The better telescopes become, the more stars there will be. | ||

| --Gustave Flaubert | ||

Technology alone is not enough to guarantee the success of a product in the marketplace. Timing, the political and economic environment, the competition, and customer acceptance are also important. On the surface, assessing the customer acceptance factor seems straightforward. After all, despite the exponentially increasing rate of technologic evolution in the past few centuries, human behavior has not changed much since recorded history. Take status symbols, for example. We walk around with the modern equivalents of face paint and ceremonial weapons, and wear costumes imbued with supernatural powers. The police officer's uniform, attorney's custom suit, and physician's white coat and stethoscope are all instantly recognizable and, to varying degrees, respected.

When it comes to accepting new technologies, some groups of potential customers are more reluctant than others to change behavior even when new products require it. Resistance to change may simply be based on experience with products that fail to perform as promised, but it is usually a reaction to a combination of deep-seated personal beliefs and social issues.

As an illustration of the complex interaction between customers and new technologies, consider the technologic and social evolution of the stethoscope, the device physicians use to listen to a patient's heart and lungs. To many laypeople, the stethoscope is synonymous with medicine. For this reason, medical students, EMS professionals, and clinicians of all types often drape one over their necks just to visit the local Starbucks. However, the stethoscope, which virtually transformed Western medicine, is a relatively new invention, dating back to only 1816.

From antiquity to the beginning of the 19th century, clinicians listened to the chest (stethos in Greek) in the most direct way possible—by placing an ear directly against a patient's chest. However, there are a number of disadvantages to this approach. For one, it is difficult to place an ear directly over a specific area of the chest—over a heart valve, for example—without the clinician resorting to a number of contortions. There is also the unpleasant prospect of having to come into close contact with a bleeding, coughing patient (many physicians who treated tuberculosis or consumption in 17th- and 18th-century Europe succumbed to the disease). What's more, in prudish 18th-century Europe, when medicine was an all-male, deteriorating profession, and toxic mercury and bloodletting were in vogue for the treatment of nearly every malady, putting an ear to the breast of a young female patient to listen to her heart was simply taboo.

Although the nature and practice of Western medicine has fluctuated throughout the millennia, from the Hippocratic technique of tasting a patient's urine for the sweetness characteristic of diabetes mellitus to the open and public dissection of executed criminals in Leonardo da Vinci's time, medical practitioners in 18th-century Europe were ignorant of functional anatomy. Lacking any substantive knowledge of functional anatomy, they based medical diagnoses on externally visible signs and patient symptoms. A fever, a rash, or swelling, together with the patient's complaints regarding the frequency, duration, and intensity of pain or discomfort were the basis of most diagnoses. There were no lab tests, no concept of testing for hearing or vision, and no system for understanding the diseases of internal organs, such as the heart and lungs.

However, the world of Western medicine began to change in 1816, when the French physician René-Théophile-Hyacinthe Laennec needed to listen to the chest of a young woman to verify his presumptive diagnosis of heart disease, but could not do so because social restrictions prevented him from placing his ear against her naked breast. Determined to listen to her heart and lung sounds, in a flash of insight he rolled up a few sheets of paper into a tight tube, forming the first chest listening device. He put one end in his ear and the other on the woman's chest and was delighted to be able to hear the heart sounds—much louder and more distinctly than before.

After his discovery, he rushed to the lathe in his workshop and crafted the first real stethoscope, in the form of a hollow wooden tube. He spent the next two years investigating and documenting its use in the diagnosis of various lung and heart conditions. His book on the subject, published in 1819, served to inform other physicians not only how to construct their own stethoscopes, but how to use them in practice as well.

Laennec's invention began a revolution in the very nature of medical practice, shifting it to the objective measurement of phenomenon and placing much less emphasis on the patient's memory of heart symptoms, which tended to be poor. Because of this fundamental change, other physicians did not immediately embrace the stethoscope. However, within about a decade, the new, objective style of medicine had taken root, and a number of other physicians had developed their own improvements on Laennec's hollow wooden tube design. Although the dual-earpiece design was introduced in the 1830s, it did not become popular until the 1850s. The first instrument recognizable as a modern stethoscope—a pair of flexible rubber tubes connecting a set of earpieces to a metal chest piece—was developed in 1855. However, even though the design proved superior in usability and acoustics to other designs, it was not until 1866, when it was endorsed by Austin Flint, an outspoken physician of the time, that it became accepted and soon thereafter came into widespread use.

Today, most chest pieces (the metal, disk-shaped part that is placed on the patient's chest) have two sides, one open to the air and one covered with a thin plastic membrane. The open-ended side, called the bell, accentuates low-frequency sounds, like those of the normal heart. The side covered with a membrane filters out the low-frequencies, allowing high-frequency sounds, like the crackles generated by diseased lungs and the murmurs of abnormal hearts, to be more distinct. Since the introduction of the membrane chest piece around 1910, the stethoscope carried by the vast majority of clinicians has changed very little.

The major players in the stethoscope space are manufacturers such as 3M, Littmann, Tycos, and Welch Allyn. Models range from $20 to $350 to suit the budget—and image—of the user. Although there are some areas of medicine where a special stethoscope design is warranted, such as pediatrics, which requires a smaller diameter chest piece to localize sounds from the heart of a small child, a skilled cardiologist can make a diagnosis with the simplest, cheapest stethoscope. Masters at the stethoscope can use any of the dozens of standardized models available with equal facility, in part because they have a highly developed ability to recognize certain sounds, and because they can use the stethoscope like a sensitive radio receiver—tuning in to certain sounds and blocking out others. A good cardiologist can use the simplest bell chest piece to listen to high frequency sounds of heart murmurs by pulling the patient's skin taut to form a membrane over the chest piece, filtering out the lower frequency sounds just as a plastic membrane would.

Many physicians never actually listen to heart or chest sounds once they leave residency. The use of a stethoscope is either unnecessary, as in radiology or pathology, or delegated to a physician's assistant or nurse who performs the routine blood pressure, pulse, and respiration measurements. However, when a physician first trains her ear to discern particular heart and lung sounds, the experience is inexplicably linked to her stethoscope. The tension in the metal spring pressing the earpieces against the ear canal, the acoustic characteristics of the rubber tube and membrane, and shape of the bell all have an effect on the quality sound. In this regard, listening to the sound produced by the stethoscope is like listening to a musical instrument. Switching to another model—one with a different type of membrane, for example—changes the sound and takes getting used to. For this reason, physicians and other clinicians tend to stay with the brand they first buy or, as is commonly the case, receive as gifts from companies while in training. In addition, since models change very slowly and very little if at all, a lost or stolen stethoscope can usually be replaced within minutes with an identical model sold at any medical supply house.

With the invention of the electronic amplifier in 1905, it was inevitable that the technology would be applied to the stethoscope. But acceptance of electronic stethoscopes for clinical use has been very slow. One of the early hurdles was that the first electronic stethoscopes did not resemble traditional stethoscopes, but looked more like a Walkman® radio with headphones. Companies that focused solely on their superior technology were asking physicians to give up their status symbol, even if it did make subtle sounds more discernable. In addition, with the possible exception of specialists interested in specific disease states, an electronic stethoscope has a negative connotation among physicians. After all, a good cardiologist is a master at listening to the heart through a standard stethoscope and doesn't need an electronic crutch.

Manufacturers of the newest models of electronic stethoscopes address the status issue—at least from the layperson's perspective—by encasing their digital signal processing chips and amplifiers in a shell that looks, for the most part, like an ordinary stethoscope. These look-alikes have a disk-shaped chest piece and earpieces connected by what looks like an elastic tube. This new generation of electronic stethoscopes provides a number of features, such as automatic display of heart rate, a variety of filter modes to simulate the bell or membrane of a traditional stethoscope, the ability to store sounds for playback later, and the ability to play sounds back at half-speed to aid in diagnosis. Some even have infrared links for downloading the sound files directly to a PC for teaching and remote diagnosis, or telemedicine.

In spite of the significant technological advances, companies that produce electronic stethoscopes are having a difficult time selling their products. For most students, the issue is price; prices start at around $200, or about five times what a traditional student stethoscope sells for. Another issue is simply tradition and the teaching of stethoscope use. Learning when and how to use the bell versus the membrane, and how hard to press the chest piece against the chest to get a good seal, is still an integral part of medical education. From the perspective of a doctor's public image, the new units can be easily swung over the neck and, to the layperson, look like an ordinary stethoscope. To other clinicians, however, the electronic crutch is clearly visible—and using it to learn medicine is like training to drive a racecar with automatic instead of manual transmission.

Even as electronic stethoscope manufacturers are discovering that changing physician behavior is going to take more than simply improving the electronics, they are realizing that what they think is a better diagnostic tool may not jibe with what physicians actually need. From a technological perspective, the sound that one of these units creates is very different and changes from model to model. "Improved" electronics may sound good in an ad campaign, but to clinicians it means that they'll have to retrain their ears to the subtleties of yet another instrument when it is time to replace a broken or stolen unit. There is currently no standard those electronic stethoscopes ascribe to, such as the standard organ or piano that modern synthesizers use. Beyond the resistance electronic stethoscope manufacturers encounter now in trying to change clinician behavior, the future for their product looks even grimmer.

Medicine is undergoing yet another transformation, like the one started by Laennec's invention. However, instead of evolving from an art based on interpreting patient symptoms into a science concerned with evaluating objective data, today's evolution is about removing the clinician from the low-level data gathering process while constraining costs. DNA sequencing, whole body imaging, and other technologies generate data that cannot be directly perceived in a patient examination, and yet provide additional clinical relevance. Physicians are becoming managers and directors of data gathering—knowledge workers if you will—in an economic environment where good bedside manner and taking time to connect with a patient is not rewarded by the cost-conscious system. It is more likely that clinicians of the near future will be associated, through necessity, more with a medical PDA than with a stethoscope. Like the physicians on Star Trek, modern physicians will use intelligent devices and handheld sensors to gather data they can interpret. Of course, this also presents the physician community with the adoption challenges similar to those originally ascribed to the stethoscope.

The history of the stethoscope exemplifies the need for decision makers to know their customers, and then figure out how such knowledge can maximize the likelihood of success in bringing a product to market. Additionally, this example demonstrates how the initial adoption rate by users of a new technology is constrained by prior experiences and personal beliefs.

Virtual reality, pervasive computing, hybrid gas-electric cars, smart clothes that change to suit the wearer and the environment, and nanobots that perform surgery while patients sit comfortably watching their progress on a computer monitor are all inevitable. However, convincing surgeons to trade their scalpels in for unfamiliar nanobots and motivating style-conscious consumers to give up their sports cars for energy-efficient hybrid sedans is a battle that will take time and energy. Despite the envelopes of technology and high-tech banter, the vast majority of consumers are creatures of habit.

It is certain that society is plunging headlong into a future where information is no longer personal, but is stored and accessed on the net through portable and mobile wireless devices. However, achieving that future in a timely, affordable manner involves a complex technical, political, and social evolution. A prerequisite, but by no means a guarantee, for this evolution is that new technology must provide an incentive for consumers to change their behavior—it must offer a value that is not available any other way.

The inevitable breed of personal appliances with embedded intelligence, from smart refrigerators that track the age of perishables and order replacements online, to medically diagnostic toilets, must, at a minimum, save customers increasingly precious time. A smart microwave oven that recognizes that a frozen dinner taken immediately from the freezer needs to be defrosted with short, intermittent bursts of microwave energy before it can be cooked at full power would seem to have an immediate niche market. For example, a busy professional just home from work may not want to contend with the minutiae of defrosting and then fully cooking dinner. However, for the professional who looks forward to time in the kitchen as a creative outlet and a place to escape from the control of technology, a smart microwave oven has no value.

For a technology to be accepted by potential customers, not only must the customer perceive it as useful, but it has to attract a critical mass of other users as well. A critical mass of loyal users beyond the initial early adopters helps to ensure that a product will not be abandoned and provides the producer with an economy of scale that allows the producer to offer the product at a reasonable price. For example, the fax machine is a valuable business tool by virtue of the number of businesses and customers who use the fax for instant communications. It is only because so many businesses and customers can send and receive faxes that the fax machine, based on a less efficient, pre-email, paper-and-ink technology, is practically indispensable in business. In contrast, the NEXT computer, Apple's G4 Cube, and Chrysler's 1935 Airflow De Soto—all technological and design marvels ahead of their time—appealed to a small number of individuals, but failed to catch on with their target customers. The Airflow De Soto, for example, sported an aerodynamic design at a time when every other model offered square, boxy cars, and had a new suspension design that provided a smoother ride than the competition. Even though the technology was innovative and solid, the look was too different from what people considered normal for a car, and the De Soto was retired.

For a product to be successful, it must be accepted by individuals as well as a population of users of sufficient size to support production, maintenance, and ongoing research and development. These two views of customer behavior—one at the individual or micro level and one at the macro or population level—are discussed in the next section.

A customer's perception of the benefits and risks associated with adopting a new product or service affects the bottom line of every business enterprise. After all, if a customer has a need for a product, then every component and contribution of the value chain of which it is the result—from the stability of the underlying technology to the efficiency of the manufacturing process—is irrelevant.

Predicting individual customer behavior when faced with a new product offering is no trivial task, given the dozens of variables involved. That is, a customer may shun a product because of religious beliefs, political opposition to such technologies as bioengineered foods or nuclear energy, poor product performance and quality, and lack of awareness because of ineffective marketing. A customer may see no clear benefit in using a product; that is, it may seem too expensive, too difficult to use, take too much time and effort to learn, and may not provide an obvious advantage over traditional approaches. A customer may simply be resistant to change and fear the unknown.

However, in today's business environment the executive manager has a variety of tools to help gauge the consumer's purchasing habits. With knowledge of personal styles, it is possible to predict, with a fair degree of accuracy, how a customer is likely to respond, for example, to an offer for a new computer or piece of office equipment. However, getting at that information is still very difficult, even with the large electronic databases that companies compile on U.S. citizens. An alternative approach is to model individual behavior based on accepted psychological models of generic human behavior.

One way for a decision maker to gain some degree of control over the demand and subsequent purchase of a particular product is to model individual customer behavior change. A popular model of behavior change that is used successfully in everything from dieting to smoking cessation is the Stages of Change Model developed by two clinical psychologists, James Prochaska and Carlo DiClemente, in 1979. It assumes that every customer goes through five discrete, predictable stages when making a major behavior change, such as a purchase and then adoption of a new product. The stages, labeled 1 through 5 in Figure 3.1, are:

Precontemplation

Contemplation

Preparation

Action

Maintenance

A sixth stage that is often considered part of the model, Termination (of the original behavior), is not included here to simplify the discussion.

- Precontemplation.

In the precontemplation phase (1 in Figure 3.1), a customer typically has no knowledge of the alternative technologies available, and no plans for changing his or her behavior. At this stage, a customer may selectively filter information that justifies his or her decision to stick with current behavior.

The goal of many marketing campaigns is to move customers out of their comfort zone of precontemplation and create an awareness and desire for new products and services. Because the time and energy for consumers associated with maintaining the precontemplation phase tends to be sporadic and low, it may last for days, years, or, in some cases, a lifetime. Only when the customer becomes aware of a product that promises a time or energy savings is a customer motivated to leave the steady-state condition of precontemplation.

- Contemplation.

During the contemplation phase, a customer assesses the investment in time, energy, and money associated with purchasing a product. As depicted by 2 of Figure 3.1, the contemplation phase of behavior change includes a modest, increasing investment of time and energy. The ramp-up in energy expenditure may be instantaneous, as in an impulse buy, or occur slowly over weeks and months, depending on the nature of the behavior change. This stage is often characterized by ambivalence about changing, and a customer may waver between staying in her comfort zone and venturing out into the unknown because of the risks she associates with changing behavior. A customer can contemplate a purchase indefinitely. These first two states of change, with their risk of slowness, can determine the rate of behavior change or the pace of product adoption.

- Preparation.

During the third phase of the Stages of Change model, preparation (3 in Figure 3.1), a customer makes the decision to change and takes steps to prepare for the change. Preparation typically requires only a modest expenditure of time and energy over that already invested.

- Action.

In the action phase of behavior change (4 in Figure 3.1), a customer is actually making a change. That is, a customer is expending energy and time, throwing aside previous behaviors in favor of the new product. It is during the action phase of behavior change that impediments to change become most apparent and decrease the odds that the behavior change will be long lasting. Impediments to change include:

Social pressures to maintain the old behaviors

Uncertainty in the payback of the energy and time invested in the new behavior

Difficulty in practicing the new behavior

Extended training requirements

Significant and unexpected monetary requirements

Frequency with which the former behavior was practiced

Disbelief in the efficacy and worth of the new behavior

The challenges of succeeding during the action phase are represented by the left arrow in Figure 3.1. If the challenges associated with taking action are too great, as depicted by the enormous time and energy requirements in curve C, then a customer is likely to travel backward through the behavior change model, that is, revert to old habits.

Similarly, the likelihood of recidivism is greater if the time and energy required to maintain the new steady-state or baseline behavior is not significantly lower than that associated with the initial behavior, as in curves B and C. In this respect, the probability of recidivism is a function of the relative time and energy required to maintain phase 1, or precontemplation, versus the end of phase 4, or action. This relationship, the Recidivism Gradient, is illustrated in Figure 3.2.

- Maintenance.

The final phase of behavior change, maintenance, represents sustained behavior change, where the energy and time associated with the behavior is constant. Ideally, energy and time expenditures are along the lines of curve A in Figure 3.1; but the less than ideal expenditures described by curves B and C are also possible. The maintenance phase of one behavior change sequence becomes the precontemplation phase of the next. That is, even if a customer is happy with his purchase, a model that is newer, more efficient, and easier to use may eventually appear on the market. However, the company that is first to market with a new technology product has the opportunity to establish brand recognition, consumer loyalty, and market share, thus creating a market dominance that may be difficult for a competitor to overcome with only a marginal improvement in features.

To illustrate the Behavior Change Model as applied to product adoption, consider the case of Sam, a busy business professional. Up to this point in his career, Sam has ignored the modern status symbol for the technical elite, the PDA. He is happy with the paper-based organizer that he has used since graduating with his MBA a decade ago, and ignores the PDA displays in the office supply stores (precontemplation). However, about a year ago, Sam noticed that the latest model of his organizer binder now provides a free lightweight holster for a PDA. That night, he also noticed an advertisement in the newspaper for a sale on PDAs.

The next morning, Sam spent a half hour talking with coworkers about their PDAs, the various options, which brands are the most popular, and other details (contemplation). During his lunch break, Sam read through several PDA reviews posted on the Web, and compared prices at the various mail-order centers (preparation).

On the one hand, Sam was ready to make the move to the timesaving technology that his coworkers enjoyed, but on the other, he feared the loss of his personal and business data. In the end, however, the PDA won out because of the prospect of time savings, ease of tracking prospects, the smaller size of a PDA, or simply looking cool. That evening, after discussing the purchase with his wife, Sam called one of the mail-order computer companies and ordered a PDA (action).

Although it took more time than he anticipated, Sam began the process of entering his calendar and contact information (his behavior is represented by the upward sloping curve of the action phase in curve A). After a week carrying the PDA and learning to use the stylus, entering and retrieving personal contact information was easier (curve A). Sam no longer took the time to write down everyone's contact information, but simply accepted their contact information beamed through the infrared (IR) link between their PDAs (maintenance). Furthermore, Sam was able to rest assured that the data on his PDA was backed up on at least one PC—a feat that he could not accomplish with the paper organizer that he was constantly in fear of losing.

After about three months, Sam's PDA was fully integrated into his life to the point that it disappeared from his conscious thoughts. His focus turned to other issues at work and home (precontemplation). About a month ago, a little less than a year since he first purchased his PDA, Sam noticed an advertisement for a wireless version that provided access to email and the Web. He wondered if the wireless unit, which was somewhat bulkier and heavier than his current PDA, would save time (contemplation). Sam went to the Web and looked over reviews, explored monthly service charge options and the extent of service coverage in his area (preparation). He ordered a wireless PDA from the same mail order firm that sold him his original PDA and had it delivered overnight (action). Transferring his contact and calendar information to the new unit was straightforward, and after spending a few hours with the manuals, Sam began using the PDA the next week at work.

Unfortunately, Sam found the email function less than optimal, because he had to continually log in to the device to check for messages. In addition, he found that coverage inside his office building was spotty, and sometimes he could not send emails without going to a window down the hall. Together with the added bulk and weight, the inconvenience of the new PDA simply was not worth the aggravation (curve C of Figure 3.1). He returned the wireless PDA and went back to his old PDA and decided to revisit the wireless PDA in a year, when the next generation of wireless devices should be available (back to contemplation).

An understanding of changes in patterns of customer behavior at the population level is critical for the success of any technology-based product in the marketplace. That is, although the market is derived from the actions of individual customers, the ability to predict the behavior of large groups of potential customers is critical in planning and establishing price, product performance standards, and customer expectations.

The technology adoption curve is a common means of modeling customer behavior at the population level as a function of time and the number of customers involved (See Figure 3.3). According to the model, as soon as a product is introduced, a small number of technology-focused innovators go to great lengths to acquire it. Often the innovators are price insensitive, and are willing to pay unreasonable sums to be the first in their peer group with the smallest, thinnest, or most powerful gadget. Later, the educated, but less technologically aware early adopters follow the innovators' lead and invest in the technology. The major influx of customers constitutes the early majority, followed by the late majority. Finally, the laggards, who tend to be less educated and less economically able, buy into the product.

The technology adoption curve describes the history of the stethoscope as well as more recent innovations, such as the PDA. Returning to the history of the stethoscope, after Laennec's original innovation, it took about a decade for the innovators and early adopters to embrace the technology. However, because a fundamental structural change in the nature of medical practice was required for wider adoption of the technology, it was not until a thought leader formally accepted what would now be considered the stethoscope that the early majority of physicians committed themselves to learning the technology and teaching it to their students. Today, every medical school graduate in the United States—even the late majority and the laggards—must demonstrate some proficiency with the stethoscope. However, if the potential population of customers for the stethoscope is extended to physicians and other medical practitioners around the world, then the late majority is still adopting the stethoscope. Many practitioners of Eastern medicine, for example, have yet to accept the stethoscope as a valid instrument in the practice of their healing art.

As a more recent example, consider the history of the PDA, typified by the PalmPilot, Visor, Blackberry RIM, or any number of the so-called CE (Microsoft Compact Edition operating system)-compatible units. Throughout the 1980s several manufacturers, including Casio and Sharp, introduced pocketable electronic devices for saving names, addresses, phone numbers, and notes. However, the Apple Newton MessagePad 100, introduced at the MacWorld Expo in 1993, was the first pocket computer that resembled modern PDAs. When the Newton was first released at a MacWorld Expo in Boston, a line of customers stretched the length of the conference center—simply to get the chance to buy an untested Newton at full retail price. The fact that the original Newton was large, clunky, and, by today's standards, slow, did not matter. To these innovators, possession was enough.

Two years later, in 1995, Apple introduced the MessagePad 200, which improved the technology of the 100 with a new version of the operating system. Many innovators again jumped at the chance to own the new Newton model, but additional sales beyond those to early adopters were minimal. In the next few years, despite upgrades and new models with additional features, the Newton still failed to attract the attention of users other than the initial early adopters. There was no champion for the technology and the unit was still too bulky compared to the nearest alternative, a paper calendar system. By 1998, the Newton was officially discontinued.

Despite the Newton's failure, PDAs proliferated. In 1995, the time of MessagePad 100's release, U.S. Robotics, known for their communications modems, introduced The Palm 1000. The Palm 1000 and successors, the PalmPilot series, soon became the overall favorite because of its simplicity, size, and ease of use. By the time the Newton was discontinued in 1998, early adopters were enjoying their PalmPilots. Because the price was right and the technology was readily accessible, Palm, later joined by numerous Windows CE-compatibles and RIM's wireless Blackberry PDA, rapidly gained acceptance in the business world. Today, customers in the late majority are buying into the concept of the PDA for use in grade schools, university classrooms, and the boardroom.

Few products or categories of products follow the symmetry of the generic curve in Figure 3.1. Most go through periods of different adoption rates, as customer behavior is influenced by depressions, recessions, war, and other external factors. Figure 3.4 illustrates the technology adoption curves for the TV, cell phone, PC, and Internet. Even though the rate of adoption of the PDA over a decade may seem slow, many technologies, even those considered essential for everyday business, can take decades to reach the early and late majority.

The telephone, for example, which was patented in 1876, was initially viewed by most people as a technologic oddity with no apparent practical use. Most of the general public considered it to be an eyesore. This is not surprising, given that the first phone systems consisted of two phones and a private cable—the electronic equivalent of two cans and a string—run from one business to another or from a home to a business office. The result was streets choked with private cables strung directly between pairs of phones, because a comprehensive telephone network had not yet been invented.

Customer service and product choice began to improve for the average consumer when Bell's telephone patents ran out in 1894. From that time onward, new, competing phone services were constructed, and these systems included the working middle class. Even so, the adoption rate hovered around a third of all households until after World War II. With the prosperity of postwar America, adoption rapidly increased to the laggards (nearly 90%) by the 1970s.

Television has had one of the fastest adoption rates. Regular TV broadcasts began just before World War II, mainly showing boxing matches in bars and other commercial establishments. Black-and-white TV was introduced to the working class around 1947, and color TVs, about eight years later. In only four decades, TV had penetrated 98% of households. Most consumers consider TV, like the telephone, a necessity.

As shown in Figure 3.4, the fast growth in adoption of the TV occurred during the first few years after introduction. In the eight years from 1947 to 1955, over 60% of households—the early and late majority—purchased a TV. TV's pattern of adoption is probably a good predictor of how successful the home PC and home Internet connectivity will be, because they are following the same adoption rates relative to their introduction times.

Although population adoption rates reflect group behavior, some of these behaviors are constrained and directed by economics, legislation, and business practices. For example, while the adoption of cell phones is about 40% and growing rapidly, legislation against driving and cell phone use, and health concerns over potential links between cell phone radiation and cancer, may slow the adoption rate.

Similarly, the growth in Internet adoption rates may be limited because of payment options. AOL, the largest Internet service provider (ISP) in the United States, requires users to pay with a credit card, which effectively excludes almost one-third of the population, who do not have credit cards. Although there is a longstanding debate over whether the government should sponsor content development and provide public schools with free Internet access, the current reality is that expansion of the Internet is still very much restricted to the privileged within the United States.

Of all of the parameters that affect customer behavior, price and value are primary considerations. For example, despite increased use of cell phones worldwide since their introduction a little over two decades ago, rates of adoption of wireless services dropped as part of the worldwide economic technology slowdown in 2001. Even Nokia, the world's largest cellular phone maker, reported its first drop in earnings in five years in 2001. In the tight economy, potential customers simply were not willing to pay the asking price for the new added features. That is, in order for potential customers to change their behavior and become actual customers, price increases must be in line with the incremental value of added features and services.

When it comes to evaluating the value of added features to potential customers, whether the feature is a larger screen size on a cell phone or racing stripes on a sports car, several methods are available. The traditional method is to have an expert, third-party appraisal of a product with and without the added features. Although this method may be useful for establishing the value of established, large-ticket items such as cars, it is not practical in the real-time, high-technology marketplace, where there may be no recognized experts in a new technology, much less add-ons.

The value of added features and services in modifying customer behavior is often determined with hedonic pricing techniques, in which the characteristics of a product are unbundled and priced separately. Hedonic pricing, which has been used by the U.S. Bureau of Economic Analysis for the analysis of computers and peripherals since 1985, establishes the worth of each characteristic of a high-technology product from RAM to hard disk space. Wireless capabilities add value to a PDA, for example, but the increased price must be in line with the potential customer's perception of the added value in order for the PDA to sell.

Hedonic pricing is especially useful in establishing the value of aesthetic or more ephemeral product features. For example, ease of use has a value that is separate from the underlying technology, a fact that Apple used to its advantage in marketing campaigns in the pre-Windows era. Similarly, compatibility has value that is dependent on, but separate from, the value of the operating system software and computer hardware.

To understand whether the addition of features or value to a product will appeal to customers, it helps to consider the spectrum of customer expectations. As in hedonic pricing, expectations are the result of qualitative and quantitative assessments of features and services, which cannot be completely established by simply measuring the clock speed of a computer or the zero-to-60 acceleration time of a sports car. The minimum functionality that customers are willing to accept from a product at a given price varies. For example, Sam had a minimum set of expectations surrounding his new wireless PDA that were not met, so he returned the unit. Less demanding users might be satisfied by the PDA, especially if they are not concerned with operating within buildings but are content to have any wireless connectivity to the Web, even if it means walking to a window.

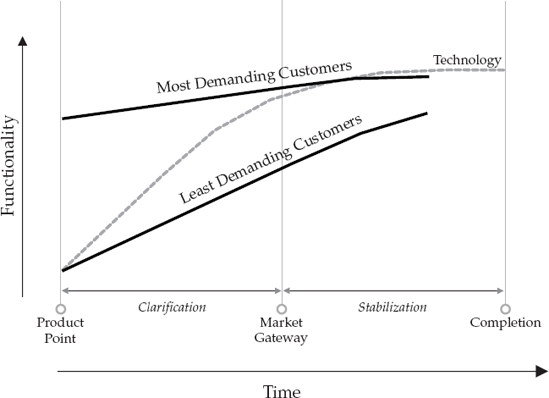

Figure 3.5 graphs customer expectations of functionality versus the time since the Product Point in the Continuum, assuming price holds constant. Note that customers expect the functionality of a product line to increase over time, especially with a technology-based product, and potential customer expectations are linked to the technological maturation of a product in the Continuum. This linkage is the result of advertisements, articles, increased competition within the marketplace, and other forms of press coverage. Most potential computer buyers expect, for example, that the clock speed of microcomputers will increase every year, and that processing power will double every year or so, as predicted by the well-publicized Moore's Law.

As shown in Figure 3.5, there is a range of customer expectations for functionality. At the Product Point in the Continuum, the least demanding customers are willing to pay the asking price for the functionality provided by product. However, the most demanding customers are not willing to invest in a product that has not proven itself or has a few loose ends that need to be fixed before it is acceptable. For example, Sam will not be satisfied with wireless technology until he can use the PDA anywhere in his home or office. Sam may have to wait until the technology underlying wireless PDAs is nearly at the Product Point in the Continuum. An obvious alternative for Sam is to find a competing wireless PDA product and evaluate the value it provides in terms of functionality and price.

Note also in Figure 3.5 that the spread in expectations narrows as the technology matures along the Continuum. This phenomenon is obvious today in the desktop PC, where all potential customers expect a PC to come equipped with a CD-ROM drive and floppy disk drive, at least 128 MB of RAM, a sizeable hard drive, and a 1 GHz or better processor, regardless of their intended application. The desktop PC is a commodity, and there is increasingly less difference between configurations from one model to the next.

Given the customer behavior illustrated in Figure 3.5, the challenge for the marketing division of a company developing a product from the Product Point to the Market Gateway is to communicate the functionality of the product to those potential customers that fall below the technology curve of the Continuum. For example, it is a waste of corporate resources to market wireless PDAs to customers like Sam, represented by the most demanding customer curve in Figure 3.5. Marketing dollars would be better spent on communicating to less demanding customers (early adopters), and then including the more demanding ones (early and late majority) later in the Continuum.

In business, the political, social, and financial climates often dictate customer and corporate behavior that would otherwise seem out of line with the value proposition. For example, stem cell research based on embryonic cells was at least temporarily banned in the United States. Because of the ongoing controversy over whether embryonic stem cell research will be allowed or even actively supported by the U.S. government, many international biotech firms invested their efforts in countries with more politically favorable climates. For example, the United Kingdom's biotech industry, second only to that of the United States, has the full support of the British government. Why should a multinational company fight a national government when it can easily invest its resources overseas?

Similarly, the after-effects of the last energy crisis in the 1970s are still affecting innovation in energy production in the United States. When Congress passed the coal credit in 1980 to encourage businesses to turn domestic coal into a substitute for foreign crude, the effect was to focus innovation on complying with the tax credit stipulations. Paradoxically, the synfuel laws have rewarded companies that use oil as a major ingredient in the coal processing operation, in order to be eligible for the tax breaks. As a result, the public pays about $850 million per year to subsidize energy companies. The supposed intent of the legislation, to foster innovation to create more energy-efficient alternatives to crude oil, has been abandoned. Why should a company invest millions of dollars in R&D for a coal processing plant when spraying coal with waste oil can generate a tax credit of $26 per ton?

As most marketing professionals know, linking emotional issues to otherwise undifferentiated me-too products can often make the difference between product failure and market leader. One of the most obvious examples of this phenomenon is the segment of the U.S. consumer population that responds favorably to "green" products, which are ostensibly friendly to the environment. Energy Star, sponsored by the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) and Department of Energy is the modern equivalent of the Good Housekeeping seal of approval for energy efficiency. Energy Star labels everything from computer monitors that go into power-saving mode after periods of nonuse to entire buildings. An ad campaign aimed at CEOs that appeared in Forbes Magazine through the summer of 2001 emphasized the public relations value of the label because it "tells the world that you are committed to superior energy performance."

Regardless of whether the products are mutual funds that invest in companies that recycle their waste paper or sweaters made from recycled plastic bottles, the green label appeals to many potential customers. Some customers are willing to pay a premium or go out of their way to buy green. That is, the green designation has hedonic value to many customers, above the value of incorporating postconsumer waste in ordinary products such as tissue paper. This value may be derived from peer pressure or the belief that they are doing good. In order for the green value to have a lasting behavior change, the effort required to go green should be minimized, and the value should be comparable to nongreen products. For example, with customers purchasing a new computer monitor, selecting a model that complies with Energy Star should be a simple matter of identifying the appropriate sticker. In all other aspects, the monitor should be equivalent in quality and performance to noncompliant monitors.

Another area where customer behavior is under heavy influence from governmental regulation is that of electronic publishing. Consumers have not yet fully embraced the concept of eBooks, even with the likes of Stephen King contributing to the medium. Part of the issue is economic: consumers are used to free electronic content on the Web, whereas they pay for print materials. There is also the general public's perception that works published through traditional channels have a higher quality than electronic documents. Anyone can post content to the Web and claim to be an expert in any area.

Part of the conundrum facing electronic publishing is the status of eBooks, or books distributed in electronic form and intended to be read on a Web browser, PDA, or dedicated eBook reader. Adding to the confusion are publishers' claims regarding their right to maintain copyright control over books that have been digitized for distribution over the Internet. The court challenge of companies offering electronic versions of books that were originally copyrighted as "books" received center stage attention in July 2001. Within a period of about three weeks, not only did the courts issue a ruling preventing traditional publishers from blocking the electronic distribution of newly digitized works that were not specifically under contract for electronic distribution, but the first full-length eBooks were submitted for electronic copyright registration to the U.S. Copyright Office, and the Library of Congress established a digital book collection. At the same time, the FBI arrested a programmer for selling a program that defeated the anti-copying-protection mechanism built into Adobe's eBook Reader software (one of the most popular eBook reader programs on the market). The illegal software gave customers who had purchased an eBook from the Web the ability to access their eBook on multiple machines—desktop PC, laptop, or handheld PDA. Without the software, customers have to purchase a separate copy of an eBook for each location—a major impediment to the widespread adoption of eBooks.

In all of the preceding discussions, the basis for how customers have and will likely respond to products and services depends on having access to customer data through primary or secondary market research. Customer information has to be immediate and timely to have any predictive value in the marketplace. As such, in today's digital economy companies are investing money into customer relationship management (CRM) programs, data mining, customer profiling, and other automated means of combing through hundreds of thousands of profiles and identifying likely return or new customers.

At issue, from the customer's perspective, is individual privacy—whether they are being watched or seen is of paramount importance. Virtually all customers are averse to the former, and will go out of their way to avoid creating records of their activities for the government or big business to ponder and analyze. If the latter, then most customers are at least willing to provide merchants with access to account balances and similar financial data so that they can make purchases on credit, apply for a home mortgage, and conduct other business transactions without having to produce a box full of documents.

Not surprisingly, one of the impediments to eCommerce is the ease with which customer information can be acquired, collected, traded, and sold. During the collapse of many dotComs, the first asset to go on the table was customer data, in the form of purchase history and demographic information. As a result, it is possible that "trusted" information once part of the customer–client relationship is now in the hands of the government and any number of click-and-mortar companies. The overall effect has been to reduce the trust level of customers who would otherwise engage in eCommerce.

Regardless of how well an idea is transformed into a product, in the end, customer behavior dictates success or failure of the product in the marketplace. As such, an understanding of how individual customers come to a buy decision, as well as how populations of customers behave, is critical to the economic success of a product. With an appreciation for and understanding of the factors that influence customer behavior—from individual personality styles to government regulations—decision makers can analyze which market opportunities are best suited for their companies' business directions and quickly take advantage of them.