6. Goals, Strategies, and Tactics: Preparing and Planning

On August 6, 2010, late on a Friday afternoon, investors in HP (formerly known as Hewlett-Packard) got a surprise. The company announced that Chief Executive Officer Mark Hurd, who was widely credited with turning around the troubled company, was resigning.1

That was surprising enough. But the reasons given were both murky and baffling. And it began a year of communication, strategy, and execution missteps that caused confidence and trust in the leadership of the company and its board to plummet.

In its announcement the company said that the general counsel, overseen by the board, had conducted an investigation of an allegation of sexual harassment against Mr. Hurd. Readers of the announcement might have concluded that the next sentence would confirm the allegation. But it didn’t. It said that the investigation had concluded that he had not violated the company’s sexual harassment policy. So why was he leaving? It wasn’t clear. The announcement said that the investigation had found “violations of HP’s Standards of Business Conduct.”2

The announcement did not specify anything about either the sexual harassment allegations that prompted the investigation, or the nature of the violations of the code of conduct that apparently led to the resignation. It did quote Mr. Hurd saying:

As the investigation progressed, I realized there were instances in which I did not live up to the standards and principles of trust, respect, and integrity that I have espoused at HP and which have guided me throughout my career. After a number of discussions with members of the board, I will move aside and the board will search for new leadership. This is a painful decision for me to make after five years at HP, but I believe it would be difficult for me to continue as an effective leader at HP and I believe this is the only decision the board and I could make at this time. I want to stress that this in no way reflects on the operating performance or financial integrity of HP.3

Investors were confused and alarmed. Shaw Wu, an analyst at Kaufman Brothers, told investors, as quoted by the Associated Press, “We are frankly surprised and disappointed as Hurd was a strong leader and helped transform HP into a leading player.”4

The public announcement gave few details about what had happened and why. But soon after that announcement, an internal e-mail from interim CEO Cathie Lesjak gave a little more information to employees. The e-mail promptly leaked and was part of the initial round of press coverage. Ms. Lesjak told employees that Mr. Hurd had

failed to disclose a close personal relationship he had with [a] contractor that constituted a conflict of interest, failed to maintain accurate expense reports, and misused company assets. Each of these constituted a violation of HP’s Standards of Business Conduct, and together they demonstrated a profound lack of judgment that significantly undermined Mark’s credibility and his ability to effectively lead HP.5

The e-mail didn’t give more specifics about the “misuse of company assets.” But failing to disclose a close personal relationship with a contractor and filing inaccurate expense reports seemed relatively minor compared to the dismissal. The remedy seemed out of line with the offense.

The company’s general counsel briefed reporters by conference call that afternoon and added a bit more detail. He said that Mr. Hurd had a “close, personal relationship” with a female contractor for two years that he had not disclosed to the board. He said that Mr. Hurd’s conduct “exhibited a profound lack of judgment” and that HP’s board had insisted that he resign.6 The board’s insistence that he resign for failing to disclose a personal relationship with a female contractor also sounded out of proportion. Did he have a relationship before that person became a contractor? Did he develop it while she was a contractor? What kind of relationship, and why would that require disclosure to the board? And saying that the board insisted that Mr. Hurd resign meant that he was essentially fired. He wasn’t leaving by his own choice, but by theirs.

So the three different statements provided three different levels of detail:

1. The announcement mentioned an investigation of an allegation of sexual harassment, noted that Mr. Hurd had not violated the company’s sexual harassment policy, but found that he had violated the code of conduct. It didn’t give details. It quoted Mr. Hurd as saying that he had failed to live up to a standard of trust and integrity. He also said that the issues were unrelated to the operating performance or financial integrity of the company. That suggested some personal failing.

2. The internal e-mail gave a bit more detail: an undisclosed relationship with a contractor, inaccurate expense reports, and misuse of company assets.

3. The press conference call went a bit further: the undisclosed relationship was with a female contractor, and the board had lost confidence in him because of a lapse in judgment, and forced him to resign. Could it be that he had harassed the woman but because she wasn’t an employee he technically hadn’t violated the company policy?

The three public statements were consistent in not giving any details that would allow stakeholders to understand what had actually happened, how big it was, and what it meant.

On Monday, August 9, the first business day after the announcement, CNBC reported that Mr. Hurd would collect between $34 million and $40 million in severance payments. Other news reports calculated it to be closer to $50 million. Kevin Murphy of the University of Southern California Marshall School of Business told CNBC that he was puzzled by the validity of a severance package if Mr. Hurd was essentially being terminated for an ethical breach. Frank Glassner of the compensation consulting firm Veritas Frank Glassner went further, calling Mr. Hurd’s removal and the manner in which it was announced “a huge lapse in thought and judgment by the board.”7 Over the weekend commentator Henry Blodget had asked, “So, on behalf of HP shareholders, we have a question for HP: Why is Mark Hurd getting a $50 million severance payout if he filed bogus expense reports? And why was he allowed to ‘resign’? Why wasn’t he fired for cause?”8

These were all reasonable and appropriate concerns and questions, and easy to anticipate with a little planning. But they were left open for commentators, critics, and competitors to raise. The stated reasons, frankly, didn’t make much sense.

Larry Ellison, Chief Executive of Oracle Corporation, told the New York Times, “The HP Board just made the worst personnel decision since the idiots on the Apple board fired Steve Jobs many years ago. That decision nearly destroyed Apple and would have if Steve hadn’t come back and saved them.”9 Oracle was both a competitor and a partner of HP, depending on the business line.

Business partners were also surprised. “I am shocked. It’s always a shock whenever someone of that stature departs suddenly for any reason,” said Mont Phelps, CEO of HP partner NWN. Chris Case, CEO of Sequel Data Systems, another HP partner, said, “It’s disappointing news because Hurd was always a huge advocate for partners.” Future Tech Enterprises CEO Bob Venero said, “Mark had a clear vision of where he was going,” and wondered, “Are they going to stay on that line or is whoever they’re going to bring in going to change that dynamic? From a partner perspective, that’s a scary thought.”10

HP stock fell more than 9 percent after the initial announcement, losing more than $8 billion in market value. The stock would continue to fall as events played out in somewhat predictable ways and as more and more stakeholders began to question the thoughtfulness, judgment, and ultimately the effectiveness of the board. And as the board gave stakeholders more and more reasons to.

One week after the announcement, the board was sued by investors who alleged “gross mismanagement and waste of corporate assets” related to the severance package and other missteps.11

Planning Isn’t Looking at a Calendar; It’s Looking at a Chessboard

Sir John Harvey-Jones, the British industrialist and later host of the BBC Troubleshooters television program, famously said that “the nicest thing about not planning is that failure comes as a complete surprise.”

That seemed to be the case at HP. The initial announcement was so vague, and with so many inconsistencies and gaps, that stakeholders predictably needed far more information to be able to make a judgment about the company: investors about whether to continue to have confidence in the company as an investment; employees to get clarity about what was expected of them; business partners about whether to continue to do business with the company, and on what terms.

HP’s board left stakeholders wanting and needing to know much more than what the company, in its three initial communications, told them.

Projecting thoughts forward is the key to planning. And as we project our thoughts forward, we need also to project our stakeholders’ thoughts and likely reaction forward. As we have noted in earlier chapters, all communication is a process of continuous mutual adaptation, of give and take, of move and countermove. And there’s a powerful competitive advantage in being the first mover, which HP was in this case. But for the first mover advantage to work, it needs to be implemented well. Like any other powerful tool, used poorly it can cause significant self-inflicted harm, as it did for HP.

And part of getting the first mover advantage right is to anticipate stakeholders’ reactions and to adapt the initial communication to neutralize those concerns before they are raised. Here’s the rule of thumb for communicating bad news:

• Tell it all.

• Tell it fast.

• Tell ’em what you’re doing about it.

• Tell ’em when it’s over.

• Get back to work.

“Tell it all” means saying all that is necessary to establish stakeholder understanding, buy-in, acceptance, or at least neutrality. “Tell it fast” means getting all the news out at once, in a single news cycle, and preventing the dripping out of new details over time, each of which creates a new news cycle and causes stakeholders to continue to wonder about the leadership skills of those who are communicating.

Indeed, veteran journalist and chronicler of corporate malfeasance James B. Stewart wrote in SmartMoney magazine:

When will the Hewlett-Packard board learn the most fundamental lesson of corporate governance and public relations? That lesson is simple: Disclose all relevant facts, get ahead of the media, and don’t turn a one-day story into a media frenzy.

In U.S. public companies, the directors are supposed to serve the owners the shareholders [sic] and not management or themselves. Shareholders deserve, and are entitled by law, to material information about the company. Boards should err on the side of transparency. Concealing facts only breeds suspicion, not to mention intense media coverage. That someone might be embarrassed by full disclosure is irrelevant and shouldn’t factor in any disclosure decisions.12

There are other reasons besides public relations to anticipate stakeholder reactions. The very process of considering likely reactions to proposed communications can reveal failures of planning in the actual business decision making. As Admiral Mullen noted in the first chapter, too often what are labeled failures of communication are really failures of strategy and execution. Communication planning can serve as the canary in the coal mine—as a leading indicator that something is amiss in the business planning process. The need to explain something often calls attention to some inconsistency in decision makers’ thought process.

Indeed, commentators told the New York Times that the rationale for the termination didn’t seem to add up. Shane Greenstein, a business professor at Northwestern University’s Kellogg School of Management, said, “There is a missing piece here because it doesn’t make sense.”13 Oracle’s Larry Ellison went further, suggesting that the board was insincere in giving its reasons for Mr. Hurd’s departure:

What the expense fraud claims do reveal is an H.P. board desperately grasping at straws in trying to publicly explain the unexplainable; how a false sexual harassment claim and some petty expense report errors led to the loss of one of Silicon Valley’s best and most respected leaders.14

In SmartMoney James B. Stewart said,

When I contacted H-P, a spokesman declined to answer any of my questions and said the company had nothing to add to what it said Friday when it announced Hurd’s resignation. He would not say whether, as part of Hurd’s agreement to resign, H-P promised not to disclose...any details of what its own investigation uncovered. In my view, that is not good enough. H-P still has plenty of questions to answer, including its justification for paying Hurd an exit package worth more than $35 million even while forcing him to resign. Until it does, it is hard to have any confidence in the judgment of H-P’s board and as an investor, I’d avoid the stock.15

Planning isn’t just determining a sequence of actions and writing a statement based on what you want to say or are minimally required to say. It’s about a chessboard, not a calendar. It’s about thinking several moves ahead: If we do X, what will they do, and what will we then need to do next? If we do Y, what will they do, and so on. So planning requires understanding the absolutely predictable and appropriate expectations of stakeholders, anticipating and then meeting those expectations. As Mr. Stewart noted in SmartMoney, failing to meet stakeholder expectations can cause them to lose trust and confidence.

The HP board failed to shape the communication agenda. It failed to recognize a paradox of crisis communication: that if you want others to not talk about you, sometimes you need to say more than you may initially want to. Because all effective communication is goal-oriented, intended to change something, an effective leader or leadership team focuses on what it wants stakeholders to know, think, feel, and do, and the ways to get those stakeholders to change so that they will know, think, feel, and do so.

Shaping the communication agenda requires considering more than what we may be minimally required to say, but rather identifying what we optimally should say in order to maintain trust, confidence, and loyalty.

In HP’s case, right up until the very moment of its announcement, stakeholders held Mr. Hurd in the highest regard, thinking of him as the white knight who had rescued HP from itself as it was spiraling out of control. He was the hero. And for him to leave so suddenly, something quite egregious must have happened; still, if he had to leave that way, why did he receive severance?

The circumstances all called to mind the very kinds of problems, embedded deep in the governance of HP, that Mr. Hurd had supposedly fixed.

Hurd to the Rescue

Before Mr. Hurd’s arrival five years earlier, HP had developed a reputation as a company that couldn’t shoot straight. It had gone through serial blunders, of strategy, of execution, and of ethics.

Early in the decade, then-newly-arrived CEO Carly Fiorina pushed through a highly controversial acquisition of Compaq computer, against the strong objections of many investors, including the heirs to the company’s founders. The merger proved to be a disaster, and in early 2005 Ms. Fiorina was fired. She was succeeded as board chair by Patricia Dunn, former CEO of Barclays Global Investors, and as CEO by Mark Hurd, former CEO of NCR Corp.

Ms. Dunn had a rocky tenure as board chair. Alarmed that the media was publishing information about private board discussions, in early 2006 Ms. Dunn authorized external security consultants to spy on board members and journalists. Among the techniques the investigators used was “pretexting,” pretending to be board members and asking phone companies to send them copies of recent bills. That way they could see whether the directors had contacted the news media. Pretexting is a crime, a form of identity theft. The investigators discovered the leaker, but when Ms. Dunn informed the board of the manner in which the leaker was identified, there was a boardroom rebellion.

Tom Perkins, a member of the board and chair of its nominating and governance committee, resigned in protest. Under U.S. law, when a director resigns from a board because of a disagreement about the company’s operations, policies, or practices, the company is required to so disclose. But the company’s filing with the Securities and Exchange Commission did not mention the reasons, and its press release about the departure merely thanked him for his service.

When the story about Ms. Dunn’s investigation, the boardroom rebellion, and Mr. Perkins’ reasons for his resignation became public, there was a loud public outcry and Ms. Dunn was forced to resign. She was indicted by the California Attorney General, but the charges were later dropped.

Mr. Hurd, who was not implicated in the spy scandal, was called to testify in front of a congressional committee. He apologized to the board members, employees, and journalists whose privacy had been violated; confirmed a commitment to integrity; and outlined steps the company was taking to get to the bottom of what had happened and to put structures in place to prevent a recurrence.16

The scandal died down, and Mr. Hurd got on with the job of running the company. He was wildly successful, at least in investors’ eyes. He reorganized the company into three divisions, making each division head accountable for sales targets. He cut expenses significantly, including through large staff reductions. During his five years in office, revenues grew by a third, net income tripled, and the stock more than doubled.

So after five years at the helm, it was quite startling for investors to hear that Mr. Hurd was leaving under an ethical cloud.

Hurd on the Street

What happened? According to published reports, HP had a marketing program whereby Mr. Hurd would attend big industry conferences. At those conferences the company would invite executives from some of HP’s largest customers to relationship-building events it called “Executive Summits.” HP contracted with Jodie Fisher to serve as a hostess at the summits, to chat up customer executives to make them feel at home, and at the right moment walk them over to Mr. Hurd to talk business.

Time magazine described Ms. Fisher as “a former actress and reality-television personality.”17 She and Mr. Hurd became friendly as they got to know each other, and they would often dine together while on the road. It was those dinners, apparently, that were characterized inaccurately on Mr. Hurd’s expense reports. The total amount in question was under $20,000. Both Ms. Fisher and Mr. Hurd have said publicly that they never had an affair or any sexual relationship. In the ordinary course of business, the program was discontinued and Ms. Fisher’s contract was terminated.

On June 29, 2010, Mr. Hurd received a letter from celebrity lawyer Gloria Allred alleging that Mr. Hurd had made improper advances to Ms. Fisher during her tenure as a contractor for the company. The letter was unsealed by the courts in late 2011 but was not available publicly as the events unfolded in 2010. It outlined in dramatic detail vivid accounts of Mr. Hurd’s conversations with Ms. Fisher. Ms. Allred said she was “prepared to move forward and seek all available legal remedies” on Ms. Fisher’s behalf.18

Mr. Hurd forwarded the letter to HP’s general counsel, who notified the board. The company retained the law firm Covington & Burling to conduct an internal investigation. That investigation turned up inconsistencies in Mr. Hurd’s account of his relationship with Ms. Fisher, and inaccuracies in his expense reports.

According to an account of board deliberations by Fortune magazine,

Whether or not the two had been physically intimate—representatives of both Hurd and Fisher have publicly asserted that the two did not have a sexual relationship—several directors felt that Hurd’s story had changed from their initial informal inquiries to his answers to the investigators. Hurd’s initial denials of an inappropriate relationship with Fisher had been so vehement that, when it turned out there was evidence of a close relationship—including the fact that Hurd and Fisher dined together out of town on two occasions when Fisher was not working at an HP event—some members of the board simply lost their trust in Hurd.19

At that point the question shifted from whether Mr. Hurd should go to when and how. He suggested a minimal disclosure about the lawsuit, and his resignation several months later, which could be characterized as a retirement. The board rejected that proposal.

The board’s lawyers had scheduled a mediation session with Ms. Fisher for the first week in August in which they hoped to get to the bottom of what had happened. But late in the evening of August 4, Mr. Hurd settled Ms. Fisher’s lawsuit. The terms were confidential. The board had not been aware that Mr. Hurd was negotiating a settlement, and was surprised to learn about it the morning of August 5. By settling the suit, Mr. Hurd essentially prevented the board’s lawyers from hearing from Ms. Fisher directly. So the board would not be able to learn Ms. Fisher’s side of the story. It was the last straw. The entire board lost trust in Mr. Hurd, and he had to go. HP announced his resignation the next day.20

Measure Twice, Cut Once

Then on September 6, just one month after leaving HP, Mr. Hurd joined Oracle as co-president, essentially becoming CEO Larry Ellison’s right-hand man.

HP investors were outraged. How could the former HP CEO get a severance package between $34 million and $50 million and be allowed to join another company—especially one that was HP’s competitor in important business lines—just a month later? Although California law makes noncompetition agreements nearly impossible to enforce, investors believed HP should have found some way to ensure that Mr. Hurd would not join the competition.

The next day HP sued Oracle, and asked the court for an injunction preventing Mr. Hurd from starting at his new position. The lawsuit said,

Hurd’s position as a President and a member of the Board of Directors for Oracle puts HP’s trade secrets and confidential information in jeopardy. He will be responsible, in whole or in part, for the direction of the company. As a competitor of HP, he will necessarily call upon HP’s trade secrets and confidential information in performing his job duties for Oracle.21

Investors, for their part, wondered why HP hadn’t thought about that before, but saw the lawsuit as an unnecessary distraction. Investment analyst Felix Salmon blasted the HP board in the investment newsletter Seeking Alpha:

What on earth is the point of Hewlett-Packard suing Mark Hurd? The mutual mudslinging has been decidedly unedifying to date, and now it’s certain to get much worse—and to take place in open court, to boot. With a market capitalization of over $90 billion, suing its former CEO certainly isn’t going to move the needle financially. And it’s going to take up a large amount of the valuable time not only of HP’s executives but of HP’s board members too.

I don’t know who made the decision to launch this lawsuit, but it looks very much like it was filed in a fit of passion after hearing that Hurd had signed on with Oracle. There’s no tactical or strategic rationale for this: it’s just petulance, really.

Does HP even have a chairman right now? It definitely needs one: a grown-up who can tell these people to put away their silly squabbles and concentrate on actually running their business. This lawsuit might be a distraction for Hurd, but it’s going to be much more of a distraction in HP’s executive suite. Basta. Please.22

Oracle shot back with its own criticism of HP’s board. In a press release Oracle CEO Larry Ellison said,

Oracle has long viewed HP as an important partner.... By filing this vindictive lawsuit against Oracle and Mark Hurd, the HP board is acting with utter disregard for that partnership, our joint customers, and their own shareholders and employees. The HP Board is making it virtually impossible for Oracle and HP to continue to cooperate and work together in the IT marketplace.23

HP stock fell about 4 percent on the news of the lawsuit. Two weeks later the two companies settled. CNET, the technology newsletter, speculated about the real reason for the lawsuit:

The terms of the settlement are confidential, according to an HP spokesperson. HP said today that Hurd, now co-president of Oracle, has agreed to “adhere to his obligations to protect HP’s confidential information while fulfilling his responsibilities at Oracle.” But an SEC filing today gives away the real resolution: Hurd agreed to return some of the stock he was granted while still employed by HP.24

In other words, HP convinced Mr. Hurd to soften the blow of his massive severance package.

The board was busy that month. Just ten days after settling the lawsuit, HP announced a new CEO: Léo Apotheker, who had previously served as CEO of the German software giant SAP. The board also elected Ray Lane as non-executive chairman. Mr. Lane, a venture capitalist, had once been president of Oracle.

Mr. Apotheker was a curious choice. The circumstances of the board hiring him weren’t known at the time, but a year later, when rumors swirled of Mr. Apotheker’s pending demise, James B. Stewart put the pieces together in the New York Times, raising further questions about the leadership ability of the HP board:

The mystery isn’t why Hewlett-Packard is likely to part ways with its chief executive, Léo Apotheker, after just a year in the job. It’s why he was hired in the first place. The answer, say many involved in the process, lies squarely with the troubled Hewlett-Packard board.... Interviews with several current and former directors and people close to them involved in the search that resulted in the hiring of Mr. Apotheker reveal a board that, while composed of many accomplished individuals, as a group was rife with animosities, suspicion, distrust, personal ambitions and jockeying for power that rendered it nearly dysfunctional.25

Mr. Stewart noted that when the four-member search committee nominated three finalists to the full board, the other board members declined to meet with any of the finalists. And when the committee recommended Mr. Apotheker, none of the other directors chose to meet with him. So the new CEO was hired after only one-third of the board had met him. One former board member told Mr. Stewart, “I admit it was highly unusual. But we were exhausted from all the infighting.”26

There was no particular reason to rush the decision. The board could have waited, either to meet with Mr. Apotheker or to explore additional candidates. But the board, according to Mr. Stewart, decided to go with the best choice of a very unattractive group. The announcement was made on September 30, and noted that the new CEO and new chairman would start on November 1.27

Investor reaction was immediately negative. Mr. Apotheker had left SAP after only 7 months as CEO, embroiled in a scandal involving alleged theft of trade secrets and copyright infringements from Oracle. He was virtually unknown in the U.S.

Fortune magazine editor at large Adam Lashinsky pointed to the integrity questions that led to his departure from SAP and noted that Mr. Apotheker didn’t have experience in the middle market or in the consumer market, where HP is strong.

HP’s board of directors could have taken the easy way. It could have named a CEO with a proven track record of growth or innovation. Experience that spanned the bulk of HP’s revenue base would have been a plus too. It could have promoted someone from within. It might have found a young, up-and-coming executive at a major competitor who was champing at the bit to be a CEO but was blocked by one of the old guys at the top. It could have found someone with a job. It didn’t.28

Mr. Lashinsky quoted one European investor as saying the appointment was “idiotic”; an American software executive said it was “astonishing.” HP stock fell about 4 percent in the two days following the announcement.

This is yet another demonstration of communication being a leading indicator: If they had thought through the likely stakeholder reaction to Mr. Apotheker, the board could have found ways to neutralize the objections in advance, or revisited their own decision-making process.

Mr. Apotheker didn’t get off to a good start, and his reign was rocky.

He had been on the job less than a week when the Wall Street Journal published a bombshell: a story about Mr. Hurd’s final days based on unnamed sources and recounting confidential board discussions, the contents of Ms. Allred’s letter, and discussions between the board and Mr. Hurd. Some of the details were genuinely alarming; some were tawdry.

In particular, the story said that Mr. Hurd had told Ms. Fisher that HP was in confidential discussions to buy Electronic Data Systems Corp. (EDS) several weeks before the deal was announced. If true, that put Mr. Hurd at risk of a charge of insider trading. Mr. Hurd denied the allegation, and the board seemed inclined to believe him. But the story said that the main reason the board lost trust was in his account of his relationship with Ms. Fisher:

In one previously undisclosed example: The CEO had told directors he didn’t know Ms. Fisher acted in adult movies, say people briefed on the matter, but investigators hired by H-P learned he had visited Web pages showing her in pornographic scenes.... Another: Mr. Hurd told the board he didn’t know Ms. Fisher well; later, in talking to investigators hired by H-P, he said they had a “very close personal relationship.”29

Stakeholders’ reaction to these disclosures was surprisingly positive. Finally, after months of speculation and an intangible feeling that the stated reasons for Mr. Hurd’s departure didn’t add up, they seemed to understand the reasons the board had lost confidence in Mr. Hurd. The new revelations caused even prior critics to say that terminating Mr. Hurd seemed like the right call. What hadn’t made sense in August made sense now, because investors now had a more complete picture.

Commentator Henry Blodget, who had been sharply critical of the board, wrote in Business Insider,

After months of being pummeled for firing financially successful CEO Mark Hurd, HP’s board has finally done what it should have done at the beginning: Tell the whole story....

They couldn’t prove he was lying, but his story shifted enough over the course of the investigation that they no longer believed his denials. And so they canned him.

And under the same circumstances, any competent board would have done the same. Believing that an employee is lying to you, even when you can’t prove it, is more than enough grounds for termination. Because this particular employee had a contract that presumably specified that he could only be fired for “cause,” the board was presumably (and justifiably) worried that it would not be able to prove the “cause” if the case ever ended up in court. And that explains Hurd’s huge severance payment....

The one thing every employee needs to do is maintain the trust and support of the people he or she works for. Mark Hurd failed to do that. And for that he has only himself to blame.30

In other words, given what the board knew at the time, terminating Mr. Hurd was a common-sense thing to do. Mr. Blodget did criticize the board for not having communicated better and sooner:

The HP board did blow it here, in several respects. But based on the details in the WSJ, the errors appear to have been in how the board negotiated the severance and communicated the reasons for Hurd’s termination rather than the termination itself.31

Commentator Jay Yarrow, also writing in Business Insider, echoed Mr. Blodget and summarized the prevailing sentiment that day:

Finally! We now know the really real reason Mark Hurd was tossed from HP. And it finally makes sense.32

Maureen O’Gara wrote on the technology portal SysCon:

An allegation of disclosing inside information has now been added to the otherwise flimsy story of why the HP board asked for the resignation of its star CEO Mark Hurd in August. It’s the first thing that makes any sense in this whole benighted tale.33

Those comments immediately raise questions about whether and how the board might have been able to disclose more than it did in its initial announcement. Once stakeholders understood the reasons for the board’s loss of trust in the CEO, the dismissal made sense. But none of that was conveyed on August 6. It took a leak of confidential board deliberations, by unnamed sources two months later, to set the record straight.

Several months later, HP’s board went through a shake-up. HP announced the appointment of five new board members and the departure of four current members at the spring annual meeting. So the board would briefly expand to 17, then shrink to 13. The new directors were widely viewed as bringing adult supervision to a very dysfunctional board. They included Meg Whitman, former eBay CEO who had just run unsuccessfully for governor of California, plus several other seasoned and experienced executives. Among those leaving were board members who had been seen by their colleagues to be particularly contentious.34

In late February HP announced disappointing sales forecasts, and the stock fell about 13 percent. Three months later it fell another 8 percent when the company announced is first-quarter results.

By the summer of 2011, Mr. Apotheker was struggling, and was severely criticized for several strategic decisions and the way they were communicated. He pulled the plug on the company’s TouchPad—its answer to Apple’s iPad—after only about a month on the market, and said the company would exit the business of smartphones and mobile devices. He later had to clarify that the smartphone software business would remain, and would be licensed to other hardware makers. HP confirmed plans to acquire the British software firm Autonomy for nearly $12 billion, in what one investment analyst called a “value destroying deal.” But most significantly, he announced the possibility of HP selling or spinning off its personal computer business. The head of the PC division got only 24 hours’ notice that such a change was being considered. Big corporate customers were concerned, worrying about the reliability of the supply of HP computers. Dartmouth College Tuck School of Business professor M. Eric Johnson told the New York Times that the communication of the new strategy “was botched in a big, big way.... It came out in dribs and drabs in a very confusing set of announcements.”35

By late August, just a year after Mr. Hurd left, investors had had enough. Reuters reported that Mr. Apotheker’s credibility with investors was plummeting along with its stock price:

In a resounding rejection of Apotheker’s grand vision, shareholders sent HP shares down almost 20 percent on Friday, wiping out $16 billion of value in the worst single-day fall since the Black Monday stock market crash of October 1987.

Since Apotheker joined HP early last November, the company has lost almost 44 percent of its value, and he has lost a significant amount of investor support. “We wonder whether activist investors will—and should—begin to exert pressure on the board,” said Toni Sacconaghi, an analyst with Sanford Bernstein. “If HP’s results don’t improve, the company will ultimately restructure its portfolio and/or replace its leadership.”

Pat Becker, Jr., fund manager at Portland, Oregon–based Becker Capital Management Inc., which owns HP shares, noted that Apotheker has continually failed to instill confidence in his conference calls with investors. “Every time he has gotten on the call, the stock has gone down substantially,” Becker said.36

Within a month Mr. Apotheker was out. He had received a $4 million signing bonus and a salary of $1.2 million, and would walk away with an additional $25 million in cash and stock as severance. Rumors of Mr. Apotheker’s impending departure sent the stock up nearly 7 percent.

On September 22 HP announced that Mr. Apotheker had been fired and would be replaced by board member and former eBay CEO Meg Whitman.37 A month later Ms. Whitman announced that HP would keep its PC business, and the stock rallied, rising nearly 9 percent.38

In the 13 months between Mark Hurd’s departure and Meg Whitman’s arrival as CEO, HP stock went from just under $46 to just above $23 per share, a loss of nearly half its value, representing $46.72 billion in market capitalization.

At every step in its decision making and communication, from Mr. Hurd’s termination to Ms. Whitman’s hiring, the HP board seemed to be acting on impulse, communicating without thinking. It didn’t seem to be weighing options, considering stakeholder perspectives. By leaving gaping holes in its account of what it was doing and why, it left investors scratching their heads and selling their shares. It allowed negative information to dribble out, prolonging news cycles and diminishing loyalty, trust, and confidence. And the only public communication that gave stakeholders any comfort was unofficial, leaked, and anonymous.

Any corporate board’s first responsibilities are to its investors, whose interests it is supposed to protect. By any measure the HP board failed dismally in its leadership duties. Indeed, former HP board member Tom Perkins, who resigned in 2006 in protest of the pretexting scandal, told the New York Times in 2011 that HP “has got to be the worst board in the history of business.”39

In particular, the HP board’s frame of reference seemed to be purely tactical: What do we do now? It didn’t seem to be goal-oriented, or based on a strategy. If anything, it resembled the arcade game Whac-a-Mole, in which you smack a critter that pops out of a hole, only to have another one pop out somewhere else; you smack that one only to have yet another pop out; and so on. It was purely responsive. The board didn’t recognize that its leadership duty is to keep its eye on the horizon, to make choices and to communicate in ways that move the organization in the right direction. In other words, it needs to be strategic.

Understanding Strategy: Thinking Clearly on Three Levels

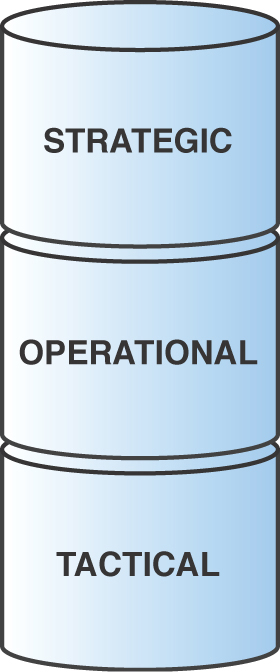

Strategy is the process of ordered thinking: of thinking in a particular order. Effective leaders never confuse means with ends, goals and strategies with tactics. The key is to have clarity about the situation as it presents itself, the goal one is trying to accomplish, and the means by which one will accomplish it. As Figure 6.1 shows, the strategic, operational, and tactical level have an order of priority. The strategic comes first.

Figure 6.1 Hierarchy of war/communication.

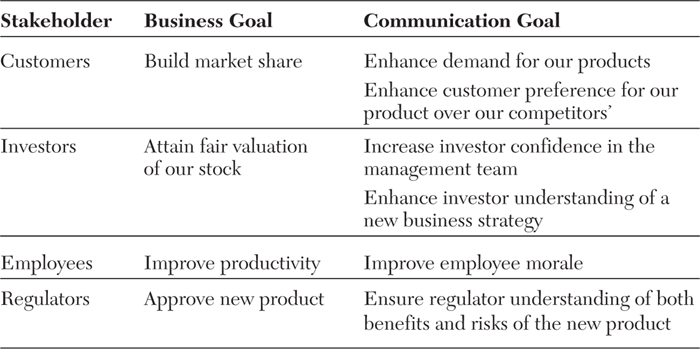

Communication cannot be crafted in a vacuum. All communication tactics (the specific engagements with stakeholders) need to be directly supportive of communication goals (the outcomes we want to achieve). Communication goals, in turn, need to support business goals. Any communication goals or tactics conceived or executed in the absence of clearly defined business goals are likely to be ineffective. The business goals describe changes or outcomes in the business environment or in a company’s competitive position: build market share, attain fair stock market valuation, enhance employee productivity, secure regulatory approval of a new product, and the like. The communication goals describe changes in stakeholder attitudes, feelings, understanding, knowledge, or behavior. Each needs to be clearly articulated, with communication goals subordinate to, and supportive of, the business goals. There will be other ways to achieve the business goals, but communication should make the attainment of those goals faster and easier. Table 6.1 shows how business and communication goals align.

Table 6.1 Aligning Business and Communication Goals

As a goal-oriented activity, all communication must be directly supportive of a goal. That communication goal, in turn, needs to have a clear line of sight to a business goal: If we accomplish the communication goal, we will be more likely—all else being equal—to achieve the business goal faster and more efficiently.

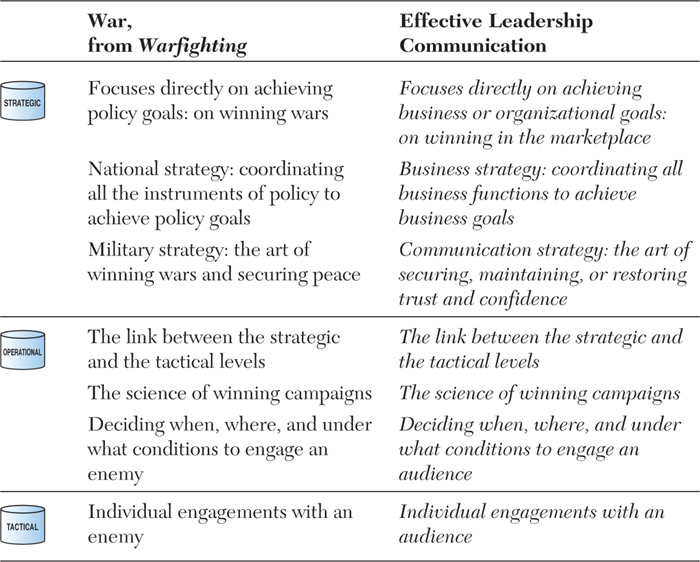

Warfighting gives us a way not only to understand goals, but to understand the organization of resources to effectively plan communication.

The Strategic Level

Planning at the strategic level begins with desired outcomes. What do we need our stakeholders to think, feel, know, and do if we are to change the business environment or our competitive position? The more clarity we have about each of these questions, the more likely we are to be able to plan effectively.

The Operational Level

The operational level is where the actual planning of stakeholder engagement takes place. Once we know (from the strategic level) what we want the change in our stakeholders to be, we can then determine the best manner, time, message, and messenger to engage stakeholders. The operational level is where we make choices. Of what to say, of when to say it, and of how to say it. It is at the operational level that we anticipate stakeholder reaction by inventorying their current level of awareness; their concerns, fears, and hopes; and their likelihood to care about our content. It is at this level that we can project alternative ways of engaging, alternative content, and alternative messengers to anticipate reactions and choose the more likely effective path.

It is precisely at the operational level that many leaders and leadership teams fall short. By failing to anticipate and adapt, they end up speaking in ways that may make them feel better but that aren’t necessarily going to move stakeholders the way we need them to be moved.

The Tactical Level

The tactical level is where communication actually takes place. Tactics are the ways we talk to people, what we actually say to them, the contact we actually make. The tactical level is where we have the press release, the speech, the employee e-mail, the press conference.

Most leaders default to the tactical as a first resort. HP’s board certainly seemed to. But the tactical must be in the service of the operational, which in turn is in the service of the strategic. Rather than default to the tactical, effective leaders get to the tactical by considering the other levels first. Table 6.2 illustrates the ways the strategic, operational, and tactical relate in communication planning.

Table 6.2 The Three Levels of War/Communication

To communicate effectively, we need to understand what we are trying to achieve.

Unity of effort is alignment of all communication tactics and messages. Consider, for example, the initial inconsistencies in HP’s first-day communications. Three different public statements gave three slightly different accounts of the reasons for Mr. Hurd’s departure. But none of them was sufficient to satisfy stakeholders that it was the right move on the part of the company.

Think also of the focus discussed in Chapter 4, “Speed, Focus, and the First Mover Advantage.” All Marine Corps communication in the aftermath of the Fallujah mosque shooting was well-coordinated, consistent, and in line with stakeholders’ reasonable expectations of what a responsible organization would do when confronted with such a situation. The U.S. military’s response in the aftermath of the abuse of prisoners at Abu Ghraib was not. That response also seemed purely tactical, unfocused, and uncoordinated, and it failed to meet the appropriate expectations of stakeholders.

Unity of effort in the service of clearly defined goals, with an operational framework that makes smart choices about what to say, when, how, and to whom, is the key to effective leadership communication.

Template for Planning: For Being Strategic in Leadership Communication

The three levels from Warfighting— the strategic, the operational, and the tactical—lead to a framework for effective communication planning.

Here’s a planning template that can help leaders be strategic in preparing and planning for communication. It’s the template I use with my clients and students to help them think through communication with the goal in mind.

Recap: Best Practices from This Chapter

Refer back to Table 6.2 for a recap of the three levels of war/communication.

Lessons for Leaders and Communicators

Planning isn’t scheduling events on a calendar, but rather working on a chessboard to anticipate stakeholder reactions several moves ahead. As in the rule from carpentry—measure twice, cut once—we need to be so well prepared at the moment of execution that we get the communication right the first time.

The key to planning is projecting thoughts forward: our own thoughts and our stakeholders’ thoughts. Because all communication is a process of continuous mutual adaptation, we need to consider our stakeholders’ reaction before we communicate with them. The first mover advantage can work only if we say what is sufficient to neutralize their concerns before they arise. The rule of thumb in communicating bad news includes the following:

• Tell it all—say all that is necessary to establish stakeholder understanding, buy-in, or neutrality.

• Tell it fast—bundle the bad news into a single news cycle, and avoid dripping out new details over time, which creates a new news cycle and causes stakeholders to question the leadership skills of those communicating.

• Tell ’em what you’re doing about it.

• Tel ’em when it’s over.

• Get back to work.

Planning communication is important for reasons beyond public relations. It can also provide clarity in decision making. The very process of considering likely reactions to proposed communications can reveal failures of planning in the actual business decision making. In other words, communication planning serves as a leading indicator that something is amiss, and the need to explain something often calls attention to some inconsistency in a leader’s thought process.

Strategy is the process of ordered thinking—of thinking in a particular order. Effective leaders never confuse means with ends, tactics with goals and strategies. The key is to have clarity about the situation as it presents itself, the goal one is trying to accomplish, and the means by which one will accomplish them.

All communication tactics (the specific engagements with stakeholders) need to be directly supportive of communication goals (the outcomes we want to achieve). Communication goals, in turn, need to support business goals. Any communication goals or tactics conceived or executed in the absence of clearly defined business goals are likely to be ineffective. The business goals describe changes or outcomes in the business environment or in a company’s competitive position: build market share, attain fair stock market valuation, enhance employee productivity, secure regulatory approval of a new product, and the like. The communication goals describe changes in stakeholder attitudes, feelings, understanding, knowledge, or behavior. Each needs to be clearly articulated, with communication goals subordinate to, and supportive of, the business goals. There will be other ways to achieve the business goals, but communication should make the attainment of those goals faster and easier.

Planning at the strategic level begins with clarity about the situation and the desired outcomes. What do we need our stakeholders to think, feel, know, and do if we are to change the business environment or our competitive position? The more clarity we have about each of these questions, the more likely we are to be able to plan effectively.

The operational level is where the actual planning of stakeholder engagement takes place. Once we know (from the strategic level) what we want the change in our stakeholders to be, we can then determine the best manner, time, message, and messenger to enage stakeholders. The operational level is where we make choices. Of what to say, or when to say it, and of how to say it. It is at the operational level that we anticipate stakeholder reaction by inventorying their current level of awareness; their concerns, fears, and hopes; and their likelihood to care about our content. It is at this level that we can project alternative ways of engaging, alternative content, and alternative messengers to anticipate reactions and choose the more likely effective path.

It is precisely at the operational level that many leaders and leadership teams fall short. By failing to anticipate and adapt, they end up speaking in ways that may make them feel better but that aren’t necessariliy going to move stakeholders the way we need them to be moved.

The tactical level is where communication actually takes place. Tactics are the things we actually say to people, the contact we actually make. The tactical level is where we have the press release, the speech, the employee e-mail, the press conference.

Most leaders default to the tactical as a first resort. HP’s board certainly seemed to. But the tactical must be in the service of the operational, which in turn is in the service of the strategic. Rather than defaulting to the tactical, effective leaders get to the tactical by conisdering the other levels first.

Unity of effort in the service of clearly defined goals, with an operational framework that makes smart choices about what to say, when, how, and to whom, is the key to effective leadership communication.

From Warfighting

From Warfighting