciating using asset pools

Rather than calculating depreciation on each asset individually (refer to preceding sections), the other method for depreciating assets is to pool assets together and depreciate the whole asset pool.

Asset pooling is allowed for Australian small businesses turning over less than $2 million per year, and accountants often prefer to use this method for calculating depreciation. For businesses with a turnover greater than $2 million per year, asset pooling is only allowed for assets that cost more than $100 and less than $1,000.

Working with an asset pool is a four-step process:

Calculate depreciation on the opening value of the pool.

At the time of writing, you calculate depreciation at a rate of 30 per cent for businesses with a turnover of $2 million of less.

Add the cost value of any assets acquired during the year to the value of the pool.

Depreciate any assets acquired during the year.

At the time of writing, this depreciation rate is 15 per cent for businesses with a turnover of $2 million of less.

Deduct any proceeds from the sale of assets from the total value of the pool.

This method is pretty straightforward to work with. For you as a bookkeeper, all you need to know is that you allocate both the receipt of money from the sale of assets as well as the expenditure from the purchase of assets to an asset account called General Business Pool. (This account may also be called Asset Pool, Fixed Asset Pool or something similar).

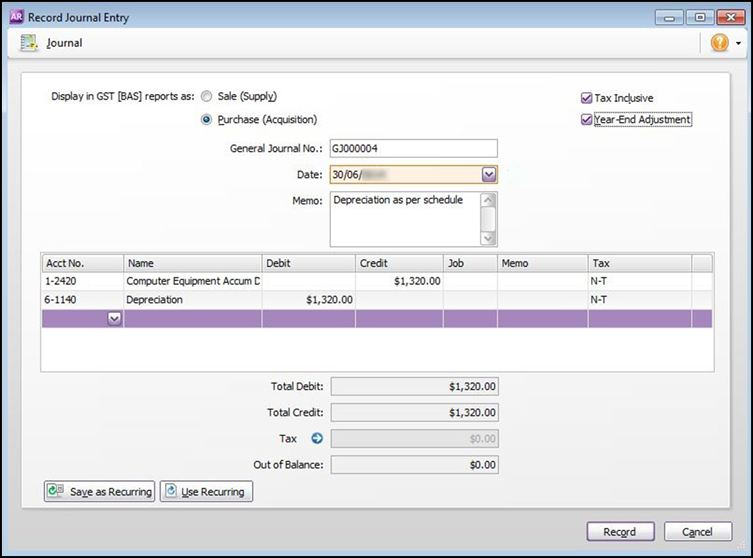

Recording depreciation

You record a journal for depreciation by debiting an expense account called Depreciation Expense and crediting an asset account called Accumulated Depreciation. (Alternatively, if your accountant pools assets when calculating depreciation, the journal may be to debit Depreciation Expense and credit an asset account called General Business Pool or something similar.) You can see what this journal looks like in Figure 12-9.

Figure 12-9: Recording a journal for depreciation.

Usually, either the bookkeeper or the accountant makes a journal for depreciation at the end of each financial year. However, if depreciation is a significant expense, I prefer to make some allowance for this expense throughout the year. This way, I can see the ‘true’ profit for a business and make realistic budgets for tax. Here’s what to do:

Find out how much depreciation expense was claimed last financial year.

Divide this depreciation expense by 12 to arrive at a monthly estimate for the current financial year.

Starting in the first month of the current financial year, create a monthly journal that debits depreciation expense, and credits accumulated depreciation.

Your journal is going to look just like Figure 12-9.

At the end of the year, calculate the exact amount of depreciation expense for the year.

Of course, the accountant may well be responsible for this calculation, rather than yourself.

Make one last journal adjustment, dated the last month of the financial year, for the difference in total depreciation.

For example, if you had claimed $10,500 in depreciation expense throughout the year, but the final calculation comes out at $10,000, then you make one last journal entry crediting depreciation for $500.

Checking your schedule

I mention earlier in this chapter that your accountant calculates depreciation in one of two different ways: Either asset pooling, or listing each asset separately on a deprecation schedule. If your accountant uses a schedule, I recommend that you spend some time reviewing this document and checking its accuracy.

A depreciation schedule, by the way, is the list of fixed assets that a business owns (vehicles, tools, computers and so on), with columns for original cost, date of purchase, depreciation for the current year and written-down value. You can usually find a copy of this schedule attached to the most recent end-of-year accounts, but if you can’t locate the schedule in this spot, simply ask the company accountant to send you a copy. Accountants always complete a depreciation schedule as part of doing the tax returns for a business.

If I’m in a pernickety kind of mood (which I am, more often than not), I like to check that the values in my depreciation schedule match up with the assets in my Balance Sheet. I do the following:

- I compare the original cost of every asset group in my schedule against the corresponding value in my Balance Sheet. For example, I compare the original cost column of computer equipment in my schedule against the account called Computer Equipment at Cost in my Balance Sheet.

- I compare the written-down value of every asset group in my schedule against the corresponding value in my Balance Sheet. The written-down value is the value of an asset after depreciation. To arrive at this value from my Balance Sheet, I deduct the total of my Computer Equipment Accumulated Depreciation account from my Computer Equipment at Cost account.

The last thing I do when reading through a depreciation schedule is to make sure that the schedule doesn’t include any assets that have long since departed from this earth. You know the kind of thing, ancient computers, antiquated phone systems and the like. If I spot an asset on the schedule that I know doesn’t exist any more, I simply let the company accountant know in time for next year’s tax return.

I’m not suggesting you spend hours figuring out how to value stock using these different methods. However, because different valuation methods yield such different results, I do suggest that if you’re setting up accounting or point-of-sale software and you have a choice as to inventory valuation methods, you seek advice from the company accountant before proceeding.

I’m not suggesting you spend hours figuring out how to value stock using these different methods. However, because different valuation methods yield such different results, I do suggest that if you’re setting up accounting or point-of-sale software and you have a choice as to inventory valuation methods, you seek advice from the company accountant before proceeding. I’ve done oodles of stocktakes over the years. The one I remember best was in a huge warehouse when the stocktake took about ten hours, with eight staff counting all day. Then the manager and I stayed up till 2 am, typing the counts into the computer one by one.

I’ve done oodles of stocktakes over the years. The one I remember best was in a huge warehouse when the stocktake took about ten hours, with eight staff counting all day. Then the manager and I stayed up till 2 am, typing the counts into the computer one by one.