When one door closes another door opens; but we often look so long and so regretfully upon the closed door that we do not see the ones which open for us. | ||

| --Alexander Graham Bell | ||

In a market characterized by accelerating complexity and increasing customer expectations, moving along the Continuum from idea to market unimpeded is like driving through downtown Manhattan without ever encountering a red light—it never happens. Projects always take longer than expected and cost more than planned, and the development, marketing, and sales teams all periodically loose momentum and motivation. On top of that, the economy is like the flight deck of an aircraft carrier in rough seas, in that a pilot attempting to land a jet can never be quite sure if it will be a soft landing or a spine-jolting slap.

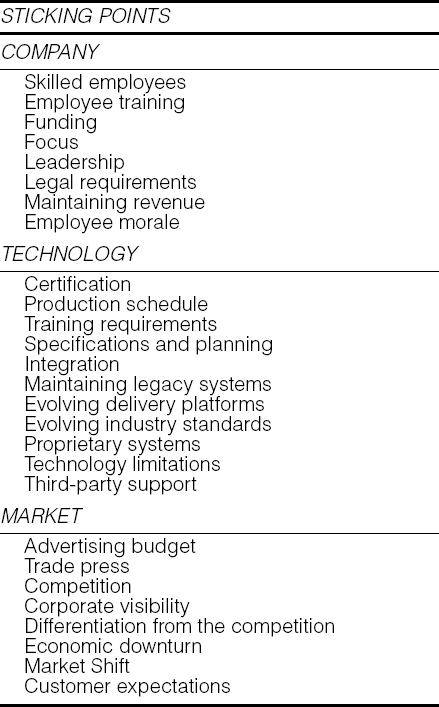

Getting stuck at various points along the Continuum is simply a fact of life. In this regard, a CEO is like a plumber, in that at least part of the job involves locating bottlenecks—structural, process, or organic—in what should be a smoothly operating system. Although every company's problems are different, they tend to cluster in three areas: the underlying technology, the structure and internal functioning of the company, and the capricious marketplace. Figure 5.1 lists the most common sticking points in each of these three areas.

Product development becomes a sticking point for any number of reasons. Furthermore, despite a business plan and research into the technological requirements, sticking points usually become apparent only after the transformation of an idea into a marketable product has begun in earnest. In this context, sticking does not necessarily mean hitting an impasse, but movement from one phase of the Continuum to the next may simply take more time than the organization anticipated or can afford in the short term. Consider that at the height of the dotCom boom, successfully funded companies evolved new generations of Web-based business innovations every few months. In this period of Internet time, laggards were left behind, scratching for the crumbs from the venture capital firms.

Sometimes getting stuck in the process of transforming a seemingly fantastic idea to a demonstrable prototype happens because the infrastructure of the supporting technologies is inadequate. In other cases, components and other technologies may be fully developed but not affordable in terms of capital expenditure or R&D resources.

Typical internal problems that can impede the process of coming to market are inept leadership and a shortage of skilled, motivated employees. These intrinsic components of a business process are usually more significant than any technology in the rate and quality of progress made along the Continuum.

Consider on one extreme how dissatisfied employees can strike for better compensation and improved working conditions. Less obvious, but just as devastating are low employee morale and a lack of willingness of employees to give their full attention to their work. This may be due to the nature of the work—for example, building missiles for a defense contractor that will sell them to third-world countries, which may be difficult for some engineers and technicians to get excited about. More often, however, the fault lies in the corporate leadership.

The situation is like having a professional basketball team saddled with a retired high school coach. Because the coach lacks relevant experience and the energy level to lead a pro team, the players either will not gel into a team or they will do so in their own terms. That is, they will elect their own leader and define their own goals to suit their best interests, which may be at odds with those of the team owner, the league, and the fans.

Conversely, a charismatic, energetic, and intelligent coach can recognize and bring out the latent talent in otherwise average players so that they will perform up to their potential. In business, a great leader can similarly create an environment and the incentives to bring out the best in each employee while achieving the goals of the company. Often, as in sports, bringing in a new leadership team can take a stuck company to the forefront of its industry.

A company can also lose momentum because resources have to be diverted from core technology developments to deal with legacy systems, training, and customer support, which can leave it with insufficient resources to move forward with R&D. When there is an existing customer base that is dependent on a previous generation of a company's technology, it is usually impossible to simply ignore the old customers, if only because they represent the most likely source of future revenue. This pattern is perhaps most obvious in the automobile industry, where companies groom customers to want future models by making certain that they are happy with their current car. Toyota takes care of customers who purchase a Corolla to maintain a positive brand image and ensure that when they buy their next car, it will likely be the higher-priced Camry.

Even with the best internal processes in place, the forward momentum of a product introduced into the market is often at the mercy of external factors, such as the prevailing economic winds. A product may fail because of general customer rejection of an entire market, such as occurred in the worldwide technology slowdown of 2001. The progress of several promising technologies, such as wireless access to the Web, was put on temporary hold because of consolidation in the industry, rethinking of standards, and a general drop in consumer spending.

Bad press (deserved or not), an insufficient advertising budget, or strong competition can also stymie a product's forward momentum in the marketplace. For example, a company may lack a Web site that showcases the benefits and features of a product for prospective customers. On the technical front, movement by industry leaders can spell disaster for smaller companies that have invested heavily in R&D toward achieving industry standards. For example, the short-range wireless standard, Bluetooth, backed by over 2000 vendors over the past several years, is in trouble. Microsoft and other companies that once backed Bluetooth announced products compatible with the increasingly common Wi-Fi or 802.11b wireless standard.

To illustrate the challenges associated with getting unstuck, consider the following scenario of a beleaguered high-tech company that experienced seemingly continuous challenges internally, technologically, and in the marketplace. Despite these challenges, the CEO and management team were able to generate enough momentum to achieve short-term profitability.

In addition to an opposable thumb, the trait that differentiates the human species from lower life forms is its ability to recognize, understand, and respond to speech. Not surprisingly, the public consciousness, guided by science fiction visionaries from Isaac Asimov to Arthur C. Clarke, judges the intelligence of any life form—including other humans—in terms of speaking ability. However, despite tales of robots and other machines capable of conversing with their human masters, as in Asimov's I-ROBOT series in the 1950s and HAL in Clarke's 2001: A Space Odyssey, which debuted two decades later, a machine's ability to speak in response to human speech has yet to be realized. The first step in this process will be the machine's ability to understand speech.

The first computer-based speech-recognition systems were developed in the 1950s, using analog computer hardware. Analog systems, which predate the currently popular digital computer architecture, were particularly suited for recognizing the patterns of speech because speech is an analog signal. However, because digital computers could be used for the military purposes of encrypting and decrypting messages before and during World War II, companies backing digital technology received the lion's share of funding from the German and U.S. governments. As a result, analog computing and the scientists who understood the applications of the technology, including analog speech recognition, were put on the fast track of an evolutionary dead end.

Speech recognition reappeared as a commercial product for microcomputers in the early 1980s. Part of the delay in replicating analog speech-recognition techniques in the microcomputer was the inability of early desktop systems to process external analog signals such as speech. The first microcomputer-based speech-recognition systems relied on dedicated, outboard speech-specific computers. These computer peripherals converted analog speech signals into digital signals, which were converted to keystroke equivalents, and then fed to the host microcomputer.

Toward the end of the 1980s, affordable, discrete-word, small-vocabulary, speech-recognition cards and software were available for the IBM PC from COVOX and other companies, which provided an inexpensive means for experimenters to work with speech recognition. Later, audio input and output cards, such as SoundBlaster from Creative Labs, together with the PC's microcomputer were used to support speech-recognition software. Similarly, Apple tried unsuccessfully to integrate speech recognition and speech generation into its Macintosh operating system. The short-lived experiment failed because of recognition inaccuracies, vocabulary limited to only a few thousand words, and the stipulation that users speak into the system with unnatural pauses between each word. All of these requirements were counterintuitive and went against customer expectations of what speech recognition was all about. As a result, after only about a year on the market, Apple dropped built-in speech-recognition capabilities from the Macintosh operating system.

While the early speech-recognition systems provided limited capabilities for speech recognition, they were nowhere near what science fiction writers—and therefore the general public—considered speech-recognition machines. As in Apple's experiment with the Macintosh, early units worked with discrete words with pauses after each utterance and very limited vocabularies. Normal, continuous speech was simply impossible to deal with. Even so, there were a few areas where discrete recognition of up to a few thousand words was at least partially useful.

The early, albeit limited, successes of discrete speech recognition technology were in medical reporting in specialties such as pathology, radiology, and emergency medicine. Physicians in these specialties used a limited vocabulary to describe findings, making the job for the speech-recognition engine easier. The time it took to transcribe reports and send them to other physicians who needed the findings justified the attempt to use the new speech-recognition technology to try to speed things up. Except for handicapped users and a relatively small number of early adopters in niche areas such as medical reporting, speech recognition of individual words on the microcomputer remained a curiosity at best.

In 1995, Bryan's company was contracted by the CEO of a major speech-recognition development company to help in evaluating and marketing his speech-recognition-based electronic medical reporting systems. At that time, the CEO, who we will refer to as Frank, was in the process of getting his company unstuck from an extremely uncomfortable business situation. Most of the former upper-level management team was incarcerated or awaiting trial resulting from charges of fraud. The Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) and the company's stockholders were understandably upset that some of the previous managers had artificially inflated sales figures. In order to have a successful public offering, it was necessary to demonstrate several consecutive quarters of profitability. However, the orders counted as filled never materialized. Apparently, shipments of speech-recognition software to customers were actually routed to a warehouse for storage.

Frank, a seasoned turnaround specialist, was hired to make the company profitable, increase shareholder value, and then sell the company for a profit. From his appearance—short sleeves and Rolex—and cramped, unadorned office, it was clear to everyone that he meant business and that he kept a constant eye on the bottom line. Not only were the quarterly employee updates held in the company dining room, where the meals consisted of pizzas, but also visitors to the company were treated to either Burger King or Pizza Hut instead of the former gourmet catering.

From an internal, corporate perspective, Frank faced several formidable challenges. The company had been hemorrhaging personnel for several months from low morale. This corporate-wide attitude was understandable, given the turmoil caused by the acts of the previous management. In addition, the multiple rounds of financing needed to keep the company afloat prior to Frank's arrival had severely diluted the value of the stock options held by the original employees, including the senior research scientists. The original stock options no longer provided the significant incentive that would be needed to turn the company around. On top of that, employee morale dropped because one of Frank's first acts was to reduce operating expenses by firing what he considered deadwood—about a third of the employees.

An additional internal sticking point was that the company was actively engaged in several businesses—speech-enabled electronic medical records, system integration, general-purpose speech recognition, and PC hardware sales and support—all of which diluted progress in the speech-recognition arena. Resources that could have been focused on speech-recognition R&D had to be diverted to other areas. For example, there were hundreds of legacy medical-record-reporting systems that had to be kept running in accordance with maintenance contracts. Most important, fulfilling the maintenance agreements accounted for most of the company's day-to-day revenue stream.

Early on, it made sense for the company to enter the PC hardware business. The speech-enabled medical-reporting systems required a proprietary hardware card that had to be installed and tested by a speech-recognition technician. In addition, to make the purchase decision easier for hospitals and clinics, the company offered a total electronic medical record solution, placing it squarely in the PC hardware support business.

To add to the potential confusion, there were projects in progress that dealt with connecting the PCs configured as medical dictation systems to hospital systems, and these custom connections or interfaces required several weeks of on- and off-site work by integration specialists. The medical division of the company was also charged with maintaining the accuracy and integrity of a variety of medical databases. This work ensured that the reports generated by the speech-recognition system were medically correct and that online resources, such as the formulary—the list of drugs available for physicians to order—were up to date and accurate. Billing codes, a major reason that hospitals and managed care practices invested in these systems, were part of the databases and also had to be regularly updated.

From a technical perspective, the R&D division of the company was stuck as well. The "holy grail" of speech recognition—continuous speech recognition on a standard laptop or desktop PC—still seemed six months to a year away, and yet the word in the industry was that the competition was nearly there. Part of the technological challenge was that the R&D division had been dividing its energies among multiple areas. Legacy medical reporting systems that were based on proprietary hardware cards had to be migrated to a software-only solution that did not require the expensive, custom-made, plug-in cards.

In addition, the new speech-recognition engine, which had been under development for a year, was based on the new Windows operating system. This meant that existing installations had to be upgraded from DOS to Windows. However, since most of the PCs in service were physically incapable of running Windows, much less the new speech-recognition engine, PCs had to be upgraded to units with high-speed processors and as much RAM as the customer could afford. In addition, a liaison from R&D had to work with the documentation division in order to create online and print directions for how to set up and use the new systems.

The R&D department was also under extreme pressure to quickly develop a variety of speech-recognition tools to fit a variety of market niches. The department was tasked with creating a general-purpose speech-recognition system that was tightly integrated with Word, Excel, and other standard applications. For example, a user should be able to say "bold that" to change the format of a selected sentence or word from normal to bold.

The seemingly constant rollout of software taxed the efforts of the core development team, as well as those in support, training, documentation, and marketing. In addition, government contracts for specific applications of speech-recognition technology, from advanced medical-reporting systems to controlling tanks in battle through speech commands, had to be managed. Employees in the medical-reporting division also had to stay current with and actually drive changes to the standards associated with electronic medical records. For example, there were debates in the medical-reporting industry over the image format that should be used to send images from one PC to the next.

From an external market perspective, the company was stuck because of the general public's disinterest with discrete speech recognition. In addition, even in the niche area of medical reporting, the vast majority of physicians did not care for the speech-enabled reporting systems, and many used the system only when they were paid for the extra time it took to dictate a report using speech recognition. This attitude was a reflection of the time and energy investment required to become even partially competent with the systems.

Many physicians required class instruction and individual tutoring to attain proficiency, and even then most found it quicker to hit a key for a command instead of speaking the command. Even worse, if a word was misunderstood, then the correction process was even more arduous and time consuming. As a result, most physicians used some combination of keyboard commands and voice dictation in a talk-and-type interface. Faced with the prospect of impending competition from another company with a continuous speech-recognition system running on standard Windows hardware, Frank sought to attract additional funding to expand the marketing arm.

The key sticking point with marketing and one that Frank could not adequately address, was that in many respects the entire speech-recognition industry was a solution in search of need. Although there were a few key military applications for hands-busy, eyes-busy situations, the civilian market, which included the disabled and dyslexic, was not large enough and did not have deep enough pockets to yield sustainable revenues for the long term.

In addition, the state-of-the-art accuracy limit of one or two errors for every 10 words dictated, and the lack of any real demand for general-purpose speech recognition on the PC, had never been fully addressed. A telltale sign, and one that did not change during Bryan's three-year tenure as a consultant for the company, was that not one of the 120-plus employees used speech recognition in their daily work. Everyone in the company, without exception, preferred to use a keyboard and mouse when work had to get done. Besides, the cacophony that would have been created by a hundred cubicle workers talking to their PCs would have been deafening.

At first glance, it is easy to see why a proven turnaround artist like Frank could command a significant salary and stock options. In addition to walking into a company demoralized by corrupt management and having to fire dozens of employees, Frank had to set the tone for the organization by personal example. His focus was the bottom line, and he had to make certain that everyone knew what was expected of them. There was an unambiguous message that those who produced were welcome and would be rewarded for their contributions, and those who were not willing to work would be told to leave. It helped that Frank walked the walk and talked the talk. Although he was a little rough around the edges—a trait no doubt picked up from his decades of turning around companies in the heavy manufacturing industry—he was respected, and sometimes even feared, for his directness.

One by one, Frank addressed the technical, corporate, and market sticking points. For example, each division within the company was held responsible for its own return on the corporate investment. For this reason, the medical division, the major source of ongoing revenue, tried to distance itself from the PC hardware support business and encouraged customers to upgrade to the new Windows-based solutions. It also aggressively bid on and won several government requests for proposals (RFPs) for the development of a variety of speech-enabled clinical systems.

As part of his makeover strategy, Frank brought in new vice presidents of sales, marketing, and R&D, and shifted the long-term focus of the company from medicine to the general consumer market. Money was allocated for an expanded marketing campaign, and the company issued new stock options to increase employee morale and, by extension, productivity.

To move the technical development along, Frank gave the core technology group extra stock as an incentive to spend nights and weekends working on developing a general-purpose, continuous-speech solution as soon as possible. Frank, working with his management team and advisory board, helped focus the core developer activities on solutions that would make the largest impact on sales. This strategy worked so well that the company was one of the first to market with a general-purpose, large-vocabulary, speech-recognition product.

While getting the company unstuck, Frank also courted prospective buyers while the new marketing group focused on the press. Finally, after demonstrating that the company was in the black by showing several consecutive quarters of profitability, a buyer was found. After a few weeks of intense negotiations, the company changed hands. Like major league ball players with a winning season behind them, the employees saw that the reward for success was, unfortunately, to be traded away. Frank walked away with a handsome portfolio of stock options, and the new owners—a European company with visions of dominating every form of speech technology on the planet—had a viable technology and nationally recognizable consumer product. What's more, only weeks after the agreement, the new management secured a multimillion-dollar investment from a major software company and recouped their investment in speech-recognition technology overnight. The new company, which worked like the Borg in Star Trek, acquired and assimilated any and all speech-related companies that it could identify, including the major competitor of their new speech-recognition division.

Although the European conglomerate of speech-related software and services was apparently financially successful, the difference between employee life and morale before and after the takeover became apparent almost immediately. Instead of the usual quick quarterly update over pizza in the company cafeteria, the takeover celebration was a catered event, with lobster and all the extras. Unfortunately, not everyone under the white tent erected on the lawn for the special event would be employed the following week. Instead of Frank's direct manner and open-door policy, the new management team wore an air of European aristocracy, with double-breasted suits and tailored shirts for normal office attire. Employees and consultants no longer had access to management, unless summoned. Corporate culture went from startup to Fortune 500 overnight, and employees were expected to fall in line or fall out. Many employees left the company at the point of acquisition, though the brain trust stayed.

As part of the acquisition, the company moved to a larger building, where management occupied offices with windows and expansive views, and employees shared a central cubicle farm. Instead of Frank's walk-in-closet office, the new CEO's office was large enough to hold a miniature golf course. As employee attrition increased because of dissatisfaction with the company culture, the company retaliated by increasing the stock options for those who remained, but coupled the "gift" with expectations of longer work hours. The new corporate culture became one of endurance; those who could endure the company long enough to cash in on stock options won the game. Camaraderie and pulling toward a common goal took on increasingly less meaning.

Bryan's company terminated its relationship with the new speech company as part of an exodus of employees from the company. Within the next 18 months, as the stock experienced a roller coaster ride of valuation, there was word of possible impropriety in the way profits were being reported. Ironically, in a repeat of what had happened only five years earlier, management was accused of false reporting of sales in order to artificially inflate the price of the stock.

By the end of 2000, upper-level management was behind bars, the company was in Chapter 11, and the stockholders were pressing a class action suit against management. Those employees who held stock in the company were left holding paper of unknown future value. The entire speech-recognition industry was left in turmoil, and tens of thousands of customers were left stranded without support—a major problem for the speech-recognition companies remaining in the marketplace.

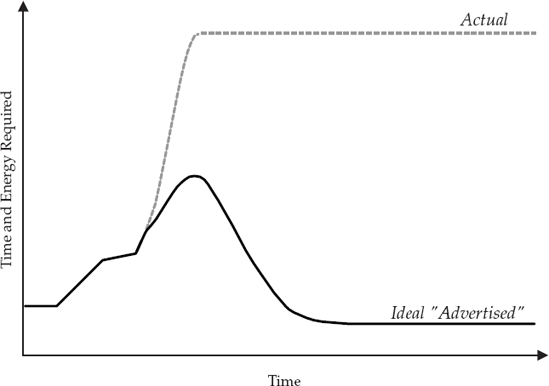

Today, the use of microcomputer-based speech-recognition software is still limited to a relatively small number of innovators, despite a tenfold drop in price since continuous speech recognition was first introduced a few years ago. With the exception of physically challenged workers, including those suffering from repetitive stress injury, the keyboard is simply an easier, more efficient, and more effective device for entering data. As illustrated in Figure 5.2, most users of voice recognition eventually find the return on investment to be negative, in that the effort needed to use a pure speech-recognition interface is not worth the hassle of learning, and the end result is less effective and more time consuming than using a keyboard and mouse alone. Because a combination of speech recognition and a keyboard-and-mouse interface seems to work best, most speech-recognition products accommodate multimodal use.

Despite lack of progress on the desktop, speech-recognition technology is making significant inroads in phone-based access to data, including data on the Web. However, regardless of the ultimate fate of the technology, the story of the speech-recognition company illustrates several points about getting unstuck. The case illustrates how given the proper leadership, it is possible to get unstuck from a seemingly hopeless situation. Conversely, poor leadership is the quickest way to become stuck. In this regard, the personality of the CEO, the chemistry among top-level management and workers, and the culture of the working environment are critical factors in establishing and maintaining progress in the corporate, technological, and marketing components of business.

The case also illustrates how success requires the CEO and other decision makers to communicate a clear, unambiguous vision articulated in concrete terms and reflected in their everyday activities. Getting unstuck is first about managing and understanding customer and employee needs and desires; overcoming technical and market hurdles are secondary.

Although every situation is different, the issues addressed by these axioms are common to most businesses. Depending on the particular business arrangement, other situations might call for identifying a development partner or licensing intellectual property in exchange for operating capital. What does not work is simply throwing money at a problem, as many failed dotCom enterprises have illustrated. If given the choice, most employees would not trade increased working hours and a more stressful work environment for a lobster dinner and the promise of an unknown reward at some later date.

The story of Frank's company illustrates that, unlike fairy tales, companies do not go on to live happily ever after. The remarkably influential Apple II, like the Volkswagen Beetle, has come and gone, replaced by better technology. Similarly, amid what appeared to be great strides in profitability and increased consumer awareness, management of the international speech-recognition company apparently repeated the deeds of their predecessors. Because of insufficient consumer demand, the new management team falsified millions in sales in order to inflate stock prices for personal gain and to stay in business.

They also structured the company in a way that is legal in Europe but illegal in America, a way that allowed them to license technology to holding companies that they themselves started. The holding companies took the voice-recognition company's seed money to get started selling voice-recognition technology, and then the parent company reported the licensing of its technology to its holding companies as income or profits. As a result, the entire microcomputer-based speech-recognition market was thrown into turmoil—a major issue for turnaround CEOs to solve in each of the acquired companies.

Even if the management of the speech-recognition company had stayed on the straight and narrow, it would have faced the major sticking point related to the limitations of the technology. Perhaps it was this realization that the demand for the technology was in decline that pressured management to falsify sales figures.

Although the technologic hurdle from discrete to continuous speech was formidable and costly to overcome, the next technological hurdle is even more formidable. What remains is to create a system that not only recognizes sounds and matches these sounds with commands or words, but that provides some sense of understanding of the sounds. Current systems are little more than lookup tables of sounds, words, and word frequency. The next logical evolutionary step is to provide a degree of artificial intelligence (AI) in the translation of spoken English or other language into text. In theory, doing so should negate the need to correct the one word out of ten or twenty translated words that is mistyped by current systems. The telltale sign that the technology has reached the Product Point is when companies that make speech-recognition software will actually use it internally.

For now, however, the major uses of speech recognition are associated with cellular and wired phone systems. Phone-based speech recognition is commonly used to provide speech-activated navigation commands for telephone users attempting to navigate through speech mail systems. The "say or press one" option is part of most telephone banking and charge card support routines.

The other, more pervasive but less publicized application of speech recognition in the phone system is the monitoring system established in the 1990s by the FBI. The mainframe-based system scours the nation's phone lines, at a rate of thousands of lines per second, searching for specific words, such as "bomb," "assassination," "President," and "kill." When one of the trigger words is detected, the FBI flags the phone line for follow-up action.

Frank's makeover of the speech-recognition company illustrates many of the potential sticking points in developing and then bringing a product to market that are listed in Figure 5.1. There are unlimited opportunities to lose momentum, sacrifice profitability, and succumb to the temptation to deviate from the central goal while chasing distractions. The specific sticking points illustrated by the voice-recognition company include numerous instances of internal process failure. The established process of recording and verifying sales was fundamentally flawed in that it prevented detection by those employees outside of top management.

Without a failsafe mechanism in place, management, through its mistakes, was able to lead employees and stockholders over a virtual cliff. It is also clear that the company suffered from a communications failure at every level. Amid the turmoil, employees did not know what was happening with the company or what was expected of them to improve the situation. Similarly, the board of directors apparently had no indication of wrongdoing and did not question the figures on which they based their recommendations.

The case also highlights how once self-motivated employees can become suddenly demoralized and disenfranchised because of inept leadership. The original management group confused the mission of the company and minimized the rewards employees could expect for their efforts. Even though employees were helping to make a change in society by providing tools to physicians and hand-disabled users, not simply making money for stockholders, the defocused mission and lack of a broader market for the technology played predominant roles in the initial downturn for the organization. Additionally, after the fraud was uncovered, most of the otherwise idealistic employees lost focus and productivity.

Finally, the case illustrates how external factors, from the SEC to customer behavior, can have a profound influence on the trajectory of a company. Obviously, the legal proceedings paralyzed corporate management, at least temporarily leaving employees directionless and unproductive. Perhaps most important, and at the root of the matter, customers for the original general-purpose voice-recognition products never materialized because of product usability limitations.

In addition to those specific sticking points, each point and period within the Continuum tends to be associated with certain types of sticky situations more than others. The generic descriptions for these stages and periods in the Continuum are described here.

Getting stuck at the very beginning of the process, when the business plan is being fleshed out and presentations are being made to colleagues, relatives, and anyone else who might be a source of funding or expertise is akin to having writer's block. The process of formulating a defendable business plan that can hold up to the scrutiny of others usually highlights the advantages of a new technology as well as multiple, unanswered issues that may not have been obvious before.

Of course, it is possible to fall upon an idea and even a prototype through serendipity. Researchers looking for something else stumbled upon vulcanized rubber, 3M Post-It™ Notes, and Teflon. A chemist attempting to make a super-strong adhesive, for example, developed the Post-It Note. The semisticky glue, when spread on small sheets of paper, turned out to have far greater value in the marketplace than any super adhesive. Similarly, a graduate student who was looking for a new coolant to use in refrigerators accidentally discovered Teflon. Teflon, one of the top-secret materials used in many military projects in World War II, is still the basis for a multimillion-dollar industry that extends from nonstick cookware to valves and military arms.

Although serendipity is always welcome, having an idea or even a product in hand is not sufficient to bring it to market. Getting stuck at Inception may involve failure to define a competitive advantage for the proposed or discovered product. The time, money, or other resource requirements may be out of line with the potential value of the product. As was the case with Nicolas Tesla, the inventor of several everyday AC devices, many inventors have held multiple jobs in order to pay for their research into building a better mousetrap.

A major potential stumbling block at Inception is dependence on supporting technologies that are not available or accessible. In the case of the speech-recognition software, continuous speech recognition required moving from DOS to Windows, which in turn required a more powerful PC than most potential customers owned. Fortunately, faster, more powerful PCs were only a few months away.

Depending on the market, competition can either spur development or stop it cold. The fact that several companies were working on continuous speech recognition did not impede Frank's determination to be the first to achieve the goal. There was worldwide competition from the other speech-recognition companies, and it was only a matter of time before one of them succeeded at bringing continuous speech recognition to market. As it turned out, one of the competitors was first to market with a continuous speech-recognition product.

However, if Frank's company had not been a close second, the company would have been out of the commercial speech-recognition business. The sticking point of getting from discrete to continuous speech recognition was not over the validity of the idea but rather the timeline; if achieving continuous recognition was a decade—not months—away, then Frank might have decided to halt development and seek to license the technology instead. However, in many instances, the best decision is to simply go with it, especially since so much of the data may be pure speculation and unknowable.

An achievable set of goal-oriented deadlines is just one factor that the formulation of a good business plan should highlight. Since the lack of a clear, realistic business plan with a sustainable financial model and defined marketing strategy can halt progress, input from technologists, experts in the field, and experienced investors can be key to getting unstuck.

Intellectual property issues can slow or halt progress at Inception, especially if patents and other legal instruments have to be filed before real development can begin in earnest. In general, technical limitations are much more easily addressed than are political and social objections to technology. For example, there will be intellectual property, political, legal, and social impediments to human cloning in the United States for years to come.

This phase along the path of transforming an idea into a viable product is normally the time of idealization and acquiring the mental momentum that will be needed to invest the time and energy to create a prototype. The developers in Frank's company, for example, were faced with the task of creating a continuous speech-recognition engine—something that was theoretically possible, but not yet demonstrated in a stable, commercial product.

However, the period of concept development can also be a time of self-doubt, especially with the realization of exactly how much energy and time will be involved simply to prove that the approach will work. This self-doubt may be deepened if the capital requirements are out of line with what could support a business.

Often the main sticking point at this phase of development is the prospect of dealing with a formidable project in a David-versus-Goliath confrontation. Getting unstuck from starting on what may seem to be an impossible task involves basic project-management techniques, such as dividing the project into manageable steps, and delegating components of the steps whenever appropriate. Establishing reporting and work structures to formalize the responsibilities of specific employees can also reduce the sense of chaos associated with a significant project.

The Technical Gateway, where the goal is to create a demonstrable prototype, is one of the major milestones of technical product development. It is also the point in development where the probable performance of the planned product in the marketplace may become obvious. For the first time, it may be possible to realistically compare the product under development with competing solutions in the marketplace, and thereby obtain a much better idea of the size of the likely return on the investment. An unfavorable likely return on investment is an obvious sticking point. For example, once a continuous speech-recognition engine had been developed, the developers and marketing staff of the speech-recognition company were able to project the time and resources it would take to commercialize the prototype.

In addition to providing a reality check, getting stuck at the Technical Gateway may demonstrate the development team's inability to define the functional specification clearly and completely enough for an early prototype to be built. Getting unstuck may require partnering with a company or hiring individuals with a proven track record of prototype development in the field, or assigning someone in the development group to research additional development options.

The period of prototype development is the time when uncertainty predominates, but this lack of certainty need not translate into stagnation. Sticking points include an inability to actually connect with the potential markets and customers identified in the business plan. Getting unstuck usually involves hiring at least part-time marketing and sales professionals. Many companies generate advertisements at this stage simply to gauge initial customer-response rates. A low response rate may suggest that the targeted market is inappropriate for the product, or perhaps that additional features may be required.

Although there usually is not a time when an infusion of additional capital would not be accepted, this period is typically capital intensive because significant funds may be required to create a demonstrable product. Regardless of the promise of the product, the groundwork for funding may be difficult to develop because of external limitations in the economy. Getting unstuck may involve hiring a research firm to resolve some of the uncertainty about the economy and locate additional sources of funding. For example, Frank's company applied for and received several government grants to spur development.

Getting stuck at the Product Point is unfortunately very common. One of the major causes is the composition of the management team, especially the CEO. Often, the original inventor with a technology focus does not change from an idea person to a market-oriented manager. When the inventor will not hand over control to an entrepreneurial CEO, the company usually falters. A technology-minded CEO may not be able to recognize the commercial applications for his product, and may be more concerned with deploying the technology that he worked so long to create.

A CEO without a customer focus at this point in product development will not be able to create a story for potential investors. The work-around for the wrong management team is to somehow convince the technologically savvy but entrepreneurally naive CEO that assuming another position in the company, such as chief scientist, exposes the company to lower risk. If the management team fix involves lower-level employees, then they can simply be replaced with more effective employees. For example, one of Frank's first acts was to establish a new management team that understood the focus of the new company was to use speech recognition to realize a profit for shareholders.

Once a demonstrable product has been created, the challenge is to refine the technology while keeping the customer's needs and wants in mind. However, it is not always possible to produce the rapid, incremental innovations required to better meet customer needs or reduce costs. Getting unstuck during the Clarification phase of product development may require strategic replacement of management so that the resulting body has more of a customer focus. For example, Frank replaced the vice president of R&D with a more market-minded manager, which seemed to be what was needed at the time to get the company moving.

Getting stuck in the Market Gateway is possible, though frustrating. Insufficient market share, improper positioning to maintain growth, and lack of resources to maintain an R&D effort—while resources are being consumed by creating product updates—are all possible pitfalls at the Market Gateway. A technology with a very limited life span, such as a tax program designed for a specific year, obviously limits the shelf life of the program. Similarly, competing technologies on the horizon can also break the momentum. Microsoft is famous for stalling the competition in their tracks by preemptively announcing a "killer product" that competes with the company's newly developed product. For example, Microsoft's preannouncement of its Xbox video console cut into PlayStation II sales. Getting unstuck can entail exploring and developing new technologies in order to maintain or gain market share.

In the speech-recognition company, getting stuck with undeliverable product and hiding this fact from investors was the genesis of the problems of the mid-1990s and again in 2000, which resulted in the incarceration of the management teams involved. The pitfall was ultimately consumer rejection of the technology.

Impediments to progress during Stabilization, when the technology is maturing, are usually due to public resistance or some internal event that leaves the company in disarray. Although there is typically an emergence of significant competition and perhaps minor enhancements to the underlying technology, this time is characterized by a market focus. Many genetically modified foods failed at this point in the Continuum.

Alleviating the political, legal, or attitudinal limitations at this phase of development may be much more formidable than overcoming economic limitations. For example, obtaining permission from the EPA to introduce GMFs for human consumption may take years and very deep pockets.

Getting stuck at Completion is associated with uncertainty about what should be done with product on the shelves. If the product is not viable in the marketplace, then at issue is whether the technology should be modified or left alone. For example, although speech recognition promised to increase ease of use of the computer for the average consumer, in its current incarnation, the technology has only served to increase the complexity of operating a computer.

If the product is in a maturing market, then keeping the momentum up may involve applying the product to new markets. With the speech-recognition software fully developed, for example, Frank's company was able to repackage the software and add enhancements so that it could be used by clinicians. The challenge is often balancing the need to keep momentum up with marketing and sales while investing resources in R&D for future products.

Getting stuck is not necessarily a bad thing. For a CEO tasked with creating a marketable perpetual motion machine, the sooner the development project is stuck, the sooner the developers can realize that aborting a hopeless project is the best decision. Even with less lofty product development and marketing goals, getting stuck can often point out that there may be a better way to achieve the desired results. Licensing a technology may be the quickest, most economical means of acquiring a particular technology, or of achieving a particular result. In Frank's case, his goal was to bring the company to profitability—not simply by meeting expectations but by defining new ones. From the perspective of the board of directors, how Frank reached that goal was irrelevant, as long as it was done legally.

There is no simple recipe for success based on identifying sticking points, but rather success depends on creativity, that is, thinking of new ways to solve old problems. The challenge of communications, for example, has plagued business since before the concept of business was formulated. Similarly, resolving the multitude of sticking points in the speech-recognition company called for creativity on Frank's part. Knowing that there will be challenges, and knowing that they can all be solved creatively, can help provide the CEO the means needed to deal with the never-ending barrage of challenges inherent in business.

Getting stuck at various points in bringing an idea to market is inevitable. The challenge is getting unstuck in a timely, economically feasible, and socially and politically correct way. This is where the leadership and visionary qualities of a CEO come into play. Given a CEO with the proper leadership qualities, including the ability to articulate and communicate an unambiguous vision in clear, concrete terms, it is possible for a company to get unstuck from seemingly hopeless situations. In the end, leadership is about motivating people, whether they are employees or potential customers and investors.

As the case history of the speech-recognition company illustrated, getting stuck—and unstuck—often involves the raveling and unraveling of product technology, corporate processes, and the market. The case also illustrates how the most significant issues, and the most difficult to fix, are people-related, especially those charged with defining the direction of the company. The personality and leadership qualities of the CEO, the chemistry between top-level administration and front-line employees, and the culture of the working environment are critical to maintaining momentum along the Continuum.