6

brand design

If a brand is the personification of an organization or that organization’s products and services, it must have a personality and an identity. There are four major components of brand design on which you must focus once you have identified the target customer: 1) brand essence, 2) brand promise, 3) brand archetype, and 4) brand personality. Let’s begin with brand essence.

Brand Essence

Brand essence is the timeless quality that the brand possesses. It is a brand’s “heart and soul.” The essence is usually articulated in the following three-word format: adjective, adjective, noun. For instance Nike’s essence is “authentic athletic performance,” Post-it’s essence is “fast, friendly communication,” and Disney’s is “fun family entertainment.”

BRAND ESSENCE EXERCISE

When I conduct workshops on brand positioning for organizations, I always warm up the participants with an exercise that demonstrates what brand essence is. I divide the group into teams of three to four people. Each team is given five minutes to define the essence of a well-known personality. (Some people I frequently use are Madonna, Arnold Schwarzenegger, Bill Clinton, George W. Bush, John Ashcroft, Marilyn Manson, Abraham Lincoln, Albert Einstein, Adolf Hitler, Mother Teresa, Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart, and Nelson Mandela.) While there is much discussion and debate, most groups are able to agree on an essence within five minutes. The essences are always distinct for each personality assigned. (Well, almost always. In one workshop, a group defined Madonna’s essence as “audacious sexual chameleon.” Another group assigned to Bill Clinton indicated they had arrived at the same essence for him. Perhaps they were copying the adjacent group’s notes!)

Most of the essences that teams craft “ring true” with the larger group of participants in a given workshop and are fairly consistent across workshops in different organizations. The exercise reinforces the power of having a strong and well-known essence and personality.

Occasionally, brand essences take a slightly different form. Hallmark’s essence is “caring shared,” The Nature Conservancy’s is “saving great places,” and Ritz-Carlton’s is “ladies and gentlemen serving ladies and gentlemen.”

Figure 6–1 defines what a brand essence is and what it is not.

A Brand Essence Is … |

A Brand Essence Is Not… |

The “heart and soul” of the brand. |

A name. |

Elegant in its economy of words. Take one word away and it loses its meaning. |

An advertising theme line or slogan (The Nature Conservancy’s essence being a notable exception). |

A constant, timeless and enduring. It will not change over time, across geographies, or in different situations. |

A brand promise. |

Aspirational yet concrete enough to be meaningful and useful. For instance, Hallmark’s essence is “caring shared,” not “greeting cards” (a product category description that lacks the aspirational quality) or “enriching people’s lives” (aspirational but not concrete enough to be useful). |

|

Extendable. |

A product or service (category) description. |

When Xerox neared the brink of failure in the mid-2000s, its brand essence was “The Document Company,”1 which may have been one source of the company’s problems. It was a very limiting product/business description (especially in the digital age), not an extendable timeless quality.

Method’s “Our Story” section of its website says that “Eric (Ryan) knew people wanted cleaning products they didn’t have to hide under their sinks. And Adam (Lowry) knew how to make them without any dirty ingredients. Their powers combined, they set out to save the world and create an entire line of home care products that were more powerful than a bottle of sodium hypochlorite. Gentler than a thousand puppy licks. Able to detox tall homes in a single afternoon.” So, what is the brand’s essence? I think it is pretty clearly “powerful, nontoxic cleaning.”

Brand Promise

The brand promise is the most important part of a brand’s design. A brand must promise a relevant, compelling, and differentiated benefit to the target customer. (People often confuse benefits with attributes and features. The brand must promise a benefit, not an attribute or feature.) The benefit may be functional, emotional, experiential, or self-expressive. (Who am I? What do I value? What are my convictions? With whom do I associate? To what do I aspire?) Nonfunctional benefits are the most desirable, however, as they appeal to people on a visceral level and are the least vulnerable to competitive copying. The benefit must focus on points of difference, not points of parity.

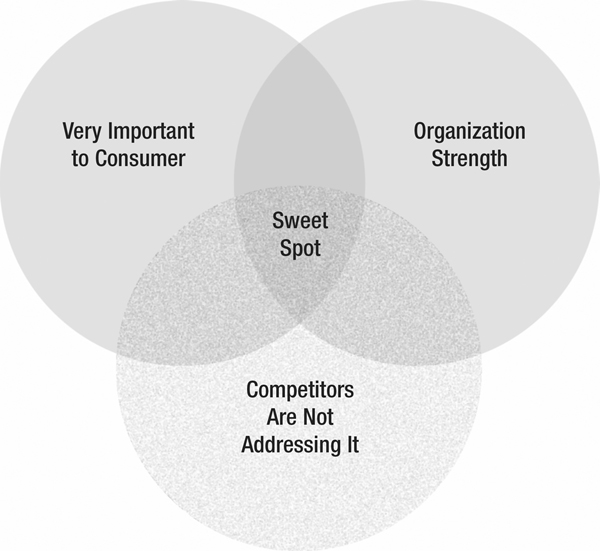

The ideal benefit has the following three qualities (see Figure 6–2):

1. It is extremely important to the target consumer.

2. Your organization is uniquely suited to deliver it.

3. Competitors are not currently addressing it (nor is it easy for them to address it in the future).

In their book Creating Brand Loyalty: The Management of Power Positioning and Really Great Advertising, Richard Czerniawski and Michael Maloney indicate that the most powerful benefits tap into people’s deeply held beliefs, exploit your competitors’ vulnerabilities, or overcome previous concerns people had about your brand, its product/service category, or its usage.2 From my experience, the most powerful benefits give people hope that they can overcome or transcend their anxieties, fears, problems, or concerns.

COMPETITIVE COPYING

The easiest thing for a competitor to copy is a price reduction or discount. Almost as easy to copy are advertised (or otherwise communicated) product and service features. The things least easy to copy are consumer benefits that are based on proprietary consumer research or behind-the-scene systems, logistics, or customer service training. For instance, if frontline service employees are trained to internalize the brand promise and are empowered to deliver it in whatever way makes sense given the situation, that is much less easy for a competitor to observe and copy. The way a company interacts with different consumers differently through database marketing is also less visible (and often highly effective).

The following steps should enable you to identify the optimal brand benefit:

• Review previous product and brand research.

• Conduct qualitative research (e.g., focus groups, one-on-one interviews) to better understand the target customer’s attitudes, values, needs, desires, fears, and concerns, especially as they relate to your brand’s product/service category. In this step, you can develop short benefit statements and run them by the target customer iteratively to get a feel for which are most compelling.

• Compile a list of twenty to forty possible benefits.

• Do research that quantifies the importance of each of the possible benefits to your target customer, together with that customer’s perceptions of how your brand and each of its competitors deliver against those benefits (to identify the most important benefits that your brand could “own”).

COMPETITIVE FRAME OF REFERENCE

Often, exploring different competitive frames of reference will help you choose the most powerful brand benefit. Here are some questions to help you determine your brand’s optimal frame of reference:

• Within what product/service category does our brand operate?

• Within which product and service categories do our customers give us “permission” to operate today? Do they give us more permission than we give ourselves?

• Does our brand stand for something broader than its products and services? Does that give our brand permission to enter new product and service categories?

• What compromises do we make with our customers that we take for granted but that might cause our customers to pursue alternative solutions to meet their needs?

• What could another company give our customers that would cause them to become disloyal to our brand?

• Could another brand within our category credibly insert its name into our brand’s promise/positioning statement?

• What are the most likely substitute products for our product?

• What could neutralize our point of difference?

• What could make our point of difference obsolete?

• What could “kill” our category?

Consider, for example, the various frames of reference from which Coca-Cola could choose, from most narrow to most broad (see Figure 6–3).

Figure 6–3. Frames of reference for Coca-Cola.

Frame of Reference |

Potential Competitors |

Potential Point of Difference |

Cola |

Pepsi, RC Cola |

? |

Carbonated beverage (soda pop) |

7 Up, Dr. Pepper |

? |

Soft drink |

Crystal Light, Gatorade |

? |

Nonalcoholic beverage |

Chocolate milk, root beer float |

? |

Beverage |

Wine, beer |

? |

Liquid refreshment |

Water, bottled water |

? |

Psychological refreshment |

A walk in the woods, yoga, a swim |

? |

Now consider how Hallmark Cards’ “differentiating benefits” might vary for each of the frames of reference listed in Figure 6–4.

Figure 6–4. Frames of reference for Hallmark Cards.

Frame of Reference |

Potential Product Categories |

Greeting cards |

Greeting cards |

Social expression products |

Note cards, invitations, electronic greetings, enhanced e-mail |

Caring and sharing |

Flowers, candy, gift baskets, romantic cruises, family portraits, family scrapbooks, children’s books, children’s educational activities, family games, massage oil |

Community building |

Interpersonal relationship workshops, marriage enrichment courses, planned communities |

And, interestingly, Cirque du Soleil did not define its competition as “other circuses,” but rather as “every other show in town.”3

Find out how choosing alternative frames of reference will alter competitive sets, products and services, and points of difference. Broadening your brand’s frame of reference can help you:

1. Identify a strong point of difference within your current narrower frame of reference. (For instance, Pepsi chose to “own” psychological refreshment as a point of difference over Coca-Cola.)

2. Identify logical avenues for brand growth.

3. Identify potential substitute products and other competitive threats.

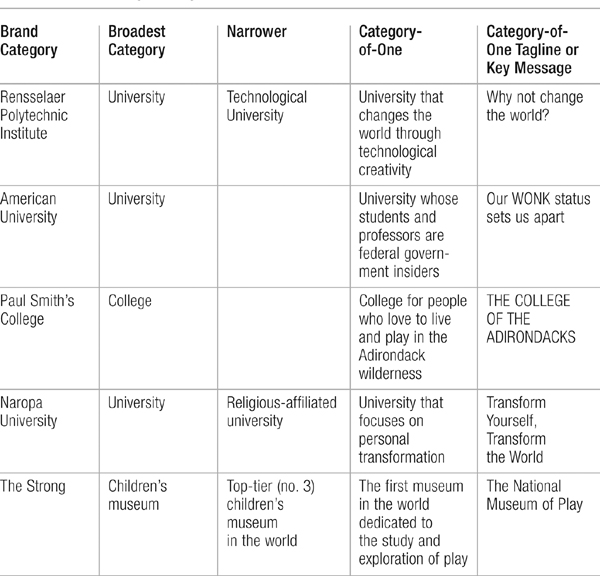

To create a “category of one” brand, one must choose a preemptive frame of reference so that the brand is the only one in its consideration set. Rather than differentiating the brand by choosing a differentiating benefit within a current product/service category or frame of reference, one differentiates the brand by identifying or creating an entirely new product/service category or frame of reference that is highly compelling. The new category is set up so that the brand in question is the only one within that category (Figure 6–5).

For the sake of simplicity and focus, I state a brand’s promise as follows:

Only [brand] delivers [relevant differentiated benefit] to [target customer].

Use of the word only is very important. It forces you to choose a benefit that only your brand can deliver.

Occasionally, clients will ask why they can’t craft the brand promise as, “[Brand] is the best at delivering [relevant differentiated benefit] to [target customer].” The problem with this approach is that being the best may not change a customer’s purchase behavior if other brands deliver against the chosen benefit to a sufficient degree.

Others may use a form that incorporates the frame of reference, such as “Only [brand] delivers [relevant differentiating benefit] to [target customer] within the [product/service category].” Although the frame of reference exercise can help to identify potentially powerful differentiating benefits, incorporating it into the brand promise itself is not helpful. Here are some brand promises of well-known brands (see also Figure 6–5):

• Only Volvo delivers assurance of the safest ride to parents who are concerned about their children’s well-being.

• Only Harley-Davidson delivers the fantasy of complete freedom on the road and the comradeship of kindred spirits to avid cyclists.

• Only The Nature Conservancy has the expertise and resources to work in creative partnership with local communities in the United States and internationally with exceptional range and agility to conserve the most important places for future generations.

• Only the Boy Scouts of America instills values in boys, resulting in a more successful adulthood on a massive nationwide scale through a proven fun program.

A brand promise must be (and should be tested to be):

• Understandable

• Believable

• Unique/Differentiating

• Compelling

• Admirable or Endearing

Once crafted and agreed to, the brand promise should be delivered at each point of contact with the consumer. So everyone in your organization should know your brand’s promise.

VOLVO BRAND STRATEGY

In the late 1990s to mid-2000s, Volvo Car executives believed the brand position of the “ultimate safe car” for families was too limiting and began to extend the brand into the performance car segment targeted at men. Results were disappointing. When Ford bought Volvo in 1999, it pushed the brand into the crowded luxury brand market. Ten years later, sales were down 20 percent from where they were when Ford first purchased the brand.

Volvo Car Corporation was then acquired by China’s Zhejiang Geely Holding Group Co. Under this new ownership, in August 2011, Volvo Car announced a new global brand strategy—“Designed Around You,” focusing on a position of human-centric luxury cars that are safe and dependable.

In November 2013, Volvo Car Corporation announced a new brand strategy designed to revive the brand in the United States after a decade of declining demand. According to Automotive News, “The new focus is on ‘Scandinavian’ design, safety, environmental leadership, and ‘clever functionality’ reflected in state of the art—yet simple—infotainment systems.”

Volvo’s primary brand association is still “safety.” And safety is still most valued by parents with children living at home. And Volvo is still one of the most trusted automobile brands. Any repositioning must be congruent with and build on its reputation as the “ultimate safe car.”

Sources:

David Kiley, “Volvo Goes Beyond Safety” Bloomberg Businesssweek, March 22, 2007, www.businessweek.com/stories/2007-03-22/volvo-goes-beyond-safetybusinessweek-business-news-stock-market-and-financial-advice.

Patrick Lefler, “Is Volvo’s New Brand Strategy Going to Stress Luxury or Safety?” Customer Think (blog), August 19, 2010, customerthink.com/is_volvo_s_new_brand_strategy_going_to_stress_luxury_or_safety/.

“Volvo Car Corporation Announces a New Brand Strategy—Designed Around You,’” company news release, August 23, 2011, www.volvocars.com/intl/top/corporate/news/pages/default.aspx?itemid=307.

Richard Truett, “Volvo Outlines Strategy for U.S. Revival,” Automotive News, November 7, 2013. www.autoweek.com/article/20131107/CARNEWS/131109872.

Brand Archetype

Whereas the brand personality uses adjectives to describe the brand as if it were a person, the brand archetype, based on Jungian archetypes, indicates the brand’s driving force or motivation. Margaret Mark and Carol Pearson, in their book The Hero and the Outlaw: Building Extraordinary Brands Through the Power of Archetypes, describe twelve archetypes in great detail—the innocent, the explorer, the sage, the hero, the outlaw, the magician, the regular guy/gal, the lover, the jester, the caregiver, the creator, and the ruler. We use twenty-seven different archetypes when we work with clients.

As an example, in Winning the Story Wars, Jonah Sachs describes the defender archetype as “defending that which is sacred but may be lost.” The archetype’s qualities are “strong, sensitive, selfless, and resolute” and its values are “justice, perfection, and wholeness.” Famous defenders include “John Muir, Jane Goodall, Ronald Reagan, the Tea Party, Greenpeace, and the Boy Scouts.” He says that “while defenders are indespensible in any society, they are often the last to accept needed change.”4

Brand Personality

Each brand should choose an intended personality based on the brand’s aspirations and its customers’ current perceptions of the brand. The personality is usually communicated in seven to nine adjectives describing the brand as if it were a person.

A brand’s personality and values are often a function of the following:5

• The personality and values of the organization’s founder (assuming the person had a strong personality and values)

• The personality and values of the organization’s current leader (again, assuming this individual has a strong personality and values)

• The personalities and values of the organization’s most zealous customers/members/clients

• The brand’s carefully crafted design/positioning

• Some combination of the above

Although personality attributes vary considerably by product category and brand, strong brands tend to possess particular personality attributes. In general order of importance, strong brands are:

• Trustworthy

• Authentic

• Reliable (“I can always count on [brand name]!”)

• Admirable

• Appealing

• Honest

• Representative of something (specifically, something important to the customer)

• Likable

• Popular

• Unique

• Believable

• Relevant

• Known for delivering high-quality, well-performing products and services

• Service-oriented

• Innovative

Employees are also an important factor in communicating the brand’s personality in organizations in which the organizational brand is used. This is why companies are increasingly recruiting, training, and managing their employees to manifest their brands’ promises.

Repositioning a Brand

Brand repositioning is necessary if one or more of these conditions exist:

• Your brand has a bad, confusing, or nonexistent image.

• The primary benefit your brand “owns” has evolved from a differentiating benefit to a cost-of-entry benefit. (For example, for airlines cost-of-entry benefits would be safe flights, needed routes, and required times.)

• Your organization is significantly altering its strategic direction.

• Your organization is entering new businesses and the current positioning is no longer appropriate.

• A new competitor with a superior value proposition is entering your industry.

• Competition has usurped your brand’s position or made it ineffectual.

• Your organization has acquired a very powerful proprietary advantage that must be worked into the brand positioning.

• Corporate culture renewal dictates at least a revision of the brand personality.

• You are broadening your brand to appeal to additional consumers or consumer need segments for whom the current brand positioning won’t work. (This should be a “red flag” since it could dilute the brand’s meaning or make it less appealing to current customers or even alienate them.)

You follow the same steps and address the same brand design components when repositioning a brand as you do when first designing the brand. But brand repositioning is more difficult than initially positioning a brand because you must first help the customer “unlearn” the current brand positioning (easier said than done). Three actions can aid in this process:

1. Carefully crafted communication

2. New products and packaging that emphasize the new positioning

3. Associations with other brands (e.g., cobranding, comarketing, ingredient branding, strategic alliances) that reinforce the new brand positioning

You should not rely on an advertising agency, a brand consulting company, or your marketing department to craft your corporate or organizational brand’s design. This is so critical to your organization’s success that its leadership team and marketing/brand management leaders should develop it themselves, preferably with the help of a brand positioning expert.

REBRANDING FOOTJOY

FootJoy is a well-known golf brand (67 percent of golfers use it) recognized for having comfortable, exceptionally high-quality products that stay dry in wet conditions. FootJoy sells shoes, gloves, outerwear, socks, and accessories.

Traditionally, FootJoy focused is messages on its superior product features and functionality; however, it knew it needed to create a more emotional connection with its customers. FootJoy retained us to help create this emotional connection. Through qualitative research, we learned that FootJoy was perceived to be a golf-centric brand that is for people who are serious about golf. We discovered that it had the potential to be a strong aspirational brand as it possessed all the qualities to which serious golfers aspire. The result was a new tagline (The Mark of a Player) that underpinned a new advertising campaign, making FootJoy a badge that says, “I am a serious golfer.”

Conducting a Brand Positioning Workshop

Frequently, a brand design is not embraced by the organization because the leadership team was not actively involved in the process at every step along the way. Often, outside experts will design a brand based on separate interviews with key stakeholders. This input does not allow for disagreement, debate, discussion, or consensus building among the stakeholders. Brand positioning involves highly facilitated, well-prepared sessions in which all the key stakeholders (typically organization leaders and marketing executives) are “locked in a room” until they reach a consensus on all the key elements of brand design: the target customer and the brand essence, promise, archetype, and personality. Figure 6–6 is the brand positioning statement template that we use in our brand positioning workshops.

Figure 6–6. Brand positioning statement template.

Brand Essence

[Adjective] [adjective] [noun] (the “heart and soul” of the brand, its timeless quality, its DNA)

Brand Promise

Only [brand]

Delivers [unique and compelling benefit or shared value]

To [target customer description]

In the [product or service category] (establishing the competitive “frame of reference”)

In the context of [market condition or trend that makes the benefit or value even more compelling]

Because [proof points or “reasons to believe”]

Brand Archetype

Choose one or two archetypes (what drives or motivates the brand, as related to Jungian archetypes).

Brand Personality

Choose six to ten adjectives that describe the brand as if it were a person.

If the brand is an organizational brand, we also specify the brand’s (organization’s) mission, vision, and values.

Taken together, these elements of the brand positioning statement should inform all brand decisions and its communication strategy and become important components of creative briefs.

BRAND POSITIONING CASE STUDY:

Element K

I became the vice president of marketing at Element K, a leading e-learning company, in September 2000. Earlier that year, U.S. Equity Partners acquired ZD Education from Ziff Davis and renamed it Element K. Element K has four business units: Element K Online (e-learning), Element K Courseware (computer training courseware publishing), Element K Journals (journal publishing), and Element K Learning Center (Rochester, NY–based computer training center).

When I joined Element K, there was virtually no awareness of the brand by our target customers: corporate chief learning officers. And we intended to take the company public after the turbulent market of late 2000 stabilized. My objective was simple: to quickly and aggressively build brand awareness and differentiation to make Element K the number one preferred e-learning brand.

When I was at Element K, the e-learning market was an increasingly crowded space with hundreds of relatively new companies vying for a greater share of the market and industry leadership. Since then, the market has grown rapidly and consolidated considerably. In 2013, the e-learning market is worth $23.8 billion in the U.S. alone, while the learning management system (LMS) space is about $2.55 billion, of which Skillsoft has a $414 million share. Worldwide, the e-learning market is projected to grow to $51.5 billion by 2015.

This growth is fueled by the many advantages that e-learning offers vis-à-vis traditional classroom training:

• There is great flexibility in where and when to train.

• People can learn at their own pace.

• E-learning is especially effective for decentralized organizations with geographically dispersed workforces.

• You can train an unlimited number of employees.

• Training is “on demand,” decreasing cycle time significantly.

• E-learning is a fraction of the cost of classroom training.

Element K’s e-learning solution is fully hosted on the Internet. We had large up-front fixed costs associated with developing our instructional design methodology, 800+ online courses, and a robust learning management system. But variable costs were low: Providing access to our e-learning solution was as simple as giving someone an ID for access to the site. The cost of adding servers was almost the only variable cost (cost that increases with increased usage/volume). For this reason, we increasingly focused on delivering enterprisewide solutions to Fortune 1000 companies and similarly large organizations in which the number of users was substantial with each sales agreement. Simply put—our business model favored large numbers of students.

Most of the companies vying for business in this segment of the e-learning space, if they even had any semblance of consistent messaging, directed one of the following messages at corporate officers:

• We offer a complete, integrated solution.

• Our e-learning can improve your organization’s performance. It produces good business results.

• High-profile clients are very pleased with our solution.

Every company seemed to be saying the same things, and there was way too much clutter to break through. We therefore embarked on qualitative and quantitative research to identify the key decision makers and the most powerful differentiating benefit for Element K to own. In our qualitative research (one-on-one interviews and mini-groups) we found that the primary decision maker is the senior-most executive with enterprisewide training responsibility, often bearing the title of CLO (chief learning officer). In this research, we also explored people’s needs, desires, fears, concerns, and other perceptions regarding training in general and e-learning in particular. From that, we developed thirty-three different brand benefit statements, which we reviewed with people toward the end of each session. We added, eliminated, and revised statements after each round of feedback. In the process, we gained a major insight, which led to Element K’s brand positioning: People have an underlying concern that, despite all of its potential advantages, e-learning lacks the human touch. In particular they were concerned that, with e-learning:

• You lose the personal attention only an instructor can offer.

• It is harder to ask questions.

• Feedback is not possible.

• Students may feel isolated.

• You lose peer-to-peer learning.

• There is no peer pressure to attend or complete the course.

• There is not enough personal attention available.

Based on insights from the qualitative research, we developed quantitative research to measure the importance of the wide variety of brand benefits to the target customer. This research also quantified each brand’s perceived delivery against each benefit. In this way, we were able to identify the most important benefits and the benefits for which Element K had the biggest relative (and absolute) advantage.

While several benefits were higher in importance, all of them were benefits that would quickly become “cost of entry” benefits (such as affordable price, quality content, and ease of use). E-learning with the human touch was validated to be important. More important, it provided Element K with the biggest advantage. While two-thirds of the respondents believed that Element K integrates the human element into e-learning, only one-third and one-quarter, respectively, believed Element K’s two primary competitors did the same (see Figure 6–7).

This benefit was particularly powerful for Element K to “own” for the following reasons:

• It addresses one of the major fears about e-learning. (Fear is a particularly powerful motivator.)

• Element K had a substantial advantage in this area, according to the research.

• Element K delivered on this promise at multiple levels, including:

- The way the student experience was designed.

- The way the training administrator experience was designed.

- Its comprehensive support services.

- Its participation management services.

- The way the salespeople interact with customers (friendly, low pressure, consultative selling).

- Within the corporate culture itself. (Element K is naturally service-oriented, which is sustainable because it is built into the corporate DNA.)

• Element K’s most formidable competitor was generally known to be pushy and arrogant and only interested in “making the sale.” (This was a part of the firm’s corporate culture.) This positioning would indirectly and subtly bring this weakness to mind.

• Element K’s customers found the company to be very easy to work with. (There was extensive anecdotal evidence that Element K had won many contracts based on this fact alone.)

• It felt “right” and was quickly embraced by every employee.

Here is what we now say about Element K:

Element K brings a unique understanding of how people learn to the business of training. Our understanding comes from a twenty-year heritage of innovation in adult career learning for leading corporations. Today, you’ll find it in our best-in-class e-learning solution—over 800 courses integrated with a state-of-the-art learning management system, all delivered with a human touch.

This statement is believable because of Element K’s rich heritage as a company of training professionals, founded by two university professors who wanted to make adult training more interesting and interactive. As training professionals committed to multiple training modalities (including classroom instruction), Element K would want to share and address these concerns. The company is now committed to building “the human touch” into everything it does, from the way the sales force interacts with potential customers and the services offered to current customers, to the enhancements made to our learning management system and the personality characteristics looked for when hiring new employees.

SELF-IMAGE AND BRANDING

Most people view themselves in the context of a wide variety of identity elements:

• Race/ethnicity

• Gender

• Sexual orientation

• Age

• Intelligence

• Physical characteristics

• Health

• Fitness

• Attractiveness

• Personal values

• Personality attributes

• Competencies/talents

• Vocation

• Avocations/hobbies

• Religious beliefs

• Nationality

• Place of residence

• School affiliations

• Political party affiliation

• Other organizational affiliations

• Income level

• Wealth level

• Social class

• Peer or social group affiliation

Many of the identity elements interact with and reinforce (or conflict with) one another. People often emphasize the elements that are the most advantageous in a given context. Each of these identity elements contributes to a sense of self, and each could be an entry point for brand alignment and self-image reinforcement.

Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute

Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute, founded in 1824, was the first degree-granting technological university in the English-speaking world. Rensselaer was established “for the purpose of instructing persons, who may choose to apply themselves, in the application of science to the common purposes of life.” Since Rensselaer’s founding, its alumni have impacted the world in many significant ways, including:

• Inventing television

• Creating the microprocessor

• Managing the Apollo project that put the first man on the moon

• Founding Texas Instruments/creating the first pocket calculator

• Creating e-mail (including using the @ symbol)

• Inventing baking powder

• Inventing the Reach toothbrush

• Building the Brooklyn Bridge

• Building the Panama Canal

• Inventing the Ferris wheel

Yet, for all of its accomplishments, in the late 1980s and early 1990s, Rensselaer was not well positioned (to prospective students) compared with its world-renowned rival, MIT, or even schools such as Caltech, UC Berkeley, and Carnegie Mellon. Many state universities (e.g., Purdue, University of Illinois at Urbana, etc.) offered exceptionally strong technical programs at significantly lower costs than private universities. Ivy League schools and other first-tier liberal arts universities were building their math, science, and engineering programs. And most states had public universities that provided respectable engineering programs. This increasingly competitive landscape left Rensselaer in a positioning “no-man’s-land.” I was on Rensselaer’s alumni board of directors and national admissions committee at the time. We worked with the school to conduct research to better understand the college selection process. We interviewed students (and their parents), some of whom chose to attend Rensselaer and some of whom didn’t. We explored what factors were most important in their decision-making process as well as their perceptions of Rensselaer as compared with other schools. And we conducted focus groups with alumni and businesspeople to better understand their impressions of Rensselaer.

Almost everyone who knew of Rensselaer perceived it to be a first-rate technical school. Many put it in the same class as MIT. People “in the know” were genuinely impressed with the school and the caliber of its students, its academics, and its research. But there were drawbacks:

• Rensselaer is in Troy, New York (which lacks the appeal of, say, Boston or California).

• Rensselaer is not as well known or prestigious as MIT. It does not have the same name cache.

• Rensselaer costs more than state engineering schools (though after factoring in financial aid, costs can be comparable).

• Rensselaer was known to be a “boot camp.” It’s been said that “you don’t go there to have fun.”

• The curriculum was perceived to be too narrow compared with liberal arts schools.

• The school had a lopsided male to female ratio (13:1 when I attended in the mid-to-late 1970s, and a 3:1 ratio today).

• A significant portion of Rensselaer’s students (mostly those who had used Rensselaer as a backup school to MIT and others) felt inferior to students at their first-choice schools.

Furthermore, those with no connection to the school had no impression of the school. Awareness was also nil among the general U.S. population.

These were significant hurdles. And yet, looking at the school itself, there were also a number of very strong advantages, which include:

• A rich history by alumni of major contributions to society

• A vital, engaged campus community

• A strong student leadership development program

• Innovations in entrepreneurship, with one of the first and perhaps best known business incubators and a strong student entrepreneurship program

• Award-winning innovations in educational techniques

• Thriving interdisciplinary research centers

• Programs that ranked among the best available in the world

• An increasingly strong reputation throughout the world

(Interestingly, the university’s reputation was stronger in many other countries than it was in the U.S. Midwest!)

Also, the university had embarked on a significant long-term commitment to enhance the student experience, addressing everything from administrative procedures, counseling, and breadth of course offerings to quality of instruction, the male-to-female ratio, and campus aesthetics. And, gauging from student surveys over time, the efforts were producing significant results.

Here are the key insights that led to Rensselaer’s very powerful current positioning:

• Rensselaer’s students have always been serious about their chosen fields of endeavor and their studies.

• Rensselaer’s faculty, students, and alumni want to make a difference in the world.

• Rensselaer is and has been a leader in technological innovation.

• Rensselaer’s alumni, throughout the school’s history, have made major, lasting contributions to society.

• Rensselaer was emerging as a leader in entrepreneurship, especially technological entrepreneurship.

• “Technological creativity” seemed to capture the essence of the school and the spirit of those associated with the school throughout its now 190-year history.

• Rensselaer wanted its new positioning not only to capture the school’s unique competitive advantages, but also to inspire its students and give them confidence. (In the mid-to-late 1970s, under George Low’s leadership, the school informally adopted the slogan, “Rensselaer: Where imagination can achieve the impossible.” For a short time after that, the school used the slogan, “Rensselaer: For minds ahead of their time.”)

So, Rensselaer’s tagline—“Why not change the world?”—was born.

Confident? Yes.

Aspirational? Yes.

Inspirational? Yes.

Accurately reflecting the school’s strengths and those of its alumni? Yes.

An invitation to like-minded individuals and organizations to “come join Rensselaer in its quest”? Yes

Effective in recruiting an increasing number of highly qualified students? Yes.

Rensselaer’s entering freshman classes are the most qualified and talented in the last few decades. Each class seems more qualified than the one before. As one measure, the class of 2005 arrived on campus with an average SAT score of 1307, 25 points over that of the previous class. And in the three years between 2005 and 2008, applications went from 5,500 to 11,000. In 2013, more than 16,100 high school students applied for admission to Rensselaer and the average SAT critical reading and math score for the admitted group averaged 1408.

And the most important question: Are students satisfied with Rensselaer and its recently articulated positioning? Yes.

Today, Rensselaer is thriving. In early 2001, it received a gift of $360 million—the largest single gift (at that time) ever made to a university. In 2004 it built a $82 million Center for Biotechnology and Interdisciplinary Studies to expand its research portfolio; in 2008 it built a $200 million Experimental Media and Performing Arts Center to showcase its world-leading electronic arts program; in 2009 it built a $92 million East Campus Athletic Village; and in 2013 it established its $100 million Computational Center for Nanotechnology Innovations (CCNI), featuring the seventh most powerful supercomputer in the world.

CASE STUDY:

GEICO Direct Insurance

When BrandForward conducted its insurance industry brand equity study, it uncovered a few things about the insurance industry:

• The insurance industry is highly fragmented. While there are dozens of companies whose names consumers recognize, less than a handful receive significant unaided first mention.

• While there is high behavioral loyalty, there is low attitudinal loyalty.

• Consumers have a low emotional connection to insurance brands.

• Fewer than one in five people said that their insurance company “has never disappointed them.” (One sign of emotional connection.)

• Although consumers perceive differences among insurance companies, they don’t perceive those differences to be significant. Price and rates are among the most important points of difference between companies, suggesting the category is commodity-like for many consumers.

• The following are the most important consumer benefits in the insurance industry. Of these benefits, consumers perceive only two of them to be addressed to any large degree:

- Paying claims fairly and promptly

- Good rates/prices

- Honest, trustworthy representatives

- Accessible, available representatives

- Knowledgeable, competent representatives

- Easy-to-understand policies

- Financial stability of company

• The following benefits have the widest variation in delivery and therefore provide the greatest opportunities for differentiation:

- Representatives who provide unbiased recommendations (all insurance categories)

- Good rates/prices (all categories)

- Knowledgeable, competent reps (life insurance)

- Honest, trustworthy reps (life insurance)

- Ability to establish a personal relationship (home and auto insurance)

- Strong overall reputation (financial services)

• The sales representative’s and claims adjuster’s points of contact with consumers are critical to the success of insurance company brands.

• The most brand preference exists in the auto insurance category (roughly a third with “no preference”), and the least brand preference exists in the financial services category (two-thirds with “no preference”).

• At the time, State Farm was the preferred brand by a wide margin (especially in home and auto insurance). It also has a wide lead in the emotional connection it has created with consumers.

• GEICO was an “up-and-coming” brand in auto insurance (see Figure 6–8).

• Prudential was the preferred life insurance brand.

While State Farm seemed to be doing many things right, almost all the other insurance companies seemed to lack any significant brand equity. But this story is not about State Farm. It’s about GEICO Direct, at the time a virtually unknown auto insurance brand. And this is a very simple, short story: GEICO began to advertise its brand at a level that was the talk of the industry. And its message was very simple: “You could save 15 percent or more on car insurance!” (See Figure 6–9.)

In brand building, focus is everything, and GEICO focused on one product segment—auto insurance—and one benefit—low price. And it did so again and again and again with a disciplined consistency. And its brand equity and market share increased at rates unknown to other insurance brands. In an industry with little brand equity or differentiation, GEICO decided to build its brand by aggressively focusing on an important brand benefit: low price. Its success was that simple—and consistent enough so that its current campaign focuses on the fact that “everyone knows” that “15 minutes can save you 15 percent or more on car insurance.” (In general, I would not recommend trying to own “low price” as a point of difference. Typically, it is not a sustainable point of difference. Nor does it usually contribute to building brand equity. Given where the insurance industry was when GEICO launched its campaign, it was an effective entry point from which to eventually add other messages.

REPOSITIONING RCI

Part of Wyndham Worldwide, RCI is a global leader in vacation time-share exchange networks. Interval International is its primary competitor. While smaller than RCI, Interval International had successfully positioned itself as the “quality” vacation timeshare exchange network. RCI retained us to help reposition the RCI brand. After poring over the research, it became clear that the category’s primary benefit is choice. People who invest in timeshare exchange networks do so to expand their choices. It also was clear that RCI offered significantly more choices in more places around the globe. Furthermore, RCI offered many more different types of properties not available through competitors. We helped the company see that “maximum choice” was the benefit to own in the industry and that it had unmatched proof points against this claim. We knew that “maximum choice” would trump “a smaller number of high-quality properties” for most people (and affiliated resorts) when selecting a vacation timeshare exchange network (partner). We also worked with RCI to identify ways to expand the company’s choices and to rectify system and process barriers to offering greater choice.

Use the checklist in Figure 6–10 to assess the efficacy of your brand management practices in the area covered by this chapter. The more questions to which you can answer “yes,” the better you are doing. The checklist also provides a brief summary of the material covered in the chapter.

Figure 6–10. Checklist: Brand design.