Chapter Seven

Corporate Ethics: Good Governance

WHAT IS CORPORATE GOVERNANCE?

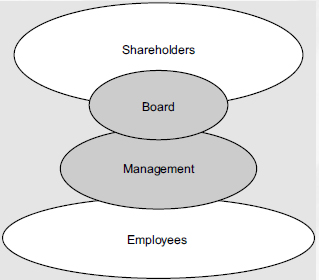

Corporate governance is typically perceived by academic literature as dealing with “problems that result from the separation of ownership and control.”1 From this perspective, corporate governance would focus on: The internal structure and rules of the board of directors; the creation of independent audit committees; rules for disclosure of information to shareholders and creditors; and, control of management. Figure 7.1 explains how a corporation is structured.

Fig. 7.1 Separation of Ownership and Management

DEFINITIONS OF CORPORATE GOVERNANCE

Though the concept of corporate governance sounds simple and unambiguous, when one attempts to define it and scan the available literature to look for precedence, one comes across a bewildering variety of perceptions behind the available definitions. The definition varies according to the sensitivity of the analyst, the context of varying degrees of development, and from the standpoint of academics versus corporate managements. However, there is an underlying uniformity in the thinking of all analysts that there is a definite need to eradicate corporate misgovernance and promote corporate governance at all costs. It is not only the stakeholders who are keenly interested in ensuring adoption of best governance practices by corporations, but also societies and countries worldwide.1

Sir Adrian Cadbury, Chairman of the Cadbury Committee defined the concept thus: “Corporate governance is defined as holding the balance between economic and social goals and between individual and communal goals. The governance framework is there to encourage the efficient use of resources and equally to require accountability for the stewardship of those resources”. The objective of corporate governance is to ensure, as far as possible, the interests of its stakeholders—enable individuals, corporations and society. It will enable corporations realize their aims and attract investment. From the standpoint of States, it will strengthen their economies, even while discouraging fraud and mismanagement.2

Experts at the Organization of Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) have defined corporate governance as “the system by which business corporations are directed and controlled”. The structure of corporate governance, according to them, “specifies the distribution of rights and responsibilities among different participants in the corporation, such as, the board, managers, shareholders and other stakeholders, and spells out the rules and procedures for making decisions on corporate affairs”. Such specifications define company objectives, provide a means to achieve the objectives and monitors performance.3 OECD’s definition, incidentally is consistent with the one presented by the Cadbury Committee.

These definitions which are shareholder-centric capture some of the most important concerns of governments in particular and the society in general. These are (i) management accountability; (ii) providing adequate investments to management; (iii) disciplining and replacement of bad management; (iv) enhancing corporate performance; (v) transparency; (vi) shareholder activism; (vii) investor protection; (viii) improving access to capital markets; (ix) promoting long-term investment; and (x) encouraging innovation.

According to the World Bank corporate governance can be defined from two aspects, namely, corporation and public policy. Defining from the perspective of a corporation, corporate governance is relations between owners, management board and other stakeholders (the employees, customers, suppliers, investors and communities) where emphasis is given to the board of directors to balance their interests to achieve long-term sustained value. From a public policy perspective, corporate governance refers to providing for the survival, growth and development of the company, and at the same time, its accountability in the exercise of power and control over companies. The role of public policy is to discipline companies and simultaneously initiate minimization of differences between private and social interests.4 The OECD also offers a broader definition: “ … Corporate governance refers to the private and public institutions, including laws, regulations and accepted business practices, which together govern the relationship in a market economy, between corporate managers and entrepreneurs (‘corporate insiders’) on one hand, and those who invest resources in corporations, on the other.”5

Fewer concerns are more critical to international business and developmental strategies than that of corporate governance. A series of events over the last two decades have placed corporate governance issues at centre stage as of paramount importance both for the international business community and financial institutions. It has become the cynosure of all issues connected with corporations. Successive business failures and frauds in the United States, several high-profile scandals in Russia and the Asian crisis have brought corporate governance issues to the forefront in developing countries and transitional economies. Further, national business communities are gradually realizing the fact that there is no substitute for getting the basic business and management systems in place in order to be competitive in the global market and to attract investment.

DESIDERATA OF CORPORATE GOVERNANCE

The OECD has emphasized the following requirements of corporate governance:

Rights of Shareholders

The rights of shareholders that have been stressed as important for ensuring better corporate governance by all writers and organizations including the World Bank and Asia Pacific Economic Cooperation (APEC) include secure ownership of their shares, voting rights, the right to full disclosure of information, participation in decisions on sale or any change in corporate assets (including mergers) and new share issues. Shareholders have the right to know the capital structures of their corporation and arrangements that enable certain shareholders to obtain control disproportionate to their holding. All transactions should be at transparent prices and under fair conditions. Anti-takeover devices should not be used to shield the management from accountability. Institutional shareholders should consider the costs and benefits of exercising their voting rights.

Equitable Treatment of Shareholders

The OECD and other organizations such as the APEC have stressed the point that all shareholders including minority and foreign shareholders should get equitable treatment and have equal opportunity for redressal of their grievances and violation of their rights. Shareholders should not face undue difficulties in exercising their voting rights. Any change in their voting rights should be subject to a vote by shareholders. Insider trading and abusive self-dealing that are repugnant to the principle of equitable treatment of shareholders should be prohibited. Directors should disclose any material interests regarding transactions. They should avoid situations involving conflict of interest while making decisions. Interested directors should not participate in deliberations leading to decisions that concern them.

Role of Stakeholders in Corporate Governance

The OECD guidelines, as also others on the subject of corporate governance, recognize the fact that there are other stakeholders in corporations apart from shareholders. Apart from dealers, consumers and the government who constitute the stakeholders’ group, there are others too who ought to be considered. Banks, bondholders and workers, for example, are important stakeholders in the way in which companies perform and make decisions. Corporate governance framework should, apart from recognizing the rights of shareholders, allow employee representation on the board of directors, profit sharing, creditors’ involvement in insolvency proceedings, etc. Where there is such stakeholder participation, it should be ensured that they have access to relevant information.

Disclosure and Transparency

The OECD lays down a number of provisions for the disclosure and dissemination of key information about the company to all those entitled for such information. These may range from company objective to financial details, operating results, governance structure and policies, the board of directors, their remuneration, significant foreseeable risk factors and material issues regarding employees and other stakeholders. The OECD guidelines also spell out that annual audits should be performed by independent auditors in accordance with high quality standards.

Like the OECD, the APEC also provides guidelines on the establishment of effective and enforceable accountability standards, timely and accurate disclosure of financial and non-financial information regarding company performance.

Responsibilities of the Board

The OECD guidelines explain in detail the functions of the board in protecting the company, its shareholders and its other stakeholders. These functions would include concerns about corporate strategy, risk, executive compensation and performance, accounting and reporting systems, monitoring effectiveness and changing them, if needed.

APEC guidelines include establishment of rights and responsibilities of managers and directors.

The OECD guidelines focus only on those governance issues that arise due to separation between ownership and control of capital. Though these have limited focus, they are comprehensive, especially with reference to voting rights of institutional shareholders and obligations of the board to stakeholders. Though the APEC principles too reiterate them, they give foremost importance to disclosures. Again, instead of rights of shareholders, they reiterate the rights and also of the responsibilities of shareholders, managers and directors. To them, establishment of accountability standards is a separate principle by itself.

The broad objectives and principles of corporate governance may be the same to all societies, but when it comes to applying them to individual countries we have to reckon the peculiar features, socio-cultural characteristics, the history of its people, their value systems, economic system, political set-up, stage and maturity of development and even literacy rates. All these factors have an impact on both political and corporate governance systems. Superimposing the governance systems and procedures that are effective in mature Western democracies on transition economies will be inappropriate, ineffective and may even be inimical to the interests of the people these are intended to serve.

A HISTORICAL PERSPECTIVE OF CORPORATE GOVERNANCE

The seeds of modern ideas of corporate governance were probably sown by the Watergate scandal during the Nixon presidency in the United States. The need to arrest such unhealthy trends was translated into the legislation of the Foreign and Corrupt Practices Act of 1977 in America that provided for the establishment, maintenance and review of systems of internal control. In the same year, the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) proposed mandatory reporting on internal financial controls. In 1985, a series of high-profile business failures rocked the United States, which included the collapse of Savings and Loan. With a view to identifying the main causes of misrepresentation in financial reports and to recommend ways of reducing such incidences, the government appointed the Treadway Commission. The Treadway Report, published in 1987, highlighted the need for a proper control environment, independent audit committees and an objective internal audit system. As a result of this recommendation, the Committee of Sponsoring Organizations (COSO) came into being. COSO’s report in 1992 stipulated a control framework for the orderly functioning of corporations. Between the period 2000 and 2002, the revelations of corporate fraud in the United States were of such magnitude and inflicted such damage on investors that company reputations were irreparably destroyed and investor confidence dipped to a new low. The fraud and self-dealing revelations resulted in investigations by the Congress, the SEC, and the State Attorney General in New York and the emergence of the Sarbanes-Oxley Act (SOA) enacted into law on 30 July 2002.

A series of corporate scams and collapses in the late 1980s and the early 1990s made the United Kingdom realize that the existing rules and regulations were inadequate to curb unlawful and unfair practices of corporations. It was with this view a committee under the chairmanship of Sir Adrian Cadbury was appointed by the London Stock Exchange in 1991. The Cadbury Committee, consisting of representatives drawn from the echelons of British industry, was assigned the task of drafting a code of practices to assist corporations in England in defining and applying internal controls to limit their exposure to financial loss, from whatever cause it arose. The committee submitted its report along with the ‘Code of Best Practices’ in December 1992. In its globally well-received report, the committee elaborated the methods of governance needed to achieve a balance between the essential powers of the board of directors and their proper accountability. Though the recommendations of the committee were not mandatory in character, the companies listed on the London Stock Exchange were enjoined to state explicitly in their accounts, whether or not the code has been followed by them, and if not complied with, were advised to explain the reasons for non-compliance.

In India, the real history of corporate governance dates back to the year 1992, following efforts made in many countries of the world to put in place a system suggested by the Cadbury Committee. The corporate governance movement in India began in 1997 with a voluntary code framed by the Confederation of Indian Industry (CII). In the next three years, almost 30 large listed companies accounting for over 25 per cent of India’s market capitalization voluntarily adopted the CII code. This was followed by the recommendations of the Kumar Mangalam Birla Committee set up in 1999 by the Securities and Exchange Board of India (SEBI), culminating in the introduction of Clause 49 of the standard Listing Agreement to be complied with by all the listed companies in stipulated phases. The Kumar Mangalam Birla Committee divided its recommendations into mandatory and non-mandatory. Mandatory recommendations included such issues as the composition of board, appointment and structure of audit committees, remuneration of directors, board procedures, additional information regarding management, discussion and analysis as a part of the annual report, disclosure of directors’ interest, shareholders’ rights and the compliance level of corporate governance in the annual report. From 1 April 2001, over 140 listed companies accounting for almost 80 per cent of market capitalization were to follow a mandatory code which was in line with some of the best international practices. By April 2003, every listed company followed the SEBI code.

The Companies Amendment Act, 2000

Many provisions relating to corporate governance such as additional ground of disqualification of directors in certain cases, setting up of audit committees, Directors’ Responsibility Statement in the Directors’ Report, etc. were introduced by the Companies (Amendment) Act, 2000. Corporate governance was also introspected in 2001 by the Advisory Group constituted by the Standing Committee on International Finance Standards and Codes of the Reserve Bank of India under the chairmanship of Dr Y. V Reddy, the then Deputy Governor.

Naresh Chandra Committee, 2002

In the year 2002, a high-level committee was appointed to examine and recommend drastic amendments to the law involving the auditor-client relationships and the role of independent directors by the Department of Company Affairs in the Ministry of Finance and Company Affairs under the chairmanship of Naresh Chandra.

Narayana Murthy Committee, 2003

The Company Law Amendment Bill, 2003 envisaged many amendments on the basis of reports of the Naresh Chandra Committee and subsequently appointed the N. R. Narayana Murthy Committee. Both the committees have done an excellent job to promote corporate governance practices in India.

Dr J. J. Irani Committee Report on Company law, 2005

The Government of India constituted an Expert Committee on Company Law on 2 December 2004 under the Chairmanship of Dr J. J. Irani. Set up to structurally evaluate the views of several stakeholders in the development of company law in India in respect of the concept paper promulgated by the Union Ministry of Company Affairs, the J. J. Irani committee has made suggestions to reform and update the basic corporate legal framework essential for sustainable economic reform. The report has taken a pragmatic approach keeping in view the ground realities, and has sought to address the concerns of all the stakeholders to enable the adoption of internationally accepted best practices.

Recommendations of the J. J. Irani Committee

Some of the most significant recommendations of the Irani committee are:

- One-third of the board of a listed company should comprise independent directors.

- Allow pyramidal corporate structures, that is, a company which is a subsidiary of a holding company coul itself be a holding company.

- Give full liberty to the shareholders and owners of the company to operate in a transparent manner.

- The new company law should recognize principles such as ‘class actions’ and ‘derivative action’. There are proposals to devise an exit option for shareholders who have stayed with a company and not participated in a buy back scheme implemented earlier.

- Introduce the concept of One Person Company (OPC) as against the current stipulation of at least two persons to form a company.

- Allow corporations to self-regulate their affairs.

- Mandate publication of information relating to convictions for criminal breaches of the Companies Act on the part of the company or its officers in the annual report. Provide stringent penalties to curb fraudulent behaviour of companies.

- Disclose proper and accurate compilation of financial information of a corporation.

The history of corporate governance gives us an unforgettable lesson that vigilance and a continuing effort at building and strengthening it alone will give the investors the safetynet they require.

SIGNIFICANCE OF CORPORATE GOVERNANCE TO DEVELOPING COUNTRIES

Just as several developing countries are undergoing a process of economic growth, they are also witnessing a transformation in political and business relationships with regard to their industrial and commercial organizations, both in the private and public sectors. Economic and political compulsions are forcing them to move away from the hitherto closed, market-unfriendly and undemocratic set-ups to open, transparent, market-driven democratic systems. If they have to sustain long-term economic growth and development in such a situation, it is important that they establish good corporate governance mechanisms and practices that will enable their organizations realize maximum productivity and economic efficiency. Corporate governance systems and practices also will help them fight effectively corruption and abuse of power that are rampant in their societies and help them establish a system of managerial competence and accountability.

Nicolas Meisel has identified four priorities developing countries should concentrate on when they put into practice new forms of public and corporate governance. These are (i) since good and effective communication is a desideratum for the efficient functioning of any organization, they should not only enhance the quality of information, but also ensure that it is created fast and reaches the public speedily; (ii) ensure individual players maximum autonomy while seeing that they are accountable for their acts; (iii) if there is a hierarchical set-up to regulate private sector activities with a view to promoting public interest, new counterveiling powers should be set-up to fill this role; and (iv) the role of the State and how government officials are appointed to carry out the role, should be clearly defined in the interest of sustainable development.6

ISSUES IN CORPORATE GOVERNANCE

Corporate governance has been defined in different ways by different writers and organizations. Some define it in a narrow perspective to include in it only the shareholders, while others want it to address the concerns of all stakeholders. Some talk about corporate governance as being an important instrument for a country to achieve sustainable economic development, while some others consider it as a strategy for a corporate to achieve a long tenure and a healthy image. To people in developing societies and transitional economies, it is a necessary incentive to usher in more powerful and vibrant institutions of control. To some, it provides another dimension to corporate ethics and social responsibility of business. Thus corporate governance has become several things to several people. But to all, corporate governance is a means to an end, the end being long-term shareholder, and more importantly, stakeholder value. Thus, all authorities on the subject are one in recognizing the need for good corporate governance practices to achieve the end for which corporations are formed. They identify some governance issues as being crucial and critical to achieve these objectives. These are as follows.

Distinguishing the Roles of Board and Management

The constitutions of many companies stress and underline that business is to be managed ‘by or under the direction of’ the board. In such a practice, the responsibility for managing the business is delegated by the board to the CEO, who in turn delegates the responsibility to other senior executives. Thus, the board occupies a key position between the shareholders (owners) and the company’s management (day-to-day managers of the company’s resources). As per this arrangement, the board of a listed company has the following functions:

- select, decide the remuneration and evaluate on a regular basis, and if necessary, change the CEO;

- oversee (not directly, but indirectly) the conduct of the company’s business to evaluate whether or not it is being correctly managed;

- review and, where necessary, approve the company’s financial objectives and major corporate plans and objectives;

- provide advice and counsel to top management;

- select and recommend candidates to shareholders for electing them to the board of directors;

- review the adequacy of systems to comply with all applicable laws and regulations; and

- review any other functions required by law to be performed.

Composition of the Board and Related Issues

The board of directors is a “committee elected by the shareholders of a limited company to be responsible for the policy of the company. Sometimes, full-time functional directors are appointed, each being responsible for some particular branch of the firm’s work.”7

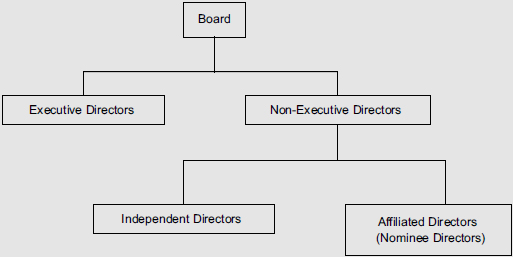

The composition of the board of directors refers to the number of directors of different kinds who participate in the working of the board. Over time there has been a change as to the number and proportion of different types of directors in the board of a limited company. Figure 7.2 illustrates the usual composition of the board in recent times in most of the countries.

The Board of Directors of a company must have a optimum combination of executive and non-executive Directors with not less than 50 per cent of the Board comprising of non-executive Directors. The number of independent Directors should be at least one-third in case the company has a non-executive Chairman and at least half of the Board in case the company has an executive Chairman.

The SEBI-appointed Kumar Mangalam Birla Committee’s report defined the composition of the board thus: “The Committee recommends that the board of a company have an optimum combination of executive and non-executive directors with not less than fifty percent of the board comprising the non-executive directors. The number of independent directors (independence being as defined in the foregoing paragraph) would depend on the nature of the chairman of the board. In case a company has a non-executive chairman, at least one-third of the board should comprise independent directors and in case a company has an executive chairman, at least half of the board should be independent”.8

Fig. 7.2 Types of Directors

As shown in Fig. 7.2, for instance, an executive director is one who is an executive of the company and who is also a member of the board of directors, while a non-executive director has no separate employment relationship with the company. Independent non-executive directors are those directors on the board who are free from any business or other relationship, which could materially interfere with the exercise of their independent judgement in the process of decision making as a member of the board. An affiliated director or a nominee director is a non-executive director who has some kind of independence, impairing relationship with the company or the company’s management. For example, the director may have links with a major supplier or customer of the company, or may be a partner in a professional firm that supplies services to the company, or may be a retired top management professional of the company.9

Separation of the Roles of the CEO and Chairperson

The composition of the board is a major issue in corporate governance as the board acts as a link between the shareholders and the management and its decisions affect the performance of the company. Professionalization of family companies should commence with the composition of the board. All committees that studied governance practices all over the world, starting with the Cadbury Committee, have suggested various improvements in the composition of boards of companies.

It is now increasingly being realized that the practice of combining the role of the chairperson with that of the CEO as is done in countries like the United States and India leads to conflicts in decision making and that too much concentration of power in one person results in unsavoury consequences. In the United Kingdom and Australia, the CEO is prohibited from being the chairperson of the company. The role of the CEO is to lead the senior management team in managing the enterprise, while the role of the chairperson is to lead the board, one of the important responsibility of the board being to evaluate the performance of senior executives including the CEO. Combining the role of both the CEO and chairperson removes an important check on senior management’s activities. Besides, in large corporations, the job of the CEO as well as that of the chairman may be heavy and onerous and one person, with how much ever business acumen and astuteness, may not be able to deliver what he or she is expected to, competently, efficiently and objectively. That is the reason why many authorities on corporate governance recommend strongly that the chairman of the board should be an independent director in order to “provide the appropriate counterbalance and check to the power of the CEO”.10

Should the Board have Committees?

Many committees on corporate governance have recommended in one voice the appointment of special committees for (i) nomination, (ii) remuneration, and for (iii) auditing. These committees would lessen the burden of the board and enhance its effectiveness. According to the Bosch Report, committees, apart from having written terms of reference outlining their authority and duties, “should also have clear procedures for reporting back to the board, and agreed arrangements for staffing including access to relevant company executives and the ability to obtain external advice at the company’s expense.”11

Appointments to the Board and Directors’ Re-election

As per the Company Law, shareholders elect directors to the Board. However, shareholders are a legion in large companies and also scattered, and to have them together to elect the directors will be expensive and time-consuming. Therefore, in actual practice, in most cases, the board or its specially constituted committee selects and appoints the prospective director and gets the person formally “elected” by the shareholders at the ensuing Annual General Body Meeting.

The shareholders in fact only endorse the board’s nominee and it is only in the rarest of rare cases that the shareholders refuse to ratify the board’s nominees for directorship. There are other issues of corporate governance in relation to the boards’ appointments such as: appointment of a nomination committee, terms of office, duties, remuneration and re-election of directors and composition of the board on which several committees have made their own recommendations.

Directors’ and Executives’ Remuneration

This is one of the mixed and vexed issues of corporate governance that first came to the centre-stage during the massive corporate failures in the United States between 2000 and 2002 and later reappeared with renewed vigour during the Wall Street crisis of 2008. Executive compensation has also in recent times become the most visible and politically sensitive issue relating to corporate governance.

The Cadbury Committee Report stressed that shareholders should be informed all details pertaining to board remuneration, especially directors’ entitlements, both present and future, and how these have been determined. Other committees on corporate governance have also laid emphasis on related issues such as ‘pay-for- performance,’ heavy severance payments, pension for non-executive directors, appointment of remuneration committee, and so on. ‘However, while controversy often surrounds the size or quantum of remuneration, this is not necessarily an issue of corporate governance—a payment that may be excessive in one context may be reasonable in another’. More important than the size and quantum of remuneration of top management, key issues of corporate governance would include (i) transparency, (ii) justifiability of the pay in the context of performance, (iii) the process adopted in determining it, (iv) severance payments, and (v) non-executive directors’ pensions.12

Disclosure and Audit

The OECD lays down a number of provisions for the disclosure and communication of ‘key facts’ about the company to its shareholders. The Cadbury Committee Report termed the annual audit as one of the corner stones of corporate governance. Audit also provides a basis for reassurance for everyone who has a financial stake in the company. Both the Cadbury Report and the Bosch Report stressed that the board of directors has a bounden responsibility to present to the shareholders a lucid and balanced assessment of the company’s financial position through audited financial statements. There are several issues and questions relating to auditing which have an impact on corporate governance. There are, for instance, questions such as (i) Should boards establish an audit committee? (ii) If yes, how should it be composed? (iii) How to ensure the independence of the auditor? (iv) What precautions are to be taken or what are the positions of the State and regulators with regard to provision of non-audit services rendered by auditors? (v) Should individual directors have access to independent resource? (vi) Should boards formalize performance standards? These questions are being answered with different perceptions and with different degrees of emphasis by various committees and organizations that have gone into and analysed these issues in depth.

Protection of Shareholder Rights and Their Expectations

This is an important governance issue which has considerable impact on the rights and expectations of shareholders. Corporate practices and policies vary from country to country. There are a number of questions relating to this issue such as: (i) Should companies adhere to one-share-one-vote principle always? (ii) Should companies retain voting by a show of hands or by poll? (iii) Can shareholder resolutions be ‘bundled’? That is, to place together before shareholders for approval a resolution that contains more than one discrete issue. (iv) Should shareholder approval be required for all major transactions? These questions have elicited answers with different emphases from various committees and organizations that have addressed these issues.

Dialogue With Institutional Shareholders

The Cadbury Committee recommends that institutional investors should maintain regular systematic contact with companies, apart from participating in general meetings of shareholders. They should use their voting rights positively, take a positive interest in the composition of the board of directors of companies in which they invest, and above all, recognize their rights and responsibilities as ‘owners’ who should act in the best interests of those whose money they have invested. Tehy should influence the standards of corporate governance by bringing about changes in companies when necessary, rather than by selling their shares. If institutional investors have to exercise their rights and carry out their responsibilities, companies have to provide them the required information and facilities for doing so.

Making a Socially Responsible Corporate—Investor’s Role

This is an issue that highlights a conflict between two schools of thought. One school of thought based on past experience, contends that institutional investors should act in the best financial interests of the beneficiaries. This is based on the assumption that socially responsible behaviour of corporations such as ecological preservation, anti-pollution measures and producing quality and environment-friendly products always enhance costs and thus reduce profits. But there is another school of thought which asserts environment friendliness and economic gains are not contradicting goals, but on the other hand, they benefit corporations in the long run and cite the examples of Ford Motors, Johnson & Johnson, Pfizer to prove their point. Much can be, and is being said, on both sides and though the last word is yet to be said on the issue, present thinking worldwide across continents and divergent societies strongly prefers corporations that are committed to the overall welfare of people in whose midst they work and make their gains.

MAJOR THRUST AREAS OF CORPORATE GOVERNANCE

The latest, revised OECD principles, place their thrust on six major areas of corporate governance: (i) they call upon governments to put in place an effective institutional and legal framework to support good corporate governance practices; (ii) they call for a corporate governance framework that protects and facilitates the exercise of shareholders’ rights; (iii) they strongly support equitable treatment of all shareholders including minority and foreign shareholders; (iv) they recognize the importance of the role of stakeholders in corporate governance; (v) they stress the importance of timely, accurate and transparent disclosure mechanisms; and finally (vi) they deal with board structures, responsibilities and procedures. All issues of corporate governance, of course, emanate from and centre around these six major thrust areas.

Need for and Importance of Corporate Governance

Many large corporations are multinational and/or transnational in nature. This means that these corporations have an impact on citizens of several countries across the globe. If things go wrong, they will affect many countries, albeit some more severely than others. It is, therefore, necessary to look at the international scene and examine possible international solutions to corporate governance difficulties.

Corporate governance is needed to create a corporate culture of consciousness, transparency and openness. It refers to a combination of laws, rules, regulations, procedures and voluntary practices to enable companies to maximize shareholders’ long-term value. It should lead to increasing customer satisfaction, shareholder value and wealth. With increasing government awareness, the focus is shifted from economic to the social sphere and an environment is being created to ensure greater transparency and accountability. It is integral to the very existence of a company.

Governance and Corporate Performance

Several studies in the US have found a positive relationship between corporate governance and corporate performance. That is, improved corporate governance is linked with improved corporate performance—either in terms of rise in share price or profitability. However, it would be overstating the case to say that these studies are conclusive, because other research has either failed to find a link or found it otherwise.

One difficulty in looking for statistical evidence of the value of good corporate governance is that governance is multi-dimensional. There are several different corporate governance mechanisms, which can inter-relate with and, sometimes, substitute for one another.

There are strong signs that the world’s business-ethical standards are becoming more stringent, and what constitutes good business practice is becoming clearer. Eleven years ago, Korn/Ferry International and the Columbia University Business School conducted a 20-country poll on 1,500 business executives. They were asked to look ahead and identify a list of the most important characteristics of the ideal corporate CEO for the year 2000. It was found that ‘ethics’ was right at the top of the list. Not anywhere else, but right at the top. The Conference Board in New York, together with the Institute of Business Ethics in London, did similar studies in 1992, and found 84 per cent of responding US firms had a corporate ethics code, followed by 71 per cent of UK firms, and 58 per cent for the rest. The figure for the UK grew particularly fast; four years earlier, it had been just 55 per cent. It seems that the business stress on ethics is a very Anglo-American phenomenon. As these two countries are arguably the trendsetters in the global economy, their way of doing business would eventually affect the rest of the world and, with innovations and modifications to suit different countries and markets, could even become the global norm.

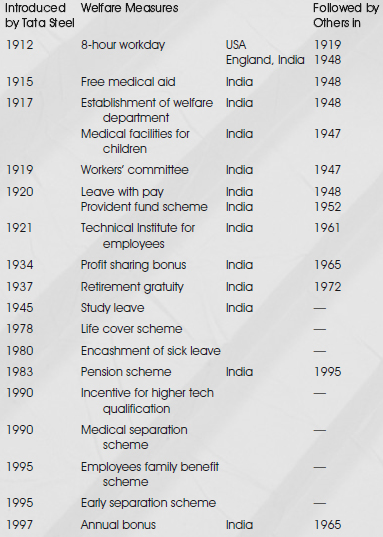

In India too, there are several examples to illustrate the positive relationship between corporate governance and corporate performance, though this is the case with fewer companies and there is a long road to traverse for the entire Indian corporate sector as such. Among companies that have shown commendable success after introducing internationally acclaimed corporate governance practices are: Infosys Technologies Ltd that has consistently enhanced its performance and is a forerunner in espousing global governance standards; Tata Steel that which is recognized and rewarded not only in India, but also globally for its excellent corporate performance social commitment and activism; and Dr. Reddy’s Lab that which has excelled in all the important dimensions of corporate governance. There are several other group of companies belonging to the Tatas, Birlas, Murugappa’s, etc. in the private sector, and the oil companies in the public sector that have done India proud in the sphere of corporate governance.

Investors’ Preference for Good Governance

A recent large-scale survey of institutional investors found that a majority of investors consider governance practices to be at least as important as financial performance when they are evaluating companies for potential investment. Indeed, they would be prepared to pay a premium for shares in a well-governed company compared to a poorly governed company exhibiting familiar financial performance. In the US and the UK, the premium was 18 per cent while it was 27 per cent for Italian and 27 per cent for Indonesian companies (Global Investor Opinion Survey Key Findings, Mc Kinsey & Company, July 2002). Likewise, a survey by Pitabas Mohanty (Institutional Investors and Corporate Governance in India) has revealed that companies with good corporate governance records have actually performed better as compared to companies with poor governance records, and that institutional investors have extended loans to them easily. Another similar survey of institutional investors, globally, has also revealed governance to be an important factor in investment decision making

Significance of Corporate Governance to Developing Countries

Just as several developing countries are undergoing a process of economic growth, they are also witnessing a transformation in political and business relationships with regard to their industrial and commercial organizations, both in the private and public sectors. Economic and political compulsions are forcing them to move away from the hitherto closed, market unfriendly and undemocratic set-ups to an open, transparent, market-driven democratic system. If they have to sustain long-term economic growth and development in such a situation, it is important that they establish good corporate governance mechanisms and practices that will enable their organizations realize maximum productivity and economic efficiency. Corporate governance systems and practices also will help them fight effectively corruption and abuse of power that are rampant in such societies and enable them establish a system of managerial competence and accountability.

Nicolas Meisel has identified four priorities developing countries should concentrate on when they put into practice new forms of public and corporate governance. These are: (1) Since good and effective communication is a desideratum for the efficient functioning of any organization, they should not only enhance the quality of information, but also ensure that it is created fast and reaches the public speedily; (2) Ensure individual players maximum autonomy whilst seeing that they are accountable for their acts; (3) If there is a hierarchical setup to regulate private sector activities with a view to promoting public interest, new countervailing powers should be set up to fill this role; and (4) The role of the State and how government officials are appointed to carry out the role should be clearly defined in the interest of sustainable development (see Note 6).

STRATEGIES AND TECHNIQUES BASIC TO SOUND CORPORATE GOVERNANCE

Having understood the importance and significance of corporate governance to the growth and development of the corporate sector and orderly industrialization of a country, one should learn the various strategies and techniques necessary to ensure sound corporate governance practices. Some such strategies and techniques are found in several papers issued by the Basel Committee on Banking Supervision.13

The Basel Committee on Banking Supervision has issued papers on several topics such as principles for the management of interest rate risk (September 1997), framework for internal control systems in banking organizations (September 1998), enhancing bank transparency (September 1998) and principles for the management of credit risk (July 1999). Taken together, these documents have highlighted some strategies and techniques which are listed below:14

- Corporations should cultivate values, develop codes of conduct and ethical behaviour and other standards of appropriate practices and put in place the system of governance with a view to ensuring their compliance.

- A corporate strategy, appropriate and well-articulated, should be framed against which the success or otherwise of a business enterprise and the contribution of individual players can be measured.

- Well-defined apportionment of responsibilities and assignment of decision making authorities, also specifying the hierarchy of required approvals from the level of employees to the board of directors.

- Setting up a system to facilitate interaction and to ensure cooperation among senior management, the board of directors, and the auditors.

- Establishing strong internal control systems, with both internal and external audit functions factored into it, risk management functions, which should be independent from business lines, and other checks and balances.

- Ensuring a system monitoring of risk exposures where conflicts of interest are likely to arise including business relationships with borrowers connected to senior management, large shareholders, or key decision-makers within the firm (e.g., traders).

- Instituting a scheme of financial and managerial incentives to act as a fillip to senior management, business line management and employees. These can be offered in the form of compensation, promotion and other means of recognition.

- Ensuring the required information flows internally and to the public at large.

BENEFITS TO SOCIETY

Corporate governance brings to the society immensurable benefits. These benefits are as follows:

- A strong and vibrant system of corporate governance can be a boon to society. Even in developing countries, where stocks of most firms are not actively traded on stock exchanges, adopting standards for transparency in dealing with investors and creditors is a major benefit to all stakeholders. Besides, it helps to prevent systemic banking crises.

- Research has proved that in countries where strong corporate governance practices prevail, the system offers protections for minority shareholders and has led to large and highly liquid capital markets. Countries whose laws are based on not so mature legal traditions and on weak regulatory systems tend to evolve into a system in which most companies are controlled by dominant investors rather than a widely dispersed ownership structure. Hence, for countries that are trying to attract investors—whether domestic or foreign—corporate governance matters a great deal in getting the required funds out of potential investors.

- It has been pointed out by many economists and management experts that competition in product markets as well as factor markets, especially for capital, act as constraints on unacceptable corporate behaviour. As a result, it promotes good corporate governance. In many developing countries, competition in products or goods markets is quite limited, especially where barriers exist. These ground realities further emphasize the importance of adopting the best possible corporate governance systems in countries where the market system is weak as in many developing countries, or yet to take proper shape as in many emerging economies. For instance, several Indian corporations that seek billions of dollars of foreign investments are prompted to put in their best corporate behaviour for that purpose.

- Corporate governance is also an effective instrument for combating corruption. In many developing societies this is a very tough subject to deal with, since the tradition is very much ingrained in the system and could arouse political sensitivities and cause potential legal action. By following ethical and legal practices as envisaged by good governance, a serious attempt can be made to root out corruption and malfeasance.

- Better corporate governance practices and procedures can bring about an improved management of the firm, especially in areas such as setting company strategy. Better corporate governance would also ensure that mergers and acquisitions are undertaken for strategic business reasons rather than for flimsy causes and that corporations’ compensation systems are made to reflect the performance of individual players.

- Good corporate governance also would bring about improvements in management structure and systems. In many developing countries, there has been a tradition of involving the promoters directly in the management of the firms they helped to promote. For example, throughout Latin America and parts of Asia, including India, family business groups have been dominating business enterprises. However, this is now changing as a result of globalization, following the World Trade Organization’s liberalization rules, and the increasing integration of regional markets. Nowadays, firms in these countries are increasingly adopting modern management strategies, techniques and financial accounting systems. All of these inevitably lead to delegation of authority, paying increased attention to HR policies and use of modern management information systems, instead of the erstwhile centralized decision making structures.

BENEFITS TO CORPORATION

Good corporate governance secures an effective and efficient operation of a company in the interest of all stake-holders. It provides assurance that management is acting in the best interest of the corporation; thereby contributing to business prosperity through openness in disclosures and accountability. While there is only limited evidence to link business success to good corporate governance, good governance enhances the prospect for profitability. The key contributions of good corporate governance to a corporation include the following:

Creation and Enhancement of a Corporation’s Competitive Advantage

Competitive advantage grows naturally when a corporation or its services facilitate the creation of value for its buyers. Creating competitive advantage requires both the vision to innovate and the strategy to manage the process of delivering value. An effective board should be one that is able to craft strategies that fit the business environment of the corporation, is flexible to accommodate opportunities and threats, and to compete for the future. Corporations that develop their strategies by involving all levels of employees create widespread commitment to make the strategies succeed. Practical examples of strategies that create value to corporations are sales and marketing strategies, customer base and branding strategies. Coca Cola projects American values to its customers worldwide. Sony is reputed for the invention of new products. Johnson & Johnson and Procter & Gamble are world renowned as the largest manufacturers of quality personal hygiene products.

Enabling a Corporation Perform Efficiently by Preventing Fraud and Malpractices

The code of best practice—policies and procedures governing the behaviour of individuals of a corporation—form part of corporate governance. This enables a corporation to compete more efficiently in the business environment and prevents fraud and malpractices that destroy business from inside. Failure in management of best practice within a corporation has led to crises in many instances. The Japanese banks which made loans to property developers that created the bubble economy in the early 1990s, the foreign banks which granted loans to State-owned enterprises that became insolvent after the Asian financial crisis in 1997, and the demise of Barings are examples of managements not governing the behaviour of individuals in the corporation, leading to their downfall.

Providing Protection to Shareholders’ Interest

Corporate governance is a set of rules that focuses on transparency of information and management accountability. It imposes fiduciary duty on management to act in the best interests of all shareholders and properly disclose operations of the corporation. This is particularly important when ownership and management of an enterprise are in different hands, as in these corporations.

Enhancing the Valuation of an Enterprise

Improved management accountability and operational transparency fulfil investors’ expectations and enhance the confidence on management and corporations, increasing the value of these corporations.

Ensuring Compliance of Laws and Regulations

With the development of capital markets and increasing investment by institutional shareholders and individuals in corporations that are not controlled by particular shareholders, jurisdictions around the world have been developing comprehensive regulatory frameworks to protect investors. More rules and regulations addressing corporate governance and compliance have been and will be released. Compliance has become a key agenda in establishing good corporate governance. After all, corporate governance ensures the long-term survival of a corporation.

Contemporary Corporate Governance Situation

In the original concept of the company, the basis of corporate governance was shareholder democracy. Shareholders were relatively few and close enough to the board of directors to exercise a degree of control. Indeed in millions of smaller, tightly owned companies around the world, that is still the situation today.

But for major corporations, particularly those that have their shares listed on a stock exchange, the governance situation has practically changed. In many countries, the shares of public companies are now held by diverse shareholders—some by private individuals, some by institutional investors such as banks, pension funds and insurance companies, and some by other companies, who might have business relationships with the company. Ownership structures of major public companies around the world these days are often complex. The first step in understanding the reality of corporate governance in a given company is to understand the ownership structure and, hence, the potential to exercise power and influence over that company.

In the past, most institutional investors ignored their rights as shareholders, preferring to sell their shares rather than getting involved in challenging corporate performance. However, a trend in recent years has been for some institutional investors, particularly in the United States, Great Britain and Australia, to become proactive, calling for boards to produce better corporate performance, questioning directors’ remuneration, and calling for greater transparency on company finances and for more accountability from directors. Indeed, one US institutional investor, CalPERS (the Californian Public Employees Retirement System), has produced corporate governance guidelines for companies in France, Germany, Japan and the United States.

Growing Awareness and Societal Responses

The growing awareness of corporate governance around the world has been reflected in a plethora of official reports on the subject. These include the American Law Institute Report (1992), the Cadbury (1992), Greenbury (1995) and Hampel (1998) reports from the United Kingdom, the Hilmer report (1993) in Australia, the Vienot report (1995) in France, the King report (1995) from South Africa, the OECD report in 1998, as well as studies in Hong Kong, Singapore, Malaysia and elsewhere. In India, the corporate governance code was first laid out by the CII in the wake of interest generated by the Cadbury Committee report, followed by an in-depth study made by the Associated Chamber of Commerce (ASSOCHAM) and the SEBI. SEBI appointed the Kumar Mangalam Birla Committee and adopted its report in mid-2000. The Reserve Bank of India (RBI) also constituted its own committee to study problems and issues relating to corporate governance from the perspective of the banking sector. Based on the inputs from these committees, the Department of Company Affairs amended the Companies Act in December 2000 to include corporate governance provisions, which became applicable to all Indian companies effective from 1 April 2001.

Many of the official reports provide a code of best practices in corporate governance, detailing expectations on matters such as board structure, audit and audit committees, transparency in financial accounting and director accountability. Some institutional investors, particularly in the United States have also called for codes of corporate governance practices; the best known being the CalPERS’ Global Principles of Corporate Governance. Increasingly, to obtain access to international equity finance, companies around the world have to respond to the corporate governance requirements of these codes.

Meanwhile the debate on companies’ responsibilities to other stakeholders, other than their own shareholders, has been increasing in the United States and the United Kingdom; the Royal Society of Arts’ (RSA) Inquiry in the United Kingdom produced a study called ‘Tomorrow’s Company’ (1995), which suggested responsibilities to a wider range of stakeholders.

Further, most major companies now operate through group structures of wholly owned subsidiary companies, partly owned subsidiaries in which other external parties have a minority equity interest and associated companies in which the holding company has a significant, but not dominant holding. In addition, the globalization of business dealings has meant that major companies frequently engage in a variety of joint venture and other strategic alliances with other companies. The second step in understanding the reality of corporate governance in a given company is to understand the network of ownership throughout the group, identifying minority interests in group companies and partner interests in joint venture companies.

Other reasons for the growing concern about corporate governance include changing societal expectations about the social responsibility of private sector companies, the attention being paid to more participatory political systems at national government level and the potential of global communications and information technology to spread ideas and to provide information on companies. The past decade has also seen a massive increase in academic research on corporate governance. At the heart of the exercise of governance over companies is the governing body, typically called the board of directors. It is vital to appreciate the role of the board.

INDIAN MODEL OF CORPORATE GOVERNANCE

The Indian corporations are governed by the Companies Act of 1956 that follows more or less the UK model. The pattern of private companies is mostly that of a business concern closely held or dominated by a founder, his or her family and associates. Available literature on corporate governance and the way companies are structured and run indicate that India shares many features of the German/Japanese model, but recent recommendations of various committees and consequent legislative measures are driving the country to adopt increasingly the Anglo-American model. In terms of the legislative mechanisms, Indian government and industry constituted three committees to study corporate governance practices in the country and suggested measures for improvement based on what was globally recognized as ‘best practice’. Significantly, most of the recommendations of the three committees—the SEBI-appointed Kumar Mangalam Birla Committee (2000), the Government-appointed Naresh Chandra Committee (2003) and the SEBI’s Narayana Murthy Committee (2003) are remarkably similar to those of England’s Cadbury Committee and America’s Sarbanes-Oxley Act, in terms of their approaches and recommendations.

The thrust of the legislative reforms suggested by these committees and subsequent legislative actions adopted centre around the strengthening of external governance mechanisms. This would call for greater transparency of company accounts and their certification by independent auditors. Investors would have access to these transparent accounts, as envisaged the Anglo-American model. Investors continuing to remain in the company or quitting it will depend on the availability of accurate and reliable information. ‘Institutional reforms, including a strengthening of oversight committees and the development of a serious fraud office, are further evidence of the drive to seek external monitoring of corporate affairs’. With regard to reforms in internal mechanisms as in the case of board of directors it was recommended that non-executive directors should be given greater role, while checking the growth of non-executive directors, as seen in the Anglo-American practice.15

Further, experts point out that India has adopted the key tenets of the Anglo-American external and internal control mechanisms, in the wake of economic liberalization and its integration into the global economy. In the sphere of legislative framework, for instance, Indian government and regulators have been following more or less the recommendations of English and American committees on corporate governance. Moreover, a small number of high-profile Indian companies have adopted these recommendations on their own, mainly with a view to approaching international markets, the Anglo-American protocols on corporate governance.16 Thus corporate governance developments in India in recent years show a paradigm shift from the German/Japanese model to the Anglo-American model.

There are differences between the three models of corporate governance. The actual practices adopted by companies also vary. Ideas and practices of corporate governance are evolving fast around the globe. There is no preferred model of corporate governance.

In the Anglo-American model, all directors participate in a single board, comprising both executive and non-executive directors, in varying proportions. In the German model, there are two boards, of which the upper board supervises the executive board on behalf of stakeholders, and is societal-oriented. In this model, though the shareholders own the company, they do not entirely dictate the governance mechanism. They elect 50 per cent of the upper board, while the other 50 per cent is appointed by labour unions, giving employees a share in the governance of the company. In the Japanese model, shareholders and the main lending bank together appoint the president and the board of directors. The main bank has a substantial stake in the equity capital of the company. Indeed, given the entrance of high-calibre directors with relevant experience, appropriate board leadership and a shared vision for the company’s future, each of the models can prove effective, provided they are consistent with the overall corporate governance infrastructure in that country.

These various governance systems form a package of overall corporate control in each company law jurisdiction. It is vital to see the package as a whole. There has to be an integrated harmony between state legislation and regulatory infrastructure, stock market regulation and corporate self-regulation.17

WHAT IS ‘GOOD’ CORPORATE GOVERNANCE?

Recently, the terms ‘governance’ and ‘good governance’ are being increasingly used in development literature. Bad governance is being recognized now as one of the root causes of corrupt practices in our societies. Major donors, institutional investors, and international financial institutions provide their aid and loans on the condition that reforms that ensure ‘good governance’ is put in place by the recipient nations. As with nations, corporations too are expected to provide good governance to benefit all its stakeholders. At the same time, good corporations are not born, but are made by the combined efforts of all stakeholders, which include shareholders, board of directors, employees, customers, dealers, government and the society at large. Law and regulation alone cannot bring about changes in corporations and make them behave better to benefit all concerned. Directors and management, as goaded by stakeholders and inspired by societal values, have a very important role to play. The company and its officers, who, inter alia, include the board of directors and the officials, especially the senior management, should strictly follow a code of conduct, which should have the following desiderata:

Obligation to Society

A corporation is a creation of law as an association of persons forming part of the society in which it operates. Its activities are bound to impact the society as the society’s values would have an impact on the corporation. Therefore, they have mutual rights and obligations to discharge for the benefit of each other.

- National Interest: A company and its management should be committed in all their actions to ensure that all their activities are beneficial to the development of the countries in which they operate.

- Political Non-alignment: A company should be committed to supporting a democratic constitution and should not offer its funds to any political party or campaign.

- Legal Compliances: The company should abide by the laws of the country in which it operates. It should abide by the tax laws of the nation and should pay all taxes imposed by the government as and when they become applicable.

- Rule of Law: Fair, legal frameworks that are enforced impartially are very important for good governance. An impartial judiciary is an essential requisite for good governance.

- Honest and Ethical Conduct: Every officer of the company should deal on behalf of the company with professionalism, honesty, commitment and sincerity as well as high moral and ethical standards.

- Corporate Citizenship: A corporation should be committed to be a good corporate citizen not only in compliance with all relevant laws and regulations, but also by actively assisting in the improvement of the quality of life of the people in the communities in which it operates with the objective of making them self-reliant and enjoy a better quality of life.

Such social commitment consists of initiating and supporting community initiatives in the field of public health and family welfare, water management, vocational training, education and literacy and encourages application of modern scientific and managerial techniques and expertise. The company should review its policy in this respect periodically in consonance with national and regional priorities. The company should strive to incorporate them as an integral part of its business plan and not treat them as optional or something to be dispensed with when inconvenient. It should encourage volunteering amongst its employees and help them to work in the communities. The company should develop social accounting systems and carry out social audit of its operations towards the community, employees and shareholders.

- Ethical Behaviour: Corporations have a responsibility to set exemplary standards of ethical behaviour, both internally within the organization, as well as in their external relationships. Unethical behaviour corrupts organizational culture and undermines stakeholder value. The board of directors has a great moral responsibility to ensure that the organization does not derail from an upright path to make short-term gains.

- Social Concerns: Corporations exist beyond the time of their founders, and have to set an example to their employees and shareholders. The company should not only think about its shareholders but also think about its stakeholders and their benefit. A corporation should not give undue importance to shareholders at the cost of small investors. They should treat all of them equally and equitably. The company should have concerns towards the society. It can help the needy people and show its concern by not polluting the water, air and land. The waste disposal should not affect any human or other living creatures.

- Corporate Social Responsibility: Accountability to stakeholders is a continuing topic of divergent views in corporate governance debates. In line with developing an integrated model of governance for an ideal corporate, the emphasis should be laid on corporate social responsiveness and ethical business practices. These are not only the first small steps for better governance, but also the promise of a more transparent and internationally respected corporation of the future.

- Environment-Friendliness: Corporations tend to be of an intervening, altering and transforming nature. For corporations engaged in commodity manufacturing, profit comes from converting raw materials into saleable products and vendible commodities. Metals from the ground are converted into consumer durables. Trees are converted into boards, houses, and furniture and paper products. Oil is converted into energy. In all such activities, a piece of nature is taken from where it belongs and processed into a new form. So companies have a moral responsibility to save and protect the environment. All the pollution standards have to be followed meticulously and organizations should develop a culture having more concern towards the environment.

- Health, Safety and Working Environment: A company should be able to provide a safe and healthy working environment and comply in the conduct of its business affairs with all regulations regarding the preservation of the environment of the territory it operates in. It should be committed to prevent the wasteful use of natural resources and minimize the hazardous impact of the development, production, use and disposal of any of its products and services in the ecological environment.

- Competition: A company should support the establishment of a competitive, open market economy in the country. It should also cooperate in efforts to promote the liberalization of trade by a country. It should not resort to unethical advertistments and practices in order to sell its products.

- Trusteeship: The board of directors has the responsibility to act as trustees to protect the rights and interests of the shareholders as well as the company’s other stakeholders. They are duty bound to uphold the concept of equity. They have to ensure that the rights of all shareholders, large or small, foreign or local, majority or minority, are equally protected

- Accountability: Accountability is a key requirement of good governance. Government institutions as well as private sector and civil society organizations must be accountable to the public and to their institutional stakeholders. In general, an organization or an institution is accountable to those who will be affected by its decisions or actions.18

- Effectiveness and Efficiency: Corporations must concentrate on producing results that meet the needs of society while making the best and sustainable use of resources.

- Timely Responsiveness: Good governance requires that institutions and processes try to serve all stakeholders within a reasonable timeframe. They should also address the concerns of all stakeholders and the society at large.

- Corporations Should Uphold the Fair Name of the Country: When companies export their products or services, they should ensure that these are qualitatively good and are delivered on time. They have to ensure that the nation’s reputation is not sullied abroad during their deals, either as exporters or importers. They have to maintain the quality of their products, which should then become the brand ambassadors for the country.

OBLIGATION TO INVESTORS

That the investors, as shareholders and providers of capital, are of paramount importance to a corporation is such an accepted fact that it need not be overstressed here.

- Towards Shareholders: A company should put in all possible efforts to enhance shareholder value and comply with laws that govern shareholder’s rights. Information should be disclosed to shareholders about all aspects of the company’s business in accordance with regulations.

- Informed Shareholder Participation: A related issue of equal importance is the need to bring about greater levels of informed attendance and meaningful participation by shareholders in matters relating to their companies without, however, such freedom being abused to interfere with management decision. An ideal corporate should address this issue and relate it to more meaningful and transparent accounting and reporting.

- Transparency: All decisions should be taken and enforced in an open manner. All rules and regulations must be followed. Efforts should be taken to ensure that information is freely available to those who are affected by decisions and their enforcement.

- Financial Reporting and Records: A company should prepare and maintain accounts of its business affairs fairly and accurately in accordance with the accounting and financial reporting standards, and laws and regulations of the country in which the company conducts its business affairs.

Likewise, internal accounting and audit procedures shall fairly and accurately reflect all of the company’s business transactions and disposition of assets. All required information shall be accessible to the company’s auditors, non-executive and independent directors on the board and other authorized parties and government agencies. There shall be no wilful omissions of any transaction from the books and records, no advance income recognition and no hidden bank account and funds.

Such wilful material misrepresentation of and/or misinformation on the financial accounts and reports shall be regarded as a violation of the firm’s ethical conduct and invite appropriate civil or criminal action under the relevant laws of the land.

OBLIGATION TO EMPLOYEES

For too long, corporations in free societies had been adopting a ‘hire and fire’ policy in employment of men and women in their work places and hardly treated them humanely taking advantage of the fact that workers had a commodity, namely labour that was highly perishable with little bargaining power. But in the context of enhanced awareness of better governance practices, managements should realize that they have their obligations towards their workers too.

- Fair Employment Practices: An ideal corporate should commit itself to fair employment practices, and should have a policy against all forms of illegal discrimination. By providing equal access and fair treatment to all employees on the basis of merit, the success of the company will be improved while enhancing the progress of individuals and communities. The applicable labour and employment laws should be followed scrupulously wherever they operate. That includes observing those laws that pertain to freedom of association, privacy, and recognition of the right to engage in collective bargaining, the prohibition of forced, compulsory and child labour, and also laws that pertain to the elimination of any improper employment discrimination.

- Equal Opportunities Employer: A company should provide equal opportunities to all its employees and all qualified applicants for employment without regard to their race, caste, religion, colour, ancestry, marital status, sex, age, nationality, disability and veteran status. Its employees should be treated with dignity and in accordance with a policy to maintain a conducive work environment free of harassment, whether physical, verbal or psychological. Employee policies and practices should be administered in a manner that ensures that in all matters equal opportunity is provided to those eligible and the decisions are based on merit.

- Encouraging Whistle Blowing: It is generally felt that if whistle-blower concerns had been addressed some of the recent disasters could have been avoided, and that in order to prevent future misconduct, whistle-blowers should be encouraged to come forward. So an ideal corporate is one that deals pro-actively with whistle-blowers making sure that employees have comfortable reporting channels and the confidence that they will be protected from any form of retribution. Such an approach will enhance the company’s chances to become aware of, and to appropriately deal with a concern before an illegal act has been committed, rather than after the damage has been done. If reporting is delayed, the company’s reputation can be seriously harmed and it can face a serious risk of prosecution with all its disastrous consequences. An ideal ‘whistle-blower policy’ would mean

- Personnel who witness an unethical or improper practice (not necessarily a violation of law) shall be able to approach the CEO or the Audit Committee without necessarily informing their supervisors.

- The company shall take measures to ensure that this right of access is communicated to all employees through means of internal circulars, etc. The employment and other personnel policies of the company should contain provisions protecting ‘whistle-blowers’ from unfair termination and other prejudicial employment practices.

- The appointment, removal and terms of remuneration of the chief internal auditor shall be subject to review by the audit committee.

- Humane Treatment: Now corporations are viewed like humans and a similar kind of behaviour is expected of them. Companies should treat their employees as their first customers and above all as human. They have to meet the basic needs of all employees in the organization. There should be a friendly, healthy and competitive environment for the workers to prove their ability.

- Participation: Participation by both men and women is the cornerstone of good governance. Participation could be either direct or through legitimate intermediate institutions or representatives. Participation needs to be informed and organized.18

- Empowerment: Empowerment is an essential concomitant of any company’s principle of governance which stresses that management must have the freedom to drive the enterprise forward. Empowerment is a process of actualizing the potential of its employees. Empowerment unleashes creativity and innovation throughout the organization by truly vesting decision making powers at the most appropriate levels in the organizational hierarchy.

- Equity and Inclusiveness: A corporation is a miniature of a society whose well-being depends on ensuring that all its employees feel that they have a stake in it and do not feel excluded from the mainstream. This requires all groups, particularly the most vulnerable, to have opportunities to improve or maintain their well-being.

- Participative and Collaborative Environment: There should not be any form of human exploitation in the company. There should be equal opportunities for all levels of management in any decision making. The management should cultivate the culture where employees should feel they are secure and are being well taken care of. Collaborative environment brings peace and harmony between the working community and the management, which in turn, brings higher productivity, higher profits and higher market share.

OBLIGATION TO CUSTOMERS

A corporation’s existence cannot be justified without it being useful to its customers. Its success in the marketplace, its profitability and it being beneficial to its shareholders by paying dividends depends entirely on how it builds and maintains fruitful relationships with its customers.