CHAPTER 10

Governance: Organizing the Interconnection of Family and Business

By G3, a generative family has become a very wealthy, loosely connected tribe of families with a common interest. They manage huge resources; hence they are more than a social group. Because of their shared legacy, they need to organize a tribal government, to manage assets, resolve disagreements, manage family and business affairs, and create a common vision and purpose. Each family member must become a citizen of the tribe and take responsibility to participate. This government consists of a tribal council that oversees and organizes personal relations, and other councils that oversee their business and financial resources.

As a tribe of dispersed families, the family needs to sustain harmony, community and continuity. They need a well-developed family organization that runs parallel to its business interests. Family governance is one of the major achievements of a generative family. It enables the family to steward and use its wealth to fulfill its values and purpose, and maintain appropriate communication and influence over its business governance.

Governance takes the generative family beyond business and legal requirements for financial oversight. The family initiates special activities outside the business but taps into the resources and opportunities offered by its business and wealth. Many incredible activities become possible to this type of family. A family can remember and preserve the family history and legacy, educate and enrich the lives of the children, have great family vacations, serve the community, establish philanthropic ventures, and advance the values and principles the family wants embodied in its businesses. In this chapter, the central questions are: Who makes all of this happen? How do these things happen? The family, not the business, develops a “tribal council” to manage these activities. Family governance signals a separation of activities of the family from those of the business.

Developing governance is a challenge and family drama that takes place over the course of generations. If individual family members have different interests but want to work in concert, they need clear agreements, councils, and working committees to implement them, and they have to be accountable to each other. This chapter, and the two that follow, present how and why generative families develop family governance.

The Purpose of Family Governance

Family members are stewards of wealth in trust not just for their own use but for future generations as well. The future is safeguarded by people who benefit in the present. The family is growing in number and usually contains several ventures with different degrees of complexity. They must develop a system of organization, policies, and decision-making entities that together form the governance system. To manage and safeguard the family's growing wealth, governance allows family members to add purpose, organization, and focused activity to their lives.

Governance is an element of all family business: a board is needed to manage business entities for the owners. But for a generative family, governance takes on added importance and complexity: the owners share values and intentions and want to influence their assets and ventures and develop their connection as an extended family. Governance must be implemented in the family as well as the business. With the passing of the lone autocratic family leader who is able to impose his will, conflict is inevitable. Generative families must resolve differences in an acceptable way by developing processes for working together and making decisions. However, it takes commitment, creativity, hard work, and practice to make governance work.

Families new to wealth may find governance a confusing concept. It was not on the radar of the wealth creators or even their children. Family governance is a unique and highly demanding endeavor not needed by most nonfinancially linked families. If it does not own valuable assets together, a family has little cause to develop formal policies, activities, agreements, and working groups. However, a family with newly acquired wealth discovers much that must be done as a family to become effective stewards at managing all types of family “capital” beyond the third generation. Family members cannot just be a family; they have to organize and commit time to take care of their assets, build a shared identity and community, and hold each other accountable.

Generative families develop structures and processes to manage the natural tension between each person's self-interest and collective interests. When the family reaches a certain size and wants to continue to act in unison, the process must be managed consciously and clearly. The personal values, expectations, interests, concerns, and feelings of each family member are the foundation upon which governance is based. As a family tribe, the family takes on projects and tasks separate from the business.

Why does a third-generation family need to govern the family at all? Generative families often refer to the adage, “With great wealth comes great responsibilities.” Even if they aren't active family leaders, family members should learn to be good citizens, engaged, responsible participants in family activities. They can't ignore their wealth, nor can they just sit back and enjoy the harvest. While family members have different degrees of ownership and levels of influence over decisions, every family member should have a voice in what happens. Because they care about one another, family members want to listen to other members. Each family member has a responsibility to be informed and thoughtful in offering his or her ideas. Unlike public companies, in a family enterprise the next generation of owners is already in the room. The process of family governance allows the family to anticipate and debate everyone's ideas.

Many family inheritors are not very well informed about their business or financial situation. The legacy family business may have been sold, and the family may now share a variety of investments. Perhaps the family opens a family office to look after its assets (as was true about half of the families in this study). If the whole family shares ownership of business, investments, land, or a foundation, whose values or vision guides the family? While each business and or asset may each have its own governing board, the family members as owners or owners-to-be want a voice in what direction the family goes and what it does with the wealth that flows to the owners and beneficiaries.

Family governance is a blend of need, opportunity, and possibility. The work of the family is not about increasing wealth but about what the family does with its resources and how working together leads the family to achieve more than any family member can achieve on his or her own. This added value is often in nonfinancial areas: human, relationship, and social “capital.” As the previous chapter showed, the generative family creates an extended family community that expands upon the family legacy, builds trusting and enduring relationships, educates young people, and offers them roles in philanthropy, management, and family ventures. Family governance is how that is achieved.

Governance is the process by which the family makes these choices and develops the structure to put its decisions into action. It is not democracy; regulations and policies define the precise rights and responsibilities of different types of stakeholders. They may limit the available choices radically. A few people may have all the votes, but because they are part of a family, they want to inform and listen to one another. The essence of governance is balancing the perspectives of each group. The generative alliance contains elders who are majority owners and leaders, advisors that bring skills and loyalty, and excited rising generations who offer new ideas and energy. All these voices need to be heard, aligned, and integrated. This presents a huge challenge for a growing, extended family with a portfolio of ventures and assets. Governance is not an option; it is a necessity.

Business ownership is not evenly distributed. Some family branches inherit larger shares of ownership, and family members may sell all or some of their shares. Other family members—including young people, trust beneficiaries, and married-ins—are not owners. One major reason for creating family governance is that family members must learn that while being part of a family of wealth has its perks, every family member has a different claim on the family wealth and role in influencing it.

This first-generation matriarch looks toward her grandchildren and observes that family is more important than the family's huge business. Her legacy work has shifted to the family:

I thought, “I will make a strong family organization while the business organization will be quite loose.” Grandchildren can decide on their own what they want to do. The family is to me the most important element. In business, everything starts with the family. You must take the time to develop each member to their potential. That takes time and education. People don't understand how important that is, and they underestimate the time, care, and devotion it takes to build a strong family. But for me that's where everything happens, so that's where we spent most of our time. I guess if you look at our family business, it would be a combination of individuation combined with collectivism.

What Ignites Shared Family Governance?

Rudimentary governance is always present in the family; as it gets more complex, it must become more explicit, collaborative, and inclusive. G1 already has its own form of governance, but it is autocratic; one or two wealth creators make all the decisions, with no oversight or review. When the family contains a single household, governance can remain informal with few explicit policies and roles. The second generation expands to include more people and greater complexity, as this family member notes: “We often say the founding generation's philosophy is ‘follow me up the hill, my way or the highway.’ To survive, G2 needs to learn more about working in an interrelated sort of way.” The G2 siblings have grown up together, but they need to learn to collaborate in making good decisions because they no longer have a venerable “father” to direct them.

To survive together, the third generation must go further. G3 may face a maturing business with increasing global competition and need for professional management, as well as pressure to raise capital or sell. This changing landscape often means finding ways to challenge family members who have become too comfortable doing things in a certain way. The family must establish a professional business but also an aware, competent, and engaged family of owner-stewards. The family does this by making the rules more explicit and detailed so that family members know what they can and can't do.

To finance its commitment to philanthropy, a G4 family realized it needed a profitable business. The family evolved from seeing the business as the place for the family to act on its values to seeing that the business was also the vehicle for greater projects:

Our Christian heritage was the reason the company existed, so that the family can contribute to charity. While sales were growing, profits remained flat. We asked: “How come we don't have as much money to give away? What's going on?” We told the older generation to look at whether we keep the business, sell, or restructure it. We had all family branches involved in that discussion. One thing that's important about the vote is that it had to be unanimous; everybody had to agree on the next step. We looked at everything from selling the business to going public to the status quo. We want to do the right thing, and that is sustain this business for future generations.

The need to adopt explicit rules and clear policies for decision-making seems reasonable, yet in a growing family, some family members may not initially grasp its importance. That is why there must be education. If they are not informed, newer family members do not understand why things are being done in a certain way. They may become disengaged or even hostile to change:

It's been a challenge trying to get everybody to understand the need for a more formal governance process. My younger brother and my mum are not as connected to the business. My mum has been on the board for a long time and wanted to retire and separate herself out of the whole process and just be a grandmother and do her thing. So it's been a challenge trying to get us together and say, “How are we going to engage the in-laws before we get to that fourth generation?” and making sure we have a plan for the next ten years.

Many families hire advisors or consultants. While outside advice is important, family members must still be informed and engaged. They can get good advice, but they can't outsource responsibility for making it happen. The family should not become dependent on advisors, who can become an interest group of their own. As one family member observed, “It's a real challenge to choose what we do as a family and when do we look to outside helpers. The more somebody from the outside does it, the less the family must do it. It sets up a cycle. I'd like to see our family take more initiative to do these things that we're paying someone else to do. It makes me uncomfortable.” Other families are clear that they value working together to design and implement governance. By doing that, the family members buy in and feel emotionally connected to the work that needs to be done.

A major business transition can lead them to initiate family governance. While business leaders negotiate the business aspects of the deal, the sale of a family business changes the personal relationships of family members. The loss of the legacy family business can be traumatic to family members and the family as a whole. The sale can lead to family members losing their jobs as well as to a shift in leadership as the family decides what to do with its assets. This is a major governance project for the emerging younger generation:

In the eighties, we sold our original operating company. The fourth generation were all in our twenties or thirties, and our parents were getting older. We owned all these assets, but some issues and debates were going on in the management of the merger. We got involved, but there wasn't a clear family strategy. To deal with the transition, the older generation called for a series of “All Hands on Deck” meetings. They were held every two years. Very few third-generation members attended, so it was mostly the younger fourth generation from all over. We got to know each other. We debated the issues, looked at as basic an issue as who is considered a family member and who isn't all the way through to redefining our family values.

A transition to formal governance may also be triggered by the passing or retirement of an elder-generation leader who took care of everyone without training a successor or letting people know what he (most usually) was doing. If not before, then after this departure, the family is forced to rethink how things are done. As this fifth-generation heir says, “We're revisiting how our family office is managed and supervised. That was done for years by the patriarch, who had a certain way and didn't want to change. But we had conversations about the need to change into something more responsive to everyone.”

Building Blocks of Family Governance

A generative family begins with developing a boundary to separate interconnected family and business activities. Family governance is different from business governance, but they overlap. They can be seen as two “pillars” that work together. Each pillar has a purpose and must be organized around that purpose. Previous chapters have presented the business pillar as well as the organization of business governance. This chapter is about the family pillar. As the family becomes more extensive and has more people and more resources, it can do much more than just oversee business and financial assets. Emerging family members can be a creative force, supporting family members and the wider community. These activities are clearly separate from the business. (See Figure 10.2.)

The leaders in family activities are different than the family business leaders. Wise families discover that their business leaders have a great deal on their plate—they don't also need to be family leaders. Other people can step up to family leadership. Family and business leaders each organize different areas that together support and create the family.

|

“TRIBAL” FAMILY Family Assembly and Council |

PROFESSIONAL BUSINESS Board and Owners Council |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Figure 10.2 “Tribal” family versus professional business governance.

The second generation grows up together in the household of the wealth creators and finds it natural to take roles in the business. But the third generation may not directly know what the family business needs or offers—or may not even feel welcome. In their upbringing, many young people from business families are told, explicitly or implicitly, to be passive and not ask questions; they are told that they will be taken care of. G3 family members have always lived with the reality of the family's wealth and community visibility and respect. While they may know “Grandpa” as a kindly person, they do not experience the scope of his achievement in building the family enterprise. They know their family has significant wealth, but they may have different ideas of what the family should do or invest in. Do their ideas have any standing? They need clear direction about how they can legitimately participate.

Members of the younger “rising generation” inherit benefits of the family wealth, but they face many competing possibilities for their time and energy. They ask, “Why should we work together at all if there are so many great things we can do with our wealth and inheritance outside the family?”

To remain partners into the fourth and later generations, the generative family must attract each emerging generation family member to give of his or her talent, time, and energy. Generative families do not just expect new members of each generation to contribute and be part of the family; they use governance to invite these new members in with an attractive offer. Such families begin family assemblies and education programs to make membership more attractive and meaningful. Their goal is to recruit young family members to actively engage in family pursuits.

They also prescribe how a family member who does not want to be part of the family enterprise can leave and sell shares back to the family (see the section on pruning in Chapter 5). In every generation, some family members do not want to be pressured into family governance. Almost every one of the families in this study offers an exit mechanism whereby family members can leave the family enterprise and claim their share of the assets (with clear limits and guidelines for doing that). As James Hughes describes them, generative families are not any more a family of all blood relations but a family of affinity, actively choosing to be together. While they inherit wealth, family members in a family of affinity must actively “sign up” to be “citizens” of an active governance body of engaged family members, adding new ideas and new energy to develop and utilize what they have been given.

When all family members work in the business, they are in daily contact and can collaborate on policies and decisions. After family members disperse and increase in numbers, with many not directly engaged, governance allows them to create a bridge to the family enterprise and learn about their opportunity to contribute and become leaders. When trusts, trustees, and family advisors come between the family and the rising generation, family members must create their own personal entity to define their place. Family governance offers engagement opportunities to family members who are not employees or board members.

Governance is not completing a checklist of tasks; instead, all of its elements are interrelated. For example, a family council needs to be defined with goals, values, and policies; these form the foundation of a shared family agreement called a family constitution. The council is selected and represents the wider family, which must meet as a whole group. The process of holding a wider family meeting as a whole group has been called family assembly. So creating governance includes three almost universal building blocks—a family assembly, a council, and agreements in the form of a family protocol, charter, or constitution. The agreement and the council are like yin and yang: the council can't work without a protocol, and the protocol does not make sense if there is not a council and other active family gatherings (such as a family assembly) to make it a reality. The two chapters that follow look at each of these entities.

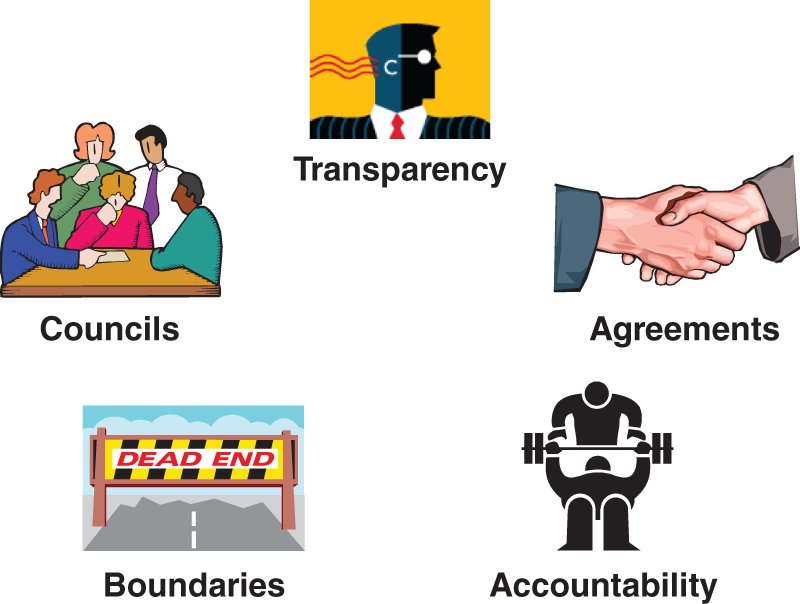

Many families feel that governance lies in the agreements and legal documents that outline how they hold and manage their assets. While this is a central aspect of governance, generative families view it in a larger context, consisting of an integrated, interconnected system of agreements, activities, policies, practices, and values. An agreement means very little if there is no meaningful path to put it into action. It is a social system, containing the elements seen in Figure 10.3.

All of these elements are interconnected. To start, a governance system must offer transparency and a free flow of information because people cannot exercise oversight or control when they can't see what's happening. Transparency is not always part of the original generation. The beginning of governance comes with the regular sharing of financial and business information that was formerly confidential. With transparency, there must be policies, practices, and rules specified in documents adhered to by all family members. The agreements are administered in family councils and boards that work in concert. These entities and agreements define boundaries and roles, which clarify and differentiate responsibilities and accountability and which define how representative leaders are responsible to the whole family. Unless all five of these elements are present, the generative family cannot operate effectively.

Figure 10.3 Elements of family governance.

A G2 or G3 family with a strong and thriving business (or several) realizes that potential family activities will not happen unless the family takes initiative. Such initiative can arise from anywhere in the extended family, not just the formal leadership. The family learns that assembly of the whole extended family is necessary for staying in touch, building relationships, and airing concerns, but it is not a good setting for making decisions or creating policies. For that, they need a smaller, more focused working group. This family council is convened by the family leadership as a sort of executive committee, listening to all of the family voices to help the family define what it wants to do together and setting up a family foundation, shared property, investments, or family office. Since the family has grown in numbers, the council is a small, dedicated group representing, and responsible to, the others.

The family council allows the family to conduct the “business of the family” having to do with business oversight, goals, and resources for developing family, human, and social capital. Family members may erroneously expect the business leaders to carry out these responsibilities, but they are usually busy with other commitments and do not have the time or the motivation to manage these responsibilities, so they fall through the cracks. The result may be family tension, conflict, or just lack of attention to things that are important, like assessing the capability and commitment of the rising generation to enter family leadership. The family creates a family council to have a nonbusiness mechanism to accomplish this. This will be explored in the following chapter.

Family governance separates family issues from those of the business, which are addressed in a parallel governance structure. There are many areas of overlap. As we will see, the family council, while not having formal authority over the business, may contain some owners and other influential family members. Their values, concerns, and voice are important messages for the board of directors. There are many ways that the family connects to the business, some formal and some informal, and governance organizes this input.

To operate effectively, the family council needs a working agreement defining its purpose, values, policies, and practices over what can be a huge, multigenerational set of family enterprises. The family has several preexisting agreements: trust documents, shareholder agreements, corporate by-laws, and policies, all of which guide the family enterprise. But family members don't often read these documents or fully understand what they can and cannot do or how various financial events will happen. These documents often raise more questions than answers.

Also, while these documents specify rules and practices, they often don't include the purpose and values that guide the family. And they have many holes. For example, documents may talk about rules regarding transfer of ownership, voting, or distributions, but different interpretations of these rules can lead to conflict within families. Drafting a detailed family constitution, charter, or protocol allows the family to formulate clear instructions for how these agreements work in practice. These questions include who makes decisions, about what, how they work, who is included, who implements decisions, how these individuals are paid, and how family leaders are selected.

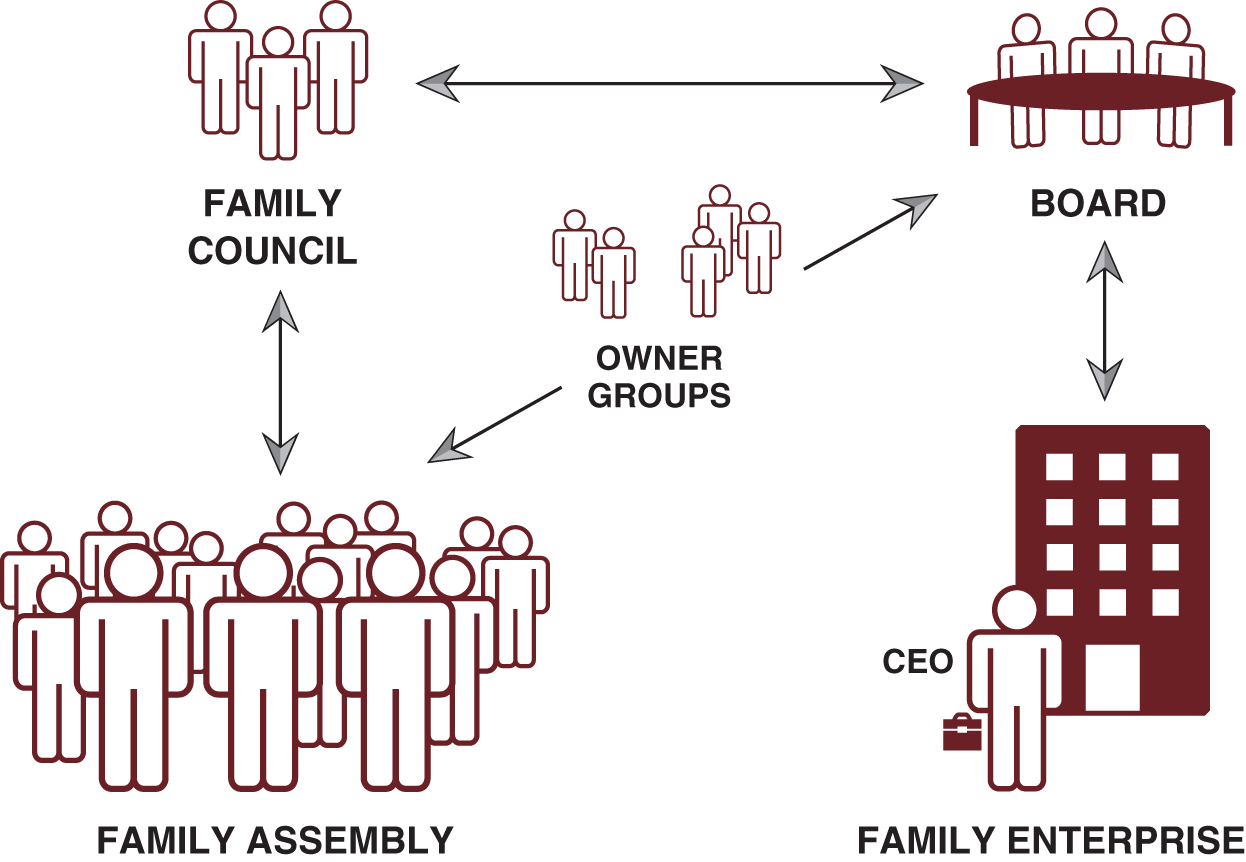

Linking Family and Business/Ownership Governance

The link between family and business should be open and fluid. Family members own the business and feel deeply and emotionally committed to what it does. They can move into the business by visiting, working there, or taking roles that relate to the various family ventures. Key purposes of the family council and owners' groups are to link family and business governance and educate and prepare family members to perform their proper roles. Figure 10.5 depicts the relationship of the two pillars of governance—the family and the business.

The family council is a parallel organization to the business's board of directors, which represents the owners. But family members are often owners, so the family faces the reality that while their governance structures are separate, the membership of these two groups overlaps. One of the key functions of the family council and family governance is to manage the relationship with the owners, who in turn create their board of directors and other oversight mechanisms. The family council and assembly are connected to the business and boards of directors via the owners' council and also via direct connection (and often cross-representation) between the family council and board.

Figure 10.5 Family governance structure.

Weaving Family and Business Governance

The board and family council each play a role in overseeing the family enterprise. The dividing line between the two is a moving target, set and maintained not by fiat but by negotiation. The family initiates a cycle of high-level advising and deciding but then defers to the board. The board listens to the family and makes the difficult choices and explains those choices to everyone. Here is an account of how a manufacturing business entering its fourth generation deals with this interplay:

We're trying to come up with criteria for family board members. I've been on a number of other boards, so I know something about how boards work. We're also developing criteria for replacing the four family board members. None of us are planning to go anywhere soon, but we need to decide the criteria so that the fifth generation will know where to look if they want to be involved. They can learn what it means to be a board member. When I entered the board, I had no idea what I was getting into.

At every board meeting we have a summary report from the chair of the family council. At the family council, we have reports about the board meeting. They're usually back-to-back: the board meeting happens one day, and then the family council meets the next day. In addition, we have a family relations subcommittee. This developed because our board chair wanted us to review our values. I began with a review and an updating of current family values.

The family council does several key things. They develop the values that the whole company lives by, elect board members, and build family relationships that encourage stewardship. So that's the family council. The family assembly is held every other year, and anybody can volunteer to help out with that. We encourage stewardship and involvement, so a lot of people want to participate.

When I got on the board, the selection and election task force was in major crisis. There was a lot of screaming by family members about this. We needed to develop our credibility with management as a family. We had gone through two CEOs in four years. I could see that the current CEO was not good for the company. This led to a big split in the family, though eventually everybody agreed with my assessment and he transitioned out. The next CEO did some good things but was also not in line with the values of the company or the family. That was a very difficult transition, as once again the family was split.

The most recent hiring of a new CEO finally led to a good one! But it also produced problems. These days, only a few family members work for the company. We have seven hundred employees and only three full-time family employees. Because one of them is my brother, I hear from him what's going on from the perspective of the employees. But he isn't in top management; he and my cousin are just below the top. Their presence can be a little tricky because my cousin and I on the board hear from family members who work in the company, but the other two family board members do not have that link. That's one of the complexities of being in a family business.

The nature of the link between family and business is often discussed in the start of a family council:

One thing our new council is considering is what roles should the council play in representing the family in the board of the company. Some of us believe that the family council should have members knowledgeable about our businesses so that when the family council expresses the family's desire or when there are issues regarding the functioning of the board, there will be council members who are knowledgeable so that their opinion carries weight.

Most family councils have clearly defined functions, but it is easy for the family to push the boundaries too far into business operations, as this account shows:

The family assembly meets every other year to develop the values that the whole company lives by, to elect board members, to build up family relationships and encourage stewardship. Anybody can volunteer to help, and a lot of people do. Because we encourage stewardship and involvement, a lot of people want to participate. But that has its limits as well. For example, we had a big to-do recently about salaries of family board members. The family council got involved trying to analyze the salaries of the board members. And that was not appropriate because they didn't have the experience. They just didn't have a clue, and so the board chair had to take that back and say, “These decisions actually get made at the board level,” and that was fine. We must maintain those clear role definitions.

This family realized that family members, especially young people growing up, often do not fully understand the responsibility of ownership. What is their role and responsibility if they become an owner or an employee? What if they expect to become an owner but are not yet one? One of the major tasks of a family governance system is to educate each family member in his or her role. The media is full of stories of how wealthy families interfere in their businesses, causing the business to lose value and even forcing a sale. Learning the appropriate role of a family member and having a clear plan for governance seems to have helped the generative families in this study avoid this fate.

This leads to one critical difference between family enterprises and public corporations. In addition to family owners, there are family members who expect to inherit ownership—owners-in-waiting. They know this will happen, and it is in the family's interest to have them understand the business and learn their future role as owners. There are also beneficiaries of trusts, whose business decisions are made by trustees; the trustees have a voice in the business future and the use of its assets. These potential owners and beneficiaries are important to the family and participate in governance. Family governance usually includes education and communication about the business, and these family nonowners also can share ideas and suggestions even though they are not formal decision-makers.

The council formalizes the connection between family owners, owners-to-be, and the business board often by having shared meetings. The family has things that it wants to know and suggest for the business, and the company wants to know where the family stands on key strategic issues:

Every board meeting has a report from the family council chair. She comes to the board meeting and does a summary report of what's going on. Then, at the family council, we have reports about the board meeting.

They're usually back to back. The board meeting happens, and then the next day the family council meeting happens. We've done it the other way, the family council meeting first and then the board meeting, and there are pros and cons to both ways. Not many companies have a family relations standing subcommittee. That developed because our board chair wanted us to review the values in the family. This led us to begin a review and updating of the family's values and how they want them expressed in the company.

Frequently there is another intervening governance entity composed of the family owners called, appropriately, an owners' council. This group has several functions that differentiate it from the board. It contains the owners, who may be too numerous to all be on the board. This group is especially important if the family has several ventures. The family might, for example, own a ranch and a publicly held community bank. Each has its own board. The family might also have a family office or a holding company containing a portfolio of businesses. The owners' council acts as an umbrella organization to define and integrate the goals and policies of each entity. It typically consists of family members who are actual owners (and maybe trustees of family trusts) and does not contain outside directors.

Boards, as we have seen, frequently have nonfamily independent directors who are not owners but whose expertise and wisdom helps guide the business. These directors want to know the goals and values that are held by the family owners, and they want to hear it in one unified voice. The owners' council is where the family aligns its goals, values, and priorities, airs conflicts, and then speaks to the board with a unified voice. It is needed in addition to the board when the family owners become more numerous and have concerns to share with the board.

An important function of a family council is communicating what the family wants from the business. Boards of family enterprises often hear different things from different family branches and individuals; they want a clear statement of the family expectations and intentions for the business. Here is how one family makes that clear to the board:

We have a shareholder agreement that lasts ten years. Then we look at updating or renewing it. Company bylaws guide the business of the company. One of the first documents the council developed was a family charter; we sought outside consulting guidance on this. It fundamentally talks about what we're committed to as a family, our core values, and the purpose for us gathering as a family within the family council as well as sets the direction for the family within the family council. One of the big distinctions is, as a council, we're really dealing with the “business of the family” not the “business of the business,” and so if we ever get on the line of “Is this really something we should be talking about or just the business of the business,” somebody will notice that and say, “Wait a minute. I think we're almost crossing the line here. We can always seek to get clarification if we need it.”

Within the last three to four years, we've developed an owners' plan, a document the family council generates through a committee. We present it to the board each year to give the direction for the board of the family's interests regarding the business. We've found that quite useful, and the board has acknowledged they also find it quite useful to know for the direction of the company. It talks about everything from what level of risk are we comfortable with and even when we talk about moderate risk, what does that mean to us exactly? The owners' plan hasn't changed much year to year, but we tweak it to try to get clearer about what that is for the board based on their feedback and questions that they have for us. I think we found that to be a valuable document on both sides.

The level of formality and organization of governance increases each generation to accommodate a larger family and more complex set of family enterprises:

The council is separate from the board. The council is about the governance of the family. They have nothing to do with the business governance. The board is the oversight piece for the business. They're like a business board even though they have family members on, but there's more independent members than family. It's completely different. The family directors on the board report to the family council at their meetings about the business, and the president of the family council reports to the business board about the family council, but the family council has nothing to do with running the business at all. Each of them has about ten family members that they call constituents, and each family council member reports to their constituents about what is going on in the business. They're elected by the family, not by branch.

The family above has four coordinators for education, governance, communications, and the annual meeting. The family council chair reflects, “I can categorically say, we would not have our business today if it had not been for the family council and the reunification of the family.”

As the family enterprise becomes highly professional, family members becoming stewards must in turn become more professional in their oversight. To serve in governance groups, they need a certain level of skill and need to do a certain amount of work. The family council creates that education for their younger members and defines qualifications for different roles, though sometimes the business also offers education activities, such as internships and seminars.

The family, through the council, has a voice (but not always a vote) in the direction of the company, but their ideas do not go directly to the business. The family's voice is transmitted through the owners' council or board. Some families allow individual family members to make input informally, but family governance usually specifies a formal process for the family to communicate its values and intentions to the board:

The owners through a lot of education have developed a written document that's given to the board every year. It's reviewed every year by the family council. If they have some things they want to change or if the board has a little pushback on something, they reconsider. This process tries to divide as clearly as possible the risk and return parameters that the shareholders wish to have in the company.

The following chapters will look in more detail at the family council and the family constitutions, family governance elements that work in parallel with the boards of family enterprises.

Taking Action in Your Own Family Enterprise

If your family has not considered governance, has tried to set up a board or council and not been successful, or initiated governance activity but feels it is not doing as much as it can, this book has offered a range of possible paths and practices you can draw upon. Governance is a platform to prepare your family to act as a creative force to develop the potential for wise, thoughtful, and productive use of its accumulated wealth.

Generative families outline a direction that you may not have considered for your family. While many of the families interviewed for this study developed governance in their third generation, it is never too early to do this. If you are in your second generation or living with success beyond anyone's expectations, family governance may not yet be part of your future plans. You may be working with advisors to invest or create an estate plan or trust. This book suggests that you can use this opportunity for a larger purpose: to consider the future of your family and your family enterprise, not as a task to complete but as a wonderful shared opportunity to see what your family can do as a shared cross-generational project. It is about possibility.

The first step toward engaging a family is to hold a family meeting for all family members, with a purpose other than just socializing. It can have a theme such as philanthropy or talking about the family's vision for the future. Families differ as to whom they want to include. Some start with just the blood family; others start with a value of inclusion and invite spouses. The goals of the meeting are to have a good discussion, not necessarily to make any decisions, and to create a safe and welcoming environment for each individual to have a voice and feel good about being part of the family. If the first meeting is successful, the family will decide to meet again and will begin to create a purposeful family community.

To begin to initiate governance, you need to get your family together, with older and younger generations considering what they want in the future. With all your family resources, they can imagine far more than the status quo. You can look at the future with two mindsets. First, you can think about what you need to do to anticipate future challenges as you have more people and cross generations. Second, you can consider what you might do, what you could do, that is creative, expansive, and worthy of what you have together.

What can you do as a family to move forward? We believe that you can invite the old and new generations of your family together to ask yourselves, “What is possible for us as a family together?” This is not a question with a single answer but rather an invitation for all family members to embark on a journey to consider what they can and want to do together and then to make it happen. Building a family council, holding regular family assemblies, and developing a family constitution are all interconnected and important in that they formalize and organize the good intentions of many family members.

Assessing Your Family Enterprise Best Practices

This offers your family a “snapshot” to discover how much you engage in practices identified as important to sustaining your family across generations and using your family wealth to make a difference in people's lives. It focuses on best practices in three areas—the family, the family enterprise, and the human capital of the next generation. These practices were developed in several research projects over the past decade.3

You can complete it yourself, with your own view of your family; or several family members can complete it and compare responses. Different family members—having different places in the family—view the family differently.

You may not agree on the presence of a practice in your family or on its need for the future. That can lead to a productive discussion, not argument. Your responses represent your perceptions of the degree to which your family has adopted, or needs to adopt, each practice. This sets the stage for a Family Conversation about how your family can grow, develop, and prepare for the succession and stewardship of the next generation.

If you are a family advisor, you can use this tool to assess areas of strength and those that need development in the future. If several members of your family complete this inventory independently, they can compare responses in a Family Conversation to explore areas of agreement, and where scores or perceptions do not agree. Then, as a family, you can proceed to develop a Strategic Family Roadmap, to design and implement the practices that enable your family to succeed across generations.

Best Practices for Multigenerational Family Enterprise

For each practice, indicate in the Current column, on a scale of 0–3 (0 = our family does not do that; 1 = we have talked about this; 2 = we are beginning to do this; 3 = we utilize this practice in our family), the degree you see your family using that practice at this time. In the Future column indicate how important you believe this practice will be for your family to develop that practice in the next three to five years (from 0 = very low to 3 = very high).

| Practice | Current | Future |

| Pathway I: Nurture the Family | ||

| 1.1 Clear, compelling family purpose and direction | ||

| 1.2 Opportunities for extended family to get to know each other | ||

| 1.3 Climate of family openness, trust, and communication | ||

| 1.4 Regular family meetings as a family council | ||

| 1.5 Sharing and respect for family history and legacy | ||

| 1.6 Shared family philanthropic and social engagement | ||

| Pathway II: Steward the Family Enterprises | ||

| 2.1 Strategic plan for family wealth and enterprise development | ||

| 2.2 Active, diverse, empowered board guiding each enterprise | ||

| 2.3 Transparency about financial information and business decisions | ||

| 2.4 Explicit and shared shareholder agreements about family assets | ||

| 2.5 Policies that support diversification and entrepreneurial ventures | ||

| 2.6 Exit and distribution policies for individual shareholder liquidity | ||

| Pathway III: Cultivate Human Capital for the Next Generation | ||

| 3.1 Employment policies about working in family enterprises | ||

| 3.2 Agreement on values about family money and wealth | ||

| 3.3 Support and encouragement to develop next-generation leadership | ||

| 3.4 Empower individuals to seek personal fulfillment and life purpose | ||

| 3.5 Opportunities to become involved in family governance activities | ||

| 3.6 Teach age-appropriate financial skills to young family members | ||

Notes

- 1. Dennis Jaffe and Jane Flanagan, Three Pathways to Evolutionary Survival: Best Practices of Successful, Global, Multi-generational Family Enterprises (Chicago: Family Office Exchange and Family Business Network, 2012).

- 2. These practices are contained in the final part of the chapter, so that a family can use them for a self-assessment.

- 3. A summary can be viewed in the paper “Three Pathways to Evolutionary Survival: Best Practices for Multi-Generational Enterprise,” published by Wise Counsel, 2012.