4 Personify Your Consumer

The next step in crafting an effective design strategy is developing a deep understanding of potential customers, what they seek in the category, and their needs, desires, and aspirations. Creating meaningful consumer experiences depends on these insights. Developing and mapping personas can enable companies to identify target consumers and set design priorities.

Redesigning an Icon

Leading audio products company JBL (James B. Lansing) Professional had a problem. After more than a decade as the leader in the portable powered speaker market it created with the original EON line of portable public address (PA) speakers, JBL’s competition had begun encroaching on the EON’s market share. In the years since its introduction in 1995, the EON had become a global product and sold nearly one million units…drawing more than 300 competitors into the category in the process. Though there was no single competitive threat, there were many “me too” products nipping at JBL’s heels. The category was becoming commoditized. JBL knew it needed to take preemptive measures to retain market leadership. What it needed was a new generation of EON that raised the bar in all categories.

JBL set about creating just such a product. When its engineers felt they’d perfected the advanced technology required to offer a higher performance product at a substantially lower weight, it was natural to enlist an industrial design firm to create the new generation of EON…after all, the original EON was a product conceived in an industrial design (ID) firm.

Simon Jones, director of marketing for JBL Professional, summed up the challenge succinctly, “The bits that we do best are components and engineering. We make our own components— woofers, compression drives, tweeters, etc. and we can control those—and those are our competitive advantage. These are the bits you don’t want to blow up. But we stick all of those things in a box. You don’t see them at all. You can hear them but you don’t see them. That was the challenge for us with design…to bring that same level of quality to the outside …”1

JBL’s internal research showed that consumers relied heavily on visual cues to judge the quality of the speakers, even after every other factor was controlled. Retailers and company executives were aware that the speakers had to look good to sell, but the extent of the relationship between the visual appearance and audio judgments (even from professionals) was surprising. Producing and surpassing the sound quality that people had come to expect from JBL required significant investment in research and new technology. To command the required price at retail, the speakers and other products had to communicate the value of the superior technology inside with a clear and compelling design language.

JBL engaged our design team to analyze the market, consumers, and opportunities, and to then provide analyses and recommendations as to how best to use design to communicate the value of the new lower-weight technology to showcase the well-recognized JBL brand DNA and most of all, to connect with buyers. The starting point for creating such a strategy was developing a deep understanding of the consumer.

Personas—The Mask of the Consumer

In Latin, the term persona refers to an actor’s mask…a tool once used to help an actor assume a character. In marketing and industrial design, a persona still represents a fictional character—but rather than used for assuming a role in a play, individual personas are created to represent user types and market segments.

The persona method has its roots in the software industry in which Alan Cooper2 is widely credited with laying the foundations for using personas to guide the design process. Cooper came upon the use of personas naturally—intuitively imagining a single target user in his own software development process. Much like an actor in a play, Cooper would quite literally play act how users would accomplish their job as he created a user interface. It wasn’t until Cooper moved from software designing to consulting that he suddenly realized the need and value of using personas to achieve clarity and understanding among development team members.

Personas aren’t just dreamed up. They’re constructed as the result of careful research. An individual persona is a fictional representation of real users. Though personas aren’t real, it is vital that they feel real to all stakeholders. A basic persona can include a name, photo, age, income, and family status. It describes and illustrates their likes and dislikes; what’s important to them; and their behavior traits, perspectives, skills, and goals. Most important, each persona includes specific insight into what they seek in the market category at hand and how they relate to a specific experience or product. Ultimately, a persona embodies the needs, desires, and aspirations of the users it represents.

Personas Fuel Intelligent, User-Centric Design

Today, personas are a valuable tool for guiding strategy, design, and innovation regardless of the industry. Personas transform data into the context of consumer experience. When used appropriately, personas help stakeholders make sense of volumes of data, empathize with consumers, and mitigate risks by clarifying goals.

• Bringing data to life—The motivations and thought processes of consumers are critical inputs that can determine the success of new concepts. But all too often these insights get buried in data. The sheer volume of data contributes to the confusion, but even more problematic is the lack of depth and meaningful context to the numbers. As a result, products and services tend to get compared to the competition based on features and price points. But what consumers want to know is how the product or service fits into their lives. This is also exactly what design teams need to know. Personas bring this invaluable context to life so that the needs, desires, and aspirations of target consumers can inform the development process.

• Engaging the power of empathy—Personas help teams develop an affinity for the people they are designing for. They find parallels with friends, family, and associates and draw inspiration from their traits. Empathizing with the needs and aspirations of individuals creates focus, understanding, and excitement for all stakeholders in the design process. We all know what we would never buy and why; personas help a team develop this understanding for a variety of users. Personas don’t just put a face on an otherwise abstract user—although that is valuable. Indeed, much like the actor’s mask, deftly drawn personas allow designers to see the world and the design through the eyes of a specific type of user. This vision suddenly makes it clear what matters…what needs are prioritized for this user, what visual and tactile cues will attract them, what features have relevance, and which are superfluous.

Many of the greatest stories of innovation are actually stories of empathy. The idea for creating OXO Good Grips kitchen tools originated as Sam Farber watched his wife struggle to use a vegetable peeler with arthritic hands. The ability to see a developing design from another perspective makes them an important tool for all stakeholders.

• Mitigating risk through clarity—When data is brought to life in the context of personas, it’s suddenly easier to find disconnects with the data or with company aims. Inauthentic personas—ones that are drawn from real data but don’t resonate in real life—are easily spotted. Personas that are not immediately recognizable to brand executives can open up a dialog and lead to new insights.

Clearly defined personas also help teams avoid the pitfalls of either designing according to their own preferences or constructing an idea of the end user to fit the design, rather than designing for clearly targeted end users. The value of innovation is directly proportionate to the degree to which it connects with consumers. Steelcase CEO James Hackett famously challenges his managers presenting new ideas with the question, “What’s the user insight that led to this product?”3 The development of personas forces teams to demonstrate that they have digested and understood the data, which then enables them to set and agree to design priorities. This can prevent design failures such as creating a complicated kitchen gadget for a segment of users who have little time to devote to cooking.

The magic of presenting carefully drawn personas to an interdisciplinary team comes in the murmurs of instant recognition, “Hey, I know that guy!” This recognition can often bring valuable refinement as team members add insights that can be synthesized into the personas. Everyone has a clear idea of who a persona is and isn’t. “Bob wouldn’t do that.” Or “That would appeal to Terri, but Jill would hate it.” This clear consensus inspires teams and helps stakeholders stay on track through long and complex development cycles. Teams focused on designing for the target users bring the most return on investment. Personas deliver this focus.

What Goes into a Persona

Although the depth of personas can be scaled on a project-by-project basis, the richer the persona, the more value it brings to the design process. The most common data sources for developing personas are ethnography, demographics, market research, and consumer analytics (see Figure 4.1).

• Demographics—Companies have an obvious need to know the general size of the target populations and purchasing power of their consumers through the use of demographic information. Demographics are especially helpful in ensuring segments are not overlooked and that segment sizes are considered when projecting potential return on investment (ROI).

• Market research—In established categories, consumer feedback about products and services can be useful, especially for identifying remaining pain points or suggestions for improvement. This research can be conducted through surveys, interviews, or by “listening in” as consumers talk online about their experiences in reviews, blog posts, forums, and tweets.

• Consumer analytics—Companies such as Amazon and Netflix have demonstrated the value of sophisticated consumer analytics. You know, those “if you like A, you might also like B” suggestions? That’s consumer analytics in action. Costco chief Jim Sinegal, for example, knows that toilet paper and bananas are items that appear in many shoppers’ baskets, so he priori-tizes keeping their prices low.4

© RKS Design

Figure 4.1 Inputs for persona development

• Ethnography—Ethnography is simply a detailed observation of human behavior. It is an elevated form of people-watching that includes notes on times spent on various stages of an activity and consumer reactions to their environment. Companies also use tools such as eyeball tracking and mystery shoppers to capture data that might otherwise be lost (for example, perhaps a consumer ultimately purchased Special K but spent 5 minutes looking at Cocoa Puffs). Shadowing consumers through the purchase process provided invaluable insight in the Amana case in Chapter 2, “Enable Your Stakeholders.”

What You Get Out of Personas

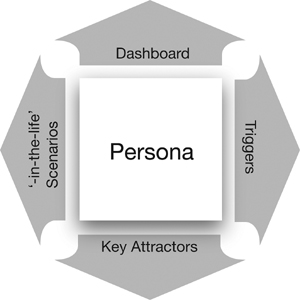

Although the depth and scope of persona development can be scaled dependent upon timelines and scope, fully developed personas incorporate Persona Dashboards, Day (or Week)-in-the-Life scenarios, Triggers, and Key Attractors (see Figure 4.2).

© RKS Design

Figure 4.2 Outputs from persona development

• Persona Dashboard—A persona dashboard gives a comprehensive snapshot of the user types in question. Beyond a name and photo, the dashboard includes key demographic information (for example, age, gender, income, family, location, and so on) and a narrative about who they are and, in particular, how they approach products and designs in the category under consideration. Often, dashboards also include information that gives insight to the personas’ taste—what they wear, how they spend free time, what other products they buy, and what brands they use.

• Triggers—Triggers are the intangible things a product delivers. For example, some want control above all else. Others need ease-of-use. Still others are driven by desires to nurture others. Triggers run a spectrum from strictly rational to completely emotional. Identifying and prioritizing which triggers are most important to specific personas is an essential step in understanding how users will relate to market offerings.

• “-in-the-Life” scenarios—Day- and Week-in-the-Life scenarios dive deeper into a typical day or week of the personas. What activities fill their days? What challenges arise? Understanding the constraints and usage scenarios that are likely to take place creates an intimacy with the consumers and helps identify pleasure and pain points (aspects of a process that are either fun or the source of challenges and discomfort) in the consumer experience. These can effectively inform the design process, guiding teams to better understand which solutions will connect best with consumers.

• Key Attractors—Although triggers are intangibles, key attractors are much more concrete. These are the specific design features that engage a particular target group of consumers. For example, a new mother may be attracted to baby products whose features can be operated with one hand. These Key Attractors can also be evaluated against existing market offerings (see Figure 4.3).

Persona development generates insights that would have otherwise been forever trapped within piles of consumer research. Constructing fully developed personas is a time-consuming yet invaluable process. Empowering design teams to see the marketplace through personas enables them to understand and draw inspiration from consumer experience.

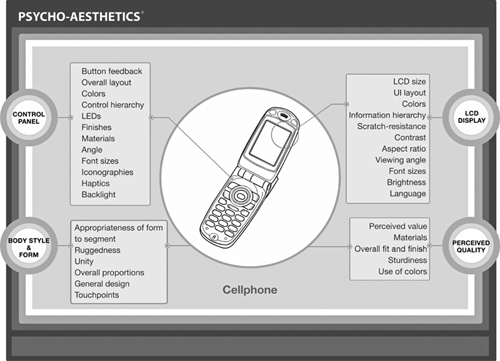

© RKS Design

Figure 4.3 Key attractors for cell phone concepts

Using Personas to Guide Design

When JBL approached us to redesign its iconic line of EON speakers, we quickly realized that the purchasers of powered portable speakers encompassed an incredibly diverse array of individuals and institutions. The team began by speaking with musicians, rental houses, retailers, and all other kinds of users, from churches to corporate settings. We also worked directly with several dozen department managers of Guitar Center, all of whom were musicians and users of the product, to gain further insight and feedback on our design directions.

The single most critical finding was that people use EONs to make their living. The speaker was a professional tool for many, and the addressable market was expanding to include “prosumers.” The people who fell into this category included those who pursued music/DJ activities on the side and needed a reliable and powerful system. Next, the team studied consumer reviews to learn what features consumers loved and hated about existing products. Detailed Persona Dashboards and Day-in-the-Life scenarios were created to develop a better understanding of how the wide variety of EON consumers interacted with their speakers.

The usage scenarios that were described during interviews were acted out by members of the design team using a wide range of products in the category. In the course of our research, we heard from musicians who piled all their gear in a van or pickup in the morning, drove four hours, set up, performed two shows, and then had to break down and reload their equipment for their late night return home. For rental houses, having equipment available that looked powerful and remained in good condition over time was important. As more people came into the market, it was important that the setup become as painless as possible. The benefit of the lighter-weight technology soon became apparent as the team struggled with offerings that were bulky, heavy, and difficult to mount.

A narrative was also developed for each major category of consumers. Although everyone spoke about the need for great sound, this was not a revelation. It was also the area in which JBL engineers had the greatest credibility. The importance of styling was also becoming an issue as more competitors entered the market. Retailers had expressed a desire for a high-quality “look” but were vague about what that entailed. The speaker had to communicate power and durability but also draw attention to the new lightweight technology. These disparate goals required a design that could capture a wide range of needs—image, reliability, and better user experience.

Mapping Personas

After personas have been developed, they can be mapped just like products were mapped in Chapter 3, “Map the Future.” Although it may at first feel odd to put people on an X–Y grid, when you realize placement is framed by the consumer experience and based on a specific product or service category, such placement becomes clear. As with products, persona placement is based on the Consumer’s Hierarchy of Needs, Desires, and Aspirations (vertical axis), as shown in Figure 3.3, and the relative interactivity of the experience (horizontal axis). You might expect, for example, to find a highly technical engineer persona placed somewhere in the lower-right Versatile quadrant, as shown in Figure 3.4. On the other hand, someone who is focused on high aesthetics and a simple user experience would be placed in the Artistic quadrant in the upper-left quadrant of the map.

It is important to remember that the same individual can take on different personas according to the category. For example, a woman may have emotional needs in the Artistic quadrant when looking for a handbag (for example, looking for something aesthetically distinctive) but may be in the Versatile quadrant when shopping for a car (for example, the primary focus may be on safety, reliability, and price). A successful bachelor may be an Enriched persona when looking for cars or clothes and a Basic consumer for kitchen implements. Although some of the personas may seem familiar, they should be reevaluated as new products are developed. Their lives evolve quickly, and a reality check often yields insights that can change the course of a design. It also gives the teams a chance to go into the design process with the current understanding of the consumer’s life.

During the development process, personas are refreshed on a continual basis. The placement of personas on the map depends on how well the category is established. For existing offerings, preferences and pain points are known. In new categories, placements are qualitative judgments inferred by other choices in their lives such as cars, books, and music. This is a process that relies on the professional assessment and experience of designers and a careful selection of target consumers.

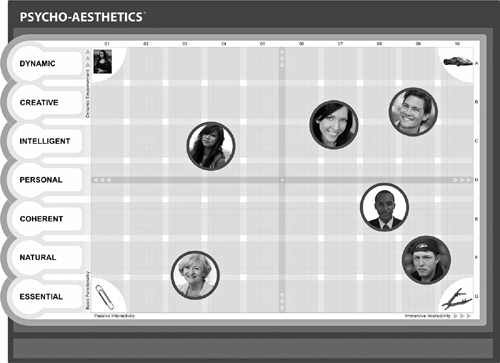

To go back to our example of the cell phone segment (see Figure4.4), a persona map shows the needs of various individuals represented by a persona. These placements apply only to this category.

© RKS Design

Figure 4.4 Mapping of personas for the cell phone segment

In the Basic quadrant (lower left), Mary wants an easy-to-use cell phone to make calls when she is out with friends. She prefers to make longer calls from her home and does not talk on the cell phone while she’s driving. It is important to her to know that she can reach her family in case of an emergency.

In the Artistic quadrant (upper left) is Kylie. She loves fashion and trends as a way to express herself. She uses the phone mainly for talking to friends and texting and wants something that looks unique and fits in with her style.

In the Versatile quadrant (lower right), Trent and Joseph have different professions but travel for their work and need to keep in touch with a wide network of people, review documents, call in to meetings, and manage their schedules. They need a reliable cell phone and service. They are interested in multiple functions and speed when they look for a device.

In the Enriched quadrant (upper right), Sabrina and Tim are looking for function as well as some fun and style. They have moderate phone use but use their computers for games, music, and connecting with friends. These activities take up a lot of their spare time. They would be interested in a phone that combines beauty with functions that can be used for both work and entertainment.

In the case of JBL, it was clear that, though the target personas demanded great sound, they also needed great portability—a desire few of them could articulate at the time. As we looked at interactions in the marketplace and in retail settings, we understood how consumers tested speaker weights. They knew they’d be lugging these things around for years to come. Reading a weight on a box meant little. Lifting a speaker and feeling the weight was what gave users a real sense of the product.

Persona analysis also made it clear that, despite the breakthrough technology JBL packed into the new EON, great sound was a base-line—a minimum requirement. The best opportunities for improving the consumer experience lay in enhancing portability. After developing a list of Key Attractors, we set about delivering JBL’s high-performance technology in a design that was more functional and portable than ever before.

Getting a Handle on the Right Design

Even with stakeholders aligned on these goals, creating a design that addressed the needs of targeted users was a complex challenge. In a church or school, for example, the appearance of the speakers became part of the overall architecture because it was often elevated during events. For bands and DJs, the look of the speaker had to reinforce the music and image of the musicians. For all settings, the speakers needed to convey a sense of power and quality.

To do this, a distinctive “face” for the speaker was created. It included bold port vents to provide a visual accent and evoke fond memories of the original EON. A squat “bulldog” appearance was developed to indicate the ruggedness and workhorse performance. A perforated metal grille was added to protect the components and reinforce the impression of quality. These features needed to be balanced with the real-world usage scenarios that had been observed. To minimize abuse to the speaker and users alike, the design team removed all hard edges and corners. This made the EON durable and comfortable to move around. There are no corners to bash into knees and legs or to catch and gouge as they’re slid in and out of cars. The new shape also helped to prevent the speakers getting banged up when corners get bumped in transit. Testing validated that the aesthetics were successful with consumers. The new design made people feel good about themselves by giving them confidence in the sound and appearance of their equipment. The uncluttered appearance also fit well in a variety of settings.

By understanding the challenges of consumers and rental companies transporting and stocking the equipment, all stakeholders understood that making it lighter was a huge benefit that could be leveraged. However, it was an attribute that consumers had to discover through interaction, because musicians and others in the category were primed to seek out the best sound quality. Thus, we included in our strategy a directive to create a design with a handle that begged consumers to pick it up. We knew that once they did, they would fall in love with JBL’s new lighter-weight technology.

With this in mind, we gave the handles particular attention. This is where the speaker integrates with the user. First, our designers had to determine handle size, number, and placement—both to balance the weight and in consideration of how users would actually maneuver and carry this speaker. The EON features an on-board mini-mixer and puts out a massive 450 watts of power, yet weighs only 33 lbs—a full third less weight than competitors. To take full advantage the new lightweight technology, the flagship EON features three full-bar handles. Each handle, one on the top and one on each side, is placed for optimal ergonomics and balance and over-molded with a soft comfort-grip.

The top handle was also key to the retail experience (see Figure4.5). After going to market, we observed the same response time and time again. The design invited people to pick up the speaker. They saw the EON sitting on the floor with the top handle calling out to them from a perfect mid-thigh height. After picking it up, consumers often did the same with competing products. Everything else suddenly felt heavy by comparison and by design. Inevitably, the consumer would return to the EON and smile. “Yeah, it really is that light.”

© RKS Design

Figure 4.5 JBL EON 515 speakers

The result of persona insight was a new EON that connected with consumers who knew that speakers need to “perform” even after the final song. And the EONs do exactly that. As one band leader for Judge Jackson praised, “Light as a feather. Good to use after a gig like that ‘cause they’re so friggin’ light and accessible. That’s what we want after exhausting ourselves on stage for the last three hours.”5 Users felt “heard” and understood. This was a speaker designed to fit their lives.

A Fresh Perspective

Adding a handle at the top of the speaker seems like an obvious choice today, but at the time it was not. Incorporating this feature required rebalancing internal components and was a topic of much debate with the executive and design teams. Because creating a superior design was a major part of this effort, a simple add-on wouldn’t do. The proposed handle required a significant investment in molds and engineering to fit seamlessly with the design that had been created.

Well-executed innovations always seem obvious. The force of habit is so powerful that both companies and consumers often adjust to difficult situations rather than correcting them. Consider that despite the size of the home-improvement industry in the United States, it was only in 2002 that Dutch Boy created its Twist and Pour paint can.6 Until then, the consumer had an ever-increasing selection of colors, finishes, and even benefits such as environmentally friendly options. Yet the basic experience of opening the paint can, pouring it into a tray, and closing it was frustrating and messy—even for professionals. The “simple” solution had eluded many large and innovative organizations. The Twist and Pour can is made of plastic rather than metal, making it much lighter. It’s easier for the retailer to mix the color and for the consumer to use because the lid comes off and can be closed tightly—keeping paint fresh longer. The spout prevents spilling, and the shape of the container means that retailers can stack 14 Twist and Pour containers where only 13 traditional paint cans would normally fit. It was a win for consumers, companies, and retailers. Despite the benefits, the old scenario remains the norm.

Similarly, in JBL’s case, the answers that came about from investing in understanding the context of the consumer are quite different than the answers that would likely have emerged from the question, “How do I make a better speaker?” The latter would have perpetuated the focus on engineering that was already well recognized. The handles provided an opportunity to showcase engineering prowess that was visible to the consumer. Here, there was a happier ending—the EON was and continues to be a huge commercial success and a category leader. The right touch points can touch the heart—and can drive financial results.

Aside from a collaborative process and talented team, another key success factor was having some decision makers who “personify the consumers” within their ranks. JBL’s Simon Jones was not only an audio engineer but also a musician. He understood and empathized with the target consumer on a level that would be difficult for an outsider, enabling him to make decisions based on firsthand experience. This intimate understanding also allows both sides to trust in the process and make better decisions because the immersion from both parties is genuine, not theoretical.

It’s no surprise that the sectors that historically developed the most detailed use of personas and behavior were the ones that had to take on an incredible amount of risk: insurance, security agencies, and the military. Today, companies put their reputations on the line when they bring new products to market. Though information is gathered through observation and voluntary exchanges, here too personas are a powerful tool in mitigating risk. They also play an important role in uniting teams and developing strategies that result in positive emotional connections. The clarity and insight delivered through the use of personas creates a more efficient, effective development process.