Our fourth skill is your ability to adopt a flexible style of influence during conversation. We’ll look at the different ways you influence someone during a conversation and highlight a range of ways to do that. We’ll build on previous principles, for example directive and less directive styles, and show how it’s not a choice between the two: sometimes you can move between or combine styles. As you’d expect, I’ll offer hints, tips and guidance to encourage you to get the most from the ideas.

What do we mean by ‘flexible style of influence’?

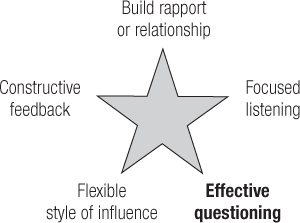

As a quick reminder, there are two basic ‘ends’ to our spectrum of influence as Figure 8.1 illustrates.

Figure 8.1 Spectrum of influence

Why is flexibility important to develop?

You’ll remember that a coaching conversation influences the thoughts, behaviour and learning of another person. We do that by effective listening, questioning, offering feedback, etc. However, it’s important to notice that a coaching conversation isn’t just you asking lots of questions of someone else.

Consider that idea for a moment: imagine all you’re allowed to do during a conversation is ask questions, nothing else. For you as questioner you might feel constrained or even frustrated. You’ll want to say things, make an observation perhaps, but feel like you’re not allowed to do that. As a manager, you might also hear things that don’t make sense, or that you know you can’t allow to happen. For the person being coached, a list of questions with no ‘input’ from you might feel odd, unnatural and potentially puts them under pressure. The conversation needs to feel natural for you and natural for the person you’re with. So, to stay effective and retain your sense of comfort during conversations, you need to use other behaviours. This helps you move from being more directive when that feels right, then return to a less directive and encouraging style. Coaching someone shouldn’t mean you have an apparent personality change, or lose your natural, easy-going style.

Two ends of a scale, with behaviours in between . . .

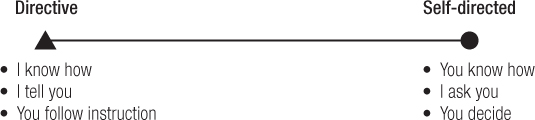

Some language is clearly directive and attempts to influence directly, for example ‘I want you to do this’. Other language encourages someone to decide for themselves, for example ‘What do you want to do?’ Between these two extremes are behaviours that exert different strengths of influence. For example, if I make an observation on or about something you have said, this will have a more ‘neutral’ impact on you than if I gave you direct advice (see Figure 8.2).

Figure 8.2 Scale of influence

Let’s look at the different behaviours on the scale (-Figure 8.2) and reflect on how you might use them. We’ll start with the less directive behaviours and move towards the more directive end of the scale (from right to left of the figure).

![]()

How much flexibility do you already have?

Use the following questions to increase your self-awareness in this area. Another way to do this would be to have someone observe how you typically influence others, for example in a meeting, and then ask them to answer the questions on your behalf.

Q: During a typical conversation, what seems more important: giving your opinion or making an effort to understand someone else’s?

Q: How often do you simply summarise what someone’s said, without adding your own opinion or ideas immediately afterwards?

Q: How often do you make observations about what someone is saying, simply to draw their attention to something that might help them, i.e. without following up with your own view?

Finally, spend a little time reflecting on how much you feel compelled to influence at all. For example, are you comfortable to simply facilitate a conversation with no input on the content of that conversation?

Behaviour 1: Say nothing

The behaviour of ‘saying nothing’ is a little strange to imagine as an influencing style, yet silence as a response to what someone has just said can sometimes be perfect. Silence enables someone to pause, reflect on what they’ve just said, or perhaps go deeper into what they are saying. It suggests calmness from you and allows the other person to relax and speak from the sense of ease that you have created. It also helps you to really listen to the other person, perhaps observing their body language or energy. Like all the behaviours described here, overusing silence can have the reverse effect and cause the other person to feel tense because you’re not responding to them verbally. When silence becomes too uncomfortable for the person you’re coaching, you’ll notice by their non-verbal signals, for example changes in their posture, tone or facial expressions. Some signals are clear indications that you need to speak, for example if they stop speaking and look directly back at you with an expectant expression. Other signals are subtler, for example over time you may notice signs that they appear frustrated or tense.

Behaviour 2: Ask an open – neutrally worded – question

For a question to have the least directive style of influence, it should be both open and worded as neutrally as possible. For example, ‘Do you think you should plan the meeting in advance with Bill?’ is closed as it can be answered simply with a ‘yes’ or ‘no’. The question also attempts to be directive: you’re suggesting they should plan the meeting. A more neutral question might be ‘How will you prepare for the meeting?’ Although this question is still mildly directive, as you’re suggesting preparation is necessary, it may be both appropriate and helpful (to help someone think the preparation through). Alternatively, you might be guiding the person too specifically/strongly, perhaps because they need to talk about some other aspect of the meeting first. As always, you are the best judge of your situations and can decide when you need to have a more direct influence on the conversation. A third, very neutral question in that situation would be ‘What thoughts are you having about the meeting now?’ This may be too vague but, on the other hand, could be just perfect to help them think. Again, your internal sense of what’s best to do is one that you need to develop.

![]()

Your body will help you if you let it!

After 20 years of coaching people, I’ve learnt that the following is ‘strange but true’.

Your body can often help as an indicator of how a conversation is going, or even act as a guide to suggest what you should do next. Learn to ‘tune in’ to your body during coaching conversations, particularly your head, stomach and torso, so that you can check occasionally to see how it corresponds to what’s happening. For example:

Q: If the conversation is ‘in flow’, i.e. going well, how does your body feel?

Q: When you know something’s not right, how does your body feel?

Q: When you need to make a decision, for example to stay quiet or to speak, how does your body indicate that?

As you gain an increasing awareness of – or connection to – your body, you’ll learn to trust and be guided by it. For example, maybe I’ve been talking to someone about a topic for a while and get a growing sense that the conversation feels ‘hollow’, or as if the conversation isn’t going anywhere. When I check my body, I have a feeling that resonates, or is noticeable in some way. Perhaps there’s lightness in my stomach or shoulders, or maybe the top of my head feels odd. Or maybe I’ll consider asking a certain question but my stomach feels heavy when I think about it, so I’ll stay quiet. These are just a few of my signals – how your body communicates with you will be distinct to you. The signals from your body are a way to access your natural intuition and can be a real enhancement to your coaching ability. Your awareness may take a little time to grow until you can fully trust your senses, but it will make a positive difference to your efficiency and results as a coach.

Behaviour 3: Summarise what you’ve been hearing

When you summarise what someone has said it’s often helpful for the person you are listening to, and also for you.

For you, giving a summary helps you to:

- Demonstrate that you’ve understood the key points of what someone has said, and so confirm mutual understanding.

- Draw the other person’s attention to what you are suggesting are the key facts of the situation, and to filter out any less relevant facts simply by not mentioning them.

- Stay involved in the conversation, for example as perhaps someone has been talking for a long time without interruption.

For the other person, offering them a summary helps to:

- Give them a rest from talking and space to reflect on what they’ve been saying.

- Enable them to stand back and listen to their situation from your perspective and so gain a more objective view of key facts or events.

- Become more conscious and aware of the conversation, perhaps as they have digressed in some way and have got lost talking about something less important or less relevant.

The benefit of a simple summary might surprise you; when someone hears what they’ve just said, they often have ideas or insight they might not have found otherwise.

Less is more

Giving summaries can be so delightfully beneficial that we can overuse it as a tool. In conversation, too many summaries slow progress and potentially frustrate the person who is trying to talk. The following principles indicate when a summary might be appropriate:

- When you haven’t spoken for a long time and you’re experiencing a sense of becoming disconnected with the person talking, for example they’ve lost eye contact with you and seem to be talking almost to themselves.

- When you feel that the conversation is rambling or going round in circles, i.e. the same or similar facts seem to be being repeated.

- When you’re unclear as to what you’re hearing and want to check that you understand what the other person is saying or feeling.

- When you think that the other person is becoming fatigued or confused and might appreciate a rest from talking, or benefit from some time to reflect.

- When you particularly want to draw the other person’s attention to something they’ve said, for example a word, phrase or sentiment.

Behaviour 4: Make an observation

An observation is when you notice something that the other person has said and choose to draw their attention to it. It has a more directive influence than a summary, because you have a clear reason for drawing their attention to it. Perhaps they have contradicted themselves in an interesting way, or maybe they’ve been using a certain phrase or negative language repeatedly and appear unaware of doing that. In giving an observation, it’s important that you appreciate how subjective or objective your observations are. When your observations are more subjective, i.e. they contain more of your interpretation or opinion, they become more directive, as the following table illustrates.

There are no right or wrong examples here; any of the above may be valid choices, depending on your situation and what seems helpful for the other person.

Behaviour 5: Give an opinion

When you give your opinion you draw upon your own thoughts, knowledge and experience to offer your view of someone else’s situation. This is more directive than a summary or an observation, as you have judged the situation and are trying to influence someone else’s view or decisions. Be aware that some opinions are more forceful than others, and the type of opinion you offer relies on:

- your sound judgement of a situation

- the level of rapport/trust you have with the other person

- someone’s appetite or potential to hear your opinion and be open to it.

The table below illustrates this.

Develop flexibility by relaxing your own habits

I’ve described a range of influencing behaviours in order to paint a fuller picture of that range. However, you already use many of these behaviours, often without noticing. I’d guess that you give opinions, advice and instruction naturally but rarely summarise or offer simple observations in order to help someone else think. To develop your true flexibility, try the following.

- First, increase your self-awareness by noticing how you typically influence during conversations, or maybe ask a colleague to observe you, for example in meetings.

- Next, decide on a period of time during which you will avoid using your typical behaviours, such as giving opinion or advice, to force yourself to use other responses, such as summarising or making observations. It’s often helpful to share with a trusted colleague what you intend to do (this emphasises your commitment).

- Finally, notice the difference this makes, perhaps asking a colleague for feedback, for example ‘Did this work? What difference does it make?’

When you’ve given this a try, decide for yourself which behaviours will most benefit you. Remember, the aim of doing this is to influence people in a way that helps people think and act for themselves. So when you’re reviewing ‘Does this work?’ you need to notice if you did that – or not!

Behaviour 6: Give advice

When you give advice, you tell the other person what you think they should do, and accept that they might not actually do it. This is much the same as you might do with a friend, for example ‘If I were you . . . ’ or ‘What I would do is . . . ’ Advice is different from opinion because there is a more open intention to affect the behaviour of another person. To be an effective coach, you should give advice only sparingly and with caution. As you already know, coaching leans away from telling people what they should or could do in favour of helping them to think through a situation and decide for themselves. In the early days of learning to coach, I encourage you to avoid giving advice; instead develop your ability to be less directive. However, it’s also true that there are times when your advice is relevant, useful and supportive and so is exactly what’s needed in the situation. The table below will help you reflect on the different ‘strengths’ of advice, from allowing someone to retain self-direction to giving almost a directive instruction.

| Your advice | Level of ‘directiveness’ |

|---|---|

| I wonder if you might benefit from a conversation with the HR department. | This is subtly worded and almost ‘offers’ the advice as something that can easily be rejected. |

| I think you should go and speak to the HR department. | This is simple, clear and to the point; it is also owned, i.e. ‘I think’. |

| It’s really important that you speak to the HR department and get some expert input here. | This is assertive and pointed, and so is ‘directive’ or suggesting of action. |

Please remember that if you are a person’s manager or boss any advice from you may feel like an instruction to them. Your subordinates might expect, or feel that they need, instructions or solutions from you. If you can see this is the case with some people you work with, please put advice in the same category as instructions, because they create the same directive effect on those people. Another option might be to signal that the advice isn’t instruction, for example ‘This is just gentle advice – you must decide what’s best for you here.’

How to deal with a dumb idea

Encouraging someone to be self-directed doesn’t mean that you need to let them do whatever they want, regardless of the potential consequence. As you develop your flexible style of influence, you can ‘pull and push’ on the directive lever of influence as the situation warrants. The following dialogue illustrates this.

| Manager | So what do we need to do to win this guy’s business? |

| David | I’d like to offer them a bigger discount. I know we’d get the business if we do that. |

| Manager | Well, yes, that might increase our chances, but we’re pretty much down as low as we can go on price. So that’s not an option, I’m afraid. |

| David | Okay, I didn’t realise that. What do you think we should do then? |

| Manager | I think I’m interested to understand what other ideas you can come up with. After all, you have a good relationship with him. Okay, so apart from price, what else is important to him? |

Here our manager rejects an unfeasible idea by explaining why it’s not possible. The manager then avoids a temptation to offer a solution (and so direct David’s actions), as they return to challenge David to keep thinking/working, i.e. ‘what else is important to him?’

Behaviour 7: Give an instruction

As you’d expect, when you instruct someone to do something, you aim to influence them by directive means. Interestingly, some instructions are stronger than others. Some instructions prescribe specific, detailed actions, while other ‘instructions’ tell people how best to work things out for themselves. So you can use a directive instruction to help someone to be self-directed! The table below explains this apparent contradiction.

| The instruction | Directive or encourages self-direction? |

|---|---|

| Go and speak to Jon and ask him to reschedule the meeting. | Clearly a directive instruction (or request), it suggests that you know what should happen and that you are telling someone to do that. |

| Go and speak to Jon and figure out a solution that you both agree on, and then let me know what you want to do. | Although this is a directive instruction, it still allows the other person a level of empowerment – to decide for themselves what they are going to do. |

| Okay, take the rest of the day to figure out a solution to this. Get back to me by the end of the day and let me know what you’re proposing to do. | This is clearly directive and yet expects the other person to provide a solution. It may put the person under some pressure, which may or may not work well. |

Please remember that the above statements can have different effects depending on your manner and tone of voice. For example, a harsh, punchy, snappy tone has a far different impact from a warmer, relaxed one. Try saying the above statements out loud using different styles of speech to explore this idea for yourself.

It’s both unnatural and impractical for your coaching conversations to be merely a list of questions from you, where you allow other people to decide what to do and how to do it. As a manager, you need to be able to balance empowering people with a need to stay practical, within the rules, etc. This means that you need to develop the flexibility to use different methods of influence, both with different people and during the conversations themselves. Being able to use intermediate behaviours, such as giving summaries, making observations and offering opinions, will help you do this.