18

brand equity measurement

ACCORDING TO A well-known axiom, you can’t manage what you don’t measure. This is true of brand equity as well. Any strong brand equity measurement system will accomplish the following objectives:

• Measure the brand’s equity across a variety of dimensions at different points in time over time.

• Provide diagnostic information on the reasons for the changes in brand equity.

• Gauge and evaluate the brand’s progress against goals.

• Provide direction on how to improve brand equity.

• Provide insight into the brand’s positioning vis-à-vis its major competitors, including its strengths, weaknesses, opportunities, and threats.

• Provide direction on how to reposition the brand for maximum effect

When I was named director of brand management and marketing at Hallmark, I was given two primary objectives: 1) to increase Hallmark market share and 2) to increase Hallmark brand equity.

Market share is a relatively straightforward objective for which we already had metrics. Brand equity was much less well defined. I spent the better part of the next three years drawing upon the knowledge of various consultants, researchers, and scholars and dozens of different brand equity models to define brand equity in a way that was useful to Hallmark. To be useful to Hallmark, it had to show how to move people from high brand awareness to brand insistence. Since then, this work has resulted in a validated and refined measurement system that is used by scores of organizations across dozens of industries.

Components of a Brand Equity Measurement System

Here are the components that a brand equity measurement system should measure:

• Brand awareness (first mention, or top-of-mind unaided recall, and total unaided recall)

• Brand preference

• Brand importance/rank in consideration set

• Brand accessibility

• Brand value (quality and value perceptions and price sensitivity)

• Brand relevant differentiation (open-ended question and perceptions on key attributes)

• Brand emotional connection

• Brand vitality

• Brand loyalty (multiple behavioral and attitudinal measures, including share of requirements/wallet)

• Brand usage

• Brand imagery (against a standard battery of category-independent brand personality attributes proven to drive brand insistence, and a customized battery of brand personality attributes for the particular organization and its product/service category)

Most Important Brand Equity Measures

The most important brand equity measures are:

• Unaided brand awareness, especially first recall.

• Remembered/recalled brand experience.

• Knowledge of the brand’s promise.

• Brand’s position in the purchase consideration set.

• Brand’s delivery against key benefits. (We have found two separate approaches to be insightful: mapping benefit importance against brand benefit delivery—a scaled response—and an open-ended question, “What makes brand XX different from other brands in the YY category?”)

• Emotional connection to the brand.

• Price sensitivity.

• Relative accessibility.

Specific Brand Equity Measures

What follows is a list of specific questions and measures that will help you manage a brand’s equity:

• Brand Awareness:

- What is the first brand that comes to mind when thinking about the xxx category?

- What other brands come to mind for the xxx category?

• Brand Preference:

- Which brand (of product category) do you prefer? (The incidence of those with no brand preference can also provide insights into the importance of brand in the category.)

• Brand Usage:

- Which brand (of product category) do you most often use?

• Brand Accessibility:

- Widely available.

- Easy to find and purchase.

• Brand Value:

- Quality perception.

- Value perception.

- Price sensitivity.

• Brand Relevant Differentiation:

- What makes brand xxx different from other brands in the yyy category?

- What one or two things make (category) brands different from one another?

- Which brand or brands (of product/service category) do you prefer when you are looking for the (relevant differentiated) benefit?

- Which brand (of category) best meets your needs? Why?

- How well does the xxx brand deliver against the yyy benefit? (Rated on a five-point scale.)

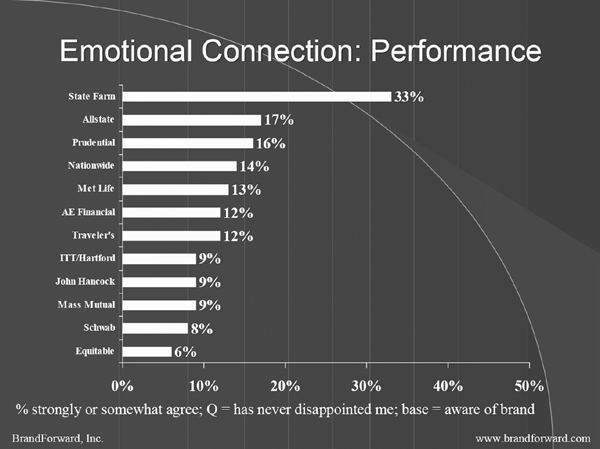

• Brand Emotional Connection:

- Your brand is almost like a friend to your customers.

- It stands for something important to them.

- It says something about who they are.

- It has never disappointed them (see Figure 18–1).

• Brand Loyalty:

- Share of requirements/share of wallet.

- Share of last ten purchases. (Constant sum questioning works best. Questions about the “brand most often purchased” or “brands bought in the past six months” almost always overstate purchases for well-known brands and understate purchases for low-price brands.)

- Satisfaction.

- Willingness to recommend to a friend.

- Deal sensitivity.

- Switching propensity.

A particularly telling question is, “Describe your most memorable recent interaction with [brand].” Such an open-ended question provides insight regarding the source of interaction (touchpoint), quality of interaction, and intensity of interaction.

LADDER OF THE MIND (Consideration Set Continuum: 7-Point Scale)

1. I would never choose to buy this brand.

2. I’ve never heard of this brand.

3. I’ve heard of this brand but don’t know much about it.

4. Not one of my preferred brands, but I’d try it under certain circumstances.

5. Not one of my preferred brands, but from what I’ve heard about it recently I’d like to try it/try it again.

6. This is one of my preferred brands.

7. This is the only brand I would ever consider buying.

(Source: Transcript Proceedings: “Tracking the Obvious: New Ways of Looking at Old Problems” by Martin Stolzenberg, President, Stolzenberg Consulting, and Peggy Lebenson, Senior Vice President, Data Development Corporation. “Advertising and Brand Tracking: The Power of Today’s Advertising and Brand Tracking Studies: An Advertising Research Foundation Key Issues Workshop,” November 12–13, 1996, New York, Grand Hyatt Hotel, copyright 1997 by Advertising Research Foundation.)

• Brand Vitality. Design marketing campaigns to build perceived brand momentum:

- Are you hearing more about the brand lately?

- Is the brand changing for the better?

- Which brand is reinventing the category?

- Which brand, in your opinion, will lead the industry four years from now?

• Brand Consideration Set:

- How many other brands are in the consideration set?

• Brand Personality:

- Popular.

- Trustworthy.

- Other (e.g., innovative, dependable, contemporary, old-fashioned, practical, boring, fun).

A SAD DAY

It is a sad day when a previously meaningful and vibrant brand is taken over by or combined with a new entity that does not share the brand’s essence, promise, and values. This happens quite often, with mergers and acquisitions, when a company is taken private or public, or with other changes in ownership or leadership. Sometimes it happens when a financial owner (such as a venture capital firm) replaces the previous management team with its own new team. This is particularly true when people who only understand one thing, ROI (or, more specifically, their personal financial gain), replace the leadership team that had the original brand vision. We saw this happen when General Motors took control of Saturn, losing Saturn’s “different kind of company” operating philosophy and forcing it to run like any other GM brand. Likewise, Compaq once owned 20 percent of the personal computer market, but mismanagement of the brand after Hewlett-Packard acquired it eventually resulted in its complete demise.

Such a change is akin to a person’s spirit exiting his or her body to allow a new spirit to inhabit it. While the newly combined physical/spiritual entity may seem to be the same entity as before, new attitudes and behaviors will eventually betray the new spirit, but not until after the huge reservoir of brand equity is traded for short-term financial gains for the new owners. This is one reason previously strong brands seem to “lose their way.”

What a Robust Brand Equity Measurement System Must Have

A robust brand equity system should include all the measures listed previously. It should be tailored to a particular company and industry. (At a minimum, the competitive set, personality attributes, and category benefit structure will vary by industry. Ways of measuring value and loyalty typically also vary by industry.) The measurement system should also include behavioral and attitudinal measures, especially for brand loyalty. Through regression analysis and other techniques, the system should determine attitudinal measures that best predict brand loyalty and other desired behaviors (predictive modeling). The system should be capable of analyzing brand equity by category or customer segment if required. Comparing results of frequent users, occasional users, and nonusers also provides useful insights. It is important to measure brand vitality because purchase intent is almost always overstated for well-known, well-regarded older brands with waning differentiation (i.e., declining brands) and understated for newer brands with low awareness but high relevance and differentiation (i.e., emerging brands). Brand vitality can help adjust for this variance.

Robust brand equity systems also deliver these beneficial features:

• A visual portrayal of positioning opportunities and vulnerabilities, such as mapping attribute/benefit importance against brand delivery (see Figure 18–2).

• Comparisons to other industries (from a normative database) to identify additional opportunities and vulnerabilities.

• Identification of natural customer clusters.

• Demographic/lifestyle analysis and profiling.

Common Problems with a Brand Equity Measurement System

The most common problems include the following:

• The system from which to manage brand equity is too simplistic (e.g., those omnibus studies that measure only two to four dimensions of brand equity, such as awareness or favorability).

• No competitive comparisons are included in the measurement. (Many companies measure against themselves by, for instance, measuring customer satisfaction improvements. A brand equity measurement system must include competitive comparisons. By definition, brands are positioned against other brands. And few customers compare you against yourself. Most customers compare you with other companies and brands. Competitive context is not only highly insightful—it is critical to managing your brand’s equity.)

• The sample size is too small to provide for valid subgroup analysis.

• The sample size is too small to detect small changes in brand equity in the shorter term.

• Customers are surveyed too frequently. Typically, it is sufficient to measure brand equity once a year, unless one of the following conditions exist:

- The brand is new.

- You have repositioned the brand or otherwise altered the brand communication or delivery in a major way.

• You make use of the organization’s own customer and/or prospect list so that brand awareness, usage, and other measures are not projectable to the general population.

• The survey is designed in a way that biases the unaided brand awareness question—rendering the results of that question invalid.

• Organizations are unable to identify a primary product category or set of competitors because of the uniqueness of their brand or the lack of a brand unifying principle. This eliminates some of the most important brand equity measures (top-of-mind awareness, brand differentiation, etc.) from the measurement system.

• A tailored set of brand/category benefit statements is not included in the study. These statements must come from a rigorous understanding of the category benefit structure, typically identified by prior qualitative customer research dedicated to the purpose of identifying that structure.

• The organization confuses other studies with a brand equity measurement system. Mostly, people believe that customer satisfaction studies, attitude and usage studies, and corporate image studies are the same as brand equity measurement systems (or viable substitutes for them).

Assessing the Effectiveness of an Organization’s Brand Equity Measurement System

Brand equity measurement systems are the most effective when clients can answer each of the following questions affirmatively:

• Do you have a profound understanding of your brand’s consumers?

• Do you know what drives your brand’s equity?

• Have you established and validated equity measures for your brand?

• Have you set objectives against these measures?

• Do key decision makers regularly see results against these objectives?

• Are people held accountable for achieving brand objectives?

Brand Equity Should Not Be Measured Just for Customers

Businesses should also monitor their brand equity with certain groups (in addition to their customers). These groups include:

• Industry analysts

• Financial analysts

• Employees

• Business partners

A brand’s power comes not just from the loyalty that it creates in its customers, but also from the loyalty that it creates in its employees and its investors.

Brand Building and Marketing Are Investments with a Tangible Return

I am tired of hearing some businesspeople say that there is no way to correlate business results with marketing expenditures, implying that marketing is an expense with no corresponding return. Others are slightly more charitable and say that there is no way to measure direct results. This is wrong—at least for direct response marketing, including direct response marketing via the Internet. (Many direct marketing websites even offer free direct marketing ROI calculators.) For other types of marketing, this conclusion is partially wrong.

There are a few important components to measuring the results of marketing programs. They include 1) being clear about the program’s objectives up front, 2) being sure that there are ways to measure results against the objectives, 3) measuring those results, and 4) evaluating the program’s results against the objectives. This is a closed-loop system.

It is also important to keep in mind that there are marketing programs with long-term results, such as brand building, and there are marketing programs with short-term results, such as direct response marketing and sales promotion. You must be clear about which ones each marketing investment is intended to achieve (see Figure 18–3).

Figure 18–3. Long-term vs. short-term marketing investments.

Long-Term Investment |

Short-Term Investment |

|

Type of Marketing Investment |

Brand building |

Direct response marketing, sales promotion, and other shorter-term marketing expenditures |

Primary Result |

Creation of leverageable asset |

Short-term increase in sales |

Indirect Impact on Business |

- Decreased price sensitivity - Increased customer loyalty - Increased revenues - Increased share of market - Increased ability to hire and retain quality employees - Increased stock price - Increased company value - Increased ability to grow into new product and service categories - Increased ability to mobilize the organization around a vision |

NA |

Measurement |

Financial: asset value Nonfinancial: awareness, relevant differentiation, preference, loyalty |

Program ROI |

Measuring Marketing ROI

There are many useful models for estimating the impact of various revenue drivers on total revenues. One of the more widely used models is based on the following calculation:

The total customer base (number of people)

× (multiplied times) the average number of purchase transactions per person (per time period)

× (multiplied times) the average unit sales per transaction

× (multiplied times) the average price per unit

× (multiplied times) the percent of those transactions received by your brand

= (equals) your sales (per time period)

You can design your marketing programs to affect any combination of these factors, and you can measure the level of investment required to get the results through each of these levers:

• You can introduce your products to new audiences.

• You can encourage customers to upgrade their products or services or to purchases additional products and services.

• You can entice them to make more frequent purchases.

• You can increase the amount that they pay for the products and services.

• Your can encourage them to rely on your brand for a greater proportion of their purchases.

Given the right data, it becomes trivial to estimate the return to your company from increasing your market share by one share point, gaining one more customer, or retaining a current customer’s business for another year.

Take another example: lead generation. If you code ads and direct mail pieces, you will be able to determine which marketing programs resulted in leads, which of those leads were qualified, which of those qualified leads were translated into sales by your sales force, and how much revenue each of those successful leads returned. You can relate this result to the marketing investment required to generate those leads. Now you have calculated return on marketing investment.

Many marketing tactics achieve numerous objectives. For instance, banner ads have been shown to increase brand awareness and reinforce a brand’s positioning while also generating sales leads or transactions (depending on what is on the other side of the click-through). Trade shows also achieve multiple ends. Through our postshow research, Element K has found that shows increase brand awareness and preference and the prospect’s propensity to purchase our products. They also increase current customer attitudinal loyalty. They generate qualified sales leads as well. Be careful to evaluate marketing tactics that achieve multiple ends against all of those ends—not just one.

On a macro basis, one can measure the effectiveness of marketing expenditures by comparing increases in total marketing expenditures to increases in sales for a specified period of time (e.g., quarter-over-quarter, year-over-year). Two cautions with this approach, however. First, a complex combination of variables affects sales. Not all the credit (positive or negative) can be attributed to marketing actions. The general economy, sales tactics, and other executive-level decisions can also impact sales in significant ways. Second, remember that some of your marketing programs, including most brand building programs, are designed to affect a longer-term cumulative result not measurable in the short term.

Importance of Investing in the Brand Asset

A number of studies have shown that the percentage of a company’s value that is unaccounted for by tangible assets has increased significantly. From 50 percent to 90 percent of a company’s total value is now attributable to factors other than tangible assets. In a 2013 study, the intellectual capital equity firm Ocean Tomo discovered that nonfinancial assets account for as much as 80 percent of institutional investors’ valuation of a company. In 2000, Cap Gemini Ernst & Young joined with Forbes Magazine and the Wharton Research Program to develop the Value Creation Index, a method for determining the real value of intangible and nonfinancial assets. In “Measuring the Future: The Value Creation Index,” Cap Gemini reported that, after rigorous research, it discovered that 50 percent of a traditional company’s value and 90 percent of an e-commerce company’s value result from nine factors. The following value drivers seem to be common across most industries:1

• Innovation/R&D

• Quality of management

• Employee quality/satisfaction

• Brand investment

• Product/service quality

Neel Foster, a former board member at the Financial Accounting Standards Board, once said:

As we move into more of an information age and service-based economy, the importance of soft assets is becoming more relevant to valuing some companies than brick and mortar. A lot of companies don’t even have brick and mortar.2

An increasing number of methods have emerged to measure nonfinancial business drivers, from economic value added and the balanced scorecard to value-based management and the Value Creation Index. Wharton accounting professors conducted a study across 317 companies and discovered that 36 percent of the companies sampled used nonfinancial measures to determine executive incentive compensation.3

Building brand awareness, differentiation, and emotional connection together with the appropriate pricing and distribution strategies results in brand preference, purchase, repeat purchase, and, eventually, loyalty. Also, an increasing body of evidence links brand building activities with a wide range of long-term benefits, from decreased price sensitivity and increased customer loyalty to increased stock price and shareholder value.

Sometimes, the results of brand building programs are obvious, especially for new brands. When I arrived at Element K, it was a newly created brand. People in the e-learning industry had not heard of Element K. Our sales force found it difficult to gain the attention of potential buyers: We were not on industry analysts’ “radars,” we did not receive coverage in trade magazine articles, people passed by our trade show booth, and we got few calls from conference companies. After a year of focused and relentless brand building efforts, prospects started coming to us (we are on their “short lists”). Soon we were in all of the industry analysts’ reports, our president writes a column for one of the major trade publications, we sponsor a major user conference in parallel with one of the most important industry trade shows, we receive a continuous stream of invitations to participate in conferences and other industry events, companies approach us about business partnerships, our employees are sought after as industry experts, and our competitors talk about us. In this case, the results of our brand building efforts were obvious and didn’t require the validation of formal brand equity measures or the corresponding revenue increases (both of which we also have).

You can measure and manage the nonfinancial impact of your brand through a brand equity measurement system (covered earlier in this chapter). You can also measure the financial value of your brand as an asset.

Brand valuation has been made possible by a number of financial approaches—activity-based costing (ABC), discounted cash flow (DCF), and economic value added (EVA)—and by a myriad of more recent customer purchase tracking techniques.4 Interbrand (www.interbrand.com) has a depth of experience in brand valuation. Also, Don E. Schultz, Ph.D., professor of integrated marketing communications at Northwestern University and president of Agora, Inc., has studied and applied the concepts of brand valuation and return on marketing investment in depth. Both would be good resources for people with a further interest on this topic.

Brand Building and Marketing as Investments: A Summary

1. Brand building is an investment that results in a significant leverageable asset.

2. Other shorter-term marketing actions exist for the sole purpose of increasing sales.

3. You can measure the asset value of brands.

4. You can also measure the nonfinancial aspects of brands that drive positive financial consequences in the long term—awareness, relevant differentiation, and loyalty, for instance.

5. You can and should measure ROI for other shorter-term marketing programs.

6. Brands are a primary source of value creation for organizations.

7. Although some businesspeople (typically finance and operations types) may view marketing as an expense without significant corresponding benefits, this is untrue. Marketing is one of the most important investments a company can make.

Implication: Don’t look first to marketing (and employee training, for that matter) when expenses need to be trimmed to achieve short-term goals. This decision will only hamper value creation and revenue growth in the long term.

Marketing is a fundamental driver of organizational success. Together, brand building, marketing. and sales strategies and tactics create, build, and sustain a company’s revenues. To ensure positive results, you must understand and track how each marketing program impacts sales in the short term and the long term. In many instances, you will be able to track and measure the specific short-term impact of specific programs. In others, especially for longer-term brand building programs, you will have to track and measure indirect business drivers (e.g., brand awareness, attitudinal loyalty) and validate how each of these affects revenue gains in the long run. Formal marketing (and brand) plans and metrics will help you achieve this end. And don’t forget—a brand is an asset, and one of the most important assets in creating long-term value for organizations. Build the brand, sustain it, and leverage it.

Use the checklist in Figure 18–4 to assess the efficacy of your brand management practices in the area covered by this chapter. The more questions to which you can answer “yes,” the better you are doing. The checklist also provides a brief summary of the material covered in the chapter.

Figure 18–4. Checklist: Brand equity measurement.