CHAPTER 5

Business Resiliency: Common Transformations Along the Path

While previous generations of dynastic multigenerational families might have faced an environment of stability and continuity, the journeys described by our contemporary generative families were far more complex and eventful. By the third generation, no contemporary family enterprise remains as it was a generation before. The business expands into new markets and products. It may go public or add other shareholders. Or perhaps the legacy business is sold and the family diversifies. New family members are born, grow up, or marry into the family, and they bring different values, skills, and interests. One constant hallmark of the generative family is its resilience, the ability to adapt and change, in response to either success or adversity.

Over nearly one hundred years, each family in this study has been through major transformations. Some have become diversified, migrating into other areas by modifying or expanding their portfolio of products and services. A business that old has faced multiple setbacks and crises; some even faced bankruptcy. In an enduring family enterprise, crises lead to adaptation, rethinking of how they work and exploration of new paths ahead.

The social, business, and cultural environment is changing, as a new global, digital world unfolds. The extent of change posed by new communication technology, globalization, environmental destruction, and instability of global commerce threatens the survival of even the most successful enterprises. Each new generation exhibits diverging expectations, needs, and dreams as their family creatively responds to the predictable crises that arise.

In each generation, the business is endangered. It can fail or be sold, and the family can choose to disperse into separate households. Generative families keep deciding again and again that they want to take up the deep challenges to stay together and adapt. To succeed, they must question traditions and challenge long-standing cultural traditions to sustain family closeness in an increasingly impersonal world.

This chapter outlines the evolutionary path of generative families. It introduces the common challenges of family and business growth and development emerging in each generation and looks at how generative families manage the increasing complexity of creating a strong family connected to a thriving family enterprise.

Surviving a Crisis

After a generation or more of success, every business faces crises: new technology, business recessions, increasing competition, or the need for reinvestment capital can challenge the business. Here are two examples:

- After surviving a world war and occupation, one family found itself once again in a country where it was unwelcome. Three G3 cousins pooled their considerable skills in international trade, and each moved to a different country. Like the Rothschilds, these cousins ended up creating three new businesses, all of which grew and thrived far beyond the scope of their original business.

- After three generations of success with an iconic product, another family business saw that new technology was making its product obsolete. But the company had tremendous recognition and affection. After business school and apprenticeship at a consulting firm, a third-generation family leader was asked to come aboard and redefine the business. After exploring people's perceptions of the company and its products, the family came up with a new mission that led it in new directions but with a continued focus on consumer goods. Its reputation gave it visibility while the new leader moved manufacturing offshore and created a new generation of products. He helped employees displaced by the transition find new jobs and rebuilt the obsolete factory as a product development center. The company successfully leveraged its legacy of brand recognition to a new generation of customers and products.

Internal and external challenges trigger the need for the family enterprise to adapt and change, sometimes in major ways. Common “triggers” that lead the family to reevaluate and transform business policies and practices include the following:

- A sudden death highlights lack of a qualified successor inside or outside the family.

- New technology leads to new competitors and need to reinvest.

- With more shareholders and a maturing business, a sudden or gradual decline in profit moves the family to pay attention.

- If the business is doing well, the family faces offers to buy it.

- As the business generates profits, the family extends and diversifies into other investments or business ventures.

- Generational transitions bring more shareholders to the table and sometimes add new professionals who challenge the management of a break-even business.

- Inevitably some family members want to sell their shares, and the other shareholders must face the questions of whether to buy them out and how to value the company.

In our globally connected world, deep changes occur ever more rapidly. One seventh-generation family leader observed that for six generations, things were predictable and orderly. The business passed from first son to first son, with the business operating in the same way with skilled craftsmen and laborers. During the past twenty years, however, the family experienced more change than all previous generations combined. The business environment became global, technology transformed, and competition emerged everywhere. Internally, the family decided that all family members—sons and daughters, younger and older—were eligible for leadership positions, not just the number-1 son.

Families, however, are designed to strongly resist change. They strive toward providing security, predictability, and stability. Many business founders and leaders want things simply to continue unchanged because they have known nothing but success. They avoid and deny anything that suggests their old ways have to change. Many business families fail because they are unable to retain the spark of creativity that could create value for the new generation. In these cases, businesses may become stale and vulnerable. Conflict may erupt, calling the direction and leadership into question. Family members worry about how they can avoid decline.

As business elders live longer, they want to enjoy their success and grow weary of having to reinvent themselves. Indeed, a core aspect of the ability to change is skill in deciding when to “harvest” the value of a family asset by its sale. This can free the family to pursue new opportunities as new generations, with different perspectives, emerge. It can also free the family so that the second generation can “rescue” the family by taking it in a new direction. Each generation has the opportunity to reinvent the family enterprise. This chapter presents the most common transformations experienced by generative families and how they actively prepare for them.

Continual Reinvention

What does it take to sustain continual business innovation and adaptation? Resilient businesses approach a turbulent environment by anticipating and adapting rather than reacting.

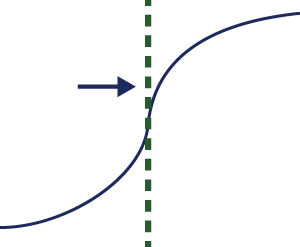

A common model for the growth and development of a business is the S-curve. A founder with limited resources struggles to build a successful business, and the business then takes off in a spurt of exponential growth. But growth cannot continue forever. The curve eventually levels off or declines as products mature, competition emerges, or technology and tastes change. The business now faces a crisis and must find a new pathway to growth or face decline. A family enterprise experiences periods of exponential growth, but its continued success rides on the family's ability to renew itself when growth slows or crisis strikes. (See Figure 5.1.)

Figure 5.1 An S-curve.

Figure 5.2 Addition of a new S-curve.

A generative family seeks opportunities to create new S-curves or extend current ones. It jumps from a maturing or declining effort into the development of new products or markets or a new venture or investment. Prospects for change depend on where you are on the S-curve; this is not always apparent. When the family undertakes a deep transformation in its business, the family potentially enters a new S-curve. (See Figure 5.2.)

Few generations begin and end with the same business in the same place. Enterprises face external threats like social media, global competition for core products, new brands, aftermath of war and political threats, or maturing and obsolete products. Businesses can't wait too long; they have to anticipate and respond to challenges. If the family's only asset is a single business, the threat is especially severe. The old leaders are mortal; they must find innovators within the family who have the will and the skill not just to sustain their vision but to adapt and change.

Our research allows us to look back on the journey over three or more generations of each generative family. We can envision a timeline outlining the twists and turns of such a family's journey across generations. A family can create a personal version of Figure 5.3 to remember and connect the sequence of key events in their history. This is one way that the family educates and inspires the younger generation about the family story.

Innovation and entrepreneurship are not the sole province of the founding generation. Generative families develop family talent to redefine themselves in each new generation. They experience a continual tension between maintaining the status quo, “harvesting” wealth, and investing in innovation for the long term. The family has to deal with dissent and agree on a direction; generative families accomplish this successfully.

They buy, sell, innovate, and renew while continually redesigning their business. As Chapter 6 will show, they can do this as “craftsmen” by innovating their core product or technology or as “opportunists” by seeking out new business directions or ventures.

Figure 5.3 Timeline of key events in the family journey.

The change capability of generative families is often due to the initiative of their rising generation. The young successors are not satisfied with accepting the status quo, as lucrative as that may be. They are anxious to prove themselves and excited about new directions. Their global education has taught them new ideas and possibilities, but to put their skills and knowledge to the service of the family, they need support from their elders. The rising generation needs to listen and learn from the elders' wisdom and experience before charging off in a new direction.

Turning Points: Four Major Transformations of Generative Families

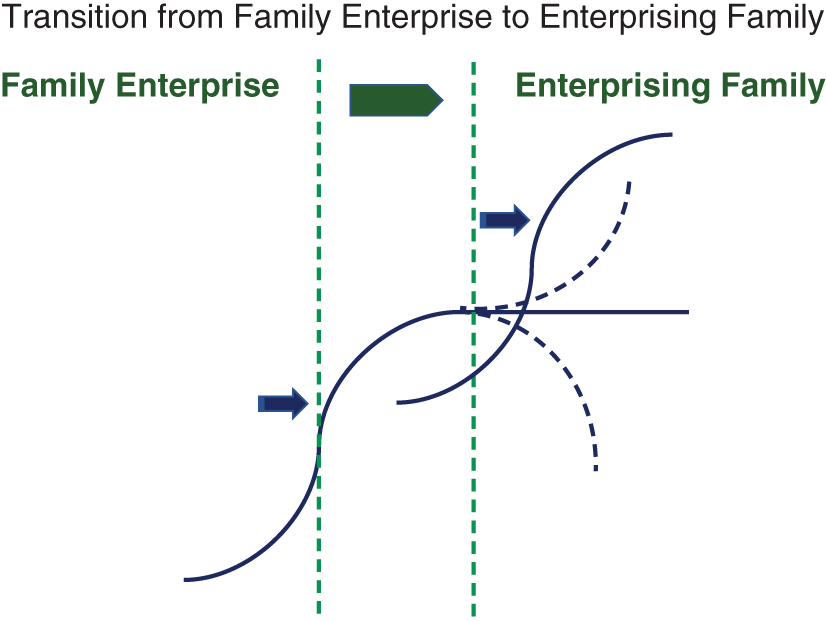

A majority of the generative families interviewed for this study move along a path punctuated by four huge milestone transformations:

- Harvesting the legacy business by a sale or other event that accesses liquidity

- Pruning the family tree by buying out some family members, leaving only those committed to business ownership

- Diversifying by buying other businesses and making other investments, thus creating a business portfolio

- Grounding by creating a family office to centralize and oversee the multiple business entities and operations, and continue the family identity.

Each of these transformations deeply changes the nature of the family. The generative family emerges from each of these major transformations with a new focus that continues its legacy values and builds upon family strengths. The family works actively through the resilience cycle to anticipate, redefine itself, and work through changes. While families do not go through these milestones in strict order, the progression from single-family business with a few owners to a portfolio of enterprises with a family office and a pruned (but still sizable) set of family owners defines the path of most of the generative families featured in this book. (See Figure 5.4.)

Figure 5.4 Evolution of the family enterprise.

“Harvesting” the Legacy Business: Liquidity Offers New Opportunities1

When a wealth creator tells future generations, “Never sell the family business,” the heirs are wise to take this admonition with a grain of salt. No business can last forever. A business-owning family should not wait for its business to fail. Instead, it looks ahead and periodically asks:

- Does this business make sense for us now?

- Can we remain competitive in the face of new technology, globalization, and social change?

- Can we handle and operate the business as it should be managed?

- Do we have the resources to invest in sustaining excellence?

Most families wanted to hold onto their legacy businesses. But sometimes, even a strong and vibrant business can be threatened by external factors like social changes or new technology. One family, reluctantly and with great reservations, decided to sell its legacy business. A senior member of the family related:

Nobody wanted to sell the company, but because we were offered a premium that was 67 percent higher than the day before, we felt we had to take the offer. We realized that if we turned down the offer, we'd have to allocate significant resources to rebuild the company, and this would involve major changes in leadership. We weren't sure whether we could persevere through the turmoil this would cause, so we ultimately decided to sell.

Some studies imply that the sale of the legacy business means the end of the family as an organized entity. Our research found, however, that this is far from the case. The sale of the legacy business is a major transformation—a watershed event—but it leads generative families to a new beginning. Selling a business means transferring value for money and leaving the business behind. The term “harvest” refers to a family's departure from majority ownership of its legacy business because, for the family, the event is not an end. In agriculture, a harvest allows the field to regenerate and then be replanted. A family that harvests decides to take resources from a single business to nurture and develop other opportunities. The sale of assets can occur more than once; a few families report that they harvest a major asset every generation to offer some family members the chance to go out on their own and take on new challenges. The new reality can also be traumatic for a generative family. It can mean the loss of family identity that was embodied in the business and its place in the community, and entry into unfamiliar territory.

Half of the families in this study “harvested” their legacy business. This has two transformative effects on the family:

- It allows some family members to cash out and leave the family partnership. Other family members choose to support their lives and individual family needs by remaining in the family partnership. Selling an asset is like letting pressure out of a pump; it allows the family to continue to operate while reducing pressure for continual returns on their invested assets.

- It allows the new generation to develop new ventures that employ their skills and meet the family's need for new sources of wealth. Several families had more than one major family business. By selling one of their assets that either needed new capital or was bringing slower and less predictable returns, they were able to refocus on new efforts and investments.

As a result of the harvest, the families in this study commonly develop several sources of wealth—a holding company, family office, or perhaps a private trust company that combines the benefits of a family office with that of a trust. Any of these arrangements enable them to buy and sell investments.

Even though the family may value its legacy business highly, there may be good reasons to harvest. While the business performed well in the past, it may be maturing, producing lower returns, or needing a significant infusion of capital. The enterprise may have grown to enormous proportions but attracted few family members to manage it. In cases like these, a family often feels comfortable detaching its identity from the business. Even though there may be sentimental ties to the business, the family may decide to move on, to find a new source of identity and outlet for its energy.

Who makes this decision, and how is it made? In most family businesses, the decision is made by only a few family members at the ownership or board level. They may not share an offer within the family because of confidentiality, or they may not feel the need to inform the family at all. We see a different process of decision-making in generative families. Board members or key shareholders might make informed decisions, but they understand that due to the emotional significance of the proposed sale and the values of the family, nonowning family members should be consulted, too. Members of the younger generation, who stand to become owners in the future, are especially important. Do they understand and agree with the values and challenges that are being considered in the sale? They are the ones who will lose an opportunity because of the sale. The generative family finds a way to engage the whole family in the conversation about the possible sale and solicits opinions before taking action.

Sometimes, upon listening to the voices of its members, a family may decide against a sale. Instead, it recommits the family's energy and resources to renewing the business. Here are three examples:

- The challenge at this point was to bring in a nonfamily CEO. But we questioned whether he or she would be able to maintain the culture and the values that we have established. We have a very strong culture that is part of the fabric of our company. Part of our sadness about selling the business came from the feeling that we might lose this wonderful legacy and culture we've developed.

- There has always been a strong commitment to the long-term ownership of the business. We've been approached countless times, even monthly, by venture capitalists or competitors who want to buy the business, but we've never even discussed these offers at the board level because the family has made our policy clear. We simply say, “We're not interested,” and move along. We have a commitment to maintaining the business for future generations.

- If all the assets of the business were liquidated, everyone would have a bunch of money in their pockets. But we would just feel sick, like we let down our ancestors who built the business and never thought of selling it.

Deciding to Sell

Despite the central role of the legacy business in sustaining family connection and identity, there may be business reasons to consider a sale, as this G3 leader observed:

By the time the question came up about whether to sell the business, the family members were pretty distanced from the business. Most of them have professions, so the business is always in the background. That represented the culture of the family when we decided to sell. That decision was actually initiated by nonfamily, nonexecutive directors who said, “You've had an amazing ninety-year run, but now you're running a lot of risk. We're worried about the risk you're carrying as a family.”

If they are not committed to the business, minority family owners can force a sale.

They had an empire—all the land around the city center. But ultimately, they had to sell because the small shareholders wanted to sell. Often the small shareholders are unhappy and turn sour. And when someone turns sour, they start to act badly.

If the family does not have the will, skills, or resources to address emerging business needs, it can preempt a later crisis by a strategic choice to sell and diversify. For example, one family controlled a large but poorly performing public company. Content with their considerable dividends, they did not demand change until performance worsened and threatened the dividend. The family was approached by a buyer who wanted to take the company in a different direction than the family wanted. Nevertheless, given the decline that had not been addressed, the family felt it had to sell. Because it was a public company, the deal was much in the news, and this made the very private family uncomfortable. Family members were glad to descend back under the radar after the sale was consummated.

It's important to note that family advisors may become a separate interest group of their own and that their own self-interest may further complicate, or even undermine, the situation. The following family eventually sold because it lost connection to and trust in the business:

We had limited input to a trustee office that organized things for us. We should have learned twenty years before that we needed a more robust structure. Our advisors told us that they could provide that structure, but this didn't build family leadership because we weren't a part of that structure. Communication within the family wasn't robust and there wasn't a clear way of pulling it together. When the possibility of a sale came up, there was an attempt to improve communication and empower the family. But the advisors felt that their power was threatened by the sale. They were always worried about what was going to happen to them instead of working for the best interests of the family.

A sale transports the family in a new direction that it must address and adjust to:

For a long time, our family got together because we were all connected to the company. We would meet with our advisors four times a year and meet with the company twice a year. Family board members met monthly with the board, and we had a lot of family meetings around that. We would also attend reunions, weddings, and funerals. We saw a lot of the family collectively. After the sale, we realized how important the business had been in holding us together. We try to meet quarterly, but we don't have that same glue that holds us together. It's very difficult to create new things for our meetings.

As the following sections will show, after the harvest there is a critical period to rebuild family partnership and reconsider whether the family will recommit to new shared investments or enterprises. For many families, the business sale does mark the end of the family as an organized, shared enterprise. For the generative family, it marks a turning point to a more diverse and creative future together.

“Pruning” the Family Tree: Becoming a Family of Affinity

As new members enter the family by birth and marriage, the challenge of sustaining commitment to long-term goals while sacrificing shorter-term profit distributions reemerges as each new shareholder seeks a good return from his or her asset.

These changes do not come without pain. Often, families have to reinvest profits, which cuts down on the short-term returns to family members, who may not be patient or supportive. As a result, all the families in this study have faced the choice of pruning the family tree by buying out a branch or member who does not want to reinvest. Each family has a “liquidity event,” buy-out process, or distribution, whereby members have the opportunity to redecide whether or not to remain partners.

If a family member lives far away, does not feel excited to be part of a community of second and third cousins, or wants access to capital to spend or invest in a different direction, he or she may choose to leave.

Remaining entails responsibilities that some family members do not want to take on:

- Commitment of time and energy to governance—both oversight of the business and participation in shared family activities

- Spending time and working with other family members

- Willingness to forgo short-term profits and income for long-term investments

As the number of family owners increases, each shareholder holds a smaller share, making it more difficult to achieve alignment and shared goals. The families in this study adopted redemption policies that allow smaller family owners to sell their shares either back to the company or to other family members. All the families in this study have adopted exit policies as part of their family shareholder agreements; these policies are necessary safety valves to avoid tension around differences and destructive conflict.

Different branches develop divergent interests. Some look at their business portfolio and decide to separate a long-term business with moderate risk from riskier entrepreneurial ventures. To others, owning a larger part of a smaller business can be more attractive than a small share of a larger one. Such horse trading occurs in most of the families in this study; the development of a fair and clearly defined internal family marketplace for shareholders can sustain family ownership while allowing individuation.

It makes a big difference if the parting is natural and friendly rather than the result of conflict and disagreement. Many generative families report natural events where the family divides in a way that does not disrupt their family relationships:

When the family broke up in generation two and generation three, it wasn't a breakup. It was an amicable, “Let's live together but not have a marriage certificate.” You know, “Let's get along with our cousins or our uncles” or whatever it is, “and have a very good relationship in the family” because family is first.

In the third or fourth generation, some families divide their partnership by branches. When a family is so hugely successful that it owns multiple businesses or reaches a size where integration or synergy is a challenge, it may be adaptive for the family to separate branches. Several large families have gone in that direction; one member stated that it was the “village tradition” to go in separate directions as they split into several loosely connected branch portfolios. In some family traditions, the parents divide resources into separate packages for each of their children.2 While they may miss the chance to build on a greater scale, they have their own forms of success as each family member is able to create his or her own unique destiny.

However, such arrangements need to be carefully planned. By allowing owners to exit, the family postpones the geometric rise in number and dilution of share ownership. That is why many generative businesses have a relatively small number of shareholders. Those who remain are willing to forestall current profits for longer-term goals.

Upon the sale of a legacy asset—a liquidity event—each family member has a choice. One option is to go his or her own way with the new liquid capital. Alternatively, some family members might continue to invest together by forming an investment group or family office. For example, after the sale of their huge legacy business, the largest of three family branches chose to continue as an investment group:

The decision to separate into three branches was organic. We'd been talking about it for a long time. The sale moved us in that direction without needing a referendum. We took a good amount of time to figure it all out. We talked to other families who have gone through similar stuff and to a lot of advisors about our options.

After the sale, family members could decide to go off on their own. This was complicated, however, because the ownership was in the trust. Ultimately, we decided to continue the trust together with new advisors and trustees. Family members had the choice to place their assets in our investment partnership.

At this point, family members began to have access to stock. We have redemption policies and ways to access liquid cash. However, we want to make sure that they think through any withdrawals carefully, so we offer them resources like lawyers and accountants.

Maintaining the Vision by Choice

Family members committed to the business do not want pressures for immediate dividends to trigger a sale of the business. They feel removing capital deprives future generations of the benefits of their legacy ownership. Instead, to deal with the pressures from those who want immediate returns, a generative family offers a path for individuals or a branch to sell their shares. By the fourth generation, not one of the generative families in this study contained all of the blood family members as shareholders. Instead, each family offered a choice for family members to opt out of the family enterprise. (Some family trusts, however, do not allow this option.) Generative families become, as my colleague James Hughes, Jr., observes, families of affinity.3 When an exit path is offered, each family member must voluntarily decide to remain in the collective. In this way, they remain a family by choice, not blood.

This shift is especially important because family enterprises tend to limit the profit distribution to owners, preferring to reinvest in the company for the benefit of future family owners. Those who want immediate liquidity are encouraged to sell as in this example:

In our family, this reconsolidation allows family members who are not interested in the business to cash out. These members don't understand the business; they just want the highest dividends. Now they can sell their nonvoting shares and do what they want with the money, leaving the few who are truly committed to the business to reinvest in it. This worked well for the second and third generation. In fact, this method has been a sustainable competitive advantage for family businesses. Instead of dealing with disputes over high dividends versus reinvestment, they're able to take all that energy and focus on customers and associates.

A fifth-generation Asian family had this process for reducing the number of shareholders:

If we continue letting the family tree just grow without any thought of pruning, the dilution will become too great, and we may not be able to maintain the original vision of the business. It started with my uncle, then my father had four sons, and although my father gave me a bit more of his shares, the dilution really continued. If I continue to share with my children, then each branch of the tree will become very small as we move on.

I shared my idea about tree pruning with another second-generation family business leader. I suggested to the second-generation business leader that we needed to find a way for those who want to exit the family enterprise to sell their shares. We can't turn away family members, but we can trim the number of shareholders by allowing them to cash in their shares. Then only those who are more passionate about the business will remain as the shareholders. As we move to the fifth generation, we may have to do another pruning.

Some business families face another kind of liquidity event: the dissolution of a trust.4 Most trusts have an ending date, but when they are set up, the ending date may be generations away, so there is little consideration of what the date means. However, when that date actually approaches, the beneficiaries of the trust need to make a choice about how the trust's assets will be held in the future. They must decide whether they want to remain together and, if they do, how to invest the money. Here's how one family dealt with this issue:

Each branch had significant assets and trusts. Eventually those trusts would break, so the question was: How do we keep people engaged together? What happens when people have the freedom to leave? In 1995, the sixth generation gathered for the first time. Three of us fifth-generation leaders asked them to help develop a strategic plan for the trust company. We began to anticipate what would happen next.

“Diversifying” from Single Business to Portfolio

The evolution from owner/managers of a legacy business to managing a portfolio of businesses often arises when a new generation of young leaders begins to take over. This generation arrives with new energy, top-notch business educations, apprenticeships, and commitment to the family. These new leaders may see challenges ahead for the legacy business and investigate possible ways to renew it, reinvest, expand, or take on other investors. For example, liquidity from ESOPS (employee stock ownership programs) might allow some family members to cash out while the family continues to own and control the business. Conversely, offering stock to key family executives or advisors might enable them to continue to contribute to the company. Family owners may then seek opportunities to buy another business or pursue new investments within a family office or private trust company. These families discover many opportunities. They may be large enough to create an internal economy in which different family members can invest in certain projects, each with different degrees of cross-family ownership.

After harvesting, the family comes to own not one but several assets. Harvesting profits or selling a business may allow them to begin an investment fund or even buy new businesses. They often accumulate real estate, lovely family homes, land they lease to their business, and other investment buildings. They may form a family philanthropic foundation, which can involve family members. With several ventures and accumulating capital, the family needs to define its goals and policies and allocate resources to each asset. Even if they have managers for each individual entity, the oversight of the whole portfolio of ventures, balancing priorities, allocation and harvesting of funds, and new directions, some group of family owners must make decisions across assets. These decisions must take into account what family members in current and future generations want from the family wealth. Some will look for new ventures and others will pursue a social or philanthropic path.

After selling the legacy business, a business family has a rare opportunity to regroup and redefine itself. This opens the door to new entrepreneurial ventures by the family. Here's how one family created a new enterprise:

Today we don't have a fancy public family business. We have a tightly run, profitable business that provides investment opportunities available nowhere else. Our real estate department operates at a 99 percent occupancy rate. We have malls, apartment buildings, and offices. The trust management looks after the partners of a private capital fund with nine different managers across a variety of disciplines, including venture capital. All this provides opportunities for each generation. Although we don't have a visible business any more, we don't want to lose these opportunities for future generations. We hope for new entrepreneurialism and new invention.

While the older generation and professional managers may tend toward a conservative approach and risk avoidance, the emergence of a rising generation with a desire for innovation can move the family in a more entrepreneurial direction. The entrepreneurial energy of the new generation can challenge and balance the conservatism of the older generation and the professional business leaders. The family needs to engage these talented young people after they have developed capability and credibility but before they are fully established outside the family orbit. The family also has to initiate checks and balances on investments and new ideas so the enthusiasm and desire for risk by the younger generation is balanced by prudence. However, the older generation cannot be too conservative. One family missed the opportunity to invest early on in one of the Internet pioneers. The younger generation presented the idea passionately and thoughtfully, but the family was not willing to take the risk.

A European manufacturing business went through this evolution. As described below, two generations had to work through their differences:

The company rose from our single operating family business into a financial holding company with a family office. We needed to diversify and shift our focus beyond our industry in Europe. There were a number of issues that were hotly debated between the third and fourth generations. Should we sell the business? If we sold, how should we invest the proceeds? Should we invest in more diverse holdings, or should we distribute the proceeds to the shareholders?

Financing had become more difficult. If we went to the bank, we were offered higher rates, so we decided to separate the export activities in Africa from the core company and set up a holding company at the top. Some noninvolved family members were allowed to separate themselves from the core activities. This was a positive thing because it allowed the managers to make decisions without needing to get input from these members.

This Middle Eastern conglomerate typifies the organization of non-US family ventures that have diversified into many parts:

The family holding company used to be comprised exclusively of family shareholders: these shareholders held either 100 percent or a majority stake in all of our businesses. But last year, for the first time, we took a minority stake in one of our own SBUs because it required such a heavy investment (it was a supermarket chain). Outside investors put in money; now we're 49 percent, and they're 51 percent.

A family enterprise can contain both public and private business entities. They may be combined into a family holding company, as was done by this fifth-generation European conglomerate:

On the private side, we have a holding company, which is the original company. This now amounts to about 50 percent of the public company. The public company has four economic drivers: a power utility, a commercial bank, a consumer goods company, and real estate. All of these are public, but the private holding company holds a big chunk of the public company. We now have a market cap of about seven billion dollars.

A family with a legacy business dating back more than a century started a family partnership outside its public company. This partnership had a family advisory board and two family member executives who joined the business after working for venture capital and financial firms. Their venture capital investments fit the interests of their rising generation and were supported by the capability of experienced family and nonfamily leaders.

The transition to a portfolio of shared assets represents a deep transformation of the family, as this European company learned when it crossed generations:

In 2009, we had a liquidity event: we sold part of the farming company. This enabled us to buy out my grandfather, so he could retire in peace. We also had funds to buy out the generation of my father and my uncle. However, this raised a lot of disagreements. Some people wanted to sell the company while others were absolutely against it. It was a very difficult time involving many arduous and heated discussions.

Eventually, the majority of the family agreed to sell the company. This was a momentous decision because it was our core business. Next, we reached an agreement with the older generation about a generational transition. Ultimately, we were able to buy out the elders, and we ended 2009 with my generation in control of the family council.

Moving to a portfolio of businesses and other shared assets also allows for differences in the type of family leadership. Instead of a single leader, the family might select multiple leaders with different skills who manage different types of assets. Some families, especially those outside the United States, allow family members to acquire and manage different businesses. However, the portfolio needs a central holding company or board of directors that can manage the interaction of all of the assets together. The legacy company may have had a single family leader in the previous generation; the shift to a portfolio opens the door for shared leadership by family members who can oversee different areas. A designated next-generation leader can never have the authority of the original business founder, as he or she answers to many other family owners. Accompanying a designated leader, there is usually a board, investment committee, or special task force to diversify the family investments.

“Grounding”: Family Offices as Centers for Governance and Family Identity

All over the world, we see a dramatic growth in the number of entities called family offices. After the success of a family business, the family might begin to accumulate wealth from other assets. A “liquidity” event like a business sale or accumulation of capital from profits creates the need for the family to manage assets and investments outside the business. At first, if the business is privately held, the other assets can be managed from within the business. But if there are other shareholders or the business is sold or goes public, the financial affairs of the extended family will need to be managed separately.

A family office provides new services to a family, including tax filing and legal compliance, financial advising, wealth portfolio management, support for family lifestyles, administration of trusts, and estate planning. The office also supports family meetings, governance activities, and family education. It lies between the extended family, its business, and its financial and business entities. Having new focus and new “center” means that the family often has to alter its identity and how it sees itself and operates.

The location of these services outside the legacy business creates what is called a family office. If the family has a large amount of capital or multiple assets, the office can be quite large and contain a large professional staff. In effect, it becomes another business owned by the family that must be governed. Forming a family office after the sale of a legacy business creates a new center for the identity and shared engagement of the family apart from its business. A family has to decide whether it wants its own office or whether it wants to join with other families and receive these services through a multifamily office, trust company, or financial firm.

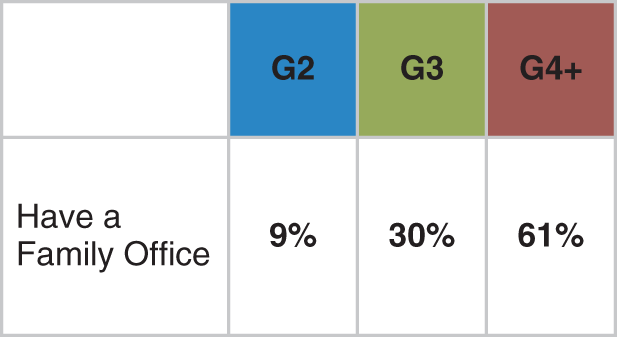

Nearly two-thirds—63 percent—of the generative families in this study have a family office. (See Figure 5.5.) With each new generation, the likelihood of having a family office increases. (See Figure 5.6.)

In the third generation, only a third of our families had a family office. By the fourth generation, 61 percent of our families had one. Forming a family office is often not a clear decision at a single point in time but may evolve as the family requires attention to taxes, investments, personal expenses, philanthropy, and shared family activities outside the business. While this makes the governance more complex, a family office enables the family to remain together as an organized, value-creating entity.

Figure 5.5 Percentage of generative families with family offices.

Figure 5.6 Increasing percentages of family offices over generations.

A family office may be created after the sale of a large business as described here:

We have an investment management committee that recommends certain investments—and we do a bit of our own research. We also have a family office with a very small staff. We have experts in investments, legal matters, philanthropy, and tax preparation. For some things, like tax prep, we might pay a little bit more, but we feel that we're getting the latest and greatest strategies.

It is not unusual for a G4+ family to sell its legacy business and diversify. The maturing business may not offer the returns that could be realized in other ventures. As the family grows, some family members of the geometrically expanding family want to exit the family enterprise. The family must design and implement clear policies to govern the trading of their shares. Upon such a sale, many families create or expand family offices to manage the proceeds for family members who choose to reinvest and to take advantage of opportunities not available to individual investors.

The families studied here see themselves as much more than family investment groups. They see the family office as multidimensional: it helps them manage not just their money but also the family's many familial, social, and philanthropic connections. It is the center for family governance and educational activities. In these cases, as the following two examples reveal, the sale of the business is not an end but a new beginning.

One G4 family divided into branches eighteen years ago after an IPO led to the sale of its business and creation of several family offices. One branch with forty family members came together to redefine how the members wanted to work together. They felt deeply connected to the tradition and values of the family, but now, as members of a financial family, they developed governance appropriate to their financial future.

Every two years, they hold a family assembly, combining fun, strategic review, and shared learning. They already had a family council, and they developed a family constitution. It included provisions for a shareholders meeting twice a year and a foundation that met several times a year. They have begun to convene a next-generation group and are developing clear guidelines about access to money and distributions. When an issue arises, they deal with it within the appropriate group.

Another family office began a generation ago with the sale of the family's remaining interest in a large public company their ancestors founded at the turn of the twentieth century. The sale enabled members of the three large family branches to decide whether they wanted to be part of the new family office. A majority signed on, and they have continued to create financial wealth. The board contains members from each of the three branches and from three generations. Members of G4 have moved onto the board and management of the family office. One hundred family members travel to the annual shareholders meetings, though the family would like to have even wider participation from its seven hundred family members.

The family has not been without conflicts and tensions. In order to resolve them, they have committed deeply to values of transparency, trust, and engagement. They exercise this commitment through the election of thirteen family members to the family council, which holds open meetings:

You foster trust through being open and through communication. If you don't have these things, communication and openness, you can't really have trust in any kind of relationships, professional or personal. If people don't feel that, they don't add to the connectedness of the family…. So the role of the family council is trying to straighten out some of the ill feelings over the years. People have left the business because they didn't feel trust.

This family has a deep tradition of values about family connection, not only in regard to governance but also as a way to enhance the well-being and development of each family member. The family has used its resources to support, for example, a family member who is an accomplished artist and to encourage other family members to “follow their dreams.” The family has frequent family gatherings. There is a family website that contains a growing library of family stories and interviews with elders who are videotaped at family gatherings. The family has developed a seminar series for younger family members on topics like tax, budget, investing, and insurance; these seminars are attended by thirty to fifty young family members. Since 1980, there has been an auxiliary—or “junior”—board for family members who want to learn about finances and become involved in governance. This group has graduated family members to join the official board, which includes nine family and four nonfamily members.

As with other types of family business, the family exercises control over its assets. The family has values about investments, and the family members want to sustain their identity as a family. Moving away from a single legacy business, the family office becomes the heart and soul of the family, the place where the family efforts are centered. If there is a family council, a board, family activity for education, a family vacation home, or support for individual households, the family office is where all these things are coordinated. Providing these family-related services is seen as worth the extra cost.

The family office oversees and administers assets beyond the legacy business. Acquiring additional assets allows the family to diversify; this lessens the risk of owning just a single huge asset. The diversified family office might include a trust, a holding company, an LLP, a private trust company, or other forms of partnership. It is governed by a board or trustees separate from the board of the legacy company. Family members can be board members, owners, staff, or CEO of these entities. They make the “business” pillar of family governance a sort of double pillar as the family office grows alongside the legacy business. Family conglomerates have complex structures that may own several large investments and companies. The goals of the family office are to preserve and grow assets, build a diverse array of businesses, and act as a center for other family activities.

Why do generative families often prefer single-family offices rather than being part of a shared multifamily office (a less expensive alternative)? This is because in addition to the financial services, the family office acts as a clubhouse and community center for the extended family. If the family is not widely dispersed, the family office has even more value to the family. In visiting family offices, one often finds a museum of family artifacts and long-serving staff who are close to family members and are available to assist them with issues and concerns. Members can get help not only with tax and financial issues but also with relationship and personal issues that arise in the family. Family office staff can help negotiate prenuptial agreements and divorces, assist in buying houses, boats, planes, and art, and attend to safety and security. There are places for family meetings to be held and places to store and keep family records. The office embodies the family's identity and commitments.

To allow the family to act as its own trustee for a family trust, a complex, highly regulated bank-like entity called a private trust company can be created. For example, a family that owned and controlled a large public company began to diversify by selling stock in the business. The family needed a home for these new investments, and it wanted to consolidate the investments that were held in various institutions and trusts. The family could justify the expense of setting up a private trust company because it wanted to be actively involved in investment decisions using the wisdom of its talented fourth generation.

As a family accumulates wealth, it often wants to invest as a family according to its legacy values. The family sees opportunities to combine its values with its investments. However, some family members may not share these values or want to invest in other ways. The solution to this conflict lies in allowing family members to cash out. Many families report that when they set up their family office, they offer family branches and members the option to exit and take their money out and also an opportunity to initiate a new period of growth or redefine their business and investment values.

Larger families have more complex and varied needs for their family offices. They may have farming, ranch, and vacation properties that need active oversight and other natural resources with complex regulations and tax implications. In addition, they may have venture capital arms with active or passive investments, concerns about impact and social responsibility, philanthropic arms that oversee foundation assets and the foundation itself, and other personal investments by family members. The family office might manage investments and personal affairs of many individual households. For example, when it sold its legacy business, a four-branch family split the proceeds. The largest branch formed a family office and moved into new investment areas, but this new family office served only sixteen of the sixty-four family members.

Some family offices might oversee the initiation of ad hoc family task groups. One such task group might be an investment committee to manage the family investments. Other families might have small internal offices and outsource the investment management to other financial advisors. The emerging functions of the family office allow the expression of innovation and entrepreneurial impulses as the enterprise moves in new directions.

The Structure of Resilience

Generative families are characterized by how they handle planned and unplanned transitions—the degree to which they anticipate and respond to emerging challenges. Behind the family's success there is often a struggle inside the family, first about whether to change and then about how to accomplish that change. After each transition, the family develops increasingly complex business and governance structures to manage its growing enterprise and family. The existence of these structures enables the family to discover their new path and resolve their differences.

Family enterprises, even generative ones, make mistakes. One new family leader initiated the purchase of a competitor, telling the family he would make it work. It didn't. As a result, the family learned to be more involved in such decisions. Another enterprise was not performing well when the new generation took over. The members of the new generation didn't want to sell, so instead they cut costs and reduced family perks in order to turn the business around. After this wrenching change, they had to rebuild family relationships. The overreaction was forgivable; in fact their continued success stems from their willingness to forgive and move on.

Unanticipated changes, like the early death of a key family leader or the emergence of new technologies, can tear a business apart. Generative families, however, act decisively in response to each challenge. At best, the family anticipates a crisis or at least sees an early warning sign.

We see a three-phase resilience cycle in how generative families respond to change:

- Prepare/anticipate: Even when they are not preparing for a specific change, the family expects and anticipates broad general changes such as the need to develop a new generation of family members or prepare for a shift in customers or products. They notice early warning signs and face their import.

- Engage/decide: As a change approaches, generative families gather to consider what it means. They engage multiple family members and listen to differing points of view before they take action.

- Redefine/renew: After the change, generative families do not go back to the way things were. They find a new path and work to implement it. While they respect tradition, they are able to let go of anything that is obsolete.

Another way of viewing resiliency is as a learning mindset. Rather than trying to dominate and impose their will, family leaders are open to new ideas from inside and outside the family. Businesses that exhibit resilience in the face of continual change have been characterized as learning organizations. The ability to question old ways and experiment with new ones is an aspect of resiliency, especially important to counteract the conservative tendency of the family owners. Without learning, there cannot be real change.

Dealing with Pitfalls

In spite of a family's best efforts, however, many pitfalls can derail the enterprise. It can overexpand or become too focused on family politics while neglecting the external challenges. A business family might think too highly of itself and overvalue its business. A family may idealize its values to the extent that it ignores signs that the family is not living up to the values. In order to bring such tendencies to the surface, one family decided, “We should have an advisor as an ombudsman for family members who don't feel comfortable coming directly to another family member with a complaint or suggestion. We depend on her for content at the family meetings.”

By facing challenges or issues that may be buried or ignored, the family becomes aware of the impending need for change. The initiative for a major transformation often arises when a new generation comes into power. When a rising generation takes control, it's important that its members take stock of what they have inherited and consider what is needed to sustain that inheritance. As one family member put it, “The third generation received the reins of the business about ten to twelve years ago, though, at that time, they were no longer young. One of their bravest decisions was to remove themselves from operations. Everyone that worked in the business left their executive positions, and they created new regulations among themselves to allow new leadership to emerge.”

Because generative families pay attention to warning signs, they quickly become aware of upcoming difficulties and latent signs of discord. According to one family member, “It's easy when the company is doing well, but it all changes in a difficult business climate. You need to build shareholder relationships to prepare for tougher business times—for unforeseen economic or global transitions.” Another younger family member noted, “We looked at our whole organization all the way down and made changes to fit our generation. We realized that our dynamic and needs were completely different from the older generation. The structures we had in place were obsolete. We worked for a year reevaluating our whole structure.”

Generative families are clear that the purpose of family enterprise is for sustaining enduring values as much as profit. Generative families view values and success as connected; articulation of clear values supports long-term business continuity. Poor business results can be a sign that the culture has not been attended to—or sometimes, good business results can divert attention from a company's culture and values. In the excerpt below, a third-generation leader tells of losing his way and the measures taken by the leaders to regain the company's values:

Another transition led us toward value-based leadership. From the early nineties to the 2000s, the company tripled in sales and increased approximately by a factor of nine. However, we lost our way relative to values, and I lost my way as the leader. I was terribly focused on acquisitions and new products growth, but I lost the how, the cultural part. We began focusing on the executive chain, working eight days a year on leadership development and value clarity. When we rolled this out to the company, employees started taking this stuff on and asking for more. We began to embody values-based leadership; in fact, these systems and processes are in place today. That was a single pivot point around culture in the history of the company.

Family conflicts about business issues can be difficult for a family to resolve, but generative families are characterized by making tough decisions and carrying them out. Here's how one family handled conflict:

It's hard to work with your family members. Specifically, my father and one of his brothers have had a lot of differences; they hardly ever agree. One is extremely conservative, and the other is more progressive, and this has caused a lot of issues over the years. For example, they argue a lot during the board of directors meeting. When the consultant came in, he said, “My goodness, this needs to be settled. You have to resolve your differences.” He had some strong conversations with them and tried to teach them conflict resolution skills. It helped, but they still have their ups and downs.

Members of the first and second generation of a generative family build a foundation of culture and values that leads them to be adaptive and resilient. We present the common elements of this culture in the next chapter. As families and as businesses, they are open and transparent and able to learn and grow in their interactions. They fight the tendency to avoid or deny the need to change. They listen to the new voices of each generation, seek new ways of doing business, and learn from external resources and teachers. They develop capabilities that are reflected in their family business culture and in their governance mechanisms.

Taking Action in Your Own Family Enterprise

This chapter presented a view of the family enterprise as an evolving social system that must develop the capability to be open to continual change. As you look at your family across generations, here are some activities that you can do to reflect upon your own resiliency and changeability.

Facing Transitions

Every multigenerational family enterprise has experienced major transformations like the Big Four (harvesting, pruning, diversifying, and grounding). In addition, each family can look ahead and anticipate the need for any of these transformations in the future. Success in your family journey depends upon how well prepared you are when the event occurs and how well you realign and redefine your family in response to it.

As you think about each of your family's major transformations, reflect on when it took place within your family. For each one, consider how you approached each of the three stages of preparing for change. You can start by answering these questions:

- Has your family gone through any of these major shifts?

- Do you anticipate the need for any of them in the coming years?

You might then conduct an assessment of how you managed the transformations that your family has experienced. This assessment can be done from the perspective of preserving family connection and business adaptability as well as what you might have done to improve your handling of the changes.

| HARVESTING | PRUNING | DIVERSIFYING | GROUNDING | |

|

Prepare Anticipate |

||||

|

Engage Decide |

||||

|

Define Renew |

It's never too late to set in motion positive measures to make your family change-ready in the future. Toward that end, you might want to look ahead at possible major changes and consider how your family is anticipating and preparing for them.

Family Enterprise Timeline

As you learn about and explore the history of your family enterprise, you can see it as a journey that you can record on a timeline. This will be used to develop your family enterprise history. At the bottom of the paper, you should make a dateline showing the years. You can begin on the left with the date of the founding of the legacy enterprise (or another meaningful date, such as the birthdate of the founder). Divide up the length of the paper with the years.

Next, fill in the date of the founding of the legacy business on the left, and about four-fifths of the way to the right side, make a line designated Now. Beyond this line, you can speculate and anticipate events that may happen in the future.

Now, begin to fill in the key events for the business and the family. You might divide the paper vertically into a top and bottom half. The top might portray business events and the bottom events related to the family. Some families construct a timeline together by placing a large sheet of butcher paper, several feet long, on the wall. You can then fill in dates and events using marker pens. Other methods include large sticky notes that can be moved around and family pictures related to major events. Whatever method you choose, in the end you will have a timeline of the key positive and negative events in your family and business history.

If you are building this timeline with other family members, start with the memories of the elders and then the recollections of the younger generations. Also, ask different people to recall the same event, because people are likely to remember important events differently.

Resiliency

You, your family, and its various business enterprises have experienced many changes and turning points. Now, with the help of the timeline you constructed, consider how well you anticipated or responded to unexpected events as well as those that were caused by your own actions. You can focus on each important positive and negative event, its consequences, and its impact.

As you reflect on each event, discuss what you did to prepare for or anticipate it. Then consider what was done afterward to build on the new situation and take the family and family enterprise forward. You can talk about each of the three phases of change that were described: Preparing/Anticipating, Engaging/Deciding, and Redefining/Renewing. How did your family experience each stage? After you have looked at what was actually done, you might discuss how you could have approached and recovered from that event more effectively.

Future Casting

- Look ahead to the future and the changes you can prepare for and anticipate.

- Select a time in the short or medium future that makes sense to you such as the next five years—or a longer period like ten or twenty years. Alternatively, you might select an important date, such as the time a trust ends or when a family member plans to retire.

- Mark that event and imagine together what it will look like if you prepare for and respond to that change in a resilient, positive, successful manner. Generate a picture of what success will look like.

- Next, consider the most effective things that you as a family can do to prepare for and anticipate that event.

- Finally, consider what specific steps you and your family can take right now to begin to prepare for that event.

Notes

- 1. The harvest concept comes from James Hughes, Jr., personal communication.

- 2. This is more common outside the Western world.

- 3. My work is much influenced by Hughes's work. His most recent offering, Complete Family Wealth, was cowritten with Susan Massenzio and Keith Whitaker (Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons, 2018). It presents many useful concepts, including that of the family of affinity.

- 4. The film The Descendents wonderfully captures the ferment in the family when a trust is due to dissolve and also the powerful role of the family trustee.