Chapter 2

Creating a Framework

In This Chapter

![]() Finding a spot for every single transaction

Finding a spot for every single transaction

![]() Gathering materials with account classifications

Gathering materials with account classifications

![]() Building foundations for your Profit & Loss report

Building foundations for your Profit & Loss report

![]() Analysing income with a bird’s-eye view

Analysing income with a bird’s-eye view

![]() Making everything just right with Balance Sheet accounts

Making everything just right with Balance Sheet accounts

![]() The finished home — your first chart of accounts

The finished home — your first chart of accounts

If bookkeeping were just about doing your tax, the way you categorise information would be pretty simple. Income would be just one total, and most expenses would be lumped together, with only stuff like bank interest, rent and wages separated on reports.

However, your job as a bookkeeper is about much more than tax. You want to generate reports that explain exactly where your income comes from, which activities generate the most moolah, what the expenses are, how actual results compare against budgets, and lots more.

The way you categorise business transactions — in other words, the names of the accounts you use — provides the key to generating this kind of clued-up business reporting. Figuring out the accounts required takes a few smarts, because every business is unique and needs a custom-made list of accounts. But when complete, this list forms the framework for every business report.

In this chapter, I help you to build your own list of accounts. I wax lyrical about the differences between an asset and a liability, between income and expenses, and between earthlings and aliens. Discover how to set up a killer list of accounts that not only keeps the tax bigwigs happy, but helps this business flourish to boot.

Putting Everything in Its Place

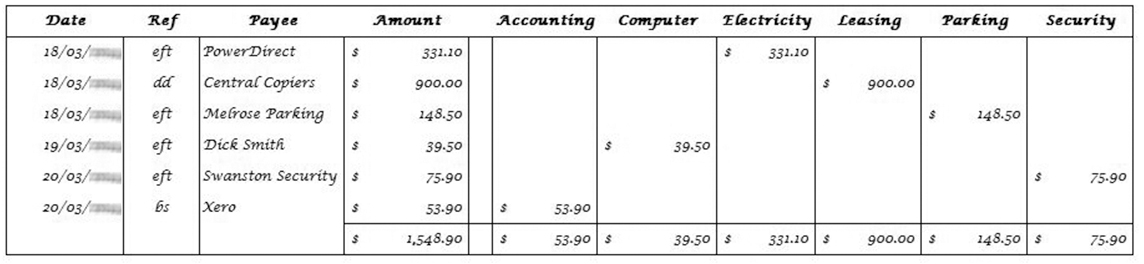

When I first worked as a bookkeeper, in the dim and distant past (but not before the dinosaurs, as my children claim), I worked with traditional handwritten ledgers. The cash disbursements ledger looked a little like Figure 2-1, with dates and amounts listed down the left side, and a series of columns all the way across, with a different column for each kind of expense.

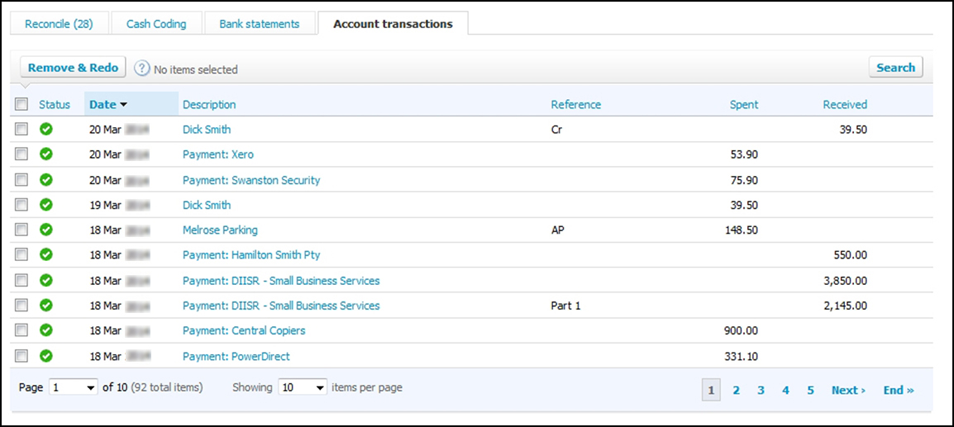

Regardless of how you do your books these days, the concept remains the same. If you work with a spreadsheet, chances are that your books look pretty similar to Figure 2-1. Even with accounting software, the core information remains constant. Figure 2-2 shows the same transactions in Xero, with a column for the date, a description, a reference number (when relevant), and the amount. (In Figure 2-2, Xero shows both incomings and outgoings for the selected bank account; in Figure 2-1, the spreadsheet shows outgoings only.)

Regardless of how you record transactions, the choice of account is crucial. In Figure 2-1, the accounts are the headings that run along the top of each column. In Figure 2-2, you need to click each transaction to view the details of which account the transaction has been allocated to.

Your job, as Bookkeeper-Chief-in-Command, is to decide exactly what these accounts should be. (After all, how can you record transactions if you don’t know where to put ’em?) The rest of this chapter gives lots of tips about how.

Figure 2-1: handwritten cash disbursements ledger.

Figure 2-2: An account transaction listing in Xero.

Classifying Accounts

A chart of accounts is the list of accounts to which you allocate transactions. These accounts describe what a business owns and what it owes, where money comes from and where money goes.

Accounts fall into six broad classifications:

- Assets: Things owned by the business, such as cash, money in bank accounts, computers, buildings and motor vehicles.

- Liabilities: The stuff that keeps people up at night, such as credit card debts, supplier accounts, tax owing and bank loans.

- Equity: The owner’s stake in the business, made up of money invested initially, or accumulated profit/loss built up over time.

- Income: Income, quite simply, is money generated from sales to customers or returns on investments.

- Cost of sales: What it costs in raw materials, supplies or production labour to make the goods sold.

- Expenses: Business overheads, such as advertising, bank charges, interest expense, rent or wages.

I explore each of these account classifications in much more detail later in this chapter, discussing what kinds of accounts typically belong under each one.

Building Your Profit & Loss Accounts

How you build your Profit & Loss accounts depends on what kind of system you’re using. If you’re working with a spreadsheet, the accounts are simply the headings of the columns where you list transactions. If you’re working with accounting software, you typically go to either your Accounts List (in MYOB) or your Chart of Accounts (in QuickBooks Online, Reckon or Xero).

Analysing income streams

Most businesses have more than one stream of income. Maybe you’re a builder who earns money from new houses, as well as renovations and extensions. Maybe you’re like me and earn money from a combination of journalism, consulting and teaching. Or maybe you’re a musician who also does a bit of teaching on the side.

As a bookkeeper, think about the different sources of income a business generates. If a business has fewer than five income accounts, have a think about how you could describe income in more detail. Each major source of income needs a separate income account. For example, my friend who is a builder divides income into four accounts: Bathroom Sales, Kitchen Sales, Tile Sales and Renovations. This way, he generates regular Profit & Loss reports that reflect how his business generates revenue.

Accountants also like to talk about other income or abnormal income. Other income or abnormal income includes any income that’s not really part of your everyday business, such as interest income, one-off capital gains or gifts from mysterious great-aunties. Other income gets reported separately at the bottom of a Profit & Loss report.

Separating cost of sales accounts

Whatever kind of business you have, you probably have some expenses that directly relate to sales. In accounting jargon, expenses that directly relate to sales are called variable expenses (also sometimes called direct costs or cost of goods sold). Expenses that don’t directly relate to sales are called fixed expenses (also sometimes called indirect costs or overheads).

This theory may seem all very well, but you need to understand how it applies in the context of your own business (or those you’re doing the books for). Here are some examples that may help:

- If you’re a manufacturer, variable costs are the materials you use in order to make things, such as raw materials and production labour.

- If you’re a retailer, your main variable cost is the costs of the goods you buy to resell to customers. Other variable costs, particularly for online retailers, may include packaging and postage.

- If you’re a service business, you may not have any variable costs, but possible variable costs include sales commissions, booking fees, equipment rental, guest consumables or employee/subcontract labour.

In contrast, fixed expenses are expenses that stay constant, regardless of whether your sales go up and down. Typical fixed expenses for your business may include accounting fees, bank fees, computer expenses, electricity, insurance, motor vehicles, rental, stationery and wages.

- Do you use raw materials to create new products? Examples could include ingredients, foods, timber, metals, paper or plastics.

- Do you purchase finished products or materials for resale? Examples could include a clothes shop that buys clothes, a cafe that buys coffee beans or a landscaper that buys soil and plants.

- Do you purchase any materials for packaging? Possible examples are bottles, bubble-wrap, caps, cardboard or envelopes.

- Do you use any energy as part of manufacturing items, such as electricity or gas in the factory?

- Do you employ any labour when manufacturing items, such as factory wages, subcontractor wages or production wages?

- Do you employ any labour for which you charge clients or customers directly? An example could include an electrical company that employs electrical contractors and charges customers by the hour for the contractors’ time.

- Do you pay any commissions on sales? Examples could include sales bonuses, sales commission, sales discounts or sales rebates.

- Do you have any expenses relating to importing goods from overseas? Examples include inwards shipping costs, customs fees or external storage costs.

- Do you have costs relating to distributing or shipping items? Examples could include couriers, outwards freight, warehouse rent or warehouse staff.

Cataloguing expenses

Expenses are the day-to-day running costs of your business and include things like advertising, bank fees and charges, computer consumables, electricity, motor vehicle, rent, telephone and administration wages. Accountants also sometimes refer to expenses as overheads.

Here are some expenses I usually include in a list of accounts:

- Accounting Fees: I keep accounting fees separate from contract bookkeeping fees, so I can easily monitor what each service costs a business.

- Bank Fees: Use this account for the regular transaction fees you get on your bank account. If you get charged merchant fees — which you will do if customers pay by credit card — you need a separate account for merchant fees.

- Computer Expenses: I dump expenses for stuff like CDs, USB flash drives, incidental software and printer ink into this account. I also often create additional expense accounts for Internet Expense and/or Website Maintenance.

- Dues & Subscriptions: Here’s the spot for licence fees, professional memberships, magazine subscriptions and similar items.

- Electricity & Gas: This is where you can catalogue your personal contribution to climate change.

- Home Office Expenses: If a business operates from home, you may include expenses such as electricity, mortgage interest, rates and repairs in this account. (However, check with the accountant first regarding what home office expenses can be claimed.)

Insurance: If you have hefty insurance bills, I suggest you create a header account called Insurance Expense and, underneath, create detail or subaccounts for different kinds of insurance, such as Building and Contents Insurance or Public Liability Insurance.

I usually tuck the insurance for vehicles under the Motor Vehicles header, rather than the Insurance header, because when you report for tax, you need to report separately for motor vehicle expenses.

I usually tuck the insurance for vehicles under the Motor Vehicles header, rather than the Insurance header, because when you report for tax, you need to report separately for motor vehicle expenses.- Interest Expense: Don’t get muddled between bank charges and interest. Bank statements always differentiate clearly between the two; all you have to do is be alert to the difference.

- Motor Vehicle Expense: Again, maybe make a header account called Motor Vehicle Expense and, underneath, create subaccounts for fuel, maintenance, registration and so on.

- Office Expense: You can use this account for squillions of different things, from printing and stationery to paper and pens, from a new office chair to a new filing cabinet. Just make sure you’re clear about the distinction between an expense and an asset — see Chapter 12 for more about this topic.

- Rent Expense: Unless you work out of a home office, you almost certainly pay rent on an office or factory.

Salaries & Wages: If you have more than a handful of employees, consider creating detail accounts or subaccounts for the different categories of employees (see the sidebar ‘Under the microscope’ later in the chapter). For example, a restaurant may have three accounts: One account for kitchen staff, another for front-of-house staff and another for management.

Salaries & Wages: If you have more than a handful of employees, consider creating detail accounts or subaccounts for the different categories of employees (see the sidebar ‘Under the microscope’ later in the chapter). For example, a restaurant may have three accounts: One account for kitchen staff, another for front-of-house staff and another for management.- Superannuation: In Australia, I suggest you create two superannuation expense accounts: One for employees and one for directors or business owners. In New Zealand, you need only one expense account for super, usually called KiwiSaver — Employer Contribution.

- Telephone: If telephone expenses are high, create two accounts: One for office phone and the other for mobile phone.

Travel & Entertainment: When accounting for travel expenses, remember to separate domestic and overseas travel into separate expense accounts. When accounting for any entertainment expenses, always separate these expenses from other travel expenses. (Entertainment expenses are tricky in terms of tax, and the accountant will need to review these transactions in order to check that they are tax-deductible.)

Travel & Entertainment: When accounting for travel expenses, remember to separate domestic and overseas travel into separate expense accounts. When accounting for any entertainment expenses, always separate these expenses from other travel expenses. (Entertainment expenses are tricky in terms of tax, and the accountant will need to review these transactions in order to check that they are tax-deductible.)

By the way, accountants sometimes also use other expenses as an additional account classification. Other expenses are abnormal expenses that aren’t part of your everyday business, such as lawsuit expenses, capital losses or entertaining aliens from outer space.

Dealing with personal expenses

Wondering what to do about personal expenses, where the owner takes money out of the business account and uses this money for something personal? You don’t show these transactions as expenses, because personal transactions aren’t expenses of the business. Here’s what to do:

- If you’re doing the books for a sole trader, allocate personal spending to an equity account called Owner’s Drawings.

- If you’re doing the books for a partnership, allocate personal spending to an equity account called Partners’ Drawings (you may need to create a separate drawings account for each partner).

- If you’re doing the books for a company, either allocate personal spending to Director’s Wages (in which case you need to allow for wages and superannuation), or allocate personal spending to a liability account called Director’s Loan (in Australia) or Shareholder’s Loan or Shareholder’s Current Account (in New Zealand).

Seeing Where the Money’s Made

Some businesses are actually several businesses bundled under the one name — like the newsagent who doubles as a post office and dry-cleaning agency, or the handyman who fixes your cupboard doors and also mows the lawn. To use accounting jargon, some businesses have multiple cost centres.

By the way, don’t be tempted to create a swag of new accounts with a separate set for each cost centre. Instead, use a single set of accounts, but take advantage of the cost centre reporting in your accounting software. In most versions of MYOB, you have two ways to report on cost centres: jobs and categories. Jobs are the most versatile feature, because you can allocate a single transaction to more than one job. Categories work better if you have separate bank accounts for each cost centre, or separate physical locations, or branches. Sometimes it works best to use both jobs and categories. For example, an architect client of mine has an office in Brisbane and another in Sydney. He uses the category feature in MYOB to identify which office transactions belong to, but he still uses the jobs feature to track profitability on each different project.

In QuickBooks Online and Reckon, you can report by cost centre using the Customer/Job feature or the class tracking feature. Generally, the job feature works best for individual projects and class tracking works best for different company divisions. For example, builders often use the Customer/Job feature to keep track of profit on individual jobs, but use class tracking to categorise these jobs, separating new houses, project homes and home renovations into different classes.

In Xero, cost centre reporting is more limited, with a simple category tracking feature. (The feature itself works just fine, but the limitations lie more in the restricted range of tracking reports.)

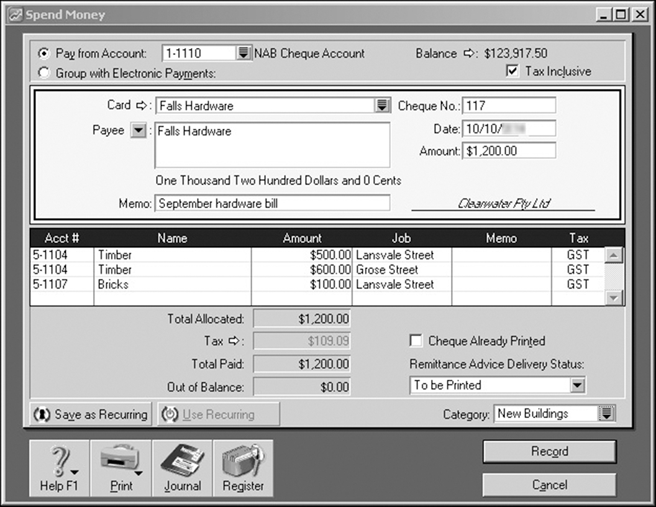

Whichever accounting software you use, the principle remains the same. You don’t just allocate a single transaction to an account, but you allocate it in other ways also. For example, in the screenshot in Figure 2-3, the transaction is allocated in several different ways: The Card field shows the name of the supplier, the Acct # column shows the type of expense, the Job column shows the projects, and the Category field shows the branch of the business that incurred the expense.

Figure 2-3: Accounting for cost centres by using both account codes and job codes.

Itemising Balance Sheet Accounts

If a business is already up and running, and has already completed the first year of business, an easy way to see what Balance Sheet accounts are required is to get your hands on last year’s Balance Sheet report from the accountant.

If a business is new, you can simply create new Balance Sheet accounts as and when you need them. However, read through the next few pages to get an idea of what accounts you may need to get you started.

Adding up the assets (ah, joy of joys)

So what’s an asset? Is it your pearly white teeth, your fine singing voice or your generous nature? None of these things, I’m afraid. The International Accounting Standards Board defines an asset as ‘a resource controlled by the enterprise as a result of past events and from which future economic benefits are expected to flow to the enterprise’.

Hmmm. My mind goes to mush when faced with this kind of talk, so I’m going to put it more simply: Assets are the good stuff, including anything you own, such as computers, office equipment, motor vehicles and cash.

Accountants like to classify assets according to how readily these assets can be converted into cash, typically using the headings current assets, non-current assets (also called fixed assets) and intangible assets.

Current assets

A current asset is anything that a business owns that can realistically be converted into cash within the next 12 months.

The kinds of things that get lumped into current assets include

- Bank accounts and cash: Accounts that fall into this account type include petty cash, cheque accounts, savings accounts and term deposits.

- Short-term investments: No, I’m not talking about your latest love. I’m thinking of nerdy stuff such as shares or unit trust holdings.

- Accounts receivable: Accounts receivable is the bookkeeping term for money that customers owe you. (Accountants sometimes refer to this account as trade debtors.)

- Inventory: Another old-fashioned bookkeeping term, inventory is the word bookkeepers use for stock or raw materials that get sold to customers or assembled to make goods.

- Prepayments: Smaller businesses don’t usually account for prepayments, but larger businesses make adjustments for things such as prepaid insurance, rent in advance or deposits paid to suppliers.

- Work in progress: Work in progress includes jobs that have started but aren’t yet complete.

Non-current assets

This classification (also sometimes known as fixed assets) is for anything physical that you can touch, feel and see, but that isn’t readily converted to cash. Sounds kind of sensual but I’m talking about relatively mundane things such as office equipment, land and buildings, computers and motor vehicles.

- Land and buildings: If a business buys a block of land or a building, this is the account to choose.

- Plant and equipment: Completely unrelated to potting mix, this rather agricultural sounding account includes stuff like new computers, telephone systems, machinery and tools.

- Motor vehicles: Yep, that banged up rusty old heap is actually an asset, not a liability.

- Accumulated depreciation: Yet another weird expression, meaning the amount the accountant has already claimed back on assets. I talk more about the convoluted workings of depreciation in Chapter 12.

Intangible assets

An intangible asset is something that is worth something, but that you can’t touch, smell or see. Intangible assets are usually not readily convertible into cash. (My husband assures me that his sense of humour is one of his intangible assets. At times, however, I reckon it’s more of a liability.)

The most common intangible assets are formation expenses, franchise ownership, goodwill and trademarks:

- Formation expenses usually relate to the cost of setting up a company. Because formation expenses aren’t tax-deductible, some accountants choose to show these expenses as an asset. (Other accountants write off formation expenses straightaway, and make a tax adjustment in the final return.)

- Franchise ownership expenses relate to the costs of purchasing and setting up a franchise.

- Goodwill is usually the purchase price of a business, or the price placed on the worth of a business. Many businesses don’t put a value on goodwill until they sell the business to someone else. At that point, goodwill becomes part of the purchase price and shows up on the Balance Sheet as an intangible asset.

- Trademark expenses are the costs of developing and registering a trademark (typically a business logo or name).

Listing liabilities (oh, woe is me)

Liabilities are the stuff that keeps you awake at night. You know, bulging credit card accounts, supplier bills, GST owing, hideous bank loans and that unmentionable loan from your parents-in-law.

In the same way as accountants like to bundle assets into groups, they do the same with liabilities.

Current liabilities

A current liability is an amount owed by the business which is due within a one-year period. The kinds of accounts that sit under current liabilities include

- Credit cards: I recommend bookkeepers think of credit cards in the same way as any other bank account. It’s just that the business owes the bank money, rather than the other way around. Strangely enough, simply ignoring credit cards and pretending they don’t exist doesn’t seem to work as a strategy.

- Overdrafts: Again, you treat an overdraft in the same way as a regular bank account.

- Accounts payable: Accounts payable (also called trade creditors) is the term for money that you owe to suppliers.

- Other current liabilities: This category covers any other liabilities that are relatively short term, such as customer deposits, employee wages, tax owing, GST owing or short-term director loans.

Non-current liabilities

A non-current liability is anything you owe that isn’t due to be paid out within the next 12 months. The kinds of accounts that sit under non-current liabilities include

- Hire purchase debts: Hire purchase debts are usually non-current liabilities because they’re payable over several years (although some accountants prefer to split hire purchase debts into current and non-current liabilities). Hire purchase liability accounts come complete with a partner, a strange account that goes by the name ‘Unexpired Interest Charges’ or ‘Future HP Interest Charges’. For more about this topic, check out Chapter 13.

- Bank loans or mortgages: You know what these are. Seems that banks are always in on the act.

Accounting for equity

Equity is a fancy term for the ‘interest’ that a director or an owner has in the business, including both capital contributed and the profit or loss built up over time. The kind of equity accounts you need when bookkeeping depend on whether the business has a sole trader, partnership or company structure.

Out on your own (sole trader accounts)

Sole trader equity accounts include Owner’s Capital, Current Year’s Profits and Owner’s Drawings. As a bookkeeper, the only equity accounts you allocate transactions to are Owner’s Drawings, which is the account where you allocate any personal spending by the owner, and Owner’s Contributions, where you allocate personal contributions from the owner.

Takes two to tango (partnerships)

With a partnership, each partner has both a Partner’s Capital account and a Partner’s Drawings account. At the end of each year, the accountant also uses a Distribution of Profit account for each partner. (The Partner Capital accounts, when added together, are equivalent to Retained Earnings in a company.)

Although partnerships don’t require an account called Retained Earnings, if you’re working with accounting software, you usually find this account is a default account that you can’t delete (at the end of each financial year, Current Year’s Earnings ‘roll over’ into this Retained Earnings account). You can rename this account to become one of the Partner’s Capital accounts. The accountant can then provide a journal at the end of each year that adjusts the partnership capital accounts.

Aiming high (companies and trusts)

Companies typically have Retained Earnings, Current Year’s Earnings, Dividends Paid and Shareholder Capital as the equity accounts. Occasionally, companies also have reserve accounts, such as an Asset Revaluation Reserve.

Retained earnings are the income that a company holds onto, and doesn’t distribute to shareholders. Retained earnings (or losses) are cumulative, building up from one year to the next. When shareholders receive a profit distribution, you allocate this payment to an equity account called Dividends Paid.

Trusts have a similar equity account structure to companies, but have an account called Issued Ordinary Units or Trust Equity instead of Share Capital. When trust beneficiaries receive a profit distribution, you allocate this payment to an equity account called Trust Distributions Paid.

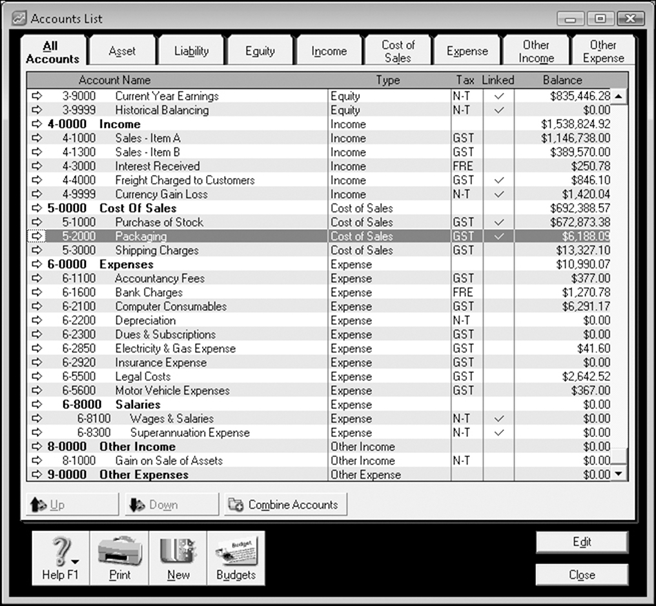

Building a Final Chart of Accounts

In Figure 2-4, you can see some of the accounts that make up the final chart of accounts for a wholesale business. The format of this chart of accounts is typical (listing account name, type, balance and so on), but remember that just as every business is unique, so every chart of accounts is unique also.

Figure 2-4: Some of the accounts that form part of a final chart of accounts, ready for action.

As a bookkeeper, make sure you tailor the expense accounts to the business concerned. On the one hand, you don’t want to create too many accounts (I once saw a chart of accounts that used a different expense account for every employee, and with over 25 employees this became ridiculous). On the other hand, if a business has a particular expense that makes up a large proportion of its expenditure, additional analysis can help.

As a bookkeeper, make sure you tailor the expense accounts to the business concerned. On the one hand, you don’t want to create too many accounts (I once saw a chart of accounts that used a different expense account for every employee, and with over 25 employees this became ridiculous). On the other hand, if a business has a particular expense that makes up a large proportion of its expenditure, additional analysis can help. Avoid using nondescript accounts such as Miscellaneous Expenses, Other Expenses or Sundry Expenses for expenses that are part of your everyday business. All this kind of account does is create work for your accountant at tax time, as your accountant will be obliged to scrutinise every transaction in a miscellaneous account in order to reallocate these transactions correctly.

Avoid using nondescript accounts such as Miscellaneous Expenses, Other Expenses or Sundry Expenses for expenses that are part of your everyday business. All this kind of account does is create work for your accountant at tax time, as your accountant will be obliged to scrutinise every transaction in a miscellaneous account in order to reallocate these transactions correctly. A chart of accounts as long as your arm

A chart of accounts as long as your arm I often get asked, ‘When is something an asset and when is something an expense?’ For example, how would you categorise the purchase of a new coffee machine for the office, a new swivel chair or a set of new blinds? The answer to this question depends on the current tax legislation, which varies according to the size of your business and whether you’re based in Australia or New Zealand. For more info on this enthralling topic, skip ahead to

I often get asked, ‘When is something an asset and when is something an expense?’ For example, how would you categorise the purchase of a new coffee machine for the office, a new swivel chair or a set of new blinds? The answer to this question depends on the current tax legislation, which varies according to the size of your business and whether you’re based in Australia or New Zealand. For more info on this enthralling topic, skip ahead to