If necessity is the mother of invention, discontent is the father of progress. | ||

| --David Rockefeller | ||

One way of looking at the world of business is as an imperfect system ruled by chaos, where chance and fate define the ultimate outcome of any personal venture or enterprise. This view is supported every few decades by the large number of people and companies who profit simply because they seemingly happen to be at the right place at the right time. In the 1970s, for example, investing in real estate in the United States was a sure thing. Anyone with enough money to invest in real estate was virtually guaranteed a return on investment whose rate would beat the prime rate if they held on to the property for a year or two. Early investors in the dotCom companies saw phenomenal returns as well—as long as they did not hold on to the stock too long. It was so easy to make money on tech stocks that many people quit their regular jobs to become day traders. However, this state of affairs was short-lived. The fundamental and underlying understanding of when to invest or divest is the true power of the successful visionary business alchemist. The ever-present question is: When will the next wave of opportunity hit and how can one identify the proper timing to enter a new market?

One way to approach that question is to look at the world as a complex web of cause and effect, where some events can be controlled and other factors cannot—either because of their nature or because we are unaware of their existence. In this view, there are good times and bad times as well, because the economic foundation is continually shifting. What is more, the rate of change in innovation is accelerating in part because of the development of communication technologies. For example, instead of an unaware developer wasting time on an invention only to find out too late that something like it was patented years earlier, anyone can log in to the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office (www.USPTO.gov), search the archives, and even order drawings by fax.

This second view of the world is also compatible with the notion that the conversion of ideas to saleable products is a partially controllable process that replaces variability and uncertainty with known or knowable technology, as described by the Continuum model. In this regard, the Continuum model is helpful in reducing the degree of uncertainty in the conversion process. It shows, for example, how the role of marketing at different points varies as a function of whether the business is newly established and has limited resources or is established and has a marketing division in place to direct R&D efforts. A marketing division also evaluates new and emerging product ideas. The model also illustrates how the chances of a typical garage startup software company succeeding are compromised by an inability to address—or lack of knowledge about—market needs, as opposed to technologic function.

A third view (compatible with the second view) is that businesses, whether lemonade stands or Fortune 500 companies, are fundamentally organic structures and behave in characteristically organic ways. That is, businesses and their products wax and wane with the economic environment. For example, companies rarely stay on top of their market for more than two or three decades, and the few companies that have done so did it by recreating themselves in response to changing customer and economic demands. Although a successful business can be replicated endlessly when a people-independent process is established, someone or some group has to first establish the process. Since these people have a finite career-span, change is inevitable when they retire. It is unlikely that their successors will see a way to do things better—if only to take advantage of a new technology or to create a legacy of their own—unless a successful knowledge transfer is completed between new and old.

This is comparable to the concept of peaking for an athletic event. With an established learning curve that includes understanding the proper training, rest, nutrition, and motivation, it is possible to stay at a moderate to high level of fitness indefinitely. However, for peak performance, it takes planning, mental and physical preparation, motivation, and the necessary skills and aptitude. However, even a professional athlete can only sustain a peak for a limited period. It is unusual for an individual, company, or country to stay in peak state for more than a few decades. Consider that when President John F. Kennedy established the goal of landing a man on the moon, the military (NASA) and hundreds of contractors focused on achieving the goal at any cost, as a means of winning a psychological edge in the Cold War against Russia. As a result, there were more innovations in physics and aircraft engineering in a few years than in the previous two decades, with engineers and scientists devoting long hours and weekends to achieving the goal—akin to the work ethic of the dotCom startups. Of course, it helped that the contractors had a blank check from the Kennedy administration. However, after the illusive goal was achieved, life for the engineers returned to normal, and the rate of innovation slowed as well. Once the dream was achieved, there was no sustained vision or next step in the process.

Similarly, as products mature, they eventually become feature intensive rather than innovation driven, and margins drop. For example, in the high-tech industry, IBM and DEC were the market leaders in the 1980s because they controlled large proprietary systems that were popular with businesses. In the 1990s, with the introduction of the PC, Microsoft, Dell, and Intel dominated the space, displacing the mini- and mainframe computer manufacturers. In the first decade of 2000, wireless handsets, including wireless PDAs, are poised to displace the PC and its associated technical infrastructure in terms of the number of devices used daily for creating and disseminating information.

Continuing with a view that combines the deterministic and organic views of business, this chapter examines how to use the information introduced in the previous chapters to make better business decisions. The discussion begins with a review of the factors associated with success in business, is followed by an examination of some business concepts that surfaced during the New Economy, and finishes with a discussion of how the Continuum model can be useful to startups or established companies with either technology- or market-driven products.

Assuming that the fate of a business is not predetermined and that decisions can define or establish the direction for progress, much of the fate of a business rests squarely on the shoulders of the CEO and other executive decision makers. Through directing the focus of the company, managing risk, creating a shared vision, and determining the proper timing of events, a CEO can create a successful culture or bring a company to a screeching halt.

For example, the new GE simply is not the same without Jack Welch at the helm, just as Intel is still partly defined by Andy Grove's legacy. Similarly, Chrysler would never have succeeded in the same fashion without Lee Iacocca. Great CEOs not only excel at recognizing markers of progress along the Continuum model, but they are keyed into the significance of personal relationships and the business environment. As noted in Chapter 3, the motivation behind exemplary performance as a leader is often difficult to determine, although it is possible to guess in some cases. For example, Lee Iacocca was fired from Ford only to lead Chrysler out of the doldrums. Whether his success at Chrysler was because his failure at Ford motivated him to prove to the world that it was not his fault is debatable. However, what is not debatable is that he managed to pull the company out of a slump. For example, he single-handedly obtained a loan for the company from Congress, and cemented his image as a man of his word by paying back the loan before it was due.

Iacocca also illustrates a characteristic of winning leaders. Success is not about avoiding failure, but about managing failure when it occurs. For example, Iacocca left Chrysler and went on to champion a battery-powered bicycle that flopped. Undaunted, his next move was to a make a battery-powered vehicle that has the potential to do well, especially in California. Whether or not the vehicle is a success, the point is that Iacocca keeps stepping up to the challenge, win or lose.

Another characteristic of successful leaders is the ability to clearly define the focus of the enterprise. Seasoned CEOs are aware of the need to constantly balance resources throughout the Continuum, from product development to marketing, as the technology moves along the Continuum. In addition to external economic factors, customer acceptance of a product in the marketplace is crucial. The odds of success are greater if the customer is considered as early as possible in the Continuum. Moreover, it is critical to appreciate that customer behavior change takes time and energy. A marketing campaign that begins after a product is fully test-marketed may fail in the larger marketplace because the product may sit idle for years before market demand is sufficient to warrant large-scale production. However, the time horizon to build a critical mass of customers to sustain revenue may go beyond the initial seed capital that the company started with. The time required for universal adoption is far greater than the life span of a typical company, suggesting that timing is a major factor in the success of introducing customers to a product. Furthermore, even if the company has the resources and bandwidth to wait for customer willingness to accept the new product, the threat of competition introducing a superior technology at a lower price is ever present.

Success in the marketplace is a matter of timing and accurately communicating a product's benefit to the end user, as well as the creation of a working technology. History is full of great ideas that failed in the marketplace because of timing. The Commodore Amiga, circa 1985, was ahead of its time as a digital video- and audio-editing machine, comparable in many ways to contemporary tools available on Windows and Macintosh. Despite the Amiga's technical superiority, which included video capture and playback hardware and editing software, marketing was not able to save the technology in the marketplace—there simply was not a big demand for digital video editing outside of the small niche professional market. As it was, the Apple Macintosh at that time was pushing the technology adoption envelope in the general consumer market with its grayscale graphical user interface. Conversely, the Apple Newton PDA and the NEXT computer were released into the hands of marketing and sales long before the underlying technology was ready. Apple and NEXT computing apparently failed to follow the Continuum model, hoping that marketing would take care of holes in the technology.

Finally, the role of decision maker carries with it the responsibility of seizing opportunities as they arise. Since opportunity implies risk, a large part of a decision maker's job is to manage risk. In this regard, risk management is not about doing whatever it takes to avoid disaster, but rather making plans to respond to disaster when it strikes. For example, risk management includes setting aside money, time, and other resources to deal with failure. A CEO who is good at risk management can quantify risk so that specific risk-management actions can be instituted to solve the challenges at hand.

During the technology bubble of the late 1990s, there were a number of New Economy misconceptions that were thought to be applicable to all present and future business practices. These misconceptions, which were then embraced by at least some of the companies taking part in the dotCom boom, are no longer viable in today's business world. A discussion of these outdated maxims follows.

The advantage of being the first or second company to offer a new type of product in and of itself does not guarantee success over the competition. Being an early mover in a new product space is just as important as being a best mover. Microsoft illustrates this by its late but ultimately successful entry into the Web browser market. Similarly, once Corning demonstrated the feasibility of fiber optics as a communications medium, AT&T responded immediately by pouring resources into the space and soon dominated it.

During the dotCom boom, the belief that simply claiming a catchy URL planted a company flag in the dotCom space was short-lived. Of course, being a first mover with deep pockets and a good long-range financial plan is optimal, as are speed and agility in responding to change in the economic environment, including meeting ever-vacillating customer preferences.

Companies and even countries with vast resources do not have to be first movers to dominate a consumer market space. The second mover has the advantage of watching and learning what does and does not work for a target market. For example, China was a late mover in the wireless space, behind Japan, much of Europe, and parts of the United States. However, as soon as China decided on its wireless strategy, handset cellular network providers around the globe responded immediately to service China's needs. In watching the progress of wireless in more advanced countries, China's governmentally controlled telecom industry was able to sidestep the fallout from mergers and acquisitions and was in a position to judge the technologies and companies that survived the shakeout.

One of the advantages of interactive advertisement over traditional print and TV advertising is that it is possible to determine how many people are actually exposed to an ad. However, as the banner ads on Web sites demonstrate, most users ignore ads, and the return on investment for Web advertisers has been much lower than initially expected. In other words, the practice of establishing the valuation of a Web site based on the number of visitors to a site has proven to be a poor strategy for financial valuation. On the Web, as in other touch points—print, TV, and radio—what counts is the conversion rate, the number of potential customers who are exposed to an advertisement and then actually form a business relationship with a company.

Because of the Internet, a Web site residing on a PC in the dormitory room of the teenager who created it has the same level of access to the global market as does IBM or Microsoft. As such, with enough attention to detail and relevant content, it is impossible for the casual viewer to determine if the company behind the site consists of one or one thousand people. However, the Web has demonstrated that a prerequisite for a company to be successful globally is success locally. That is, a business process must be perfected locally before attempting the much more complex global market.

Companies have to succeed in their local economies and establish a supporting infrastructure before they can establish a global presence, even if they have a global reach by virtue of the Web. Entering and successfully competing in a global market is much more than being accessible, as there are localization issues with user interface design, cultural issues, language, currency conversion, taxes, and other service-fulfillment limitations inherent in dealing with a global business.

Technology can amplify a good or bad customer service strategy, but technology should not be confused with strategy. Good technology, whether it takes the form of a properly implemented Web site or a CRM program, can make a good service strategy great. However, the inappropriate use of technology can make a bad strategy even worse.

In most successful service businesses, technology takes a back seat to the personal element. For example, as described earlier in this book, the human factors associated with technology adoption are much more critical to success than the specific technology involved. Employees involved in customer service typically fear change, do not want to lose the power they have accumulated, and are generally uncomfortable with revolutionary, as opposed to evolutionary, changes that technology can bring about. Without addressing these issues as part of an overall customer service strategy, any technology push is destined for failure.

The fate of Amazon.com and the other high-profile players in the Web space have demonstrated that a focus on market share at the expense of profitability only works in the short term. Although the strategy of being growth-driven may initially work to gain market share and displace potential competitors, successful long-term companies are profit-driven.

For example, Amazon was growth-driven during its first few years, but then pressure from shareholders for a return on their investment forced it to become profit-driven. The online retailer and bookseller was forced to adopt cost-cutting measures, such as using customer support representatives in India and elsewhere instead of domestic staff. It also established profit-generating business relationships with Circuit City, Toys R Us, and other brick-and-mortar stores that could benefit from—and pay for—Amazon's reach.

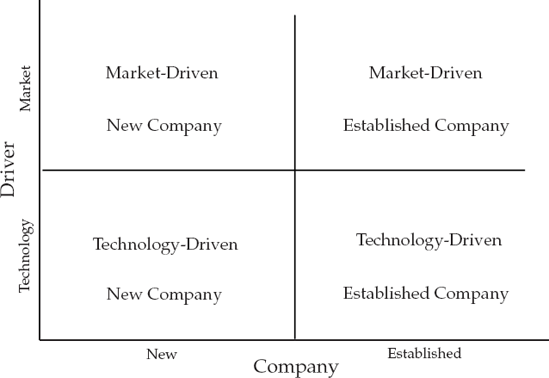

To illustrate the relevance of the Continuum model in everyday business, consider that most companies involved in developing a product and bringing it to market are either new or established companies, and their products are either technology- or market-driven (see Figure 9.1). The first category, the technology-driven startup, involves the entrepreneur-inventor who develops the next new thing and then forms a company to exploit the invention. In the second category, an established company with a marketing and sales division develops a new technology and brings it to market with a mature and experienced management team. In this example, the technology may have come from a merger or acquisition. Microsoft would fall into the third category of a market-driven established company, assuming that the R&D group was driven by data from consumer surveys and not solely from an engineer or programmer enamored of a particular technology. The fourth category of company type is the pure market-driven startup, such as a company started by recent MBA graduates, for example, who are aware of market demand for a product and set out to obtain the resources needed to bring their idea to reality. As described next, the odds of success and the challenges associated with each type of company are very different, and yet the decision makers are faced with many of the same issues.

Companies that are established primarily to exploit a particular technology have particular challenges along the way to profitability. Most technology-driven companies are small, two- or three-person operations that are characterized by limited resources, which are devoted to developing a viable prototype. The Apple computer and the VisiCalc electronic spreadsheet are two notable examples of the potential of this type of business venture.

These companies typically start at or near the Technical Gateway of the Continuum, with at least some form of prototype in hand, but with absolutely no knowledge of the potential marketability of the product beyond the developer's typically limited perspective. The challenge facing the decision makers is to take the technically viable concept driving the company and move it along the Continuum to become a successful product. The demographics of the typical user may be undefined, and the viability of the business plan unknown. Also, the soundness of the revenue model and profit potential, based on cost of production, marketing, and distribution, may be undefined, and the availability of resources required for production may not even have been considered. Clearly, the major stakeholders, if any, are the technical experts and their backers. Technology-driven companies that are formed on the basis of nonexistent or potential technology are commonly susceptible to intellectual property and licensing threats from the competition because the company many not have the resources or the energy to devote to protecting its intellectual property. Although there are exceptions, usually the company's decision makers are technocentric, and they usually have difficulty raising capital to address their nontechnologic weaknesses such as hiring employees to adjust the mix for market growth instead of hiring purely for R&D. In addition, if the company is ultimately successful in creating a working product, its success in the marketplace may be usurped by a company that offers a technically inferior product but has better marketing, service support, and customer reach.

Lacking the benefit of a marketing group early on, the product may not be suitable for the potential customers, and there is a greater likelihood that the product will need to be reworked after it is introduced into the marketplace. Products developed by this type of company tend to have the greatest likelihood of consumer recidivism and have a rate of consumer adoption that is slower than market-driven products. Because there is no brand recognition, customer expectations are unknown, and customers may undervalue the product, even if it is technologically superior to similar products on the market.

The major sticking points for the technology-driven new company are the Product Point and, to a much greater degree, the Market Gateway. Many developers never quite manage to create a viable prototype, despite their technical prowess. For example, when Alexander Graham Bell developed his Photophone—a telephone that used light as the communications medium—he was unable to create a demonstration unit that worked in typical weather conditions. Other than carefully controlled demonstrations during Bell's speaking engagements, the Photophone was not widely used.

In addition, the new, technology-driven company typically has major challenges in transforming its corporate culture and developing a marketing vision. There are corporate culture issues of focus, leadership, attracting and retaining quality employees, making payroll, and maintaining employee morale. Because money tends to be in short supply, stock options are commonly used in this type of business to attract and keep good employees—a tactic that works only as long as the potential for success seems significant. In the area of marketing, new companies that are technocentric by design typically face the challenges of assessing the competition, establishing corporate visibility, advertising, and adjusting their products to match shifts in the political economy.

The story of the lone inventor toiling away in her garage or huddled in her computer cubicle creating the next killer application, and bringing it to market is the stuff dreams are made of, but rarely what successful companies are built from. Bill Gates and Larry Ellison, programmers turned multibillion-dollar CEOs because of their entrepreneurial spirit and ability to convert their technical prowess into viable products, have certainly been role models for many other programmers who attempt to follow their footsteps.

However, the authors of this book have worked with companies started by intelligent, well-meaning innovators who poured years of effort into a technology that, although it worked, had mixed long-term viability in the marketplace. A few of these persistent innovators had the knack for marketing or the luck of finding a third party in need of their technology. However, usually the only ones who made money in these arrangements were the original founding team and a host of accountants and business attorneys.

The winners in this type of venture come to realize the value of the concepts embodied in the Continuum model. At some point, typically after they have spent a considerable amount of money developing a prototype or a fully deployed product, they realize that they underestimated the amount or capitol and expertise it takes to establish distribution channels, start a marketing campaign, or use a sales force most effectively. Of course, successful companies come to this realization early on and hire a seasoned CEO, head of marketing, sales, and other specialists needed to attract customers as well as a steady stream of investment capitol. Even these companies pay the price for viewing the development process as a binary one in which a technology focus is suddenly replaced with a marketing focus, instead of the progression defined by the integrated Continuum model.

Many more new, technology-driven companies fail because either they never appreciated the reason that customers did not initially purchase their product or they brought in marketing personnel too late. By the time they have an objective measure of market demand, their fate during initial market introduction has been determined. Although it seems obvious in this extreme case, many established companies act in the same myopic way, thinking that they can handle the customer demand side after a product has been introduced to the marketplace. Unfortunately, many potential inventions die this way, only to be rediscovered later. In this regard, the primary value of the Continuum model in a new, technology-driven company is in proper sales and market planning in conjunction with product development, regardless of whether the founding team has the funds to hire a seasoned CEO or retain a marketing firm.

However, if the organization's leaders work with the understanding of the marketing and customer behavior hurdles ahead, they may be able to direct their work so that, for example, modifications based on changes in customer preferences can be made more readily in the future. A software developer, for example, could make a relatively small investment during the programming stage to use an architecture that supports a variety of end-user interfaces. If customers do not like the initial interface, the company is in a good position to modify its product quickly. Conversely, coding an application with the mindset that the developers know what is best from a customer perspective could easily result in an application with an interface that is virtually impossible to rewrite affordably and quickly enough to respond to true customer preferences.

Of the technology-driven companies, those with the greatest likelihood of success have already established themselves as capable of surviving in the marketplace. That is, the founders either were aware or became aware of the natural progression of idea to viable product in previous ventures. Often, technologists who have access to talent in other areas as well as technical expertise are called upon to run established companies that use a technology-driven approach to product development. Alternately, the CEO of a technology-driven company can acquire the intellectual property rights to the technology, demonstrate customer demand in the marketplace, and then license the technology to a company interested in growing the market for the product.

Like the new company driven by technology, the established company typically begins with some form of prototype in hand and minimal market analysis. As such, the challenges facing the decision makers are similar to those facing the decision makers in a new company. However, assuming the new technology drive is not completely unlike existing products within the current product pipeline, the decision makers are more cognizant of the likely market demand, and they'll have an easier time of raising capital for the venture because of a successful track record or because the organization is large enough to obtain funding from existing budgets. An established company may already have an internal employee mix that is seasoned for growing a product, including marketing support that can be called upon to help support an initial sales effort.

However, as illustrated by many companies that spun off dotCom entities, success in one type of business does not confer automatic success in ancillary, unrelated ventures. Most of the dotComs established by Fortune 500 companies as potential revenue generators have been relegated to customer support and advertising portals and, in only a few instances, are they providing eCommerce an alternative source of revenue from traditional brick-and-mortar efforts capable of sustaining the online offering. In terms of customer behavior, the rate of adoption, likelihood of customer recidivism, and need to rework the product after introduction are virtually identical to those ascribed to new companies that are technology-driven. However, the customer expectations of an established company's technology product are highly influenced by the previous products released by the company.

Similarly, an established company pursuing the development of a product from a strictly technological perspective is likely to get stuck on the same issues that plague a new company, but to a lesser degree. Among them are marketing-related issues such as establishing an advertising budget, obtaining coverage by the trade press, establishing corporate visibility, and satisfying customer expectations. The issue of expectations should be addressed, at least in part, by the introduction of the company's previous products. However, this advantage is only to the degree that the CEO and other decision makers make use of their knowledge of the market early on in the Continuum.

The primary value of the Continuum model to decision makers is as a streamlined communications medium that keeps marketing, sales, and R&D in sync. Thus, once management decides to expand the effort beyond R&D, product development can move as swiftly as possible through the various phases of the Continuum in collaboration with other departments critical to the successful introduction of the product to the marketplace. For example, if sales and marketing know that the company is still a year away from a fully debugged product (Completion), the organization can plan its budget and resources for initial test marketing and product roll-out activities. Similarly, in communicating with potential investors, the Continuum model can help establish reasonable expectations on time to market, resource requirements, and overall financial risk assessment.

Now consider the market-driven established company, whether a Fortune 500 company or small biotech firm. The main difference between this model and the previous two models is that technology is secondary to market considerations. That is, the goal is to satisfy customer wants and needs by providing a product with specific benefits, as opposed to a goal of somehow finding a niche for a developed technology. Market-driven product design in these companies begins early on, at Inception, and involves the analysis of customer demographics, likely demand, analysis of the competition, and other long-range projections that relate to the viability of a new product development effort. Because of this focus, many projects never make it to Inception because a viable financial plan cannot be agreed upon, regardless of the technological implications.

Once the project is begun, the major challenge becomes one of creating a technology that will satisfy the needs of the targeted consumers—the converse of the situation in a typical technology-driven company that is headed by developers. As such, there is greater likelihood of reworking the technology and eliminating grand scale features during the development phase of the Product Lifecycle.

One of the greatest advantages that the decision makers in a market-driven company have is that they start with knowledge of the customer's explicit needs and the potential revenue model that a successful product can provide. Then they can establish when to walk away from a technical approach because of unanticipated costs of development or production, and when to keep investing in development. Although a technologist who perseveres despite daunting challenges may occasionally beat the odds and come up with something that is both technically and commercially viable, in most instances it does not pay to follow a pure technology investment with more money until an advanced customer research effort is initiated. An example of an established, market-driven company that is investing heavily in R&D because of the economic potential is Corning. The management at Corning is investing millions in more efficient fiber optics cables, not for the sake of creating a better fiber, but because of what it considers the vast potential economic gains for low-loss optical fiber in the next few years based upon projected customer demand.

Of the four models discussed here, a product created by an established, market-driven company has the greatest likelihood of success. First, it most likely has much deeper pockets than a startup organization. Secondly, assuming the previous products were well received by the public, customer expectations are likely to be enhanced by the company's name and existing brand. Even so, there are many challenges, even for the most established market-driven companies. For example, the major sticking points in the Continuum model are at the Product Point and Completion. That is, compared to a technology-driven company, the sticking points are shifted to later in the Continuum. In addition to the marketing challenges, such as how to allocate advertising dollars to best differentiate the product from the competition's, there are likely to be significant technical hurdles to overcome as well. Dealing with standards, selecting the best technology partners, and evolving platform standards, for example, creates a degree of uncertainty to the company's ability to deliver technically solid products on time and on budget. A disadvantage may be a reliance by senior management on market research data that is either incomplete or unavailable due to the infancy of a new product category with an ill-defined customer base. Examples such as the PC and VCR serve to remind us that initial market research indicating there would be little commercial viability for several of the most commonly used technology products can be misleading.

Finally, compared to the typical startup, the management of an established company is more likely to be familiar with the relative advantages of the various business models, such as limited liability corporations, C-corps, and S-corps in supporting product development, raising capital, and attracting and keeping good talent. For example, a common mistake made by decision makers forming a new corporation is that in defining the initial stock splits they do not put aside sufficient stock for hiring future employees and for providing them with incentives for staying on. Although stock splits can be initiated, doing so has dilution and tax consequences that may be detrimental to existing stockholders.

The fourth category of product development company, the market-driven startup, has many of the characteristics of an established market-driven company. The main differences are in the areas of customer expectations and business viability. Unless there is a renowned CEO at the helm, customer expectations are unknown because the new company's brand does not have a legacy to build upon. In addition, being a new company, the business plan, revenue model, profit potential, and availability of resources are usually less certain than those of an established company.

A market-driven startup company's common sticking points include market and technology issues and company issues. As in a technology-driven startup, there are issues of how to attract, train, and maintain quality employees; ensure an adequate flow of funding capital; and comply with legal requirements. On the upside, a truly focused market-driven startup may be more flexible in its ability to take advantage of short-term changes in consumer preferences simply because fewer internal divisions and product lines are competing for resources.

In each of the previous four scenarios, the value of the Continuum is in timing, managing risk, predicting resource requirements, assessing the competition, and communicating the state of development to stakeholders inside and outside of the organization. As a concrete example, consider the process involved with bringing a book like this to market with an established market-driven publisher.

Inception: The publisher first evaluates a proposal for the book in terms of market potential, likely return on investment, likely effect from competing books, and other market-relevant issues.

Concept Development: The author reworks the proposal to address the publisher's marketing concerns.

Technical Gateway: The author demonstrates his understanding of the task by creating a sample chapter and submitting it to the publisher for review. Assuming the work is in agreement with the publisher's initial feedback, a contract is negotiated between the publisher and the author. The contract specifies deliverables, timetables, and responsibilities.

Prototype Development: The author begins to write the book in earnest, working with his team of researchers, readers, and editors, checking in periodically to inform the managing editor of his progress. The developmental editor periodically verifies that the transformation of the author's thoughts into the printed word is occurring on schedule and is of adequate quality. As important milestones are reached, such as completion of core manuscript material, marketing and sales personnel are notified. They then start to create promotional materials in preparation for sales kickoff in the next publishing season.

Product Point: The first draft is delivered to the managing editor.

Clarification: Working with the managing editor, the author provides refinements in the manuscript to meet the needs of intended readers.

Market Gateway: Publication; the book appears on the shelves and is listed in the online bookstores.

Stabilization: Rewrites for clarification and omission are made, based on the market response, including reactions from professional reviewers. These edits appear in future editions of the book.

Completion: The book's contents are repurposed for magazines, Web sites, symposia, and other markets.

In other words, the publishing company lives and dies by its ability to forecast exactly when events should and will occur. The publishing company orchestrates the work of dozens of professionals—from editors and indexers to publicity agents—in acquiring buy-in from resellers, setting up speaking engagements, and arranging reviews of the book. The printer is told how many copies of the book to print, based on the marketing group's assessment of the marketplace, the economy, the author's reputation, and the timeliness of the topic. In addition, if the publisher learns that a competing firm has signed an author for a similar topic, then the publisher knows when to expect the book on the shelves and whether it will be feasible to speed the book through the publishing process to meet or beat the estimated publication date for the competing work.

In establishing a process that works with a variety of scenarios, the publisher has instituted a form of risk management. For example, what if the author dies or is otherwise unable to complete the manuscript? What if the market shifts, and there is no demand for the book? What if a competing book appears on the market just before the book is to be released? How will such competition affect the return on investment?

Although this discussion revolves around the type of book you are reading now, it also applies to developing an eBook, software for a computer game, or a movie. Developing each of these media may seem like magic to an outsider, but because the developers and executive managers involved have experience and understand the process of moving from uncertainty to realization, it works. In this regard, a book can be considered a technological development project, where the author's ideas are transformed through a process that results in a marketable product. On a macro process level, most of the magic is gone, but there is still a degree of uncertainty and a need to forecast and maximize the likelihood of success and make provisions for inevitable failures along the way. After all, it is hard to tell if a movie or book will be a success. For example, only about 3% of books are blockbusters; the rest often only break even. However, the 3% that do make the best-seller list make up for all of the loss leaders.

CEOs and other decision makers spend much of their time filtering the important data from the noise. There are countless theories and events that may have significant or no effect on their business, and they have to decide which to consider and which to ignore. What is relevant in a booming economy, for example, may be irrelevant when economic conditions are very different.

However, deciding what information is relevant is only part of the challenge facing business leaders today. Knowing what to make of information is often just as difficult. For example, it may be clear that adopting a new approach to developing products is the best thing to do from a business perspective, but acting on that knowledge is typically fraught with challenges. The decision maker may have to decide which functions to automate and how to prioritize implementation in simple, doable steps. Addressing the limited ability of employees and customers to absorb new technologies and process change is generally more challenging than the discrete technological issues involved. In addition, customer expectations regarding product features and benefits will likely continue to rise. In technological arenas, customers expect new products to improve their lives, perform better, and be easier and simpler to use.

As Wall Street searches for the next new thing and investors rethink their investment strategies, the Internet, World Wide Web, and wireless will proceed along the Continuum, just as TV, radio, and AC power did decades earlier. Whether biotech, nanotech, alternative power, or some other area becomes the next "can't lose," sure-fire investment, it will begin as a concept that an entrepreneur or research team brings to the Technical Gateway and then someone with entrepreneurial savvy shepherds to the Market Gateway.

It is up to the CEO and other decision makers to assess and respond to the changes the Web and other technologies made in their industries. For example, banks, which are really information-handling companies, are likely to be affected by even small changes in the effectiveness of data and voice communications technology. Other industries, such as large-ticket consumer electronics, in which the customer often wants to look at, touch, and determine the performance of a device before purchase, may not benefit much from an increased use of online communications.

Taking the global view, as many U.S. companies have been forced to do since the U.S. market stagnation and economic downturn of 2000, entering emerging markets for technology-based goods and services holds enormous potential. For example, in China, where only about 10% of employees have PCs on their desks, the potential for computer sales is significant. However, there is the issue of infrastructure; most provinces do not have any form of wired Internet access. As such, there is a vast potential market for wireless Web access once an open market can be achieved.

In addition, even though the Internet was supposed to be the great leveler, it has not been. To the contrary, those few with access to the technology have excelled in obtaining information more expeditiously, whereas those living in areas not serviced by adequate Internet infrastructures not only do not have access, but they do not have the education required to use and understand how to incorporate the rapidly evolving technology.

Regardless of the state of the economy, businesses operate in a competitive, resource-limited environment, with the reality of finite Product Lifespans, only partially predictable customer behavior, and the need to innovate with an R&D and marketing focus that shifts along with the different stages of product development. The patterns and relationships defined by the Continuum model provide businesses involved in new product development with a tool they can use to successfully lead their companies through the inevitably challenging times ahead.

The Continuum model is a tool to help steer executives past the potholes that are as common among new technology startups as they are among established blue chip companies. These potholes generally include the inability to understand how to equitably allocate precious financial and human resources to propagate a customer-driven marketing effort while allowing for the right mix of freedom and creativity within the R&D department. It is critical for the CEO to understand how each point along the Continuum demands that the senior management team allocate resources proactively rather than reactively in response to external political and financial change.

The concept of bringing an idea to the marketplace has a romantic quality. Many of us like to imagine the hard-working scientist entrepreneur in his garage working throughout the day and night perfecting the next great invention that will magically change our lives for the better. However, the hard reality is that magic is often the by-product of well-thought-out processes. Just as a magician will not go on stage without thoroughly studying and practicing her craft, a successful entrepreneur must not initiate a new product development or marketplace introduction without a plan for addressing the technical, financial, human-resource, and customer-related issues. In order to keep an organization focused throughout each stage of the product Continuum, the CEO must foster a transparent communication strategy between internal personnel and the external marketplace.

The challenge of removing the traditional friction experienced between technology staff and marketing managers is best accomplished though promoting early interactions between developers and sales staff immediately from the initial concept of a product idea. The average new product development effort traditionally can last anywhere from six months to several years with a development team varying in size between six to over 50 people depending on the complexity of the new technology and availability of investment capitol. Thus a typical work breakdown structure (WBS) or recipe for developing a new product and bringing it to market may comprise well over 450,000 individual tasks over the course of a year. The primary goals and objectives of the management team are to deliver a product offering on time and within budget that can sustain profitability once introduced into the marketplace. In the context of adhering to these goals, if the manager is not capable of establishing continuous communications, and maintaining project team accountability, the likelihood of a successful product development effort that meets the customer's expectations will be low.

Just as with a favorite family recipe that has been handed down generation-to-generation, knowing the ingredients will not ensure a successful cooking experience. Similarly in business, a well-thought-out product development plan, hiring strategy, financial model, and marketing plan are only part of the requirements to guide an organization along the Continuum. The senior management team and founders must provide the vision of knowing when to apply pressure as well as mitigate tensions during the sticking points along the Continuum. For example, it is not enough to tighten the fiscal screws on a sales force struggling to meet volume-driven quotas for a new technology product when the customer base has not been adequately defined. Similarly, it is not particularly productive to reduce the R&D budget when certain product features are discovered not to meet immediate customer needs. As with manufacturing and production systems, the concept of zero-defect management in transforming a new idea into a sellable product is more of a philosophy rather than a realistic or attainable goal. The important concept for the manager is not how to avoid sticking points along the Continuum but how best to negotiate undue delays in bringing a product to market and sustaining a successful revenue stream.

The initial introduction of a new product is often fraught with challenges for both marketing managers as well as the production engineers. A technology product rarely ever works exactly the way the customer wants it to. Establishing a customer relations management (CRM) system that allows for immediate feedback from the customer to the sales manager and on to the product engineer will create the ability to change product specifications that best meet current and future customer needs. A properly working CRM system will also allow for a focused approach in setting realistic short-and intermediate-term development and sales goals.

Just as all politics are local, so are product development efforts. Preliminary sales projections and market forecasts are mere speculation until a technology has obtained customer buy-in beyond the original test market scenarios. The earlier customer expectations and purchasing behavioral patterns are understood for a new product, the greater the likelihood that the development and sales efforts will meet the customer's needs. As discussed in earlier chapters, the demise of the dotCom industry in the 1990s, the Macintosh loss leadership to IBM in the 1980s, and the downturn in domestic car sales to foreign imports in the 1970s are all examples of how once successful organizations lost sight of customer needs and were overtaken by competitors in the marketplace.

A hard lesson learned is that a novel technology or product that is successful at one point along the Continuum does not necessarily get continued acceptance in the marketplace. By continually obtaining and translating end-user feedback into product enhancements, customer support and sales managers can help evolve a new product introduction into one that reaches successful market maturity. Results of this type of due diligence will be to establish brand loyalty and increase total market share.

Imagine after immediately crossing the finish line of the Boston Marathon—one of the most physically grueling challenges the human body can voluntarily seek to endure—the racing committee officials say you must immediately restart the race in order to qualify to compete for next year's race. Yet each time you somehow manage to cross the finish line you are repeatedly told in order to continue to qualify you must repeat the most mentally and physically challenging endurance test that you have ever experienced to date. Aside from the physical pounding and psychological strain of each successive race, the challenge is getting mentally focused and properly motivated to start all over again.

This simple analogy is a reasonable comparison to the continuous, extremely high-level commitment it takes to initially launch a product and sustain profitability and market share growth along the Continuum. Changing customer preferences, emerging competition, turnover in senior management, and an ever-shifting external political landscape all contribute to the need for a CEO to pay unrelenting attention to shifting priorities and resource management across the Continuum.